F.1. Introduction

During consultation on the draft version of the full guideline, stakeholder comments were received which raised a number of significant issues in relation to the guideline scope and recommendations developed in the guideline.

Stakeholders had concerns that because the guideline did not present a complete stroke rehabilitation patient pathway this may lead to services being reduced or even withdrawn. Stakeholders also noted the agreed approach to rehabilitation was a holistic one that reflected individual patient need provided by a multidisciplinary team but this was not considered by the guideline which had focused only on the delivery of interventions.

In light of the comments received from stakeholders, the GDG agreed that additional work would be carried out to address the structure and process of stroke rehabilitation which had not been included in the original draft version (or reference would be made to other NICE guidance). This was done to produce a more complete piece of guidance that would be useful to health professionals who deliver rehabilitation to a stroke population.

The evidence base is weak or absent for many of the areas stakeholders wished the guideline to include, therefore a different methodology was necessary that would provide a robust process to enable the GDG to make further recommendations. Where there was a lack of published evidence the NCGC technical team used a modified Delphi method (anonymous, multi-round, consensus-building technique) based on other available guidelines or expert opinion. This type of survey has been used successfully for generating, analysing and synthesising expert view to reach a group consensus position. The resulting statements will form the basis for the GDG to consider and utilise to develop further recommendations.

Whilst the stakeholder consultation clearly showed a concern that recommendations had not been made for particular areas of the rehabilitation pathway, the results of the Delphi survey have demonstrated that for many of these areas there does not appear to be consensus agreement held by the wider stroke rehabilitation professional body.

A process and protocol framework was drawn up for this additional work which was published on the NICE website (http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG/Wave21/4/FinalProtocol/pdf/English) and is added here as Appendix B.

The modified Delphi process and areas that are covered by it are detailed below.

It is important to emphasise that a search was conducted for systematic reviews on any of the additional topics that were identified by stakeholders. Where there were good quality systematic reviews identified, the evidence was updated (i.e. searches from the cut-off dates of the reviews) and findings were presented to the GDG. The GDG based their recommendations on this evidence. Reviews were identified for goal setting, stroke units, fitness and management of aphasia. Modified Delphi – areas to address

The following areas were identified as additional topics. These were prioritised based on stakeholders’ comments received during the consultation period of the guideline:

- Service delivery, multidisciplinary team working

- Assessment for rehabilitation, care planning, goal setting, and ongoing review of patients.

- Transfer of care, discharge planning and interface between health and social care

- Long term health and social support for people after stroke.

- Visual impairment including Diplopia

- Speech and language therapies –dysphasia, dysarthrophonia and articulatory dyspraxia

- Shoulder pain

F.2. Modified Delphi methodology

For review areas where little or no evidence was identified, a modified Delphi survey method15,30 was adopted. In NICE processes, little or no evidence for reviews is an exceptional circumstance when formal consensus techniques (such as the Delphi method) can be adopted22. For this guideline a full process and protocol framework was drawn up which can be found in Appendix A. Two external, independent experts were recruited to act as consultants in the development of the survey statements. The consultant experts’ role was to provide guidance to the technical team in the formulation and validation of consensus statements at each round of the survey. They neither took part in the survey nor the GDG meeting in which recommendations were drawn up from the Delphi consensus statements.

Delphi statements were distilled from the content of existing national and international stroke rehabilitation guidelines. The identified guidelines were quality assured by two research fellows using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument as described in the Appendix B. In this process the topic ‘goal setting’ was an exception since a systematic review was identified covering this issue. However, after presenting the evidence from this review to the GDG they came to the conclusion that important aspects of goal setting in clinical practice were not captured. To be able to draw up further recommendations regarding this topic it remained in the Delphi. The relevant sections of the guidelines were summarised and these summaries were used as the basis for draft statements. Statements were then discussed and revised with the recruited experts. Additional statements were drafted by the expert consultants with the technical team for areas where no existing guidance was available (e.g. interface between health and social care). Please see the appendicised table outlining the mapping process.

