NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Totten A, Womack DM, McDonagh MS, et al. Improving Rural Health Through Telehealth-Guided Provider-to-Provider Communication [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2022 Dec. (Comparative Effectiveness Review, No. 254.)

Improving Rural Health Through Telehealth-Guided Provider-to-Provider Communication [Internet].

Show detailsResults of Literature Searches

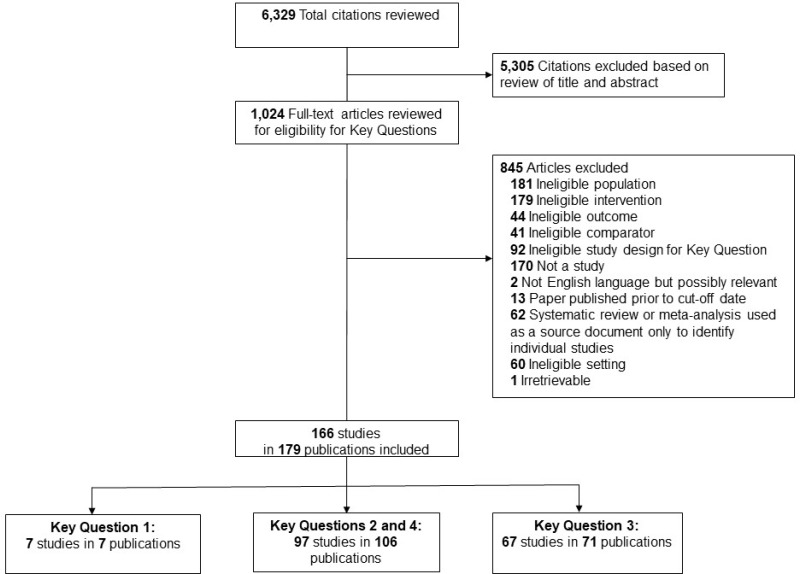

A total of 6,329 references were identified from electronic database searches. After dual review of abstracts, 1,024 articles were evaluated for inclusion. Search results and selection of studies are summarized in the literature flow diagram above (Figure B-1). A total of 166 studies (in 179 publications) were included for at least one key question.6–184 Seven studies were included for Key Question 1, 97 studies in 106 publications were included for Key Question 2, and 67 studies in 71 publications were included for Key Question 3. A list of included studies appears in Appendix C and excluded studies with reason for exclusion in Appendix G.

Description of Included Studies

Key Question 1

The systematic review protocol and a request for unpublished information was posted by AHRQ on the Federal Register Supplemental Evidence and Data (SEADs) webpage. Additionally, we sent emails requesting information to individual federal agencies as well as non governmental organizations involved in telehealth and experts familiar with telehealth practices and policy. Specific program offices contacted included FedTel, the U.S. Federal government working group on Teleheath, the Telehealth Focused Rural Health Research Center Program of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the COVID-19 Telehealth Impact Study organized by the COVID-19 Healthcare Coalition Telehealth Impact Study Work Group with leadership from Mayo Clinic and the MITRE Corporation.

We also explored the possibility of identifying trends through claims data. Although the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has approved Common Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes 99446–99449, 99451 and 99452 for interprofessional electronic assessment and management and referral services provided by a consultative physician, or other qualified health care professional (QHP) and by a patient’s treating/requesting physician/QHP (in the case of 99452), there is anecdotal evidence that use of these billing codes is very low (personal communications).185 It is very likely that informal interprofessional consultations are occurring in a non-compensated manner, but such interactions would not be included in billing records, and literature describing the frequency of informal interprofessional consultations is not currently available.

We did not receive any additional unpublished evidence on provider-to-provider telehealth in the rural U.S. usable for this report. While use of telehealth for patient and provider interactions has been documented, particularly the increase as part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic,186, 187 trends in provider-to-provider telehealth have not yet been documented to the same extent. Details can be found in Appendix Table D-1.

Table B-1Characteristics of included studies for Key Question 1

Key Questions 2 and 4

Study details can be found in Appendix Tables D-2, D-3, D-4, D-5, D-6, D-7, D-8, D-9, E-1, E-2, E-3, and E-4.

Table B-2Characteristics of included studies for Key Question 2

| Characteristic | Categories | Number of Articles - 106 | Percentage of Articles | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic Location | United States | 63 | 59% | 10, 11, 18, 21, 23, 29, 36, 38–41, 44–49, 51, 55, 58–60, 66, 72, 75, 78, 84, 92, 93, 96, 98, 100, 101, 103–107, 110, 114, 117, 120, 130–132, 139, 142, 143, 150, 153, 154, 158, 159, 164, 167, 173, 175, 176, 178, 182, 184,35, 172 |

| Australia | 15 | 14% | 13, 19, 20, 27, 34, 42, 52, 70, 97, 99, 111, 122, 128, 136, 156 | |

| Canada | 5 | 5% | 65, 82, 85, 145, 148, 155 | |

| United Kingdom | 3 | 3% | 81, 152, 165 | |

| Korea | 3 | 3% | 31, 76, 79 | |

| Italy | 2 | 2% | 25, 26 | |

| Countries with a single study* | 14 | 13% | 12, 16, 22, 37, 53, 61, 81, 86, 112, 124, 138, 141, 151, 179 | |

| Study Design | RCT | 23 | 22% | 19, 22, 29, 31, 35, 36, 38, 45, 47–49, 53, 61, 82, 86, 110, 131, 132, 155, 172, 179, 184 |

| Observational- before/after | 25 | 24% | 13, 16, 20, 27, 41, 42, 44, 52, 55, 75, 78, 87, 105, 111, 112, 114, 120, 122, 128, 143, 150, 152, 154, 159, 178 | |

| Observational- pre/post | 18 | 17% | 10, 18, 23, 66, 79, 84, 85, 96, 98, 99, 107, 117, 130, 136, 145, 148, 167, 175 | |

| Observational- prospective cohort | 21 | 20% | 11, 12, 25, 26, 34, 37, 59, 60, 65, 70, 76, 93, 100, 103, 106, 124, 138, 141, 142, 153, 176 | |

| Observational- retrospective cohort | 19 | 18% | 21, 39, 40, 51, 58, 72, 81, 92, 97, 101, 104, 139, 151, 156, 158, 164, 165, 173, 182 | |

| Risk of Bias | Low | 5 | 5% | 38, 82, 120, 132, 148 |

| Medium | 75 | 71% | 10–12, 16, 19–21, 25–27, 29, 31, 34–37, 39–41, 44–49, 51, 53, 58–61, 65, 70, 72, 76, 85, 86, 92, 93, 100, 101, 103–105, 110–112, 114, 117, 122, 124, 128, 131, 138, 139, 141–143, 145, 150, 151, 153–156, 158, 159, 164, 172, 173, 175, 176, 179, 182, 184 | |

| High | 26 | 25% | 13, 18, 22, 23, 42, 52, 55, 66, 75, 78, 79, 81, 84, 87, 96–99, 106, 107, 130, 136, 152, 165, 167, 178 | |

| Sample Size | Under 100 | 30 | 28% | 18, 19, 22, 23, 25, 31, 37, 52, 66, 70, 81, 84, 86, 96–99, 111, 112, 117, 136, 139, 142, 145, 152, 155, 165, 167, 176, 184 |

| 100–500 | 48 | 45% | 11, 12, 16, 20, 26, 29, 35, 36, 38–40, 42, 44–49, 58, 59, 61, 65, 72, 76, 78, 79, 82, 85, 92, 93, 101, 110, 120, 124, 130–132, 138, 143, 148, 151, 154, 156, 159, 164, 172, 173, 178 | |

