Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Patient Population. Adults with acute or chronic pain, including cancer patients, without progressive or terminal disease, treated in an outpatient setting, excluding hospice and end-of-life care.

Objectives. Provide a framework for comprehensive pain evaluation and individualized multimodal treatment. Improve quality of life and function in patients experiencing pain, while reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with pain treatments, particularly opioid analgesics.

Key Points

Acute Pain

Pain resolution. Acute pain is associated with tissue damage. As tissue heals, pain should resolve.

Limit opioid therapy. Avoid opioids for mild to moderate acute pain [IC]. Consider opioids for moderately-severe to severe acute or procedural pain [IIC], but if used, limit dose and duration. Do not prescribe opioids for sprains, lacerations, skin biopsies, or simple dental extractions [IIIE].

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain differs from acute pain. Chronic pain is not acute pain that failed to resolve. It is a distinct condition that is better understood as a disease process than as a symptom. Use a biopsychosocial approach in assessment and management.

Diagnosis

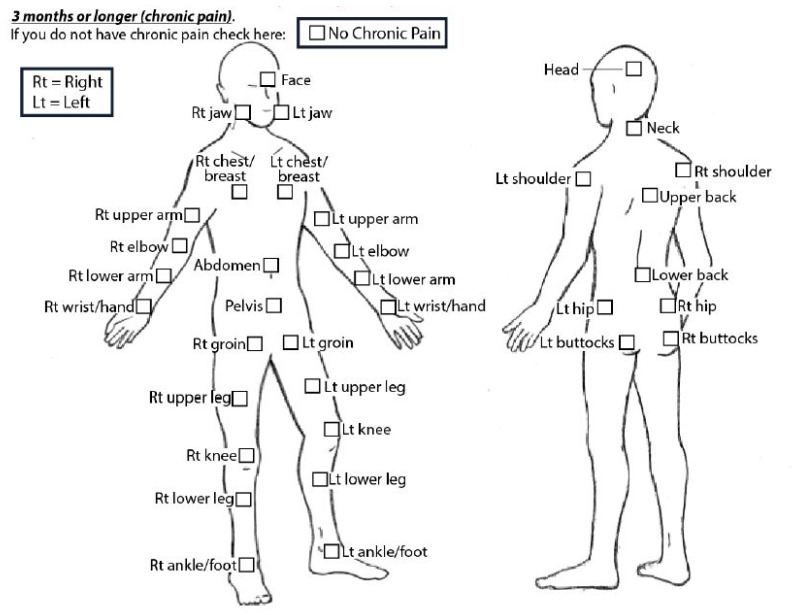

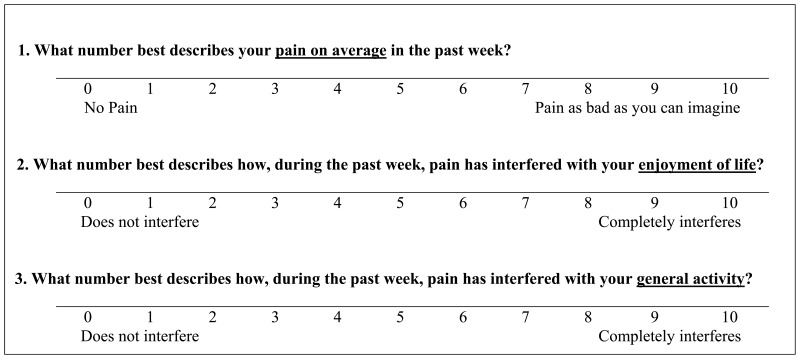

Chronic pain assessment. Perform a history and physical examination. Assess pain characteristics, pain treatment history, quality of life and functional impact, pain beliefs, and psychosocial factors. Assess comorbid conditions, including medical and psychiatric conditions, substance use, pain beliefs and expectations, and suicidality (Table 3) [IC]. Review any pertinent diagnostic studies [IC].

Table 3

Initial Evaluation of Chronic Pain.

Mechanism. Classify chronic pain as primary or secondary. Determine the underlying neurobiologic mechanism of pain: nociceptive, neuropathic, central (nociplastic). Assign the diagnosis of an underlying chronic pain syndrome, when applicable. (Table 2) [IC].

Table 2

Classification of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Relationship to Neurobiologic Mechanism of Pain.

Treatment

Create an individualized treatment plan (Table 4) utilizing multiple modalities, including non-pharmacologic (Tables 5-6) and non-opioid pharmacologic (Table 7) interventions [IC]. Use shared decision-making. Emphasize interventions with the lowest risk [IC].

Table 4

Creating an Individualized Pain Treatment Plan.

Table 5

Non-pharmacological Pain Treatment Options.

Table 6

Herbal Supplements Used in Chronic Pain.

Table 7

Non-Opioid Medications for Pain.

Assess response, address barriers to implementation and adjust the treatment plan [IC].

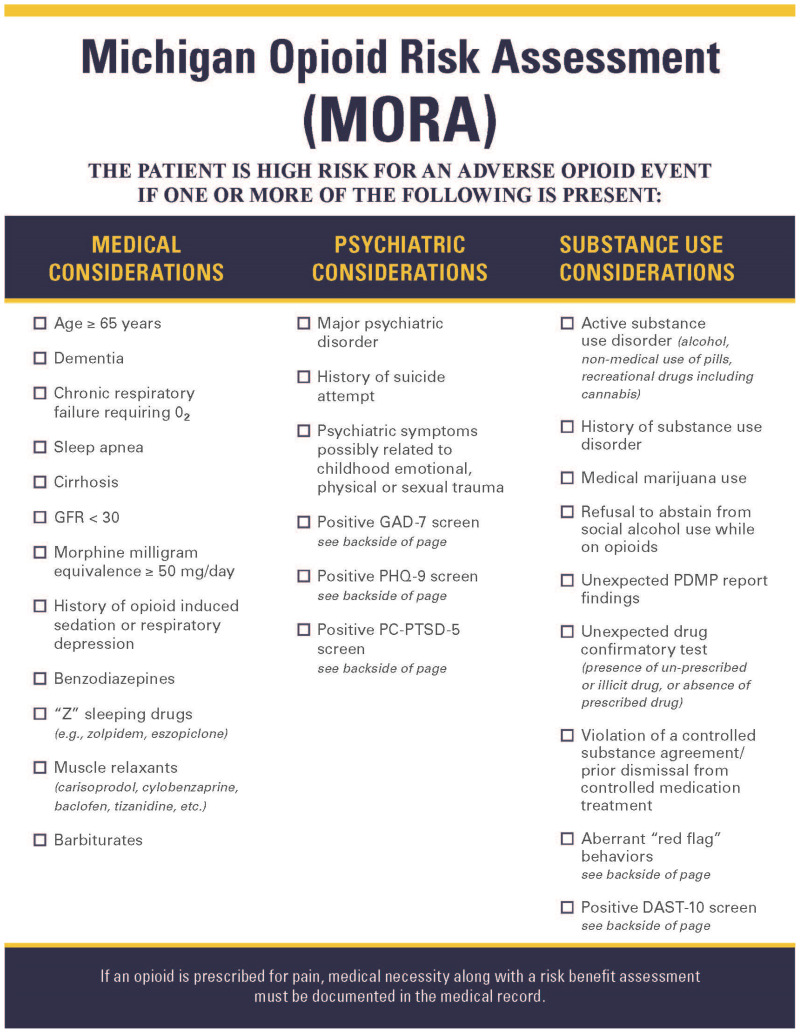

Generally, avoid opioid therapy. Opioids are not indicated for most patients with chronic pain (Figure 1) [IB]. If considering starting or continuing an opioid, thoroughly assess the risk of harm before proceeding [IB], and perform a full evaluation, including record review, urine comprehensive drug screen, and review of the state prescription drug monitoring program report (MAPS in Michigan). Potential benefits of opioid use must clearly outweigh risks [IE].

Figure 1

Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain in Opioid Naïve Patients (Not Including Active Cancer).

