All rights reserved. NICE copyright material can be downloaded for private research and study, and may be reproduced for educational and not-for-profit purposes. No reproduction by or for commercial organisations, or for commercial purposes, is allowed without the written permission of NICE.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Alliance (UK). Mental Health Problems in People with Learning Disabilities: Prevention, Assessment and Management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2016 Sep. (NICE Guideline, No. 54.)

Abbreviations

- AAMD

American Association for Mental Deficiency (now American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities)

- ABA

applied behaviour analysis

- ADAS

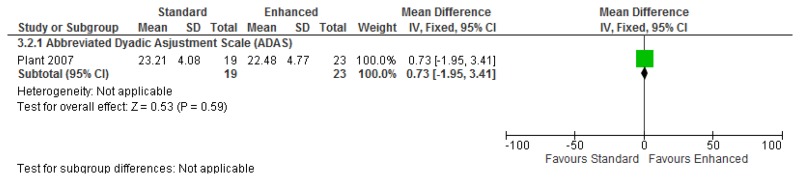

Abbreviated Dyadic Adjustment Scale

- ADHD

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- A-PS

assertiveness training, followed by social problem solving

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- CBT

cognitive behavioural therapy

- CI

confidence interval

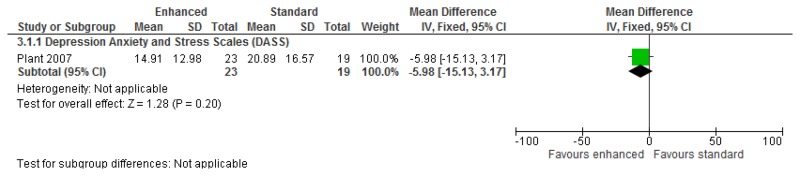

- DASS

Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale

- DC-LD

Diagnostic Criteria for Psychiatric Disorders for Use with Adults with Learning Disabilities/mental Retardation

- DMR

Dementia Questionnaire for Mentally Retarded

- DSDS

Down Syndrome Dementia Scale

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition)

- DSQIID

Dementia Screening Questionnaire for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities

- FN

false negatives

- FP

false positives

- GHQ30

General Health Questionnaire (30 item)

- ICD-10

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th edition)

- IV

Inverse variance method

- KPS-SF

Kansas Parental Satisfaction Scale – Short Form

- MASS

Mood and Anxiety Semi-structured Interview

- M-H

Mantel-Haenszel method

- NADIID

Neuropsychological Assessment of Dementia in Intellectual Disabilities

- PAS-ADD

Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with a Developmental Disability

- PS-A

social problem solving, followed by assertiveness training

- PSI (-SF)

Parenting Stress Index (-Short Form)

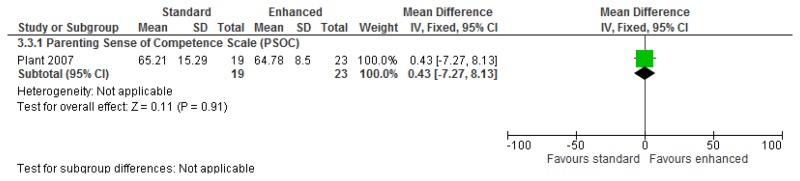

- PSOC

Parenting Sense of Competence Scale

- QoL

quality of life

- RCT

randomised controlled trial

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SAS-ID

Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities

- SD

standard deviation

- SDQ

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SE

standard error

- SF-12

Short Form Health Survey

- SIB-R

Severe Impairment Battery – Revised

- SNAP-IV

Swanson, Nolan and Pelham Questionnaire (version 4)

- SSTP

Stepping Stones Triple-P

- STATE-A

state anxiety

- TAU

treatment as usual

- TN

true negatives

- TP

true positives

- TRAIT-A

trait anxiety

- VABS

Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales

O.1. Measures to assess mental health needs among people with learning disabilities

O.1.1. General measures of mental health

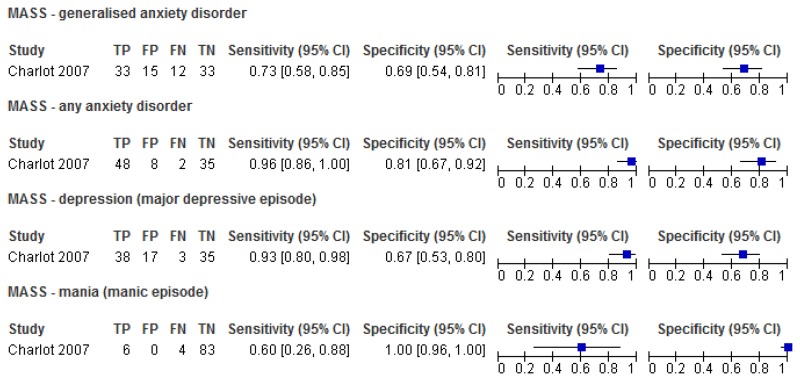

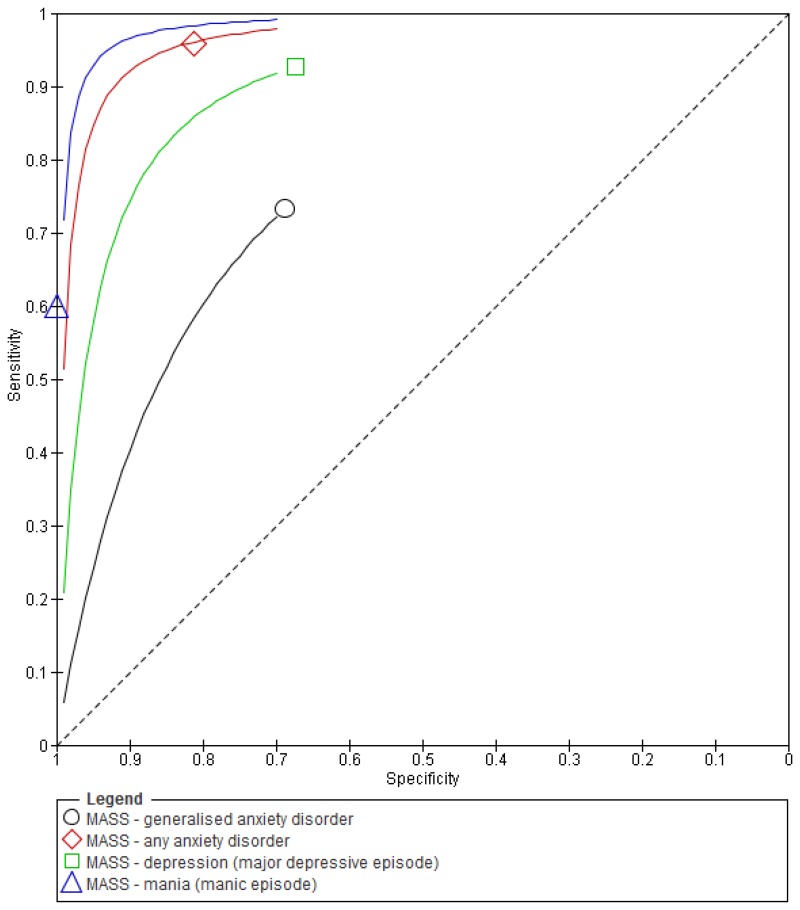

O.1.1.1. Mood and Anxiety Semi-Structured Interview (MASS)

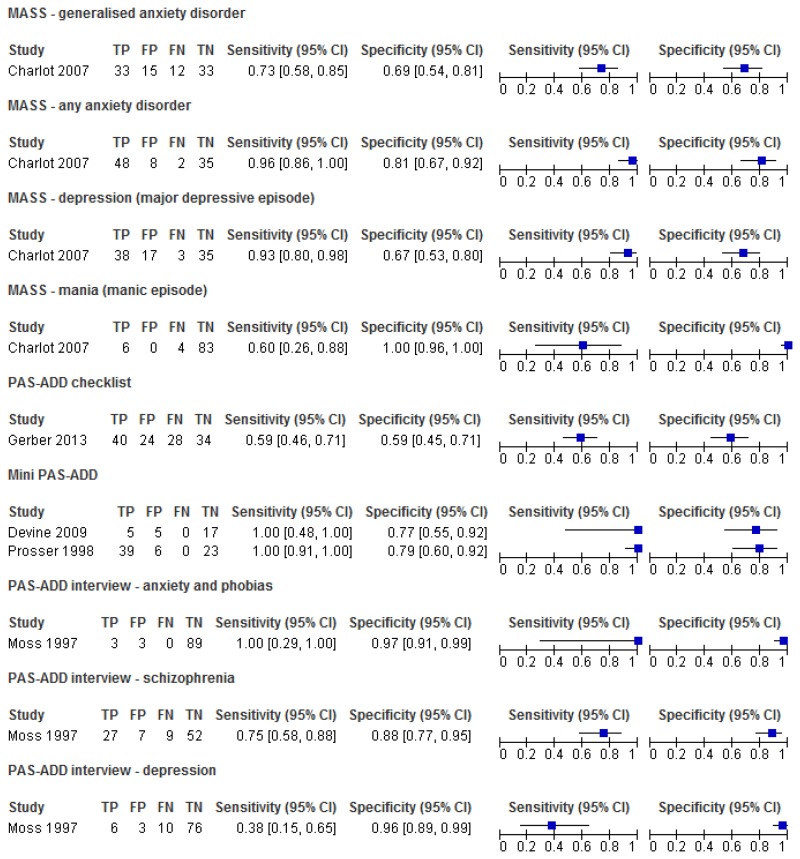

Figure 1Sensitivity and specificity of the MASS for the detection of mental health problems among adults with learning disabilities

O.1.1.2. Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disabilities (PAS-ADD) – Interview

