This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians who care for cancer patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

General Information About Childhood Hodgkin Lymphoma

Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer.[1] Between 1975 and 2010, childhood cancer mortality decreased by more than 50%. For Hodgkin lymphoma, the 5-year survival rate has increased over the same time from 81% to more than 95% for children and adolescents.[1]

Overview of Childhood Hodgkin Lymphoma

Childhood Hodgkin lymphoma is one of the few pediatric malignancies that shares aspects of its biology and natural history with an adult cancer. When treatment approaches for children were modeled after those used for adults, substantial morbidities resulted from the unacceptably high radiation doses. Thus, new strategies utilizing chemotherapy and lower-dose radiation were developed.

Approximately 90% to 95% of children with Hodgkin lymphoma can be cured, prompting increased attention to devising therapy that lessens long-term morbidity for these patients. Contemporary treatment programs use a risk-based and response-adapted approach in which patients receive multiagent chemotherapy with or without low-dose involved-field or involved-site radiation therapy. Prognostic factors used in determining chemotherapy intensity include stage, presence or absence of B symptoms (fever, weight loss, and night sweats), bulky disease, extranodal involvement, and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Epidemiology

Hodgkin lymphoma comprises 6% of childhood cancers. In the United States, the incidence of Hodgkin lymphoma is age related and is highest among adolescents aged 15 to 19 years (29 cases per 1 million per year); children aged 10 to 14 years, 5 to 9 years, and 0 to 4 years have approximately threefold, eightfold, and 30-fold lower rates, respectively, than do adolescents.[2] In developing countries, there is a similar incidence rate in young adults but a much higher incidence rate in childhood.[3]

Hodgkin lymphoma has the following unique epidemiological features:

- Bimodal age distribution. Hodgkin lymphoma has a bimodal age distribution that differs geographically and ethnically in industrialized countries; the early peak occurs in the middle-to-late 20s and the second peak after age 50 years. In developing countries, the early peak occurs before adolescence.[4]

- Age cohorts. Hodgkin lymphoma can be segregated into the following three age cohorts because of the variation in etiologies and histological subtypes (refer to Table 1):

- -

Children: Individuals aged 14 years and younger have a higher prevalence of nodular lymphocyte-predominant disease and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–associated mixed-cellularity disease.

Early exposure to common infections in early childhood appears to decrease the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma, most likely by maturation of cellular immunity.[7,8]

There are more males than females affected in the younger age cohort, especially in children younger than 10 years. EBV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma increases in prevalence in association with larger family size and lower socioeconomic status.[4]

- -

Adolescent and young adult: Hodgkin lymphoma in individuals aged 15 to 34 years is associated with a higher socioeconomic status in industrialized countries, increased sibship size, and earlier birth order.[9] The lower risk of Hodgkin lymphoma observed in young adults with multiple older, but not younger, siblings, is consistent with the hypothesis that early exposure to viral infection (which the siblings bring home from school, for example) may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.[7]

Nodular-sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common subtype, followed by mixed cellularity.

- -

Older adult: Hodgkin lymphoma most commonly presents in individuals aged 55 to 74 years. This group has a higher risk of lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma. The treatment of older adults is not discussed in this summary.

- Family history. A family history of Hodgkin lymphoma in siblings or parents has been associated with an increased risk of this disease.[10,11] In a population-based study that evaluated risk of familial classical Hodgkin lymphoma by relationship, histology, age, and sex, the cumulative risk of Hodgkin lymphoma was 0.6%, representing a 3.3-fold increased risk compared with the general population risk.[12] The risk in siblings was significantly higher than the risk in parents and/or offspring. The risk in sisters was higher than the risk in brothers or siblings of opposite sex. The lifetime risk of Hodgkin lymphoma was higher when first-degree relatives were diagnosed before age 30 years.

Table

Table 1. Epidemiology of Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) Across the Age Spectruma.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Hodgkin lymphoma

EBV has been implicated in the causation of some cases of Hodgkin lymphoma. Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma may have high EBV titers, suggesting that a previous infection with EBV may precede the development of Hodgkin lymphoma in some patients. EBV genetic material can be detected in Reed-Sternberg cells from some patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, most commonly in those with mixed-cellularity disease.[14] In children and adolescents with intermediate-risk Hodgkin lymphoma, EBV DNA in cell-free blood correlated with the presence of EBV in the tumor; EBV DNA 8 days after the initiation of therapy predicted an inferior event-free survival (EFS).[14]

The incidence of EBV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma also shows the following distinct epidemiological features:

- Developing countries. The incidence of EBV tumor cell positivity for Hodgkin lymphoma in developed countries ranges from 15% to 25% in adolescents and young adults.[15-17] A high incidence of mixed-cellularity histology in childhood Hodgkin lymphoma is seen in developing countries, and these cases are generally EBV positive (approximately 80%).[18]

EBV serologic status is not a prognostic factor for failure-free survival in young adult patients with Hodgkin lymphoma,[15-17,19,20] but plasma EBV DNA has been associated with an inferior outcome in adults.[21] However, this is not the case in children, with better outcomes described for intermediate-risk patients with higher levels of EBV DNA at diagnosis,[14] which also correlates with better outcomes for patients with mixed-cellularity disease treated with dose-dense chemotherapy (ABVE-PC [doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, and cyclophosphamide]). Patients with a previous history of serologically confirmed infectious mononucleosis have a fourfold increased risk of developing EBV-positive Hodgkin lymphoma; these patients are not at increased risk of developing EBV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma.[22]

Immunodeficiency and Hodgkin lymphoma

Among individuals with immunodeficiency, the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma is increased,[23] although the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is even higher.

Characteristics of Hodgkin lymphoma presenting in the context of immunodeficiency are as follows:

- Hodgkin lymphoma usually occurs at a younger age and with histologies other than nodular sclerosing in patients with primary immunodeficiencies.[23]

- The risk of Hodgkin lymphoma increases as much as 50-fold over the general population in patients with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome.[24]

- Compared with the general population, the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma is increased in recipients of solid organ transplant who are maintained on chronic immunosuppressive medications.[27]

- Hodgkin lymphoma is the second most common cancer type in children who have undergone solid organ transplant.[28]

Clinical Presentation

The following presenting features of Hodgkin lymphoma result from direct or indirect effects of nodal or extranodal involvement and/or constitutional symptoms related to cytokine release from Reed-Sternberg cells and cell signaling within the tumor microenvironment:[29]

- Approximately 80% of patients present with painless adenopathy, most commonly involving the supraclavicular or cervical area.

- Mediastinal disease is present in about 75% of adolescents and young adults and may be asymptomatic. In contrast, only about 35% of young children with Hodgkin lymphoma have mediastinal involvement, reflecting the greater prevalence of mixed-cellularity and lymphocyte-predominant histology versus nodular-sclerosing histology in this age cohort.

- Three specific constitutional symptoms (B symptoms) that have been correlated with prognosis—unexplained fever (temperature above 38.0°C orally), unexplained weight loss (10% of body weight within the 6 months preceding diagnosis), and drenching night sweats—are commonly used to assign risk in clinical trials.[32]

- Female patients with large mediastinal masses and B symptoms are most likely to present with pericardial effusions.[33][Level of evidence: 3iiC]

Fifteen percent to 20% of patients will have noncontiguous extranodal involvement (stage IV). The most common sites of extranodal involvement are the lung, liver, bones, and bone marrow.[30,31]

Prognostic Factors

As the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma improved, factors associated with outcome became more difficult to identify. Several factors, however, continue to influence the success and choice of therapy. These factors are interrelated in the sense that disease stage, bulk, and biologic aggressiveness are frequently collinear.

