NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Beach MC, Cooper LA, Robinson KA, et al. Strategies for Improving Minority Healthcare Quality. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2004 Jan. (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 90.)

This publication is provided for historical reference only and the information may be out of date.

The National Quality Forum (NQF) requested an evidence report on strategies for improving minority healthcare quality. In September 2002, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) awarded a contract to the Johns Hopkins University Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) to prepare an evidence report on this topic. We established a team and work plan to develop a report that would identify and synthesize the best available evidence on strategies shown to improve minority healthcare quality. The project consisted of recruiting technical experts, formulating and refining the specific questions, performing a comprehensive literature search, reviewing the content and quality of the literature, constructing the evidence tables, synthesizing the evidence, and submitting the report for peer review.

Recruitment of Technical Experts and Peer Reviewers

We recruited technical experts to provide input during the project, four of whom were experts from the Johns Hopkins University and had expertise in public health, quality improvement, physician-patient communication, and nursing. We recruited five external technical experts who had a special interest in improving minority healthcare quality and represented different perspectives including academic medical centers, professional societies and foundations (see Appendix D). We requested specific feedback from the partner (NQF) and from the internal and external technical experts for key decisions, such as selection and refinement of the questions.

We also sought comprehensive feedback on the draft evidence report from the partner, technical experts, and other peer reviewers. Similar to the technical experts, the other peer reviewers were recruited from a variety of organizations and included those based in universities, professional societies and foundations. Experts and peer reviewers were identified by team members in consultation with internal experts and AHRQ. (See Appendix D for a list of experts and peer reviewers.)

Questions

The original questions were refined through team discussions, input from internal experts, and review and feedback from the external technical experts. Listed below are the questions addressed in this report.

- What strategies targeted at healthcare providers or organizations have been shown to improve minority healthcare quality?

- Which of these strategies have been shown to be effective in reducing disparities in health or in healthcare between minority and white populations?

- What are the costs of these strategies?

- What strategies have been shown to improve the cultural competence of healthcare providers or organizations?

- What are the costs of these strategies?

Components of these questions were further defined for use in our review. Minority was defined as all non-Caucasian or non-white racial and ethnic categories, including, but not limited to, African American, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian/Pacific Islander. All clinicians were considered healthcare providers. This category included dentists, dental assistants, nurses, nurse assistants, physicians, physician assistants, pharmacists, mental health workers, community healthcare workers, social workers, and others such as alternative healers. For the purposes of this review, our research questions were meant to include any health professional or healthcare organization that provides health services to patients.

Analytic Framework

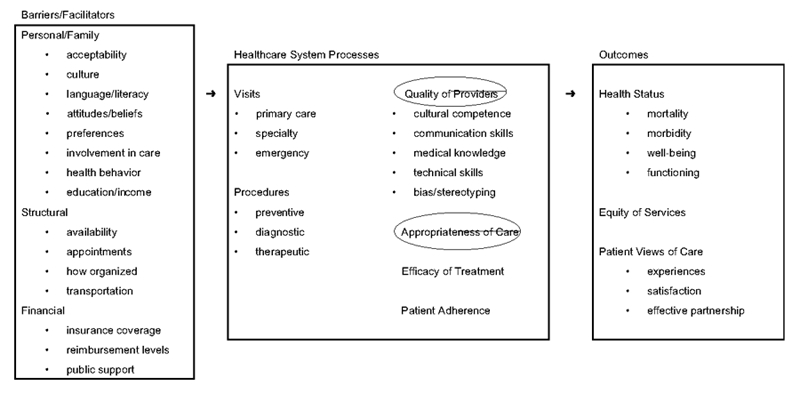

We used a conceptual model developed by Cooper and colleagues to create an analytic framework for our research questions.8 Below, we describe in detail the elements of the model (Figure 1) and its use in the report.

