NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Berkman ND, Chang E, Seibert J, et al. Management of High-Need, High-Cost Patients: A “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis, Realist Review, and Systematic Review [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021 Oct. (Comparative Effectiveness Review, No. 246.)

Management of High-Need, High-Cost Patients: A “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis, Realist Review, and Systematic Review [Internet].

Show detailsResults of Literature Searches

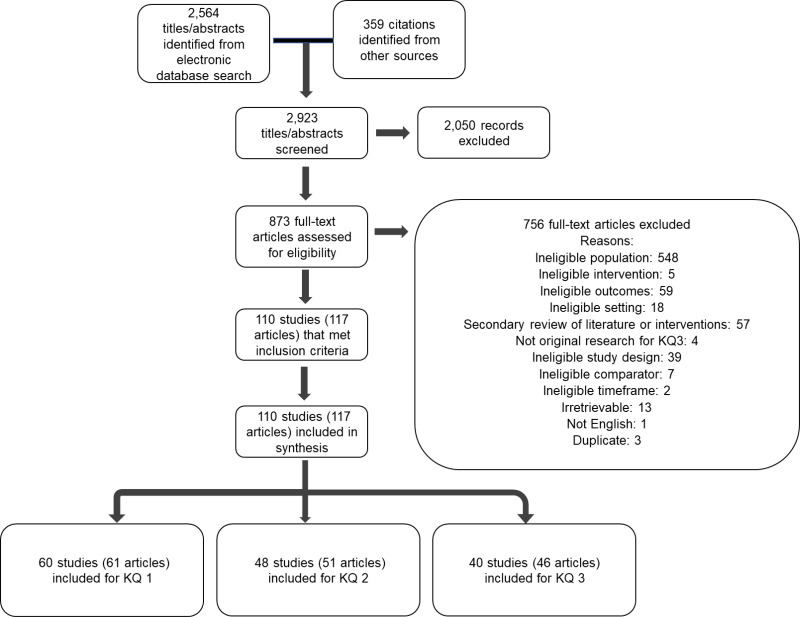

The electronic search, grey literature, and reference mining identified 2,923 citations. After title and abstract screening, 873 citations were retrieved for full-text review. A total of 110 studies (117 articles) met eligibility criteria. A total of 110 studies (117 articles) were included in the analyses.

Description of Included Studies

For KQ 1, we identified 60 studies (61 articles), of which 33 were cross sectional, 10 latent class, 11 predictive, and 6 qualitative.16–76

For KQ 2, we identified we identified 48 studies (51 articles).12, 17, 22, 27–29, 31, 49, 53, 55, 58, 61, 62, 77–114 As for unique KQ 2 includes, we identified 10 studies (10 articles).12, 78, 91, 93, 94, 104–106, 113, 114

For KQ 3, we identified 19 trials and 21 observational studies (46 articles). Five RCTs were assessed as having low risk of bias, and 14 RCTs (15 articles) were assessed as having some concerns for bias,79–82, 84, 86, 87, 90, 96, 97, 99, 108–112, 115–118 No observational studies were assessed as having low risk of bias, 13 observational studies (17 articles) were assessed as having some concerns for bias, and eight observational studies (9 articles) were assessed as having high risk of bias.83, 85, 88, 92, 95, 98, 100–103, 107, 119–133

List of Excluded Studies

- X1: Ineligible Population

- X2: Ineligible Intervention

- X3: Ineligible Comparator

- X4: Ineligible Outcome

- X5: Ineligible Time Frame

- X6: Setting/Country

- X7: Secondary Review of Literature or Interventions

- X8: Not Original Research for KQ 3

- X9: Study Design

- X10: Not English

- X11: Irretrievable

- X12: Duplicate

- 1.

- Magellan initiative targets high utilizers in private plans. Mental Health Weekly. 2000;10(32):1. PMID: 3493535. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 2.

- Hand-held devices ease burden of behavioral health assessment. Dis Manag Advis. 2002;8(10):152–6, 45. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 12422804]

- 3.

- Medicaid best buys: improving care management for high-need, high-cost beneficiaries. Hamilton, N.J.: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.; 2008. Exclusion Code: X4.

- 4.

- Medicaid best buys: critical strategies to focus on high-need, high-cost beneficiaries. Hamilton, N.J.: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.; 2010. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 5.

- Building the national care service. Norwich: Great Britain Stationary Office; 2010. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 6.

- ED diversion: multidisciplinary approach engages high utilizers, helps them better navigate the health care system. ED management: the monthly update on emergency department management. 2011;23(11):127–30. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 22043590]

- 7.

- CM program keeps high utilizers out of hospital. Hosp Case Manag. 2012;20(7):108–9. PMID: 104470969. Language: English. Entry Date: 20120711. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Nursing. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 22808541]

- 8.

- Hospitals collaborate to reduce ED overuse. Hosp Case Manag. 2012 Oct;20(10):151–3. PMID: 23084509. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 23091842]

- 9.

- Patient navigation for Medicaid frequent ED users. Yale University. 2013. https://www

.cochranelibrary .com/central/doi/10 .1002/central/CN-01579091/full. PMID: CN-01579091. Exclusion Code: X4. - 10.

- Identifying high utilizers of surgical care after colectomy. J Surg Res. 2014;186(2):495-. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.11.036. PMID: 93484679. Exclusion Code: X1. [CrossRef]

- 11.

- Programs focusing on high-need, high-cost populations. [Trenton, N.J.]: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.; 2016. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 12.

- Understanding the needs of different types of high-need patients and their caregivers. Commonwealth Fund; 2019. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 13.

- Community Care For High-Need Patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019 Jun;38(6):892–3. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00473. PMID: 31454082. Exclusion Code: X8. [PubMed: 31158014] [CrossRef]

- 14.

- Evaluation of a Multidisciplinary Care Coordination Program for Frequent Users of the Emergency Department. Prof Case Manag. 2019 Sep/Oct;24(5):E1–e2. doi: 10.1097/ncm.0000000000000388. PMID: 30593912. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 31369485] [CrossRef]

- 15.

- Extreme consumers of health care: patterns of care utilization in patients with multiple chronic conditions admitted to a novel integrated clinic. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2019;12:1075–83. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S214770. PMID: CN-02136481. Exclusion Code: X6. [PMC free article: PMC6935286] [PubMed: 31920324] [CrossRef]

- 16.

- Assertive Community Treatment for Alcohol Misuse Disorder Patients Who Are High Utilizers of Emergency Department Services (ARFA). Khoo Teck Puat Hospital. Jun 25, 2020. Exclusion Code: X11.

- 17.

- Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Read Guernsey J, Mackinnon NJ, et al. The association between a prolonged stay in the emergency department and adverse events in older patients admitted to hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011 Jul;20(7):564–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.034926. PMID: 21776300. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 21209130] [CrossRef]

- 18.

- Acosta AM, Lima MA. Frequent users of emergency services: associated factors and reasons for seeking care. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2015 Feb–Apr;23(2):337–44. doi: 10.1590/0104-1169.0072.2560. PMID: 26240244. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC4459009] [PubMed: 26039306] [CrossRef]

- 19.

- Adler-Milstein J. Assessing the impact of Medicare advantage on high-cost, high-need beneficiaries and exploring an intervention to improve outcomes. Michigan: Commonwealth Fund; 2017. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 20.

- Agarwal G, Lee J, McLeod B, et al. Social factors in frequent callers: a description of isolation, poverty and quality of life in those calling emergency medical services frequently. BMC Public Health. 2019 Jun 3;19(1):684. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6964-1. PMID: 31277151. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6547509] [PubMed: 31159766] [CrossRef]

- 21.

- Agarwal G, McDonough B, Angeles R, et al. Rationale and methods of a multicentre randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of a Community Health Assessment Programme with Emergency Medical Services (CHAP-EMS) implemented on residents aged 55 years and older in subsidised seniors’ housing buildings in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open. 2015 Jun 11;5(6):e008110. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008110. PMID: 26206441. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC4466604] [PubMed: 26068514] [CrossRef]

- 22.

- Agterberg J, Zhong F, Crabb R, et al. Cluster analysis application to identify groups of individuals with high health expenditures. Health Services & Outcomes Research Methodology. 2020;20(2/3):140–82. doi: 10.1007/s10742-020-00214-8. PMID: 145263707. Exclusion Code: X4. [CrossRef]

- 23.

- Aird P, Hansford P, O’Brien R, et al. The impact of frequent users of OOH services. Br J Gen Pract. 2001 Jun;51(467):494–5. PMID: 15094029. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC1314038] [PubMed: 11407062]

- 24.

- al Yousif N, Hussain HY, El Din Mhakluf MM. Health care services utilization and satisfaction among elderly in Dubai, UAE and some associated determinants. Middle East Journal of Age & Ageing. 2014;11(3):25–33. PMID: 96513555. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 25.

- Alderwick H, Hood-Ronick CM, Gottlieb LM. Medicaid Investments To Address Social Needs In Oregon And California. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019 May;38(5):774–81. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05171. PMID: 31059356. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 31059356] [CrossRef]

- 26.

