Summary of evidence

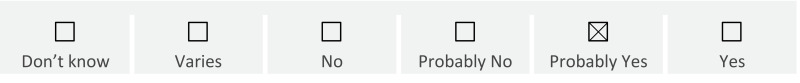

Evidence on the effects of antenatal corticosteroids versus placebo or no treatment for reducing adverse effects of prematurity was derived from an updated 2020 Cochrane review (13). A subgroup analysis was conducted in the published review, based on singleton or multiple pregnancy.

Eighteen trials contributed to the subgroup analysis. Thirteen recruited women with singleton pregnancy only. Twelve recruited women with singleton or multiple pregnancy, of which five reported some outcome data separately for women with singleton or multiple pregnancy. This subgroup analysis includes a total of 10 245 infants – 9240 in the singleton group and 1005 infants in the multiple pregnancy group.

The trials came from a range of health care systems and settings. Six studies were conducted in the United States of America, two in Brazil and one each in Colombia, India, Iran, Jordan, New Zealand, Thailand, Turkey and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. One trial took place in the USA and Germany and another study took place in Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan.

The trials recruited women with a wide range of preterm gestational ages, from 24 to <37 weeks. One trial recruited women at <29 weeks, eight trials recruited women at <34 weeks, one at <35 weeks, two at <36 weeks, five at 34 weeks and 0 days to 36 weeks and 5 days or 36 weeks and 6 days and one at <37 weeks.

Antenatal corticosteroids used in the trials included in the subgroup analysis were betamethasone (11 trials; 5392 women and 5485 infants), dexamethasone (6 trials; 4265 women and 4565 infants) and hydrocortisone (1 trial; 196 women and infants).

Antenatal corticosteroids versus placebo or no treatment: singleton and multiple births

Download PDF (294K)

Maternal outcomes

No data were available for the pre-specified maternal outcomes (severe maternal morbidity or death, maternal infectious morbidity, maternal side effects, maternal well-being, maternal satisfaction).

Infant outcomes

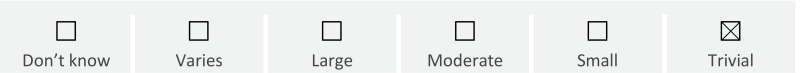

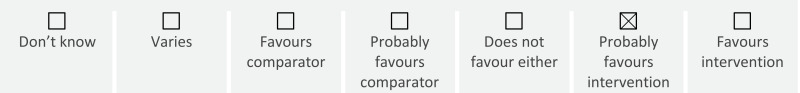

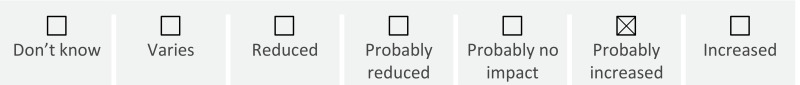

Fetal and neonatal death: In singleton pregnancies, antenatal corticosteroid therapy reduces the risk of perinatal death (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.99; 7 trials, 5492 infants; high certainty). This is largely due to a probable reduction in neonatal deaths (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.91; 13 trials, 8453 infants; moderate certainty) as they probably result in little or no difference in risk of fetal death (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.46; 7 trials, 5492 infants; moderate certainty).

In multiple pregnancies, there is probably little or no difference in risk of neonatal death (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.02; 3 trials, 813 infants; moderate certainty) and there may be little or no difference in risk of perinatal deaths (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.22; 2 trials, 252 infants; low certainty) or fetal death (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.40; 2 trials, 252 infants; low certainty).

Severe neonatal morbidity: In singleton pregnancies, antenatal corticosteroid therapy probably reduces the risk of respiratory distress syndrome (RR 0.65, 0.57 to 0.74; 17 trials, 6731 infants; moderate certainty) and intraventricular haemorrhage (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.75; 6 trials, 4494 infants; moderate certainty). In multiple pregnancies, there may be little or no difference in effect on respiratory distress syndrome (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.20; 4 trials, 323 infants; low certainty) and the evidence on intraventricular haemorrhage is very uncertain.

No data were available for moderate/severe respiratory distress syndrome, systemic infection in the first 48 hours of life, necrotising enterocolitis, chronic lung disease, patent ductus arteriosus, periventricular leukomalacia, retinopathy of prematurity, surfactant use, admission to neonatal intensive care, infection in neonatal intensive care, mean duration of hospitalization, use of mechanical duration, mean duration of mechanical duration or neonatal hypoglycaemia.

Birth weight: No data were available for mean birth weight, low birth weight, small for gestational age.

Long-term morbidity: No data were available for infant or childhood death, cerebral palsy, developmental delay, intellectual impairment, hearing impairment, visual impairment, behavioural/learning difficulties in childhood.

Additional considerations

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses involve splitting available trials into different groups of participants. However, it should be acknowledged that subgroup analyses are not based on randomized comparisons, and are therefore susceptible to possible biases affecting observational studies (14). In this subgroup analysis, statistical tests for heterogeneity suggest that there are no differences in effect between singleton and multiples, for the available outcomes.

Observational evidence

A 2021 meta-analysis of observational studies investigated the effect of antenatal corticosteroids in women with multiple pregnancies (15). While available evidence was very low quality, the authors reported a reduced risk of neonatal death (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.81; 11 studies), respiratory distress syndrome (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.82; 14 studies), intraventricular haemorrhage (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.83; 11 studies) and periventricular leukomalacia (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.92; 8 studies). There was little or no difference in risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.36; 7 studies), retinopathy of prematurity (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.11; 7 studies) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.23; 8 studies). There was high heterogeneity in results for respiratory distress syndrome (p<0.001, I2=91.4%), mortality (p<0.001, I2=85.9%), intraventricular haemorrhage (p<0.001, I2=77.4%) and periventricular leukomalacia (p<0.001, I2=75.5%).