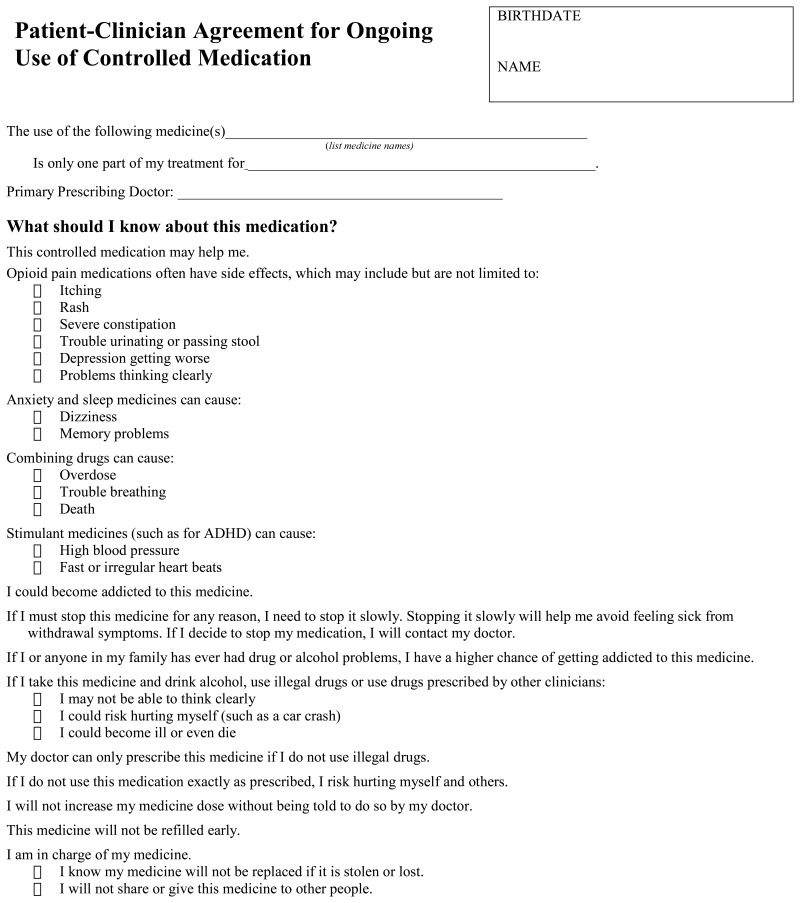

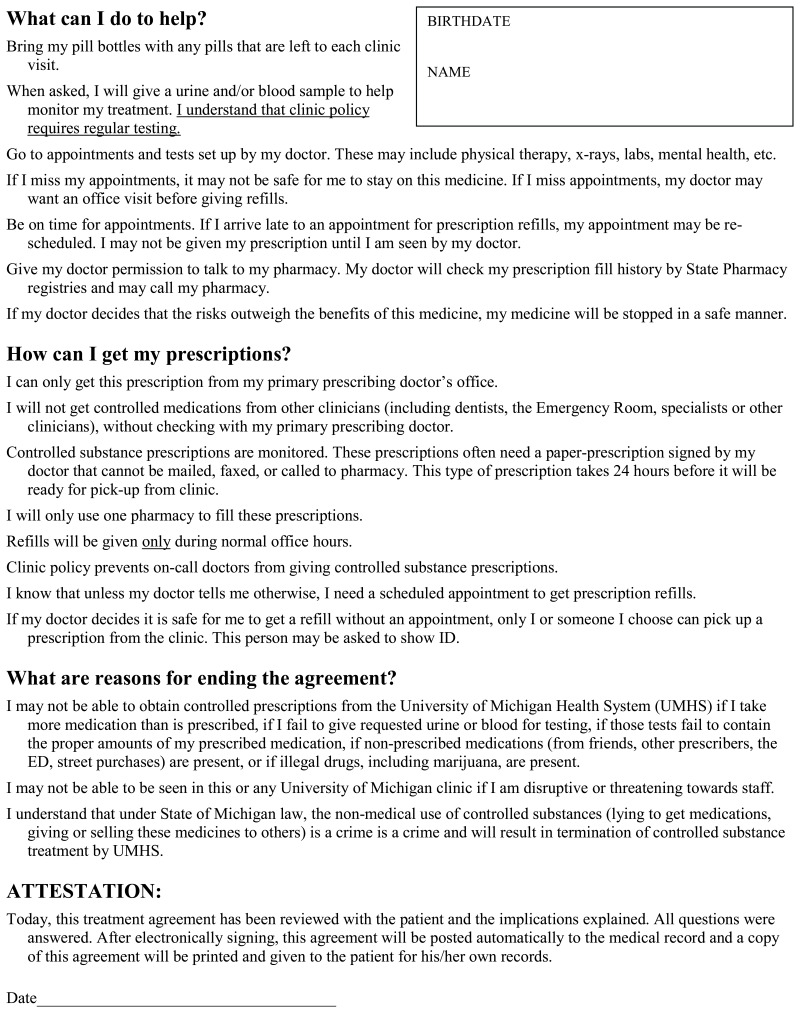

Obtain informed consent when prescribing opioids. Use the Start Talking Form and Controlled Substance Agreement. Provide opioid education. Discuss benefits and harms [IE].

Opioid Management (Figure 2)

Figure 2

Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain in Patients Already on Opioids (Not Including Active Cancer).

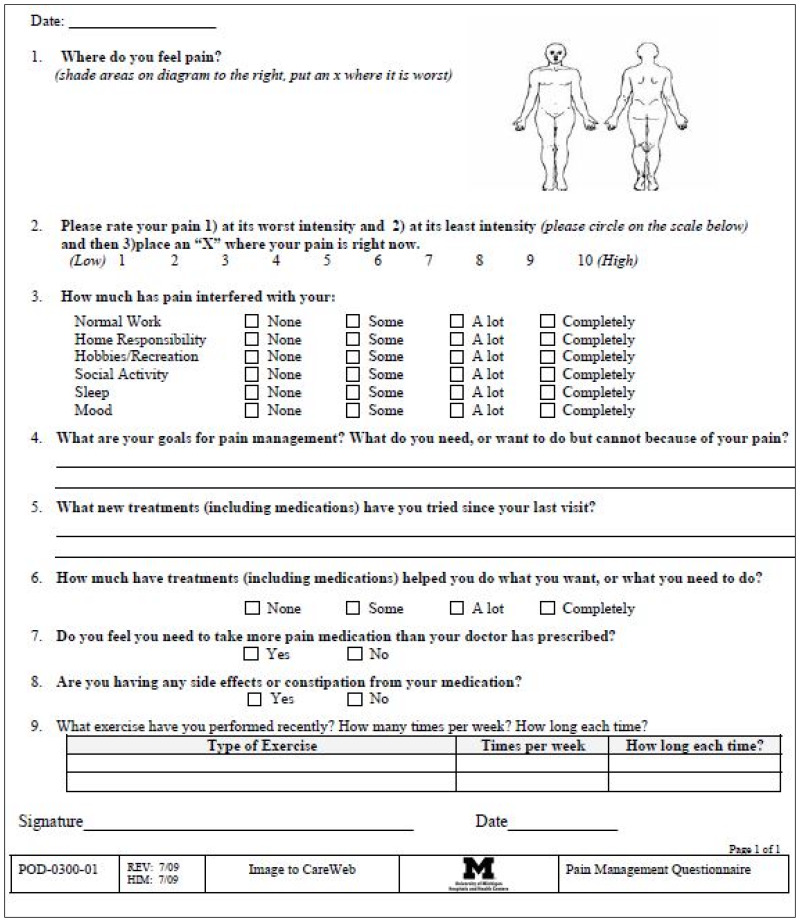

Regular visits/assess patients on chronic opioid therapy regularly, at least every 2-3 months (Table 9) [IE]. With each prescription, review benefits versus risks of therapy [IE]. Titrate (adjust) the dose to clinical effect and consider whether taper is indicated.

Table 9

Visit Checklist for Patients on Chronic Opioids.