Pretreatment factors

Pretreatment factors associated with an adverse outcome in one or more studies include the following:

- Presence of a pericardial effusion.[33][Level of evidence: 3iiC]

- Presence of a pleural effusion.[36][Level of evidence: 2A]

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.[37]

- Leukocytosis (white blood cell count of 11,500/mm3 or higher).[34]

- Anemia (hemoglobin lower than 11.0 g/dL).[34]

- Hypoalbuminemia.[35]

Prognostic factors identified in selected multi-institutional studies include the following:

- In the Society for Paediatric Oncology and Haematology (Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie [GPOH]) GPOH-95 study, B symptoms, histology, and male sex were adverse prognostic factors for EFS on multivariate analysis.[31]

- In 320 children with clinically staged Hodgkin lymphoma treated in the Stanford-St. Jude-Dana Farber Cancer Institute consortium, male sex; stage IIB, IIIB, or IV disease; white blood cell count of 11,500/mm3 or higher; and hemoglobin lower than 11.0 g/dL were significant prognostic factors for inferior disease-free survival and overall survival (OS). Prognosis was also associated with the number of adverse factors.[34]

- In the CCG-5942 study, the combination of B symptoms and bulky disease was associated with an inferior outcome.[30]

- Factors associated with adverse outcome, many of which are collinear, were evaluated by multivariable analysis using the COG trial AHOD0031 (NCT00025259) for children with intermediate-risk Hodgkin lymphoma. This study enrolled 1,734 patients. The most robust predictors of outcome in this homogeneously treated cohort were stage IV disease, fever, a large mediastinal mass, and low albumin (<3.4 g/dL). The Childhood Hodgkin International Prognostic Score, highly predictive of EFS, was derived by giving a point for each adverse factor;[35] however, it requires further prospective validation.

- Pleural effusions have been shown to be an adverse prognostic finding in patients treated for low-stage Hodgkin lymphoma.[36][Level of evidence: 2A] The risk of relapse was 25% in patients with an effusion, as opposed to less than 15% in patients without an effusion. Patients with effusions were more often older (15 years vs. 14 years) and had nodular-sclerosing histology.

A single-institution study showed that African American patients had a higher relapse rate than did white patients, but OS was similar.[40] A Children’s Oncology Group (COG) analysis showed no difference in EFS by race or ethnicity. However, compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanic and non-Hispanic black children had an inferior OS because of an increased postrelapse mortality rate.[41][Level of evidence: 1iiA]

Response to initial chemotherapy

The rapidity of response to initial cycles of chemotherapy also appears to be prognostically important.[38,39,42] Response evaluation in previous generations of trials relied on computed tomography and gallium uptake; more recent trials have employed positron emission tomography (PET) scanning to assess early response in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma.[43] Fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose PET avidity after two cycles of chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma in adults has been shown to predict treatment failure and progression-free survival.[44-46] Reduction in PET avidity after one cycle of chemotherapy was associated with a favorable EFS outcome in children with limited-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma.[37] Additional studies in children are ongoing to assess the role of early PET-based response in modifying therapy and predicting outcome.

Prognostic factors will continue to change because of risk stratification and choice of therapy, with parameters such as disease stage, bulk, systemic symptomatology, and early response to chemotherapy used to stratify therapeutic assignment.

References

- Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014.

- Ries LAG, Harkins D, Krapcho M, et al.: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2003. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute, 2006. Also available online. Last accessed June 08, 2020.

- Macfarlane GJ, Evstifeeva T, Boyle P, et al.: International patterns in the occurrence of Hodgkin's disease in children and young adult males. Int J Cancer 61 (2): 165-9, 1995.

- Grufferman S, Delzell E: Epidemiology of Hodgkin's disease. Epidemiol Rev 6: 76-106, 1984.

- Ries LA, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, et al., eds.: SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1973-1995. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute, 1998. Also available online. Last accessed June 08, 2020.

- Percy CL, Smith MA, Linet M, et al.: Lymphomas and reticuloendothelial neoplasms. In: Ries LA, Smith MA, Gurney JG, et al., eds.: Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, 1999. NIH Pub.No. 99-4649, pp 35-50. Also available online. Last accessed August 07, 2020.

- Chang ET, Montgomery SM, Richiardi L, et al.: Number of siblings and risk of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13 (7): 1236-43, 2004.

- Rudant J, Orsi L, Monnereau A, et al.: Childhood Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and factors related to the immune system: the Escale Study (SFCE). Int J Cancer 129 (9): 2236-47, 2011.

- Westergaard T, Melbye M, Pedersen JB, et al.: Birth order, sibship size and risk of Hodgkin's disease in children and young adults: a population-based study of 31 million person-years. Int J Cancer 72 (6): 977-81, 1997.

- Crump C, Sundquist K, Sieh W, et al.: Perinatal and family risk factors for Hodgkin lymphoma in childhood through young adulthood. Am J Epidemiol 176 (12): 1147-58, 2012.

- Linabery AM, Erhardt EB, Richardson MR, et al.: Family history of cancer and risk of pediatric and adolescent Hodgkin lymphoma: A Children's Oncology Group study. Int J Cancer 137 (9): 2163-74, 2015.

- Kharazmi E, Fallah M, Pukkala E, et al.: Risk of familial classical Hodgkin lymphoma by relationship, histology, age, and sex: a joint study from five Nordic countries. Blood 126 (17): 1990-5, 2015.

- Punnett A, Tsang RW, Hodgson DC: Hodgkin lymphoma across the age spectrum: epidemiology, therapy, and late effects. Semin Radiat Oncol 20 (1): 30-44, 2010.

- Welch JJG, Schwartz CL, Higman M, et al.: Epstein-Barr virus DNA in serum as an early prognostic marker in children and adolescents with Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv 1 (11): 681-684, 2017.

- Claviez A, Tiemann M, Lüders H, et al.: Impact of latent Epstein-Barr virus infection on outcome in children and adolescents with Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 23 (18): 4048-56, 2005.

- Lee JH, Kim Y, Choi JW, et al.: Prevalence and prognostic significance of Epstein-Barr virus infection in classical Hodgkin's lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Arch Med Res 45 (5): 417-31, 2014.

- Jarrett RF, Stark GL, White J, et al.: Impact of tumor Epstein-Barr virus status on presenting features and outcome in age-defined subgroups of patients with classic Hodgkin lymphoma: a population-based study. Blood 106 (7): 2444-51, 2005.

- Chabay PA, Barros MH, Hassan R, et al.: Pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma in 2 South American series: a distinctive epidemiologic pattern and lack of association of Epstein-Barr virus with clinical outcome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 30 (4): 285-91, 2008.

- Armstrong AA, Alexander FE, Cartwright R, et al.: Epstein-Barr virus and Hodgkin's disease: further evidence for the three disease hypothesis. Leukemia 12 (8): 1272-6, 1998.

- Herling M, Rassidakis GZ, Vassilakopoulos TP, et al.: Impact of LMP-1 expression on clinical outcome in age-defined subgroups of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 107 (3): 1240; author reply 1241, 2006.

- Kanakry JA, Li H, Gellert LL, et al.: Plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA predicts outcome in advanced Hodgkin lymphoma: correlative analysis from a large North American cooperative group trial. Blood 121 (18): 3547-53, 2013.

- Hjalgrim H, Askling J, Rostgaard K, et al.: Characteristics of Hodgkin's lymphoma after infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med 349 (14): 1324-32, 2003.

- Robison LL, Stoker V, Frizzera G, et al.: Hodgkin's disease in pediatric patients with naturally occurring immunodeficiency. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 9 (2): 189-92, 1987.

- Straus SE, Jaffe ES, Puck JM, et al.: The development of lymphomas in families with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome with germline Fas mutations and defective lymphocyte apoptosis. Blood 98 (1): 194-200, 2001.

- Biggar RJ, Jaffe ES, Goedert JJ, et al.: Hodgkin lymphoma and immunodeficiency in persons with HIV/AIDS. Blood 108 (12): 3786-91, 2006.

- Biggar RJ, Frisch M, Goedert JJ: Risk of cancer in children with AIDS. AIDS-Cancer Match Registry Study Group. JAMA 284 (2): 205-9, 2000.

- Knight JS, Tsodikov A, Cibrik DM, et al.: Lymphoma after solid organ transplantation: risk, response to therapy, and survival at a transplantation center. J Clin Oncol 27 (20): 3354-62, 2009.

- Yanik EL, Smith JM, Shiels MS, et al.: Cancer Risk After Pediatric Solid Organ Transplantation. Pediatrics 139 (5): , 2017.

- Steidl C, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD: Molecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin's lymphoma: increasing evidence of the importance of the microenvironment. J Clin Oncol 29 (14): 1812-26, 2011.

- Nachman JB, Sposto R, Herzog P, et al.: Randomized comparison of low-dose involved-field radiotherapy and no radiotherapy for children with Hodgkin's disease who achieve a complete response to chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 20 (18): 3765-71, 2002.

- Rühl U, Albrecht M, Dieckmann K, et al.: Response-adapted radiotherapy in the treatment of pediatric Hodgkin's disease: an interim report at 5 years of the German GPOH-HD 95 trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 51 (5): 1209-18, 2001.