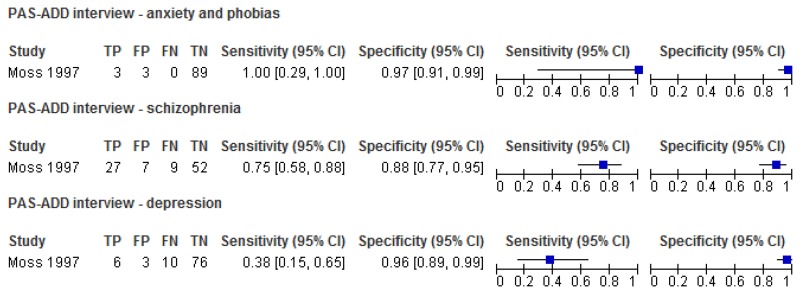

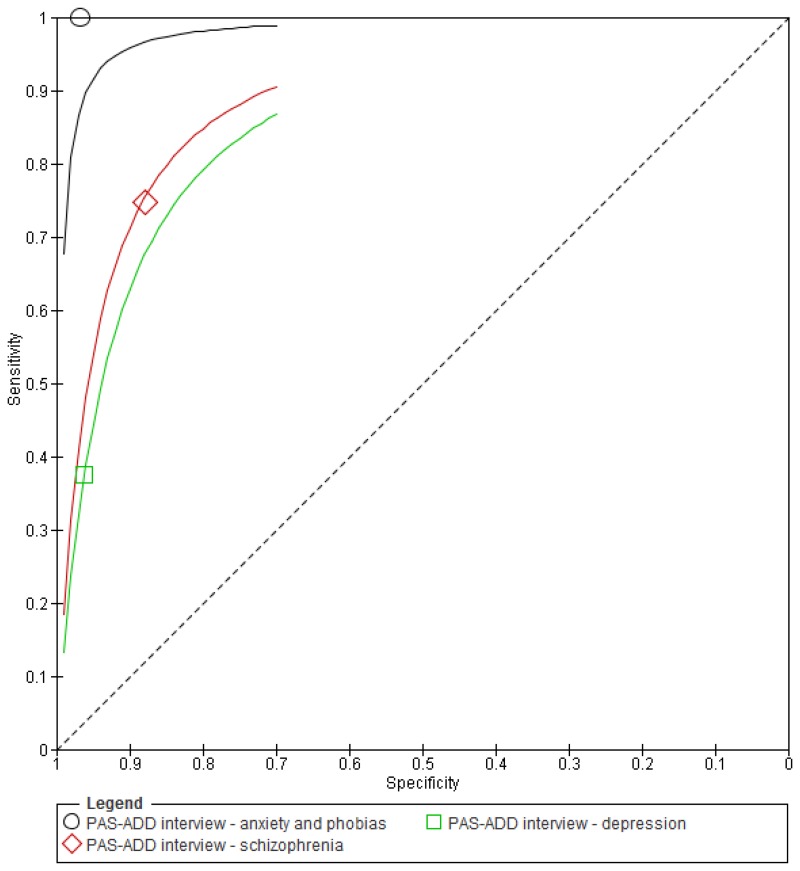

Figure 3Sensitivity and specificity of the PAS-ADD Interview for detecting mental health problems in adults with learning disabilities

O.1.1.3. Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disabilities (PAS-ADD) – Checklist

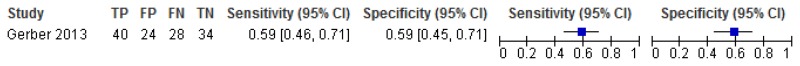

Figure 5Sensitivity and specificity of the PAS-ADD Checklist for the detection of mental health problems among adults with learning disabilities

O.1.1.4. Psychiatric assessment schedule for adults with developmental disabilities (PAS-ADD) – Mini

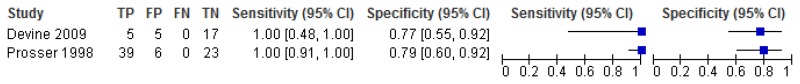

Figure 7Sensitivity and specificity of the Mini PAS-ADD for the detection of mental health problems in adults with learning disabilities

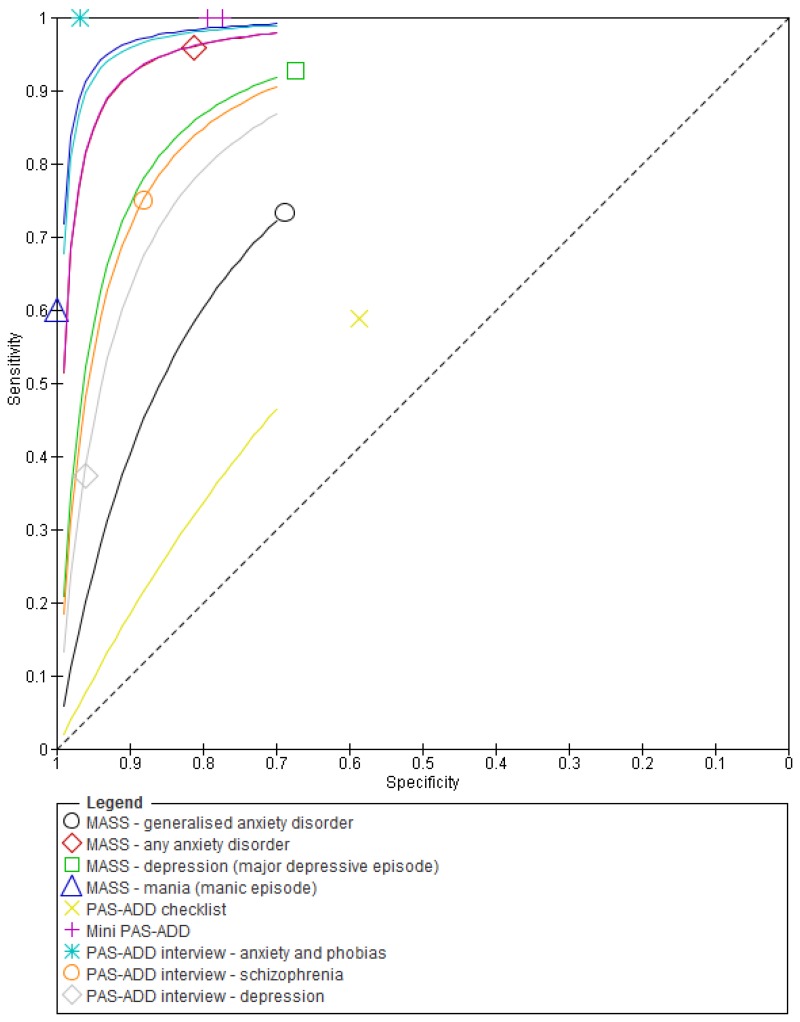

O.1.1.5. Comparison between different tools used to identify mental health problems in adults with learning disabilities

Figure 9Sensitivity and specificity of different tools used to identify mental health problems in adults with learning disabilities

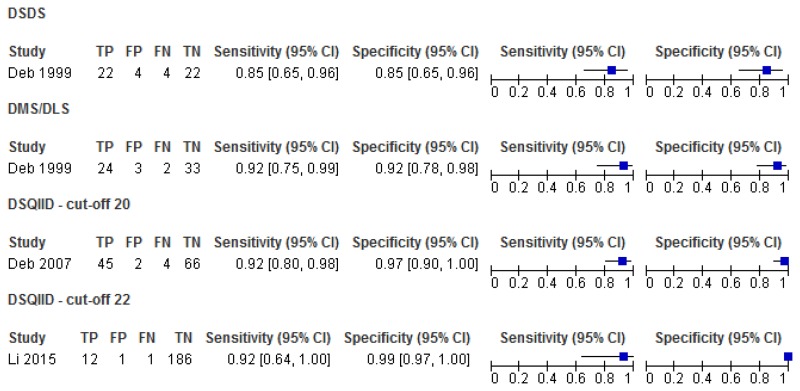

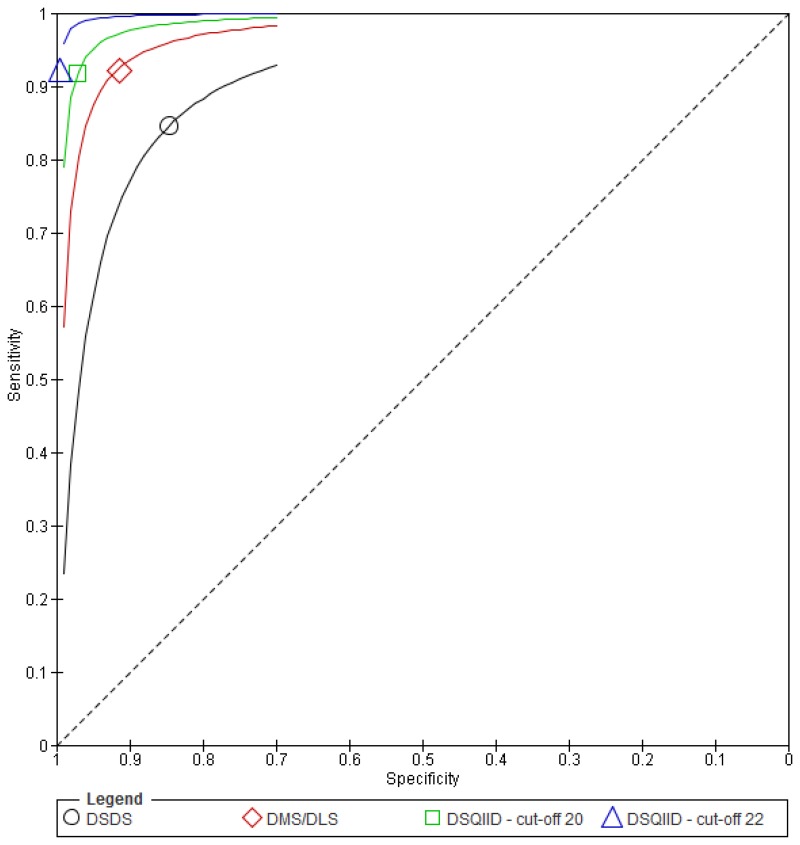

O.1.2. Dementia

O.1.2.1. Dementia Screening Questionnaire for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities (DSQIID), Dementia Questionnaire for Mentally Retarded (DMR) and Down Syndrome Dementia Scale (DSDS)