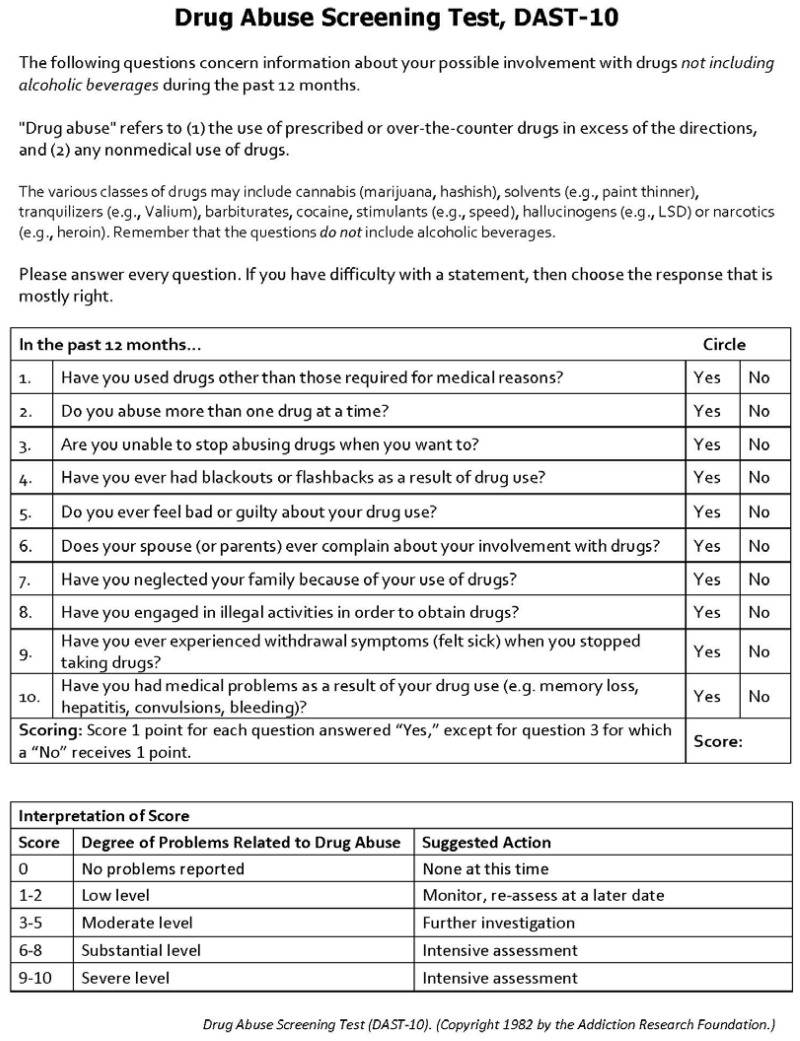

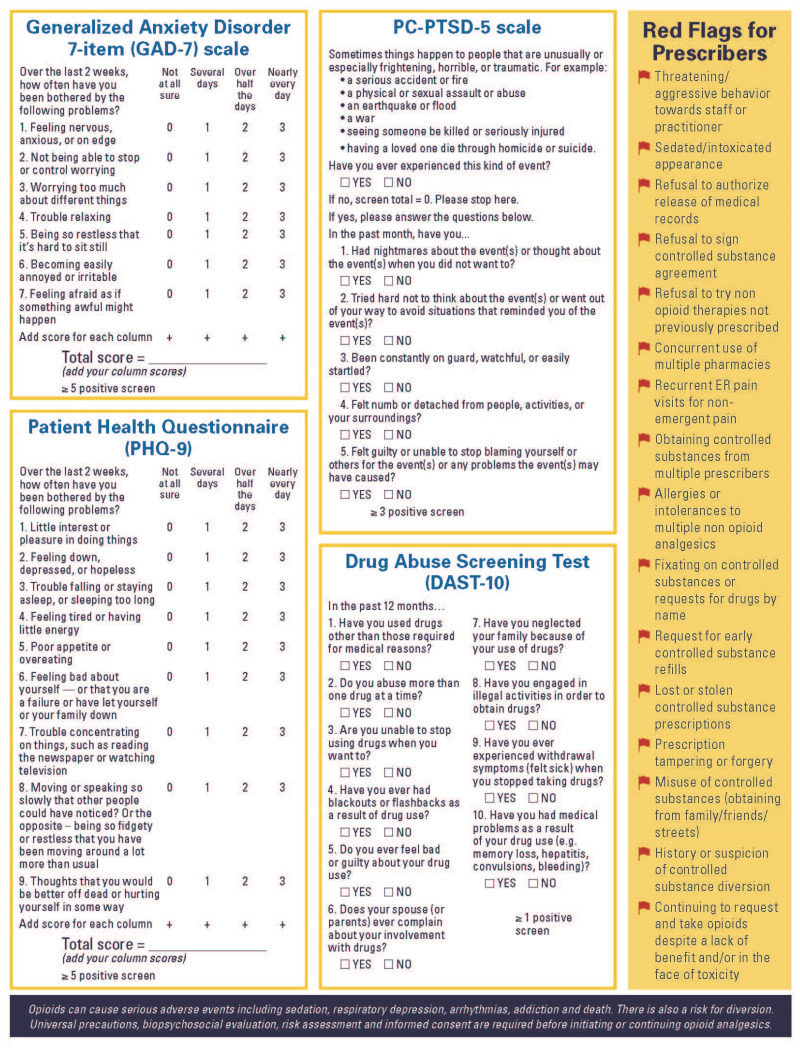

Monitor closely. Review the state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) report with each prescription [IE]. Calculate and monitor morphine milligram equivalents per day (MME/day) (Appendix C). Perform a urine drug screen at least once per year, and more often for patients who are at more than minimal risk [IE] (Appendix D). Watch for red flag behaviors (Table 10).

Table 10

Red Flag Behaviors That May Indicate Addiction or Diversion.

Indications for opioid discontinuation. If functional goals have not been met, adverse effects occur, or medication misuse is present (Table 10), consider opioid dose reduction, discontinuation, or conversion to buprenorphine [IIE]. In cases of opioid diversion, discontinue opioids [IE] and contact local law enforcement. In less urgent situations, discontinue using a rapid or slow taper [IE] (see Appendix F).

Screen for opioid use disorder. Assess for opioid use disorder, and consider complex persistent dependence [IE]. When present, refer to a specialist or offer treatment, including buprenorphine [IE].

Footnotes

- *

Strength of recommendation: I = generally perform; II = may be reasonable to perform; III = generally do not perform.

Level of evidence supporting a diagnostic method or an intervention: A = Systematic review of randomized controlled trials; B = randomized controlled trials; C = systematic review of nonrandomized controlled trials, nonrandomized controlled trials, group observation studies; D = Individual observation descriptive study; E = expert opinion.

Clinical Problem and Current Dilemma

Pain is often undertreated or incorrectly treated.

Chronic pain affects 50-80 million Americans.

Primary care clinicians manage the majority of patients with chronic pain.

The nationwide opioid epidemic adds complexity to the management of chronic pain.

Pain is the most common reason for which individuals seek health care. Effective pain management is a core responsibility of all clinicians, and is a growing priority among clinicians, patients, and regulators. Despite increased attention, many patients’ pain remains under-treated or incorrectly treated.

The prevalence of chronic pain in the US is difficult to estimate, but its impact is profound. Fifty to eighty million Americans experience daily pain symptoms. The cost of pain management is approximately $90 billion annually. Chronic pain is the leading cause of long-term disability in the US. These numbers will only increase as our population ages, amplifying the need for effective, accessible interventions to manage chronic pain and preserve function.

While multidisciplinary subspecialty pain services are increasingly available, primary care clinicians will continue to manage the majority of patients with chronic pain. This care can be challenging and resource-intensive, and many clinicians are reluctant or ill-equipped to provide it.

The current nation-wide opioid epidemic adds another layer of complexity in the management of chronic pain. Opioids carry substantial risk for harm, and are not recommended for the majority of patients with chronic pain. However, due to high rates of opioid prescribing over the last 20-30 years, there are still many patients who remain on chronic opioid therapy. With the widespread adoption of the CDC opioid-prescribing guidelines in 201611, rates of opioid prescriptions have decreased. In some cases, inflexible application of these guidelines has led to patient abandonment and poor outcomes. Prescribers need training, resources, and support to manage patients taking opioid medications in a compassionate and safe manner. There is also a need for better patient access to non-opioid pain management services and treatment for opioid use disorder.

This guideline is intended to support clinicians in evaluating and managing patients with pain and in navigating the complex issues involved with the use of opioids for pain management.

Acute and Subacute Pain – Overview

Definitions

Acute pain is associated with tissue damage and inflammation, with pain resolving as tissue heals.

Subacute pain, a subset of acute pain, may be present for 6 weeks to 3 months as tissue heals.

Chronic pain is a different medical condition involving abnormal peripheral or central neural function.

Acute pain is always associated with tissue damage; as tissue heals, pain should resolve. The definition of acute pain in the Michigan health code focuses on the cause and limited duration: “pain that is the normal, predicted physiological response to a noxious chemical, or a thermal or mechanical stimulus, and is typically associated with invasive procedures, trauma, and disease and usually lasts for a limited amount of time.” The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) further emphasizes the time limit for acute pain: it is pain lasting less than 3 months.

Subacute pain is a subset of acute pain: pain that has been present for at least 6 weeks but less than 3 months. This definition reflects the process of tissue healing. The worst of the acute pain phase and inflammation is no longer present, but ongoing tissue healing is required for full resolution.

Chronic pain has little in common with acute pain and should be considered as a separate medical condition. Some differences are:

| Acute Pain | Chronic Pain |

|---|---|

| Is a symptom | Is a diagnosis |

| Is associated with tissue damage | May or may not be associated with tissue damage |

| Lasts a limited time | Does not resolve quickly |

| May respond to opioid therapy for a limited time | Opioid therapy is generally not indicated |

| Has an inflammatory component | May or may not involve inflammation |

The differing pathophysiology for acute pain and chronic pain requires different approaches to their diagnosis and treatment. Effective acute pain management has been shown to improve both patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes, and reduce the risk of developing chronic pain.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Recommendations

Diagnose the cause of acute pain.

- Identify the medical or surgical condition for which acute pain is a symptom.

- Determine whether underlying cause is acute nociceptive pain or acute neuropathic pain.

- Assess the degree of functional impairment to help determine the urgency for addressing the acute pain issue.

Treating acute pain

- Consider the degree of tissue trauma, the patient’s situation, and unique patient factors.

- Select a treatment appropriate for the underlying source of pain (nociceptive or neuropathic).

- Adjust the treatment plan if reinjury or pain exacerbation occurs during the subacute phase.

Diagnosis. Identify the medical or surgical condition for which acute pain is a symptom (see Table 1). Often the cause is obvious or revealed by the history. If the diagnosis is not immediately clear, history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging may all be employed to arrive at the diagnosis.

Table 1

Acute Pain Overview by Severity and Cause.

Determine whether this is acute nociceptive pain (signaled to the brain via normally functioning afferent neural pathways) or acute neuropathic pain (dysfunctional neural functioning). Nociceptive and neuropathic pain are described in more detail below, under “General Approach to Chronic Pain”. This classification helps guide the treatment plan and medications to prescribe.

In some cases, the cause is not immediately obvious, but the category of pain is. For example, burning pain starting in the neck and radiating into the fingers could be associated with acute cervical radiculopathy or may evolve to reveal zoster. Both are types of acute neuropathic pain. Strategies would include reducing inflammation, quieting of nerves. and further diagnostic work up to determine the exact cause. Weakness may point towards radiculopathy, while the presence of a rash points towards zoster.

Assess the degree of functional impairment to help determine the urgency for addressing the acute pain issue. For example, weakness may require a more aggressive strategy with early intervention, such as advanced imaging. If a patient is no longer able to carry on a usual routine or activities of daily living due to acute pain, an aggressive diagnostic workup is needed. An aggressive workup is also required in patients with a history of malignancy or immunosuppression.

Treatment. In the treatment plan, address both the underlying cause and the associated acute pain. In developing a treatment plan for the acute pain, consider the degree of tissue trauma, the patient’s situation, and any unique patient factors. A patient in the immediate postoperative period after a major surgery will likely have more complex needs than a patient presenting for an ambulatory encounter.

The hallmark of acute pain is tissue inflammation. Acute pain can be nociceptive or neuropathic. Accordingly, measures to reduce inflammation are helpful when developing a treatment plan for acute pain conditions. Some treatments to consider for acute pain include those listed in the table below:

| Nociceptive | Neuropathic |

|---|---|

| NSAIDS Acetaminophen Steroids | Gabapentinoid anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin) |

| Topical anesthetics | |

| Duloxetine Nortriptyline/amitriptyline | |

| Nerve blocks | Nerve blocks |

| Ice, rest, elevation | Capsaicin |

| Distraction, TENS unit | TENS unit |

| Physical therapy, stretching | Desensitization therapy |

| Opioid based medications | |

Muscle relaxants

|

Plan for treatment of reinjury or exacerbation during the subacute pain phase. Often subacute pain occurs with increase in activity before tissue is completely restored to health. Have a plan to escalate analgesic needs for this well-defined occurrence. For example, anticipate how pain with physical therapy should be treated.

General Approach to Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is best understood as a disease process rather than a symptom.

Use a biopsychosocial approach when assessing and managing chronic pain.

Underlying mechanisms for chronic pain are:

- Nociceptive – tissue damage

- Neuropathic – sensory nervous system damage

- Central – heightened pain sensitivity in the central nervous system

Chronic pain has significant cognitive, affective, and interpersonal components.

Effective chronic pain management is focused on maximizing function and limiting disability, not just on reducing pain.

A chronic primary pain syndrome represents a disease that cannot be accounted for by another pain condition.

