NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002-.

PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet].

Show detailsThis PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood and adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Date Last Modified") is the date of the most recent change. The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

General Information About Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH)

Key Points for This Section

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a type of cancer that can damage tissue or cause lesions to form in one or more places in the body.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare cancer that begins in LCH cells. LCH cells are a type of dendritic cell which fights infection. Sometimes there are mutations (changes) in LCH cells as they form. These include mutations of the BRAF, MAP2K1, RAS and ARAF genes. These changes may make the LCH cells grow and multiply quickly. This causes LCH cells to build up in certain parts of the body, where they can damage tissue or form lesions.

LCH is not a disease of the Langerhans cells that normally occur in the skin.

LCH may occur at any age, but is most common in young children. Treatment of LCH in children is different from treatment of LCH in adults. The treatment of LCH in children and the treatment of LCH in adults is described in separate sections of this summary.

Family history of cancer or having a parent who was exposed to certain chemicals may increase the risk of LCH.

Anything that increases your risk of getting a disease is called a risk factor. Having a risk factor does not mean that you will get cancer; not having risk factors doesn't mean that you will not get cancer. Talk with your doctor if you think you may be at risk.

Risk factors for LCH include the following:

- Having a parent who was exposed to certain chemicals.

- Having a parent who was exposed to metal, granite, or wood dust in the workplace.

- A family history of cancer, including LCH.

- Having a personal history or family history of thyroid disease.

- Having infections as a newborn.

- Smoking, especially in young adults.

- Being Hispanic.

- Not being vaccinated as a child.

The signs and symptoms of LCH depend on where it is in the body.

These and other signs and symptoms may be caused by LCH or by other conditions. Check with your doctor if you or your child have any of the following:

Skin and nails

LCH in infants may affect the skin only. In some cases, skin-only LCH may get worse over weeks or months and become a form called high-risk multisystem LCH.

In infants, signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the skin may include:

- Flaking of the scalp that may look like “cradle cap”.

- Flaking in the creases of the body, such as the inner elbow or perineum.

- Raised, brown or purple skin rash anywhere on the body.

In children and adults, signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the skin and nails may include:

Mouth

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the mouth may include:

- Swollen gums.

- Sores on the roof of the mouth, inside the cheeks, or on the tongue or lips.

- Teeth that become uneven or fall out.

Bone

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the bone may include:

- Pain where there is swelling or a lump over a bone.

Children with LCH lesions in bones around the ears or eyes have a high risk for diabetes insipidus and other central nervous system diseases.

Lymph nodes and thymus

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the lymph nodes or thymus may include:

- Swollen lymph nodes.

- Trouble breathing.

- Superior vena cava syndrome. This can cause coughing, trouble breathing, and swelling of the face, neck, and upper arms.

Endocrine system

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the pituitary gland may include:

- Diabetes insipidus. This can cause a strong thirst and frequent urination.

- Slow growth.

- Early or late puberty.

- Being very overweight.

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the thyroid may include:

- Swollen thyroid gland.

- Hypothyroidism. This can cause tiredness, lack of energy, being sensitive to cold, constipation, dry skin, thinning hair, memory problems, trouble concentrating, and depression. In infants, this can also cause a loss of appetite and choking on food. In children and adolescents, this can also cause behavior problems, weight gain, slow growth, and late puberty.

- Trouble breathing.

Eye

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the eye may include:

- Vision problems.

Central nervous system (CNS)

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the CNS (brain and spinal cord) may include:

- Loss of balance, uncoordinated body movements, and trouble walking.

- Trouble speaking.

- Trouble seeing.

- Headaches.

- Changes in behavior or personality.

- Memory problems.

These signs and symptoms may be caused by lesions in the CNS or by CNS neurodegenerative syndrome.

Liver and spleen

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the liver or spleen may include:

- Swelling in the abdomen caused by a buildup of extra fluid.

- Trouble breathing.

- Yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes.

- Itching.

- Easy bruising or bleeding.

- Feeling very tired.