- Gobbi PG, Cavalli C, Gendarini A, et al.: Reevaluation of prognostic significance of symptoms in Hodgkin's disease. Cancer 56 (12): 2874-80, 1985.

- Marks LJ, McCarten KM, Pei Q, et al.: Pericardial effusion in Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group AHOD0031 protocol. Blood 132 (11): 1208-1211, 2018.

- Smith RS, Chen Q, Hudson MM, et al.: Prognostic factors for children with Hodgkin's disease treated with combined-modality therapy. J Clin Oncol 21 (10): 2026-33, 2003.

- Schwartz CL, Chen L, McCarten K, et al.: Childhood Hodgkin International Prognostic Score (CHIPS) Predicts event-free survival in Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64 (4): , 2017.

- McCarten KM, Metzger ML, Drachtman RA, et al.: Significance of pleural effusion at diagnosis in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from Children's Oncology Group protocol AHOD0031. Pediatr Radiol 48 (12): 1736-1744, 2018.

- Keller FG, Castellino SM, Chen L, et al.: Results of the AHOD0431 trial of response adapted therapy and a salvage strategy for limited stage, classical Hodgkin lymphoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer 124 (15): 3210-3219, 2018.

- Landman-Parker J, Pacquement H, Leblanc T, et al.: Localized childhood Hodgkin's disease: response-adapted chemotherapy with etoposide, bleomycin, vinblastine, and prednisone before low-dose radiation therapy-results of the French Society of Pediatric Oncology Study MDH90. J Clin Oncol 18 (7): 1500-7, 2000.

- Friedman DL, Chen L, Wolden S, et al.: Dose-intensive response-based chemotherapy and radiation therapy for children and adolescents with newly diagnosed intermediate-risk hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group Study AHOD0031. J Clin Oncol 32 (32): 3651-8, 2014.

- Metzger ML, Castellino SM, Hudson MM, et al.: Effect of race on the outcome of pediatric patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 26 (8): 1282-8, 2008.

- Kahn JM, Kelly KM, Pei Q, et al.: Survival by Race and Ethnicity in Pediatric and Adolescent Patients With Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 37 (32): 3009-3017, 2019.

- Weiner MA, Leventhal B, Brecher ML, et al.: Randomized study of intensive MOPP-ABVD with or without low-dose total-nodal radiation therapy in the treatment of stages IIB, IIIA2, IIIB, and IV Hodgkin's disease in pediatric patients: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 15 (8): 2769-79, 1997.

- Ilivitzki A, Radan L, Ben-Arush M, et al.: Early interim FDG PET/CT prediction of treatment response and prognosis in pediatric Hodgkin disease-added value of low-dose CT. Pediatr Radiol 43 (1): 86-92, 2013.

- Hutchings M, Loft A, Hansen M, et al.: FDG-PET after two cycles of chemotherapy predicts treatment failure and progression-free survival in Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 107 (1): 52-9, 2006.

- Gallamini A, Hutchings M, Rigacci L, et al.: Early interim 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography is prognostically superior to international prognostic score in advanced-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma: a report from a joint Italian-Danish study. J Clin Oncol 25 (24): 3746-52, 2007.

- Dann EJ, Bar-Shalom R, Tamir A, et al.: Risk-adapted BEACOPP regimen can reduce the cumulative dose of chemotherapy for standard and high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma with no impairment of outcome. Blood 109 (3): 905-9, 2007.

Cellular Classification and Biologic Correlates of Childhood Hodgkin Lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by a variable number of characteristic multinucleated giant cells (Reed-Sternberg cells) or large mononuclear cell variants (lymphocytic and histiocytic cells) in a background of inflammatory cells consisting of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, epithelioid histiocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, plasma cells, and fibroblasts. The inflammatory cells are present in different proportions depending on the histologic subtype. It has been conclusively shown that Reed-Sternberg cells and/or lymphocytic and histiocytic cells represent a clonal population. Almost all cases of Hodgkin lymphoma arise from germinal center B cells.[1,2]

The histologic features and clinical symptoms of Hodgkin lymphoma have been attributed to the numerous cytokines, chemokines, and products of the tumor necrosis factor receptors (TNF-R) family secreted by the Reed-Sternberg cells and cell signaling within the tumor microenvironment.[3-5]

The hallmark of Hodgkin lymphoma is the Reed-Sternberg cell and its variants,[6] which have the following features:

- The Reed-Sternberg cell is a binucleated or multinucleated giant cell with a bilobed nucleus and two large nucleoli that give a characteristic owl's eye appearance.[6]

- The malignant Reed-Sternberg cell comprises only about 1% of the abundant reactive cellular infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, granulocytes, and eosinophils in involved specimens.[6]

- In nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, the Reed-Sternberg cells are usually mononuclear with a markedly convoluted and lobated nucleus (popcorn cells). Also known as lymphocytic and histiocytic cells, this Reed-Sternberg–cell variant does not express CD30, but does express CD20, suggesting that it is biologically distinct from other subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Most cases of classical Hodgkin lymphoma are characterized by expression of TNF-R and their ligands, as well as an unbalanced production of T helper lymphocytes type 2 (Th2) cytokines and chemokines. Activation of TNF-R results in constitutive activation of nuclear factor kappa B in Reed-Sternberg cells, which may prevent apoptosis and provide a survival advantage.[10]

Hodgkin lymphoma can be divided into the following two broad pathologic classes:[13,14]

Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma is divided into four subtypes. These subtypes are defined according to the number of Reed-Sternberg cells, characteristics of the inflammatory milieu, and the presence or absence of fibrosis.

Characteristics of the four histological subtypes of classical Hodgkin lymphoma include the following:

- Lymphocyte-rich Hodgkin lymphoma. Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma may have a nodular appearance, but immunophenotypic analysis allows distinction between this form of Hodgkin lymphoma and nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma.[15] Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma cells express CD15 and CD30.

- Nodular-sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma. Nodular-sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma histology accounts for approximately 80% of Hodgkin lymphoma cases in older children and adolescents but only 55% of cases in younger children in the United States.[16]This subtype is distinguished by the presence of collagenous bands that divide the lymph node into nodules, which often contain a Reed-Sternberg cell variant called the lacunar cell. Transforming growth factor-beta may be responsible for the fibrosis in the nodular-sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma subtype.A study of over 600 patients with nodular-sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma from three different university hospitals in the United States showed that two haplotypes in the HLA class II region correlated with a 70% increased risk of developing nodular-sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma.[17] Another haplotype was associated with a 60% decreased risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma. It is hypothesized that these haplotypes are associated with atypical immune responses that predispose to Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Mixed-cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma. Mixed-cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma is more common in young children than in adolescents and adults, with mixed-cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma accounting for approximately 20% of cases in children younger than 10 years, but only approximately 9% of older children and adolescents aged 10 to 19 years in the United States.[16]Reed-Sternberg cells are frequent in a background of abundant normal reactive cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and histiocytes). Interleukin-5 may be responsible for the eosinophilia in mixed-cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma. This subtype can be difficult to distinguish from non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma. Lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma is rare in children. It is common in adult patients with HIV.This subtype is characterized by the presence of numerous large, bizarre malignant cells, many Reed-Sternberg cells, and few lymphocytes. Diffuse fibrosis and necrosis are common. Many cases previously diagnosed as lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma are now recognized as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, or nodular-sclerosing classical Hodgkin lymphoma with lymphocyte depletion.[18]

Nodular Lymphocyte-Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma

The frequency of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma in the pediatric population ranges from 5% to 10% in different studies, with a higher frequency in children younger than 10 years than in children aged 10 to 19 years.[16] Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is most common in males younger than 18 years.[19,20]

Characteristics of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma include the following:

- Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by molecular and immunophenotypic evidence of B-lineage differentiation with the following distinctive features:

- -

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by large cells with multilobed nuclei, referred to as popcorn cells. These cells express B-cell antigens, such as CD19, CD20, CD22, and CD79A, and are negative for CD15 and may or may not express CD30.[21]

- -

The OCT2 and BOB1 oncogenes are both expressed in nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; they are not expressed in the cells of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma.[22]

- -

Reliable discrimination from non-Hodgkin lymphoma is problematic in diffuse subtypes with lymphocytic and histiocytic cells set against a diffuse background of reactive T cells.[23]

- -

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma can be difficult to distinguish from progressive transformation of germinal centers and/or T-cell–rich B-cell lymphoma.[24]

- -

Histologic and immunophenotypic variants (including CD30 and immunoglobulin D expression) may impact event-free survival.[25]

- Pediatric patients (aged <20 years) have better outcomes than do adult patients, even when controlled for other prognostic factors.[20] Chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy produce excellent long-term progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; however, radiation therapy alone should not be considered for prepubescent patients because the evidence-based doses necessary for tumor control are associated with musculoskeletal impairment. When radiation is administered with chemotherapy, lower radiation doses are effective. Late recurrences have been reported up to 10 years after initial therapy.[26,27]; [28][Level of evidence: 2A]

- Deaths observed among individuals with nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma are more frequently related to treatment complications and/or the development of subsequent neoplasms (including non-Hodgkin lymphoma) than in refractory disease, underscoring the importance of judicious use of chemotherapy and radiation therapy at initial presentation and after recurrent disease.[26,27]

References

- Bräuninger A, Schmitz R, Bechtel D, et al.: Molecular biology of Hodgkin's and Reed/Sternberg cells in Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int J Cancer 118 (8): 1853-61, 2006.