| 501–1000 | 6 | 6% | 10, 53, 75, 103, 122, 153 | |

| 1001–10,000 | 11 | 10% | 21, 27, 34, 51, 100, 104–107, 141, 179 | |

| 10,000+ | 7 | 7% | 41, 53, 55, 87, 114, 150, 158 | |

| Not reported/unclear | 2 | 2% | 13, 175, 182 | |

| Mode of Telehealth | Video | 79 | 75% | 11, 13, 16, 18, 20–23, 27, 31, 34–36, 38–42, 44, 47, 51, 52, 55, 58–61, 65, 66, 70, 72, 75, 76, 78, 79, 81, 84–87, 92, 93, 96–101, 103–107, 111, 114, 120, 122, 124, 128, 132, 139, 141–143, 148, 150, 153, 155, 156, 158, 159, 165, 167, 175, 176, 178, 182, 184 |

| Data store and forward | 4 | 4% | 37, 82, 172, 179 | |

| Electronic chart/record review | 3 | 3% | 29, 45, 152 | |

| Mixed modalities | 10 | 12% | 19, 46, 48, 49, 110, 112, 131, 138, 145, 154 | |

| Data streaming | 1 | 1% | 25 | |

| Telephone | 2 | 2% | 10, 25 | |

| Whats App | 1 | 1% | 12 | |

| SMS Based | 1 | 1% | 53 | |

| Online Module | 3 | 3% | 117, 130, 136 | |

| NR/Unclear | 2 | 2% | 164, 173 | |

| Clinical category | Inpatient | 18 | 17% | 13, 21, 27, 41, 52, 55, 59, 60, 72, 75, 78, 92, 93, 111, 122, 128, 154, 178 |

| Outpatient | 37 | 35% | 10, 22, 29, 31, 34–37, 45–49, 70, 76, 79, 81, 82, 86, 87, 97, 98, 110, 120, 131, 132, 138, 139, 145, 151, 152, 155, 156, 165, 172, 176, 179 | |

| EMS/ED | 28 | 26% | 12, 20, 25, 26, 38–40, 44, 58, 61, 65, 100, 101, 103–106, 111, 112, 114, 124, 141, 150, 153, 159, 164, 173, 182 | |

| Education/mentoring | 23 | 22% | 11, 19, 23, 42, 51, 53, 66, 84, 85, 96, 99, 107, 117, 128, 130, 136, 142, 143, 148, 158, 167, 175, 184 | |

| Outcome categories | Patient | 71 | 67% | 10–13, 16, 20–22, 25–27, 29, 31, 34, 36–38, 40, 44, 46, 47, 49, 52, 55, 58–61, 65, 70, 72, 75, 76, 78, 79, 81, 82, 86, 87, 92, 93, 98, 100, 104–106, 110–112, 114, 122, 124, 128, 139, 141, 143, 145, 151–155, 159, 164, 167, 172, 175, 176, 178, 179, 182 |

| Provider | 32 | 30% | 18, 19, 23, 38–42, 51–53, 58, 66, 78, 84, 85, 96, 99, 101, 103, 107, 117, 130, 136, 142, 143, 148, 150, 158, 165, 175, 184 | |

| Payer | 13 | 12% | 35, 37, 45, 70, 97, 120, 131, 132, 152, 156, 173, 182,16 |

- *

China, Denmark, Scotland, Finland, New Zealand, Spain, Germany, Chile, Turkey, Japan, Sweden, Taiwan, Vietnam

Key Question 3

Additional study details can be found in Appendix Table D-10.

Table B-3Characteristics of included studies for Key Question 3

| Characteristic | Categories | Number of Articles (71 total) | Percentage of Articles | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic Location | United States | 35 | 49% | 6, 7, 9, 17, 24, 30, 33, 56, 57, 63, 64, 67, 73, 77, 80, 90, 91, 108, 115, 126, 127, 129, 134, 135, 144, 146, 147, 150, 157, 166, 169, 170, 174, 180, 183, 185 |

| Sweden | 1 | 1% | 71 | |

| Norway | 2 | 3% | 160, 161 | |

| Germany | 2 | 3% | 95, 119 | |

| Australia | 18 | 25% | 14, 15, 28, 43, 69, 74, 83, 89, 102, 113, 116, 121, 123, 125, 140, 162, 163, 168 | |

| Canada | 5 | 7% | 32, 54, 62, 68, 177 | |

| New Zealand | 1 | 1% | 88 | |

| Scotland | 3 | 4% | 16, 94, 171 | |

| South Africa | 1 | 1% | 118 | |

| Multiple | 2 | 2% | 133, 137 | |

| Countries with a single study* | 1 | 7% | 109 | |

| Method | Program statistics | 1 | 1% | 91 |

| Program records | 6 | 8% | 54, 63, 74, 126, 162, 163 | |

| Program review | 3 | 4% | 113, 116, 123 | |

| Program reporting | 1 | 1% | 125 | |

| Program manager observations | 1 | 1% | 9 | |

| Patient records | 3 | 4% | 54, 68, 140 | |

| Registries | 3 | 4% | 6, 7, 146 | |

| Hospital records | 1 | 1% | 150 | |

| Administrative data | 4 | 6% | 6, 7, 146, 174 | |

| Financial data | 1 | 1% | 90 | |

| EHR data | 1 | 1% | 125 | |

| EMR data | 1 | 1% | 166 | |

| Pre-questionnaire | 1 | 1% | 9 | |

| Survey | 20 | 28% | 17, 30, 32, 43, 56, 73, 80, 91, 108, 109, 115, 118, 125, 127, 134, 135, 137, 150, 174, 180 | |

| Pilot tests | 1 | 1% | 64 | |

| Comparison of two models | 2 | 3% | 169, 170 | |

| Interview/Focus groups | 28 | 39% | 14–16, 24, 28, 67, 69, 71, 73, 80, 83, 88–90, 94, 95, 102, 119, 121, 129, 135, 144, 160–163, 166, 168, 171, 177, 183 | |

| Exit interviews focused on case presentation | 1 | 1% | 9 | |

| Chart review | 5 | 7% | 32, 62, 91, 162, 163 | |

| Case study | 4 | 6% | 14, 28, 33, 147 | |

| Case reports | 2 | 3% | 14, 28 | |

| Case review | 3 | 4% | 24, 115, 157 | |

| Site visits | 4 | 6% | 57, 90, 135, 166 | |

| Patient and staff evaluations | 1 | 1% | 32 | |

| Review of state statutes and regulations | 1 | 1% | 77 | |

| Document analysis | 2 | 3% | 133, 135 | |

| Clinical category | Inpatient | 8 | 11% | 16, 118, 133 |

| Outpatient | 30 | 42% | 24, 32, 43, 54, 62–64, 69, 71, 74, 80, 91, 102, 113, 116, 119, 125, 126, 135, 140, 162, 163, 168, 171 | |

| Telestroke and Emergency Care | 20 | 28% | 6, 7, 14, 28, 33, 77, 88, 90, 94, 134, 146, 147, 150, 160, 161, 166, 169, 170, 180 | |

| Education/mentoring | 13 | 18% | 9, 56, 68, 73, 115, 121, 127, 144, 157, 174, 183 | |

| Outcome categories | Facilitators | 55 | 77% | 6, 7, 9, 16, 24, 32, 33, 43, 54, 56, 62–64, 68, 69, 71, 73, 74, 77, 80, 88, 90, 91, 94, 102, 113, 115, 116, 118, 119, 121, 125–127, 133–135, 140, 144, 146, 147, 150, 157, 160–163, 166, 168–171, 174, 180, 183 |

| Barriers | 51 | 72% | 6, 7, 9, 16, 24, 32, 33, 54, 56, 62–64, 68, 69, 71, 73, 74, 77, 80, 88, 90, 91, 94, 102, 113, 115, 116, 118, 119, 121, 125–127, 133–135, 140, 144, 146, 147, 150, 157, 162, 163, 166, 168, 170, 171, 174, 180, 183 |

Table B-4 repeats the number of times a construct was mentioned and adds the number of publications and the number of settings out of the four possible settings (inpatient, outpatient, EMS/ED, or Education/Mentoring) in which these studies were conducted. This examination demonstrates that the constructs are relevant in all or most of the settings.