A chronic secondary pain syndrome initially manifests as a symptom of another disease and then continues after successful treatment of the disease.15

Biological and Psychosocial Factors

Chronic pain – pain that lasts or recurs for longer than 3 months – is not merely acute pain that does not resolve. Increasingly, chronic pain is recognized as a disease entity in and of itself, rather than as a symptom of another disease. Historically, pain has been viewed in a biomedical model, with a focus on identifying a specific pathologic cause of pain which can be treated through pharmacologic or interventional means. However, chronic pain is better understood by applying a biopsychosocial model. Chronic pain is a complex multi-dimensional condition, driven by the interplay of neurobiologic processes with psychosocial factors that may increase vulnerability or resilience to disease.16 A biopsychosocial approach allows the focus to move from the source of the pain to the management of its impact.

Neural mechanisms of Pain. Understanding the basic neurobiological mechanisms in chronic pain pathophysiology is important, since treatment approaches vary depending on these factors. There are three main subtypes of pain pathophysiology: nociceptive, neuropathic, and central sensitization. They are summarized below, with more detail regarding classification in Table 2.

Nociceptive pain is caused by tissue damage due to injury or inflammation, rather than harm to the central or peripheral nervous system. This is the primary type of pain involved in patients with arthritis, musculoskeletal inflammatory disorders (tendinosis, bursitis), or structural spine pain.

Neuropathic pain results from damage to the sensory nervous system. Patients typically describe electric, burning, or tingling sensations. Examples of neuropathic pain include post-herpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, and trigeminal neuralgia.

Central sensitization occurs when there is heightened pain sensitivity in the central nervous system that is not due to a peripheral pain signal generated by an injury or disease state. Central pain is driven by molecular and structural changes that occur in the central nervous system. It is the primary mechanism in conditions such as fibromyalgia, phantom limb syndrome, and chronic pelvic pain.

Psychosocial factors. Chronic pain has significant cognitive, affective and interpersonal components. Patients with chronic pain are more likely to report depression, anxiety, poor quality of life, and financial stress. They are five times more likely to use health care resources than patients without chronic pain. Pain beliefs and the individual and family response to chronic pain are also important factors.

Chronic Primary and Secondary Pain Syndromes

A classification system for chronic pain syndromes has been devised by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), as outlined in Table 2.

Chronic primary pain syndromes. These syndromes represent a disease itself. A chronic primary pain syndrome is defined as pain in one or more anatomical regions that persists or recurs for longer than 3 months and is associated with significant emotional distress or functional disability (interference with activities of daily life and participation in social roles) and that cannot be better accounted for by another chronic pain condition.17

Chronic primary pain syndromes include:

- Fibromyalgia

- Complex regional pain syndrome

- Chronic primary headache and orofacial pain

- Chronic primary visceral pain

- Chronic primary musculoskeletal pain

Chronic secondary pain syndromes

Each of these syndromes initially manifests as a symptom of another disease. After healing or successful treatment, chronic pain may sometimes continue and hence the chronic secondary pain diagnoses may remain and continue to guide treatment (Table 2).15

Chronic secondary pain syndromes include:

- Cancer-related pain (eg, from tumor mass or treatment)

- Chronic postsurgical or posttraumatic pain

- Chronic neuropathic pain

- Chronic secondary headache or orofacial pain

- Chronic secondary visceral pain

- Chronic secondary musculoskeletal pain

Establishing the diagnosis of a specific chronic pain syndrome can be an important first step in providing clarity for the care team, psychoeducation for patients, and direction for treatment considerations. In order to arrive at a diagnosis, perform a thorough biopsychosocial assessment.

Designing an Individualized Pain Treatment Plan

Recommendations

Use shared decision-making to develop an Individualized Pain Treatment Plan that promotes patient self-management.

Preferred therapy is non-pharmacologic or non-opioid pharmacologic and involves multiple modalities.

Avoid long-term opioid prescriptions for chronic pain. Opioids carry substantial risks of harm.

Identify and address clinician and health care system barriers to care.

Steps in creating an Individualized Pain Treatment Plan are outlined in Table 4.

Shared Decisions for Individualized Treatment

A trusting patient-clinician relationship is key to the development of an effective treatment plan for chronic pain. Construct a unique plan for each patient, taking into consideration the individual’s experience, circumstances, and preferences. The treatment plan should involve multimodal interventions, promote self-management, and enlist the involvement of a health care team. Use a shared decision-making approach, where patients and clinicians discuss values and preferences, review risks and benefits, and make a decision congruent with patient goals and preferences.29 Frequently reassess and adjust the plan to address barriers to care.

Key to developing an effective treatment plan is a supportive relationship with an empathetic clinician who acknowledges and empathizes with the patient’s experience. Set expectations regarding the available treatments for chronic pain. Establish realistic treatment goals for functional improvement or maintenance, not analgesia alone. Inform the patient that finding the right approach may take time.30 Facilitate patient self-management and provide pain psychoeducation (see Appendix H). A team-based approach is helpful in this effort, involving other clinical disciplines such as nursing or behavioral health consultants to provide coaching, education, and support.

A logical rationale for an intervention does not ensure the patient’s acceptance and participation in it. A patient’s acceptance of therapy is influenced by several complex factors, including characteristics of illness and identity. Patient preferences often favor physical rather than psychological intervention, but gains of psychological therapies may exceed patient expectations.31

Preferred Interventions

Non-pharmacologic therapy and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for the treatment of chronic pain.11 There is insufficient evidence to support the use of long-term opioid use for chronic pain. Opioids carry substantial risks of harm. Use shared decision-making to choose treatment interventions. A single intervention is unlikely to be fully effective for chronic pain, since chronic pain is a complex disease process with multiple contributing biopsychosocial factors. Combining several modalities, and emphasizing self-management is most effective.32 (Figure 1)

Clinician and Health Care System Barriers

When patients with chronic pain feel judged or scorned by health clinicians, this stigma can be a significant barrier to effective care. Similarly, clinicians caring for patients with chronic pain often experience negative emotions such as frustration, lack of appreciation, and guilt.30

Patients and clinicians alike encounter frustration when confronted with barriers within the health care system. Common barriers include difficulty in accessing care, limited time for visits, and inadequate reimbursement for evidence-based treatments.

A team-based approach, adequate consultative support, and training can begin to address some of these barriers. Patients may have individual barriers to accessing care or participating in self-management. Provide them with specific support as needed.

Assess cognitive and verbal ability

For patients with cognitive and/or verbal disability, when analgesic plan involves a caregiver, caregivers should receive additional education on pain assessment. Providers should also carefully assess function and goals with both patient and caregiver.

- Assess fall risk, cognition, respiratory status, and risk for sleep disordered breathing prior to prescribing opioids.

- Reduce the initial dose of opioids by 25-50% and titrate slowly to avoid over sedation.

- Consider using a non-verbal pain scale such as CPOT (Critical Care Pain Observation Tool) or FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) to assess efficacy of pain medications.

- Exercise universal precautions for controlled substance prescribing and limit pill count for patients at risk of having their medications diverted

- - Schedule frequent follow up with patients

- - Consider random urine drug screen (UDS)

- - Consider pill counts

- Emphasize the importance of keeping medications secure and locked to care provider/home manager.

- Provide disposal information for unused pills

- Ensure caregiver receives education on appropriate Intranasal Narcan use and administration to the patient if indicated

Health inequity and disparity

Many patient populations are unintentionally marginalized by both health care providers and health systems. This inequity is especially true with regard to pain management amongst non-white Hispanic, black, and other minority populations.33,34 Several factors should be considered when treating these vulnerable patients. It is the provider’s responsibility to recognize that inequity in this area is due in part, but not limited to, systemic barriers and complex influences such as implicit biases unbeknownst to providers. For example, patients with sickle cell disease frequently report difficulties in obtaining adequate pain relief from providers during a vaso-occlusive crisis. In this vulnerable population, studies have shown delays in administering pain medications due to accusations of drug seeking behavior, exaggeration of pain, and uninformed or negative attitudes held by providers concerning sickle cell disease.35

To diminish these inequities surrounding pain management, providers should attempt to remove as much individual discretion from decision making as feasible. When possible, providers should utilize resources such as: checklist, guidelines, or system protocols to avoid the influences of implicit biases on their management. Providers need also recognize access limitations faced by patients and ensure any treatment regimen or follow-up planning is readily accessible. An important consideration is to involve these patients in shared decision making while offering all available treatment options to circumvent and mitigate any healthcare related obstacles these patients may encounter. Alternative options should then be explored based on individual circumstances.

Non-Pharmacologic Treatment

Recommendations

Lifestyle management. For all patients, recommend:

- Regular exercise. Start small, gradually increase to at least 150 minutes/week at moderate intensity. Adjust this goal to the individual’s status.

- Teach good sleep habits. Screen for sleep disturbance. Consider sleep quality, post sleep evaluations, and sleep disordered breathing.

- A Mediterranean pattern of eating to lower inflammation and maintain a healthy weight.

Physical modalities:

- Consider physical therapy when patients have functional deficits or secondary pain generators.

- Consider massage therapy as part of a multimodal treatment plan.

Behavioral health interventions. Evidence-based interventions include mindfulness-based stress reduction, cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and self-regulatory and psychophysiological approaches (eg, biofeedback, relaxation training, hypnosis). See Appendix H.

- Refer patients with significant psychological issues (eg, comorbid psychiatric condition, previous trauma, challenges in managing and coping) to a psychologist or therapist.

- Consider referring any patient with chronic pain to a psychologist or therapist to address the psychological effects of chronic pain.

Integrative medicine:

- For interested patients, consider combining or coordinating historically non-mainstream practices that are evidence-based (eg, acupuncture, herbal supplements) as part of a multimodal treatment regimen.

- Evidence regarding the benefits and harms of marijuana for chronic pain is insufficient to recommend its use. Limited data support that using cannabidiol (CBD) alone is safe.

Non-pharmacologic options for treating chronic pain are summarized in Table 5.

Lifestyle Management

Exercise. For all patients recommend regular exercise as a component of multimodal treatment. Decrease the patients’ fear of movement. Encourage a progressive aerobic exercise program with a goal of at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise weekly. Adjust this goal for each individual’s physical status.