Lung

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the lung may include:

- Collapsed lung. This condition can cause chest pain or tightness, trouble breathing, feeling tired, and a bluish color to the skin.

- Trouble breathing, especially in adults who smoke.

- Dry cough.

- Chest pain.

Bone marrow

Signs or symptoms of LCH that affects the bone marrow may include:

- Easy bruising or bleeding.

- Frequent infections.

Tests that examine the organs and body systems where LCH may occur are used to diagnose LCH.

The following tests and procedures may be used to detect (find) and diagnose LCH or conditions caused by LCH:

- Physical exam and health history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient's health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- Neurological exam: A series of questions and tests to check the brain, spinal cord, and nerve function. The exam checks a person's mental status, coordination, and ability to walk normally, and how well the muscles, senses, and reflexes work. This may also be called a neuro exam or a neurologic exam.

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential: A procedure in which a sample of blood is drawn and checked for the following:

- -

The amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells.

- -

The portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells.

- -

The number and type of white blood cells.

- -

The number of red blood cells and platelets.

- Blood chemistry studies: A procedure in which a blood sample is checked to measure the amounts of certain substances released into the body by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual (higher or lower than normal) amount of a substance can be a sign of disease.

- Liver function test: A blood test to measure the blood levels of certain substances released by the liver. A high or low level of these substances can be a sign of disease in the liver.

- BRAF gene testing: A laboratory test in which a sample of blood or tissue is tested for certain changes in the BRAF gene.

- Urinalysis: A test to check the color of urine and its contents, such as sugar, protein, red blood cells, and white blood cells.

- Water deprivation test: A test to check how much urine is made and whether it becomes concentrated when little or no water is given. This test is used to diagnose diabetes insipidus, which may be caused by LCH.

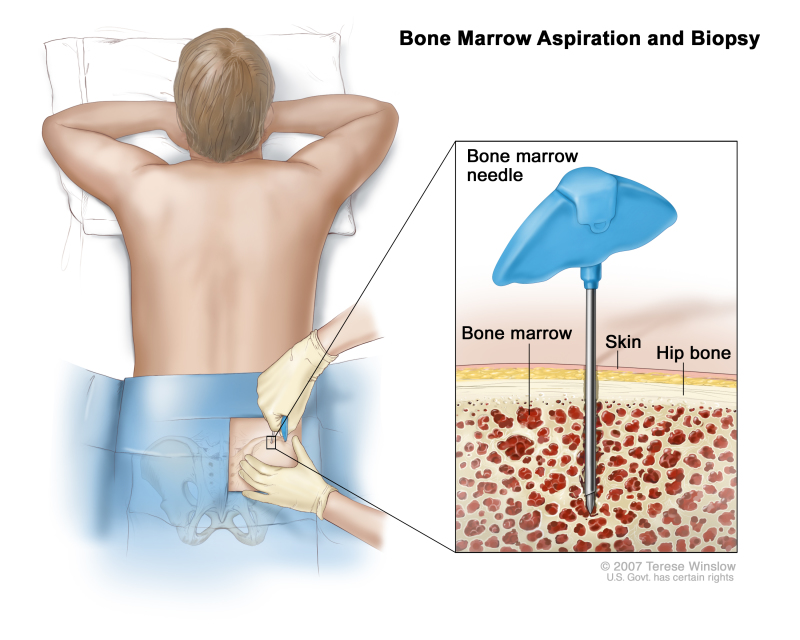

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy: The removal of bone marrow and a small piece of bone by inserting a hollow needle into the hipbone. A pathologist views the bone marrow and bone under a microscope to look for signs of LCH.The following tests may be done on the tissue that was removed:

- Immunohistochemistry: A laboratory test that uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient’s tissue. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to a specific antigen in the tissue sample, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test is used to help diagnose cancer and to help tell one type of cancer from another type of cancer.

- Flow cytometry: A laboratory test that measures the number of cells in a sample, the percentage of live cells in a sample, and certain characteristics of the cells, such as size, shape, and the presence of tumor (or other) markers on the cell surface. The cells from a sample of a patient’s blood, bone marrow, or other tissue are stained with a fluorescent dye, placed in a fluid, and then passed one at a time through a beam of light. The test results are based on how the cells that were stained with the fluorescent dye react to the beam of light.