In 1993, the Institute of Medicine's (IOM) Committee on Monitoring Access to Personal Health Services set out to resolve many conceptual problems in the definitions of equitable access to health care. The Committee developed a model that provided a useful starting point for the conceptual framework that is used in this report.2 Indicators in this model are grouped according to barriers (personal, structural, and financial) that cause underuse of services and mediators (such as appropriateness or efficacy of treatment received, quality of provider skills, or patient adherence) that affect health outcomes and equity of services.

Cooper and colleagues modified the Institute of Medicine's access model to provide more specific directions for designing and implementing effective interventions to eliminate healthcare disparities.8 They expanded the scope of personal and structural barriers, specified utilization measures to include the type of setting, provider, and procedure, incorporated provider communication skills and cultural competence as measures of the quality of providers (a mediator in the original IOM model), and included patient views of care or patient-centeredness (a component of healthcare quality from Crossing the Quality Chasm) as important outcome measures.9

Specifically, they included additional personal barriers/facilitators documented in recent research on disparities to differentiate between the quality of healthcare received by patient race/ethnicity or to determine differences on the use of health services or in health outcomes for whites and ethnic minorities. These variables include family structure, patient preferences and expectations of treatment, patient involvement in medical decision-making, personal health behaviors, beliefs about health and disease, and health literacy.2

Cooper and colleagues also included structural barriers/facilitators within the system in their refined version of the IOM model. For example, in addition to the availability of care, how care is organized, and transportation, they included level of difficulty in getting any appointments at all with primary care physicians and specialists and the timeliness of appointments.10 A rationale for including these structural barriers or facilitators to health service utilization is provided by recent work showing that minority patients seen in primary care settings report more difficulty getting an appointment and waiting longer during appointments, even after adjustment for sociodemographic and health status characteristics.11

The IOM's access model included a category for mediators. A mediator is a variable (intermediate, contingent, intervening, causal) that occurs in a causal pathway from an independent to a dependent variable. It causes variation in the dependent variable (outcomes), and it is also caused to vary by the independent variable (barriers and facilitators). Health service use and quality of care variables are mediators between barriers/facilitators and health outcomes. Because studies of healthcare disparities document that ethnic minority patients are often cared for by physicians with poorer indicators of technical quality (such as lower procedure volume rates and higher risk-adjusted mortality rates) and that interpersonal care, including patientprovider communication, differs by patient ethnicity and by ethnic concordance in the patientprovider relationship,12 Cooper and colleagues expanded the quality of providers (a mediator between barriers and outcomes of care) to include technical skills,interpersonal/communication skills, medical knowledge, and cultural and linguistic competence.

Appropriateness of care, one of the categories of mediators, was conceptualized as the degree to which the care delivered to patients is consistent with current standards of care (for example, beta-blocker use for acute myocardial infarction, or guideline-concordant care for major depression). Efficacy of treatment, in contrast, was conceptualized as the degree to which a specific intervention, procedure, regimen, service, or treatment produces beneficial results under ideal circumstances.13 For example, patient knowledge about injury prevention might be considered a measure of the efficacy of a provider intervention targeting patient education and counseling skills regarding injury prevention. Patient adherence to recommended treatment (e.g., medication refills, health behavior modification, appointment-keeping) is another healthcare process measure. We included all mediators from Cooper's model in a broad category of healthcare system processes. Finally, in addition to health status and equity of services, Cooper and colleagues included patient views about healthcare, including their attitudes toward and experiences with care and satisfaction, since these have emerged as important outcomes that may differ by race, ethnicity, social class, and language.14

Interventions to improve quality of care and to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare might address a number of personal, structural, or financial barriers/facilitators and healthcare system processes from our conceptual model. Ideally, the intervention should target factors known to contribute to disparities in healthcare quality. For example, an intervention to eliminate racial disparities in cardiovascular procedure use might focus on patient preferences, patient-provider communication, and provider knowledge of treatment guidelines. An intervention to eliminate racial disparities in mental health care might target patient attitudes, such as stigma or fear of medications, primary care provider skills in recognition of mental health problems, or structural barriers such as the availability of case managers to improve coordination of care between primary care and mental health treatment settings.

