NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (UK). Addendum to Haematological Cancers: improving outcomes (update). London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2016 May.

The role of integrated diagnostic reporting in the diagnosis of haematological malignancies

Review Question

Should integrated diagnostic reporting (via Specialist Integrated Haematological Malignancy Diagnostic Services [SIHMDS]) replace local reporting in the diagnosis of haematological malignancies?

What are the effective ways of delivering integrated diagnostic reports (for example, co-located or networked) in the diagnosis of haematological malignancies?

Background

The main driver for this recommendation in the improving outcomes guidance and subsequent 2012 revision (agreed by the National Cancer Action Team and the RCPath) was evidence of a significant misdiagnosis rate for haematological malignancies (5-15%) sometimes with major clinical consequences (Clarke et al., 2004; LaCasce et al., 2008; Lester et al., 2003; Proctor et al., 2011). This type of error can be difficult to detect after a patient has been treated and therefore a premium must be placed on being able to demonstrate that a diagnosis is correct and supported by strong evidence across several independent investigative modalities. This approach is intrinsic to the way that disease entities are defined in the World Health Organisation (WHO) classification and is common to all haematological malignancies.

The availability of the necessary investigations varies across the country. To be effective this multi-modality approach to diagnostic quality assurance requires a systematic approach to the investigation of specimens and a clear process to interpret and integrate the results obtained (via integrated diagnostic reporting), most crucially to identify inconsistencies between the results obtained by different investigative techniques. This is most effectively delivered within an integrated diagnostic service able to provide the full range of diagnostic techniques required and to provide a report to the end users that integrates these results into a single diagnostic assessment; this was the rationale behind the current guidance (Ireland et al, 2011). A very important subsidiary consideration is that diagnostic techniques are rapidly evolving and these developing techniques need to be reflected in laboratory organization. The efficient delivery of evolving modern diagnostic approaches, such as molecular genetics and flow cytometry, potentially across a range of specialities with the required quality and economy of scale needs to be balanced against the requirements of specialised integrated reporting, which, on a practical level, are easiest to achieve within a fully integrated laboratory or other closely located laboratory configuration. This is because the diagnosis, classification and prognostic assessment of these conditions requires integration of multiple diagnostic techniques and high levels of ascertainment and data quality can only realistically be achieved in an infrastructure which facilitates routine, direct interaction between component laboratory professionals.

High quality data on diagnosis, treatment and outcome data on cancer patients is a key objective of the NHS. Data quality in haematology has long been a major problem with widely differing levels of ascertainment between regions and the ability to report data in only the broadest categories of limited clinical utility. A greater implementation and standardisation of SIHMDS reporting should improve the quality of data in haemato-oncology and contribute to NHS goals. In addition, the integrated delivery of modern diagnostics in haemato-oncology is a highly active area of research and development that the NHS is uniquely placed to make an internationally competitive contribution.

However, there are a number of other important considerations for example, the availability of suitably trained staff (pathologists, clinical and biomedical scientists) is limited and constrains the number of centres able to offer this service. To ensure rapid diagnosis and to conserve diagnostic material (which in the case of needle core biopsies, may be sparse) it is important that specimens from patients suspected of having a haematological malignancy are referred directly to the specialist laboratory. This raises two problems, which have proved a significant obstacle to implementing this guidance. It is not always possible to identify specimens that require referral from the patient's clinical features alone and triage by local pathologist and haematologists is important. Concern is also expressed frequently that this means that local pathology staff will become deskilled and more broadly that referral of specialist work of this type undermines the viability and job satisfaction of local hospital laboratories. Although previous consensus recommendations have been made for minimum catchment populations for the delivery of SIHMDS (NCAT 2012), there is no evidence to support such thresholds. Delivery of SIHMDS may be influenced by regional configurations of clinical haematology and oncology services, including MDTs and academic networks, along with broader geographical considerations such as regional infrastructure and transport flows. Although Cancer Networks are no longer in operation, their effect may persist in NHS cancer services in regional working relationships and service delivery.

In recent multicentre UK studies, early mortality following AML induction chemotherapy has been reported as up to 6% and 9% at 30 days and 10% and 15% at 60 days in younger and older patients respectively (Burnett et al, 2015; Burnett et al, 2012).

Reported induction mortality is also substantial in ALL; 4% in patients <55 and 18% in patients over 55 years (Sive et al, 2012). Early mortality in ALL is not improved with the introduction of modern drugs, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Philadelphia positive disease (Fielding AK et al, 2014). Recent data confirm a 2.2% induction death rate in 16-25 year olds treated on paediatric protocols. In 25 – 60 year olds treated on the current NCRI UKALL 14 type schedule, the induction death rate in UKALL 14 currently is 8.5% (personal communication, Dr Clare Rowntree).

Question in PICO format

| PICO Table 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes |

| Adults and young people (16 years and older) and children presenting with suspected haematological malignancies | Integrated diagnostic reporting via the specialist integrated haematological malignancy diagnostic services | Any other reporting |

|

| PICO Table 2 | |||

| Population | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes |

| Adults and young people (16 years and older) and children presenting with suspected haematological malignancies | Co-located integrated diagnostic reporting Networked integrated diagnostic reporting | Each Other |

|

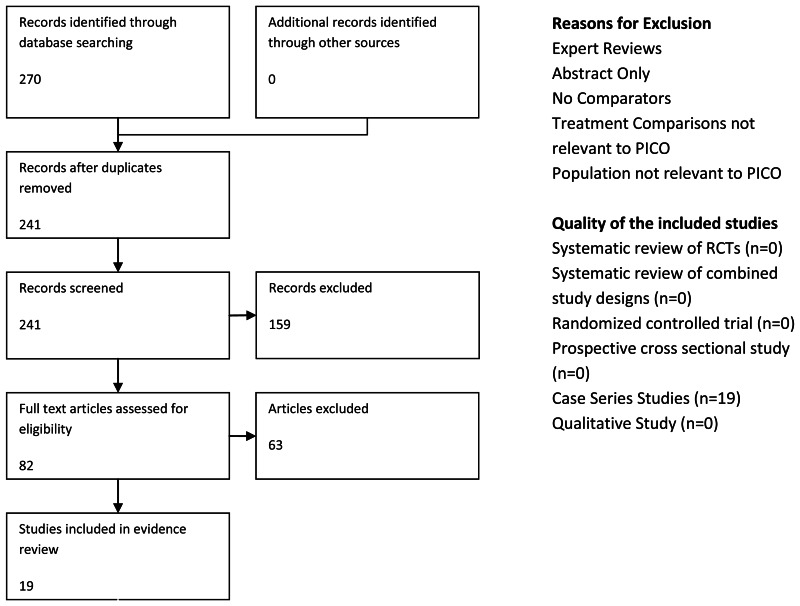

Searching and Screening

| Searches: | |

|---|---|

| Can we apply date limits to the search | 2000 Rationale: IOG guideline (2003) supporting evidence of integrated services published since 2000 |

| Are there any study design filters to be used (RCT, systematic review, diagnostic test). | RCT's not likely to be available Case series with one intervention or case reports will not be included due to no comparison to the reference standard/ other interventions. |

| List useful search terms. | None identified |

Search Results

| Database name | Dates Covered | No of references found | No of references retrieved | Finish date of search |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medline | 1996-Apr 2015 | 1591 | 74 | 14/042015 |

| Premedline | Apr 10 2015 | 133 | 4 | 13/04/2015 |

| Embase | 1996-Apr 2015 | 3932 | 113 | 15/04/2015 |

| Cochrane Library | Issue 4, Apr 2015 | 505 | 0 | 20/04/2015 |

| Web of Science (SCI & SSCI) and ISI Proceedings | 1900-2015 | 3452 | 62 | 22/04/2015 |

| HMIC | All | 4 | 1 | 2004/2015 |

| PscyInfo | 1806-Apr 2015 | 22 | 1 | 20/04/2015 |

| CINAHL | 1118 | 13 | 28/04/2015 | |

| Joanna Briggs Institute EBP database | Current to Apr 22 2015 | 2 | 0 | 22/04/2015 |

| OpenGrey | 355 | 1 | 22/04/2015 | |

| HMRN (Haematological Malignancy Research Network) | 49 | 2 | 28/04/2015 | |

| British Committee for Standards in Haematology | 43 | 11 | 29/04/2015 |

Total References retrieved (after initial sift and de-duplication): 270

Medline search strategy (This search strategy is adapted to each database)

- exp Hematologic Neoplasms/

- ((haematolog* or hematolog* or blood or red cell* or white cell* or lymph* or marrow or platelet*) adj1 (cancer* or neoplas* or oncolog* or malignan* or tumo?r* or carcinoma* or adenocarcinoma* or sarcoma*)).tw.

- exp Lymphoma/

- lymphoma*.tw.

- (lymph* adj1 (cancer* or neopla* or oncolog* or malignan* or tumo?r*)).tw.