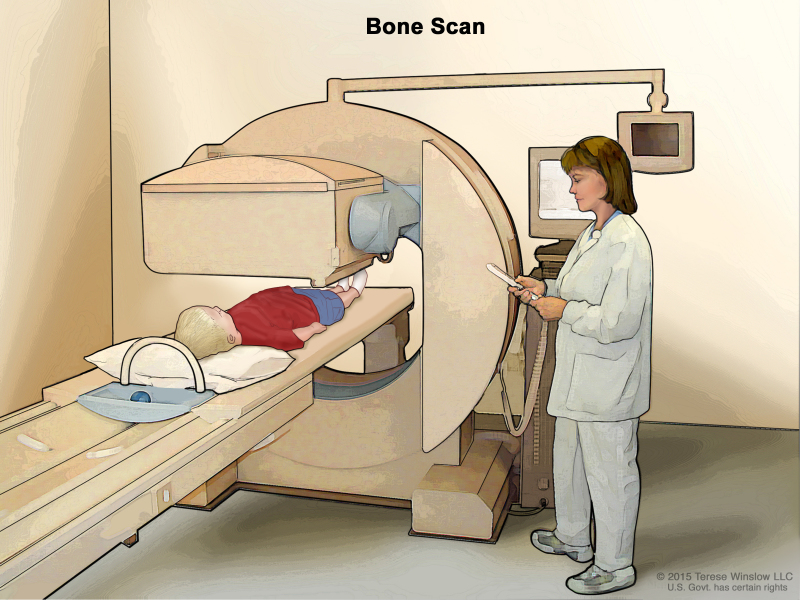

- Bone scan: A procedure to check if there are rapidly dividing cells in the bone. A very small amount of radioactive material is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radioactive material collects in the bones with cancer and is detected by a scanner.

Bone scan. A small amount of radioactive material is injected into the child's vein and travels through the blood. The radioactive material collects in the bones. As the child lies on a table that slides under the scanner, the radioactive material is detected and images are made on a computer screen.