- Mathas S: The pathogenesis of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma: a model for B-cell plasticity. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 21 (5): 787-804, 2007.

- Re D, Küppers R, Diehl V: Molecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 23 (26): 6379-86, 2005.

- Steidl C, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD: Molecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin's lymphoma: increasing evidence of the importance of the microenvironment. J Clin Oncol 29 (14): 1812-26, 2011.

- Diefenbach C, Steidl C: New strategies in Hodgkin lymphoma: better risk profiling and novel treatments. Clin Cancer Res 19 (11): 2797-803, 2013.

- Küppers R, Schwering I, Bräuninger A, et al.: Biology of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Oncol 13 (Suppl 1): 11-8, 2002.

- Portlock CS, Donnelly GB, Qin J, et al.: Adverse prognostic significance of CD20 positive Reed-Sternberg cells in classical Hodgkin's disease. Br J Haematol 125 (6): 701-8, 2004.

- von Wasielewski R, Mengel M, Fischer R, et al.: Classical Hodgkin's disease. Clinical impact of the immunophenotype. Am J Pathol 151 (4): 1123-30, 1997.

- Tzankov A, Zimpfer A, Pehrs AC, et al.: Expression of B-cell markers in classical Hodgkin lymphoma: a tissue microarray analysis of 330 cases. Mod Pathol 16 (11): 1141-7, 2003.

- Skinnider BF, Mak TW: The role of cytokines in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 99 (12): 4283-97, 2002.

- Steidl C, Shah SP, Woolcock BW, et al.: MHC class II transactivator CIITA is a recurrent gene fusion partner in lymphoid cancers. Nature 471 (7338): 377-81, 2011.

- Green MR, Monti S, Rodig SJ, et al.: Integrative analysis reveals selective 9p24.1 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 116 (17): 3268-77, 2010.

- Pileri SA, Ascani S, Leoncini L, et al.: Hodgkin's lymphoma: the pathologist's viewpoint. J Clin Pathol 55 (3): 162-76, 2002.

- Harris NL: Hodgkin's lymphomas: classification, diagnosis, and grading. Semin Hematol 36 (3): 220-32, 1999.

- Anagnostopoulos I, Hansmann ML, Franssila K, et al.: European Task Force on Lymphoma project on lymphocyte predominance Hodgkin disease: histologic and immunohistologic analysis of submitted cases reveals 2 types of Hodgkin disease with a nodular growth pattern and abundant lymphocytes. Blood 96 (5): 1889-99, 2000.

- Bazzeh F, Rihani R, Howard S, et al.: Comparing adult and pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program, 1988-2005: an analysis of 21 734 cases. Leuk Lymphoma 51 (12): 2198-207, 2010.

- Cozen W, Li D, Best T, et al.: A genome-wide meta-analysis of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma identifies risk loci at 6p21.32. Blood 119 (2): 469-75, 2012.

- Slack GW, Ferry JA, Hasserjian RP, et al.: Lymphocyte depleted Hodgkin lymphoma: an evaluation with immunophenotyping and genetic analysis. Leuk Lymphoma 50 (6): 937-43, 2009.

- Hall GW, Katzilakis N, Pinkerton CR, et al.: Outcome of children with nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma - a Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group report. Br J Haematol 138 (6): 761-8, 2007.

- Gerber NK, Atoria CL, Elkin EB, et al.: Characteristics and outcomes of patients with nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma versus those with classical Hodgkin lymphoma: a population-based analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 92 (1): 76-83, 2015.

- Shankar A, Daw S: Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents--a comprehensive review of biology, clinical course and treatment options. Br J Haematol 159 (3): 288-98, 2012.

- Stein H, Marafioti T, Foss HD, et al.: Down-regulation of BOB.1/OBF.1 and Oct2 in classical Hodgkin disease but not in lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin disease correlates with immunoglobulin transcription. Blood 97 (2): 496-501, 2001.

- Boudová L, Torlakovic E, Delabie J, et al.: Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma with nodules resembling T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: differential diagnosis between nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma and T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma. Blood 102 (10): 3753-8, 2003.

- Kraus MD, Haley J: Lymphocyte predominance Hodgkin's disease: the use of bcl-6 and CD57 in diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 24 (8): 1068-78, 2000.

- Untanu RV, Back J, Appel B, et al.: Variant histology, IgD and CD30 expression in low-risk pediatric nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65 (1): , 2018.

- Chen RC, Chin MS, Ng AK, et al.: Early-stage, lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma: patient outcomes from a large, single-institution series with long follow-up. J Clin Oncol 28 (1): 136-41, 2010.

- Jackson C, Sirohi B, Cunningham D, et al.: Lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma--clinical features and treatment outcomes from a 30-year experience. Ann Oncol 21 (10): 2061-8, 2010.

- Appel BE, Chen L, Buxton AB, et al.: Minimal Treatment of Low-Risk, Pediatric Lymphocyte-Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Report From the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 34 (20): 2372-9, 2016.

Diagnosis and Staging Information for Childhood Hodgkin Lymphoma

Staging and evaluation of disease status is undertaken at diagnosis and performed again early in the course of chemotherapy and at the end of chemotherapy.

Diagnostic and Staging Evaluation

The diagnostic and staging evaluation is a critical determinant in the selection of treatment. Initial evaluation of the child with Hodgkin lymphoma includes the following:

- History of systemic symptoms (detailed).

- Physical examination.

- Laboratory studies, including complete blood count, chemistry panel with albumin, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

- Anatomic imaging, including chest x-ray and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis. MRI and positron emission tomography (PET)–MRI provide the advantage of limiting radiation exposure.[1]

- Functional imaging, including PET scan.

Systemic symptoms

The following three specific constitutional symptoms (B symptoms) correlate with prognosis and are considered in assignment of stage:

- Unexplained fever with temperatures above 38.0°C orally.

- Unexplained weight loss of 10% within the 6 months preceding diagnosis.

- Drenching night sweats.

Additional Hodgkin-associated constitutional symptoms without prognostic significance include the following:

- Pruritus.

- Alcohol-induced nodal pain.

Physical examination

- All node-bearing areas, including the Waldeyer ring, should be assessed by careful physical examination.

- Enlarged nodes should be measured to establish a baseline for evaluation of therapy response.

Laboratory studies

- Hematological and chemical blood parameters (e.g., albumin) show nonspecific changes that may correlate with disease extent.

- Abnormalities of peripheral blood counts may include neutrophilic leukocytosis, lymphopenia, eosinophilia, and monocytosis.