Figure 11Sensitivity and specificity of the DSQIID, DMR and DSDS for detecting symptoms of dementia in people with learning disabilities

O.2. Psychological interventions

O.2.1. Mixed mental health problems

O.2.1.1. Mild to moderate learning disabilities

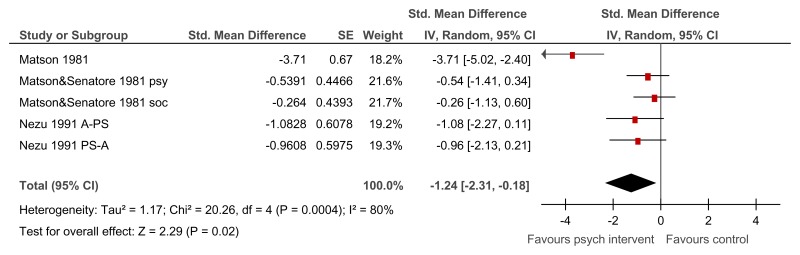

Figure 13Psychological intervention versus control (RCTs) – mental health measured with various scales (after mean 13.25 weeks of treatment)

Various scales used including Overall fear rating, Nurses’ Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation (NOSIE-30), Brief Symptom Inventory; random-effects model used because of unexplained heterogeneity

Figure 14Psychological intervention versus control (controlled before-and-after studies) – mental health (Brief Symptom Inventory: Global Severity Index, after 12 weeks of treatment)

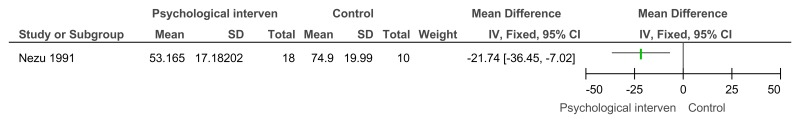

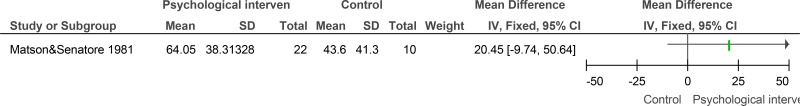

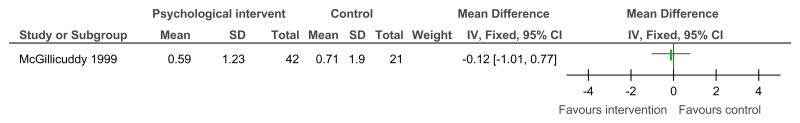

Figure 15Psychological intervention versus control – low problem behaviour (Role-play test of anger arousing situations, after 10 weeks of treatment)

Figure 16Psychological intervention versus control – maladaptive functioning (Adaptive behaviour scale - revised - part II, carer version, after 10 weeks of treatment)

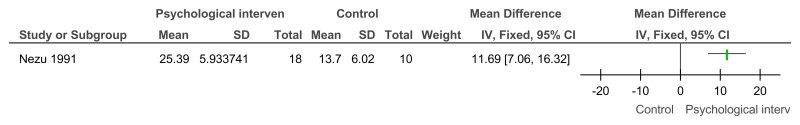

Figure 17Psychological intervention versus control – adaptive functioning -interpersonal skills on the social performance survey schedule after 18 weeks of treatment)

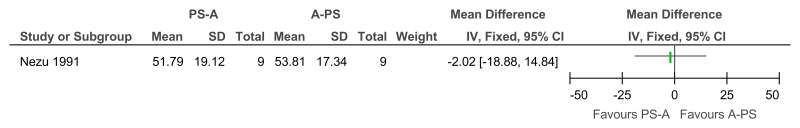

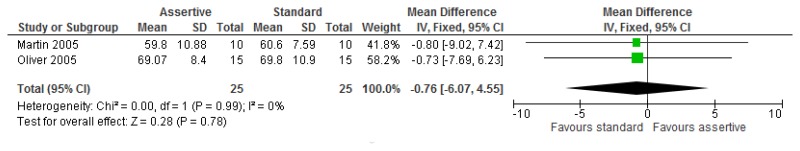

Figure 18Social problem solving then assertiveness training versus assertiveness training followed by social problem solving – mental health (Brief Symptom Inventory, after 3 months’ follow-up)

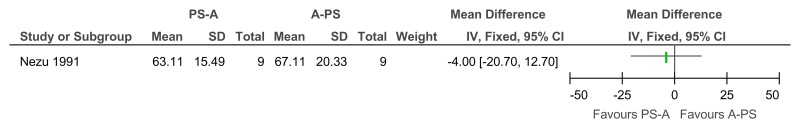

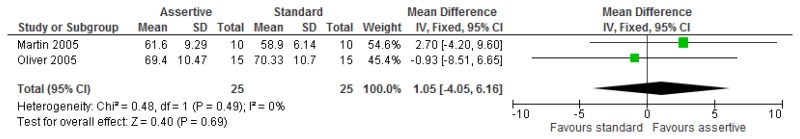

Figure 19Social problem solving then assertiveness training versus assertiveness training followed by social problem solving – maladaptive behaviour (Adaptive Behavior Scale-Revised, after 3 months’ follow-up)

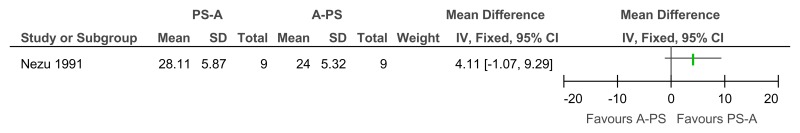

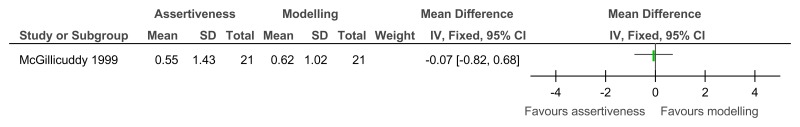

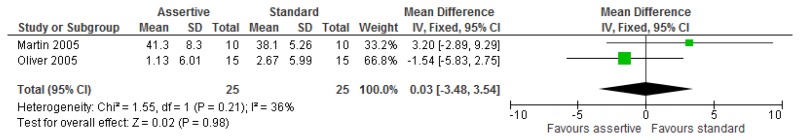

Figure 20Social problem solving then assertiveness training versus assertiveness training followed by social problem solving – adaptive behaviour (problem-solving task, after 3 months’ follow-up)

O.2.2. Substance misuse

O.2.3. Anxiety disorders

O.2.3.1. Anxiety symptoms

O.2.3.1.1. Mild to moderate learning disabilities

Figure 24Any psychological intervention versus control (RCTs) – anxiety symptoms (various scales at 42 weeks follow-up)

Various scales used – modified Beck’s anxiety inventory and modified Zung anxiety scale; random-effects model used because of unexplained heterogeneity

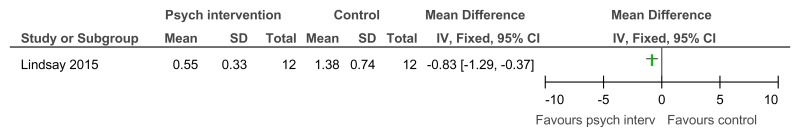

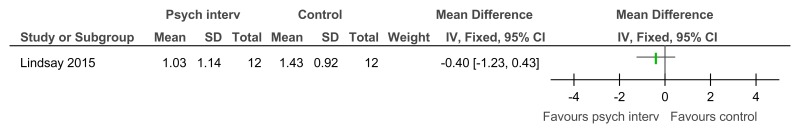

Figure 25Any psychological intervention versus control (controlled before-and-after study) – anxiety symptoms (Brief Symptom Inventory: anxiety symptom dimension after 12 weeks follow-up)

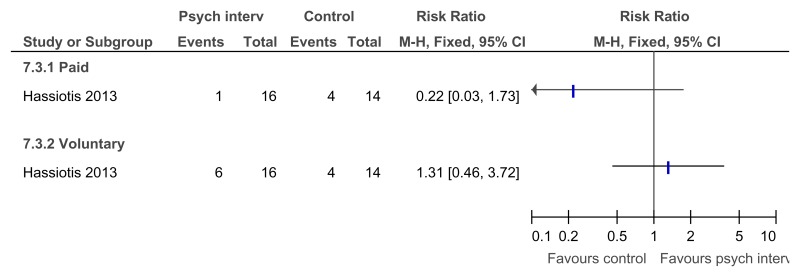

Figure 26Any psychological intervention versus control – in employment after treatment (16 weeks after treatment)

Figure 27Any psychological intervention versus control – hours per week in paid employment after treatment (16 weeks after treatment)

O.2.3.1.2. Moderate to severe learning disabilities

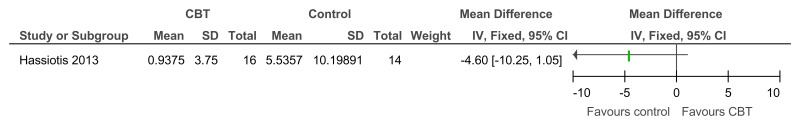

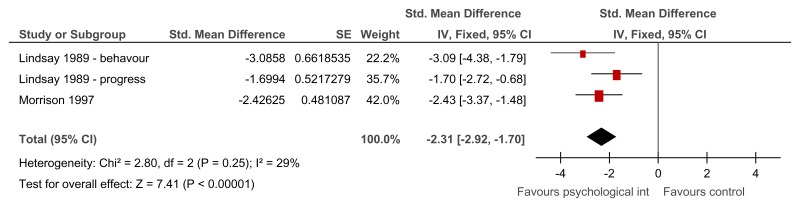

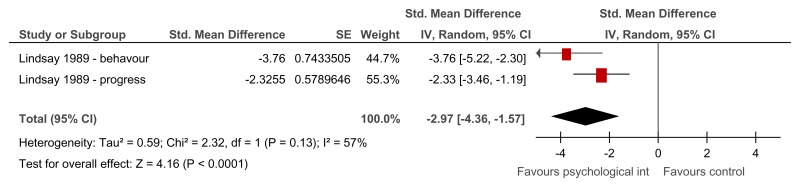

Figure 29Group relaxation training versus control – anxiety symptoms on various scales (after treatment – 2.29 weeks or unclear)