- Alexander Billioux KV, Susan Anthony, Dawn Alley. Standardized Screening for Health-Related Social Needs in Clinical Settings The Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool. 2017. Exclusion Code: X2.

- 27.

- Alghanim SA, Alomar BA. Frequent use of emergency departments in Saudi public hospitals: implications for primary health care services. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015 Mar;27(2):Np2521–30. doi: 10.1177/1010539511431603. PMID: 25547107. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 22186384] [CrossRef]

- 28.

- Allen CG, Escoffery C, Satsangi A, et al. Strategies to improve the integration of community health workers into health care teams: “a little fish in a big pond”. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015 Sep 17;12:E154. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150199. PMID: 26875022. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC4576500] [PubMed: 26378900] [CrossRef]

- 29.

- Althaus F, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Jul;58(1):41–52 e42. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007. PMID: 21689565. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 21689565] [CrossRef]

- 30.

- Althaus F, Stucki S, Guyot S, et al. Characteristics of highly frequent users of a Swiss academic emergency department: a retrospective consecutive case series. Eur J Emerg Med. 2013 Dec;20(6):413–9. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32835e078e. PMID: 25139183. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 23337095] [CrossRef]

- 31.

- Altman D. A small group of patients account for a whole lot of spending. Axios. 2019. https://www

.axios.com /drug-prices-health-care-costs-spending-employers-63a65abc-0148-4f98-bd39-b30e4d3c9caf.html. Exclusion Code: X7. - 32.

- Alvarado LP. Mobile psychiatric services decrease readmission rates among high utilizers of emergency treatment services: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2021. Exclusion Code: X3.

- 33.

- Amarasingham R, Xie B, Karam A, et al. Using community partnerships to integrate health and social services for high-need, high-cost patients. Commonwealth Fund. 2018. https://www

.commonwealthfund .org/publications /issue-briefs/2018 /jan/using-community-partnerships-integrate-health-and-social. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 29320140] - 34.

- Anderson DR, Mangen DJ, Grossmeier JJ, et al. Comparing alternative methods of targeting potential high-cost individuals for chronic condition management. J Occup Environ Med. 2010 Jun;52(6):635–46. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181e31792. PMID: 15175823. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 20523235] [CrossRef]

- 35.

- Anderson GM. Program delivery for high-needs, high-cost populations: international perspectives on the way forward, phase I. University of Toronto, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation 2017. https://hsrproject

.nlm .nih.gov/view_hsrproj_record/20191229. Exclusion Code: X7. - 36.

- Andrews G, Sunderland M. Telephone case management reduces both distress and psychiatric hospitalization. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;43(9):809–11. doi: 10.1080/00048670903107617. PMID: 17515738. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 19670053] [CrossRef]

- 37.

- Angelelli J, Gifford D, Intrator O, et al. Access to postacute nursing home care before and after the BBA (Balanced Budget Act). Health Aff (Millwood). 2002 Sep–Oct;21(5):254–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.254. PMID: 12450957. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 12224890] [CrossRef]

- 38.

- Armstrong G, De Marchis E, Mix R, et al. Using Social Needs Screening and Patient Feedback for Complex Care. National Center for Complex Health and Social Needs; 2020. alcomplex

.care/research-policy /resources /webinars/using-social-needs-screening-and-patient-feedback-for-complex-care /2020. Exclusion Code: X1. - 39.

- Avila J, Jupiter D, Chavez-MacGregor M, et al. High-Cost Hospitalizations Among Elderly Patients With Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2019 May;15(5):e447–e57. doi: 10.1200/jop.18.00706. PMID: 30354887. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 30946640] [CrossRef]

- 40.

- Azogil-López LM, Pérez-Lázaro JJ, Ávila-Pecci P, et al. Effectiveness of a new model of telephone derivation shared between primary care and hospital care. Atencion primaria / Sociedad Espanola de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria. 2019;51(5):278–84. doi: 10.1016/j.aprim.2018.02.006. PMID: CN-02133656. Exclusion Code: X10. [PMC free article: PMC6836997] [PubMed: 29699717] [CrossRef]

- 41.

- Bagnall AM, South J, Forshaw MJ, et al. Self-care in primary care: findings from a longitudinal comparison study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013 Jan;14(1):29–39. doi: 10.1017/s1463423612000199. PMID: 24568286. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 22717510] [CrossRef]

- 42.

- Bailey JE, Surbhi S, Wan JY, et al. Effect of Intensive Interdisciplinary Transitional Care for High-Need, High-Cost Patients on Quality, Outcomes, and Costs: a Quasi-Experimental Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Sep;34(9):1815–24. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05082-8. PMID: 32245460. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6712187] [PubMed: 31270786] [CrossRef]

- 43.

- Baker JM, Grant RW, Gopalan A. A systematic review of care management interventions targeting multimorbidity and high care utilization. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Jan 30;18(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2881-8. PMID: 29382327. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5791200] [PubMed: 29382327] [CrossRef]

- 44.

- Balaban RB, Zhang F, Vialle-Valentin CE, et al. Impact of a Patient Navigator Program on Hospital-Based and Outpatient Utilization Over 180 Days in a Safety-Net Health System. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Sep;32(9):981–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4074-2. PMID: 28523476. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5570741] [PubMed: 28523476] [CrossRef]

- 45.

- Balfour ME, Zinn TE, Cason K, et al. Provider-payer partnerships as an engine for continuous quality improvement. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(6):623–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700533. PMID: 129890973. Language: English. Entry Date: In Process. Revision Date: 20180609. Publication Type: Article. Journal Subset: Biomedical. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 29493418] [CrossRef]

- 46.

- Barker SL, Maguire NJ, Das S, et al. Values-Based Interventions in Patient Engagement for Those with Complex Needs. Popul Health Manag. 2020;23(2):140–5. doi: 10.1089/pop.2019.0084. PMID: 142272277. Language: English. Entry Date: 20200320. Revision Date: 20200324. Publication Type: Article. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 31503526] [CrossRef]

- 47.

- Barsky AJ, Ahern DK, Bauer MR, et al. A randomized trial of treatments for high-utilizing somatizing patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1396–404. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2392-6. PMID: CN-00909578. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC3797340] [PubMed: 23494213] [CrossRef]

- 48.

- Bauman CA, Fillingham J, Keely-Dyck E, et al. An approach to interprofessional management of complex patients: a case report. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2019;63(2):119–25. PMID: 138594442. Language: English. Entry Date: 20190916. Revision Date: 20190926. Publication Type: Article. Exclusion Code: X6. [PMC free article: PMC6743649] [PubMed: 31564750]

- 49.

- Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Powers JD, et al. Using self-reported data to segment older adult populations with complex care needs. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2019 Apr 12;7(1):12. doi: 10.5334/egems.275. PMID: 31065556. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6484372] [PubMed: 31065556] [CrossRef]

- 50.

- Beach SR, Schulz R, Friedman EM, et al. Adverse Consequences of Unmet Needs for Care in High-Need/High-Cost Older Adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020 Jan 14;75(2):459–70. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby021. PMID: 30522388. Exclusion Code: X3. [PubMed: 29471360] [CrossRef]

- 51.

- Becker T, Steffen S, Puschner B. Discharge planning, an intervention study - and where to go next? Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(11)73744-0. PMID: CN-01782093. Exclusion Code: X1. [CrossRef]

- 52.

- Bedoya P, Neuhausen K, Dow AW, et al. Student Hotspotting: Teaching the Interprofessional Care of Complex Patients. Acad Med. 2018 Jan;93(1):56–9. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000001822. PMID: 28700461. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 28700461] [CrossRef]

- 53.

- Beesley VL, Smithers BM, O’Rourke P, et al. Variations in supportive care needs of patients after diagnosis of localised cutaneous melanoma: a 2-year follow-up study. Support Care Cancer. 2017 Jan;25(1):93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3378-9. PMID: 26389982. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 27562298] [CrossRef]

- 54.

- Beima-Sofie K, Begnel ER, Golden MR, et al. “It’s Me as a Person, Not Me the Disease”: Patient Perceptions of an HIV Care Model Designed to Engage Persons with Complex Needs. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020 Jun;34(6):267–74. doi: 10.1089/apc.2019.0310. PMID: 31670693. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC7262637] [PubMed: 32484744] [CrossRef]

- 55.

- Bélanger E, McHugh J, Meyers DJ, et al. Characteristics of Top-Performing Hospitals Caring for High-Need Medicare Beneficiaries. Popul Health Manag. 2020;23(4):313–8. doi: 10.1089/pop.2019.0145. PMID: 144824249. Language: English. Entry Date: 20200813. Revision Date: 20200813. Publication Type: Article. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 31816254] [CrossRef]

- 56.

- Bellon JA, Rodriguez-Bayon A, Luna JD, et al. Successful GP intervention with frequent attenders in primary care: randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2008 May;58(550):324–30. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X280182. PMID: WOS:000256654700006. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC2435670] [PubMed: 18482486] [CrossRef]

- 57.

- Bergenstal TD, Reitsema J, Heppner P, et al. Personalized Care Plans: Are They Effective in Decreasing ED Visits and Health Care Expenditure Among Adult Super-Utilizers? J Emerg Nurs. 2020 Jan;46(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2019.09.001. PMID: 32750132. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 31685338] [CrossRef]

- 58.

