The aim of this guideline is to improve the quality of essential intrapartum care with the ultimate goal of improving maternal, fetal and newborn outcomes. The recommended practices need to be deliverable within an appropriate model of care that can be adapted to different countries, local contexts and the individual woman. With the contributions of the members of the Guideline Development Group (GDG), WHO reviewed existing models of delivering intrapartum care with full consideration of the range of recommended practices within this guideline (Section 3) and through a human rights lens.

First, the GDG emphasized the urgent need to improve the quality of care around labour and childbirth in all settings. Acknowledging the substantial variations that exist in the philosophies driving the organization and provision of labour and childbirth care in contemporary practice, and the fact that clinical outcomes and experience of care for the woman and her baby are largely determined by the prevailing model of care, the GDG reviewed how intrapartum care for healthy pregnant women should be delivered in terms of cross-cutting clinical and non-clinical interventions that should be received by all women irrespective of context. To achieve the much-needed improvements to the quality of intrapartum care, the GDG recognized that a key shift is required in the practical ways that intrapartum care is delivered globally. This key shift is informed by the importance of achieving the best possible physical, emotional and psychological outcomes for the woman and her baby, irrespective of the influence of generic policies that may exist within and across health systems and countries. The group agreed that attainment of these outcomes requires a model of care in which health care providers give priority to the implementation of critical components that have been shown to be effective in improving both clinically relevant outcomes and childbirth experience for the woman and her family.

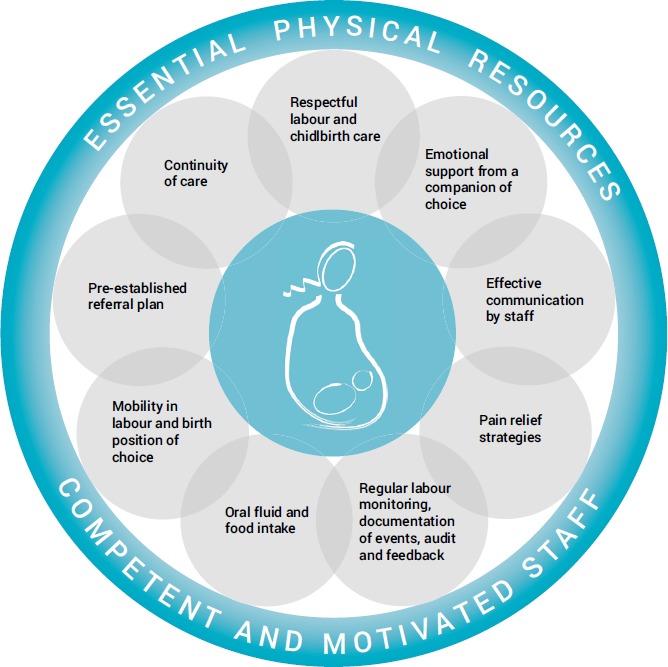

To this end, WHO proposes a global model of intrapartum care that subscribes to all domains of the WHO quality of care framework for maternal and newborn health (12) and places the woman and her baby at the centre of care provision (). It is based on the premise that care during labour can only be supportive of a woman's own capability to give birth without unnecessary interventions when synergistic evidence-based components are not fragmented but delivered together, giving her freedom to experience the birth of her baby, while at the same time ensuring timely and appropriate identification and management of complications if they arise. The model acknowledges the differences across settings in terms of existing models of care, and is flexible enough for adoption without disrupting the current organization of care.

The WHO intrapartum care model is founded on the 56 evidence-based recommendations included in this guideline. To optimize the potential of the new model and ensure that all women receive evidence-based, equitable and good-quality intrapartum care in health care facilities, these recommendations should be implemented as a package of care in all facility-based settings, by kind, competent and motivated health care professionals who have access to the essential physical resources. Health systems should aim to implement this model of care to empower all women to access the type of individualized care that they want and need, and to provide a sound foundation for such care, in accordance with a human rights-based approach. Implementation considerations for the WHO model can be found below in Box 4.1.

The WHO intrapartum care model has the potential to positively transform the lives of women, families and communities worldwide. It sets goals beyond the level of merely surviving, but at the level of thriving, in all country settings. The implementation of the WHO intrapartum care model should lead to cost savings through reductions in unnecessary medical interventions, with consequent improvements in equity for disadvantaged populations. Thus, addressing the shortage of skilled maternity care providers and improving the infrastructure required to successfully implement this model of evidence-based intrapartum care should be a top priority for all stakeholders.

BOX 4.1Considerations for the implementation of the WHO intrapartum care model

Health policy considerations

- ▪

A firm government commitment to increasing coverage of maternity care for all pregnant women giving birth in health care facilities is needed, irrespective of social, economic, ethnic, racial or other factors. National support must be secured for the whole package of recommendations, not just for specific components.

- ▪

To set the policy agenda, to secure broad anchoring and to ensure progress in policy formulation and decision-making, representatives of training facilities and professional societies should be included in participatory processes at all stages.

- ▪

To facilitate negotiations and planning, situation-specific information on the expected impact of the new intrapartum care model on service users, providers and costs should be compiled and disseminated.

- ▪

To be able to adequately ensure access for all women to quality maternity care, in the context of universal health coverage (UHC), strategies for raising public funding for health care will need revision. In low-income countries, donors could play a significant role in scaling up implementation.

Organizational or health-system-level considerations

- ▪

Long-term planning is needed for resource generation and budget allocation to address the shortage of skilled midwives, to improve facility infrastructure and referral pathways, and to strengthen and sustain good-quality maternity services.

- ▪

Introduction of the model should involve training institutions and professional bodies so that preservice and in-service training curricula can be updated as quickly and smoothly as possible.

- ▪

Standardized labour monitoring tools, including a revised partograph, will need to be developed to ensure that all health care providers (i) understand the key concepts around what constitutes normal and abnormal labour and labour progress, and the appropriate support required, and (ii) apply the standardized tools.

- ▪

The national Essential Medicines Lists will need to be updated (e.g. to include medicines to be available for pain relief during labour).

- ▪

Development or revision of national guidelines and/or facility-based protocols based on the WHO intrapartum care model is needed. For health care facilities without availability of caesarean section, context- or situation-specific guidance will need to be developed (e.g. taking into account travel time to the higher-level facility) to ensure timely and appropriate referral and transfer to a higher level of care if intrapartum complications develop.

- ▪

Good-quality supervision, communication and transport links between primary and higher-level facilities need to be established to ensure that referral pathways are efficient.

- ▪

Strategies will need to be devised to improve supply chain management according to local requirements, such as developing protocols for obtaining and maintaining stock of supplies.

- ▪

Consideration should be given to care provision at alternative maternity care facilities (e.g. on-site midwife-led birthing units) to facilitate the WHO intrapartum care model and reduce exposure of healthy pregnant women to unnecessary interventions prevalent in higher-level facilities.

- ▪

Behaviour change strategies aimed at health care providers and other stakeholders could be required in settings where non-evidence-based intrapartum care practices are entrenched.

- ▪

Successful implementation strategies should be documented and shared as examples of best practice for other implementers.

User-level considerations

- ▪

Community-level sensitization activities should be undertaken to disseminate information about:

- ▪

respectful maternity care (RMC) as a fundamental human right of pregnant women and babies in facilities;

- ▪

facility-based practices that lead to improvements in women's childbirth experience (e.g. RMC, labour and birth companionship, effective communication, choice of birth position, choice of pain relief method); and

- ▪

unnecessary birth practices that are not recommended for healthy pregnant women and that are no longer practised in facilities (e.g. liberal use of episiotomy, fundal pressure, routine amniotomy).