Various scales used – Behavioural anxiety scale and modified Zung anxiety scale; SMD estimated from t-value for Lindsay 1989

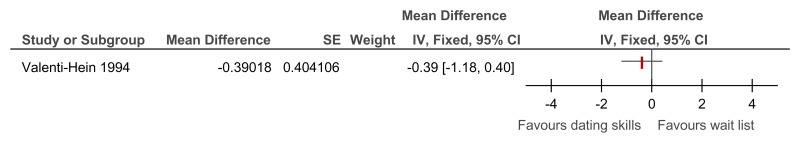

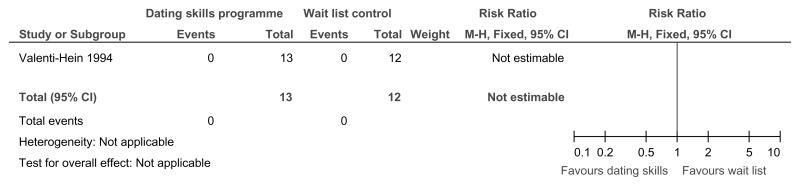

O.2.3.2. Social anxiety symptoms

O.2.4. Depressive symptoms

O.2.4.1. Mild to moderate learning disabilities

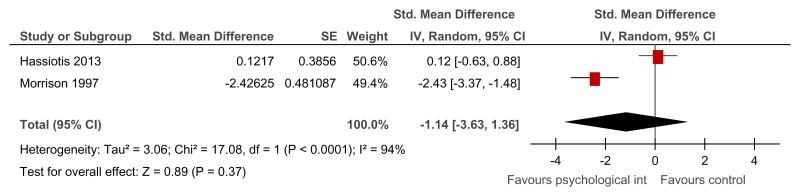

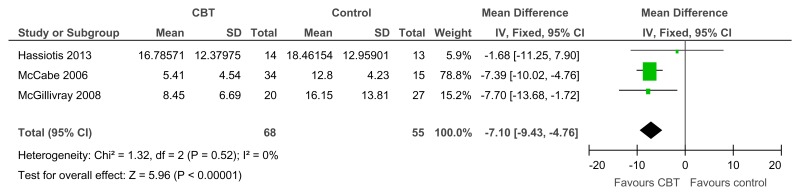

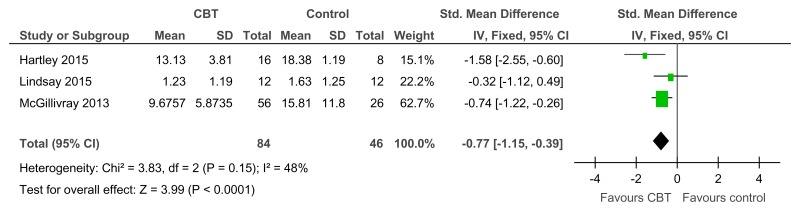

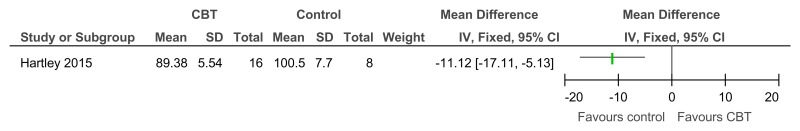

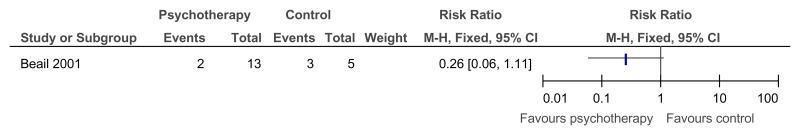

Figure 35CBT versus control – depressive symptoms (various scales; from 12 to 46.7 weeks)

Various scales used including BDI, GDS-LD, and depression subscale on Brief Symptom Inventory Source

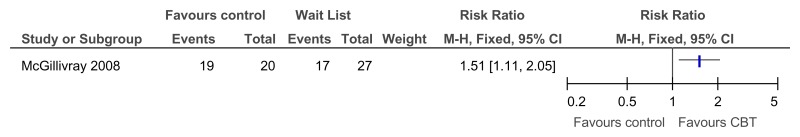

Figure 36CBT versus control – at least small improvement in depressive symptoms on BDI (RCT, 12 weeks)

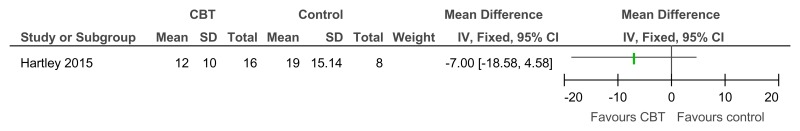

Figure 37CBT versus control – problem behaviour on the SIB-R (controlled before-and-after; 23 weeks)

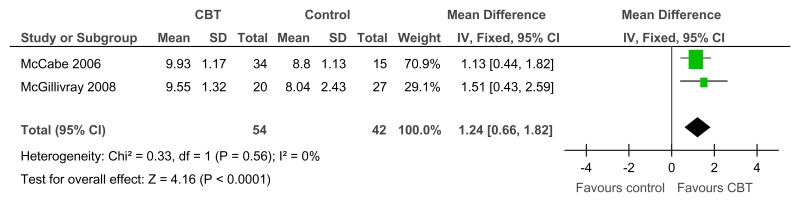

Figure 38CBT versus control – social skills (adaptive functioning on the Social Comparison Scale, RCT, 6–12 weeks)

Figure 39CBT versus control – social behaviours (adaptive functioning, controlled before-and-after study, 23 weeks)

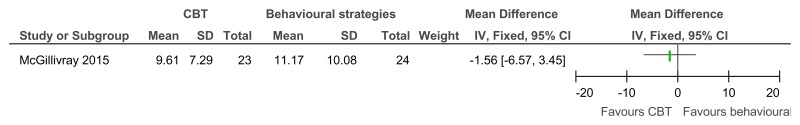

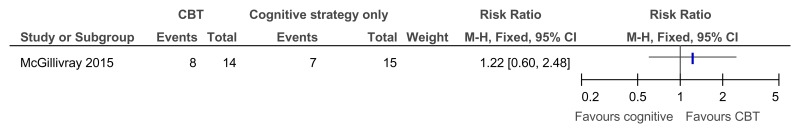

Figure 41CBT versus behavioural strategies only – improvement in those with clinical depression at baseline (reduced score on BDI II at 38 weeks)

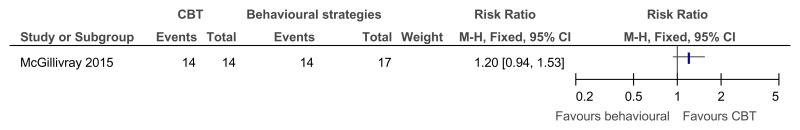

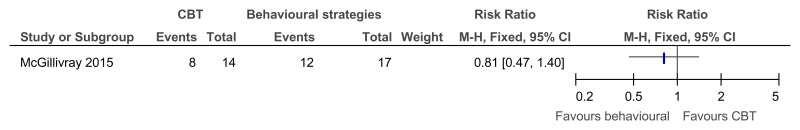

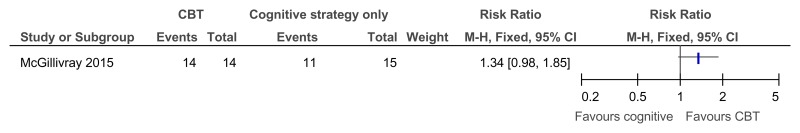

Figure 42CBT versus behavioural strategies only – recovery in those with clinical depression at baseline (score 13 or less on BDI II at 38 weeks)

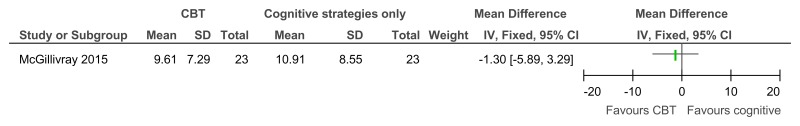

Figure 44CBT versus cognitive strategies only – improvement in those with clinical depression at baseline (reduced score on BDI II, 38 weeks)

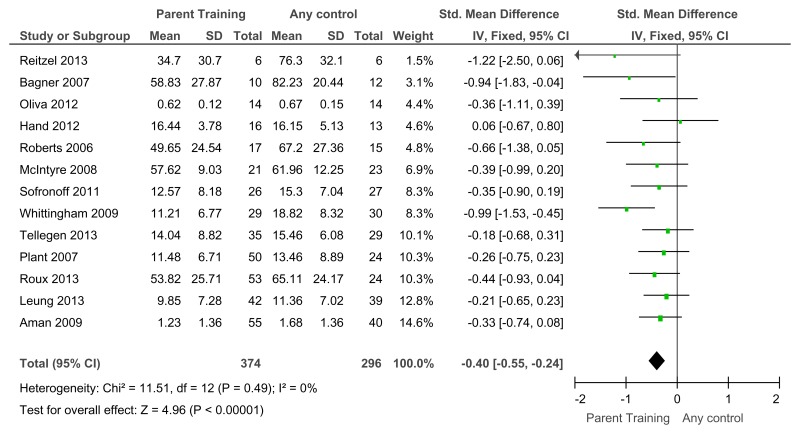

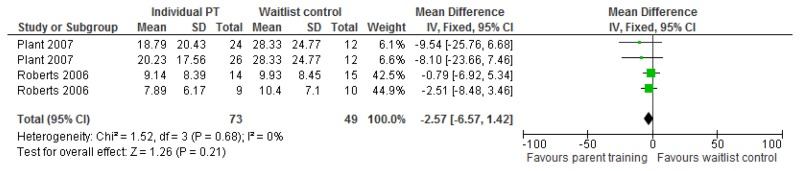

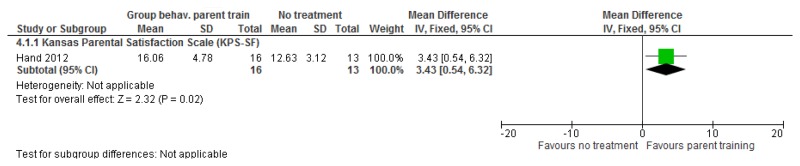

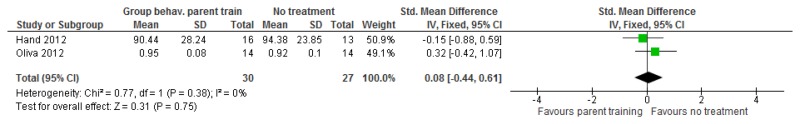

O.3. Parent training interventions aimed at reducing and managing behaviour that challenges

Figure 47 was amended from the challenging behaviour guideline and has therefore been included in this appendix. However for all other forest plots relating to the effectiveness of parent training please refer to the appropriate appendix in the challenging behaviour guideline.