We also summarized facilitators and barriers by health care setting (inpatient, outpatient, emergency, and education/mentoring) in two ways. First, Table B-5 reports the number of barriers and facilitators by setting. Included studies of provider-to-provider telehealth for EMS/ED and education/mentoring reported more faciliators the barriers. This was reversed infor inpatient studies and the number of reports were about equal for outpatient care. Next, we created tables by setting and clinical indication similar to how the results are organized for Key Question 2. These tables provide the number of studies we identified for each clinical indication with a brief description of the telehealth interventions; basic information about the studies for each topic, including the method, size and location; implementation facilitators and barriers identified in the study as well as the impact cited as an indicator of successful implementation or motivation for sustainment. Not all studies sought to identify all three so the number of facilitators, barriers, and indicators of impact varies by topic. Finally, the studies we identified that compared strategies or interventions we described these in the narrative text for each setting.

Table B-4Distribution of CFIR constructs

| Barrier or Facilitator | CFIR Contructs | # Settinqs | # Mentions | # Publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Leadership Engagement | 4 | 13 | 10 |

| Implementation Climate | 4 | 13 | 11 | |

| Patient Needs & Resources | 4 | 32 | 25 | |

| Planning | 4 | 11 | 9 | |

| Compatibility | 4 | 33 | 23 | |

| External Policy & Incentives | 4 | 18 | 12 | |

| Adaptability | 4 | 9 | 9 | |

| Knowledge & Beliefs about the Intervention | 4 | 16 | 11 | |

| Available Resources | 4 | 60 | 40 | |

| Reflecting & Evaluating | 4 | 12 | 11 | |

| Access to Knowledge & Information | 4 | 57 | 36 | |

| Networks & Communications | 4 | 37 | 30 | |

| Engaging | 4 | 23 | 18 | |

| Barriers | Cost | 3 | 15 | 13 |

| Readiness for Implementation | 3 | 17 | 12 | |

| Formally Appointed Internal Implementation Leaders | 3 | 7 | 7 | |

| Executing | 3 | 19 | 12 | |

| Relative Priority | 3 | 8 | 8 | |

| Complexity | 2 | 11 | 8 |

Table B-5Facilitators and barriers by topic area

| Topic | Facilitator or Barrier | # Mentions | # Publications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient | Barrier | 45 | 9 |

| Facilitator | 24 | 8 | |

| Outpatient | Barrier | 95 | 26 |

| Facilitator | 90 | 25 | |

| ED/EMS | Barrier | 28 | 7 |

| Facilitator | 65 | 19 | |

| Education/Mentoring | Barrier | 24 | 7 |

| Facilitator | 40 | 13 |

Inpatient

We identified eight assessments of implementation of provider-to-provider telehealth in rural areas that addressed inpatient care including intensive care, use of anesthesia, stroke rehabilitation, teletrauma, multidisciplinary specialty consultation, and telerobotics (Table B-6, Appendix Table D-10). One study compared facilitators and barriers in ICU programs using centralized monitoring (CM) versus virtual consult (VC) models,133 one study used surveys to evaluate phone support consultation in South Africa,118 and one study used focus groups in Scotland to describe user experiences with video team consultations.16

One study of remote ICUs directly compared the facilitators and barriers for CM, which uses a hub with intensivists and hardwired data transfer and VC that uses portable equipment to connect local providers to relevant specialists This study analyzed documents collected as part of a systematic review of effectiveness of remote ICU programs that use CM or VC.133 The structural differences in the models drove the differences in barriers and facilitators such as lower cost and faster start-up for VC compared to the CM, but VC required more effort to integrate into workflows (Table B-6). Based on surveys of rural physicians who were trained in person and then offered telephone support when they needed to use anesthesia, Ngala et al. identified that an important barrier was remote consultants lacked understanding of the rural environment (Table B-6).118 The study of stroke rehabilitation video team consultations reported that lack of technological issues supported implementation and that the consultation increased the patient representative’s confidence in the care provided locally (Table B-6).16

Table B-6Findings of inpatient implementation studies

|

Topic Number of Studies Intervention |

Method N* Location | Facilitators | Barriers | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Remote ICU 1 CM compared to VC |

Document analysis N=91 documents Varied133 |

|

| Not reported |

|

Anesthesia 1 Phone support following in person training |

Survey N=17 rural physicians South Africa118 |

|

| Not reported |

|

Stroke rehabilitation 1 Specialist participation via video in remote team meeting |

Focus Group N=12 people; different roles in program Scotland16 |

|

|

|

|

Teletrauma 1 |

Interview N=14 stakeholders Canada177 |

|

|

|

|

Robotic Telemedicine 1 |

Survey N=38 health care institutions United States, Canada, Ireland137 | Not reported |

| Not reported |

|

Multidisciplinary Specialty Consultation 3 |

Interview N=63 hospitals Australia15 Secondary analysis national survey data N= 4,608 hospitals U.S. 50 States30 Method= N=8 hospitals U.S. Montana, Nevada, North Dakota57 |

|

| Not reported |

- *

N is used here to represent the unit of analysis, which may be number of individual participants or may be number of health care sites or systems.

Abbreviations: CM = centralized monitoring; ICU = intensive care unit; VC = virtual consult.

Table B-7 provides the barriers and facilitators from studies of provider-to-provider telehealth for inpatient studies standardized by CFIR constructs. While there are fewer studies of inpatient care, the barriers and facilitators are not repeated in multiple studies. The most frequently repeated are complexity cited seven times as a barrier and available resources cited as a facilitator six times.

Table B-7Inpatient: barriers and facilitators by CFIR constructs

| Type | Facilitator or Barrier Name | Facilitator or Barrier Number of Mentions | Reference Number(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barrier | Access to Knowledge & Information* | 2 | 15, 118 |

| Adaptability† | 1 | 118 | |

| Available Resources‡ | 1 | 118 | |

| Compatibility | 3 | 15, 57, 177 | |

| Complexity§ | 7 | 15, 30, 133, 177 | |

| Cost∥ | 4 | 15, 57, 133, 137 | |

| Engaging | 2 | 57, 137 | |

| Executing | 2 | 137, 177 | |

| External Policy & Incentives | 1 | 137 | |

| Knowledge & Beliefs about the Innovation¶ | 3 | 118, 133, 137 | |

| Implementation Climate | 2 | 137 | |

| Leadership Engagement | 2 | 137 | |

| Patient Needs & Resources # | 3 | 16, 129, 137 | |

| Networks & Communications** | 1 | 118 | |

| Planning | 2 | 15 | |

| Reflecting & Evaluating†† | 1 | 118 | |

| Facilitator | Access to Knowledge & Information* | 2 | 16, 118 |

| Adaptability | 1 | 177 | |

| Available Resources‡ | 6 | 15, 16, 57, 133 | |

| Cost∥ | 1 | 133 | |

| Executing | 1 | 177 | |

| External Policy & Incentives | 1 | 15 | |

| Formally Appointed Internal Implementation Leaders | 1 | 57 | |

| Knowledge & Beliefs about the Innovation¶ | 1 | 16 | |

| Patient Needs & Resources# | 1 | 118 | |

| Networks & Communications** | 3 | 15, 118, 177 | |

| Planning | 1 | 57 | |

| Readiness for Implementation‡‡ | 1 | 133 |

- *

Access to digestible information and knowledge about the innovation and how to incorporate it into work tasks.