- Bergeron P, Courteau J, Vanasse A. Proximity and emergency department use: multilevel analysis using administrative data from patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Can Fam Physician. 2015 Aug;61(8):e391–7. PMID: 26747456. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC4541449] [PubMed: 26505061]

- 59.

- Bergh H, Marklund B. Characteristics of frequent attenders in different age and sex groups in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2003 Sep;21(3):171–7. doi: 10.1080/02813430310001149. PMID: WOS:000185314100010. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 14531510] [CrossRef]

- 60.

- Berghofer A, Hartwich A, Bauer M, et al. Efficacy of a systematic depression management program in high utilizers of primary care: a randomized trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012 Sep 3;12:298. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-298. PMID: 25527472. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC3489593] [PubMed: 22943609] [CrossRef]

- 61.

- Berghöfer A, Roll S, Bauer M, et al. Screening for depression and high utilization of health care resources among patients in primary care. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(7):753–8. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9700-4. PMID: 103896118. Language: English. Entry Date: 20140924. Revision Date: 20151001. Publication Type: Journal Article. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 24449430] [CrossRef]

- 62.

- Berkowitz SA. Capsule Commentary on Schickedanz et al., Impact of Social Needs Navigation on Utilization Among High-Utilizers in a Large Integrated Health System: a Quasi-Experimental Study. JGIM: Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2019;34(11):2582-. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05296-w. PMID: 139599661. Exclusion Code: X8. [PMC free article: PMC6848514] [PubMed: 31452028] [CrossRef]

- 63.

- Bertoli-Avella AM, Haagsma JA, Van Tiel S, et al. Frequent users of the emergency department services in the largest academic hospital in the Netherlands: a 5-year report. Eur J Emerg Med. 2017 Apr;24(2):130–5. doi: 10.1097/mej.0000000000000314. PMID: 28863030. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 26287805] [CrossRef]

- 64.

- Bieler G, Paroz S, Faouzi M, et al. Social and medical vulnerability factors of emergency department frequent users in a universal health insurance system. Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Jan;19(1):63–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01246.x. PMID: 21701913. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 22221292] [CrossRef]

- 65.

- Bilazarian A. High-need high-cost patients: A Concept Analysis. Nurs Forum. 2020. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12500. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 32851669] [CrossRef]

- 66.

- Billett J, Cowie MR, Gatzoulis MA, et al. Comorbidity, healthcare utilisation and process of care measures in patients with congenital heart disease in the UK: cross-sectional, population-based study with case-control analysis. Heart. 2008 Sep;94(9):1194–9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.122671. PMID: 17610000. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 17646191] [CrossRef]

- 67.

- Bischoff RJ, Hollist CS, Patterson J, et al. Providers’ perspectives on troublesome overusers of medical services. Families, Systems, & Health. 2007;25(4):392–403. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.25.4.392. PMID: 2007-19994-004. Exclusion Code: X1. [CrossRef]

- 68.

- Blair M. Organizations provide $8.7 million to launch a national center to improve care for complex patients. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2016. https://www

.rwjf.org /en/library/articles-and-news /2016/03/organizations-provide-8-7-million-to-launch-national-center .html. Exclusion Code: X7. - 69.

- Blakey R, Court G, Peaker A, et al. High service users: does the clinical psychologist have a role? Health Bull (Edinb). 2000 May;58(3):203–9. PMID: 11860388. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 12813826]

- 70.

- Blank FS, Li H, Henneman PL, et al. A descriptive study of heavy emergency department users at an academic emergency department reveals heavy ED users have better access to care than average users. J Emerg Nurs. 2005 Apr;31(2):139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2005.02.008. PMID: 15047073. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 15834378] [CrossRef]

- 71.

- Bledsoe SE. Adult health care services and psychiatric disorders: the use and costs of health care services in a low income, minority population coming to an urban primary care clinic: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2007. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 72.

- Bleich SN, Sherrod C, Chiang A, et al. Systematic review of programs treating high-need and high-cost people with multiple chronic diseases or disabilities in the United States, 2008–2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015 Nov 12;12:E197. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150275. Exclusion Code: X7. [PMC free article: PMC4651160] [PubMed: 26564013] [CrossRef]

- 73.

- Blumenthal D, Abrams MK. Tailoring complex care management for high-need, high-cost patients. JAMA. 2016 Oct 25;316(16):1657–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12388. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 27669168] [CrossRef]

- 74.

- Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, et al. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients - an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 8;375(10):909–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1608511. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 27602661] [CrossRef]

- 75.

- Bobo WV, Hoge CW, Messina MA, et al. Characteristics of repeat users of an inpatient psychiatry service at a large military tertiary care hospital. Mil Med. 2004 Aug;169(8):648–53. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.8.648. PMID: 15576522. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 15379078] [CrossRef]

- 76.

- Bodenmann P, Baggio S, Iglesias K, et al. Characterizing the vulnerability of frequent emergency department users by applying a conceptual framework: a controlled, cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2015 Dec 9;14:146. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0277-5. PMID: 27142996. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC4673736] [PubMed: 26645272] [CrossRef]

- 77.

- Bodenmann P, Velonaki VS, Griffin JL, et al. Case management may reduce emergency department frequent use in a universal health coverage system: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 May;32(5):508–15. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3789-9. PMID: 27578689. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5400747] [PubMed: 27400922] [CrossRef]

- 78.

- Boehmer KR, Abu Dabrh AM, Gionfriddo MR, et al. Does the chronic care model meet the emerging needs of people living with multimorbidity? A systematic review and thematic synthesis. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0190852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190852. PMID: 29420543. Exclusion Code: X7. [PMC free article: PMC5805171] [PubMed: 29420543] [CrossRef]

- 79.

- Boling PA, Leff B. Comprehensive longitudinal health care in the home for high-cost beneficiaries: a critical strategy for population health management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014 Oct;62(10):1974–6. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13049. PMID: 25960393. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 25294407] [CrossRef]

- 80.

- Bornstein D. The 5 percent: solutions reporting on care for the nation’s sickest. Solutions Journalism Network, Inc.: Commonwealth Fund; 2016. Exclusion Code: X7.

- 81.

- Bradley EH. Identifying effective strategies for coordinating health care and social services for high-need, high-cost patients. Yale University, Yale School of Public Health 2015. https://www

.commonwealthfund .org/grants/identifying-effective-strategies-coordinating-health-care-and-social-services-high-need-high. Exclusion Code: X7. - 82.

- Brannon E, Wang T, Lapedis J, et al. Towards a learning health system to reduce emergency department visits at a population level. AMIA Symposium; 2018. Annual Symposium proceedings; 2018. pp. 295–304. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6371247] [PubMed: 30815068]

- 83.

- Braveman P, Dekker M, Egerter S, et al. How does housing affect health? An examination of the many ways in which housing can influence health and strategies to improve health through emphasis on healthier homes. 2011. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 84.

- Breland JY, Chee CP, Zulman DM. Racial differences in chronic conditions and sociodemographic characteristics among high-utilizing veterans. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015 Jun;2(2):167–75. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0060-0. PMID: 26147126. Exclusion Code: X4. [PMC free article: PMC6200449] [PubMed: 26863335] [CrossRef]

- 85.

- Brenner JC. Jeffrey C Brenner: on driving down the cost of care. Healthc Financ Manage. 2013 Jan;67(1):72–5. PMID: 23360057. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 23360057]

- 86.

- Brewster AL, Brault MA, Tan AX, et al. Patterns of collaboration among health care and social services providers in communities with lower health care utilization and costs. Health Serv Res. 2018 Aug;53 Suppl 1:2892–909. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12775. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6056597] [PubMed: 28925041] [CrossRef]

- 87.

- Brian W. Powers SP, Nupur Mehta. Impact of Complex Care Management on Spending and Utilization for High-Need, High-Cost Medicaid Patients. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2020. Exclusion Code: X12. [PubMed: 32059101]

- 88.

- Bronsky ES, McGraw C, Johnson R, et al. CARES: a community-wide collaboration identifies super-utilizers and reduces their 9-1-1 call, emergency department, and hospital visit rates. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017 Nov–Dec;21(6):693–9. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2017.1335820. PMID: 25469750. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 28657819] [CrossRef]

- 89.

- Brooks EM, Winship JM, Kuzel AJ. A “Behind-the-Scenes” Look at Interprofessional Care Coordination: How Person-Centered Care in Safety-Net Health System Complex Care Clinics Produce Better Outcomes. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2020 Apr–Jun;20(2):10. doi: 10.5334/ijic.4734. PMID: WOS:000550985100007. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC7207252] [PubMed: 32405282] [CrossRef]

- 90.

- Brown AF, Behforouz H, Shah A, et al. The care connections program: A randomized trial of community health workers to improve care for medically and socially complex patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(SUPPL 1):S288. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05890-3. Exclusion Code: X1. [CrossRef]

- 91.

- Brown KE, Fiellin DA, Chawarski MC, et al. A randomized trial of primary intensive care to reduce hospital admissions in high utilizers. J Gen Intern Med. 2002 Apr;17:121-. PMID: WOS:000175158200432. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 92.