O.3.1. Parent training versus any control

Figure 47Mental health (severity, various scales) – post-treatment

Various scales included DBC-total score, CBCL – total score, Parent Symptom Questionnaire, SDQ – total score, Home Situations Questionnaire (severity), ECBI – problem subscale, 2 studies did not report a total score on the DBC so the disruptive behaviour score was used.

O.4. Pharmacological interventions for prevention and/or treatment

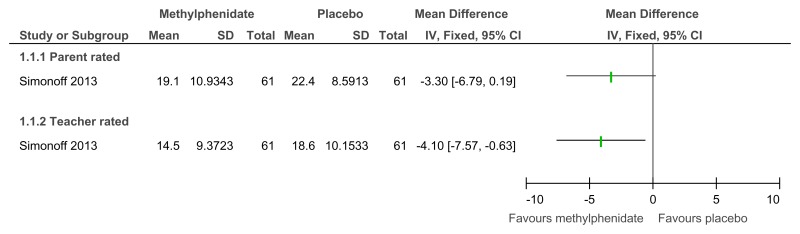

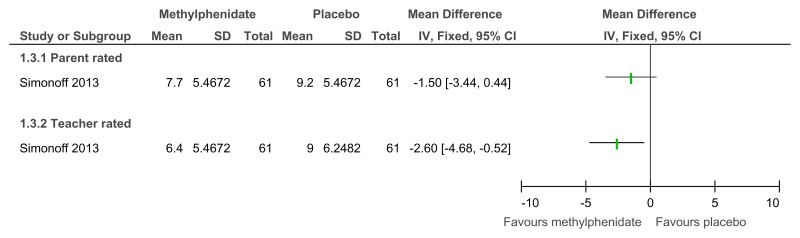

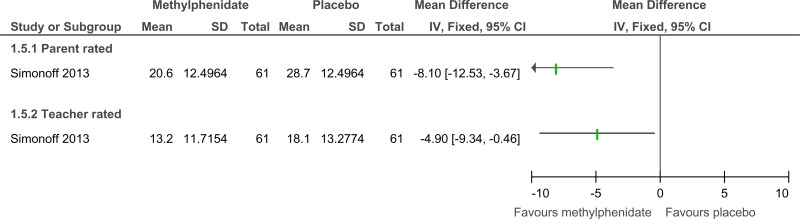

O.4.1. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and young people

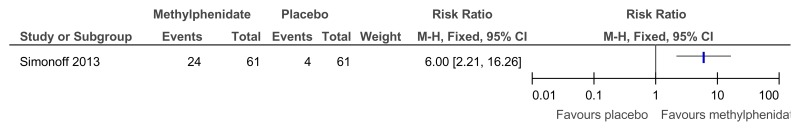

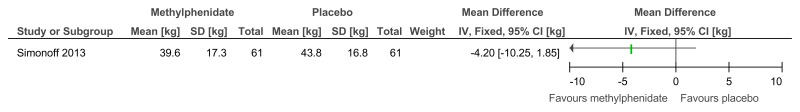

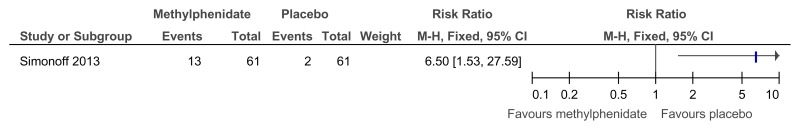

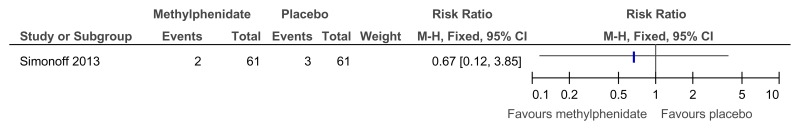

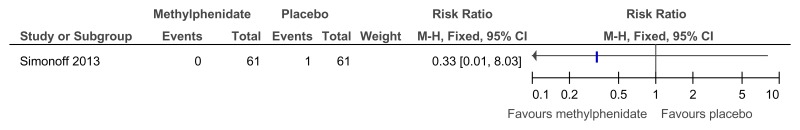

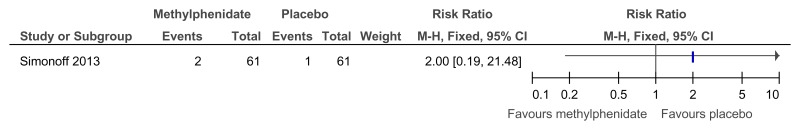

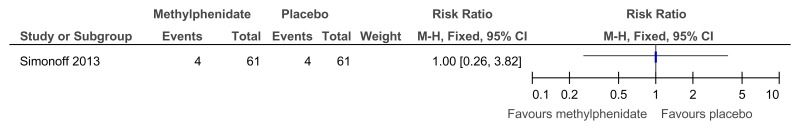

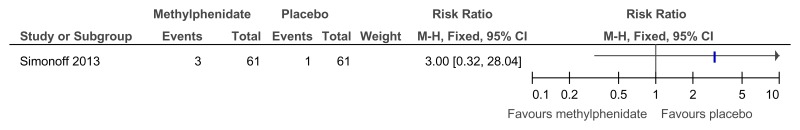

Figure 48Methylphenidate versus placebo – mental health (ADHD symptoms at 16 weeks measured with the Conners ADHD Index)

Figure 49Methylphenidate versus placebo – mental health (hyperactivity at 16 weeks measured with the Conners hyperactivity scale)

Figure 50Methylphenidate versus placebo – mental health (hyperactivity at 16 weeks measured with Aberrant Behavior Checklist)

Figure 51Methylphenidate versus placebo – mental health (‘improved’ or ‘better’ on Clinical Global Impressions scale at 16 weeks)

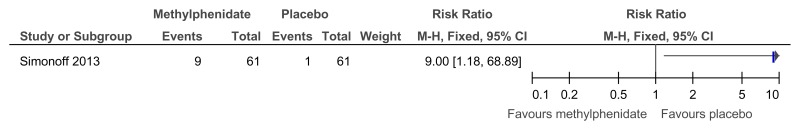

Figure 58Methylphenidate versus placebo – side effects (meaningless repetitive behaviour at 16 weeks)

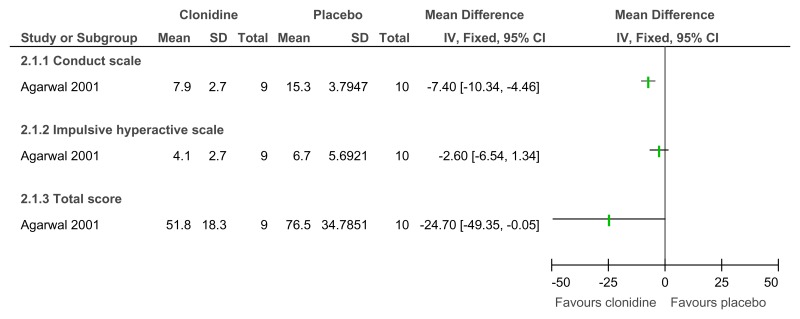

Figure 60Clonidine versus placebo – mental health (ADHD symptoms on Conners Parent scale at 6 weeks)

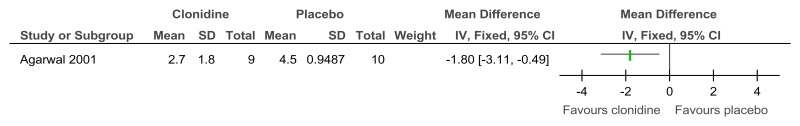

Figure 61Clonidine versus placebo – mental health (ADHD symptoms on Clinical Global Impression Scale at 6 weeks)

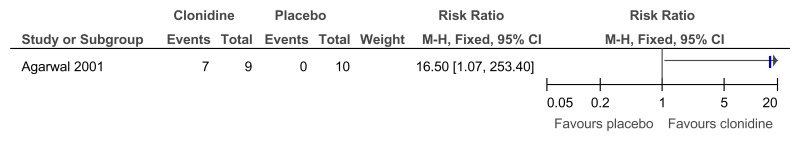

Figure 62Clonidine versus placebo – mental health (much or very much improved ADHD symptoms on Clinical Global Impression Scale at 6 weeks)

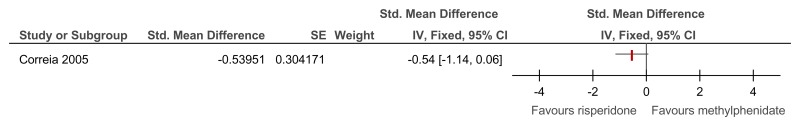

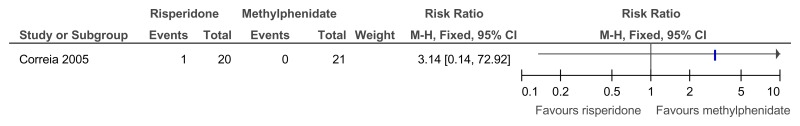

Figure 63Risperidone versus methylphenidate – ADHD symptoms (measured on SNAP-IV total score at 4 weeks)