- †

Degree to which an innovation can be adapted, tailored, refined, or reinvented to meet local needs.

- ‡

Level of resources organizational dedicated for implementation and on-going operations including physical space and time.

- §

Perceived difficulty of the innovation, reflected by duration, scope, radicalness, disruptiveness, centrality, and intricacy and number of steps required to implement.

- ∥

Costs of the innovation and costs associated with implementing the innovation including investment, supply, and opportunity costs.

- ¶

Individuals’ attitudes toward and value placed on the innovation, as well as familiarity with facts, truths, and principles related to the innovation.

- #

Extent to which patient needs, as well as barriers and facilitators to meet those needs, are accurately known and prioritized by the organization.

- **

Nature and quality of webs of social networks, and the nature and quality of formal and informal communications within an organization.

- ††

Quantitative and qualitative feedback about the progress and quality of implementation accompanied with regular personal and team debriefing about progress and experience.

- ‡‡

Tangible and immediate indicators of organizational commitment to its decision to implement an innovation.

Outpatient

We identified 30 studies of implementation of provider-to-provider telehealth for rural outpatient care. These studies all assessed consultations in which one provider, often a specialist, contributed to the diagnosis or management of a patient by another provider, often a primary care physician, nurse or someone lacking specialist certification or extensive experience with the condition or treatment. The barriers and facilitators are grouped and organized by clinical indication in Table B-8, and additional details can be found in Appendix Table D-10.

Five studies of multi-specialty programs included two statewide programs80, 135 and three programs serving a small group of clinics or a single health system.71, 102, 119 Psychiatric consultations were the subject of five studies of services that provided expert advice on a range of mental health issues including: medication therapy for opioid use disorder in a group of community clinics that are part of the Veteran Health Administration;24 advice on medications and treatment for children in a state Medicaid program,63 and programs to help diagnose adults and identify and arrange appropriate services.32, 62, 91 Five studies were of programs that provided consultations for different aspects of care related to long term services and supports including assessment of whether nursing home residents should be transferred to hospitals,64 oral health screening and teledentistry,162, 163 wound care,74 outpatient geriatric assessment and management,126 and pediatric hospice care.168 The remaining studies each evaluated consultations related to evaluating or managing patients with chronic conditions including cancer,69, 140 gastroenterology,54 dermatology,125 cardiology,116 nephrology,113 occupational screening of miners,43 and support for midwifes managing pre-eclampsia.171

Studies of multispecialty programs included assessments of how one program evolved from a pilot test to a statewide program over years with a mixture of sources of funding.80 An evaluation of a 10-year, multi-site initiative to increase access to care in rural areas in California through telehealth reported that organizational barriers contributed to a lack of networking across programs and lower uptake than expected of telehealth services.135 Both of these studies demonstrate how implementation and spread requires sustained efforts and commitments from multiple stakeholders and suggests that statewide or regional efforts can be effective. Questions among rural clinicians about whether telehealth was truly patient-centered were a barrier for teleconsultations in rural Sweden as some providers felt it may be easier to send patients to the hospital directly rather than delay hospitalization for a consult.71 Concerns cited in United States studies were echoed in studies in other countries. A program in Germany cited concerns about time, financing and changes to established workflows as barriers that could be addressed if systems were more usable and training provided.119 A program in Australia illustrated time concerns by documenting that teledermatology consultations take twice as long as in-person assessments and payment does not include this extra time. This program addressed this and other barriers by adding a telehealth coordinator who reduced the need for clinician time and by assuring technical support was available.102

Telehealth is often proposed as one solution to the shortage of mental and behavioral health providers and programs in rural areas. Some of the telehealth programs address specific treatments, such as the use of Buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in VA clinics in one state,24 while others are more general. The evaluation telehealth supported Buprenorphine was one of the few that used an implementation science framework to assess their experience and then translate this experience into an implementation tool kit that could be used by others to replicate the program. Another telehealth consult program provided medication review and treatment recommendations for children in a state Medicaid program.63 These programs had to overcome specific barriers including legal concerns related to prescribing and the need for consultants to understand resource availability in other locations. Another program used a continuous quality improvement approach to identify and make workflow adjustments to assure success.91 Psychiatric teleconsultation services in Ontario, Canada, one for adults62 and one focused on geriatric psychiatry32 identified fundamental gaps in organization and culture as barriers, such a lack of integration of the telehealth consultation with telephone and in person visits with the patient62 and a concern among providers that telehealth would allow the government to justify the lack of support for increasing local, in-person services for patients.32

The two articles on provider-to-provider telehealth for cancer care were both reports about the same program in Queensland, Australia. This program allowed chemotherapy to be administered in rural hospitals by local physicians and nurses supported by remote oncologists and chemotherapy nurses.69, 140 Starting with a pilot to demonstrate safety, the program expanded to six sites after addressing barriers including lack of role clarity and technology restrictions. Changes included assuring the iCamera could zoom sufficiently to allow checks on chemotherapy bags and provide good visuals during physical exams; structuring the program to provide professional development opportunities for rural nurses; and financial incentives for physicians to participate.

Long term care residents often have limited access to health care services for many reasons including resident’s/patient’s difficulties traveling and the fact that specialty services are rarely available onsite in nursing homes and other residential care and home-based long-term care. In this context, telehealth consultations and programs may offer services that would not otherwise be available. For example, a multisite program was established by a health system to provide acute assessment and care planning support in order to reduce patient transfers to hospitals.64 The program grew from 5 to 34 sites in 4 years by building on the health system’s experience with telehealth for other uses and working to change the culture from one that had defaulted to hospitalization to one that accepted treating residents in place. An oral health program provides another example in which a new service was made available. Residents who were not receiving dentistry services were screened by a technician who used a live intra oral camera to transmit images to a remote dentist who could assess what could be done on site and what required travel to a dentist.162, 163 This program was able to increase compliance with guidelines and regulations while increasing staff confidence in their ability to manage oral health. Other applications included a geriatric consult service in the Veterans Health Administration that was able to increase assessments by setting up both synchronous and asynchronous consultations.126 Implementation of a teleconsult program to support wound care by home and community providers revealed structural barriers to implementation including the need for staff computer literacy and the lack of use of standardized terminology by the home care nurses and consultants.74 Adding telehealth consultations to a pediatric hospice program underscored tradeoffs and challenges. The program demonstrated the ability to provide multidisciplinary, timely help to supplement in person care, but found that video consults were limited in their ability to assess family distress and that the consults risk prioritizing expert views over family needs.168

The remaining outpatient studies included one report each about telehealth consultations for different chronic, or not immediately acute conditions, including a regional cardiology program,116 chronic kidney disease consultations for an Indian Health Service clinic,113 a local gastroenterology program focused on a single condition,54 and a large dermatology program with 15 hubs in the VA.125 All these programs were designed to increase access and timeliness of care and all faced hurdles related to lack of staff support, space, and connectivity/bandwidth. Two less common approaches included adding telehealth to a mobile clinic that provides screening for coal miners43 and creating a phone app to supplement support to midwives managing pre-eclampsia in a rural area.171 Both of these programs had to overcome unique technical challenges, but faced common barriers related to limited connectivity.