- Brown KE, Levine JM, Fiellin DA, et al. Primary intensive care: pilot study of a primary care-based intervention for high-utilizing patients. Dis Manag. 2005 Jun;8(3):169–77. doi: 10.1089/dis.2005.8.169. PMID: 16359548. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 15966782] [CrossRef]

- 93.

- Broyles J. Strategies to promulgate advanced illness care models that work. Coalition to Transform Advanced Care. Washington, DC: 2013. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 94.

- Bryk J, Fischer GS, Lyons A, et al. Improvement in quality metrics by the UPMC enhanced care program: a novel super-utilizer program. Popul Health Manag. 2018 Jun;21(3):217–21. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0064. PMID: 27612609. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 28945512] [CrossRef]

- 95.

- Buchanan D, Doblin B, Sai T, et al. The effects of respite care for homeless patients: a cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2006 Jul;96(7):1278–81. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2005.067850. PMID: 16735635. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC1483848] [PubMed: 16735635] [CrossRef]

- 96.

- Buck JA, Teich JL, Miller K. Use of mental health and substance abuse services among high-cost Medicaid enrollees. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2003 Sep;31(1):3–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1026089422101. PMID: 26850904. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 14650645] [CrossRef]

- 97.

- Buja A, Claus M, Perin L, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in high-need, high-cost elderly patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208875. PMID: 29560049. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6296662] [PubMed: 30557384] [CrossRef]

- 98.

- Buja A, Rivera M, De Battisti E, et al. Multimorbidity and Hospital Admissions in High-Need, High-Cost Elderly Patients. J Aging Health. 2020 Jun/Jul;32(5–6):259–68. doi: 10.1177/0898264318817091. PMID: 31682499. Exclusion Code: X6. [PubMed: 30522388] [CrossRef]

- 99.

- Burns C, Wang NE, Goldstein BA, et al. Characterization of young adult emergency department users: evidence to guide policy. J Adolesc Health. 2016 Dec;59(6):654–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.011. PMID: 27605647. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 27613220] [CrossRef]

- 100.

- Burns J. Treating Super Utilizers in Rural Pennsylvania. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Princeton, NJ: 2013. https://www

.rwjf.org /en/library/articles-and-news /2013/09/treating-superusers-in-rural-pennsylvania .html. Exclusion Code: X1. - 101.

- Burns J. Cleveland Medical Center aims to improve care for super utilizers. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Princeton, NJ: 2013. https://www

.rwjf.org /en/library/articles-and-news /2013/09/cleveland-improves-care-for-super-utilizers.html. Exclusion Code: X1. - 102.

- Bush H. Caring for the costliest. (Cover story). H&HN: Hospitals & Health Networks. 2012;86(11):24–9. PMID: 83779325. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 23214040]

- 103.

- Bush H. Tackling the high cost of chronic disease. Hosp Health Netw. 2012 Oct;86(10):34–6, 8, 40. PMID: 26454353. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 23163172]

- 104.

- Bynum JPW. Measuring what matters most to people with complex needs. Health Aff (Millwood). Bethesda, MD: Health Affairs; 2018. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 105.

- Bynum JPW, Austin A, Carmichael D, et al. High-Cost Dual Eligibles’ Service Use Demonstrates The Need For Supportive And Palliative Models Of Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017 Jul 1;36(7):1309–17. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0157. PMID: 31029256. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5633373] [PubMed: 28679819] [CrossRef]

- 106.

- California Health Care Foundation. Data symposium and webinar on high utilizers of Medi-Cal Services. Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; 2015. https://www

.chcf.org /event/data-symposium-and-webinar-on-high-utilizers-of-medi-cal-services/2019. Exclusion Code: X1. - 107.

- California Health Care Foundation. Integrated clinics for high utilizers conference. Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; 2015. https://www

.chcf.org /event/integrated-clinics-for-high-utilizers-conference/2019. Exclusion Code: X1. - 108.

- California Health Care Foundation. Care integration for patients with complex needs. California Health Care Foundation. Oakland, CA: 2017. https://www

.chcf.org /project/care-integration-for-patients-with-complex-needs/. Exclusion Code: X1. - 109.

- California Health Care Foundation. CIN Webinar Series — The ROI for addressing social needs in health care (#2). Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; 2018. https://www

.chcf.org /event/cin-webinar-series-roi-addressing-social-needs-health-care-2/2019. Exclusion Code: X1. - 110.

- Capp R, Rosenthal MS, Desai MM, et al. Characteristics of Medicaid enrollees with frequent ED use. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Sep;31(9):1333–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.05.050. PMID: 23850143. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 23850143] [CrossRef]

- 111.

- Capp R, Zane R. Using emergency department community health workers as a bridge to ongoing care for frequent ED users. Value and Quality Innovations in Acute and Emergency Care. 2017:209–14. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 112.

- Carney KJL. PRACTITIONER APPLICATION: An Evaluation of Interprofessional Patient Navigation Services in High Utilizers at a County Tertiary Teaching Health System. J Healthc Manag. 2020 Jan–Feb;65(1):71–2. doi: 10.1097/jhm-d-19-00237. PMID: WOS:000561759100012. Exclusion Code: X8. [PubMed: 31913242] [CrossRef]

- 113.

- Carpiac-Claver M, Guzman JS, Castle SC. The Comprehensive Care Clinic. Health Soc Work. 2007 Aug;32(3):219–23. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.3.219. PMID: 17896679. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 17896679] [CrossRef]

- 114.

- Carroll CP, Carlton Jr H, Fagan P, et al. The course and correlates of high hospital utilization in sickle cell disease: evidence from a large, urban Medicaid managed care organization. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(10):666–70. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21515. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC2783233] [PubMed: 19743465] [CrossRef]

- 115.

- Castillo EM, Brennan JJ, Killeen JP, et al. Identifying frequent users of emergency department resources. J Emerg Med. 2014 Sep;47(3):343–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.03.014. PMID: 27604932. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 24813059] [CrossRef]

- 116.

- Center for Health Care Strategies. Medicaid-financed services in supportive housing for high-need homeless beneficiaries. 2012. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 117.

- . The Super-Utilizer Summit: resources to support emerging programs. Super-Utilizer Summit; 2013; Alexandra, Virginia. 2442: Center for Health Care Strategies. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 118.

- Center for Integrative Medicine. Webinar — new online resources for complex care. Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; 2015. https://www

.chcf.org /event/webinar-new-online-resources-for-complex-care/2019. Exclusion Code: X1. - 119.

- Chambers C, Chiu S, Katic M, et al. High utilizers of emergency health services in a population-based cohort of homeless adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(S2):S302–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301397. PMID: 104161876. Language: English. Entry Date: 20131126. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC3969147] [PubMed: 24148033] [CrossRef]

- 120.

- Chan B, Edwards ST, Devoe M, et al. The SUMMIT ambulatory-ICU primary care model for medically and socially complex patients in an urban federally qualified health center: study design and rationale. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018;13(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s13722-018-0128-y. PMID: CN-01925167. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6295087] [PubMed: 30547847] [CrossRef]

- 121.

- Chan B, Edwards ST, Mitchell M, et al. Can an intensive ambulatory care intervention improve the experience of high-utilizing patients?: 6-month outcomes of the summit randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(2):S151–. doi: 10.1007/11606.1525-1497. PMID: CN-01976812. Exclusion Code: X1. [CrossRef]

- 122.

- Chan B, Mitchell M, Edwards ST, et al. Implementation and evaluation of summit, an ambulatory intensive care (A-ICU) model of primary care for high-utilizersata healthcare for the homeless site. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):791–2. PMID: CN-01606174. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 123.

- Chan BT, Ovens HJ. Frequent users of emergency departments. Do they also use family physicians’ services? Can Fam Physician. 2002 Oct;48:1654–60. PMID: 12870409. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC2213944] [PubMed: 12449550]

- 124.

- Chandler D, Spicer G. Capitated assertive community treatment program savings: system implications. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2002;30(1):3–19. PMID: CN-00412904. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 12546253]

- 125.

- Chang E. Intensive Primary Care via Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT) Intensive Management @ VA. 2019. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 126.

- Chang ET, Raja PV, Stockdale SE, et al. What are the key elements for implementing intensive primary care? A multisite Veterans Health Administration case study. Healthc (Amst). 2018 Dec;6(4):231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.10.001. PMID: 29102480. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 29102480] [CrossRef]

- 127.

- Chang ET, Zulman DM, Asch SM, et al. An operations-partnered evaluation of care redesign for high-risk patients in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA): study protocol for the PACT Intensive Management (PIM) randomized quality improvement evaluation. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018 Jun;69:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.04.008. PMID: 29698772. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 29698772] [CrossRef]

- 128.

- Chang HY, Boyd CM, Leff B, et al. Identifying Consistent High-cost Users in a Health Plan: Comparison of Alternative Prediction Models. Med Care. 2016 Sep;54(9):852–9. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000566. PMID: 27521041. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 27326548] [CrossRef]

- 129.