Exercise is structured, repetitive, physical activity to improve or maintain physical fitness. In patients with chronic pain, exercise improves both function and chronic pain symptoms, in addition to overall health and quality of life. Forms of exercise that have been studied include aerobic exercise, resistance-based exercise, water-based exercise, and styles of exercise such as yoga (for chronic primary musculoskeletal pain36), tai chi (for chronic primary musculoskeletal pain, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, neck pain37), and Pilates (for chronic primary musculoskeletal pain neck pain, osteoporosis38). Studies vary considerably in mode of exercise, content of program, frequency, and duration of activity. In most studies, the frequency of exercise was between 1–5 times per week, averaging 2–3 times a week. Another factor was whether activities were performed in supervised sessions or as home exercises, with home exercises potentially increasing the frequency of the activity. Prescribed exercise was generally moderate to moderately-high in intensity. No one type of exercise has been shown to be superior to another in all patient populations.

Sleep. For all patients recommend good sleep habits. Screen for sleep disturbance. Sleep complaints occur in 67–88% of individuals with chronic pain. Sleep and pain are often linked. Sleep disturbances may decrease pain thresholds and contribute to hypersensitivity of neural nociceptive pathways. Conversely, pain may disturb sleep. Nonpharmacologic sleep treatments are associated with improved fatigue and sleep quality. However, the effect on pain is comparatively modest and short-lived.

Diet. Recommend a Mediterranean pattern of eating to lower inflammation and maintain a healthy weight. Although inflammation is part of the nociceptive process, research into the role of diet in modifying inflammation is in its early stages. The Mediterranean pattern of eating, characterized by a high intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains and an emphasis on omega-3 fatty acids, has been established as a dietary pattern that lowers inflammation especially in the setting of cardiovascular disease.39 Emerging evidence shows connections between the Mediterranean pattern, lowered inflammation, and improvement in pain and function in osteoarthritis.40

Physical Modalities

Physical therapy. If patients have functional deficits or secondary pain generators that directed therapy may improve, refer them to physical therapy.

The goal of physical therapy is to improve function. Therapeutic exercise, other modalities, manual techniques, and patient education are part of a comprehensive treatment program to accomplish this goal.

- Modalities such as hot packs, ice, ultrasound, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), iontophoresis, and traction may decrease pain and increase tissue extensibility, thereby facilitating stretching and mobilization. Table 4 reviews selected modalities.

- Manual therapy helps optimize proper mobility, alignment and joint biomechanics.

- Therapeutic exercise consisting of stretching, strengthening, conditioning, and muscle re-education is useful in restoring joint range of motion, muscle strength, endurance, and to correct muscle imbalances.

Evidence is limited regarding the long-term benefit of any single individual treatment modality. However, they may be used as part of a multimodal treatment program to improve function, quality of life, and alleviate pain.

The basic components of a physical therapy prescription include:

- Diagnosis for which therapy is being prescribed.

- Therapeutic protocol for treatment, including therapeutic exercise, other modalities, and manual techniques to be employed or tried.

- Duration and frequency of desired therapy.

- Precautions.

When treatment goals have been met or when progress plateaus, formal therapy may be discontinued, but advise patients to continue with a program of independent daily home exercise.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Consider TENS either along with physical therapy or as an adjunct to multimodal treatment. TENS applies low voltage electrical stimulation using skin contact electrodes. Proposed mechanisms of action include gate control theory, endorphin theory, and augmentation of descending inhibition. Evidence is limited for the efficacy of TENS in pain management.41 However, it is relatively safe, with units relatively available and easy to use.

Do not use TENS near implanted or temporary stimulators (eg, pacemakers, intrathecal pumps, spinal cord stimulators), near sympathetic ganglia or the carotid sinus, near open incisions or abrasions, over thrombosis or thrombophlebitis, or in pregnancy. Use caution with patients with altered sensation, cognitive impairment, burns, malignancy, or open wounds.41

Massage therapy. Consider massage therapy as part of a multimodal treatment plan. Massage therapy is manual manipulation of muscles and connective tissue to enhance physical rehabilitation and improve relaxation. It can reduce pain scores for patients with low back pain,42 knee osteoarthritis,43 juvenile rheumatoid arthritis,43 chronic neck pain,43 and fibromyalgia.42 Not yet determined are the optimal number, duration and frequency of massage sessions for treating pain.

Behavioral Health Approaches

Refer patients with significant psychological issues (eg, comorbid psychiatric condition; previous physical, emotional, or sexual trauma; challenges in managing and coping) to a psychologist or therapist. Consider referring any patient with chronic pain to a psychologist or therapist to address the psychological effects of chronic pain. These interventions can be successful regardless of the patient’s baseline status.

Current psychological interventions for chronic pain are based on recent advances in our understanding of the complexity of pain perception. Pain is influenced by a wide range of psychosocial factors, such as emotions, sociocultural context, and pain-related beliefs, attitudes and expectations.

Chronic pain that persists for months or years often initiates a progressive loss of control over numerous aspects of one’s psychological and behavioral function. A biopsychosocial model is now the prevailing paradigm for interventional strategies designed to treat chronic pain. This model places an emphasis on addressing cognitive-behavioral factors pertinent to the patient’s pain experience.

The strong evidence for the contribution of psychosocial factors in pain experience, particularly in explaining disability attributed to pain, has led to the development of multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs (MPRPs) that simultaneously address physical, psychological, and functional aspects of chronic pain disorders. For some patients, referral for individual behavioral and psychological intervention may be all that is required.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The way patients think about themselves, others, and the future can have a major impact on their moods, behavior, and physiology. The two main tenants of CBT approaches to chronic pain are:

- The feeling of pain and the emotional, physical, and social impact of pain are interrelated, but can be separated for treatment purposes. Therefore, problems with functioning related to pain can be addressed even if pain is not targeted directly and remains unchanged.

- Psychological factors can influence the experience of pain itself.

Cognitive restructuring involves several steps that help to modify the way in which patients view pain and their ability to cope with pain. Treatment approaches that incorporate these principles can produce significant benefits, such as reduced pain, improved daily functioning, and improved quality of life.44–48

Mindfulness-based stress reduction. Mindfulness is a process of openly attending, with awareness, to one’s present moment experience.49 Mindfulness aims to empower patients to engage in active coping by encouraging them to be aware of the present, where difficult thoughts, feelings, and sensations are acknowledged and accepted without judgement.50

Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) may improve pain function in people with chronic pain. MBSR can provide patients with long-lasting skills effective for managing pain.34 Strong evidence shows that MBSR reduces functional disability and improves pain management for a variety of chronic pain conditions including low back pain,51 fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and patients with opioid misuse. The most studied intervention uses an 8-week format of 2-hour/week classes, a 6-hour day in the middle, and daily at-home audio recordings.

The mechanism of action for mindfulness-based strategies is unknown. It seems to be multifactorial, including both physical changes in the stress response system that drive markers of inflammation, as well as psychological mechanisms such as stress resilience and coping.52

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). ACT is a form of CBT. In some cases, trying to control or change pain and thoughts about pain can be counterproductive. ACT is an alternative way to increase acceptance of some of the aspects of chronic pain that may be difficult to alter. Acceptance may free individuals to pursue activities in line with their values.53 The ACT clinical model has six core processes:

- Acceptance of events and your feelings around them.

- Perceiving things as they are.

- Being present and mindful.

- Observing yourself in context.

- Identifying personal values.

- Setting goals based on your values and committing to actions in accordance with those goals.54

Various methods of delivering ACT have been shown to be effective in treating chronic pain55 either as an individual face-to-face intervention,56,57 a group-delivered face-to-face intervention,58–66 via self-help books,67,68 or through an internet-based delivery.69–73 ACT based therapy has been shown to decrease pain, improve function, and improve quality of life.

Self-regulatory and psychophysiological approaches. The experience of chronic pain elicits strong physiological reactions that are often accompanied by cognitive thoughts and processes. Several simple techniques harness the connection between the mind and body to improve awareness of and increase control over both psychological and physiological responses to pain.

Techniques include biofeedback, relaxation training, and hypnosis. Biofeedback provides real-time information about physiological processes (eg, heart rate, respiratory rate, muscle tension) with a goal of increasing voluntary control over them. It is often coupled with relaxation training (deep breathing or conscious focusing on relaxation). Biofeedback can decrease the frequency of pain, improve self-management, and decrease use of analgesic medications in both migraine and tension type headaches in adults and adolescents.74,75 Hypnosis is a state of increased attentional awareness leading to a state of increased relaxation. It has been examined in a variety of pain conditions and found to be effective in decreasing pain most pain conditions, with a reduction in overall pain between 29–45%.76,77 Effects of specific analgesic hypnotic suggestion were strongest in individuals of high to moderate suggestibility. Most people fall within those two categories, indicating a majority of people would benefit.76 A 2020 meta-analysis indicates a possible role for hypnosis in decreasing opioid medication, with hypnosis moderately reducing pain levels coupled with small reductions in opioid dosing.78

Integrative Medicine

For interested patients, consider adding historically non-mainstream practices that are evidence-based as part of a multimodal treatment regimen. As evidence emerges regarding the biological role of these treatments, their utility may change.

Integrative medicine is an approach that combines and coordinates conventional medicine with evidence-informed practices that historically are not mainstream. Emerging evidence suggests a role for many less conventional treatments in the management of chronic pain due to their benefits and safety compared to opioid therapy. In addition to previously noted treatments (massage, yoga, tai chi, mindfulness), accumulating evidence supports the use of acupuncture and herbal supplements. More information may be found at the Center for Complementary and Integrative Health at https://nccih.nih.gov/.

Acupuncture. Acupuncture in traditional Chinese medicine uses the insertion of needles into specific areas to manipulate anatomical energetic meridians. The nature of the psychological effect continues to be debated, but efficacy has been established for many chronic pain conditions.79 The best evidence exists for osteoarthritis, chronic neck and low back pain, fibromyalgia, and headache. Treatment frequency varies, with the most commonly cited being 1–2 times per week for 4–8 weeks. Some studies show effects lasting 6–12 months.80

Herbal supplements. Patients frequently request information about herbal supplements. The evidence for the use of some supplements is growing. Many are safe and may be considered when patients are interested. See Table 6.