SMD estimated from F-value

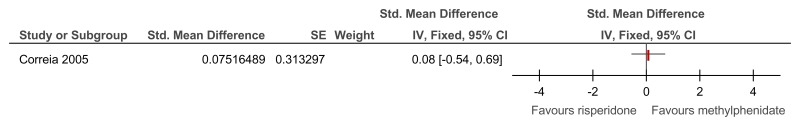

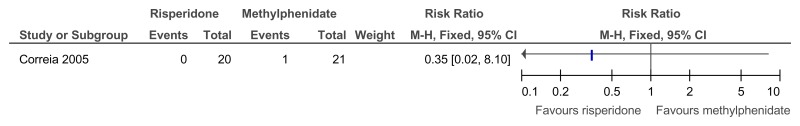

Figure 64Risperidone versus methylphenidate – side effects (measured on Barkley’s Side Effects Rating Scale at 4 weeks)

SMD estimated from F-value

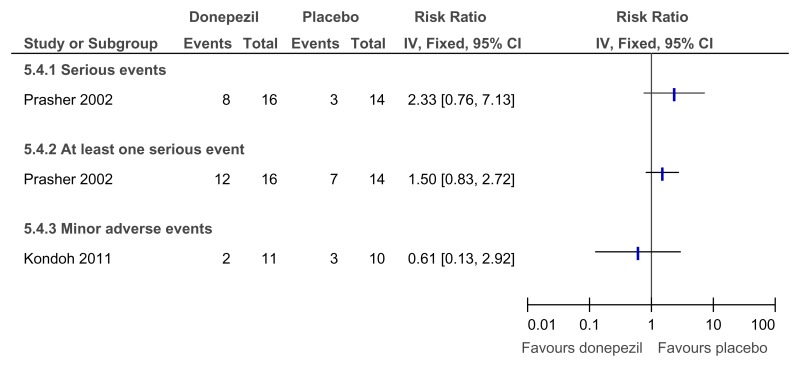

O.4.2. Dementia

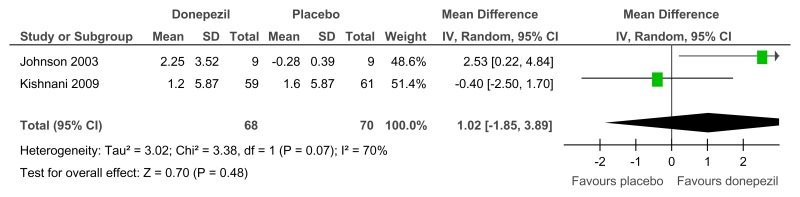

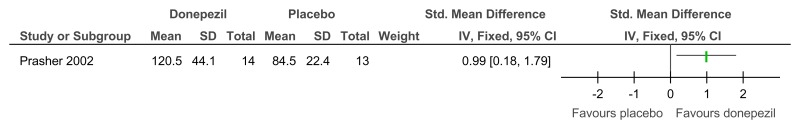

Figure 67Donepezil versus placebo (prevention) – cognitive abilities (Severe Impairment Battery; 12 weeks)

Random-effects model used as significant unexplained heterogeneity

Figure 68Donepezil versus placebo (prevention) – behavioural problems (various scales; 12 weeks)

Various scales used included Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised (SIB-R) and Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scale

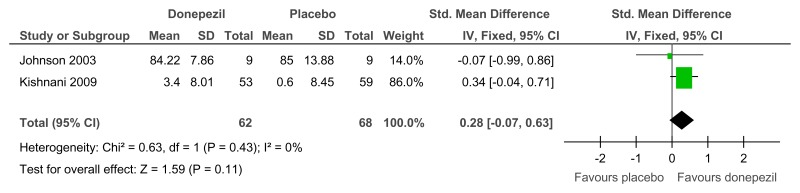

Figure 70Donepezil versus placebo (treatment) – cognitive abilities (Severe Impairment Battery; 24 weeks)

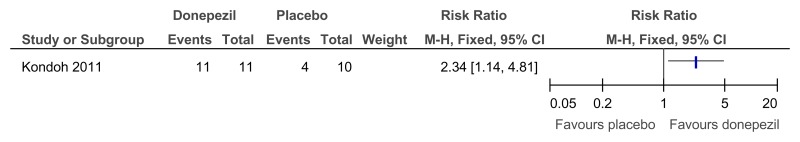

Figure 72Donepezil versus placebo (treatment) – global functioning (proportion with improved impression of quality of life; 24 weeks)

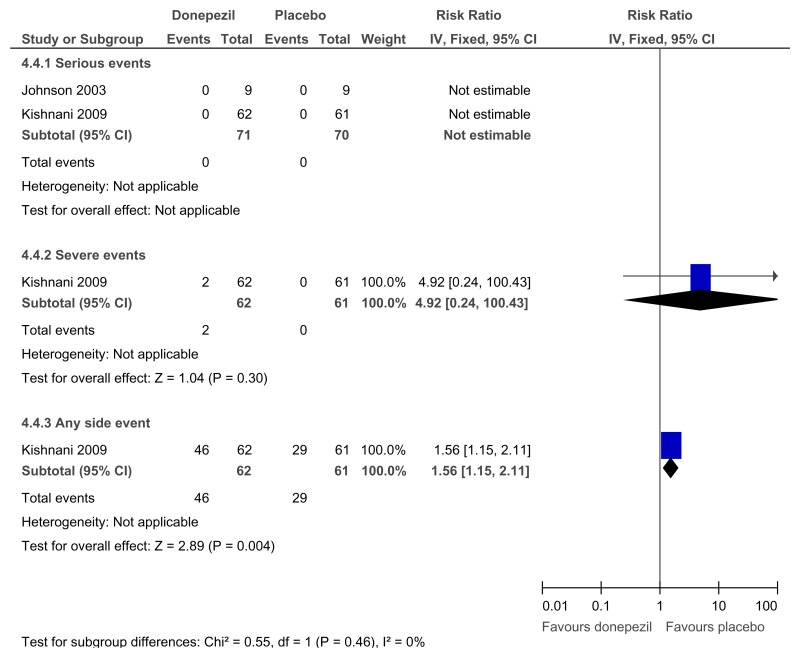

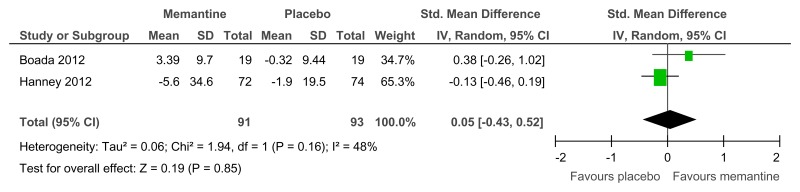

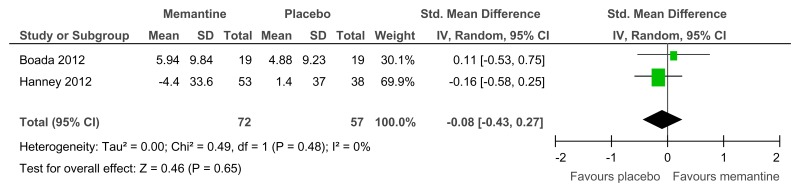

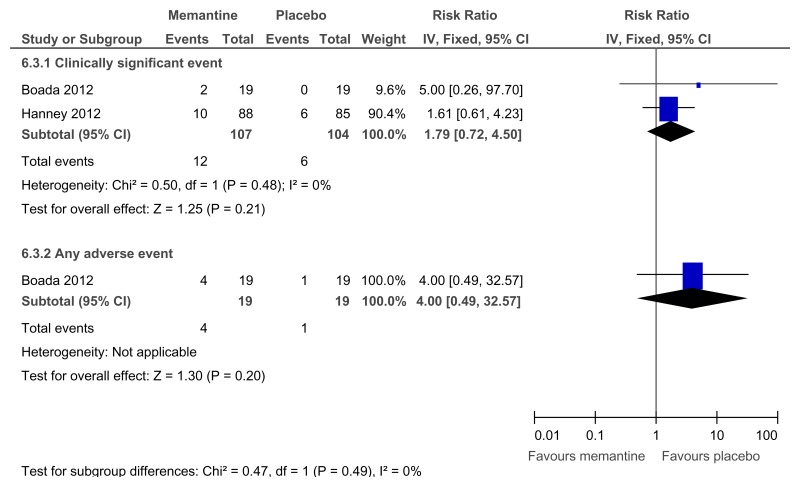

Figure 74Memantine versus placebo (prevention or treatment) – cognitive abilities (various scales, 16–52 weeks)

Figure 75Memantine versus placebo (prevention or treatment) – behavioural problems (various scales, 16–52 weeks)

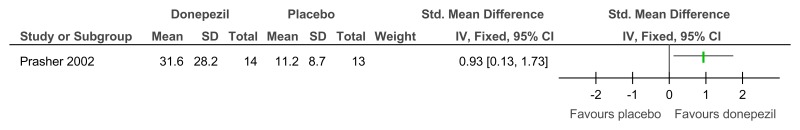

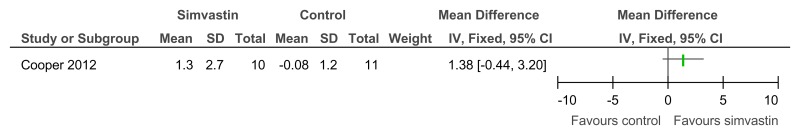

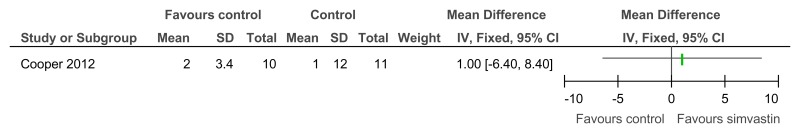

Figure 77Simvastin versus placebo (prevention or treatment) – cognitive abilities (NADIID battery; 52 weeks)