- Chapman H, Farndon L, Matthews R, et al. Okay to Stay? A new plan to help people with long-term conditions remain in their own homes. Primary Health Care Research & Development (Cambridge University Press / UK). 2019;20:N.PAG-N.PAG. doi: 10.1017/S1463423618000786. PMID: 134961288. Language: English. Entry Date: 20190302. Revision Date: 20190304. Publication Type: Article. Exclusion Code: X6. [PMC free article: PMC6476400] [PubMed: 30428937] [CrossRef]

- 130.

- Chaput YJ, Lebel MJ. An examination of the temporal and geographical patterns of psychiatric emergency service use by multiple visit patients as a means for their early detection. BMC Psychiatry. 2007 Oct 29;7:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-7-60. PMID: 17493977. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC2190759] [PubMed: 17963530] [CrossRef]

- 131.

- Chaput YJ, Lebel MJ. Demographic and clinical profiles of patients who make multiple visits to psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatr Serv. 2007 Mar;58(3):335–41. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.335. PMID: 16859808. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 17325106] [CrossRef]

- 132.

- Chen BK, Cheng X, Bennett K, et al. Travel distances, socioeconomic characteristics, and health disparities in nonurgent and frequent use of hospital emergency departments in South Carolina: a population-based observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015 May 16;15:203. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0864-6. PMID: 25970845. Exclusion Code: X4. [PMC free article: PMC4448557] [PubMed: 25982735] [CrossRef]

- 133.

- Cherner R, Ecker J, Louw A, et al. Lessons learned from piloting a pain assessment program for high frequency emergency department users. Scand J Pain. 2019 Jul 26;19(3):545–52. doi: 10.1515/sjpain-2018-0128. PMID: 30834969. Exclusion Code: X6. [PubMed: 31031261] [CrossRef]

- 134.

- Chernof B, McClellan M. Form follows funding: opportunities for advancing outcomes for complex care patients using alternative payment methods. Health Affairs Blog. Bethesda, MD: Health Affairs; 2018. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 135.

- Chhabra M, Spector E, Demuynck S, et al. Assessing the relationship between housing and health among medically complex, chronically homeless individuals experiencing frequent hospital use in the United States. Health Soc Care Community. 2020 Jan;28(1):91–9. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12843. PMID: 30629016. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 31476092] [CrossRef]

- 136.

- Chiu Y, Racine-Hemmings F, Dufour I, et al. Statistical tools used for analyses of frequent users of emergency department: a scoping review. Bmj Open. 2019 May;9(5). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027750. PMID: WOS:000471192800303. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6537981] [PubMed: 31129592] [CrossRef]

- 137.

- Chiu YM, Vanasse A, Courteau J, et al. Persistent frequent emergency department users with chronic conditions: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229022. PMID: 30780151. Exclusion Code: X6. [PMC free article: PMC7015381] [PubMed: 32050010] [CrossRef]

- 138.

- Chuang E, Pourat N, Haley LA, et al. Integrating Health And Human Services In California’s Whole Person Care Medicaid 1115 Waiver Demonstration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020 Apr;39(4):639–48. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01617. PMID: WOS:000523599600015. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 32250689] [CrossRef]

- 139.

- Chukmaitov AS, Tang A, Carretta HJ, et al. Characteristics of all, occasional, and frequent emergency department visits due to ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in Florida. J Ambul Care Manage. 2012 Apr–Jun;35(2):149–58. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e318244d222. PMID: 23091842. Exclusion Code: X3. [PubMed: 22415289] [CrossRef]

- 140.

- Claxton G, Rae M, Levitt L. A look at people who have persistently high spending on health care. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2019. https://www

.kff.org/health-costs /issue-brief /a-look-at-people-who-have-persistently-high-spending-on-health-care/. Exclusion Code: X7. - 141.

- ClinicalTrials

.gov. Contra Costa Health Services Whole Person Care (CommunityConnect) Program Evaluation. https: //clinicaltrials .gov/show/NCT04000074. 2019. PMID: CN-01952848. Exclusion Code: X9. - 142.

- ClinicalTrials

.gov. High Risk Outpatient Intern-led Care (HeROIC) Clinic Initiative. https: //clinicaltrials .gov/show/NCT04375189. 2020. PMID: CN-02103718. Exclusion Code: X11. - 143.

- CMS. Integrated care resource center available to all states. Resources available to all states to coordinate care for high-cost, high-need beneficiaries. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2017. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 144.

- Cohen D, Wodchis WP, Calzavara A. Can high-cost spending in the community signal admission to hospital? A dynamic modeling study for urgent and elective cardiovascular patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Nov 15;18(1):861. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3639-z. PMID: 23297608. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6238318] [PubMed: 30442140] [CrossRef]

- 145.

- Coles S. Strategies to Improve Corporate Financial Investment in Care Coordination Programs. Walden University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2018. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 146.

- Colla C. Evaluating the formation and performance of accountable care organizations: focus on high-need, high-cost populations. Dartmouth College, Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. 2014. Exclusion Code: X7.

- 147.

- Colla C, Yang WD, Mainor AJ, et al. Organizational integration, practice capabilities, and outcomes in clinically complex medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2020 Dec;55:1085–97. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13580. PMID: WOS:000583295700001. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC7720705] [PubMed: 33104254] [CrossRef]

- 148.

- Collins L, Sicks S, Hass RW, et al. Self-efficacy and empathy development through interprofessional student hotspotting. Journal of Interprofessional Care.4. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1712337. PMID: WOS:000523149400001. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 32233896] [CrossRef]

- 149.

- Connors JDN, Binkley BL, Graff JC, et al. How patient experience informed the SafeMed Program: Lessons learned during a Health Care Innovation Award to improve care for super-utilizers. Healthcare-the Journal of Delivery Science and Innovation. 2019 Mar;7(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2018.02.002. PMID: WOS:000461053700004. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 29477610] [CrossRef]

- 150.

- Considine JT. A Feasibility Study for an Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Led Community Engagement Program. Shepherd University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2018. Exclusion Code: X4.

- 151.

- Cook LJ, Knight S, Junkins EP, Jr., et al. Repeat patients to the emergency department in a statewide database. Acad Emerg Med. 2004 Mar;11(3):256–63. PMID: 11827601. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 15001405]

- 152.

- Cornell PY, Halladay CW, Ader J, et al. Embedding Social Workers In Veterans Health Administration Primary Care Teams Reduces Emergency Department Visits. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020 Apr;39(4):603–12. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01589. PMID: WOS:000523599600011. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 32250673] [CrossRef]

- 153.

- Costi S, Pellegrini M, Cavuto S, et al. Occupational therapy in rehabilitation of complex patients: protocol for a superiority randomized controlled trial. Journal of interprofessional care. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1711720. PMID: CN-02086974. Exclusion Code: X11. [PubMed: 32013621] [CrossRef]

- 154.

- Coughlin TA, Long SK. Health care spending and service use among high-cost Medicaid beneficiaries, 2002–2004. Inquiry. 2009 Winter;46(4):405–17. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_46.4.405. PMID: 28723691. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 20184167] [CrossRef]

- 155.

- Couture EM, Chouinard MC, Fortin M, et al. The relationship between health literacy and quality of life among frequent users of health care services: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017 Jul 6;15(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0716-7. PMID: 27862572. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5500997] [PubMed: 28683743] [CrossRef]

- 156.

- Couture EM, Chouinard MC, Fortin M, et al. The relationship between health literacy and patient activation among frequent users of healthcare services: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018 Mar 9;19(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0724-7. PMID: 30118627. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5845227] [PubMed: 29523095] [CrossRef]

- 157.

- Cox WK, Penny LC, Statham RP, et al. Admission intervention team: medical center based intensive case management of the seriously mentally ill. Care Manag J. 2003 Winter;4(4):178–84. PMID: 15763120. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 15628650]

- 158.

- Craig C, Stiefel M, Carr E, et al. WIHI: when everyone knows your name: identifying patients with complex needs. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2015. Exclusion Code: X7.

- 159.

- Craig C ED, Whittington J. Care Coordination Model: Better Care at Lower Cost for People with Multiple Health and Social Needs. IHI. 2011. Exclusion Code: X11.

- 160.

- Crane D, Christenson J. The medical offset effect: patterns in outpatient services reduction for high utilizers of health care. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal. 2008;30(2):127–38. doi: 10.1007/s10591-008-9058-2. PMID: 31368504. Exclusion Code: X1. [CrossRef]

- 161.

- Crane M, Warnes AM. Primary health care services for single homeless people: defects and opportunities. Fam Pract. 2001 Jun;18(3):272–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.3.272. PMID: 12195545. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 11356733] [CrossRef]

- 162.

- Cruwys T, Wakefield JRH, Sani F, et al. Social isolation predicts frequent attendance in primary care. Ann Behav Med. 2018 Oct;52(10):817–29. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax054. PMID: WOS:000449052300001. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 30212847] [CrossRef]

- 163.

- Cullen W, O’Brien S, O’Carroll A, et al. Chronic illness and multimorbidity among problem drug users: a comparative cross sectional pilot study in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2009 Apr 21;10:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-25. PMID: 17466465. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC2678984] [PubMed: 19383141] [CrossRef]

- 164.