- hodgkin*.tw.

- lymphogranulomato*.tw.

- exp Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin/

- (nonhodgkin* or non-hodgkin*).tw.

- lymphosarcom*.tw.

- reticulosarcom*.tw.

- Burkitt Lymphoma/

- (burkitt* adj (lymphom* or tumo?r* or cancer* or neoplas* or malign*)).tw.

- brill-symmer*.tw.

- Sezary Syndrome/

- sezary.tw.

- exp Leukemia/

- (leuk?em* or AML or CLL or CML).tw.

- exp Neoplasms, Plasma Cell/

- myelom*.tw.

- (myelo* adj (cancer* or neopla* or oncolog* or malignan* or tumo?r*)).tw.

- kahler*.tw.

- Plasmacytoma/

- (plasm?cytom* or plasm?zytom*).tw.

- (plasma cell* adj3 (cancer* or neoplas* or oncolog* or malignan* or tumo?r* or carcinoma* or adenocarcinoma*)).tw.

- Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia/

- waldenstrom.tw.

- exp Bone Marrow Diseases/

- exp Anemia, Aplastic/

- (aplast* adj an?em*).tw.

- exp Myelodysplastic-Myeloproliferative Diseases/

- exp Myeloproliferative Disorders/

- exp Myelodysplastic Syndromes/

- exp Thrombocytopenia/

- (thrombocytop?eni* or thrombocyth?emi* or poly-cyth?emi* or polycyth?emi* or myelofibros or myelodysplas* or myeloproliferat* or dysmyelopoietic or haematopoetic or hematopoetic).tw.

- exp Anemia, Refractory/

- (refractory adj an?em*).tw.

- (refractory adj cytop?en*).tw.

- Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance/

- (monoclonal adj gammopath*).tw.

- (monoclonal adj immunoglobulin?emia).tw.

- MGUS.tw.

- ((oncohaematolog* or oncohematolog*) adj2 (disorder* or disease* or syndrome*)).tw.

- or/1-42

- limit 44 to yr=“2000 - 2015”

- Clinical Laboratory Services/

- Clinical Laboratory Information Systems/

- Diagnostic Services/

- (laborator* adj2 (service* or report*)).tw.

- (laborator* adj1 (integrat* or central* or co-locat* or local* or region* or district* or communit* or hospital* or network* or specialis*)).tw.

- (diagnos* adj2 (service* or report*)).tw.

- (diagnos* adj1 (integrat* or central* or local* or region* or district* or communit* or hospital* or network*)).tw.

- Pathology Department, Hospital/

- Laboratories, Hospital/

- Diagnostic Errors/

- (diagnos* adj discrepanc*).tw.

- (expert review* or expert patholog* review*).tw.

- second review.tw.

- central* review.tw.

- ((haematopatholog* or hematopatholog* haematolog* or hematolog* or patholog* or histopatholog* or cytopatholog*) adj2 (service* or report*)).tw.

- ((haematopatholog* or hematopatholog* haematolog* or hematolog*or patholog* or histopatholog* or cytopatholog*) adj1 (integrat* or central* or co-locat* or local* or region* or communit* or hospital* or network* or specialis*)).tw.

- inter-laborator*.tw.

- SIHMDS.tw.

- exp laboratories/

- Hospital Information Systems/

- or/46-65

- 45 and 66

Study Quality

A short checklist of relevant questions was developed to assess the quality of the included studies and from this it was judged that the included evidence was of low quality overall as all identified studies were retrospective case series studies and none of the included studies directly compared integrated diagnostic services with other forms of diagnostic services.

All studies included relevant populations with either general haematology patients or specific haematology subtypes such as lymphoma patients included in the individual studies.

Identified studies broadly compared the rates of discordance in diagnosis of haematological malignancies between initial diagnosis and review diagnosis by expert pathologists, sometimes based in a specialist laboratory, though it was unclear in the individual studies whether the expert pathologists were blinded to the initial diagnosis therefore there is a high risk of bias based on the potential lack of blinding.

The outcomes reported in each of the studies were not specifically those listed in the PICO table, however the outcomes reported (e.g. diagnostic discordance, change in management, survival) were considered to be of some use in informing discussions.

Overall, the quality of the evidence for this topic was considered to be low quality for all outcomes.

| Study | Study Type/Setting | Aim | Population | Intervention | Comaprison | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bowen et al (2014) | Retrospective Study | To determine the rate of revised diagnosis and subsequent impact on therapy following a second review | N=1010 | Second Review Diagnosis | Primary referral diagnosis |

|

| 2 | Chang et al (2014) | Retrospective Study | To review the final diagnoses made by general pathologists and analyse the discrepancies between referral and review diagnosis | N=395 | Expert Review | Initial Diagnosis |

|

| 3 | Engel Nitz et al (2014) | Retrospective Study Laboratory | To compare diagnostic changes, patterns of additional testing, treatment decisions and health care costs for patients with suspected haematological malignancies/conditions whose diagnostic tests were managed by specialty haematology laboratories and other commercial laboratories. | N=24,664 patients Genoptix N=1,387 Large Labs N=4,162 Other Controls (community hospital labs) N=19,115 | Initial interim diagnosis | Final Diagnosis |

|

| 4 | Gundlapalli et al (2009) | Survey | To address the hypotheses that clinical providers perceive composite laboratory reports to be important for the care of complex patients and that such reports can be generated using laboratory informatics methods | N=10 clinical staff | Survery and interview | None |

|

| 5 | Herrera et al (2014) | Retrospective Study | To evaluate the rate of diagnostic concordance between referring centre diagnoses and expert haematology review for 4 subtypes of T-cell lymphoma | N=89 | Review of primary diagnosis at an NCCN centrte | Primary diagnosis at a referring centre |

|

| 6 | Irving et al (2009) | Report | To show that the standardised protocol has high sensitivity and technical applicability, has good concordance with the gold standard molecular based analysis and is highly reproducible between laboratories across different instrument platforms. | No details | Standardised protocol for flow cytometry | Gold standard molecular technique |

|

| 7 | LaCasce et al (2005) | Retrospective Study | To determine the rate of discordance for 5 common B-cell NHL diagnoses in five tertiary centres participating in a large national lymphoma database The determine whether additional information was obtained at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) centre To estimate the likely impact of a change in diagnosis on treatment | N=928 | Pathologic diagnosis from the referral centre was compared with the final WHO diagnosis at the NCCN centres Etiology of the discordance was investigated along with the potential impact on treatment. A random sample of concordant cases (10%) were also reviewed | No Details |

|

| 8 | Lester et al (2003) | Retospective Study | To establish the impact of the All Wales Lymphoma Panel review on clinical management decisions | N=99 | Cases submitted for central review | Actual management plan received by the patient |

|

| 9 | Matasar et al (2012) | Retrospective Study Laboratory Setting | To test the hypothesis that increased familiarity with the WHO classification of haematological malignancies is associated with a change in frequency of major diagnostic revision at pathology review. | N=719 | Diagnosis and review in 2001 using the WHO classification of haematological malignancies | Diagnosis and review in 2006 using the WHO classification of haematological malignancies |

|

| 10 | Norbert-Dworzak et al (2008) | Prospective Review | To investigate whether flow cytometric assessment of minimal residual disease can be reliably standardised for multi-centric application | N=413 patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Centre 1=110, Centre 2=88, Centre 3=61, Centre 4=154) N=395 patients with blood and bone marrow samples received at diagnosis and from follow-up during induction treatment: PB at day 8, 15, 22, and 33; BM at day 15, 33 and 78). | Flow Cytometry according to a standard protocol | Results from each centre following standard protocol |

|

| 11 | Norgaard et al (2005) | Retrospective Study | To examine the data quality and quantifying the impact of any misclassification of the diagnoses on the survival estimates | N=1159 | Danish Cancer Registry (DCR) | North Jutland Hospital Discharge Registry |

|

| 12 | Proctor et al (2011) | Retrospective Study | A large scale assessment of expert central review in a UK regional cancer network and the impact of discordant diagnoses on patient management as well as the financial and educational implications of providing a centralised service. | N=1949 | Expert Review | Initial Diagnosis |

|

| 13 | Rane et al (2014) | Retrospective Study | To evaluate the ability and interobserver variability of pathologists with varying levels of experience and with an interest in lymphomas to diagnose Burkitt Lymphoma in a resource limited set up. | N=25 | Consensus Diagnosis | Initial Independent Assessment |

|

| 14 | Siebert et al (2001) | Retropsective Study | To compare diagnoses made at a community and an academic centre to evaluate the reproducibility of the revised European-American Classification | N=188 | Review of community hospital assessments at an academic centre | lymphoid neoplasms subtyped according to revised European-American classification criteria at a community hospital |