Table B-8Findings of outpatient implementation studies

|

Topic Number of Studies Intervention |

Method N* Location | Facilitators | Barriers | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Multi-specialty 5 Programs that make consultations from a range of specialists available over video, phone or electronic records |

Stakeholder (patients and provider) surveys and interviews N=Not reported Statewide hub/spoke program in South Carolina80 Evaluation with surveys, site visits, documentation review, interviews N=10 organizations in 22 counties California135 Focus groups N=5 primary health-care centers; 19 health care personnel Sweden71 Interviews N=18; Physicians, administrators, medical students Germany119 Interviews N=10 expert providers of telehealth Australia102 |

|

|

|

|

Psych/Mental Health 7 Managing opioid use disorder, mental health care planning, for adults and medications and treatment for recommendations for children |

Interviews and case review N=3 Clinics; 19 interviews VA in Maine24 Continuous Quality Improvement Surveys, Chart reviews and program statistics N=1 health system Illinois91 Program records N=1 state Medicaid program Washington provision to Wyoming state Medicaid63 Chart reviews Interviews N=10 Ontario, Canada62 Chart review, patient and staff evaluations, survey to referring MDs, focus groups with community agencies GeroPsych service N=6 communities Ontario, Canada32 Focus group N=10 Psychiatrists and 4 psychologists across 3 states U.S. Washington, Michigan, Arkansas67 Questionnaire N=8 primary care providers, 4 psychologists Chile109 |

|

|

|

|

Cancer 2 Chemotherapy administration at remote sites |

Interviews N=1969 Patient records N=62140 Australia |

|

|

|

|

Long-Term Care 3 Acute illness; hospital transfer decisions |

Pilot Tests N=1 health system, up to 14 sites Avera Health, Several States64 Interview N=21 administrators and clinicians across 16 facilities U.S. Nationwide129 Interview N=8 Clinicians Germany95 |

|

|

|

|

Oral Health in Long-Term Care residencies 2 |

Chart review and program records, interviews and focus group |

|

|

|

|

Geriatrics 1 |

Program records N=12 hubs U.S. Veterans Health Administration126 |

|

|

|

|

Wound Care 1 |

Program records N=4 home and community health providers Australia74 |

|

| Not reported |

|

Pediatrics 2 |

Interview N=15 hospice nurses 1 Midwestern U.S. state168 Interview N=1 hub, 7 community health centers Australia89 |

|

| Not reported |

|

Chronic Conditions 1 Gastroenterology, care for inflammatory bowel disease |

Patient and program records N=99 patients Ontario, Canada54 |

|

|

|

|

Dermatology 2 Remote assessment and diagnosis |

EHR data, program reporting, online survey N=15 hubs U.S. Veterans Administration125 Survey N=34 Primary care providers U.S. Mississippi108 |

|

| Not reported |

|

Cardiology 1 Case review and remote exam |

Program review N=5 sites Minnesota, Wisconsin116 |

|

|

|

|

Nephrology 1 Care review and remote patient/provider appointment |

Program review N=1 site Zuni Pueblo, Indian Health Services113 |

|

| Not reported |

|

Screening 1 Mobile clinic: mining related exposure and general health |

Surveys N=278 (62%) of 4511 mobile clinic with telehealth for miners New Mexico43 |

|

|

|

|

Midwifery 1 Using phone app to managing pre-eclampsia |

Focus groups, N=18 midwives Scotland171 |

|

| Not reported |

- *

N is used here to represent the unit of analysis, which may be number of individual participants or may be number of health care sites or systems.

Abbreviations: EHR = electronic health record; IT = information technology; MD = medical doctor; U.S. = United States; VA = U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs.

Table B-9 provides a summary of the barriers and facilitators identified in studies of outpatient provider-to-provider telehealth for rural populations by the standardized constructs. As almost half of the studies included for Key Question 3 involved outpatient care, the counts of facilitators and barrier are higher. However, unlike inpatient care some constructs were identified much more frequently than others. Available resources was the most frequent barrier, cited 23 times. But others also mapped to higher numbers of cited barriers including compatibility (14) and access to knowledge and information (9). Available resources (15) and access to knowledge and information (15) were also cited as common facilitators (11 times), but other important facilitators included networks & communications(16) and patient needs & resource(9)s. In the case of this last category, a facilitator for use of telehealth was often patients’ needs for expertise and services that were not otherwise available without telehealth.

Table B-9Outpatient: barriers and facilitators by CFIR constructs

| Type | Facilitator or Barrier Name | Facilitator or Barrier Number of Mentions | Reference Number(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barrier | Access to Knowledge & Information* | 9 | 62, 67, 69, 74, 102, 129, 162 |

| Adaptability† | 2 | 62, 67 | |

| Available Resources‡ | 23 | 24, 32, 49, 64, 67, 69, 71, 74, 89, 91, 102, 109, 113, 125, 140, 162, 171 | |

| Compatibility§ | 14 | 64, 67, 69, 74, 80, 102, 108, 113, 119, 129, 135 | |

| Complexity∥ | 3 | 67, 74, 171 | |

| Cost¶ | 3 | 80, 116, 119 | |

| Engaging# | 5 | 24, 54, 71, 116, 135 | |

| Executing** | 10 | 32, 89, 108, 109, 119, 129, 140 | |

| External Policy & Incentives†† | 5 | 89, 102, 108, 125, 135 | |

| Implementation Climate‡‡ | 1 | 62 | |

| Knowledge & Beliefs about the Innovation§§ | 4 | 32, 119, 135 | |

| Leadership Engagement | 1 | 108 | |

| Networks & Communications¶¶ | 6 | 24, 67, 113, 125, 126, 129 | |

| Patient Needs & Resources∥∥ | 8 | 54, 62, 71, 129, 168 | |

| Planning## | 1 | 135 | |

| Readiness for Implementation*** | 3 | 24, 67, 119 | |

| Reflecting & Evaluating††† | 2 | 63, 135 | |

| Relative Priority‡‡‡ | 3 | 24, 32, 102 | |

| Facilitator | Access to Knowledge & Information* | 15 | 24, 32, 43, 62, 64, 69, 71, 74, 91, 125, 126, 135 |

| Adaptability† | 1 | 125 | |

| Available Resources‡ | 11 | 32, 62, 64, 113, 116, 119, 125, 140, 162 | |

| Compatibility | 1 | 109 | |

| Complexity∥ | 1 | 119 | |

| Cost¶ | 4 | 43, 91, 119, 163 | |

| Engaging# | 7 | 54, 62, 80, 119, 140, 168 | |

| External Policy & Incentives†† | 3 | 80, 140 | |

| Executing | 2 | 95, 109 | |

| Formally Appointed Internal Implementation Leaders§§§ | 3 | 54, 113, 135 | |

| Knowledge & Beliefs about the Innovation§§ | 1 | 32 | |

| Leadership Engagement∥∥∥ | 4 | 24, 125, 140 | |

| Patient Needs & Resources ∥∥ | 9 | 32, 43, 108, 113, 119, 126, 168, 171 | |

| Networks & Communications¶¶ | 16 | 32, 62, 67, 69, 80, 89, 95, 109, 113, 125, 126, 129, 135, 140, 162 | |

| Planning## | 4 | 64, 119, 135, 140 | |

| Readiness for Implementation*** | 5 | 24, 64, 80 | |

| Reflecting & Evaluating††† | 4 | 64, 91, 140, 163 | |

| Relative Priority‡‡‡ | 1 | 74 |

- *

Access to digestible information and knowledge about the innovation and how to incorporate it into work tasks.