Our conceptualization of cultural competence deserves further attention, since Question 2 in this report specifically addresses the state of the evidence regarding interventions targeting cultural and linguistic competence. No single definition of cultural competence is universally accepted. However, several definitions currently in use share the requirement that healthcare professionals adjust and recognize their own culture in order to understand the culture of the patient.15 Lack of cultural and linguistic competence can be conceptualized in terms of organizational, structural, and clinical (interpersonal) barriers to care.5 The Office of Minority Health defines cultural competence as the ability of healthcare providers and healthcare organizations to understand and respond effectively to the cultural and linguistic needs of patients.16 At the patient-provider level, cultural competence may be defined as the ability of individuals to establish effective interpersonal and working relationships that overcome cultural differences.12 The Liaison Committee on Medical Education includes the need for medical students to recognize and address personal biases in their interactions with patients among their objectives for cultural competence training.17 Medical educators have defined eight content areas (general cultural concepts, racism and stereotyping, physician-patient relationships, language, specific cultural content, access issues, socioeconomic status, and gender roles and sexuality) that are taught within a commonly accepted rubric of cross-cultural education curricula.18 We conceptualized cultural competence interventions as those targeting the relevant provider knowledge, attitudes, and skills (healthcare system mediators in our conceptual model).

In addressing our research questions, we acknowledge the potential for a conceptual overlap in interventions targeting quality of care broadly and those targeting cultural competence specifically. There may also be an overlap in interventions that are targeting an organization broadly and those that are targeting providers specifically. One example of this overlap would be an intervention that incorporates interpreter services. While one might consider interpreter services to be an organizational quality improvement strategy that targets structural barriers to care, this type of intervention also affects healthcare system mediators at the provider level, including patient-provider communication and provider cultural competence.

Figure 1 shows the elements of the model addressed by the studies included in the systematic review. We circled the major categories of healthcare system processes that were targeted by the interventions included in the articles that were eligible for our systematic review.

Literature Search Methods

The process of searching the literature included identifying reference sources, formulating a search strategy for each source, and executing and documenting each search.

Sources

Our search plan included electronic and hand searching. Several electronic databases were searched. In February 2003, we searched MEDLINE®, the Cochrane CENTRAL Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 1, 2003), EMBASE, and the following three specialty databases: the specialized register of Effective Practice and Organization of Care Cochrane Review Group (EPOC) which contains studies that report objective measures of professional performance, patient outcomes or resource utilization identified through extensive electronic and hand searching; the Research and Development Resource Base in Continuing Medical Education (RDRB/CME) a Web accessed database of materials concerning program evaluation, physician performance, change, and healthcare outcomes identified through electronic and hand searching; and the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL®).

Hand searching for possibly relevant citations took several forms. First, priority journals were identified through an analysis of the frequency of citations per journal in the database of search results as well as through discussions among the EPC team. We identified 12 journals to be hand searched (Appendix A). To ensure identification of recent publications, we scanned the table of contents of each of the 12 journals for relevant citations from January or February 2003 to June 15, 2003 based on the coverage of these journals in MEDLINE®. On the basis of its coverage, the journal Ethnicity and Disease was searched from the fall 2002 issue forward.

For the second form of hand searching, we scanned the reference lists of key reviews and reference articles. We used ProCite, a reference management software, to create a database of reference material identified through an electronic search for relevant guidelines and reviews, through discussions with experts, and through the article review process. The principal investigator reviewed a list of the titles and abstracts from this database to identify key reviews. We then examined the reference lists from these key reviews to identify any additional articles for consideration.

Finally, we examined the reference lists of eligible articles to identify any potentially relevant articles. This was completed by the second reviewer as part of the article review process (see description of article review process below).