|

| 15 | Stevens et al (2012) | Retrospective Study | To observe concordance and discrepancies between local findings and the specialist opinion. | N=125 | Central Review | Regional/Community Hospital Review |

|

| 16 | Strobbe et al (2014) | Retrospective Study | To investigate whether implementation of an expert panel led to better quality of initial diagnoses by comparing the rate of discordant diagnoses after the panel was established compared with discordance rate 5 years later To evaluate whether lymphoma types with high discordance rate could be identified | N=161 referred to the expert panel N=183 reviewed at a later date | Expert Panel review | Initial Diagnosis |

|

| 17 | Van Blerk et al (2003) | Retrospective Study | To report first experiences from Belgian national external quality assessment scheme (EQAS) | N=17 | External quality assessment review | N/A |

|

| 18 | Van de Schans et al (2013) | Retrospective Study | To evaluate the value of an expert pathology panel and report discordance rates between the diagnosis of initial pathologists and the expert panel and the effect on survival | N=344 | Expert review of diagnosis | Initial Diagnosis |

|

| 19 | Zhang et al (2007) | Retrospective Study | To compare similarities and differences in results from participating laboratories and to identify variables which could potentially affect test results to discern variables important in test standardisation | N=38 laboratories | Quantitative testing for BCR-ABL1 | Results from different participating laboratories |

|

Evidence Statements

Low quality evidence from a total of nine retrospective studies of either haematology or lymphoma populations, two of which were UK based (Bowen et al, 2014; Chang et al, 2014; Herrera et al, 2014; LaCasce et al, 2005; Lester et al, 2003; Proctor et al, 2011; Siebert et al, 2001, Stevens et al, 2012, and van de Schans et al, 2013). The discordance rates between initial haematological pathological diagnoses and expert review ranged from 6%-60%. Revision of one type of lymphoma to another type was the most common source of discordance ,ranging from 6.5%-23% (2 studies; Bowen et al 2014; Chang et al, 2014).

Low quality evidence for major discrepancies, leading to a change in treatment or management was recorded in four retrospective studies (Chang et al, 2014; Lester et al; 2003; Matasar et al, 2012 and Stevens et al, 2012) with rate of discordance between an initial diagnosis and review diagnosis ranging from 17.8% to 55%.

Low quality evidence from one retrospective study (Engel-Nitz et al, 2014) which compared diagnostic outcomes between specialist haematology laboratories and other commercial laboratories and reported that patients in the specialist laboratory cohort were more likely to undergo more complex diagnostic testing with 26% of patients undergoing molecular diagnostics compared with 9.3% in community based hospital laboratories. Patients in the specialist laboratory cohort were 23% more likely to reach a final diagnosis within a 30 day testing period when compared with community based hospital laboratories.

Low quality evidence from one retrospective study compared a national registry of haematological malignancies with a hospital discharge registry to investigate the data quality and the impact of misclassification on survival in haematology patients (Norgaard et al, 2005). It reported the overall data completeness was 91.5% [95% CI, 89.6%-93.1%] and that the survival of patients registered in the hospital discharge registry was about 20% lower and about 10% lower for patients registered in the national registry when compared with patients registered in both.

Low quality evidence from a single retrospective study evaluating the value of expert pathology review (van de Schans et al, 2013) reported no statistically significant difference in 5-year survival between patients with a concordant diagnosis compared to those with a discordant diagnosis (48% [95% CI, 42%-53%] versus 53% [95% CI, 39%-67%]).

Low quality evidence from a retrospective study including 25 cases of Burkitt Lymphoma reviewed by 10 pathologists (Rane et al) reported a poor rate of concordance between the pathologists for independent diagnosis (κ0.168, SE±0.018) and a direct correlation between level of experience and diagnosis.Expert lymphoma pathologists showed marginally higher concordance rates and general pathologists the lowest (κ0.373 versus κ0.138). For consensus diagnosis the level of agreement between pathologists for revised diagnosis was very high (κ0.835, SE±0.021) and revision of diagnosis was highest among general pathologists. The concordance of independent diagnosis and consensus diagnosis was low (κ=0.259, SE±0.039; median=0.207; range=0.131-0.667) and increased with increasing experience of diagnosing lymphoma.

Low quality evidence from a retrospective study including 25 cases of Burkitt Lymphoma reviewed by 10 pathologists (Rane et al) reported that expert lymphoma pathologists were significantly more likely to make a correct diagnosis compared with both pathologists with experience (OR=3.14; p=0.012) and general pathologists (OR=5.3; p=0.00032).

Low quality evidence from two retrospective studies (Matasar et al 2012 and Strobbe et al, 2014) showed that the rates of discordance between initial and review diagnoses were found to have dropped between 2001 and 2005, but with no statistically significant difference. Matasar et al, 2012 reported a drop in major revision rates for haematological malignancies from 17.8% to 16.4% (p=0.6) as familiarity with the WHO classification system increased and Strobbe et al, 2014 reported a drop in discordance rate of lymphoma diagnoses from 14% to 9% (p=0.06) following the setting up of an expert lymphoma review panel.

Low quality evidence from two retrospective studies (Irving et al, 2009 and Norbert-Dworzak et al, 2008) reported that interlaboratory agreement was high for the use of a standardised protocol for flow cytometry (correlation coefficient ranged from 0.97-0.99 for observed versus expected values)

Low quality evidence from a survey of 10 clinical staff involved in a myeloma program (Gundlapalli et al, 2009) reported that clinic staff would be in favour of a single diagnostic report with the ability to view serial changes in key biomarkers and also supported the idea of providing a composite report directly to the patient.

References

- Bowen JM, et al. Lymphoma diagnosis at an academic centre: Rate of revision and impact on patient care. British Journal Haematology. 2014;166(2):202–8. [PubMed: 24697285]

- Burnett AK, et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy improves survival in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:3924–31. [PubMed: 22851554]

- Burnett AK, et al. A randomized comparison of daunorubicin 90 mg/m2 vs 60 mg/m2 in AML induction: results from the UK NCRI AML17 trial in 1206 patients. Blood. 2015;125(25):3878–85. [PMC free article: PMC4505010] [PubMed: 25833957]

- Chang C. Hematopathologic discrepancies between referral and review diagnoses: A gap between general pathologists and hematopathologists. Leukaemia and Lymphoma. 2014;55(5):1023–30. [PubMed: 23927394]

- Engel-Nitz, et al. Diagnostic testing managed by haematopathology specialty and other laboratories: costs and patient diagnostic outcomes. BMC Clinical Pathology. 2014;14:17. [PMC free article: PMC4016629] [PubMed: 24817828]

- Fielding AK, et al. UKALLXII/ECOG2993: addition of imatinib to a standard treatment regimen enhances long-term outcomes in Philadelphia positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:843–50. [PMC free article: PMC3916877] [PubMed: 24277073]

- Gundlapalli, et al. Composite patient reports: a laboratory informatics perspective and pilot project for personalized medicine and translational research. Summit on Translational Bioinformatics. 2009:39–43. [PMC free article: PMC3041581] [PubMed: 21347168]

- Herrera AF, Herrera AF. Comparison of referring and final pathology for patients with T-cell lymphoma in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cancer. 2014;120(13):1993–9. [PMC free article: PMC4130379] [PubMed: 24706502]

- Ireland R, et al. Haematological malignancies: the rationale for integrated haematopathology services, key elements of organization and wider contribution to patient care. Histopathology. 2011;58(1):145–54. [PubMed: 21261689]

- Irving J, et al. Establishment and validation of a standard protocol for the detection of minimal residual disease in B lineage childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia by flow cytometry in a multi-center setting. Haematologica. 2009;94(6):870–4. [PMC free article: PMC2688581] [PubMed: 19377076]

- LaCasce A, et al. Potential impact of pathologic review on therapy in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL): Analysis from the national comprehensive cancer network (NCCN) NHL outcomes project. Blood. 2005;106(11):789A.

- Lester JF, et al. The clinical impact of expert pathological review on lymphoma management: a regional experience. British Journal of Haematology. 2003;123(3):463–8. [PubMed: 14617006]

- Matasar, et al. Expert Second Opinion Pathology Review of Lymphoma in the Era of the World Health Organisation Classification. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23:159–166. [PubMed: 21415238]

- Matthey F, et al. Facilities for the Treatment of Adults with Haematological Malignancies – ‘Levels of Care’ BCSH Haemato-Oncology Task Force. 2009 [PubMed: 20423565]

- National Cancer Action Team. Additional Best Practice Commissioning Guidance For developing Haematology Diagnostic Services. 2012. Gateway Number: 17241.