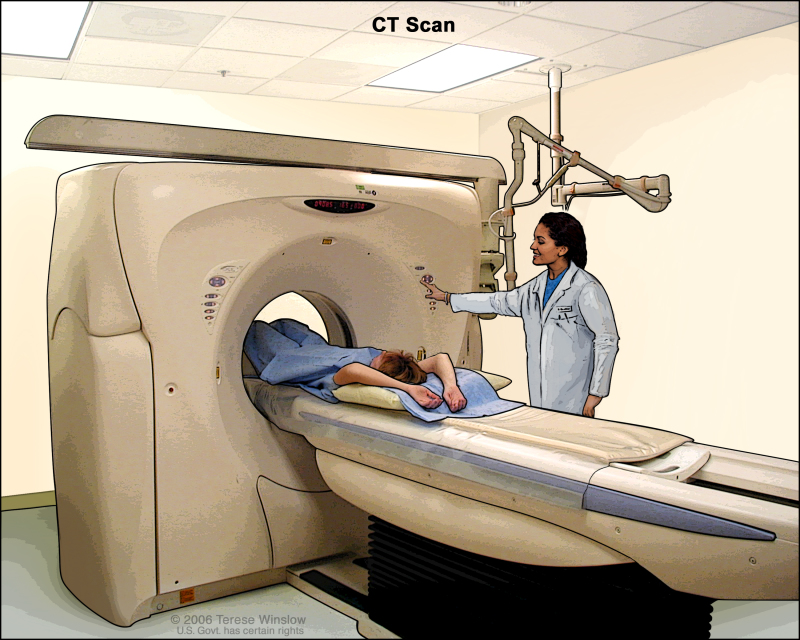

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

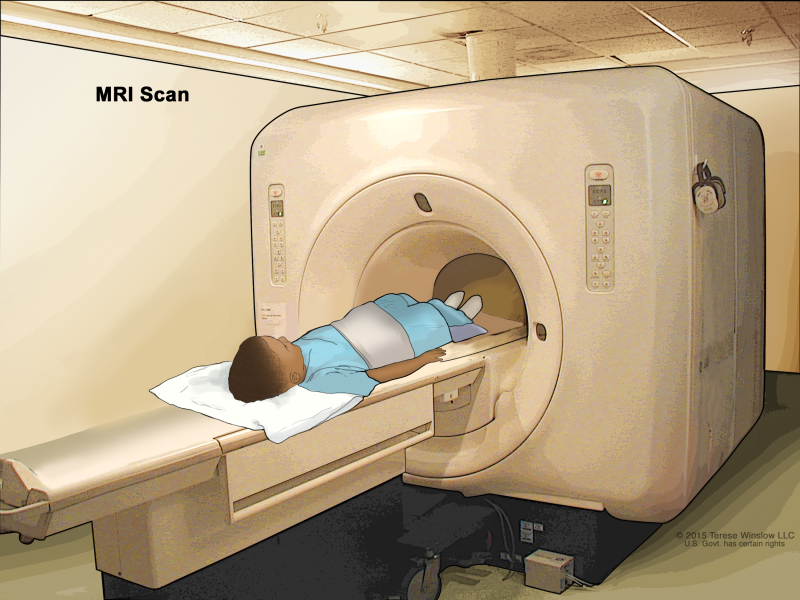

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. A substance called gadolinium may be injected into a vein. The gadolinium collects around the LCH cells so that they show up brighter in the picture. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

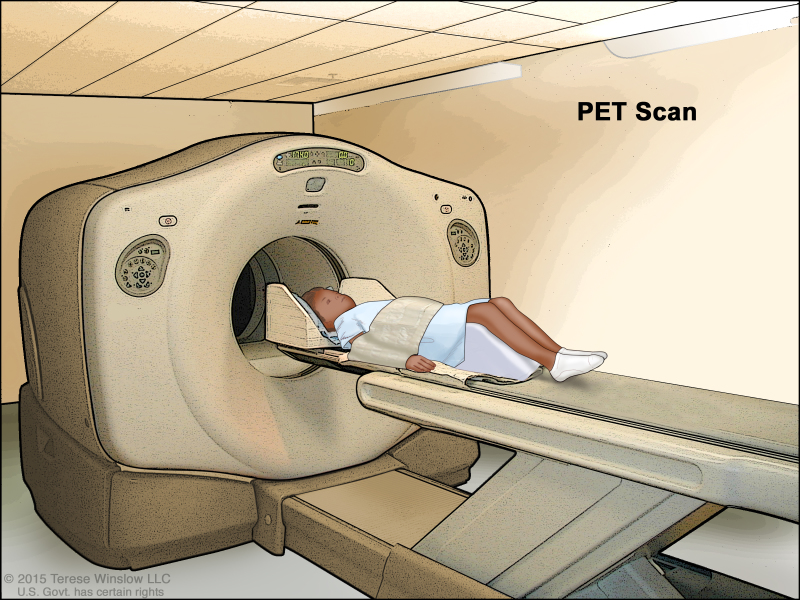

- PET scan (positron emission tomography scan): A procedure to find tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Tumor cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells do.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the PET scanner. The head rest and white strap help the child lie still. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into the child's vein, and a scanner makes a picture of where the glucose is being used in the body. Cancer cells show up brighter in the picture because they take up more glucose than normal cells do.