- Cunningham PJ. Predicting high-cost privately insured patients based on self-reported health and utilization data. Am J Manag Care. 2017 Jul 1;23(7):e215–e22. PMID: 27914968. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 28850789]

- 165.

- Curtin CM, Suarez PA, Di Ponio LA, et al. Who are the women and men in Veterans Health Administration’s current spinal cord injury population? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(3):351–60. PMID: 22606057. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 22773195]

- 166.

- Dang S, Ruiz DI, Klepac L, et al. Key Characteristics for Successful Adoption and Implementation of Home Telehealth Technology in Veterans Affairs Home-Based Primary Care: An Exploratory Study. Telemed J E Health. 2019 Apr;25(4):309–18. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0009. PMID: 30887432. Exclusion Code: X11. [PubMed: 29969381] [CrossRef]

- 167.

- Darke S, Havard A, Ross J, et al. Changes in the use of medical services and prescription drugs among heroin users over two years. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007 Mar;26(2):153–9. doi: 10.1080/09595230601146660. PMID: 17325106. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 17364850] [CrossRef]

- 168.

- Das LT, Abramson EL, Kaushal R. High-need, high-cost patients offer solutions for improving their care and reducing costs. NEJM Catal. 2019;2019. Exclusion Code: X7.

- 169.

- Das LT, Kaushal R, Garrison K, et al. Drivers of preventable high health care utilization: a qualitative study of patient, physician and health system leader perspectives. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2020;25(4):220–8. doi: 10.1177/1355819619873685. PMID: 145701247. Language: English. Entry Date: 20200922. Revision Date: 20200922. Publication Type: Article. Exclusion Code: X12. [PubMed: 31505976] [CrossRef]

- 170.

- Davis A, Osuji T, Chen A, et al. Data-driven decision making for interventions with complex needs’ patients: Identifying the right target population. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(SUPPL 1):75. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13433. Exclusion Code: X7. [CrossRef]

- 171.

- Davis AC, Osuji TA, Chen J, et al. Identifying Populations with Complex Needs: Variation in Approaches Used to Select Complex Patient Populations. Popul Health Manag. 2020. doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0153. Exclusion Code: X7. [PubMed: 32941105] [CrossRef]

- 172.

- Davis JW, Chung R, Juarez DT. Prevalence of comorbid conditions with aging among patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Hawaii Med J. 2011 Oct;70(10):209–13. PMID: 20106475. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC3215980] [PubMed: 22162595]

- 173.

- Davis R, Nuamah A. Identifying “Rising Risk” Populations: Early Lessons from the Complex Care Innovation Lab. Center for Health Care Strategies; 2020. Exclusion Code: X2.

- 174.

- Davis R, Somers SA. A collective national approach to fostering innovation in complex care. Healthc (Amst). 2018 Mar;6(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.05.003. PMID: 28673816. Exclusion Code: X7. [PubMed: 28673816] [CrossRef]

- 175.

- de Miguel-Diez J, Lopez-de-Andres A, Herandez-Barrera V, et al. Effect of the economic crisis on the use of health and home care services among Spanish COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:725–39. doi: 10.2147/copd.S150308. PMID: 28374978. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5836665] [PubMed: 29535513] [CrossRef]

- 176.

- Deacon B, Lickel J, Abramowitz JS. Medical utilization across the anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(2):344–50. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.004. PMID: 19197621. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 17420113] [CrossRef]

- 177.

- Delaney RK, Sisco-Taylor B, Fagerlin A, et al. A systematic review of intensive outpatient care programs for high-need, high-cost patients. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(5):1187–99. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa017. Exclusion Code: X7. [PubMed: 33044534] [CrossRef]

- 178.

- Delcher C, Yang C, Ranka S, et al. Variation in outpatient emergency department utilization in Texas Medicaid: a state-level framework for finding “superutilizers”. Int J Emerg Med. 2017 Dec 4;10(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12245-017-0157-4. PMID: 29204728. Exclusion Code: X9. [PMC free article: PMC5714939] [PubMed: 29204728] [CrossRef]

- 179.

- Dent A, Hunter G, Webster AP. The impact of frequent attenders on a UK emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010 Dec;17(6):332–6. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328335623d. PMID: 20136800. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 20038842] [CrossRef]

- 180.

- Dent AW, Phillips GA, Chenhall AJ, et al. The heaviest repeat users of an inner city emergency department are not general practice patients. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2003 Aug;15(4):322–9. PMID: 11502954. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 14631698]

- 181.

- Dew MA, Goycoolea JM, Harris RC, et al. An internet-based intervention to improve psychosocial outcomes in heart transplant recipients and family caregivers: development and evaluation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004 Jun;23(6):745–58. PMID: 15182240. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 15366436]

- 182.

- Di Lorenzo R, Sagona M, Landi G, et al. The revolving door phenomenon in an Italian acute psychiatric ward: a 5-year retrospective analysis of the potential risk factors. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204(9):686–92. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000540. PMID: 118071724. Language: English. Entry Date: 20180723. Revision Date: 20171231. Publication Type: journal article. Journal Subset: Biomedical. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 27227558] [CrossRef]

- 183.

- Di Mauro R, Di Silvio V, Bosco P, et al. Case management programs in emergency department to reduce frequent user visits: a systematic review. Acta Biomed. 2019 Jul 8;90(6-s):34–40. doi: 10.23750/abm.v90i6-S.8390. PMID: 31059373. Exclusion Code: X7. [PMC free article: PMC6776176] [PubMed: 31292413] [CrossRef]

- 184.

- Diaz T. In Memoriam. Patient Educ Couns. 2020 Jun;103(6):1258–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.11.027. PMID: WOS:000553018800024. Exclusion Code: X8. [CrossRef]

- 185.

- DiPietro BY. Medicaid accountable care organizations: a case study with Hennepin Health. 2018 May 2018. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 186.

- DiPietro BY, Kindermann D, Schenkel SM. Ill, itinerant, and insured: the top 20 users of emergency departments in Baltimore city. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:726568. doi: 10.1100/2012/726568. PMID: 22162595. Exclusion Code: X4. [PMC free article: PMC3345528] [PubMed: 22606057] [CrossRef]

- 187.

- Doheny M, Agerholm J, Orsini N, et al. Socio-demographic differences in the frequent use of emergency department care by older persons: a population-based study in Stockholm County. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Mar 29;19(1):202. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4029-x. PMID: 29620961. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6440084] [PubMed: 30922354] [CrossRef]

- 188.

- Dollard J, Harvey G, Dent E, et al. Older people who are frequent users of acute care: a symptom of fragmented care? A case series report on patients’ pathways of care. J Frailty Aging. 2018;7(3):193–5. doi: 10.14283/10.14283/jfa.2018.12. PMID: 29305202. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 30095151] [CrossRef]

- 189.

- Dombrowski JC, Ramchandani M, Dhanireddy S, et al. The Max Clinic: medical care designed to engage the hardest-to-reach persons living with HIV in Seattle and King County, Washington. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018 Apr;32(4):149–56. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0313. PMID: 30670044. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5905858] [PubMed: 29630852] [CrossRef]

- 190.

- Domenech-Briz V, Romero RG, de Miguel-Montoya I, et al. Results of Nurse Case Management in Primary Heath Care: Bibliographic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Dec;17(24):17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249541. PMID: WOS:000602841900001. Exclusion Code: X7. [PMC free article: PMC7766905] [PubMed: 33419267] [CrossRef]

- 191.

- Donate-Martinez A, Rodenas F, Garces J. Impact of a primary-based telemonitoring programme in HRQOL, satisfaction and usefulness in a sample of older adults with chronic diseases in Valencia (Spain). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016 Jan–Feb;62:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.09.008. PMID: 27432036. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 26446784] [CrossRef]

- 192.

- Doran KM, Vashi AA, Platis S, et al. Navigating the boundaries of emergency department care: addressing the medical and social needs of patients who are homeless. Am J Public Health. 2013 Dec;103 Suppl 2:S355–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2013.301540. PMID: 24148054. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC3969133] [PubMed: 24148054] [CrossRef]

- 193.

- Doupe MB, Palatnick W, Day S, et al. Frequent users of emergency departments: developing standard definitions and defining prominent risk factors. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Jul;60(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.036. PMID: 22221292. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 22305330] [CrossRef]

- 194.

- Dowd BE, Swenson T, Parashuram S, et al. PQRS participation, inappropriate utilization of health care services, and Medicare expenditures. Med Care Res Rev. 2016 Feb;73(1):106–23. doi: 10.1177/1077558715597846. PMID: 27166469. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 26324510] [CrossRef]

- 195.

- Downey LV, Zun LS. Reasons for readmissions: what are the reasons for 90-day readmissions of psychiatric patients from the ED? Am J Emerg Med. 2015 Oct;33(10):1489–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.06.056. PMID: 26206441. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 26164411] [CrossRef]

- 196.

- Dreyfus KS. Adult attachment theory and diabetes mellitus: an examination of healthcare utilization and biopsychosocial health: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2015. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 197.