- Norbert-Dworzak, et al. Standardisation of Flow Cytometric Minimal Residual Disease Evaluation in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: Multicentric Assessment is Feasible. Cytometry Part B (Clinical Cytometry). 2008;74B:331–340. [PubMed: 18548617]

- Norgaard M. The data quality of haematological malignancy ICD-10 diagnoses in a population-based hospital discharge registry. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2005;14(3):201–6. [PubMed: 15901987]

- Proctor IEM. Importance of expert central review in the diagnosis of lymphoid malignancies in a regional cancer network. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(11):1431–5. [PubMed: 21343555]

- Rane SU, et al. Interobserver variation is a significant limitation in the diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma. Indian journal of medical and paediatric oncology : official journal of Indian Society of Medical & Paediatric Oncology. 2014;35(1):44–53. [PMC free article: PMC4080663] [PubMed: 25006284]

- Siebert JD, et al. Comparison of lymphoid neoplasm classification - A blinded study between a community and an academic setting. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2001;115(5):650–5. [PubMed: 11345827]

- Sive J, et al. Outcomes In Older Adults with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL): Results From the International MRC UKALL XII/ECOG2993 Trial. British Journal of Haematology. 2012;157(4):463–71. [PMC free article: PMC4188419] [PubMed: 22409379]

- Stevens WBC. Centralised multidisciplinary re-evaluation of diagnostic procedures in patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23(10):2676–81. [PubMed: 22776707]

- Strobbe L, Strobbe L, van der Schans S. Evaluation of a panel of expert pathologists: review of the diagnosis and histological classification of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas in a population-based cancer registry. Leukaemia and Lymphoma. 2014;55(5):1018–22. [PubMed: 23885798]

- Van Blerk M, et al. National external quality assessment scheme for lymphocyte immunophenotyping in Belgium. Clinical Chemistry & Laboratory Medicine. 2003;41(3):323–30. [PubMed: 12705342]

- van de Schans SAM, et al. Diagnosing and classifying malignant lymphomas is improved by referring cases to a panel of expert pathologists. Journal of Hematopathology. 2013;6(4):179–85.

- Zhang T, et al. Inter-laboratory comparison of chronic myeloid leukaemia minimal residual disease monitoring: summary and recommendations. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2007;9(4):421–30. [PMC free article: PMC1975095] [PubMed: 17690211]

Evidence Tables

Download PDF (743K)

Excluded Studies

| Reference List | Comment |

|---|---|

| Burger GT, Van Ginneken AM. Computer-based diagnostic support systems in histopathology: what should they do? Studies in Health Technology & Informatics 2001;84(Pt 2):1120-4. | This paper does not relate to haematology |

| Cook IS, Cook IS. Referrals for second opinion in surgical pathology: implications for management of cancer patients in the UK. Eur J Surg Oncol 2001 September;27(6):589-94. | This paper does not relate to haematology |

| Standardised reporting of Haematology Laboratory results 3rd edition 1997. NZ J MED LAB SCI 2002;56(2):68-70. | No data (example of a reporting form for lab) |

| Recommendations for the reporting of lymphoid neoplasms: a report from the Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology. Virchows Arch 2002;441(4):314-9. | This is a discussion paper, lists recommendations but no data |

| Richards SJ, Jack AS. The development of integrated haematopathology laboratories: a new approach to the diagnosis of leukaemia and lymphoma. Clin Lab Haematol 2003 December;25(6):337-42. | This is an expert review/discussion paper |

| Jack A. Organisation of neoplastic haematopathology services: a UK perspective. Pathology (Phila) 2005 December;37(6):479-92. | This is an expert review/discussion paper |

| LaCasce A, Niland J, Kho ME, TerVeer A, Friedberg JW, Rodriguez MA et al. Potential impact of pathologic review on therapy in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL): Analysis from the national comprehensive cancer network (NCCN) NHL outcomes project. Blood 2005;106(11):789A. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Mohanty SK, Piccoli AL, Devine LJ, Patel AA, William GC, Winters SB et al. Synoptic tool for reporting of hematological and lymphoid neoplasms based on World Health Organization classification and College of American Pathologists checklist. BMC Cancer 2007;7:144. | This paper is not concerned with diagnostics |

| Perkins SL, Reddy VB, Reichard KK, Thompsen MA, Dunphy CH. Recommended curriculum for teaching hematopathology to subspecialty hematopathology fellows. Am J Clin Pathol 2007 June;127(6):962-76. | This paper is a discussion paper |

| Briggs C, Guthrie D, Hyde K, Mackie I, Parker N, Popek M et al. Guidelines for point-of-care testing: haematology. Br J Haematol 2008 September;142(6):904-15. | This paper is a list of guidelines |

| Briggs C, Carter J, LEE SH, Sandhaus L, Simon-Lopez R, Vives Corrons JL. ICSH Guideline for worldwide point-of-care testing in haematology with special reference to the complete blood count. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 2008 April;30(2):105-16. | Duplicate |

| Dworzak MN, Gaipa G, Ratei R, Veltroni M, Schumich A, Maglia O et al. Standardization of flow cytometric minimal residual disease evaluation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Multicentric assessment is feasible. Cytometry Part B, Clinical Cytometry 2008 November;74(6):331-40. | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| Hamdani SNR. Second opinion in pathology of lymphoid lesions - An audit. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 2008;24(6):798-802. | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| NE, Owen RG, Bedu-Addo. UK-based real-time lymphoproliferative disorder diagnostic service to improve the management of patients in Ghana. Journal of Hematopathology 2009;2(3):143-9. | This study was about improving diagnosis and management in Ghana |

| Chun K, Hagemeijer A, Iqbal A, Slovak ML. Implementation of standardized international karyotype scoring practices is needed to provide uniform and systematic evaluation for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome using IPSS criteria: An International Working Group on MDS Cytogenetics Study. Leuk Res 2010;34(2):160-5. | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| Fang CHO. When are diagnostic laboratory tests cost-effective? A systematic review of cost-utility analyses. Value in Health 2010;Conference(var.pagings):A101. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Hall J, Foucar K. Diagnosing myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms: laboratory testing strategies to exclude other disorders. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 2010;32(6):559-71. | This is a discussion paper/expert review |

| Siftar Z, Siftar Z, Paro MMK, Sokolic I, Nazor A, Mestric ZF. External quality assessment in clinical cell analysis by flow cytometry. Why is it so important? Coll Antropol 2010 March;34(1):207-17. | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| Stevens WBC. Impact of centralised multidisciplinary expert re-evaluation of diagnostic procedures in patients with newly diagnosed hodgkin lymphoma. Haematologica 2010 October 1;Conference(var.pagings):01. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Ireland R. Haematological malignancies: the rationale for integrated haematopathology services, key elements of organization and wider contribution to patient care. Histopathology 2011 January;58(1):145-54. | Review article with no data |

| Jaffe ES. Centralized review offers promise for the clinician, the pathologist, and the patient with newly diagnosed lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2011 April 10;29(11):1398-9. | This is a discussion paper/expert review |

| Ogwang MD, Ogwang MD. Accuracy of Burkitt lymphoma diagnosis in constrained pathology settings: importance to epidemiology. ARCH PATHOL LAB MED 2011 April;135(4):445-50. | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| Rogers R. Can we speed up lymphoma fast tracks? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011 June;Conference(var.pagings):June. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Roman E. Evaluation of the completeness of national haematological malignancy registration: Comparison of national data with a specialist population-based register. Br J Haematol 2011 April;Conference(var.pagings):April. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Toptas TS. Microscopic examination of bone marrow aspiration smears: Diagnostic agreement of hematologists and hematopathologists on common hematological diagnoses. Haematologica 2011 June 1;Conference(var.pagings):01. | This is a conference abstract only |

| British Committee for Standards in Haematology and Royal College of Pathologists. Best Practice in Lymphoma Diagnosis and Reporting - Specific Disease Appendix. 2012. | This is a discussion paper/expert review, Consensus based recommendations not evidence based |

| Doshi R. Re-audit of central review cases to identify trends in light of the nice iog on haematological cancers. J Pathol 2012 March;Conference(var.pagings):March. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Engel-Nitz NME. Changes in diagnoses and outcomes for patients of hematopathology specialty and other laboratories. Blood 2012;Conference(var.pagings). | This is a conference abstract only |

| Finkelstein A. Addenda in pathology reports: Trends and their implications. Am J Clin Pathol 2012;137(4):606-11. | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not include integrated reporting |

| Kohlmann A, Martinelli G, Hofmann WK, Kronnie G, Chiaretti S, Preudhomme C et al. The Interlaboratory Robustness of Next-Generation Sequencing (IRON) Study Phase II: Deep-Sequencing Analyses of Hematological Malignancies Performed by an International Network Involving 26 Laboratories. Blood 2012;120(21). | This is a conference abstract only |

| Merino A. External quality assessment scheme (EQAS) for blood smear interpreation: Evaluation of the results after one year experience. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 2012 June;Conference(var.pagings):June. | This is a conference abstract only |

| National Cancer Action Team and the Royal College of Pathologists. Additional Best Practice Commissioning Guidance for Developing Haematology Diagnostic Services. 2012. | This paper discusses integrated reporting and methods of achieving this but it is a discussion paper. |