The Delphi panel comprised of stroke rehabilitation clinicians and other professionals with significant experience in stroke rehabilitation (referred to as the expert panel) covering a wide range of disciplines involved in stroke care. Members of the panel were identified by means of nomination, where each Guideline Development Group member had the option to nominate a maximum of 10 experts (providing name, work setting, discipline, area of expertise and contact details). These nominations were then collated and reviewed by the chair of the GDG and the RCP Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party and, after removal of duplicates, inspected for representativeness. There was an under-representation of social workers and orthoptists and organisations were directly contacted to nominate potential participants. In the first instance 164 experts were contacted and invited to participate. The list comprised:

- 6 geriatricians

- 9 neurologists

- 12 nurses

- 9 occupational therapists

- 8 people from patient representation/organisations: 7 were employees from patient organisations and 1 was a GDG patient representative (3 of those came employed by the Stroke Association, 3 from Different Strokes, one person from Speakability)

- 49 physiotherapists

- 6 psychologists

- 7 research/policy makers

- 9 social workers

- 16 speech and language therapists

- 19 stroke physicians

- 14 ‘other’ health care professionals (e.g. orthoptist, dietician, GP and pharmacists).

A survey, consisting of 68 statements plus 3 demographic questions (profession, setting, and geographic area), was then circulated to the expert panel. This survey included open text options in which panel members could give comments to statements. 116 panel members (69%), with representatives from all professions, responded to the survey. Participants were asked to comment on and rate how much they agreed with statements via an online survey. Comments from round 1 were then used to revise and refine the entire set of Delphi statements as is done in the usual piloting process of survey design. This process was carried out in conjunction with the consultant experts as well as the Chair of the guideline.

The new survey (round 2) was then sent out to the whole panel of 164 experts. In round two 89% (103/116) of panel members who took part in the first round responded, 83% (85/103) took part in round 3 and 86% (75/85) in round 4. Detailed statistics on each round could be found in Delphi Methodology Appendix 3. Throughout this process the group that participated stayed broadly representative of the panel that was originally identified. Details of group membership in each of the rounds can be obtained from the National Clinical Guideline Centre stroke guideline technical team demand. There was an option to decline to participate in Round 1 five members and in Round 2 six panel members declined to take part. The survey included a general set of statements to be rated by all panel members, as well as specialist topics (shoulder pain, speech and language management and visual impairments) targeted at those with particular experience in this field of expertise. These sections could be skipped by panel members without specific experience in these areas. For the majority of all 69 statements (plus demographics), a Likert scale was applied to indicate the level of agreement. Some statements employed multiple choice options. A four option Likert scale was used: strongly disagree, disagree, agree and strongly agree. A rate of 70% or higher of particpants ‘strongly agreeing’ was set for rounds 1 and 2, with this threshold for consensus being reviewed in rounds 3 and 4. In analysing the data, and in understanding the difficulty of reaching consensus in the latter rounds where iteration had featured, a decision was reached by the technical team to accept a rate of 67% ‘strongly agree’ as consensus as long as the majority of other participant responses were ‘agree’ and less than 10 of panel members disagreed. This was a pragmatic response by the technical team and meets published criteria that consensus is achieved when at 66.6% of an expert panel agrees. Statements that reached these levels would not feature in the next round. Statements that did not reach this level were reviewed by the technical team with the GDG chair and expert consultants and were amended based on the panel’s comments in the survey. This procedure of re-evaluation continued until either the consensus rate was achieved or until the experts no longer modified their previous estimates/responses (or comments). There is not complete agreement about the termination of Delphi and one researcher has stated ‘if no consensus emerges, at least a crystallizing of the disparate positions usually becomes apparent’ (Gordon, 1971)16.

When there were low levels of disagreement, some statements were not edited and re-included in the next round. With already low levels of disagreement it was felt that re-inclusion of these statements would encourage panel members to shift from an ‘agree’ to a ‘strongly agree’ response. This process lead to a survey with eleven statements in round 4. None of them reached the level of agreement specified for consensus, even with revision in previous rounds. A joint meeting of the technical team with the expert advisors and the chair of the guideline the results for the remaining 11 questions were discussed. Due to the fact that despite rephrasing levels of agreement had not changed it was decided that experts no longer modified their responses for this set of questions and that therefore consensus was unlikely to be achieved with further revision. In other words when both the level of agreement and the type of comments no longer changed it was agreed that a further round would not achieve consensus. The comments that illustrated these differences in opinions or comments that showed agreement but no longer changed were then highlighted in the final Delphi report.

How and when consensus was achieved for all statements in rounds 2 to 4 is presented in the appendices.

Since there was an over-representation of physiotherapists in the panel responses were inspected by profession in the analysis. There were no systematic differences in physiotherapists’ responses compared to those of other professions. Hence further details of responses per profession were not included in the report.