- †

Degree to which an innovation can be adapted, tailored, refined, or reinvented to meet local needs.

- ‡

Level of resources organizational dedicated for implementation and on-going operations including physical space and time.

- §

Degree of tangible fit between meaning and values attached to the innovation by involved individuals, how those align with individuals’ own norms, values, and perceived risks and needs, and how the innovation fits with existing workflows and systems.

- ∥

Perceived difficulty of the innovation, reflected by duration, scope, radicalness, disruptiveness, centrality, and intricacy and number of steps required to implement.

- ¶

Costs of the innovation and costs associated with implementing the innovation including investment, supply, and opportunity costs.

- #

Attracting and involving appropriate individuals in the implementation and use of the innovation through a combined strategy of social marketing, education, role modeling, training, and other similar activities.

- **

Carrying out or accomplishing the implementation according to plan.

- ††

External strategies to spread innovations including policy and regulations (governmental or other central entity), external mandates, recommendations and guidelines, pay-for-performance, collaboratives, and public or benchmark reporting.

- ‡‡

Absorptive capacity for change, shared receptivity of involved individuals to an innovation, and the extent to which use of that innovation will be rewarded, supported, and expected within their organization.

- §§

Individuals’ attitudes toward and value placed on the innovation, as well as familiarity with facts, truths, and principles related to the innovation.

- ∥∥

Extent to which patient needs, as well as barriers and facilitators to meet those needs, are accurately known and prioritized by the organization.

- ¶¶

Nature and quality of webs of social networks, and the nature and quality of formal and informal communications within an organization.

- ##

Degree to which a scheme or method of behavior and tasks for implementing an innovation are developed in advance, and the quality of those schemes or methods.

- ***

Tangible and immediate indicators of organizational commitment to its decision to implement an innovation.

- †††

Quantitative and qualitative feedback about the progress and quality of implementation accompanied with regular personal and team debriefing about progress and experience.

- ‡‡‡

Individuals’ shared perception of the importance of the implementation within the organization.

- §§§

Individuals from within the organization who have been formally appointed with responsibility for implementing an innovation as coordinator, project manager, team leader, or other similar role.

- ∥∥∥

Commitment, involvement, and accountability of leaders and managers with the implementation of the innovation.

Telestroke and Emergency Care

One of the most commonly studied applications of provider-to-provider telehealth in rural areas is the diagnosis and management of stroke due to the higher prevalence of stroke and stroke risk factors in rural areas and treatments that require accurate diagnosis and timely administration.188, 189 The telestroke programs described in this section bridge ED and inpatient care as they include consultations as part of initial assessment and triage as well treatment decisions and care delivery. We did not identify studies of the implementation of EMS telestroke programs in which consultations focus on prehospital triage and decisions made in the field about where the patient should be transported.

Table B-10 provides an overview of seven studies (reported in eight articles)6, 7, 14, 28, 33, 77, 146 of facilitators, barriers and impact related to the implementation of telestroke programs (Additional details in Appendix Table D-10). All of the projects studied were hub-spoke models in which one or more hubs where specialists were located were connected with rural hospitals. Evaluations of these programs included studies of statewide programs in West Virginia6 and South Carolina,7, 146 case studies of networks around a single hub,33 a comparison of the early implementation of a network in South Carolina to one in Georgia147 and an assessment of a regional program in Australia.14, 28 One evaluation reviewed state laws and regulations in the United States.77

The telestroke implementation studies were of successful programs and the evaluations focused on the factors that supported this success. A case study comparing the early (1991) implementation in two networks reported that the networks had not integrated the technology into their care delivery processes and identified enablers which continue to be called out in other, more recent studies including: resource needs, the key role of performance monitoring and continuous improvement; the importance of a champion and dedicated coordinator at spokes, stakeholder involvement, and tangible goals such as stroke center certification147 A frequently cited approach included stepped or phased implementation that started with preliminary needs and workflow assessments to inform pilot tests; diversity of engagement and funding, including private and government support; the need for staff to support the program, and training; and the importance of ongoing evaluation and program improvement. Barriers were less frequently cited but included lack of sufficient IT support, lack of integration of records and patient data, and the prohibition on fees or additional reimbursement for telehealth infrastructure in some states. Reports on telestroke implementation also focused on the impact on care and organizational outcomes, citing fewer transfers and certification as a stroke center as motivation to continue to sustain and improve the programs.

We identified studies of implementation of provider-to-provider consultations for general emergency care, pediatric emergencies and psychiatric emergencies in addition to telestroke. Five studies were of models in which a remote specialist or emergency physician advises a generalist physician, nurse practitioner or nurse who staff a rural emergency room.88, 90, 150, 166, 180 Follow-up with rural EDs that did and did not use telehealth based on a United States national survey, found that 67% of nonusers had considered implementing telehealth but reported that the single most important reason the ED is not using telehealth was cost (37% of respondents), followed by technologic concerns and the assessment that telehealth is not needed to meet patient’s needs (11% each). Despite these barriers, six percent reported they had started to use telehealth since the original survey.180 Costs cited in this and other studies included the cost of technology but also the cost of the subscription services that provide access to the consultants. Additional barriers included rural providers lack of understanding of telehealth, lack of perception that telehealth will address a clear problem and perceptions that the motivation is to save money, particularly on personnel. For this particular use the identified facilitators were general satisfaction and having a telehealth coordinator who could handle scheduling and technology.

Two studies assessed implementation of telehealth specifically for pediatric emergencies.134, 170 One is an example of the few studies that compared different models; one model that provided only pediatric specialty consultations and one in which pediatrics was one of several specialties provided as part of a system wide consult service.170 This study found that both models were considered successful, but produced very different results as they served different populations. The specialist only model was used for more critical cases while in the other, pediatric consults were used less, but used for both high and low risk cases. As a result, perceptions and measures of the systems differed. These studies identified specific factors that were not emphasized in other studies, such as the need to test technology that is not in frequent use and the importance of building rapport and assuring telehealth fits in the culture of the practice.

Two studies in three articles assessed telehealth psychiatric consultations for patients presenting in EDs. One study evaluated two different network approaches to emergency psychiatric telehealth: a regional network, with assessments and consults available as part of a system that provides multispecialty consults for MI, stroke and other acute illnesses as well as behavior health, by pressing a button compared to a smaller, local system in which a behavioral health specialist was paged when needed.169 The assessment focused on patient characteristics and confirmed that both models increase access to inpatient care, but the evaluation did not explore detailed implementation differences in the systems. A study in northern Norway 160, 161 evaluated a system that made consultation available 24/7 by telephone and video; the study reported that using well established technology and having a safety net system supported the implementation and use of telehealth consults.

We identified one study that specifically addressed implementation of telehealth in prehospital care by EMS. A small study in Scotland94 reported several major barriers to the use of remotely guided ultrasound in prehospital care. These included a lack of evidence and lack of documented need for remote guided ultrasound as well as different perceptions of EMS personnel and consulting physicians about skills and priorities.