| Orem J, Sandin S, Weibull CE, Odida M, Wabinga H, Mbidde E et al. Agreement between diagnoses of childhood lymphoma assigned in Uganda and by an international reference laboratory. Clinical Epidemiology 2012;4:339-47. | This study examined agreement in diagnosis between a Ugandan lab and a reference lab in the Netherlands |

| Van Der Walt J. Audit of lymphoma reporting in a regional referral centre. J Pathol 2012 September;Conference(var.pagings):September. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Westers TM, Westers TM. Standardization of flow cytometry in myelodysplastic syndromes: a report from an international consortium and the European LeukemiaNet Working Group. Leukemia 2012 July;26(7):1730-41. | This is a discussion paper/expert review |

| Agarwal R, Juneja S. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of haematological malignancies. NZ J MED LAB SCI 2013;67(2):39-44. | This is a discussion paper/expert review |

| Anliker M, Hammerer-Lercher A, Falkner A, Heiss B, Willenbacher W, Schrezenmeier H et al. Laboratory examination of hematologic diseases in the Interdiscipline Hematologic Competence Center (IHK) of Innsbruck of the Clinic for Hemato-Oncology V of the University Hospital Innsbruck and the Central Laboratory of the University Hospital Innsbruck. Laboratoriumsmedizin-Journal of Laboratory Medicine 2013;37(1):53-63. | Foreign Language |

| Chan C. Lessons we learn from hematopathology consultation in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2013;112(12):738-48. | This is a discussion paper/expert review |

| Cox H, Cox H. Translating biomedical science into clinical practice: Molecular diagnostics and the determination of malignancy. Health: an Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness & Medicine 2013 July;17(4):391-406. | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| Deetz CO, Scott MG, Ladenson JH. Use of a United States-based laboratory as a hematopathology reference center for a developing country: logistics and results. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 2013 February;35(1):77-81. | This paper was not about integrated reporting but about whether using overseas labs can act as reference labs in developing countries |

| Fanelli A. One year experience of a qualitative scoring scheme for EQA blood smear interpretation. Biochimica Clinica 2013;Conference(var.pagings):2013. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Forlenza CJ, Forlenza CJ. Pathology turnaround time in pediatric oncology: a tool to prepare patients and families for the diagnostic waiting period. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013 October;35(7):534-6. | This paper does not relate to haematology |

| Kohlmann A, Martinelli G, Alikian M, Artusi V, Auber B, Belickova M et al. The Interlaboratory Robustness Of Next-Generation Sequencing (IRON) Study Phase II: Deep-Sequencing Analyses Of Hematological Malignancies Performed In 8,867 Cases By An International Network Involving 27 Laboratories. Blood 2013;122(21). | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| N A. External quality assessment scheme (EQAS) for blood smear interpretation: Evaluati on of the results after two years experience. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 2013 May;Conference(var.pagings):May. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Rondoni M. Hematologic diagnostic centralized laboratory of a big area enables to acquire actual epidemiologic data of incidence of AML and improves accuracy of diagnosis: Analysis of two years of activity focused on acute myeloid leukemias. Haematologica 2013 October 1;Conference(var.pagings):01. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Azzato EM, Morrissette JJD, Halbiger RD, Bagg A, Daber RD. Development and implementation of a custom integrated database with dashboards to assist with hematopathology specimen triage and traffic. J Pathol Inform 2014 August 28;5:29. | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| Brenneman SK, Belland AV, Hulbert EM, Korrer S. Hematologic Malignancies: Impact of an Integrated Pathology Process and Decision Support Tool on Diagnosis and Follow-up Health Care Costs. Blood 2014;124(21). | This is a conference abstract only |

| Brodska H. Possible pitfalls in laboratory examination of patient with a hematological disease. Klinicka Biochemie a Metabolismus 2014;22(1):11-5. | Foreign Language – no translation |

| Cheung CC, Torlakovic EE, Chow H, Snover DC, Asa SL. Modeling complexity in pathologist workload measurement: the Automatable Activity-Based Approach to Complexity Unit Scoring (AABACUS). Mod Pathol 2014;article in press. | Not relevant to the question of integrated diagnostics |

| Ciabatti E. Myelodysplastic syndromes: A multidisciplinary integrated diagnostic work-up for patients' risk stratification. Blood 2014;Conference(var.pagings). | This is a conference abstract only |

| Ciabatti E. Myelodysplastic syndromes: How ameliorate the accuracy of diagnosis by applying an integrated molecular/cytogenetic workup. Haematologica 2014 October 1;Conference(var.pagings):01. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Gerrie AS, Huang SJ. Population-based characterization of the genetic landscape of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients referred for cytogenetic testing in British Columbia, Canada: the role of provincial laboratory standardization. Cancer Genetics 2014 July;207(7-8):316-25. | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| Johansson U, Johansson U, Bloxham D, Couzens S, Jesson J, Morilla R et al. Guidelines on the use of multicolour flow cytometry in the diagnosis of haematological neoplasms. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol 2014 May;165(4):455-88. | This paper is a list of recommendations relating the use of flow cytometry |

| Johnston A. Challenges faced by laboratories in differentiating between reactive (nonneoplastic) lymphocytes and neoplastic lymphocytes in a blood smear. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 2014 June;Conference(var.pagings):June. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Merino A. External quality assessment scheme (EQAS) for blood smear interpretation: Evaluation of the results after three years experience. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 2014 June;Conference(var.pagings):June. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Patel KPR. Development of a quality assurance framework for clinical reporting of next-generation sequencing-based molecular oncology testing. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 2014;Conference(var.pagings):778. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Raya JM, Montes-Moreno S. Pathology reporting of bone marrow biopsy in myelofibrosis; application of the Delphi consensus process to the development of a standardised diagnostic report. J Clin Pathol 2014 July;67(7):620-5. | Outcomes were not relevant to the topic. This study was about identifying the essential components of a standardised report. |

| Haghi N. Utility and cost effectiveness of cytogenetic analysis in cases of suspected lymphoma. Lab Invest 2015 February;Conference(var.pagings):February. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Montgomery N. Collaborative telepathology bolsters diagnostic and research capabilities in a resource limited setting. Lab Invest 2015 February;Conference(var.pagings):February. | This is a conference abstract only |

| Bjorklund E, Matinlauri, Bjorklund E, Matinlauri I, Tierens A, Axelsson S et al. Quality control of flow cytometry data analysis for evaluation of minimal residual disease in bone marrow from acute leukemia patients during treatment. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2009 June;31(6):406 | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| Cooper MN, de Klerk NH, Greenop KR, Jamieson SE, Anderson, Cooper MN. Statistical adjustment of genotyping error in a case | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

| Siddiqui K, Siddiqui K. Development and implementation of a distributed integrated data | This paper is not relevant to the current topic – does not discuss integrated reporting |

The staffing and facilities (levels of care) needed to treat haematological cancers and support adults and young people who are having intensive, non-transplant chemotherapy

Review Question

How should level of care be defined and categorised for people with haematological cancers who are having intensive (non-transplant) chemotherapy considering:

- Diagnosis

- Comorbidities and frailty

- Medicine Regimens

- Management of medicine administration and toxicities

Does the level of care affect patient outcome for people with haematological cancers who are having intensive, non-transplant chemotherapy, considering;

- Location

- Staffing levels

- Centre size/specialism

- Level of in-patient isolation

- Ambulatory care

- Prophylactic anti-infective medications

Background

Most patients who require curative treatment for aggressive haematological malignancies such as acute leukaemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome, receive several cycles of intensive chemotherapy and the protocols used to treat these patients typically lower the blood cell count leading to severe neutropenia resulting in a neutrophil count of less than 0.5 ×109/L. Other toxicities may also be a feature, and older patients and those with co-morbidities are at a higher risk of complications.

Despite improvements in supportive care, these patients are at a high risk of serious and potentially life-threatening infections and other complications.

In recent multicentre UK studies, early mortality following AML induction chemotherapy has been reported as up to 6% and 9% at 30 days and 10% and 15% at 60 days in younger and older patients respectively (Burnett et al Blood 2015; 125, 3878-3885, Burnett et al JCO 2012; 30,3924-31).

Reported induction mortality is also substantial in ALL; 4% in patients <55 and 18% in patients over 55 years (Sive et al BJH 2012;157:463-71). Early mortality in ALL is not improved with the introduction of modern drugs, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Philadelphia positive disease (Fielding AK et al Blood 2014;123, 843-50). Recent data confirm a 2.2% induction death rate in 16-25 year olds treated on paediatric protocols. In 25 – 60 year olds treated on the current NCRI UKALL 14 type schedule, the induction death rate in UKALL 14 currently is 8.5% (personal communication, Dr Clare Rowntree).