Search Terms and Strategies

Search strategies, specific to each database, were designed to maximize sensitivity. Initially, we developed a core strategy for MEDLINE®, accessed via PubMed, based on an analysis of the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and text words of key articles identified a priori. Because of the exclusion criterion related to study design, the component of the strategy specific to Question 1 was combined with the first phase of a previously validated strategy for the identification of controlled trials 19. No limits were based on type of healthcare provider or specific minority group. The PubMed strategy was the basis for the strategies developed for the other electronic databases (Appendix A).

Organization and Tracking of Literature Search

Whenever possible, the results of the searches were downloaded and imported into ProCite. We used the duplication check in ProCite to include in the Minority Health Citations Database only articles that were not previously retrieved. This database was used to store citations and to track the search results and sources. We also used this database to track the results of the abstract review process and the retrieval of full-text copies of articles.

Abstract Review

Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied at each of the three levels of review. Criteria became more stringent as the process moved from searching, to reviewing abstracts, to reviewing full-text articles. After identifying a citation, two team members independently reviewed the title and abstract, and articles were included or excluded from the article review according to the criteria described below.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

During the abstract review process, emphasis was placed on identifying all articles that might have original data pertinent to the questions. As previously described, the technical experts were consulted during the development of inclusion and exclusion criteria. In evaluating titles and abstracts, the following criteria were used to exclude articles from further consideration:

- published prior to 1980

- not in English

- did not include human data

- contained no original data

- a meeting abstract only (no full article for review)

- not relevant to minority health

- no intervention

- not targeted to healthcare providers or organizations

- no evaluation of an intervention

- article did not apply to any of the study questions

The following additional exclusion criteria were applied to articles addressing Question 1 or strategies to improve minority healthcare quality:

- not a randomized controlled trial or a concurrent (non-historical) controlled trial

- not conducted in the United States

The rationale for these was to focus on studies that were more likely to provide valid evidence on the effectiveness of interventions and that could be applied to the healthcare system in the United States. Strategies employed in other countries may only apply to the healthcare systems in those countries and may not be amenable to translation to the healthcare system in the United States. This restriction was not placed on articles addressing Question 2 since it was felt that educational methods and other strategies to improve cultural competence were likely to be applicable to providers in the United States. We did not apply any study design limits on articles addressing Question 2 because preliminary search results indicated that very few of these studies would meet the more stringent criteria.

Finally, for Question 1 the exclusion criterion of “not relevant to minority health” was further specified to focus our review on interventions applicable to quality in minority healthcare. A study was excluded if less than 50 percent of the patients was from a single minority group or multiple minority groups, or if no subgroup analysis based on racial or ethnic group was completed.

Abstract Review Process

Titles and abstracts of all articles retrieved by the literature search were printed on an abstract form and distributed to two reviewers (Appendix B). The reviewers screened the abstracts for eligibility and classified them by the research question addressed. When reviewers agreed there was insufficient information to decide eligibility, the full article was retrieved for review.

The results of the abstract review process were entered into the Minority Health Citations Database. Deleted citations were tagged with the reason for exclusion. Citations were returned to the reviewers for adjudication if they disagreed on eligibility.

Article Review

The purpose of the article review was to confirm the relevance of each article to the research questions, to determine methodological characteristics pertaining to study quality, and to collect evidence pertinent to the research questions.

Quality Assessment and Data Abstraction

Forms were developed to confirm eligibility for full article review, assess study characteristics, and extract the relevant data for the study questions. The forms were developed through an iterative process that included the review of forms used for previous EPC projects, discussions among team members and experts, and pilot testing. This process was challenging because of the heterogenous literature. We developed separate forms to abstract data for each question. We used one form to assess the quality of each study. The forms were color coded to aid reviewers (Appendix B).