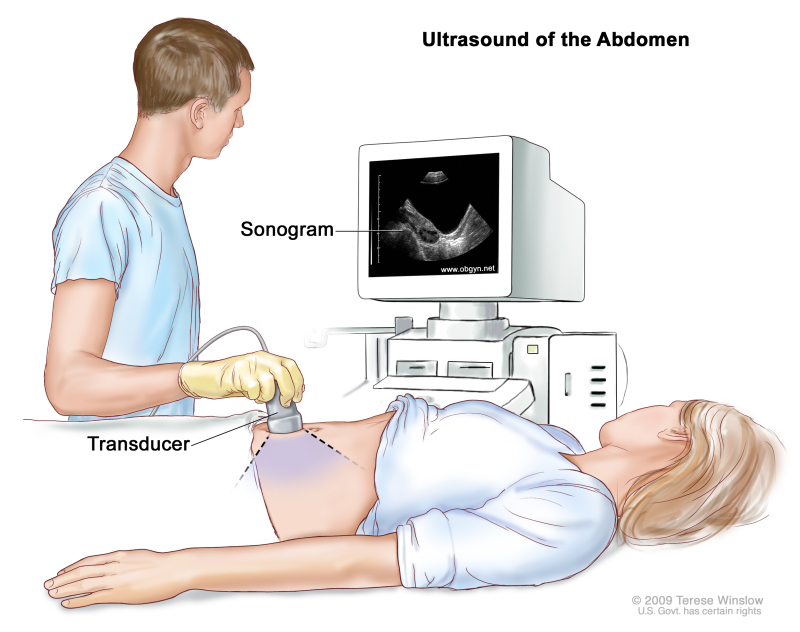

- Ultrasound exam: A procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. The picture can be printed to be looked at later.

- Pulmonary function test (PFT): A test to see how well the lungs are working. It measures how much air the lungs can hold and how quickly air moves into and out of the lungs. It also measures how much oxygen is used and how much carbon dioxide is given off during breathing. This is also called lung function test.

- Bronchoscopy: A procedure to look inside the trachea and large airways in the lung for abnormal areas. A bronchoscope is inserted through the nose or mouth into the trachea and lungs. A bronchoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

- Endoscopy: A procedure to look at organs and tissues inside the body to check for abnormal areas in the gastrointestinal tract or lungs. An endoscope is inserted through an incision (cut) in the skin or opening in the body, such as the mouth. An endoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue or lymph node samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of disease.

- Biopsy: The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for LCH cells. To diagnose LCH, a biopsy of bone, skin, lymph nodes, liver, or other sites of disease may be done.

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

LCH in organs such as the skin, bones, lymph nodes, or pituitary gland usually gets better with treatment and is called "low-risk". LCH in the spleen, liver, or bone marrow is harder to treat and is called "high-risk".

The prognosis and treatment options depend on the following:

- How old the patient is when diagnosed with LCH.

- Which organs or body systems are affected by LCH.

- How many organs or body systems the cancer affects.

- Whether the cancer is found in the liver, spleen, bone marrow, or certain bones in the skull.

- How quickly the cancer responds to initial treatment.

- Whether there are certain changes in the BRAF gene.

- Whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has come back (recurred).

In infants up to one year of age, LCH may go away without treatment.

Stages of LCH

Key Points for This Section

There is no staging system for Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

The extent or spread of cancer is usually described as stages. There is no staging system for LCH.

Treatment of LCH is based on where LCH cells are found in the body and whether the LCH is low risk or high risk.

LCH is described as single-system disease or multisystem disease, depending on how many body systems are affected:

- Single-system LCH: LCH is found in one part of an organ or body system or in more than one part of that organ or body system. Bone is the most common single place for LCH to be found.

- Multisystem LCH: LCH occurs in two or more organs or body systems or may be spread throughout the body. Multisystem LCH is less common than single-system LCH.

LCH may affect low-risk organs or high-risk organs:

- Low-risk organs include the skin, bone, lungs, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, pituitary gland, thyroid gland, thymus, and central nervous system (CNS).

Recurrent LCH

Recurrent LCH is cancer that has recurred (come back) after it has been treated. The cancer may come back in the same place or in other parts of the body. It often recurs in the bone, ears, skin, or pituitary gland. LCH often recurs the year after stopping treatment. When LCH recurs, it may also be called reactivation.

Treatment Option Overview for LCH

Key Points for This Section

There are different types of treatment for patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

Different types of treatments are available for patients with LCH. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment. Whenever possible, patients should take part in a clinical trial in order to receive new types of treatment for LCH. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials are taking place in many parts of the country. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website. Choosing the most appropriate treatment is a decision that ideally involves the patient, family, and health care team.