Given the high risks of treatments and complexity of patients and speed complications can occur, immediate availability of specialist nursing staff supported initially by medical staff and then by prompt availability) of specialist staff (i.e. consultant/registrar) cover is essential, along with prompt access to other key specialists, especially intensive care. Specialist support services, especially specialist radiology and laboratory medicine (including transfusion medicine), are also essential on both an emergency and elective basis.

Along with adequate staffing and access to specialist services, the previous 2003 IOG recommended that patients treated on these protocols were nursed for the duration of their neutropenia (14-21 days) in specialist hospital units equipped in single rooms with or without laminar flow or high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration to reduce the risk of infection. Whereas this became common practice across many NHS units, for a variety of reasons, some patients receive care on an open ward or be allowed home, either through an informal arrangement with ward staff, or, increasingly through the structured delivery of intensive treatment in carefully selected patients (e.g. younger patients with limited co-morbidities) in the ambulatory care setting. However, promptness of clinical review by specialist staff also has to be in place for ambulatory care, where forward planning and policies are of major importance as the patient will have the additional ‘lag-phase’ of having to self-refer from home or hospital flat before assessment. This has to be balanced against NHS deliverability within working directives and generic/non-specialist hospital at night initiatives etc.

Despite being stipulated by the previous IOG and peer review recommendations, the provision of isolation rooms to protect intensively treated patients against nosocomial infections has proved challenging for NHS units despite rising levels of C. difficile, VRE, MRSA and other antibiotic resistant strains, along with seasonal respiratory viral infections (like influenza) in this population of patients, who are also susceptible to airborne fungal infections.. Although the benefits of isolation are well established in some contexts, it is not clear whether particular levels of protection are more effective in preventing fungal, bacterial and viral infections in severely immunocompromised patients than others. (e.g. standard en-suite rooms compared to more complex laminar flow and HEPA filtration). In any unit, isolation facilities, whether they are simple or complex, are a limited resource. Mandatory NHS isolation policies, designed to protect hospital inpatients as a whole, may impact significantly on bed availability for the intensively treated acute leukaemia patients, particularly during infectious epidemics such as influenza or outbreaks of antibiotic resistant infection. If isolation rooms for this patient population are not available at short notice, chemotherapy treatments may be delayed, or patients looked after in open wards or at home with informal arrangements, all of which may affect survival outcomes.

The standards of care required to deliver chemotherapy to patients with haematological cancer were previously classified according to the complexity of chemotherapy and duration of neutropenia. The 2003 haemato-oncology IOG and subsequent peer review standards stipulated a minimum of five intensive level 2 patients had to be treated per year but the recommendations were imprecise and open to interpretation, with both new and relapsed patients and a number of less intense lymphoma salvage regimens (such as DHAP and ESHAP etc) being potentially included. A further system of classification came from the updated BCSH recommendations. Three levels of care were defined predominantly relating to the facilities and support services required for patient care (BCSH Haematology Task Force, 2009). Whilst there was recognition that some patients may be managed from home, there was no major consideration of delivery of chemotherapy in the ambulatory care setting. Factors such as minimum numbers of patients required per ‘level’ of care, staff training and competency assessments were not specifically addressed in the BCSH guidelines for the facilities required for the treatment of adults with haematological malignancy (BCSH Haematology Task Force, 2009),

For haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), the international FACT-JACIE accreditation standards for transplant programme stipulate minimum numbers for clinical activity. Despite early deaths from intensive induction chemotherapy for acute leukaemia being consistently higher than those associated with autologous stem cell transplantation (where UK adult 100 and 365 day non-relapse mortality is 2%) and closer to that for allogeneic transplantation (7% at 100 days rising to 16% at 1 year), there is no well defined minimum recommended threshold for unit activity in intensive chemotherapy (reference BSBMT 6th Report to Specialist Commissioners (2015), http://BSBMT.org). Although minimum transplant activity thresholds are not evidence based, there is evidence that implementation of FACT-JACIE standards in haematological practice results in survival benefits for high-risk treatments (Gratwohl A et al Haematologica 2014; 99; 908-15).. There is also a case for having enough patients to perform meaningful analysis of survival outcomes and other audits within any unit undertaking intensive and complex treatments in this high-risk but potentially curable population of cancer patients.

In this IOG update there is a need to review and make clear evidence based recommendations for 24 hour specialist staffing levels and accessibility to isolation facilities, ITU and other support specialities. These are complex facilities and minimum numbers of patients with acute leukaemia and related conditions patients being treated with intensive chemotherapy in an individual unit need consideration in this IOG update. The update takes into account the potential clinical, patient experience and economic impact of intensive chemotherapy treatment in conventional or ambulatory care settings. Age and co-morbidities will also be a necessary consideration.

Levels of Care

A range of different levels of care, corresponding with the variety of diseases treated by haematology services, is required to manage patients with haematological cancers. Patients with acute leukaemia need repeated periods of intensive in-patient treatment lasting between four and seven months (depending on their diagnosis); 85-95% will be re-admitted as emergencies with febrile neutropenia on repeated occasions during this time (Flowers et al). By contrast, patients with conditions at the opposite end of the spectrum of aggressiveness, such as stage A chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, may need little more than regular monitoring.

The level of care required is based primarily on the duration and depth of neutropenia associated with different chemotherapy regimens. Patients being treated with regimens or dose schedules with a risk of brief and / or mild neutropenia can be managed on an outpatient basis. Patients being treated with regimens that usually cause prolonged, severe neutropenia, with a high risk of febrile neutropenia, require additional support and facilities. While some patients requiring these regimens may be treated in an outpatient setting, pathways need to be put in place to allow rapid access to inpatient care as required.

The British Committee for Standardisation in Haematology (BCSH) guidelines currently define four levels of care (level 1, 2a, 2b and 3). Level 2b is currently defined as treatment regimens which encompasses those that will predictably cause prolonged periods of neutropenia, would normally be given on an inpatient basis, and which may need to be given at weekends as well as during the week. According to BCSH guidelines, these regimens are more complex to administer than at the current level 1 or 2a and have a greater likelihood of resulting in medical complications in addition to predictable prolonged neutropenia. Consequently, the resources required to deliver these more complex regimens are greater than those needed for level 1 or 2a regimens. Level 3 care refers to complex regimens such as therapy for acute lymphoblastic lymphoma.

Historically, patients receiving treatment for Burkitt lymphoma or salvage chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma were considered to be at risk of severe neutropenia. As a result these patients were treated according to the guidelines for level 2b patients. Data for the commonly used salvage regimens (e.g. DHAP, ESHAP and GDP with or without Rituximab) however show that these patients have a much lower risk of prolonged, severe neutropenia than previously thought. Consequently these patients may not require the same complex level of care, resource or facilities use as patients requiring induction therapy for conditions such as acute myeloid leukaemia or Burkitt lymphoma.

The guideline committee considered both the original levels of care defined in the NICE Haematology IOG (2003) and the two versions of the BCSH Guidelines (1995 and 2009) in conjunction with published data relating to toxicity of different regimens with the aim of redefining level 2b and 3 care from the BCSH guidelines and level 2 care from the IOG 2003, using a new definition based solely on the depth and duration of severe neutropenia expected for each regimen and patient group. The levels of care have therefore been redefined as non-intensive chemotherapy, intensive chemotherapy and haematopoietic Stem cell transplantation (HSCT, covering both autologous and allogeneic HSCT procedures).:

This guideline is concerned with patients receiving intensive chemotherapy regimens. The definition of intensive chemotherapy is any regimen which is anticipated to result in severe neutropenia of less than 0.5 ×109/L for greater than 7 days, which largely limits the chemotherapy regimens to those used for AML (including acute promyelocytic leukaemia), high-risk MDS, ALL and Burkitt and lymphoblastic lymphomas (table 1).

Table 1

Levels of Care.

The use of other regimens that produce this degree of neutropenia is rare, but exceptional intensive treatment of other haematological malignancies is not excluded from this definition (table 2).

Table 2

Chemotherapy regimens and associated toxicities.

Question in PICO format

| Population | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults and young people (16 years and older) with haematological malignancies and receiving intensive, non-transplant chemotherapy resulting in >7 days of neutropenia of >0.5 ×109/L |

| Each Other |

|

Searching and Screening

| Database name | Dates Covered | No of references found | No of references retrieved | Finish date of search |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medline | 1996-Jul 2015 | 4001 | 164 | 15/07/2015 |

| Premedline | Jul 13 2015 | 462 | 13 | 14/07/2015 |

| Embase | 1996-Apr 2015 | 2480 | 209 | 15/07/2015 |

| Cochrane Library | Issue , Jul 2015 | 113 | 3 | 20/07/2015 |

| Web of Science (SCI & SSCI) and ISI Proceedings | 1900-2015 | 3742 | 188 | 20/07/2015 |

| HMIC | All | 7 | 3 | 14/07/2015 |

| PscyInfo | 1806-Jul 2015 | 25 | 3 | 14/07/2015 |

| CINAHL | 1995 | 31 | 21/07/2015 | |

| Joanna Briggs Institute EBP database | Current to Jul 08 2015 | 78 | 3 | 14/07/2015 |

| OpenGrey | 5 | 0 | 22/07/2015 | |

| HMRN (Haematological Malignancy Research Network) | 3 | 0 | 22/07/2015 | |

| British Committee for Standards in Haematology | 35 | 3 | 22/07/2015 |

Total References retrieved (after databases combined, de-duplicated and sifted): 558

Medline search strategy (This search strategy is adapted to each database.)