F.3. Qualitative analysis

A free text box was available for panel comments for each statement. Members of the panel used these text boxes frequently. Rates of comments ranged between 7–20% of for some items gaining early consensus, and up to 60% for items that were more controversial. For some items direct prompts were provided (e.g. ‘list the possible role of a MDT co-ordinator’) and most panel members commented providing additional items, i.e. with a rate if 60% or higher.

Overall comments fell into several categories:

- Those highlighting particular issues related to the clarity of the statement.

- Those criticising/or disagreeing with the statement content.

- Those providing additional options/approaches to those given in the statement (whether or not prompted).

- Those giving additional or qualifying information to the content of the statement.

Comments in category 1 were discussed after each round to inform possible changes to the statement for the next round. The technical team discussed these with the external consultants and Chair of the guideline and agreed on changes to the statements based.

When additional options were given by panel members (category 2 above), the frequency of comments (e.g. how often people mentioned a particular additional assessment) was inspected and applicability was discussed in the technical team meeting. Sometimes the frequency of mention clearly indicated a missing option which needed to be included in the list for the next round. However, frequency was not regarded as the only indicator for further inclusion the technical team also inspected idiosyncratic responses. Some suggested items were discussed but were deemed not to be a high priority for inclusion in the next round. Suggestions that did not feature in later rounds are provided in the Tables below in the relevant comments section.

Category 3 comments were reviewed using discourse analysis. As a starting point the most frequent keywords were inspected using the survey text analysis feature. The survey software provides a visual representation of keywords with more frequently produced items indicated by larger font size (the so called ‘cloud’). It was then checked whether these words/concepts could correspond to identifiable themes. In cases where the cloud was not found to be useful category 3 comments were carefully inspected and thematically interpreted. Representative comments or extracts from comments are frequently provided in the tables of results below. The themes and individual points that were raised by panel members were then discussed in the technical team meeting with the external consultants and Chair of the guideline.

For results of the qualitative analysis please refer to the final column of the consensus and non-consensus statement tables.

F.4. Service delivery - multidisciplinary team working

F.4.1. Consensus protocol

Table 1What should be the constituency of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation team and how should the team work together to ensure the best outcomes for people who have had a stroke?

| Population | Adults and young people 16 or older who have had a stroke |

|---|---|

| Components |

|

| Outcomes |

|

F.4.2. Multidisciplinary team working

F.4.2.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 2Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | A core stroke rehabilitation team should comprise of membership from the following disciplines: | 28/101 (28%) panel members commented Pharmacists and Nutritionist did not reach consensus Some other ‘optional’ team members were suggested in comments, for instance:

The importance of voluntary sector involvement was stated with regards to the role of a co-ordinator (“This role could be provided by the voluntary sector, the best example being the Stroke Association’s information, advice and support coordinators.”). | |

| • Consultant neurology/stroke medicine | 81.0 | ||

| • Nursing | 89.1 | ||

| • Physiotherapy | 99.0 | ||

| • Occupational therapy | 99.0 | ||

| • Speech and Language Therapy | 99.0 | ||

| • Clinical Neuro Psychology | 74.0 | ||

| • Rehabilitation Assistant | 72.2 | ||

| • Social work | 71.2 | ||

| 2. | Throughout the care pathway roles and responsibilities of the multi-disciplinary stroke rehabilitation team services should be clearly outlined, documented and communicated to the patient and their family. | 72.7 | 18/99 (18%) panel members commented Information to the family of the person who has had a stroke should only be given with patient’s consent Communication was viewed as integral in rehabilitation process Extracts: ‘Verbal communication should be supported by clear, unambiguous written information to avoid any subsequent disputes/confusion.’ ‘I think it helps communication for patients and staff, however the frequency and process of this has to be realistic in its delivery.’ |

| 3. | In order to inform and direct further assessment, members of the MDT should screen the person who has had a stroke for a range of impairments and disabilities. | 81.0 | 9/100 (9%) commented: Reliability and validity of screening instruments was highlighted Reason for screening: Screening to inform treatment/further assessment rather than screening for screening’s sake Treatment: Some people commented that the focus in stroke rehabilitation should be on treatment rather than measurement. |