Children with LCH should have their treatment planned by a team of health care providers who are experts in treating childhood cancer.

Treatment will be overseen by a pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer. The pediatric oncologist works with other pediatric healthcare providers who are experts in treating children with LCH and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. These may include the following specialists:

Nine types of standard treatment are used:

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy). When chemotherapy is placed directly onto the skin or into the cerebrospinal fluid, an organ, or a body cavity such as the abdomen, the drugs mainly affect cancer cells in those areas (regional chemotherapy).

Chemotherapy may be given by injection or by mouth or applied to the skin to treat LCH.

Surgery

Surgery may be used to remove LCH lesions and a small amount of nearby healthy tissue. Curettage is a type of surgery that uses a curette (a sharp, spoon-shaped tool) to scrape LCH cells from bone.

When there is severe liver or lung damage, the entire organ may be removed and replaced with a healthy liver or lung from a donor.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. Ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation therapy may be given using a special lamp that directs radiation toward LCH skin lesions.

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a cancer treatment that uses a drug and a certain type of laser light to kill cancer cells. A drug that is not active until it is exposed to light is injected into a vein. The drug collects more in cancer cells than in normal cells. For LCH, laser light is aimed at the skin and the drug becomes active and kills the cancer cells. Photodynamic therapy causes little damage to healthy tissue. Patients who have photodynamic therapy should not spend too much time in the sun.

In one type of photodynamic therapy, called psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy, the patient receives a drug called psoralen and then ultraviolet A radiation is directed to the skin.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defenses against cancer. This type of cancer treatment is also called biotherapy or biologic therapy. There are different types of immunotherapy:

- Interferon is used to treat LCH of the skin.

- Thalidomide is used to treat LCH.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is used to treat CNS neurodegenerative syndrome.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of treatment that uses drugs or other substances to attack cancer cells. Targeted therapies may cause less harm to normal cells than chemotherapy or radiation therapy do. There are different types of targeted therapy:

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors block signals needed for tumors to grow. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors used to treat LCH include the following:

- Imatinib mesylate stops blood stem cells from turning into dendritic cells that may become cancer cells.

- BRAF inhibitors block proteins needed for cell growth and may kill cancer cells. The BRAF gene is found in a mutated (changed) form in some LCH and blocking it may help keep cancer cells from growing.

- Vemurafenib and dabrafenib are BRAF inhibitors used to treat LCH.

Other drug therapy

Other drugs used to treat LCH include the following:

- Steroid therapy, such as prednisone, is used to treat LCH lesions.

- Bisphosphonate therapy (such as pamidronate, zoledronate, or alendronate) is used to treat LCH lesions of the bone and to lessen bone pain.

- Anti-inflammatory drugs are drugs (such as pioglitazone and rofecoxib) that are commonly used to decrease fever, swelling, pain, and redness. Anti-inflammatory drugs and chemotherapy may be given together to treat adults with bone LCH.

- Retinoids, such as isotretinoin, are drugs related to vitamin A that can slow the growth of LCH cells in the skin. The retinoids are taken by mouth.

Stem cell transplant

Stem cell transplant is a method of giving chemotherapy and replacing blood-forming cells destroyed by the LCH treatment. Stem cells (immature blood cells) are removed from the blood or bone marrow of the patient or a donor and are frozen and stored. After the chemotherapy is completed, the stored stem cells are thawed and given back to the patient through an infusion. These reinfused stem cells grow into (and restore) the body's blood cells.

Observation

Observation is closely monitoring a patient's condition without giving any treatment until signs or symptoms appear or change.

New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

Information about clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Treatment for Langerhans cell histiocytosis may cause side effects.

For information about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, see our Side Effects page.

Side effects from cancer treatment that begin after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include the following:

- Slow growth and development.

- Hearing loss.

- Bone, tooth, liver, and lung problems.

- Changes in mood, feeling, learning, thinking, or memory.

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the effects cancer treatment can have on your child. (See the PDQ summary on Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer for more information.)