- exp Hematologic Neoplasms/

- ((haematolog* or hematolog* or blood or red cell* or white cell* or lymph* or marrow or platelet*) adj1 (cancer* or neoplas* or oncolog* or malignan* or tumo?r* or carcinoma* or adenocarcinoma* or sarcoma*)).tw.

- exp Lymphoma/

- lymphoma*.tw.

- (lymph* adj1 (cancer* or neopla* or oncolog* or malignan* or tumo?r*)).tw.

- hodgkin*.tw.

- lymphogranulomato*.tw.

- exp Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin/

- (nonhodgkin* or non-hodgkin*).tw.

- lymphosarcom*.tw.

- reticulosarcom*.tw.

- Burkitt Lymphoma/

- (burkitt* adj (lymphom* or tumo?r* or cancer* or neoplas* or malign*)).tw.

- brill-symmer*.tw.

- Sezary Syndrome/

- sezary.tw.

- exp Leukemia/

- (leuk?em* or AML or CLL or CML).tw.

- exp Neoplasms, Plasma Cell/

- myelom*.tw.

- (myelo* adj (cancer* or neopla* or oncolog* or malignan* or tumo?r*)).tw.

- kahler*.tw.

- Plasmacytoma/

- (plasm?cytom* or plasm?zytom*).tw.

- (plasma cell* adj3 (cancer* or neoplas* or oncolog* or malignan* or tumo?r* or carcinoma* or adenocarcinoma*)).tw.

- Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia/

- waldenstrom.tw.

- exp Bone Marrow Diseases/

- exp Anemia, Aplastic/

- (aplast* adj an?em*).tw.

- exp Myelodysplastic-Myeloproliferative Diseases/

- exp Myeloproliferative Disorders/

- exp Myelodysplastic Syndromes/

- exp Thrombocytopenia/

- (thrombocytop?eni* or thrombocyth?emi* or poly-cyth?emi* or polycyth?emi* or myelofibros or myelodysplas* or myeloproliferat* or dysmyelopoietic or haematopoetic or hematopoetic).tw.

- exp Anemia, Refractory/

- (refractory adj an?em*).tw.

- (refractory adj cytop?en*).tw.

- Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance/

- (monoclonal adj gammopath*).tw.

- (monoclonal adj immunoglobulin?emia).tw.

- MGUS.tw.

- ((oncohaematolog* or oncohematolog*) adj2 (disorder* or disease* or syndrome*)).tw.

- or/1-42

- limit 44 to yr=“2000 - 2015”

- exp Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols/st

- exp Antineoplastic Agents/st

- Antimetabolites, Antineoplastic/st

- (chemotherap* adj (regim* or protocol* or combin*)).tw.

- intensive chemotherap*.tw.

- (immunochemotherap* or immuno-chemotherap*).tw.

- polychemotherap*.tw.

- or/46-52

- FLAG.tw.

- Fludarabine/

- Cytarabine/

- Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor/

- 55 and 56 and 57

- ((fludarabine or fludara) and (cytarabine or “Ara C” or “cytosine arabinoside”) and (g-csf or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor)).tw.

- 54 or 58 or 59

- FLAG-IDA.tw.

- Idarubicin/

- 58 and 62

- (idarubicin or zavedos).tw.

- 59 and 64

- 61 or 63 or 65

- DHAP.tw.

- exp Dexamethasone/

- Cisplatin/

- 68 and 69 and 56

- ((dexamethasone or decadron or oradexon or dexafree or dexsol) and (cytarabine or “Ara C” or “cytosine arabinoside”) and (cisplatin or platinol)).tw.

- 67 or 70 or 71

- ESHAP.tw.

- Etoposide/

- exp Methylprednisolone/

- 74 and 75 and 56 and 69

- ((etoposide or VP-16 or etopophos or vepesid) and (cytarabine or “Ara C” or “cytosine arabinoside”) and (cisplatin or platinol) and methylprednisolone).tw.

- 73 or 76 or 77

- IVE.tw.

- Ifosfamide/

- Epirubicin/

- 80 and 81 and 74

- ((ifosfamide or mitoxana) and (epirubicin or pharmorubicin) and (cytarabine or “Ara C” or “cytosine arabinoside”) and (etoposide or VP-16 or etopophos or vepesid)).tw.

- 79 or 82 or 83

- ICE.tw.

- Carboplatin/

- 80 and 86 and 74

- ((ifosfamide or mitoxana) and carboplatin and (etoposide or VP-16 or etopophos or vepesid)).tw.

- 85 or 87 or 88

- (mini-BEAM or BEAM).tw.

- Carmustine/

- Melphalan/

- 91 and 74 and 56 and 92

- ((carmustine or BICNU) and (etoposide or VP-16 or etopophos or vepesid) and (cytarabine or “Ara C” or “cytosine arabinoside”) and melphalan).tw.

- 90 or 93 or 94

- DT-PACE.tw.

- Thalidomide/

- Doxorubicin/

- Cyclosphamide/

- 68 and 97 and 69 and 98 and 99 and 74

- ((dexamethasone or decadron or oradexon or dexafree or dexsol) and (thalidomide or celgene) and (cisplatin or platinol) and (doxorubicin or adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide and (etoposide or VP-16 or etopophos or vepesid)).tw.

- 96 or 100 or 101

- CODOX-M IVAC.tw.

- Vincristine/

- Methotrexate/

- 99 and 104 and 98 and 105 and 74 and 80 and 56

- (cyclophosphamide and (vincristine or oncovin) and (doxorubicin or adriamycin) and methotrexate and (etoposide or VP-16 or etopophos or vepesid) and (ifosfamide or mitoxana) and (cytarabine or “Ara C” or “cytosine arabinoside”)).tw.

- 103 or 106 or 107

- DA.tw.

- Daunorubicin/

- 56 and 110

- (daunorubicin and (cytarabine or “Ara C” or “cytosine arabinoside”)).tw.

- 109 or 111 or 112

- ADE.tw.

- 56 and 110 and 74

- ((cytarabine or “Ara C” or “cytosine arabinoside”) and daunorubicin and (etoposide or VP-16 or etopophos or vepesid)).tw.

- 114 or 115 or 116

- (FLAG or FLAG-IDA or DHAP or ESHAP or IVE or ICE or BEAM or mini-BEAM or DT-PACE or CODOX-M IVAC or DA or ADE).ps.

- 53 or 60 or 66 or 72 or 78 or 84 or 89 or 95 or 102 or 108 or 113 or 117

- rituximab.tw.

- 119 and 120

- 119 or 121

- exp Precursor Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia-Lymphoma/

- leuk?emi*.tw.

- (akut$ or acut$).tw.

- 124 and 125

- 123 or 126

- Induction Chemotherapy/

- Consolidation Chemotherapy/

- (chemotherap* adj2 (induction or consolidat* or intensi*)).tw.

- or/128-130

- 127 and 131

- 122 or 132

- 45 and 133

- exp Health Services/ma, st, ut

- models, organizational/

- exp Health Resources/og, st, ut

- exp “Delivery of Health Care”/ma, mt, og, st, ut

- Health Services Accessibility/og, st

- Patient-Centered Care/ma, mt, og, st, ut

- patient care plan*.tw.

- Health Facilities/ma, st, ut

- exp Health Facility Size/ma, og, st, sd

- Health Manpower/

- Specialization/

- “Delivery of Health Care, Integrated”/

- (“model* of care” or “level* of care” or “care model*” or “standard* of care” or “care standard*”).tw.

- (“care coordination” or “care co-ordination”).tw.

- (specialist* or expert* or expertise).tw.

- Centralized Hospital Services/

- ((integrat* adj3 healthcare) or (integrat* adj3 health care) or (integrat* adj3 service*) or (integrat* adj3 care*)).tw.

- ((integrat$ adj3 provision) or (integrat$ adj3 organisation$)).tw.

- (supercentre* or supercenter* or “super centre*” or “super center*”).tw.

- exp Regional Health Planning/

- ((local adj hospital*) or facility* or centre* or center* or service* or clinic* or unit* or site*).tw.

- ((outreach or satellite*) adj (healthcare or health care or care or service* or centre* or center* or clinic* or unit* or department* or facilit* or site*)).tw.

- co-locat*.tw.