F.4.2.2. Delphi statement where consensus was not reached

Table 3Table of ‘non-consensus’ statements with qualitative themes of panel comments

| Number | Statement | Results | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The person who has had a stroke is integrated in the stroke rehabilitation team. | 62.9 | 26/100 (26%) panel members commented in round 2; 29/84 (35%) commented in round 3 and 24/70 (34%) commented in round 4: Impairments of the persons who have had a stroke that affect participation should be considered for this statement. (“Some individuals can easily make a very active and substantial contribution to the work of the team whereas others because of the severity of the stroke or of any communication difficulties would be much more limited.”) Patient preference: It may not be the wish of the person who has had a stroke to participate in the team (“When I need care or help I wish to be treated with respect, dignity and as an equal, but I view the MDT as people who support me, advise me and have clinical expertise, they are the team who help me.”). Between rounds 3 and 4 the statement was changed from: ‘is a member of’ to ‘is integrated in’ the stroke rehabilitation team’. Most panel members objected to the concept of team membership. The concept of membership as opposed to partnership was highlighted Two panel members expressed the opinion that this statement was redundant. |

| 2. | A member of the multidisciplinary stroke rehabilitation team should be tasked with coordination and steering (e.g. communication, family liaison and goal planning) of the rehabilitation of the person who has had a stroke at each stage of the care pathway. | 62.5 | A direct prompt was given for this question (to list the roles). In round 2 61/100 (61%) panel members commented; 48/85(56%) in round 3 and 34/72 (47%) in round 4: There was a list of possible roles for a coordinator:

“where a member of the team is responsible, the process becomes slowed down.” |

F.5. Assessment for rehabilitation, goal setting and care planning

F.5.1. Consensus protocol

Table 4In planning rehabilitation for a person after stroke what assessments and monitoring should be undertaken to optimise the best outcomes?

| Population | Adults and young people 16 or older who have had a stroke |

|---|---|

| Components |

|

| Outcomes |

|

F.5.2. Assessment for rehabilitation

F.5.2.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 5Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | After admission to hospital the person who has had a stroke should have the following assessed as soon as possible: | 34/100 (34%) panel members commented: A number of additional assessments/measurements were suggested (a lot of these are covered in other sections):

| |

| • Positioning | 82.0 | ||

| • Moving and handling | 92.0 | ||

| • Swallowing | 94.9 | ||

| • Transfers | 79.5 | ||

| • Pressure area risk | 90.0 | ||

| • Continence | 86.8 | ||

| • Communication | 80.0 | ||

| • Nutritional status | 77.7 | ||

| 2. | Comprehensive assessment takes into account: | 25/100 (25%) panel members commented: Additional issues to take into account:

| |

| • Previous functional status | 86.1 | ||

| • Impairment of psychological functioning | 81.1 | ||

| • Impairment of physiological body functions and structures | 81.1 | ||

| • Activity limitations due to stroke | 84.1 | ||

| • Participation restrictions in life are stroke | 75.2 | ||

| • Environmental factors (social physical and cultural) | 76.2 | ||

| 3. | Family members and/or carers should be informed of their rights for a carers’ needs assessment. | 71.7 | 11/99 (11%) panel members commented: This was generally viewed as an important issue. Extracts: ‘Those carers who are passive need to be informed that this is available and many may be too timid to know they can request this assessment.’ |

| 4. | The impact of the stroke on the person’s family, friends and/or carers should be considered and if appropriate they can be referred for support. | 78.0 | 11/100 (13%) panel members commented: Comments were divided:

|

| 5. | People who have had a stroke should have a full neurological assessment including cognition, vision, hearing, power, sensation and balance. | 69.0 | 19/84(23%) panel members commented: This was a statement that was added in Round 3 based on comments in Round 2. Comments to this statement were – more individual than in themes:

|

| 6. | Experts agreed with screening for the following: | In round 2 this was an open text question and 83 people answered; in round 3 this was rephrased into a statement with multiple options format and 18/83 (22%) commented: There was confusion about some of the options and additional screening tools were suggested:

| |

| • Mood | 69.8 | ||

| • Pain | 68.6 | ||

| 7. | Routine collection and analysis of a range of measures should include: | In round 2 – 40/87 (46%) panel members commented; 26/77(34%) in round 3. This was included in a different format in Round 3 (to select the three main). Those that did not reach consensus were:

Others panel members highlighted that measures depend on the stage of rehabilitation (“NIHSS is a reasonable baseline whereas the Berg is most useful beyond the acute phase. It also depends on what sort of ‘analysis’ you are expecting to be done. Is the data for understanding the severity of stroke or the outcome of rehab?”) It was questioned whether the statement refers to outcome or baseline measures (“…It depends what you are trying to show? If it’s outcomes and service demands? Maybe rehab complexity scales to show the demands and resources you need. FIM to show functional outcomes perhaps instead of Barthel.”). Additional measures were also suggested:

| |

| • National Institute of Health Stroke Scale | 74.0 (of 50) selected as first option | ||

| • Barthel Index | 46.5 (of 43) - as second option | ||

| • Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) | 56.3 (of 32) as third option | ||