Many patients with multisystem LCH have late effects caused by treatment or by the disease itself. These patients often have long-term health problems that affect their quality of life.

Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today's standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their treatment.

Some clinical trials only include patients who have not yet received treatment. Other trials test treatments for patients whose cancer has not gotten better. There are also clinical trials that test new ways to stop cancer from recurring (coming back) or reduce the side effects of cancer treatment.

Clinical trials are taking place in many parts of the country. Information about clinical trials supported by NCI can be found on NCI’s clinical trials search webpage. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

When treatment of LCH stops, new lesions may appear or old lesions may come back.

Many patients with LCH get better with treatment. However, when treatment stops, new lesions may appear or old lesions may come back. This is called reactivation (recurrence) and may occur within one year after stopping treatment. Patients with multisystem disease are more likely to have a reactivation. Common sites of reactivation are bone, ears, or skin. Diabetes insipidus also may develop. Less common sites of reactivation include lymph nodes, bone marrow, spleen, liver, or lung. Some patients may have more than one reactivation over a number of years.

Follow-up tests may be needed.

Because of the risk of reactivation, LCH patients should be monitored for many years. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose LCH may be repeated. This is to see how well the treatment is working and if there are any new lesions. These tests may include:

- MRI.

Other tests that may be needed include:

- Brain stem auditory evoked response (BAER) test: A test that measures the brain's response to clicking sounds or certain tones.

- Pulmonary function test (PFT): A test to see how well the lungs are working. It measures how much air the lungs can hold and how quickly air moves into and out of the lungs. It also measures how much oxygen is used and how much carbon dioxide is given off during breathing. This is also called a lung function test.

- Chest x-ray: An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

The results of these tests can show if your condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back). These tests are sometimes called follow-up tests or check-ups. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Treatment of Low-Risk LCH in Children

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Skin Lesions

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) skin lesions may include:

When severe rashes, pain, ulceration, or bleeding occur, treatment may include the following:

- Chemotherapy given by mouth or vein.

- Chemotherapy applied to the skin.

- Photodynamic therapy with psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy.

Lesions in Bones or Other Low-Risk Organs

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood LCH bone lesions in the front, sides, or back of the skull, or in any other single bone may include:

- Low-dose radiation therapy for lesions that affect nearby organs.

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood LCH lesions in bones around the ears or eyes is done to lower the risk of diabetes insipidus and other long-term problems. Treatment may include:

- Chemotherapy and steroid therapy.

- Surgery (curettage).

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood LCH lesions of the spine or thigh bone may include:

- Low-dose radiation therapy.

- Chemotherapy, for lesions that spread from the spine into nearby tissue.

- Surgery to strengthen the weakened bone by bracing or fusing the bones together.

Treatment of two or more bone lesions may include:

- Chemotherapy and steroid therapy.

Treatment of two or more bone lesions combined with skin lesions, lymph node lesions, or diabetes insipidus may include:

- Chemotherapy with or without steroid therapy.

CNS Lesions

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood LCH central nervous system (CNS) lesions may include:

- Chemotherapy with or without steroid therapy.

Treatment of newly diagnosed LCH CNS neurodegenerative syndrome may include:

- Chemotherapy.

- Immunotherapy (IVIG) with or without chemotherapy.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

Treatment of High-Risk LCH in Children

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood LCH multisystem disease lesions in the spleen, liver, or bone marrow and another organ or site may include:

- Chemotherapy and steroid therapy. Higher doses of more than one chemotherapy drug and steroid therapy may be given to patients whose tumors do not respond to initial chemotherapy.

- A liver transplant for patients with severe liver damage.

- A clinical trial that tailors the patient's treatment based on features of the cancer and how it responds to treatment.

- A clinical trial of chemotherapy and steroid therapy.

Treatment of Recurrent, Refractory, and Progressive Childhood LCH in Children

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Recurrent LCH is cancer that cannot be detected for some time after treatment and then comes back. Refractory LCH is cancer that does not get better with treatment. Progressive LCH is cancer that continues to grow during treatment.