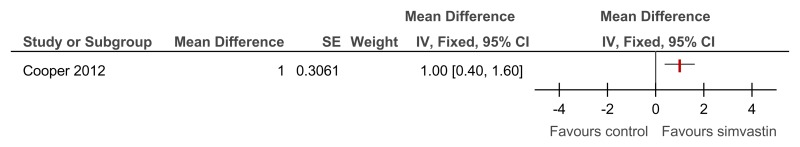

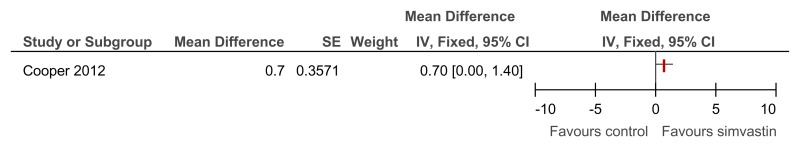

Figure 78Simvastin versus placebo (prevention or treatment) – cognitive abilities (NADIID battery; 52 weeks, adjusted for baseline and stratification values)

O.5. Other interventions

O.5.1. Annual health checks

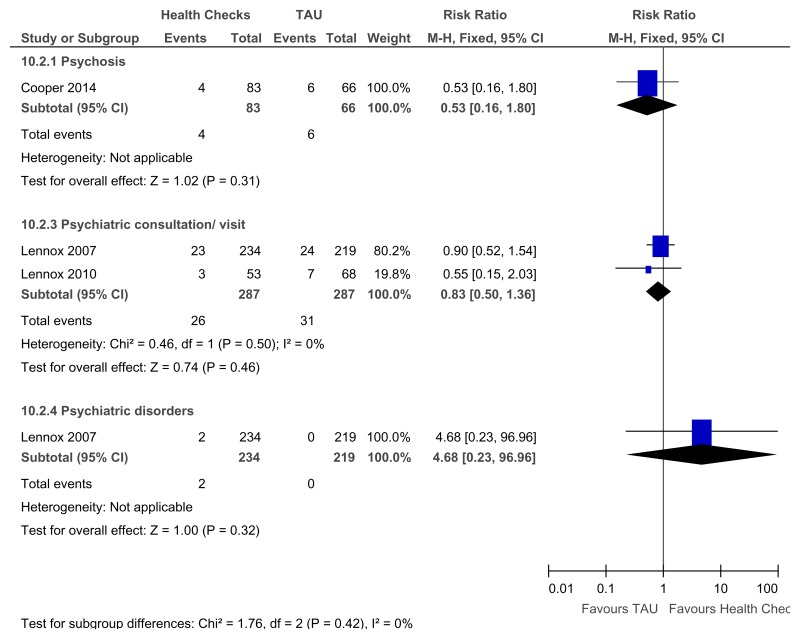

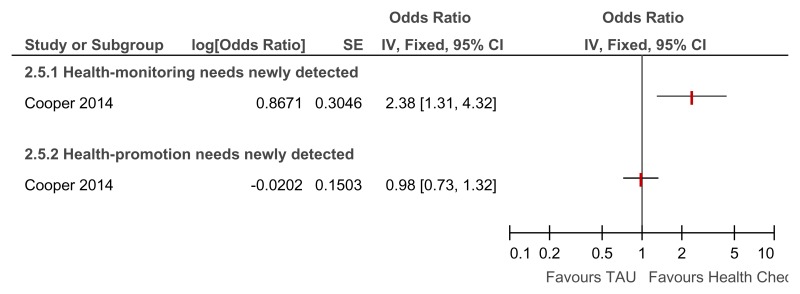

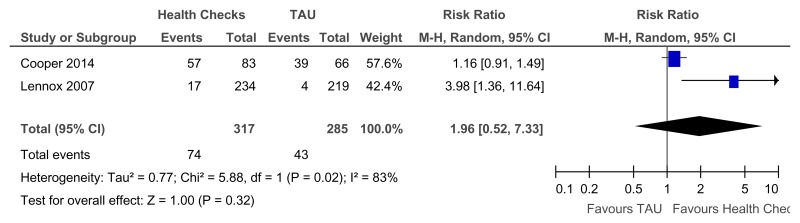

Figure 81Annual health checks versus treatment as usual – Identification of mental health needs for all levels of learning disabilities (Mental health at 39 weeks)

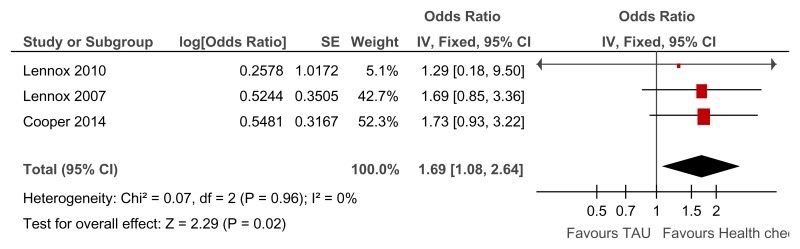

Figure 82Annual health checks versus treatment as usual – Newly detected health issues for all levels of learning disabilities (Quality of life at 39 to 52 weeks)

Overall OR reported rather than RR as one study only reported the OR only and the RR was not calculable

Figure 83Annual health checks versus treatment as usual – Newly detected health monitoring and health promotion needs for all levels of learning disabilities (Quality of life at 39 weeks)

Overall OR reported rather than RR as one study only reported the OR only and the RR was not calculable

O.5.2. Dietary interventions

O.5.2.1. ADHD

O.5.2.2. Unclear level of learning disabilities

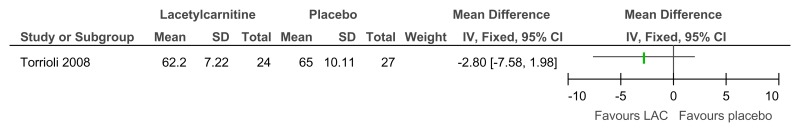

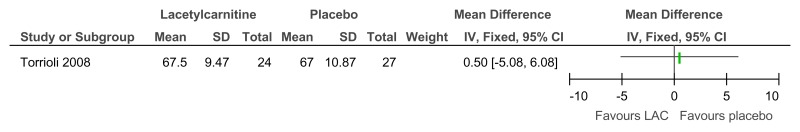

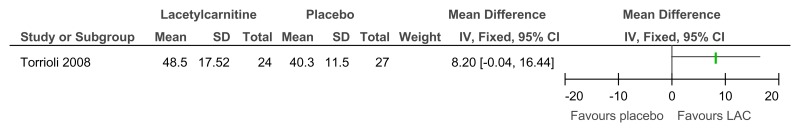

Figure 85L-acetylcarnitine versus placebo for the treatment of ADHD in children with Fragile X syndrome – ADHD symptoms (mental health; Conners Parents rating scale; 52 weeks)

Figure 86L-acetylcarnitine versus placebo for the treatment of ADHD in children with Fragile X syndrome – ADHD symptoms (mental health; Conners Teachers rating scale; 52 weeks)

Figure 87L-acetylcarnitine versus placebo for the treatment of ADHD in children with Fragile X syndrome – adaptive functioning (VABS – full scale; 52 weeks)

O.5.2.3. Dementia

O.5.2.3.1. Mild to moderate learning disabilities

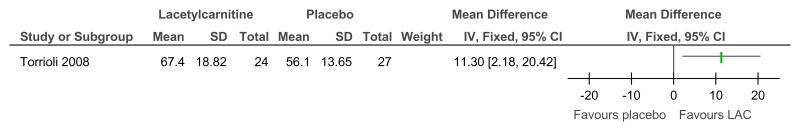

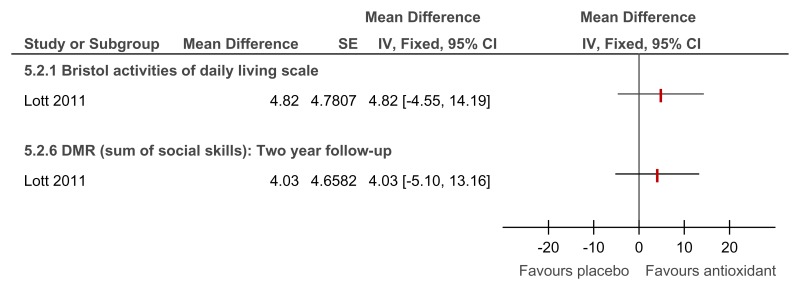

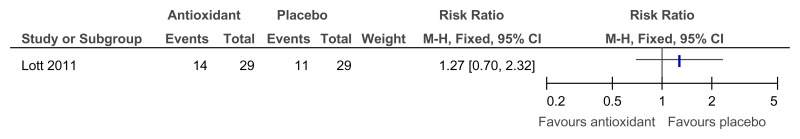

Figure 89Antioxidant versus placebo for the treatment of dementia in people with Down’s syndrome – cognitive abilities (mental health; 2 year follow-up)

Direction of effect not reported in study (only the mean difference in change scores) and author not contactable so the direction of effect was assumed. However, the paper reported that there was no significant difference between groups on these measures.