- Acute-phase reactants such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, if abnormal at diagnosis, may be useful in follow-up evaluation.[2]

Anatomic imaging

Anatomic information from CT or MRI is complemented by PET functional imaging, which is sensitive in determining initial sites of involvement, particularly in sites too small to be considered clearly involved by CT or MRI criteria. Collaboration across international groups to harmonize definitions is ongoing.[3]

Definition of bulky disease

Historically, the presence of bulky disease, especially mediastinal bulk, predicted an increased risk of local failure and resulted in the incorporation of bulk as an important factor in treatment assignment. The definition of bulk has varied across pediatric protocols and evolved over time with advances in diagnostic imaging technology.[3]

The criteria for bulky mediastinal and nonmediastinal disease are as follows:

- Mediastinal. In North American protocols, the posteroanterior chest radiograph remains important because the criterion for bulky mediastinal lymphadenopathy is defined by the ratio of the diameter of the mediastinal lymph node mass to the maximal diameter of the rib cage on an upright chest radiograph; a ratio of 33% or higher is considered bulky. In contrast, the EuroNet-Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma Group defines mediastinal bulk by the volume of the largest contiguous lymph node mass being 200 mL or more on CT. These two definitions differ from the recently published consensus guidelines from the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Group (Lugano), where bulk is described as a mass 10 cm or larger unidimensionally on CT.[4]

- Nonmediastinal. The criteria for bulky peripheral, nonmediastinal lymphadenopathy have also varied over the years in cooperative group study protocols, and this disease characteristic has not been consistently used for treatment stratification. In contemporary U.S. protocols, bulky peripheral lymphadenopathy is defined as greater than 6 cm, with aggregates measured transversely or cranial-caudal. In EuroNet protocols, peripheral adenopathy is again defined as a volume of greater than 200 mL, which is generally larger than a 6 cm unidimensional mass.

Criteria for lymphomatous involvement by CT or MRI

Defining strict CT or MRI size criteria for lymphomatous nodal involvement is complicated by several factors, such as size overlap between what proves to be benign reactive hyperplasia versus malignant lymphadenopathy, the implication of nodal clusters, and obliquity of node orientation to the scan plane. Additional difficulties more specific to children include greater variability of normal nodal size and the frequent occurrence of reactive hyperplasia.

General concepts to consider in regard to defining lymphomatous involvement by CT or MRI include the following:

- Contiguous nodal clustering or matting is highly suggestive of lymphomatous involvement.

- Any focal mass lesion large enough to characterize in a visceral organ is considered lymphomatous involvement unless the imaging characteristics indicate an alternative etiology.

- Criteria for nodal involvement may vary by cooperative group or protocol.[3]

- -

Children's Oncology Group (COG) and EuroNet protocols consider lymph nodes abnormal if the long axis is greater than 2 cm, regardless of the short axis and PET avidity. Lymph nodes with a long axis measuring between 1 cm and 2 cm are only considered abnormal if they are part of a conglomerate of nodes and are fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET positive.

- -

In the Society for Paediatric Oncology and Haematology (Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie [GPOH]) GPOH-HD-2002 study, nodal involvement was defined as node size greater than 2 cm in largest diameter. The node was not involved if it was less than 1 cm and was considered questionable if it was between 1 cm and 2 cm. The decision on involvement was then made on the basis of additional clinical evidence.[5]

- -

In an analysis of 47,828 imaging measurements from 2,983 individual patients with adult and pediatric lymphoma enrolled in ten multicenter clinical trials, a single dimension measurement of 15 mm or more constituted involvement.[6]

Functional imaging

The recommended functional imaging procedure for initial staging is PET, using the radioactive glucose analog, 18F-FDG.[7,8] 18F-FDG PET identifies areas of tumor with increased metabolic activity, specifically anaerobic glycolysis. PET-CT, which integrates functional and anatomic tumor characteristics, is often used for staging and monitoring of pediatric patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Residual or persistent 18F-FDG avidity has been correlated with poor prognosis and the need for additional therapy in posttreatment evaluation.[9-12]; [13][Level of evidence: 2Diii]

General concepts to consider in regard to defining lymphomatous involvement by 18F-FDG PET include the following:

- Concordance between PET and CT data is generally high for nodal regions, but may be significantly lower for extranodal sites. In one study specifically analyzing pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma patients, assessment of initial staging comparing PET and CT data demonstrated concordance of approximately 86% overall. Concordance rates were significantly lower for the spleen, lung nodules, bone/bone marrow, and pleural and pericardial effusions.[14] A meta-analysis of nine clinical studies showed that PET-CT achieved high sensitivity (96.9%) and high specificity (99.7%) in detecting bone marrow involvement in newly diagnosed patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, with focal involvement highly predictive of bone marrow involvement.[15,16]

- Staging criteria using PET and CT scan information is protocol dependent, but generally areas of PET positivity that do not correspond to an anatomic lesion by clinical examination or CT scan size criteria should be disregarded in staging, with the possible exception of focally PET-positive bone marrow findings.

- A suspected anatomic lesion that is PET negative should not be considered involved unless proven by biopsy.

18F-FDG PET has limitations in the pediatric setting. Tracer avidity may be seen in a variety of nonmalignant conditions including thymic rebound commonly observed after completion of lymphoma therapy. 18F-FDG avidity in normal tissues, such as brown fat in the neck, may confound interpretation of the presence of nodal involvement by lymphoma.[7]

Visual PET criteria are scored according to uptake involved by lymphoma from the Deauville 5-point scale, from 1 to 5, as described in Table 2. The COG and EuroNet definitions of PET response of lymph nodes or nodal masses are described in Table 3.

Table

Table 2. Deauville Score Criteria.

Table

Table 3. Children's Oncology Group and EuroNet Definition of PET Response of Lymph Node or Nodal Masses.

Establishing the Diagnosis of Hodgkin Lymphoma

After a careful physiologic and radiographic evaluation of the patient, the least invasive procedure should be used to establish the diagnosis of lymphoma. However, this should not be interpreted to mean that a needle biopsy is the optimal methodology. Small fragments of lymphoma tissue are often inadequate for diagnosis, resulting in the need for second procedures that delay the diagnosis.

If possible, the diagnosis should be established by biopsy of one or more peripheral lymph nodes. The likelihood of obtaining sufficient tissue should be carefully considered when selecting a biopsy procedure. Other issues to consider in choosing the diagnostic approach to lymph node biopsy include the following:

- Type of biopsy procedure.

- -

Aspiration cytology alone is not recommended because of the lack of stromal tissue, the small number of cells present in the specimen, and the difficulty of classifying Hodgkin lymphoma into one of the subtypes.

- -

An image-guided biopsy may be used to obtain diagnostic tissue from intra-thoracic or intra-abdominal lymph nodes. On the basis of the involved sites of disease, alternative procedures that may be considered include thoracoscopy, mediastinoscopy, and laparoscopy. Thoracotomy or laparotomy is rarely needed to access diagnostic tissue.

- -

Because bone marrow involvement is relatively rare in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma patients, bilateral bone marrow biopsy should be performed only in patients with advanced disease (stage III or stage IV) and/or B symptoms.[18]

In support of this, a meta-analysis of nine clinical studies including both pediatric and adult patients showed that PET-CT achieved high sensitivity (96.9%) and high specificity (99.7%) in detecting bone marrow involvement in newly diagnosed patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.[15] (Refer to the Stage Information for Adult HL section in the PDQ summary on Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment for more information.) In a consensus statement based on these studies, this group no longer recommends bone marrow biopsy in the initial evaluation of adults with Hodgkin lymphoma, with PET-CT being used instead to identify bone marrow involvement.[4]

- Procedure-related complications.

- -

Patients with large mediastinal masses are at risk of cardiac or respiratory arrest during general anesthesia or heavy sedation.[19] After careful planning with anesthesia, peripheral lymph node biopsy or image-guided core-needle biopsy of mediastinal lymph nodes may be feasible using light sedation and local anesthesia before proceeding to more invasive procedures.

- -

If airway compromise precludes the performance of a diagnostic operative procedure, preoperative treatment with steroids or low-dose, localized radiation therapy should be considered, although that can be technically difficult if the patient cannot recline. Since preoperative treatment may affect the ability to obtain an accurate tissue diagnosis, a diagnostic biopsy should be obtained as soon as the risks associated with general anesthesia or heavy sedation are alleviated.

Ann Arbor Staging Classification for Hodgkin Lymphoma

Stage is determined by anatomic evidence of disease using CT or MRI scanning in conjunction with functional imaging. The staging classification used for Hodgkin lymphoma was adopted at the Ann Arbor Conference held in 1971 [20] and revised in 1989 (refer to Table 4).[21] Staging is independent of the imaging modality used.

Table

Table 4. Ann Arbor Staging Classification for Hodgkin Lymphomaa.

Extralymphatic disease resulting from direct extension of an involved lymph node region is designated E. Extralymphatic disease can cause confusion in staging. For example, the designation E is not appropriate for cases of widespread disease or diffuse extralymphatic disease (e.g., large pleural effusion that is cytologically positive for Hodgkin lymphoma), which should be considered stage IV. If pathologic proof of noncontiguous involvement of one or more extralymphatic sites has been documented, the symbol for the site of involvement, followed by a plus sign (+), is listed.