F.5.2.2. Delphi statement where consensus was not reached

Table 6Table of ‘non-consensus’ statements with qualitative themes of panel comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The specific list of professional screening tools to be included: | In round 2 – 48/93 (52%) panel members commented; 40/72(56%) in round 3 – the options changed between rounds 2 and 3: A number of additional scales/tools were mentioned [some of which were already included in other statements]:

“The tool is not important so long as it is a validated tool. There is no need to direct which tools people should use.”) Concern was raised about possible recommendations being too prescriptive (“These tools should only be suggested tools not prescriptive as the clinician should be able to make the decision as to the most appropriate tool”. “The tool is not important as long as it is a validated tool. There is no need to direct which tools people should use”.) Whether these were screening tools or outcome measures was also questioned. | |

| • Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) | 25.4 | ||

| • Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test (FAST) | 22.5 | ||

| • Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) | 42.6 | ||

| • The Waterlow Pressure score risk assessment tool (pressure ulcers) | 44.9 | ||

| 2. | Data collection should be overseen by a national body. | 62.0 | In round 2 – 27/97 (28%) panel members commented; 21/81(26%) in round 3 and 16/71 (23%) in round 4: It was highlighted that this is already in existence in some place (such as the RCP audit, the Scottish Stroke Care Audit or the National Sentinel Stroke Audit) |

F.5.3. Goal Setting

F.5.3.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 7Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Both profession specific as well as multidisciplinary stroke teams’ goals should be person focused. | 81.8 | 17/99 (17%) panel members commented This was seen important in the process of goal planning by some panel members (“Absolutely. We don’t do this enough yet and we need to get much better at this to use outcome measures properly and really effectively.”) It was seen as most important that goals should be set by or set collaboratively with the person who has had a stroke (“Goals need to be genuinely person generated.” “Goal setting should be collaborative, set with the patient, and multidisciplinary rather than uni-disciplinary” “There should be one set of patient agreed patient centred goals”) Four people expressed the opinion that this was not a sensible statement. | |

| Efforts should be made to establish the wishes and expectations of the person who has had a stroke and their carer/family. | 86.9 | 13/99 (13%) panel members commented It was highlighted that these expectations need to be realistic. Some people questioned the term ‘efforts’ and what this would mean in real terms. One person indicated the opinion that this was a redundant statement. | |

| The following criteria should be used when setting goals with the person who has had a stroke: | 20/100 (20%) panel members commented Rather than themes individual issues were highlighted: The type of goal depends on the stage and setting of rehabilitation (“Initial goals in the acute setting may be less focussed on activities and participation as the treatment begins to develop a base from which further goals may be set, e.g. increasing the length of treatment that can be tolerated. Not all objectives can be identified within recognised assessment tools in the early stages.”) Some goals might not be easily measurable (“Goals do not have to be measurable as improvement in engagement and motivation can be a goal that will be difficult to quantify.”) Goals should be jargon free. One person indicated the opinion that this was a redundant statement. | ||

| Meaningful and relevant | 92.0 | ||

| Should be focused on activities and participation | 69.7 | ||

| Challenging but achievable Both short and long-term targets | 76.0 | ||

| May involve one MDT team member or may be multidisciplinary | 70.1 | ||

| Involve carer/family where possible, with consent of person who has had a stroke | 76.0 | ||

| Used to guide therapy and treatment | 81.0 | ||

F.5.3.2. Delphi statements where consensus was not achieved

Table 8Table of ‘non-consensus’ statements with qualitative themes of panel comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goals should have predicted dates for completion. | 36.5 | In round 2 – 24/98 (24%) panel members commented; 19/85(22%) in round 3: Themes: Flexibility – timing of goals should not be too rigid and prescriptive. Type of goals – some goals don’t leant themselves to predict an end point Effect on patients – focus on dates and failure can lead to distress and have an impact on confidence and esteem Progression – Rather than giving one date, regular reviews lead to a feeling of progress | |