Study Quality Assessment

The study quality assessment form had three sections, and reviewers completed the form for each study. The first section included the exclusion criteria so that reviewers could confirm the eligibility of the article before proceeding with the full article review. The second section listed the research questions, thus allowing reviewers to tag articles by the question addressed. The final section contained questions designed to provide an assessment of study quality. These questions were designed to assess methodological strengths and weaknesses in several domains: 1) representativeness of targeted healthcare providers and, if appropriate, targeted patients; 2) potential bias and confounding; 3) description of the intervention; 4) outcomes of the intervention; and 5) analytic approach, statistical quality, and interpretation. In terms of generalizability, studies were given credit for adequately describing their populations, but no judgment was made about whether those populations were representative of the broader population of minority patients or their providers. Each item was scored for each study with a value ranging from 0 to 2. We calculated percentage scores for each domain by adding the total value of the responses and dividing by the total number of possible points for that domain and for that article (excluding items that were not applicable to certain study design types). We used the scores to categorize quality assessment for presentation on the evidence tables. For each domain, scores of 80 percent or higher were given a full circle, scores of 50 to 79 percent were given a half-filled circle, and scores of less than 50 percent were given an empty circle.

Data Abstraction

We used a separate form for each question to abstract information such as study design, intervention, and outcome assessment. For articles addressing Question 1, an additional group description form was completed for each group (or “arm”) in the study. Articles addressing Question 1 were categorized as addressing specific clinical areas by using the IOM list of priority areas 20. We further classified these articles by the IOM framework of consumer perspectives of healthcare needs that included the categories of staying healthy, getting better, living with illness, and coping with the end of life.9

Article Review Process

A serial article review process was employed. In this process, the quality assessment and abstraction forms were completed by the primary reviewer. The second reviewer, after reading the article, checked each item on the forms for completeness and accuracy. The second reviewer also scanned the reference lists of eligible articles to identify potentially relevant articles. The reviewer pairs were formed to include personnel with domain-specific and/or methodological expertise.

All information from the article review process was entered in a relational database (Minority Health Evidence Database). The database was used to maintain and clean the data, as well as to create evidence and summary tables.

Grading of the Evidence

After all articles were reviewed, the quality of the evidence supporting each question was graded on the basis of its quality, quantity, and consistency (see Table 1). In terms of quality, the articles were examined by two criteria: study design and the presence of an objective assessment of outcomes. To meet the quality criteria for Grade A, there must have been at least one randomized controlled trial and at least 75 percent of the studies must have used an objective assessment method. To meet the quality criteria for Grade B, there must have been at least one controlled trial (not necessarily randomized) AND at least 50 percent of studies must have used an objective assessment method. To meet the quality criteria for Grade C or D, there did not need to be any controlled trials and less than 50 percent of studies could have used an objective assessment to measure outcomes.

In terms of quantity, there had to be at least four studies to meet criteria for Grade A, three to meet the criteria for Grade B, two to meet the criteria for Grade C, or fewer than two studies to meet the criteria for Grade D. In terms of consistency, the results of the studies had to be consistent to meet the criteria for Grade A, reasonably consistent to meet the criteria for Grade B, and inconsistent to meet the criteria for Grade C. Where there where too few studies to judge the consistency the article was assigned Grade D. The grading of the evidence was discussed at a team meeting and consensus was reached on each criterion. The evidence received a final “grade” that reflected the lowest rank on each of the four criteria (two for quality and one each for quantity and consistency).

Peer Review

Throughout the project, feedback was sought from the technical experts through formal and ad hoc requests for guidance. A draft of the completed report was sent to the technical experts, as well as to the partner (NQF), AHRQ and other peer reviewers. Substantive comments were catalogued and entered into a database. Revisions were made to the evidence report as warranted, and a summary of the comments and their disposition was submitted to AHRQ with the final report.

Figures

Figure 1. Analytic framework (with intervention targets circled)

Adapted from Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:477–486 with copyright permission (pending) from the Society of General Internal Medicine.