Current practice is to assign a clinical stage on the basis of findings of the clinical evaluation; however, pathologic confirmation of noncontiguous extralymphatic involvement is strongly suggested for assignment to stage IV.

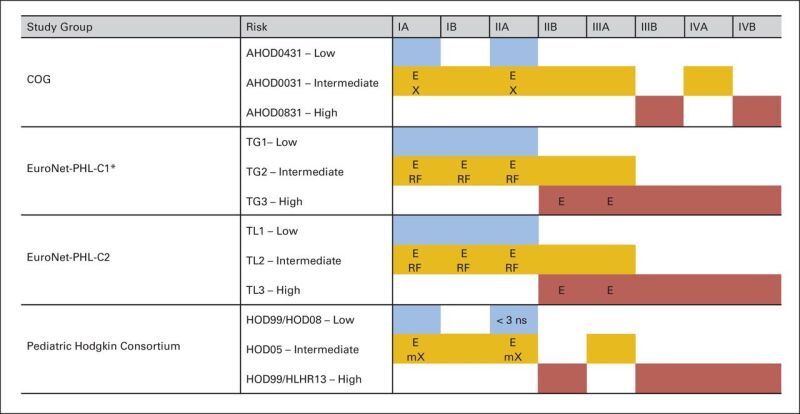

Risk Stratification

After the diagnostic and staging evaluation data are acquired, patients are further classified into risk groups for the purposes of treatment planning. The classification of patients into low-, intermediate-, or high-risk categories varies considerably among the different pediatric research groups, and often even between different studies conducted by the same group, as summarized in Figure 1.[23]

Figure 1. Variation in risk stratification across pediatric Hodgkin study groups and protocols. E, extranodal extension; X, bulky disease (peripheral >6 cm and mediastinal bulk); mX, mediastinal bulk (≥0.33 mediastinal to thoracic ratio); ns, nodal site; TG, treatment group; TL, treatment level; RF, risk factors: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥30 mm/hour and/or bulk ≥200 mL. (*) EuroNet-PHL-C1 was amended in 2012: Low-risk (TG1) patients with ESR ≥30 mm/hour and/or bulk ≥200 mL were treated in TG2 (intermediate risk). Christine Mauz-Körholz, Monika L. Metzger, Kara M. Kelly, Cindy L. Schwartz, Mauricio E. Castellanos, Karin Dieckmann, Regine Kluge, and Dieter Körholz, Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma, Journal of Clinical Oncology, volume 33, issue 27, pages 2975–2985. Reprinted with permission. © (2015) American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Although all major research groups classify patients according to clinical criteria, such as stage and presence of B symptoms, extranodal involvement, or bulky disease, comparison of outcomes across trials is further complicated because of differences in how these individual criteria are defined.[3]

Response Assessment

Further refinement of risk classification may be performed through assessment of response after initial cycles of chemotherapy or at the completion of chemotherapy.

Interim response assessment

The interim response to initial therapy, which may be assessed on the basis of volume reduction of disease, functional imaging status, or both, is an important prognostic variable in both early- and advanced-stage pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma.[24-27]; [13][Level of evidence: 2Diii]

Definitions for interim response are variable and protocol specific but can range from 2-dimensional reductions in size of greater than 50% to the achievement of a complete response with 2-dimensional reductions in size of greater than 75% or 80% or a volume reduction of greater than 95% by anatomic imaging or resolution of 18F-FDG PET avidity.[5,28,29]

The rapidity of response to early therapy has been used in risk stratification to tailor therapy in an effort to augment therapy in higher-risk patients or to reduce the late effects while maintaining efficacy.[26,27,29,30]

Results of selected trials using interim response to titrate therapy

Several studies have evaluated the use of interim response to titrate additional therapy:

- The Pediatric Oncology Group used a response-based therapy approach consisting of dose-dense ABVE-PC (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, and cyclophosphamide) for intermediate-stage and advanced-stage patients, in combination with 21 Gy involved-field radiation therapy (IFRT).[29]

- The dose-dense approach permitted reduction in chemotherapy exposure in 63% of patients who achieved a rapid early response on CT imaging after three ABVE-PC cycles.

- Five-year event-free survival (EFS) was comparable for rapid early responders (86%; treated with three cycles of ABVE-PC) and slow early responders (83%; treated with five cycles of ABVE-PC). All patients received 21 Gy of regional radiation therapy.

- The Children's Cancer Group (CCG) (CCG-59704) evaluated response-adapted therapy featuring four cycles of the dose-intensive BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone) regimen followed by a sex-tailored consolidation for pediatric patients with stages IIB, IIIB with bulky disease, and IV Hodgkin lymphoma.[30]

- For rapid early responding girls, an additional four courses of COPP/ABV (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone/doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine) (without IFRT) was given in an effort to reduce breast cancer risk.

- Rapid early responding boys received two cycles of ABVD followed by IFRT.

- Slow early responders received four additional courses of BEACOPP and IFRT.

- Rapid early response (defined by resolution of B symptoms and >70% reduction in tumor volume) was achieved by 74% of patients after four BEACOPP cycles and 5-year EFS among the cohort was 94% (median follow-up, 6.3 years).

- The COG AHOD0031 (NCT00025259), AHOD0831 (NCT01026220), and AHOD0431 (NCT00302003) trials also used interim response to titrate therapy. (Refer to the North American cooperative and consortium trial results section of this summary for more information.) The AHOD0031 trial was designed to evaluate this paradigm of care by randomly assigning patients to receive either standard or response-based therapy.

End of chemotherapy response assessment

Restaging is carried out upon the completion of all planned initial chemotherapy and may be used to determine the need for consolidative radiation therapy. Key concepts to consider include the following:

- Defining complete response. The definition of complete response may vary by cooperative group or protocol.

- -

The International Working Group (IWG) defined complete response for adults with Hodgkin lymphoma in terms of complete metabolic response as assessed by 18F-FDG PET, even when a persistent mass is present.[31] These criteria were endorsed in the Lugano Classification, with the recommendation for using a 5-point scale in assessing response.[4,32] COG protocols have adopted this approach for defining complete response.

- -

Previous studies have varied in the use of findings from clinical exam, anatomic imaging, and functional imaging to assess response. Although complete response can be defined as absence of disease by clinical examination and/or imaging studies, complete response in Hodgkin lymphoma trials is often defined by a greater than 80% reduction of disease and a change from initial positivity to negativity on functional imaging.[33] This definition is necessary in Hodgkin lymphoma because fibrotic residual disease is common, particularly in the mediastinum. In some studies, such patients are designated as having an unconfirmed complete response.

- -

The EuroNet Hodgkin lymphoma trials use a similar early response assessment definition of PET positivity, which is a Deauville score of greater than 3 after two cycles of OEPA (vincristine [Oncovin], etoposide, prednisone, doxorubicin [Adriamycin]).[34]

- -

GPOH studies use very stringent criteria for treatment group 1 (TG1) patients that includes at least 95% reduction in tumor volume or less than 2 mL residual volume on CT, as patients achieving these metrics will have radiation therapy omitted. Treatment group 2 (TG2) and treatment group 3 (TG3) patients received radiation therapy despite their potential morphologic complete response (refer to Figure 1).[5]

- -

The COG AHOD1331 (NCT02166463) high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma initial therapeutics clinical trial uses 18F-FDG PET assessment graded by a 5-point visual scale or Deauville criteria after two chemotherapy cycles to define a rapid early-responding lesion for which radiation will be omitted. A mass of any size is permitted for a complete response designation if the PET is negative. The results of using the latter criteria are not yet available; therefore, it may not be considered standard of care.

- Timing of PET scanning after completing therapy. Timing of PET scanning after completing therapy is an important issue.

- -

For patients treated with chemotherapy alone, PET scanning is ideally performed a minimum of 3 weeks after the completion of therapy, while patients whose last treatment modality was radiation therapy should not undergo PET scanning until 8 to 12 weeks postradiation.[31]

- Screening frequency and overscreening.

- -

A COG study evaluated surveillance CT and detection of relapse in intermediate-stage and advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma. Most relapses occurred within the first year after therapy and were detected based on symptoms, laboratory, or physical findings. The method of detection of late relapse, whether by imaging or clinical change, did not affect overall survival. Routine use of CT at the intervals used in this study did not improve outcome.[35] The concept of reduced frequency of imaging has been supported by other investigations.[36-38]

- -

Caution should be used in making the diagnosis of relapsed or refractory disease based solely on anatomic and functional imaging because false-positive results are not uncommon.[39-41] Consequently, pathologic confirmation of refractory or recurrent disease is recommended before modification of therapeutic plans.