| A review of goals of the person who has had a stroke should be conducted between the person and the multidisciplinary team member delivering the intervention at the expected date of completion. | 42.4 | In round 2 – 14/99 (14%) panel members commented; 13/85(15%) in round: The panel’s comments have the following themes – some of these are mirroring those for expected dates of goals: Expected date – it was queried whether there would be an expected date (“I don’t agree that goals always need to have an expected date of completion.”) Regular reviews – goals should be regularly reviewed as an ongoing process (“But should be constantly reviewed throughout therapy.”). Flexibility – when and how the review would take place should be flexible (“These people should be involved but there does need to be some flexibility”). Team or individual member - Could involve an individual team member, but sometimes also the whole team (“This should be part of the weekly MDT meeting which the patient should take part in.”). One person objected to this statement since it represents and ideal scenario rather than what can be achieved in clinical practice (“if you did all these things, you’d never have time to do any actual therapy.”). | |

| The reasons for unattained goals and goals that have been reassessed need to be documented. | 56.5 | In round 2 – 11/99 (11%) panel members commented; 6/85(7%) in round 3: Generally this was seen as positive, but it was stated that this may be too reflective for some and that it needs to benefit the individual rather than be a measure of outcome. “It is helpful to know why a goal is not being met – to learn about patterns of recovery and what affects progress.” | |

| Patients should have a written copy of their goals. | 52.4 | In round 3 (this statement was first introduced in round 3) 17/84 (20%) panel members commented There was a feeling that the format of this documentation would not always be accessible to the person who has had a stroke (cognitive or language impaired persons for instance). “It might be helpful if this stated that these goals should be in language appropriate to the patient (not MDT language) and that where possible, they should reflect the patient’s own words in setting the goals.” “For patients with memory problems this is particularly important but also written goals aid communication between the patient, team and family”. |

F.5.4. Care Planning

F.5.4.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 9Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Documentation related to rehabilitation should be individualised, and contain the following minimum information: | 17/99 (17%) panel members commented: A number of additional documents were suggested: Return to work information was mentioned most frequently Information on additional support available after discharge (carer support organisations, stroke support groups etc) Stroke education/lifestyle information | |

| Basic demographics including contact details and next to kin | 93.9 | ||

| Diagnosis and relevant medical information | 96.9 | ||

| List of current medications including allergies | 92.9 | ||

| Standardised screening assessments to include those identified in earlier questions | 78.7 | ||

| Person focused rehabilitation goals | 93.9 | ||

| Multidisciplinary progress notes | 79.5 | ||

| Key contact from the stroke rehabilitation team to co-ordinate health and social care needs | 87.8 | ||

| Discharge planning information | 85.8 | ||

| Joint health/social care plans if developed | 76.5 | ||

| Follow up appointments | 79.5 | ||

| 2. | In the development of rehabilitation plans, efforts should be made to encourage the person who has had a stroke and carers to be involved and actively participate. | 86.9 | 17/99 (17%) panel members commented: This was seen as important in person centred care. It was mentioned that the wishes of the person who has had a stroke should be taken into consideration. Some people find this a stressful experience. Three people expressed an opinion that this was a redundant statement. |

| 3. | Rehabilitation plans should be reviewed by the multidisciplinary team at least once per week. | 71.4 | In round 2 – 41/95 (43%) panel members commented; 34/77(44%) in round 3 The phase of rehabilitation was commented on. Weekly reviews early on in the acute phase, or when the person who has had a stroke is an inpatient, reducing to longer intervals as the rehabilitation progresses. “not sensible. In first 6 weeks weekly is needed there after two weekly is reasonable – or longer” “in light of the quick throughput of hospital stroke patients the review may need to be undertaken twice a week”. There was a concern not to be too prescriptive about timing. “because each person who has had a stroke is different, the review should take place according to needs of the individual and this will vary” Type of plan and type of goal was also seen as important: “This depends on how you define rehabilitation plans. Are they broad, e.g. to go home independently walking and self care and returning to work or more specific to the moment e.g. to be able to stand for 5 minutes in a standing frame?” |

F.5.4.2. Delphi statement where consensus was not reached

Table 10Table of ‘non-consensus’ statements with qualitative themes of panel comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | When there is a significant change, or when a plateau/potential is reached, or before discharge, a meeting involving the stroke rehabilitation team, with an invitation to the person and their family/carer, should be conducted to discuss these points. | 63.4 | In round 2 – 22/99 (22%) panel members commented; 16/85(19%) in round 3 and 11/72 (15%) in round 4: There were several themes: MDT – some members of the panel thought that this does not have to involve the whole team (“The meetings should happen but only include the relevant staff, not the whole stroke rehabilitation team”). Before discharge – this was seen as the most important aspect of the statement. Need for an additional meeting – if there are regular reviews then changes/plateau should not come as a surprise Meeting type – this needs to be tailored (formal or informal) to the individual and their carer/family Statement – the statement itself was seen as having too many different components to answer with one response. Several people commented that the terms ‘plateau’ or ‘potential’ was unclear. (“What is plateau? One day of no change, one week, one month?”) |