Table B-10Findings of telestroke and emergency care implementation studies

|

Topic Number of Studies Intervention |

Method N* Location | Facilitators | Barriers | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Telestroke 7 Hub:Spoke |

Registries and administrative Data N=2 statewide studies West Virginia6 Case study N=1 program South Carolina33 Case studies N=2 networks in South Carolina/ Georgia147 Case study including reports and interviews N=16 stakeholder reports, 13 funder reports, 10 protocols, 3 collaborative agreements, 93 meeting minutes Review of state statutes and regulations N=50 states United States77 |

|

|

|

|

Emergency Care: Non specific 6 Remote consultation Rural: Primary care provider, Nurse practitioner, nurse or generalist Consultant: Specialists or ED physician or nurse. |

Survey of rural EDs N=153/177 telehealth users;375/453 non users U.S.180 Surveys and hospital records Pre/Post implementation N=9 hospitals Mississippi150 EMR data, interviews, and site visits N=85 administrator at 26 rural hospitals South Dakota Avera Health166 Financial data, interviews, site visits N=1 emergency system; 49 rural hospitals, same interviews as Ward above South Dakota Avera Health90 Interviews N=12 New Zealand88 Program evaluation N = 206 patient records Australia123 |

|

|

|

|

Emergency Care: Pediatrics 2 Pediatrics as part of multispecialty consults service; Dedicated pediatric service |

Two models (University of California Davis-specialty/hub vs. Advera -general ED including pediatrics) N=30 hospitals; 15 each170 Survey based on themes from interviews N=7 hospitals, 48 interviews, surveys 5 hospitals 104 (34%) of 306 clinicians invited University of Pittsburgh134 |

|

|

|

|

Emergency Care: Psychiatrics 2 studies (3 articles) |

Compare 2 ED Behavioral Health Models N=19 spoke hospitals; 2 networks) U.S. Midwest169 Interviews N=29 |

|

|

|

|

EMS: Ultrasound 1 |

Interviews N=12 Scotland94 |

|

| Not reported |

- *

N is used here to represent the unit of analysis, which may be number of individual participants or may be number of health care sites or systems.

Abbreviations: ED = emergency department; EMS = emergency medical services; EMR = electronic medical record; IT = information technology; NP = nurse practitioner; PA = physician’s assistant; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator; U.S. = United States.

These barriers and facilitators are presented according to the CFIR constructs in Table B-11. The barriers are distributed across constructs, with mosted cited one to three times. The most frequently identified category of barrier was knowledge & beliefs about the innovation with this cited five times. The facilitators were more concentrated in categories that were also frequent in in- and out-patient studies; access to knowledge and information (11), available resources (9), and patient needs & resources (7). One construct that was more frequent in emergency care was engaging (7) which represents including the right people in the implementation, which may respresent the need for emergency care to coordinate activities and processes across organizations such as EMS, multiple hospitals and outpatient care.

Table B-11Emergency care: barriers and facilitators by CFIR constructs

| Type | Facilitator or Barrier Name | Facilitator or Barrier Number of Mentions | Reference Number(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barrier | Access to Knowledge & Information* | 2 | 28, 88 |

| Adaptability† | 1 | 170 | |

| Available Resources‡ | 4 | 88, 134, 170 | |

| Compatibility§ | 4 | 94, 134, 180 | |

| Cost∥ | 1 | 180 | |

| Executing¶ | 2 | 28 | |

| External Policy & Incentives# | 1 | 77 | |

| Implementation Climate** | 1 | 88 | |

| Knowledge & Beliefs about the Innovation†† | 5 | 94, 170, 180 | |

| Networks & Communications‡‡ | 2 | 88, 123 | |

| Readiness for Implementation§§ | 3 | 88, 180 | |

| Relative Priority∥∥ | 3 | 28, 94, 180 | |

| Facilitators | Access to Knowledge & Information* | 11 | 7, 14, 28, 33, 88, 134, 146, 147 |

| Available Resources‡ | 9 | 7, 14, 33, 88, 147, 166, 169, 170 | |

| Cost∥ | 2 | 77, 90 | |

| Engaging¶¶ | 7 | 14, 28, 33, 147 | |

| Executing¶ | 1 | 33 | |

| External Policy & Incentives# | 4 | 14, 77 | |

| Formally Appointed Internal Implementation Leaders## | 3 | 14, 33, 147 | |

| Implementation Climate** | 3 | 28, 94, 147 | |

| Knowledge & Beliefs about the Innovation†† | 1 | 170 | |

| Leadership Engagement*** | 4 | 28, 123, 147 | |

| Patient Needs & Resources††† | 7 | 6, 7, 88, 150, 160, 161 | |

| Networks & Communications‡‡ | 4 | 6, 94, 170 | |

| Planning‡‡‡ | 2 | 28, 147 | |

| Readiness for Implementation§§ | 5 | 7, 14, 33, 147 | |

| Reflecting & Evaluating§§§ | 4 | 14, 146, 147 |

- *

Access to digestible information and knowledge about the innovation and how to incorporate it into work tasks.

- †

Degree to which an innovation can be adapted, tailored, refined, or reinvented to meet local needs.

- ‡

Level of resources organizational dedicated for implementation and on-going operations including physical space and time.

- §

Degree of tangible fit between meaning and values attached to the innovation by involved individuals, how those align with individuals’ own norms, values, and perceived risks and needs, and how the innovation fits with existing workflows and systems.

- ∥

Costs of the innovation and costs associated with implementing the innovation including investment, supply, and opportunity costs.

- ¶

Carrying out or accomplishing the implementation according to plan.

- #

External strategies to spread innovations including policy and regulations (governmental or other central entity), external mandates, recommendations and guidelines, pay-for-performance, collaboratives, and public or benchmark reporting.

- **

Absorptive capacity for change, shared receptivity of involved individuals to an innovation, and the extent to which use of that innovation will be rewarded, supported, and expected within their organization.

- ††

Individuals’ attitudes toward and value placed on the innovation, as well as familiarity with facts, truths, and principles related to the innovation.

- ‡‡

Nature and quality of webs of social networks, and the nature and quality of formal and informal communications within an organization.

- §§

Tangible and immediate indicators of organizational commitment to its decision to implement an innovation.

- ∥∥

Individuals’ shared perception of the importance of the implementation within the organization.

- ¶¶

Attracting and involving appropriate individuals in the implementation and use of the innovation through a combined strategy of social marketing, education, role modeling, training, and other similar activities.

- ##

Individuals from within the organization who have been formally appointed with responsibility for implementing an innovation as coordinator, project manager, team leader, or other similar role.

- ***

Commitment, involvement, and accountability of leaders and managers with the implementation of the innovation.

- †††

Extent to which patient needs, as well as barriers and facilitators to meet those needs, are accurately known and prioritized by the organization.

- ‡‡‡

Degree to which a scheme or method of behavior and tasks for implementing an innovation are developed in advance, and the quality of those schemes or methods.

- §§§

Quantitative and qualitative feedback about the progress and quality of implementation accompanied with regular personal and team debriefing about progress and experience.

Education/Mentoring

Table B-12 includes a summary of information from 13 studies or reports on the use of telehealth for training and mentoring health care providers in rural areas (Additional details in Appendix D-10).