References

- Afaq A, Fraioli F, Sidhu H, et al.: Comparison of PET/MRI With PET/CT in the Evaluation of Disease Status in Lymphoma. Clin Nucl Med 42 (1): e1-e7, 2017.

- Haase R, Vilser C, Mauz-Körholz C, et al.: Evaluation of the prognostic meaning of C-reactive protein (CRP) in children and adolescents with classical Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL). Klin Padiatr 224 (6): 377-81, 2012.

- Flerlage JE, Kelly KM, Beishuizen A, et al.: Staging Evaluation and Response Criteria Harmonization (SEARCH) for Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma (CAYAHL): Methodology statement. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64 (7): , 2017.

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al.: Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 32 (27): 3059-68, 2014.

- Mauz-Körholz C, Hasenclever D, Dörffel W, et al.: Procarbazine-free OEPA-COPDAC chemotherapy in boys and standard OPPA-COPP in girls have comparable effectiveness in pediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma: the GPOH-HD-2002 study. J Clin Oncol 28 (23): 3680-6, 2010.

- Younes A, Hilden P, Coiffier B, et al.: International Working Group consensus response evaluation criteria in lymphoma (RECIL 2017). Ann Oncol 28 (7): 1436-1447, 2017.

- Hudson MM, Krasin MJ, Kaste SC: PET imaging in pediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma. Pediatr Radiol 34 (3): 190-8, 2004.

- Hernandez-Pampaloni M, Takalkar A, Yu JQ, et al.: F-18 FDG-PET imaging and correlation with CT in staging and follow-up of pediatric lymphomas. Pediatr Radiol 36 (6): 524-31, 2006.

- Naumann R, Vaic A, Beuthien-Baumann B, et al.: Prognostic value of positron emission tomography in the evaluation of post-treatment residual mass in patients with Hodgkin's disease and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Haematol 115 (4): 793-800, 2001.

- Hutchings M, Loft A, Hansen M, et al.: FDG-PET after two cycles of chemotherapy predicts treatment failure and progression-free survival in Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 107 (1): 52-9, 2006.

- Lopci E, Burnelli R, Guerra L, et al.: Postchemotherapy PET evaluation correlates with patient outcome in paediatric Hodgkin's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 38 (9): 1620-7, 2011.

- Sucak GT, Özkurt ZN, Suyani E, et al.: Early post-transplantation positron emission tomography in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma is an independent prognostic factor with an impact on overall survival. Ann Hematol 90 (11): 1329-36, 2011.

- Lopci E, Mascarin M, Piccardo A, et al.: FDG PET in response evaluation of bulky masses in paediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) patients enrolled in the Italian AIEOP-LH2004 trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 46 (1): 97-106, 2019.

- Robertson VL, Anderson CS, Keller FG, et al.: Role of FDG-PET in the definition of involved-field radiation therapy and management for pediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 80 (2): 324-32, 2011.

- Adams HJ, Kwee TC, de Keizer B, et al.: Systematic review and meta-analysis on the diagnostic performance of FDG-PET/CT in detecting bone marrow involvement in newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma: is bone marrow biopsy still necessary? Ann Oncol 25 (5): 921-7, 2014.

- Cistaro A, Cassalia L, Ferrara C, et al.: Italian Multicenter Study on Accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT in Assessing Bone Marrow Involvement in Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 18 (6): e267-e273, 2018.

- Cheng G, Servaes S, Zhuang H: Value of (18)F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan versus diagnostic contrast computed tomography in initial staging of pediatric patients with lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 54 (4): 737-42, 2013.

- Simpson CD, Gao J, Fernandez CV, et al.: Routine bone marrow examination in the initial evaluation of paediatric Hodgkin lymphoma: the Canadian perspective. Br J Haematol 141 (6): 820-6, 2008.

- Anghelescu DL, Burgoyne LL, Liu T, et al.: Clinical and diagnostic imaging findings predict anesthetic complications in children presenting with malignant mediastinal masses. Paediatr Anaesth 17 (11): 1090-8, 2007.

- Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, et al.: Report of the Committee on Hodgkin's Disease Staging Classification. Cancer Res 31 (11): 1860-1, 1971.

- Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, et al.: Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol 7 (11): 1630-6, 1989.

- Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2010.

- Mauz-Körholz C, Metzger ML, Kelly KM, et al.: Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 33 (27): 2975-85, 2015.

- Kung FH, Schwartz CL, Ferree CR, et al.: POG 8625: a randomized trial comparing chemotherapy with chemoradiotherapy for children and adolescents with Stages I, IIA, IIIA1 Hodgkin Disease: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 28 (6): 362-8, 2006.

- Weiner MA, Leventhal B, Brecher ML, et al.: Randomized study of intensive MOPP-ABVD with or without low-dose total-nodal radiation therapy in the treatment of stages IIB, IIIA2, IIIB, and IV Hodgkin's disease in pediatric patients: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 15 (8): 2769-79, 1997.

- Keller FG, Castellino SM, Chen L, et al.: Results of the AHOD0431 trial of response adapted therapy and a salvage strategy for limited stage, classical Hodgkin lymphoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer 124 (15): 3210-3219, 2018.

- Friedman DL, Chen L, Wolden S, et al.: Dose-intensive response-based chemotherapy and radiation therapy for children and adolescents with newly diagnosed intermediate-risk hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group Study AHOD0031. J Clin Oncol 32 (32): 3651-8, 2014.

- Keller FG, Nachman J, Constine L: A phase III study for the treatment of children and adolescents with newly diagnosed low risk Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). [Abstract] Blood 116 (21): A-767, 2010.

- Schwartz CL, Constine LS, Villaluna D, et al.: A risk-adapted, response-based approach using ABVE-PC for children and adolescents with intermediate- and high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma: the results of P9425. Blood 114 (10): 2051-9, 2009.

- Kelly KM, Sposto R, Hutchinson R, et al.: BEACOPP chemotherapy is a highly effective regimen in children and adolescents with high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Blood 117 (9): 2596-603, 2011.

- Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al.: Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 25 (5): 579-86, 2007.

- Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, et al.: Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol 32 (27): 3048-58, 2014.

- Molnar Z, Simon Z, Borbenyi Z, et al.: Prognostic value of FDG-PET in Hodgkin lymphoma for posttreatment evaluation. Long term follow-up results. Neoplasma 57 (4): 349-54, 2010.

- Hasenclever D, Kurch L, Mauz-Körholz C, et al.: qPET - a quantitative extension of the Deauville scale to assess response in interim FDG-PET scans in lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 41 (7): 1301-8, 2014.

- Voss SD, Chen L, Constine LS, et al.: Surveillance computed tomography imaging and detection of relapse in intermediate- and advanced-stage pediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 30 (21): 2635-40, 2012.

- Rathore N, Eissa HM, Margolin JF, et al.: Pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma: are we over-scanning our patients? Pediatr Hematol Oncol 29 (5): 415-23, 2012.

- Hartridge-Lambert SK, Schöder H, Lim RC, et al.: ABVD alone and a PET scan complete remission negates the need for radiologic surveillance in early-stage, nonbulky Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer 119 (6): 1203-9, 2013.

- Friedmann AM, Wolfson JA, Hudson MM, et al.: Relapse after treatment of pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma: outcome and role of surveillance after end of therapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60 (9): 1458-63, 2013.

- Nasr A, Stulberg J, Weitzman S, et al.: Assessment of residual posttreatment masses in Hodgkin's disease and the need for biopsy in children. J Pediatr Surg 41 (5): 972-4, 2006.

- Meany HJ, Gidvani VK, Minniti CP: Utility of PET scans to predict disease relapse in pediatric patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48 (4): 399-402, 2007.

- Picardi M, De Renzo A, Pane F, et al.: Randomized comparison of consolidation radiation versus observation in bulky Hodgkin's lymphoma with post-chemotherapy negative positron emission tomography scans. Leuk Lymphoma 48 (9): 1721-7, 2007.

Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Children and Adolescents With Hodgkin Lymphoma

Historical Overview of Treatment for Hodgkin Lymphoma

Long-term survival has been achieved in children and adolescents with Hodgkin lymphoma using radiation, multiagent chemotherapy, and combined-modality therapy. In selected cases of localized lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, complete surgical resection may be curative and obviate the need for cytotoxic therapy.