Marijuana. Evidence regarding benefits and harms is currently insufficient to recommend using “medical” marijuana for chronic pain. Some data support cannabidiol (CBD) alone as being relatively safe.

With an increasing number of states legalizing marijuana, clinicians and patients are asking about the use of cannabinoids to treat a variety of conditions. The cannabis plant produces many phytocannabinoids, with the highest concentration of these being tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC is the molecule with psychoactive properties that appears to be responsible for most adverse effects. This remains a challenging and complex area to address. Regulatory and historical factors have resulted in very limited evidence concerning the endocannabinoid system and cannabis pharmacology.

Systematic reviews have found that cannabinoids may be modestly effective for some chronic pain, primarily neuropathic pain, based on limited evidence,43,44 However, the evidence is largely based on studies of high THC-containing products, which also show high rates of adverse events, such as sedation and psychomotor impairment. In the absence of regulation, the potency and composition of cannabis products are highly variable. Due to these factors, evidence is currently insufficient to recommend using marijuana for relief of chronic pain.

As new evidence begins to emerge regarding the possible role of CBD in analgesia and anti-inflammatory pathways, we may see a role for CBD alone or for products with a high CBD: THC ratio in chronic pain.81,82 For patients wishing to use CBD alone, some data support CBD as being relatively safe, although there are some potential cytochrome P450 metabolism interactions that should be reviewed. In 2018 the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reclassified the CBD-based product Epidiolex as Schedule V, which is the least restrictive schedule; however, it is only approved or studied in the setting of two forms of rare seizure disorder. CBD is not recommended for first-line therapy for the treatment of chronic pain. However, patients who have failed other treatments or are opioid dependent may be started on low (5–10 mg twice daily) doses, with slow increases of dose.81 Of note, these products are not regulated and therefore it is unclear how to determine dose or quality so these products should be considered with caution.

Non-Opioid Pharmacologic Treatment

Recommendations

Consider prescribing systemic or topical non-opioid medications as an adjunct to the non-pharmacologic treatments noted above. Medications often have limited effectiveness, significant interactions or toxicity, and may promote false beliefs about the benefit of medications.

Select medications based on:

- Known effectiveness for specific pain mechanisms (nociceptive, neuropathic, central sensitization)

- Potential to treat comorbid disorders, such as insomnia or mood disorder.

Prescribe an adequate trial of days to weeks of scheduled dosing. Avoid as-needed medication use.

Discontinue all ineffective medications to avoid polypharmacy, minimize toxicity, and limit unrealistic beliefs about the benefit of medications.

Several classes of medications can be part of effective chronic pain management, including acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), anticonvulsants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), muscle relaxants, and topical agents. Other non-opioid medications (eg, certain antidepressants and anticonvulsants) may simultaneously treat comorbid problems (eg, mood disorder, insomnia). Classes of non-opioid medications used for chronic pain and their potential benefits and harms are summarized in Table 7.

A successful regimen may combine low doses of different types of pain medications to treat different mechanisms of perceived pain simultaneously, increasing medication effectiveness while limiting the risk of toxicity.

- Primary pain syndromes such as chronic widespread pain (eg, fibromyalgia), headaches, and primary visceral pain (eg, irritable bowel syndrome) may respond to SNRIs, TCAs or anticonvulsants.

- Neuropathic pain may respond to those classes of medications as well as some topical agents.

- Nociceptive pain may respond to acetaminophen, NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, or topical agents.

- Neuropathic pain may respond to SNRIs, TCAs, anticonvulsants, or topical agents.

- Central pain syndromes such as chronic widespread pain (eg, fibromyalgia), headaches, and primary visceral pain (eg, irritable bowel syndrome) may respond to SNRIs, TCAs, or anticonvulsants.

Acetaminophen. Acetaminophen may occasionally be a useful medication to treat mild to moderate chronic pain, whether given as needed (“PRN” dosing), or at scheduled intervals. When combined, an NSAID and acetaminophen can be synergistic and equal to or more effective than acetaminophen plus an opioid.83

For healthy people, avoid total acetaminophen doses > 3 g/day (2 g/day in patients with chronic liver disease). Acetaminophen may cause small increases in the risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and small elevations of blood pressure.84

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs are among the most widely used medications in the US. Long-term NSAID therapy for chronic pain may benefit some patients, particularly those with defined pain generators and who are at low risk for complications. For low back pain, use of an oral NSAID is somewhat more effective than placebo for analgesia,85 but only slightly for disability. Celecoxib is more effective in low back pain than acetaminophen, but the effect is modest.86

Chronic NSAID use poses significant risks for gastrointestinal bleeding, acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease, and platelet dysfunction. Older age adds particular risk. Older adults receiving daily NSAIDs for six months or more face a 6-9% risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding requiring hospitalization. For high risk patients for whom NSAIDs have proved to be the only effective treatment, consider proton-pump inhibitors for upper gastrointestinal prophylaxis.

NSAIDs may also increase risk for exacerbations of hypertension, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. NSAID use in patients with heart disease or its risk factors increases the overall risk of heart attack or stroke.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

SNRIs (duloxetine, venlafaxine, or milnacipran) can benefit patients with a variety of pain syndromes, including non-specific low back pain, neuropathic pain of various origins, functional abdominal pain, and central pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. For low back pain, duloxetine at doses up to 120 mg/day reduced both non-specific and neuropathic symptoms. Its mechanism of action seems to be independent of any antidepressant effect. SNRIs are somewhat more effective for functional abdominal pain than tricyclics.87 Duloxetine is FDA-approved for diabetic neuropathy and fibromyalgia, though it improves pain scores more than function.

SNRIs are generally well-tolerated, but discontinuing an SNRI requires a gradual tapering down of the dose to avoid withdrawal symptoms, which can occasionally be severe.

Anticonvulsants. Anticonvulsant medications such as gabapentin, pregabalin, and topiramate can be effective for treating neuropathic pain. Dosing can be complex. They have significant adverse effects and are often only modestly effective. Additionally, use topiramate with caution in reproductive-aged women because it increases the risk of cleft lip and cleft palate in newborns.

Pregabalin is approved for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy and fibromyalgia, though it improves pain scores more than function. Gabapentin has only minor benefit in chronic daily headache or migraine. It is not effective in chronic non-specific low back pain.61,88 Gabapentin and pregabalin are not effective in acute low back pain.

Older anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine and phenytoin have some efficacy for neuropathic pain, but are associated with frequent adverse effects, drug-drug interactions and potentially severe adverse reactions, such as granulocytopenia and hyponatremia.

Pregabalin is a federal Schedule V controlled substance, and gabapentin has been scheduled in many states. Both of these medications produce an increased addiction risk. When combined with opioids, they have been associated with a small increase in death rate. Advise patients treated with gabapentin or pregabalin about increased appetite and the potential for rapid and marked weight gain.

Topiramate at higher doses has been associated with significant speech and cognitive effects

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). TCAs may be potentially useful in a variety of pain syndromes, particularly in neuropathic pain and headaches. They also may benefit comorbid disorders such as insomnia, anxiety, depression, panic disorder, and even smoking cessation efforts. TCAs may have particular use in neuropathic pain, vascular headache prophylaxis, and centralized pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. Trial data suggest only a modest benefit in functional abdominal pain and less benefit than SNRIs.89 In chronic low back pain, low dose TCAs resulted in somewhat less disability at 3 months but had less effect at 6 months.90

Doses required for pain treatment are lower than for mood disorders. The lower doses generally avoid problems such as QT prolongation. For patients with sleep initiation problems, taking a TCA at dinnertime rather than bedtime may reduce problems with sleep initiation and with morning fatigue.

When a TCA is used for pain or mood, the time needed for a response can be days to weeks.

TCAs may have adverse effects that can limit their usefulness, such as anticholinergic effects and dysrhythmias. Caution patients about enhanced appetite and the potential for weight gain. Constipation prophylaxis may be needed.

Muscle relaxants. Sedating or non-sedating muscle relaxants are often prescribed for chronic myofascial pain, despite little or no evidence for a long-term benefit.88 Cyclobenzaprine, tizanidine, and metaxalone can cause significant sedation, while methocarbamol is less likely to do so. Benzodiazepines pose a significant risk for long-term dependence and misuse, and they substantially increase the danger of overdose when used together with opioids. Baclofen, while somewhat useful for spasticity, has little role as a muscle relaxant, poses a significant risk for dependence, and should generally be avoided.

Topical agents. Topical NSAIDs and anesthetics are occasionally useful in nociceptive or neuropathic pain syndromes. They can be expensive and are often not covered by insurance.

- Topical lidocaine patches (prescribed or over-the-counter) can be effective. Ointment is less effective and can be messy. Both are expensive and often not covered by insurance. Over the counter 4% lidocaine cream is not expensive, but only marginally effective.

- Capsaicin cream (1%, not 0.25%) can be modestly effective, is available without prescription, but requires care in application to avoid unwanted burning. Compounded capsaicin 8% cream is more effective, but the cost may be prohibitive.

- When other treatments have failed, topical nitroglycerin may have some effect for wound pain, anal fissure pain, vulvodynia, and diabetic neuropathy.

- Compounded topical 5% morphine can provide local wound analgesia and may promote healing. It is only available at compounding pharmacies and can be expensive.

Systemic effects of topical agents are generally minimal. Headache can complicate treatment with nitroglycerin. Avoid nitroglycerin in patients who use phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (avanafil, sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil) for erectile dysfunction.

Opioids: Decision Phase

Recommendations

Assess factors that indicate whether opioids may be beneficial.

Consider potential risks of opioids:

- Potential risks of opioid use for all patients include: physical adverse effects; cognitive impairment; social, personal, and family risks; failing urine screening; potential for opioid misuse.

- Special populations – Patients with factors such as older age, pregnancy, lactation, or chronic illness have higher risks associated with opioid use (Table 8).

- Benzodiazepines – Generally do not initiate opioid therapy in patients routinely using benzodiazepine therapy. Both increase sedation and suppress breathing.

- Marijuana – Discourage concomitant use of THC- containing marijuana products and opioids. Marijuana’s adverse effects may compound those of opioids.