Nine of these studies are assessments of ECHO programs. ECHO combines didactic training, case presentations, virtual clinics and peer support to increase capacity and quality of care.9, 56, 73, 115, 127, 144, 157, 174 The ECHO programs evaluated in these articles address different topics with four focused on pain or opioids,56, 73, 144, 157 one each about Hepatitis C,127 Multiple Sclerosis,9 and HIV in pregnancy,115 and one program that implemented ECHO as part of a larger expansion of specialist care.174 While the subject matter and scale of these programs differed, facilitators, challenges and impact were similar. A frequently cited barrier was lack of clinician time to attend sessions or issues with scheduling. The evaluations also acknowledged that while ECHO could increase provider knowledge and skills it could not address all policy and practice barriers to practice change. Most ECHO program evaluations report a high level of stakeholder support and that the programs address rural participants needs for peer interaction, current knowledge, and access to experts. Evaluations of the impact of ECHO programs have documented that participants have changed practice, managed patients they would have referred, engaged in consultations with the expert faculty outside of the ECHO program, and become resources for other providers in their communities.

The three additional evaluations all address the rural clinicians’ need for training in emergency care. One evaluation documented how training could be incorporated into consultations, reporting how this assured training was useful and relevant.183 An experimental study tested whether training medical students using simulations for relatively rare emergency procedures could be managed by a remote expert trainer and documented that this was feasible and produced similar educational outcomes.68 An assessment of remote training for emergency care in Australia documented that training could reduce professional isolation, but that sometimes topics were not relevant to rural working conditions.121

Table B-12Findings of education and mentoring implementation studies

|

Topic Number of studies Intervention |

Method N Location | Facilitators | Barriers | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ECHO 9 Program with remote training, case reviews/clinics and peer interaction ECHO as part of a comprehensive program including e-consults |

Hepatitis C Survey to participants and non N=32 of 72 contacted; 15 facilities; Indian Health Service127 Multiple Sclerosis Pre questionnaire, program manager observations, exit interviews focused on case presentations N=8 of 24 clinicians, 13 practice sites; Mississippi, Washington State, Alaska, Montana, Idaho9 HIV in pregnancy Survey and review of cases N=41 of 53 surveys, 11 cases Perinatal HIV; Washington State, Alaska, Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Colorado115 Chronic Pain Content analysis N=Random selection of 25 of 67 cases; 406 data units; U.S. Connecticut. Single federally qualified health center157 Buprenorphine Interviews N=20; U.S. North Carolina144 Pain and Opioid Management with 2–3 in person supplemental training Questionnaires and focus groups N=38 participants; 2 workshops; New Mexico Indian Health Service73 Cancer Pain Survey of participants and non-participants N=24(46%) who attended education; 32 (34%) who attended case conferences; U.S. New Mexico56 Multiple Topics Surveys of clinician leads, administrative data N=180 from 87 sites; U.S. VA174 Melanoma Survey N = 10 Primary care providers; U.S. Missouri17 |

|

|

|

|

Telehealth Training 3 Training incorporated as part of the consultation183 Simulation training lead by remote expert68 Training needs assessment121 |

Emergency Care Interviews N=18 hospitals Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota Avera tele-training during consultation183 High-Acuity Low-Occurrence Procedures Assessments N=69 medical students Randomized to telehealth, in person and no training Newfoundland, Canada68 Emergency Care Interviews N=20 rural physician Australia121 |

|

|

|

|

Structured Dentist Network 1 |

Dentistry Interview and focus group N= 2 Dental specialists and 8 General dentists Australia83 |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: ECHO = Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; U.S. = United States.

While telehealth interventions for education and mentoring differ in format and outcomes from those that are targeted to care of a specific patient, barriers and facilitators were able to be mapped to CFIR constructs as the framework was designed to be applicable across different types of interventions. Table B-13 summarizes these. The most frequently cited barrier was compatibility (8), being when education did not correspond to the need or environment of the trainees. Not surprisingly, the most common facilator was access to knowledge and information (11) as the telehealth education and mentoring programs were more likely to be implemented when they provided accessible information that could be directly incorporated into the trainees tasks and environment.

Table B-13Education/mentoring: barriers and facilitators by CFIR constructs

| Type | Facilitator or Barrier Name | Facilitator or Barrier Number of Mentions | Article Reference IDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barrier | Access to Knowledge & Information* | 3 | 73, 83 |

| Adaptability* | 1 | 121 | |

| Available Resources‡ | 4 | 56, 73, 83, 127 | |

| Compatibility§ | 8 | 121, 127, 144, 183 | |

| External Policy & Incentives∥ | 2 | 144 | |

| Implementation Climate¶ | 3 | 121, 127 | |

| Knowledge & Beliefs about the Innovation# | 1 | 144 | |

| Leadership Engagement** | 1 | 144 | |

| Planning | 1 | 83 | |

| Facilitator | Access to Knowledge & Information* | 12 | 17, 121, 127, 144, 174, 183 |

| Adaptability* | 2 | 56, 174 | |

| Available Resources‡ | 2 | 68, 121 | |

| Compatibility§ | 2 | 121, 174 | |

| Engaging†† | 3 | 157, 174 | |

| Implementation Climate¶ | 3 | 73, 144, 174 | |

| Leadership Engagement** | 2 | 174 | |

| Patient Needs & Resources‡‡ | 5 | 9, 115, 121, 127 | |

| Networks & Communications§§ | 6 | 17, 83, 127, 157, 174, 183 | |

| Reflecting & Evaluating∥∥ | 1 | 174 | |

| Relative Priority¶¶ | 1 | 174 |

- *

Access to digestible information and knowledge about the innovation and how to incorporate it into work tasks.

- †

Degree to which an innovation can be adapted, tailored, refined, or reinvented to meet local needs.

- ‡

Level of resources organizational dedicated for implementation and on-going operations including physical space and time.

- §

Degree of tangible fit between meaning and values attached to the innovation by involved individuals, how those align with individuals’ own norms, values, and perceived risks and needs, and how the innovation fits with existing workflows and systems.

- ∥

External strategies to spread innovations including policy and regulations (governmental or other central entity), external mandates, recommendations and guidelines, pay-for-performance, collaboratives, and public or benchmark reporting.

- ¶

Absorptive capacity for change, shared receptivity of involved individuals to an innovation, and the extent to which use of that innovation will be rewarded, supported, and expected within their organization.

- #

Individuals’ attitudes toward and value placed on the innovation, as well as familiarity with facts, truths, and principles related to the innovation.

- **

Commitment, involvement, and accountability of leaders and managers with the implementation of the innovation.

- ††

Attracting and involving appropriate individuals in the implementation and use of the innovation through a combined strategy of social marketing, education, role modeling, training, and other similar activities.

- ‡‡

Extent to which patient needs, as well as barriers and facilitators to meet those needs, are accurately known and prioritized by the organization.

- §§

Nature and quality of webs of social networks, and the nature and quality of formal and informal communications within an organization.

- ∥∥

Quantitative and qualitative feedback about the progress and quality of implementation accompanied with regular personal and team debriefing about progress and experience.

- ¶¶

Individuals’ shared perception of the importance of the implementation within the organization.

- Results - Improving Rural Health Through Telehealth-Guided Provider-to-Provider ...Results - Improving Rural Health Through Telehealth-Guided Provider-to-Provider Communication

- PCORI Methodology Standards Checklist - Treatment of Stages I-III Squamous Cell ...PCORI Methodology Standards Checklist - Treatment of Stages I-III Squamous Cell Anal Cancer: A Systematic Review

- Sample Abstract and Full-Text Review Forms - Evaluation and Treatment of Cryptor...Sample Abstract and Full-Text Review Forms - Evaluation and Treatment of Cryptorchidism

- Physiologic Predictors of Severe Injury: Systematic ReviewPhysiologic Predictors of Severe Injury: Systematic Review

- Diagnosis of GoutDiagnosis of Gout

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...