Treatment options for children and adolescents with Hodgkin lymphoma include the following:

- Radiation therapy as a single modality.

- Recognition of the excess adverse effects of high-dose radiation therapy on musculoskeletal development in children motivated investigations of multiagent chemotherapy alone or with lower radiation doses (15–25.5 Gy) and reduced treatment volumes (involved-fields). It also led to the abandonment of the use of radiation as a single modality in skeletally immature children.[1-3]

- Radiation therapy alone may rarely be considered for adolescents and young adults with nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Multiagent chemotherapy as a single modality.

- The establishment of the noncross-resistant combinations of MOPP (mechlorethamine, vincristine [Oncovin], procarbazine, and prednisone) developed in the 1960s and ABVD (doxorubicin [Adriamycin], bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) developed in the 1970s made long-term survival possible for patients with advanced and unfavorable (e.g., bulky, symptomatic) Hodgkin lymphoma.[6,7]MOPP-related sequelae include a dose-related risk of infertility and subsequent myelodysplasia and leukemia.[2,8] The use of MOPP-derivative regimens substituting less leukemogenic and gonadotoxic alkylating agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide) for mechlorethamine or restricting cumulative alkylating agent dose exposure reduces this risk.[9]

- Etoposide has been incorporated into treatment regimens as an effective alternative to alkylating agents in an effort to reduce gonadal toxicity and enhance antineoplastic activity.[15]Etoposide-related sequelae include an increased risk of subsequent myelodysplasia and leukemia that appears to be rare when etoposide is used in restricted doses in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma regimens.[16]

- All of the agents in original MOPP and ABVD regimens continue to be used in contemporary pediatric treatment regimens. COPP (substituting cyclophosphamide for mechlorethamine) has almost uniformly replaced MOPP as the preferred alkylator regimen in most frontline trials. Contemporary trials have utilized procarbazine-free standard backbone regimens, such as ABVE-PC (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, and cyclophosphamide) in North America [17,18] and OEPA (vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, doxorubicin)-COPDAC (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, dacarbazine) in Europe.[19] Both of these regimens represent dose-dense regimens that use six drugs to maximize intensity without exceeding thresholds of toxicity.

- Radiation therapy and multiagent chemotherapy as a combined-modality therapy. Considerations for the use of multiagent chemotherapy alone versus combined-modality therapy include the following:

- Treatment with noncross-resistant chemotherapy alone offers advantages for children managed in centers in developing countries lacking radiation facilities and trained personnel, as well as diagnostic imaging modalities needed for clinical staging. This treatment option also avoids the potential long-term growth inhibition, organ dysfunction, and solid tumor induction associated with radiation.

- Chemotherapy-alone treatment protocols usually prescribe higher cumulative doses of alkylating agent and anthracycline chemotherapy, which may produce acute- and late-treatment morbidity from myelosuppression, cardiac toxic effects, gonadal injury, and subsequent leukemia. However, more recent trials are designed to significantly reduce these risks, especially in those with chemotherapy-responsive disease.[17]

- In general, the use of combined chemotherapy and low-dose involved-site radiation therapy (LD-ISRT) broadens the spectrum of potential toxicities, while reducing the severity of individual drug-related or radiation-related toxicities. The results of prospective and controlled randomized trials indicate that combined-modality therapy, compared with chemotherapy alone, produces a superior event-free survival (EFS). However, because of effective second-line therapy, overall survival (OS) has not differed among the groups studied.[20,21]

Contemporary Approaches to Treatment of Hodgkin Lymphoma

Contemporary treatment for pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma uses a risk-adapted and response-based paradigm that assigns the length and intensity of therapy based on disease-related factors such as stage, number of involved nodal regions, tumor bulk, the presence of B symptoms, and early response to chemotherapy by functional and anatomic imaging. Age, sex, and histological subtype may also be considered in treatment planning.

Treatment options for childhood Hodgkin lymphoma include the following:

Risk designation

Risk designation depends on favorable and unfavorable clinical features, as follows:

- Favorable clinical features. These features include localized nodal involvement in the absence of B symptoms and bulky disease. Risk factors considered in other studies include the number of involved nodal regions, the presence of hilar adenopathy, the size of peripheral lymphadenopathy, and extranodal extension.[22]

- Unfavorable clinical features. These features include the presence of B symptoms, bulky mediastinal or peripheral lymphadenopathy, extranodal extension of disease, and advanced (stages IIIB–IV) disease.[22] In most clinical trials, bulky mediastinal lymphadenopathy is designated when the ratio of the maximum measurement of mediastinal lymphadenopathy to intrathoracic cavity on an upright chest radiograph equals or exceeds 33%.Pleural effusions have been shown to be an adverse prognostic finding in patients treated for low-stage Hodgkin lymphoma.[23][Level of evidence: 2A] The risk of relapse was 25% in patients with an effusion, as opposed to less than 15% in patients without an effusion. Patients with effusions were more often older (15 years vs. 14 years) and had nodular-sclerosing histology.Localized disease (stages I, II, and IIIA) with unfavorable features may be treated similarly to advanced-stage disease in some treatment protocols or treated with therapy of intermediate intensity.[22]

Inconsistency in risk categorization across studies often makes comparison of study outcomes challenging.

Risk-adapted treatment paradigms

No single treatment approach is ideal for all pediatric and young adult patients because of the differences in age-related developmental status and sex-related sensitivity to chemotherapy toxicity.

- The general treatment strategy that is used to treat children and adolescents with Hodgkin lymphoma is chemotherapy for all patients, with or without radiation.

- -

The number of cycles and intensity of chemotherapy may be determined by the rapidity and degree of response, as is the radiation dose and volume. The primary exception to this strategy is in patients with nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma when surgical resection has been advocated for stage I disease with a single resectable node in the United States [24] and for any resectable disease in Europe.[25]

- -

Sex-based regimens consider that male patients are more vulnerable to gonadal toxicity from alkylating-agent chemotherapy and that female patients have a substantial risk of breast cancer after chest irradiation. However, the cardiovascular risk to males after chest irradiation suggests that limiting radiation exposure is also desirable in males.[26]

Ongoing trials for patients with favorable disease presentations are evaluating the effectiveness of treatment with fewer cycles of combination chemotherapy alone that limit doses of anthracyclines, alkylating agents, and radiation therapy. Contemporary trials for patients with intermediate/unfavorable disease presentations are testing whether chemotherapy and radiation therapy can be limited in patients who achieve a rapid early response to dose-intensive chemotherapy regimens; trials are also testing the efficacy of regimens integrating novel, potentially less-toxic agents such as brentuximab vedotin.

Histology-based therapy

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma

Histological subtype may direct therapy in patients with stage I completely resected, nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, whose initial treatment may be surgery alone.[24]

Evidence (surgery alone for localized nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma):

- Although standard therapy for children with nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is chemotherapy plus LD-ISRT, there are reports in which patients have been treated with chemotherapy alone or with complete resection of isolated nodal disease without chemotherapy. Surgical resection of localized disease produces a prolonged disease-free survival in a substantial proportion of patients obviating the need for immediate cytotoxic therapy.[24,25,27,28]

- Results from a single-arm Children's Oncology Group (COG) trial provide data to support the strategy of observation after surgical resection and treatment with limited chemotherapy for children with favorable stage IA or IIA Hodgkin lymphoma.[24][Level of evidence: 1iiDi]

- Among 178 patients treated with surgical resection alone for single-node disease (n = 52), chemotherapy alone after complete response (CR) to three cycles of AV-PC (doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy (n = 115), or chemotherapy with low-dose involved-field radiation therapy (LD-IFRT) (21 Gy) after incomplete response to AV-PC chemotherapy (n = 11), the 5-year EFS was 85.5%, and the OS was 100%.

- Five-year EFS was 77% for patients observed after total resection and 88.8% for patients treated with AV-PC chemotherapy.

Advanced-stage nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is very rare, and there is no consensus regarding the optimal treatment, although outcomes for patients are excellent.

Evidence (chemotherapy for nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma with unfavorable characteristics):

- In a retrospective review of 41 cases of advanced-stage nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, many different chemotherapy regimens were used, some included rituximab.[29][Level of evidence: 3iiiA]

- OS was 98%, with the only death resulting from a subsequent neoplasm.

- In a retrospective analysis, 97 intermediate-risk patients with lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma were treated on COG study AHOD0031 (NCT00025259).[30]