Which serological assay to use

A systematic review (see Web annex 5.3) compared the diagnostic performance (sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values) of commercially available serological assays (RDTs and EIAs1) for the detection of HBsAg, when compared to a laboratory-based immunoassay reference standard (with or without a neutralization step). The review identified 30 studies (197–226) from 23 countries with varying prevalence of hepatitis B and evaluated 33 different RDTs. There were five studies of eight different EIAs against an immunoassay reference standard (214, 223, 227–229). A mixture of serum, plasma, capillary and venous whole blood specimens were used for RDTs, but only serum or plasma was used for EIAs. Seven studies assessed performance using capillary or venous whole blood (202, 206, 210, 215, 216, 218, 226). Sample size varied from 25 to 3928, and populations studied included healthy volunteers and blood donors, at-risk populations, pregnant women, incarcerated adults, and patients with confirmed hepatitis B.

RDTs. In 30 studies (197–226) of 33 different RDTs, the pooled clinical sensitivity of RDTs against different EIA reference standards was 90.0% (95% CI: 89.1–90.8) and pooled specificity was 99.5% (95% CI: 99.4–99.5) ().

Brands: there was significant variation in performance between RDT brands and within the same brand of RDT, with sensitivity ranging from 50% to 100% and specificity from 69% to 100%.

Specimen type: results for capillary whole blood specimens were comparable to serum but less heterogeneous.

EIAs. In five studies (214, 223, 227–229) of eight EIAs there was wide variation in EIA performance, with sensitivity ranging from 74% to 100% and specificity from 88% to 100%. The pooled sensitivity was 88.9% (95% CI: 87–90.6) and pooled specificity was 98.4% (95% CI: 97.8–98.8).

RDTs and EIAs in HIV-positive persons. Five studies (212, 214, 215, 218, 222) evaluated three different RDTs against different EIA reference standards. The pooled clinical sensitivity of RDTs was 72.3% (95% CI: 67.9–76.4), but specificity was 99.8% (95% CI: 99.5–99.9), compared to a pooled clinical sensitivity and specificity of 92.6% (95% CI: 89.8, 94.8) and 99.6% (95% CI: 99, 99.9), respectively, among HIV-negative persons. Possible explanations for this reduced sensitivity include an increased incidence of occult hepatitis B in HIV-positive persons (i.e. presence of HBV DNA with undetectable HBsAg levels, such that HBsAg might not be detected using the RDTs evaluated), and the use of tenofovir- or lamivudine-based antiretroviral regimens, which are active against HBV and may suppress HBV DNA and HBsAg levels. In the one study (214) that evaluated three EIAs against an EIA reference with neutralization, the overall pooled sensitivity in HIV-positive individuals was 97.9% (95% CI: 96.0–99.0) and specificity was 99.4% (95% CI: 99.0–99.7), suggesting that EIAs perform better in HIV-positive persons.

Analytical sensitivity/limit of detection. The analytical sensitivity or limit of detection (LoD) is another important performance criteria, but there were insufficient data in the included studies to undertake a systematic comparison. However, no RDTs met the levels of analytical sensitivity (i.e. LoD of 0.130 IU/mL) required by the European Union through its Common Technical Specifications. Data from WHO prequalification assessment studies indicate that the LoD of EIAs for HBsAg was 50–100-fold better compared to RDTs (230). However, despite this difference in analytical sensitivity, clinical sensitivity is unlikely to be greatly reduced because the vast majority of chronic HBV infection is associated with blood HBsAg concentrations well over 10 IU/mL. This is important, as it has been suggested that false-negative RDTs for HBsAg are due to low HBsAg viral load levels, the presence of HBsAg mutants or specific genotypes, and the use of lamivudine- or tenofovir-based ART regimens (208, 214, 216, 230).

The overall quality of the evidence for the recommendation of which serological assay to use was rated as low to moderate, with downgrading mainly due to serious risk of bias based on cross-sectional study design, and heterogeneity in results.

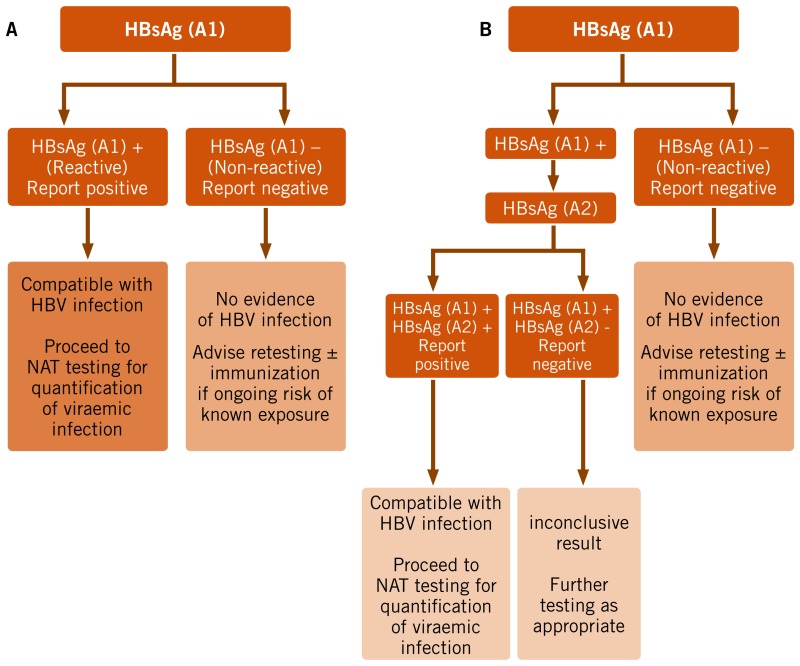

Which testing strategy to use

No studies were identified that directly compared the diagnostic accuracy of a one- versus two-assay serological testing strategy in high- and low-prevalence settings (see Web annex 5.5). A predictive modelling analysis was therefore undertaken, which examined diagnostic accuracy of a one- or two-assay strategy based on a hypothetical population of 1000 individuals across both a range of HBsAg seroprevalence levels (10%, 2%, 0.4% representing typical high-, medium- and low-seroprevalence settings or populations, respectively) and a range of assay performance characteristics (sensitivity of 98% and 90%, and specificity of 99% and 98% derived from the systematic review pooled sensitivity and specificity for HBsAg RDTs.

Prevalence had a strong impact on the PPV and the ratio of true-positive to false-positive results (see Web annex 6.1). The introduction of a second assay of similar sensitivity to be applied to all specimens reactive in the initial serological assay provides substantial potential gains in the PPV across all prevalence levels (>97%), but particularly at a low prevalence (0.4%) and with an assay that has a lower specificity.

The overall quality of the evidence for the recommendation on use of a one- or two-assay serological testing strategy was rated as low, as this was based on predictive modelling simulation and hypothetical scenarios.