- Dryden EM, King K, Touw S. Facilitators and Barriers to Successful Engagement in a Complex Care Management Program: Patient and Care Manager Perspectives. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019 May;30(2):789–805. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2019.0056. PMID: WOS:000468495900026. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 31130551] [CrossRef]

- 198.

- Duenas M, Sow S, Poveda C, et al. Engaging the disengaged: outcomes of recruitment and enrollment of high-risk, high-utilizers into an intensive outpatient primary care program for complex care management. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):783–4. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 199.

- DuGoff EH, Boyd C, Anderson G. Complex Patients and Quality of Care in Medicare Advantage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Feb;68(2):395–402. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16236. PMID: 31054588. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 31675101] [CrossRef]

- 200.

- DuGoff EH, Buckingham W, Kind AJ, et al. Targeting high-need beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage: opportunities to address medical and social needs. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2019 Feb 1;2019:1–14. PMID: 29554592. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 30938944]

- 201.

- Durand-Zaleski I. U.S.–France International Meeting on care for high-need, high-cost patients. Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris: Commonwealth Fund; 2015. Exclusion Code: X7.

- 202.

- Duru OK, Harwood J, Moin T, et al. Evaluation of a National Care Coordination Program to Reduce Utilization Among High-cost, High-need Medicaid Beneficiaries With Diabetes. Med Care. 2020 Jun;58 Suppl 6 Suppl 1:S14–s21. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000001315. PMID: 32818784. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC10653047] [PubMed: 32412949] [CrossRef]

- 203.

- Eden E, DeKosky A, Chen LW, et al. High utilizers of condition help: demographic and medical characteristics of patients who repeatedly activate rapid response teams. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):S205–S6. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 204.

- Edwards ST, Saha S, Prentice JC, et al. Preventing hospitalization with Veterans Affairs home-based primary care: which individuals benefit most? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Aug;65(8):1676–83. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14843. PMID: 28410824. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC8284941] [PubMed: 28323324] [CrossRef]

- 205.

- Englander H, Michaels L, Chan B, et al. The care transitions innovation (C-train) for socioeconomically disadvantaged adults, results of a clustered randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:S221–. PMID: CN-01010119. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC4238212] [PubMed: 24913003]

- 206.

- Epstein DH, Preston KL. Does cannabis use predict poor outcome for heroin-dependent patients on maintenance treatment? Past findings and more evidence against. Addiction. 2003 Mar;98(3):269–79. PMID: 12945810. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC2943839] [PubMed: 12603227]

- 207.

- Etemad LR, McCollam PL. Predictors of high-cost managed care patients with acute coronary syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005 Dec;21(12):1977–84. doi: 10.1185/030079905x74970. PMID: 30355286. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 16368049] [CrossRef]

- 208.

- Eton DT, Lee MK, St Sauver JL, et al. Known-groups validity and responsiveness to change of the Patient Experience with Treatment and Self-management (PETS vs. 2.0): a patient-reported measure of treatment burden. Qual Life Res. 2020 Nov;29(11):3143–54. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02546-x. PMID: WOS:000539517700001. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC8012109] [PubMed: 32524346] [CrossRef]

- 209.

- Ettner SL, Frank RG, McGuire TG, et al. Risk adjustment alternatives in paying for behavioral health care under Medicaid. Health Serv Res. 2001 Aug;36(4):793–811. PMID: 14727682. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC1089257] [PubMed: 11508640]

- 210.

- Faresjo A, Grodzinsky E, Foldevi M, et al. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome in primary care appear not to be heavy healthcare utilizers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Mar 15;23(6):807–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02815.x. PMID: 16672680. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 16556183] [CrossRef]

- 211.

- Feinglass J, Norman G, Golden RL, et al. Integrating Social Services and Home-Based Primary Care for High-Risk Patients. Popul Health Manag. 2018 Apr;21(2):96–101. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0026. PMID: 28609187. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 28609187] [CrossRef]

- 212.

- Ferrari S, Galeazzi GM, Mackinnon A, et al. Frequent attenders in primary care: impact of medical, psychiatric and psychosomatic diagnoses. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(5):306–14. doi: 10.1159/000142523. PMID: 16460995. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 18600036] [CrossRef]

- 213.

- Fertel BS, Hart KW, Lindsell CJ, et al. Patients who use multiple EDs: quantifying the degree of overlap between ED populations. West J Emerg Med. 2015 Mar;16(2):229–33. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.1.22838. PMID: 26447915. Exclusion Code: X4. [PMC free article: PMC4380370] [PubMed: 25834661] [CrossRef]

- 214.

- Fertel BS, Podolsky SR, Mark J, et al. Impact of an individual plan of care for frequent and high utilizers in a large healthcare system. Am J Emerg Med. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.02.032. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 30824276] [CrossRef]

- 215.

- Figueroa JF, Joynt Maddox KE, Beaulieu N, et al. Concentration of potentially preventable spending among high-cost Medicare subpopulations: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Nov 21;167(10):706–13. doi: 10.7326/m17-0767. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 29049488] [CrossRef]

- 216.

- Figueroa JF, Lyon Z, Zhou X, et al. Persistence and Drivers of High-Cost Status Among Dual-Eligible Medicare and Medicaid Beneficiaries: An Observational Study. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 16;169(8):528–34. doi: 10.7326/m18-0085. PMID: 30285049. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 30285049] [CrossRef]

- 217.

- Filippi A, Sessa E, Pecchioli S, et al. Homecare for patients with heart failure in Italy. Ital Heart J. 2005 Jul;6(7):573–7. PMID: 15911164. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 16274019]

- 218.

- Finkelstein AN. Health care hotspotting: a randomized controlled trial. Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab. Cooper University Hospital, Camden, New Jersey: 2014. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 219.

- Fiorentino M, Mulles S, Cue L, et al. High Acuity of Postoperative Consults to Emergency General Surgery at an Urban Safety Net Hospital. J Surg Res. 2021 Jan;257:50–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.07.038. PMID: 32008721. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 32818784] [CrossRef]

- 220.

- Fisher HM, McCabe S. Managing chronic conditions for elderly adults: the VNS CHOICE model. Health Care Financ Rev. 2005 Fall;27(1):33–45. PMID: 16205429. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC4194907] [PubMed: 17288076]

- 221.

- Fitzpatrick T, Rosella LC, Calzavara A, et al. Looking Beyond Income and Education: Socioeconomic Status Gradients Among Future High-Cost Users of Health Care. Am J Prev Med. 2015 Aug;49(2):161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.018. PMID: 25748258. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 25960393] [CrossRef]

- 222.

- Flarup L, Moth G, Christensen MB, et al. Chronic-disease patients and their use of out-of-hours primary health care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2014 Jun 9;15:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-114. PMID: 24801269. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC4064509] [PubMed: 24912378] [CrossRef]

- 223.

- Fleishman JA, Cohen JW. Using information on clinical conditions to predict high-cost patients. Health Serv Res. 2010 Apr;45(2):532–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01080.x. PMID: 23740662. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC2838159] [PubMed: 20132341] [CrossRef]

- 224.

- Fleming MD, Shim JK, Yen I, et al. Caring for “Super-utilizers”: Neoliberal Social Assistance in the Safety-net. Med Anthropol Q. 2019 Jun;33(2):173–90. doi: 10.1111/maq.12481. PMID: 30726920. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 30291726] [CrossRef]

- 225.

- Fleury MJ, Grenier G, Bamvita JM, et al. Professional service utilisation among patients with severe mental disorders. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010 May 27;10:141. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-141. PMID: 20078404. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC2896947] [PubMed: 20507597] [CrossRef]

- 226.

- Flottemesch TJ, Anderson LH, Solberg LI, et al. Patient-centered medical home cost reductions limited to complex patients. Am J Manag Care. 2012 Nov;18(11):677–86. PMID: 22961756. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 23198711]

- 227.

- Flowers A, Shade K. Evaluation of a Multidisciplinary Care Coordination Program for Frequent Users of the Emergency Department. Prof Case Manag. 2019 Sep/Oct;24(5):230–9. doi: 10.1097/ncm.0000000000000368. PMID: 29471360. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 31373952] [CrossRef]

- 228.

- Flynn P, Ridgeway J, Wieland M, et al. Primary care utilization and mental health diagnoses among adult patients requiring interpreters: a retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):386–91. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2159-5. PMID: 85715044. Exclusion Code: X4. [PMC free article: PMC3579974] [PubMed: 22782282] [CrossRef]

- 229.

- Foebel AD, Hirdes JP, Heckman GA, et al. A profile of older community-dwelling home care clients with heart failure in Ontario. Chronic Dis Can. 2011 Mar;31(2):49–57. PMID: 21343403. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 21466754]

- 230.

- Fondow M, Schreiter EZ, Thomas C, et al. Initial examination of characteristics of patients who are high utilizers of an established primary care behavioral health consultation service. Families Systems & Health. 2017 Jun;35(2):184–92. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000266. PMID: WOS:000403442700009. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 28617019] [CrossRef]

- 231.

- Foo KM, Sundram M, Legido-Quigley H. Facilitators and barriers of managing patients with multiple chronic conditions in the community: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2020 Feb;20(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8375-8. PMID: WOS:000519946500003. Exclusion Code: X6. [PMC free article: PMC7045577] [PubMed: 32106838] [CrossRef]

- 232.