Assess the benefits and risks to determine whether an opioid will improve overall chronic pain management.

Decide whether to recommend adding an opioid to treatment.

Considerations for Opioid Use

Deciding whether to prescribe opioids is based on an assessment of benefits and harms. While opioids should never be the main treatment for chronic (or acute) pain, in some circumstances, opioids may complement other therapeutic efforts. Important considerations and branching decisions are illustrated in Figure 1 for opioid naïve patients and Figure 2 for patients already on opioids.

Potential Benefit

Assess factors that indicate whether opioids may be beneficial. Based on pain assessment, characterize the patient’s pain based on:

- Time frame: acute, subacute, or chronic.

- Mechanism: nociceptive, neuropathic, central, or a combination of these. Many pain states are the result of a “mixed picture.”

- Pain generators: list each painful area and determine each pain generator.

- Approximate percentage: establish the percentage of pain each pain generator is contributing to the overall clinical status.

A careful history can indicate the types of pain involved and guide treatment plans. For example, if NSAIDs provide significant relief, an inflammatory component to pain is likely. Note whether other modalities and medications have helped or not, and incorporate that information into the treatment plan. Use past experience to guide the decision to start membrane stabilizers (anticonvulsants) and other non-opioid therapies and to determine initial doses. As with all medical decisions, carefully consider risks and benefits.

Short-term opioid therapy may be appropriate for acute pain management to allow for rehabilitation. For chronic pain, opioid therapy is beneficial if it allows a return to function or maintenance of function with minimal adverse effects. If patients are not meeting functional goals during the course of therapy for nonmalignant pain, opioid therapy has failed and should be discontinued.

Potential Risks

Review the patient’s risks and determine if opioid-based therapy is likely to result in harm.

General risks. Potential risks for all patients include:

- Physical adverse effects. Common opioid adverse effects include nausea, constipation, pruritus, respiratory depression, and hot flashes. Chronic opioid use can alter endocrine function and may also lead to dry mouth and subsequent dental caries.

- Cognitive impairment. Patients new to opioids should not drive a vehicle or operate power equipment or heavy machinery until they see how they are impacted by the therapy.

- Social, personal, and family risks. Being an opioid user carries a risk for social stigma. Additional risks are inherent to possessing opioids, including becoming a target for home invasion. Insecure storage may put other family members and pets at risk for opioid poisoning.

- Failing urine drug screening tests. Some jobs require a negative urine drug screen, and employment may not be compatible with opioid therapy. Patient can be harmed financially and professionally if they screen positive for an opioid, even when prescribed and monitored by a clinician.

- Potential for opioid misuse or opioid use disorder.

- - Patients with depression, anxiety, or a history of substance use disorder are at risk.

- - Patients with active alcohol use disorder, illicit drug use, or a history of these problems are at risk.

Special populations. Older age, pregnancy, lactation, and chronic illness can impact the safety of opioid medications, so use extra caution with these patient populations. Specific considerations are outlined in Table 8.

Table 8

Special Populations for Whom Opioids Increase Risks. Risks of opioid therapy are higher in these populations. Non-pharmacologic and non-opioid pharmacologic therapies are preferred.

Benzodiazepine and opioids – a safety concern. Generally, do not initiate opioid therapy in patients routinely using benzodiazepine therapy. Both drugs are sedating and suppress breathing. Together they can cause a fatal overdose.

In select cases, co-prescribing may be warranted, such as use of a benzodiazepine for an MRI. In those cases, discuss the risks with the patient. Furthermore, consider the kinetics of each drug relative to the timing of procedures. For example, counsel patients taking hydrocodone daily to skip a dose if they need to take a benzodiazepine for an MRI; benzodiazepines and short-acting opioids should not be taken within two hours of each other. When clinicians inherit patients who are co-prescribed sedatives and opioids, carefully review the relative benefit of each medication and prescribe intranasal naloxone. Consider discontinuing one of the medications.

Marijuana, CBD, and opioids. Discourage concomitant use of THC-containing marijuana products and opioids. The adverse effects of cannabis products may compound similar effects with opioids, leading to safety concerns. Evidence about the combined use of cannabis and opioid prescriptions is limited and inconclusive at present.94 If opioids are otherwise indicated, current evidence is insufficient to recommend against prescribing opioids to patients using CBD alone.

Opioid Risk/Benefit Decision

As with all medications, consider the risks and benefits of prescribing an opioid.

Expected functional benefits of opioid use should be clear, with the continuation of opioid therapy dependent on achieving them. While improved sleep and mood are somewhat subjective and should be noted, seek more objective evidence of benefit in order to prescribe and continue opioid therapy. Consider the ability to walk farther, exercise longer, work more, etc. Before initiating opioid therapy, ask patients to identify the functional goals they wish to achieve with opioid therapy, then see if they are meeting these goals at follow up.

Occasionally opioids may have less risk than other pain management medications. Examples include patients vulnerable to gastrointestinal bleeding for whom NSAIDs are contraindicated and patients experiencing cognitive effects from membrane stabilizers.

Opioids: Initiation and Treatment Phase

An overview of prescribing opioids in opioid naïve patients is presented in Figure 1.

Drug Selection and Dosing

Recommendations

In selecting opioids, consider patient factors:

- History with opioids: opioid naïve or opioid tolerant

- Previous opioids used

- Special population factors (eg, older age, pregnancy); see Table 8

- Need for accompanying naloxone prescription.

Dosing:

- For initial daily doses, start with a short-acting opioid, and do not exceed 20 MME/day (oral morphine milligram equivalents per day).

- For up titration over time, do not exceed 50 MME/day.

Assess initial responses frequently. See the patient every 1-4 weeks. Titrate the dose and assess response within 2-6 weeks.

When the benefits of adding an opioid to other therapy outweigh the risks, select the initial drug and dose based on the:

- Patient:

- - Opioid naïve or opioid tolerant (ie, has been on ≥ 60 MME/day or 25 mcg/hour transdermal fentanyl for ≥ 7 days)

- - Patients previously treated with opioids

- - Special populations affecting dosing

- Drug:

- - Duration

- - Potency

- - Delivery mechanism

All opioids are essentially similar regarding effects and adverse effects. True allergy to any of them is very rare. Morphine and codeine may be slightly less well tolerated, but can be used unless adverse effects become intolerable or a medical contraindication is present.

Opioid naïve patients. In these patients, start with a short-acting opioid at a dose of ≤ 20 MME/day. Over time, the dose may be cautiously titrated. Do not exceed a daily dose of 50 MME.

Opioid tolerant patients. Morphine is the default choice, unless contraindicated. Morphine can be prescribed by all routes, unlike oxycodone. It has a straightforward dose calculation with a predictable analgesic interchange and conversion between parenteral and oral dosing. It is available in long-acting preparations. Cost of all forms of oral morphine is lower, and the long-acting form is covered by all insurances, including Medicaid. The maximum daily dose should not exceed 50 MME. For any doses > 90 MME/day, document the medical justification.

Another option for opioid tolerant patients is buprenorphine, transdermal or buccal. Compared to full agonist therapy, buprenorphine has no ceiling on respiratory depression, generally provides good analgesia, gives consistent serum plasma levels, and does not lead to hyperalgesia or tolerance with the same frequency. Transdermal buprenorphine dosed at 5 mcg/hr (one patch per week) is approximately equal to 20 MME/day. Starting doses of buccal buprenorphine would be 75 mcg once or twice/day. Unfortunately, these options may not be covered by some insurances such as Medicaid.

Transdermal buprenorphine takes approximately 12-24 hours to reach a steady state, during which a short-acting oral opioid may be needed for one-half to a full day, and then should be discontinued. Advise patients to rotate patch locations to avoid skin breakdown. If a rash occurs due to contact with the adhesive, minimize this problem by applying a medium-strength topical steroid such as 0.1% triamcinolone cream to the area 2 hours prior to placement of the patch.

Previous opioids used. If a patient is on multiple opioids, convert to a single opioid when possible. For patients treated with short-acting medications, convert to or add a long-acting medication using the equianalgesic dosing (MME/day) and conversion information in Appendix C. Once the patient is on a long-acting opioid, the short-acting opioid should generally be discontinued.

Dosing for special populations. Older age, pregnancy, lactation, and chronic illness impact the safety of opioid medications, opioid choice, and dosing. Specific considerations are outlined in Table 8.

Naloxone indications. Patients with medical conditions impacting the heart, lungs, or central nervous system are candidates for intranasal naloxone as a rescue strategy. Any patient, regardless of medical comorbidity, who is on > 50 MME/day should also have intranasal naloxone prescribed. Educate family and friends on how and under what circumstances to administer the intranasal naloxone. If a patient is taking benzodiazepines or uses other sedating medications, discuss the risks, prescribe intranasal naloxone, and consider tapering down the opioid dose or converting to an alternative analgesic strategy.

Drug duration and conversion to long-acting preparations. Limit short-acting opioid use over time. If pain persists beyond a few weeks and opioid use is thought to be beneficial, or requiring continuation of greater than 20-30 MME/day, consider converting to a long-acting preparation. Long-acting preparations provide more stable serum levels and slow the development of opioid tolerance. Short-acting opioids used over time result in tolerance more rapidly than long-acting opioids.

Breakthrough Pain. During dose titration, short-acting medication may be provided for breakthrough pain, but should soon be discontinued. In general, when long-acting opioid preparations are prescribed, use of a short-acting opioid should be a few times per month or not at all. Breakthrough dosing should not occur in multiple daily doses. The only exception is during the first few days of titration, when the long-acting medication is being adjusted to a proper steady state dose. This generally takes 3-5 half-lives of the medication.

Frequent initial assessments. Initially see the patient frequently (every 1-4 weeks) to assess their response to the opioid treatment, monitor for adverse effects, assure compliance, and assess for any inappropriate use or behavior. Reminders of the terms of the treatment agreement are useful in this stage.