Treatment of recurrent, refractory, or progressive low-risk LCH may include:

- Chemotherapy with or without steroid therapy.

Treatment of recurrent, refractory, or progressive high-risk multisystem LCH may include:

Treatments being studied for recurrent, refractory, or progressive childhood LCH include the following:

- A clinical trial that tailors the patient's treatment based on features of the cancer and how it responds to treatment.

Treatment of LCH in Adults

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) in adults is a lot like LCH in children and can form in the same organs and systems as it does in children. These include the endocrine and central nervous systems, liver, spleen, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract. In adults, LCH is most commonly found in the lung as single-system disease. LCH in the lung occurs more often in young adults who smoke. Adult LCH is also commonly found in bone or skin.As in children, the signs and symptoms of LCH depend on where it is found in the body. See the General Information section for the signs and symptoms of LCH.

Tests that examine the organs and body systems where LCH may occur are used to detect (find) and diagnose LCH. See the General Information section for tests and procedures used to diagnose LCH.

In adults, there is not a lot of information about what treatment works best. Sometimes, information comes only from reports of the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of one adult or a small group of adults who were given the same type of treatment.

Treatment of LCH of the Lung in Adults

Treatment for LCH of the lung in adults may include:

- Quitting smoking for all patients who smoke. Lung damage will get worse over time in patients who do not quit smoking. In patients who quit smoking, lung damage may get better or it may get worse over time.

- Lung transplant for patients with severe lung damage.

Sometimes LCH of the lung will go away or not get worse even if it's not treated.

Treatment of LCH of the Bone in Adults

Treatment for LCH that affects only the bone in adults may include:

- Surgery with or without steroid therapy.

- Chemotherapy with or without low-dose radiation therapy.

- Bisphosphonate therapy, for severe bone pain.

- Anti-inflammatory drugs with chemotherapy.

Treatment of LCH of the Skin in Adults

Treatment for LCH that affects only the skin in adults may include:

- Photodynamic therapy with psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) radiation.

- Chemotherapy or immunotherapy given by mouth, such as methotrexate, thalidomide, hydroxyurea, or interferon.

Treatment for LCH that affects the skin and other body systems in adults may include:

- Chemotherapy.

Treatment of Single-System and Multisystem LCH in Adults

Treatment of single-system and multisystem disease in adults that does not affect the lung, bone, or skin may include:

For more information about LCH trials for adults, see the Histiocyte Society website.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

To Learn More About Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

For more information from the National Cancer Institute about Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment, see the following:

For more childhood cancer information and other general cancer resources, see the following:

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government’s center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood and adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/langerhans/patient/langerhans-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389196]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s E-mail Us.

- General Information About Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH)

- Stages of LCH

- Treatment Option Overview for LCH

- Treatment of Low-Risk LCH in Children

- Treatment of High-Risk LCH in Children

- Treatment of Recurrent, Refractory, and Progressive Childhood LCH in Children

- Treatment of LCH in Adults

- To Learn More About Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

- About This PDQ Summary

- Review Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Review Childhood Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Review Childhood Chordoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Chordoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Review Childhood Testicular Cancer (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Testicular Cancer (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Review Childhood Mesothelioma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Mesothelioma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Treatment (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information Summarie...Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Treatment (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information Summaries

- LOC124625859 [Homo sapiens]LOC124625859 [Homo sapiens]Gene ID:124625859Gene

- Collagen Type XIICollagen Type XIIA fibril-associated collagen found in many tissues bearing high tensile stress, such as TENDONS and LIGAMENTS. It is comprised of a trimer of three identical alpha1(XII) chain...<br/>Year introduced: 2002MeSH

- Zyg11b zyg-11 family member B, cell cycle regulator [Rattus norvegicus]Zyg11b zyg-11 family member B, cell cycle regulator [Rattus norvegicus]Gene ID:362559Gene

- Ubtd2 ubiquitin domain containing 2 [Mus musculus]Ubtd2 ubiquitin domain containing 2 [Mus musculus]Gene ID:327900Gene

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...