- Ford JD, Trestman RL, Steinberg K, et al. Prospective association of anxiety, depressive, and addictive disorders with high utilization of primary, specialty and emergency medical care. Soc Sci Med. 2004 Jun;58(11):2145–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.017. PMID: 15323413. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 15047073] [CrossRef]

- 233.

- Ford JD, Trestman RL, Tennen H, et al. Relationship of anxiety, depression and alcohol use disorders to persistent high utilization and potentially problematic under-utilization of primary medical care. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Oct;61(7):1618–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.017. PMID: WOS:000231024400023. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 16005791] [CrossRef]

- 234.

- Fordyce MA, Doescher MP, Skillman SM. The aging of the rural primary care physician workforce: will some locations be more affected than others? [Seattle, WA]: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center; 2013. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 235.

- Fortin M, Cao Z, Fleury MJ. A typology of satisfaction with mental health services based on Andersen’s behavioral model. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018 Jun;53(6):587–95. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1498-x. PMID: 27936849. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 29450599] [CrossRef]

- 236.

- Franco RA, Ashwathnarayan R, Deshpandee A, et al. The high prevalence of restless legs syndrome symptoms in liver disease in an academic-based hepatology practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008 Feb 15;4(1):45–9. PMID: 18399957. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC2276829] [PubMed: 18350962]

- 237.

- Fraze TK, Beidler LB, Briggs ADM, et al. Translating Evidence into Practice: ACOs’ Use of Care Plans for Patients with Complex Health Needs. JGIM: Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2021;36(1):147–53. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06122-4. PMID: 148469973. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC7858720] [PubMed: 33006083] [CrossRef]

- 238.

- Fraze TK, Briggs ADM, Whitcomb EK, et al. Role of Nurse Practitioners in Caring for Patients With Complex Health Needs. Med Care. 2020 Oct;58(10):853–60. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000001364. PMID: WOS:000576505000002. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC7552908] [PubMed: 32925414] [CrossRef]

- 239.

- Fruhauf J, Schwantzer G, Ambros-Rudolph CM, et al. Pilot study using teledermatology to manage high-need patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2010 Feb;146(2):200–1. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.375. PMID: 20825136. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 20157037] [CrossRef]

- 240.

- Fuda KK, Immekus R. Frequent users of Massachusetts emergency departments: a statewide analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2006 Jul;48(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.001. PMID: 19487595. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 16781915] [CrossRef]

- 241.

- Galbraith AA, Meyers DJ, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Long-Term Impact of a Postdischarge Community Health Worker Intervention on Health Care Costs in a Safety-Net System. Health Serv Res. 2017 Dec;52(6):2061–78. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12790. PMID: 29130267. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5682134] [PubMed: 29130267] [CrossRef]

- 242.

- Gallagher NA, Fox D, Dawson C, et al. Improving care transitions: complex high-utilizing patient experiences guide reform. Am J Manag Care. 2017 Oct 1;23(10):e347–e52. PMID: 28829516. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 29087639]

- 243.

- Gallagher S. Exploring supportive housing’s impact on health and health care quality among high-cost, high-need populations. Corporation for Supportive Housing 2017. https://www

.commonwealthfund .org/grants/exploring-supportive-housings-impact-health-and-health-care-quality-among-high-cost-high. Exclusion Code: X7. - 244.

- Garg T, Young AJ, Kost KA, et al. Burden of multiple chronic conditions among patients with urological cancer. J Urol. 2018 Feb;199(2):543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.08.005. PMID: 29473945. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 28789948] [CrossRef]

- 245.

- Gastal FL, Andreoli SB, Quintana MI, et al. Predicting the revolving door phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, affective disorders and non-organic psychoses. Rev Saude Publica. 2000 Jun;34(3):280–5. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102000000300011. PMID: 10883718. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 10920451] [CrossRef]

- 246.

- Geisz M. A coalition creates a citywide care management system. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Princeton, NJ: 2014. https://www

.rwjf.org /en/library/research /2011/01/a-coalition-creates-a-citywide-care-management-system-.html. Exclusion Code: X1. - 247.

- Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000 Feb;34(6):1273–302. PMID: 10654830. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC1089079] [PubMed: 10654830]

- 248.

- Geurts J, Palatnick W, Strome T, et al. Frequent users of an inner-city emergency department. Cjem. 2012 Sep;14(5):306–13. PMID: 21491293. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 22967698]

- 249.

- Giannouchos TV, Kum HC, Foster MJ, et al. Characteristics and predictors of adult frequent emergency department users in the United States: A systematic literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019 Jun;25(3):420–33. doi: 10.1111/jep.13137. PMID: 32589150. Exclusion Code: X7. [PubMed: 31044484] [CrossRef]

- 250.

- Giannouchos TV, Washburn DJ, Kum HC, et al. Predictors of Multiple Emergency Department Utilization Among Frequent Emergency Department Users in 3 States. Med Care. 2020 Feb;58(2):137–45. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000001228. PMID: 31373550. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 31651740] [CrossRef]

- 251.

- Gingold DB, Pierre-Mathieu R, Cole B, et al. Impact of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion on emergency department high utilizers with ambulatory care sensitive conditions: A cross-sectional study. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 May;35(5):737–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.01.014. PMID: 27008540. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 28110978] [CrossRef]

- 252.

- Glick M. Systematic approach for treating the medically complex dental patient. Alpha Omegan. 2001 Jul–Aug;94(2):40–3. PMID: 11407062. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 11480187]

- 253.

- Goldstein KM, Zullig LL, Dedert EA, et al. Telehealth interventions designed for women: an evidence map. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(12):2191–200. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4655-8. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6258612] [PubMed: 30284173] [CrossRef]

- 254.

- Goodell S, Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Princeton, NJ: 2009. https://www

.rwjf.org /en/library/research /2009/12/care-management-of-patients-with-complex-health-care-needs.html. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 22052205] - 255.

- Goodwin A, Henschen B, Nichols N, et al. Systematic review of interventions targeting high-utilizers of inpatient resources. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):352. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 256.

- Goodwin A, Henschen BL, O’Dwyer LC, et al. Interventions for frequently hospitalized patients and their effect on outcomes: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):853–9. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3090. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 30379144] [CrossRef]

- 257.

- Gore S, Lind A, Somers SA. Profiles of state innovation: roadmap for improving systems of care for dual eligibles. Hamilton, N.J.: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.; 2010. Exclusion Code: X1.

- 258.

- Gottlieb LM, Garcia K, Wing H, et al. Clinical interventions addressing nonmedical health determinants in Medicaid managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2016 May;22(5):370–6. PMID: 27266438. Exclusion Code: X7. [PubMed: 27266438]

- 259.

- Grazioli VS, Moullin JC, Kasztura M, et al. Implementing a case management intervention for frequent users of the emergency department (I-CaM): an effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Jan 11;19(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3852-9. PMID: 30212929. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC6330435] [PubMed: 30634955] [CrossRef]

- 260.

- Greenberg P, Corey-Lisle PK, Birnbaum H, et al. Economic implications of treatment-resistant depression among employees. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(6):363–73. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422060-00003. PMID: 12716790. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 15099122] [CrossRef]

- 261.

- Gregori D, Petrinco M, Barbati G, et al. Extreme regression models for characterizing high-cost patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009 Feb;15(1):164–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.00976.x. PMID: 23055291. Exclusion Code: X9. [PubMed: 19239597] [CrossRef]

- 262.

- Grembowski D, Schaefer J, Johnson KE, et al. A conceptual model of the role of complexity in the care of patients with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care. 2014 Mar;52 Suppl 3:S7–s14. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000045. PMID: 24561762. Exclusion Code: X4. [PubMed: 24561762] [CrossRef]

- 263.

- Griffin JL, Yersin M, Baggio S, et al. Characteristics and predictors of mortality among frequent users of an emergency department in Switzerland. Eur J Emerg Med. 2018 Apr;25(2):140–6. doi: 10.1097/mej.0000000000000425. PMID: 30358755. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 27749377] [CrossRef]

- 264.

- Grinspan ZM, Shapiro JS, Abramson EL, et al. Predicting frequent ED use by people with epilepsy with health information exchange data. Neurology. 2015 Sep 22;85(12):1031–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000001944. PMID: 26152468. Exclusion Code: X4. [PMC free article: PMC4603600] [PubMed: 26311752] [CrossRef]

- 265.

- Grover CA, Crawford E, Close RJ. The efficacy of case management on emergency department frequent users: an eight-year observational study. J Emerg Med. 2016 Nov;51(5):595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.002. PMID: 26784515. Exclusion Code: X1. [PubMed: 27595372] [CrossRef]

- 266.

- Grover CA, Sughair J, Stoopes S, et al. Case management reduces length of stay, charges, and testing in emergency department frequent users. West J Emerg Med. 2018 Mar;19(2):238–44. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.9.34710. PMID: 30523008. Exclusion Code: X1. [PMC free article: PMC5851494] [PubMed: 29560049] [CrossRef]

- 267.