Reassess the plan in as soon as 2-6 weeks. Keep the dose titration phase relatively short. If after 2-6 weeks, the patient has not achieved satisfactory pain control with a stable dose of medication, refer the patient to a pain management specialist. It is also reasonable to consider discontinuation of opioids at this point, assuming that adequate dosing was given. Opioids do not effectively treat all patients.

Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Fentanyl

Recommendations

Methadone

- Only clinicians with experience with methadone should prescribe it.

- Do not use methadone as first-line treatment for chronic pain.

- Consider methadone for its prolonged duration of effect, which is useful for longer term therapy and minimizes euphoria with low doses.

- Avoid prescribing methadone in combination with other controlled substances.

Buprenorphine

- Consider buprenorphine when a safer, lower side-effect profile medication is preferred over full agonist opioids or for patients with tolerance to other opioids.

- Consider its higher expense.

- Be familiar with transdermal and buccal buprenorphine. Sublingual buprenorphine should be initiated only by prescribers trained in its use. It can provoke acute opioid withdrawal if not done correctly.

- Buprenorphine can be prescribed for pain without an XDEA waiver, but the waiver is required to prescribe medication-assisted therapy for opioid use disorder.

Fentanyl

- Do NOT consider fentanyl for opioid naïve patients.

- Consider prescribing fentanyl in only a few unusual situations (see text).

- Do NOT use transdermal fentanyl over a long period because opioid tolerance develops quickly.

These three drugs have special properties and uses deserving special description.

Methadone. Do not use methadone as first-line treatment for chronic pain. Before a clinician prescribes methadone, the clinician should have gained experience monitoring and prescribing it, or should consult a pain specialist.

Special safety hazard and unique advantages. Methadone is unique among opioids, with both increased safety concerns and advantages in long-term therapy. The safe use of methadone requires knowledge of its particular pharmacologic properties. Methadone’s duration of adverse effects far exceeds its analgesic half-life, making it dangerous when combined inappropriately with other controlled substances. Methadone may be useful for patients who require prolonged opioid therapy because it does not tend to require increasingly large doses over time (tolerance). Methadone is also available at relatively low cost.

Many patients are aware that methadone is often associated with opioid addiction therapy. Patients may need additional counseling that methadone is an effective analgesic, not merely a treatment for opioid addiction.

Longer duration affects dose titration. Methadone has a prolonged terminal half-life, so the degree of potential adverse effects can increase over several days after an initial dose or a change of dosage. The duration of methadone analgesia upon initiation may be only 6-8 hours. However, with repeated use, daily to three times daily dosing is effective.

Be cautious when converting from another opioid to methadone (Appendix C).95,96 As the MME/day rises, the methadone/morphine conversion ratio declines until methadone is approximately twenty times as potent as oral morphine (daily doses of morphine above 500 mg). Refer patients requiring high dose conversions to or from methadone to a specialist in pain management who has experience with methadone dosing.

During the first few days of methadone use, supplemental short-acting opioids may be used to manage inadequate analgesia, then discontinued. Educate the patient about the delayed response of both therapeutic and adverse effects for methadone. For this reason, avoid prescribing benzodiazepines or other sedatives along with methadone. For opioid-naïve patients, initiate methadone at very low doses (< 10 mg/day) divided into twice daily or three times daily dosing. For opioid-tolerant patients, initiate methadone using proper rotation ratios (Appendix C). Starting doses of methadone should not exceed 30 mg/day, even in opioid tolerant patients. Higher dose conversions may be indicated for some patients, but should prompt consultation with a pain management specialist. Regardless of starting dose, titrate (adjust) methadone doses in small increments (max 10-15% of total daily dose) not more often than once every 7 days. Typical methadone dosing for pain is in the range of 5-30 mg/day in divided doses. Higher doses enter the range of opioid addiction treatment.

Effect on QT interval. Methadone can prolong QT interval, especially at higher doses (≥ 100 mg/day) or when used in combination with other medications that prolong QT, including several classes of common antibiotics (eg, macrolides and quinolones). Perform periodic EKG monitoring for patients on higher doses of methadone, and for those being considered for methadone therapy if they are using other QT-prolonging medications (list available at www.qtdrugs.org).

Methadone testing. Methadone, like other opioid analgesics, is associated with a substantial risk for diversion. Mere confirmation of its presence on GC/MS, LC/MS or specific EIA testing (the “opioid” screening test misses methadone) may not be adequate. Prescribers should have a low threshold for periodic testing of serum levels. Specimens should be drawn knowing the variables of patient weight (kg), time since last dose taken (hours), and the total daily methadone dose (mg). Also, be aware of drug interactions that may affect an individual’s methadone clearance. To estimate the expected serum trough level in ng/mL: 263 x total daily dose divided by the patient’s weight. Methadone serum level peaks approximately two hours after dosing and fades over 5-6 hours. A peak level would be approximately double a trough level.

Buprenorphine. Buprenorphine is a partial agonist opioid that is potent and long-acting. Consider prescribing it when a safer, lower adverse effect profile is preferred over full agonist opioids, or for patients who have developed tolerance to other opioids.

Advantages of buprenorphine include its effectiveness, and lack of development of tolerance to it. As a Schedule III drug, it may be written with refills for up to 6 months. Disadvantages include occasional problems with rash from transdermal patch use, and greater expense.

Transdermal buprenorphine (Butrans and generic) is FDA-approved for treating pain. It does not require an XDEA number or training to prescribe. The transdermal form is a good alternative for patients who have developed tolerance to other opioids, had a benefit from opioid treatment but wish to escalate treatment, and are taking ≤ 80 MME/day. Start with a 5 or 10 mcg patch (changed weekly), and discontinue other opioids.

Buccal buprenorphine (Belbuca) is also FDA-approved for pain treatment. It is given twice daily in patients who have previously been treated with opioid up to 160 MME/day. As with transdermal buprenorphine, it is effective, its misuse risk is low and its pharmacokinetics are not complicated. Cost can be a limiting factor.

Sublingual buprenorphine (Suboxone, Subutex and generic) may be prescribed off-label for pain with a regular DEA number. Sublingual buprenorphine has an evolving role, particularly in patients already treated with high dose opioid therapy who continue to complain of uncontrolled pain, and who may or may not have opioid use disorder. It offers a safer, effective option to full agonist opioids, has a lower risk for misuse, produces less opioid tolerance, causes fewer adverse effects, and can enhance mood. Unfortunately, its higher cost and lack of clinician knowledge of its proper use have so far limited its use as a pain treatment.

Initiation of sublingual buprenorphine can provoke acute opioid withdrawal if not done correctly. Therefore, only prescribers trained in its use and in possession of an XDEA number (or working under guidance of such a prescriber) should initiate sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone. Once a patient is on it and stable, primary prescribers may take over chronic management.

Fentanyl. Do not prescribe fentanyl for opioid naïve patients. Only consider prescribing fentanyl in a few unusual situations. Possible examples include: transdermal when gut mu receptors should be avoided; in head and neck cancer when oral intake is challenging; end of life care; intravenous in a patient with intrathecal “pain pump”; buccal and sublingual for episodic and breakthrough end-stage cancer pain.

Transdermal fentanyl (Duragesic and generic) has limited use for treatment of chronic pain. Transdermal fentanyl is a short-acting opioid packaged in a long-acting delivery system, making patients on it especially prone to development of opioid tolerance.

Transdermal fentanyl has a black box warning for opioid naïve patients. It should only be considered, even at low doses, for patients who are tolerant to opioids. Plasma levels of transdermal fentanyl are erratic and are influenced by several factors, including patient temperature, ambient humidity and temperature, skin thickness, presence of adipose tissue, and location of patch. The patch should never be placed on an open wound or mucous membrane. An expired transdermal patch still has a significant amount of fentanyl in it and must be discarded properly.

Dosing of transdermal fentanyl can be complicated; however, a general rule is that the dose of the patch in micrograms x 2 is roughly equivalent to the oral MME/day. For example, a patient on a 50 mcg/hr patch (with a new patch every 3 days) is receiving approximately 100 MME/day (50 x 2 = 100), and a patient on a 100 mcg/hr patch is receiving approximately 200 MME/day, etc. Transdermal fentanyl is commonly available in 12, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mcg/hr patches.

Buccal and lozenge fentanyl. Fentanyl “lollipops” (Actiq) are rapid-acting forms of fentanyl indicated for episodic and breakthrough end-stage cancer pain and generally, should not be prescribed. There is a black box warning on this formulation for using it only in opioid tolerant patients with a cancer-related diagnosis. Unfortunately, it has been used off label with alarming frequency in the last decade.

Fentanyl testing. Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid and its metabolites are often missed in urine drug screens. GC/MS or LCMS are relatively good at detecting it and are reasonable confirmatory tests.

Adverse Effects of Opioid Analgesics

Recommendations

In opioid naïve patients:

- Start opioids at low doses to avoid respiratory depression, which is most likely to occur in the first 24 hours. Use extra caution in patients with COPD or obstructive sleep apnea.

- Provide constipation prophylaxis.

- Consider anti-nausea medication.

When increasing opioid doses:

- Inform patients that temporary cognitive impairment may occur.

- If dosing increases to > 50 MME/day, prescribe naloxone to use if an overdose occurs.

With prolonged use of opioids, particularly with high doses:

- Consider that increased sensitivity to pain (opioid-induced hyperalgesia) may develop.

- Detoxification may be required.

Nearly 80% of patients using opioids experience adverse effects.97 The most common adverse effects are sedation, nausea, headache, pruritus, and constipation. Other effects can be confusion, hallucinations, nightmares, urinary retention, dizziness, and headache. Tolerance and regression of most adverse effects often occur quickly. Constipation and urinary retention (smooth muscle inhibitory effects) are more persistent.

The most serious potential adverse effect is respiratory depression accompanied by symptoms of sedation and confusion. It may occur with high dose administration in opioid naïve patients. Opioids, at therapeutic doses, depress respiratory rate and tidal volume. As CO2 rises, central chemoreceptors cause a compensatory increase in respiratory rate. Patients with impaired ventilatory reserve (COPD, asthma) are at greater risk of clinically significant respiratory depression. Tolerance to respiratory depression develops within just a few days.