F.5.5. Transfer of care, discharge planning and interface with social care

F.5.5.1. Component and consensus protocol

Table 11What planning and support should be undertaken by the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team before a person who had a stroke is discharged from hospital or transfers to another team/setting to ensure a successful transition of care?

| Population | Adults and young people 16 or older who have had a stroke |

|---|---|

| Components |

|

| Outcomes |

|

F.5.6. Transfer of care and discharge planning

F.5.6.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 12Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Each patient should have a documented discharge report which has been discussed with the person who has had a stroke and their carer/s prior to transfer of care, including discharges to residential settings. | 75.5 | 14/98 (14%) panel members commented This was seen as important, but it was questioned whether this would be different to the GP report, a copy of which would be given to the person who has had a stroke. This should be written in an accessible way. | |

| A discharge report (informing ongoing rehabilitation planning) should contain information about the following: | 31/99 (31%) panel members commented A few further suggestions and comments were made: The individual’s named point of contact. Joint health and social care plan. Stroke Association Information Further comments: The terms ‘mental capacity’ was queried – i.e. capacity for what, and whether ‘cognitive status’ may be a better term It was felt not necessary to have all these for all people. | ||

| Diagnosis and health status | 86.8 | ||

| Mental capacity | 69.7 | ||

| Functional abilities | 86.8 | ||

| Transfers and mobility | 82.8 | ||

| Care needs for washing, dressing, toileting and feeding | 82.8 | ||

| Psychological and emotional needs | 77.7 | ||

| Medication needs | 84.8 | ||

| Social circumstances | 76.7 | ||

| Management of risk including the needs of vulnerable adults | 74.7 | ||

| Ongoing goals | 76.5 | ||

| Ways of accessing rehabilitation services | 74.4 | ||

| A home visit (with the person who has had a stroke present) may be required when simulation of the home environment set up in the inpatient setting has been inconclusive or there is an indication for further assessment. | 69.8 | 14/96 (14%) panel members commented A limited number of panel members provided comments for this statement: One person felt that there were limits on staff time and resources Another person stated that this depended on whether an early supported discharge team was available. This could delay discharge from hospital was mentioned. The term ‘may’ was queried. | |

| 4. | Local systems with open communication channels and timely exchange of information should be established to ensure that the person who has had a stroke is able to transfer to their place of residence in a well timed manner. | 71.7 | 10/99 (10%) panel members commented Of the ten people who commented on this statement seven indicated that the phrasing of the statement was confusing and contained jargon. Of the other three, one commented on the role of the key worker, another person commented that this should minimise duplication and administration and the third person stated that this should be done as soon as it is safe to do so. |

| 5. | Local health and social care providers should have established standard operating procedures to ensure a safe discharge process. | 74.0 | 11/100 (11%) panel members commented Individual issues were raised in the comments: Any changes to procedures need to be communicated in timely fashion Take into account person’s wishes and be aware of carer stress and vulnerable adult procedures Ideally joint standard procedures A need for flexibility and broad guidance that can be easily individualised, rather than prescriptive procedures. |

F.5.6.2. Delphi statement where consensus was not reached

Table 13Table of ‘non-consensus’ statements with qualitative themes of panel comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | An access visit (without the person present) can ascertain suitability of access to, from and within the property in respect to the person’s functional, cognitive status and managing risk. | 36.6 | In round 2 – 20/98 (20%) panel members commented; 15/84(18%) in round 3 and 13/71 (18%) in round 4: The majority of comments expressed that the statement was unspecific and did not say whether it should be done or in what circumstances (“The issue is when – always, sometimes, why, how to decide.”). Several people expressed the opinion that this statement was too obvious, since it included the word ‘may’ or later the word ‘can’. |

| 2. | A home visit can ascertain a person’s potential for managing risk and cognitive/functional impairment within a familiar environment. | 56.8 | In round 2 – 11/99 (11%) panel members commented; 13/84(15%) in round 3 and 8/70 (11%) in round 4: The majority of comments expressed that the statement was unspecific and did not say whether it should be done or in what circumstances. (“…guidelines should be given guidance about to whom and under what circumstances a visit - either access or with the patient should be done.” “usually not required if ESD team involved in care”.) Several people expressed the opinion that this statement was too obvious, since it included the word ‘may’ or later the word ‘can’. |