- Cancer Care Facilities/

- Oncology Service, Hospital/

- Medical Oncology/ma, og, st

- Ancillary Services, Hospital/

- (support* adj (service* or facilit* or unit* or department* or on-site)).tw.

- ((haematolog* or hematolog* or haemato-oncolog* or hemato-oncolog* or oncolog*) adj2 (service* or facilit* or unit* or department* or on-site)).tw.

- outpatients/

- ambulatory care facilities/

- exp Ambulatory Care/ma, st, ut

- (ambulatory care or ambulatory health care or ambulatory healthcare).tw.

- (ambulatory service* or ambulatory health service*).tw.

- Outpatient Clinics, Hospital/

- (outpatient* or out-patient*).tw.

- Day Care/ma, og, st, ut

- (day adj (care or case* or unit* or facilit*)).tw.

- Hospital Shared Services/

- shared care.tw.

- exp Hospitalization/

- ((hospital* or inpatient* or in-patient* or patient*) adj (admission* or admitted or readmission* or re-admission* or readmitted or re-admitted)).tw.

- Patient Isolation/

- (patient* adj2 isolat*).tw.

- Hemodialysis Units, Hospital/

- exp Emergency Medical Services/ma, og, st, ut

- (emergenc* adj (healthcare or health care or care or service* or centre* or center* or clinic* or unit* or department* or facilit* or site*)).tw.

- Intensive Care Units/

- exp Critical Care/ma, og, st, ut

- (critical care or intensive care or high dependency or ICU or HDU).tw.

- (intensive therapy unit or ITU).tw.

- exp health personnel/

- staff*.tw.

- (haematologist* or hematologist* or haemato-oncologist* or hemato-oncologist* or oncologist*).tw.

- Nursing Services/

- Oncology Nursing/

- (nurs* adj2 (haematolog* or hematolog* or haemato-oncolog* or hemato-oncolog*)).tw.

- Nurse's Role/

- Clinical Nursing Research/

- Inservice Training/og, st

- Pharmacies/ma, og, st, ut

- exp Pharmaceutical Services/

- Pharmacists/

- exp Home Care Services/

- (home adj2 (care or nursing or service*)).tw.

- exp Community Health Services/

- (communit* adj2 (care or nursing or service* or clinic*1 or unit* or centre* or center*)).tw.

- Social Support/

- Palliative Care/ma, og, st, ut

- Catheterization, Central Venous/st, ut

- (prophyla* adj2 (anti-fungal* or antiviral* or antibiotic*)).tw.

- Catheter-Related Infections/pc

- Bacterial Infections/pc

- Bacteremia/pc

- Cross Infection/pc

- exp Infection Control/mt, og, st

- Environment, Controlled/

- *Filtration/

- HEPA filtration.tw.

- high efficiency particulate air filtration.tw.

- (air adj2 (filtration or filter*)).tw.

- or/135-215

- 134 and 216

Study Quality

The evidence for this topic comprises one systematic review and meta-analysis; one randomised trial; one randomised cross-over study; one prospective study; one audit and four retrospective comparative studies.

A number of factors were identified which impacted the quality of the evidence including study populations which were not exclusively low risk haematology patients, retrospective, non-randomised methodology, selection bias, small sample sizes and possible recall bias.

| Study | Study Type/Setting | Aim | Population | Intervention | Comaprison | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bakshi et al (2009) | Retrospective Analysis | To assess the outcomes of high dose cytosine arabinoside consolidation cycles versus inpatient in paediatric AML patients | N=30 | Outpatient Chemotherapy | Inpatient Chemotherapy |

|

| 2 | Hutter et al (2009) | Retrospective cohort control | To assess thecorrelation between improvement of room comfort conditions in patients with newly diagnosed AML on a haematological waard and the incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis | N=63 | Post Room Renovation

| Pre Room Renovation

|

|

| 3 | Lehrnbecher et al (2012) | Retrospective Study | To assess institutional recommendations regarding restrictions of social contacts, pates and food and instructions on wearing face masks in public for children with standard risk ALL and any risk AML during intensive chemotherapy | N=336 centres in 27 countries | Recommendations on restrictions | Each other |

|

| 4 | Luthi et al (2012) | Retrospective study | N=17 | To evaluate the safety, feasibility and costs of home care for the administation of intensive chemotherapy | Chemotherapy in the home care setting | Inpatient chemotherapy |

|

| 5 | Schlesinger et al (2009) | Systematic review and meta analysis | To quantify the evidence for infection control interventions among high risk cancer patients and haematopeitic stem cell recipients | N=40 studies | Infection control interventions Protective Isolation | No intervention Placebo Other interventions |

|

| 6 | Sive et al (2012) | Audit | To present the experience in managing patients receiving intensive chemotherapy and HSCT protocols on daycare basis with full nursing and medical support while staying in a hotel within walking distance of the hospital | N=668 | Hotel Based Outpatient Care |

| |

| 7 | Sopko et al (2012) | Retrospective Case series | To investigate the safety and feasibility of home care following consolidation chemotherapy | N=45 | Home care after consolidation chemotherapy | Inpatient care after consolidation chemotherapy |

|

| 8 | Stevens et al (2005) | Randomised cross over trial | To compare two models of health care delivery for children with ALL | N=29 | Home Chemotherapy | Hospital Chemotherapy |

|

| 9 | Stevens et al (2004) | Prospective descriptive study, nested in a randomised cross over trial | To evaluate quality of life, nature and incidence of adverse effects, parental caregiver burden and direct and indirect costs of a home chemotherapy program for children with cancer | N=33 (health practitioners) | Home Chemotherapy | Hospital Chemotherapy |

|

Evidence Statements

Isolation Factors

Survival

Very low to moderate quality evidence (Grade table 1) from one systematic review and meta-analysis which included 40 studies (randomised trials and observational) (Schlesinger et al, 2009); protective isolation with any combination of methods that included air quality control reduced the risk of death at 30 days (RR=0.6; 95% CI 0.5-0.72; 15 studies, 6280 patients); 100 days (RR=0.79, 95% CI, 0.73-0.87; 24 studies, 6892 patients) and at the longest available follow-up (between 100 days and 3 years) (RR=0.86, 95% CI 0.81-0.91; 13 studies, 6073 patients).

Grade Table 1

Isolation compared to No isolation/Placebo for low risk patients.

Infection related Mortality, Risk of Infection, Antibiotic use

Very low to moderate quality evidence (Grade table 1) from one systematic review and meta-analysis which included 40 studies (randomised trials and observational) (Schlesinger et al, 2009); protective isolation reduced the occurrence of clinically and/or microbiologically documented infections (RR=0.75 (0.68-0.83) per patient; 20 studies, 1904 patients; RR=0.53 (0.45-0.63); per patient day, 14 studies, 66431 patient days).

Very low to moderate quality evidence (Grade table 1) from one systematic review and meta-analysis which included 40 studies (randomised trials and observational) (Schlesinger et al, 2009); no significant benefit of protective isolation (all studies used air quality control) was observed in relation to mould infections (RR=0.69, 0.31-1.53; 9 studies, 979 patients) nor was the need for systemic antifungal treatment reduced (RR=1.02, 95% CI 0.88-1.18; 7 studies, 987 patients).

Very low to moderate quality evidence (Grade table 1) from one systematic review and meta-analysis which included 40 studies (randomised trials and observational) (Schlesinger et al, 2009); gram positive and gram negative infections were significantly reduced, though barrier isolation was needed to show a reduction in gram negative infections (RR= 0.49 (0.40-0.62) with barrier isolation (12 trials/n=1136) versus RR=0.87 (0.61-1.24) without barrier isolation (4 trials/n=328).

Very low to moderate quality evidence (Grade table 1) from one systematic review and meta-analysis which included 40 studies (randomised trials and observational) (Schlesinger et al, 2009); the need for systemic antibiotics did not differ when assessed on a per patient basis (RR=1.01, 0.94-1.09; 5 studies, 955 patients) but the number of antibiotic days was significantly lower with protective isolation (RR=0.81, 0.78-0.85; 3 studies, 6617 patient days).

Room facilities

Very low quality evidence from one retrospective cohort-control study (Grade table 1) comparing outcomes before and after ward renovation in 63 patients (Hutter et al, 2009) reported that patients treated before renovation (2 patients per room, 6 patients sharing a toilet placed outside the room, wash basin inside the room, shower across the hospital corridor, no ventilation system, air filtration or room pressurisation, no false ceilings) stayed 3 days longer compared with those treated on the newly renovated ward (2 patients per room, separate bath room in each room equipped with toilet, wash basin and shower, no ventilation system, air filtration or room pressurisation, no false ceilings). 39% of pre-renovation patients and 34% of post-renovation patients developed an invasive pulmonary aspergillus (p=0.79) with the diagnosis usually determined on CT scan.

Ambulatory Care

Survival