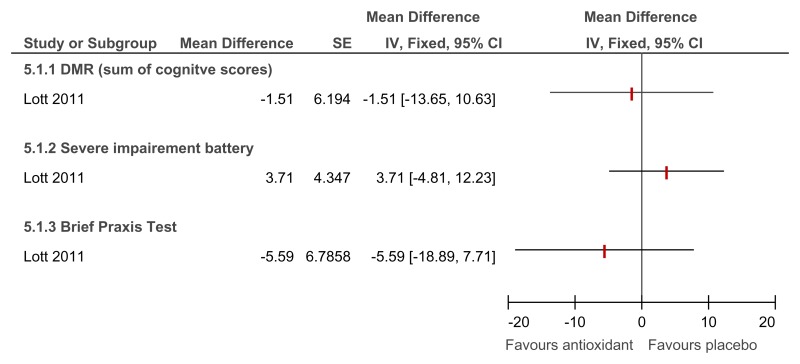

Figure 90Antioxidant versus placebo for the treatment of dementia in people with Down’s syndrome – adaptive functioning (2 year follow-up)

O.5.3. Exercise interventions

O.5.3.1. Anxiety symptoms

O.5.3.1.1. Mild to moderate learning disabilities

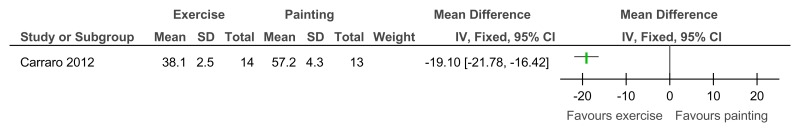

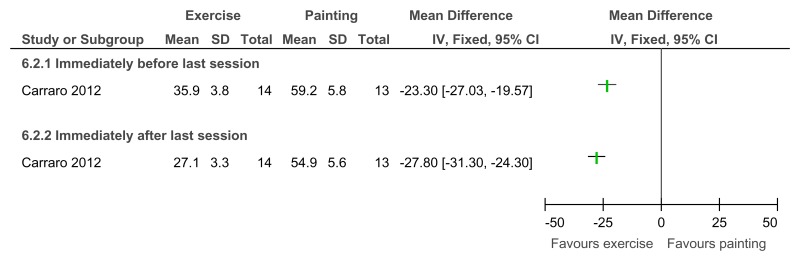

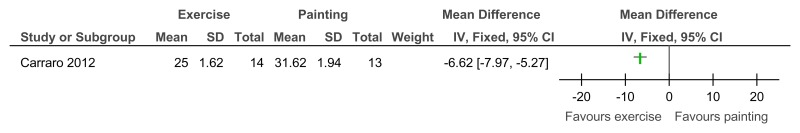

O.5.3.2. Depressive symptoms– mild to moderate learning disabilities

O.5.3.2.1. Mild to moderate learning disabilities

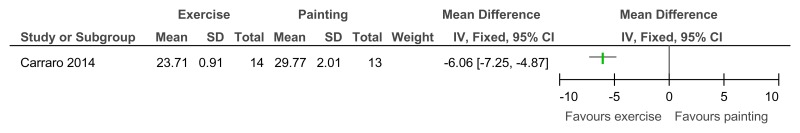

Figure 95Exercise versus painting control – Depressive symptoms (Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale, 12 weeks)

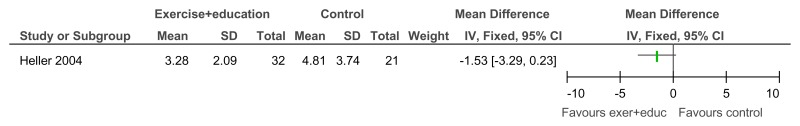

Figure 96Exercise + education versus no treatment – Depressive symptoms (Child Depression Inventory; 12 weeks)

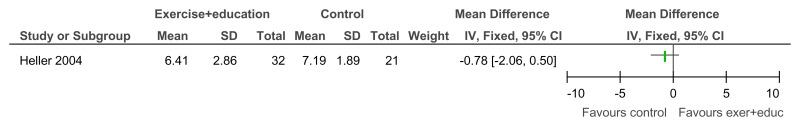

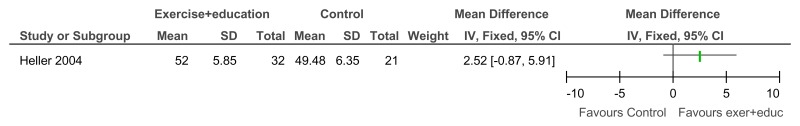

Figure 97Exercise + education versus no treatment – Community participation and meaningful occupation (Community Integration Scale; 12 weeks)

O.6. Organising health care services for people with intellectual disabilities

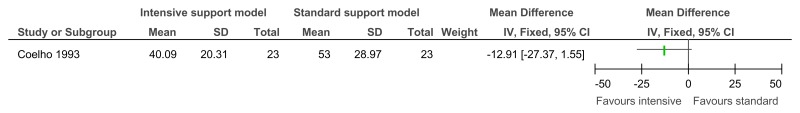

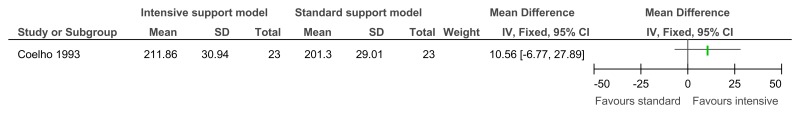

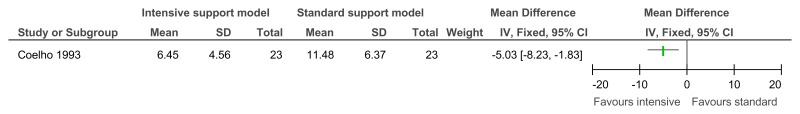

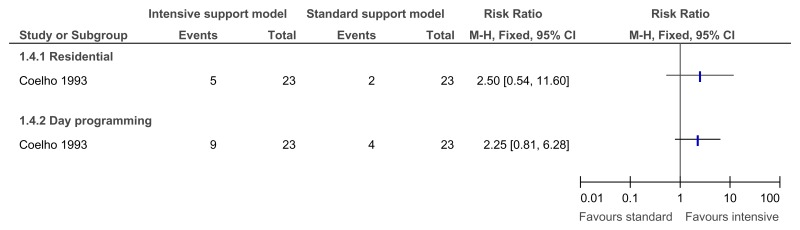

O.6.1. Innovative intensive support services model versus standard model of service delivery

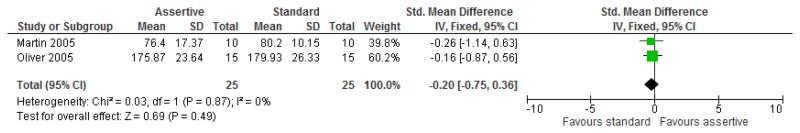

O.6.2. Assertive community treatment versus standard model

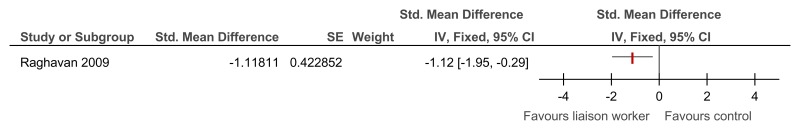

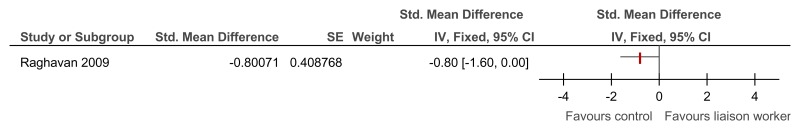

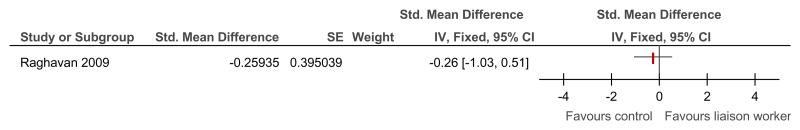

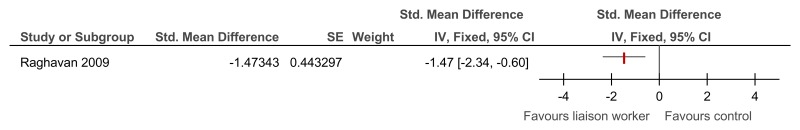

O.6.3. Specialist liaison worker model versus no liaison worker

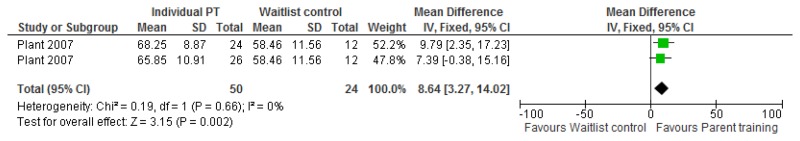

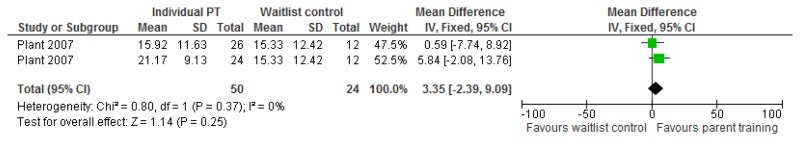

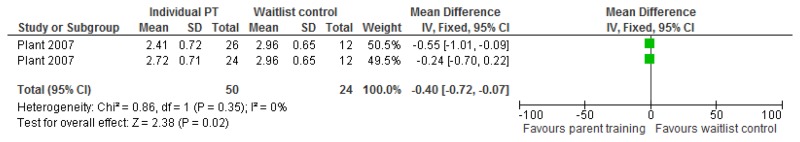

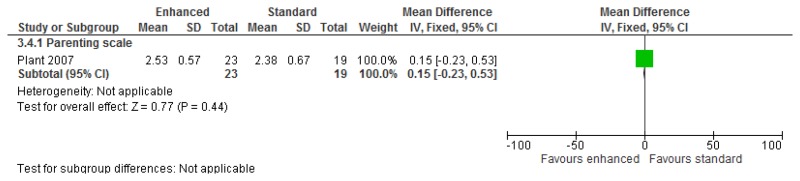

O.7. Interventions aimed at improving the health and well-being of carers of people with learning disabilities

Forest plots for carer outcomes from parent training are presented below. For all other forest plots relating to the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving the health and well-being of carers of people with learning disabilities please refer to the appropriate appendix in the challenging behaviour guideline.

![Click on image to zoom Figure 6. ROC curve for the PAS-ADD Checklist (psychiatric [unspecified] reference standard).](/books/NBK401813/bin/appof6.jpg)

![Click on image to zoom Figure 8. ROC curve for the Mini PAS-ADD (psychiatric diagnosis [unspecified] reference standard).](/books/NBK401813/bin/appof8.jpg)