| 3. | Both access and home visits should be coordinated by an occupational therapist and if this is not possible they should have clinical oversight from an occupational therapist. | 19.4 | In round 2 – 38/95 (40%) panel members commented; 34/83(41%) in round 3 and 15/72 (21%) in round 4: The main point of contention was whether or not an OT should oversee this. “although the OT would usually be involved, this does not need to be the case and it may be appropriate for another member of the team to co-ordinate/conduct this depending on what limitations the pt presented with.” |

| 4. | As part of rehabilitation care planning, both access and home visits can be used separately or sequentially, to ascertain suitability for rehabilitation, management of risk and management of life after stroke within the person’s home environment. | 52.1 | In round 2 – 9/99 (9%) panel members commented; 9/83(11%) in round 3 and 11/71 (15%) in round 4: It was felt that this statement was vague and did not define the circumstances of when and how this should happen. There was also a comment that this should not delay discharge and that this is something the community stroke team could undertake. |

F.5.7. Interface with social care

F.5.7.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 14Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Where appropriate, social workers should be involved with the stroke rehabilitation team in the assessment of post hospital care needs. | 72.0 | 11/100 (11%) panel members commented The panel assumed that a social worker would be part of the MDT Some people thought that the term ‘appropriate’ needed to be defined. |

| 2. | The role of social care and any service provision required should be discussed with the person who has had a stroke and documented within the social care plan. | 72.7 | 10/99 (10%) panel members commented A few panel members highlighted the relationship between this statement and the joint care plan and that there should be access to one set of notes. A couple of people thought that this should be discussed fully with the person who has had a stroke and with the carer or nearest relative. In another comment it was stated that it is not necessary to discuss the whole plan with the person who has had a stroke in case the amount of information was overwhelming |

| 3. | When social needs are identified there needs to be timely involvement of social services to ensure seamless transfer from primary to community care. | 76.8 | 11/100 (11%) panel members commented Several panel members commented that a social worker should be part of the MDT. One person commented whether the statement should read ‘from secondary to community care’ rather than ‘from primary to community care’. Another comment was regarding the concepts of ‘timely’ and ‘seamless’ which were not defined and the statement should be set out to describe minimum standards. |

| 4. | Coordination between health and social care should include a timely, accurate assessment (including documentation and communication) to facilitate the transitional process for admission/return to care or nursing homes. | 77.8 | 10/99 (10%) panel members commented This should also include the management staff of the care home. Social worker should be part of the MDT. There would be no need for this since integrated health and social care teams would deal with this. The term ‘timely’ was questioned. |

| 5. | Should family members wish to participate in the care of the person who has had a stroke; they should be offered training in assisting the person who has had a stroke in their activities of daily living prior to discharge. | 79.8 | 18/99 (18%) panel members commented There were some comments about the need for consent from the person who has had a stroke. The difficulty of arranging this prior to discharge was mentioned and whether this could be done at the person’s home was raised. It was also stated that there should not be an assumption that people are willing to provide high levels of care. Respite care and carer support options should also be identified and put in place. |

F.6. Long term health and social support for people after stroke

F.6.1. Component and consensus protocol

Table 15What ongoing health and social support does the person after stroke and their carer(s) require to maximise social participation and long term recovery?

| Population | Adults and young people 16 or older who have had a stroke |

|---|---|

| Components |

|

| Outcomes |

|

F.6.2. Long term health and social support for people after stroke

F.6.2.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 16Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| If there is a new identified need for further stroke rehabilitation services, the person who has had a stroke should be able to self re-refer with the support of a GP or specialist community services. | 66.7 | In round 2 – 23/99 (23%) panel members commented; 11/81(14%) in round 3: One issue that was highlighted is the demand this may create (“Direct self referral could lead to demand outstripping resources of the stroke rehab service. There does need to be an assessment.”). Other panel members thought that the phrase ‘with the support of’ was unclear since this would not mean self-referral anymore. “we operate self referral for anyone previously known to the stoke service”. “ this is unclear, how can you self refer with the support of a GP, are they still being gatekeepers then?” | |

| Focus on life after stroke may include: | In round 2 – 10/98 (10%) panel members commented; 37/85(44%) in round 3 (direct prompt given in round 3): A few other areas of focus were suggested. Return to work / training Relationships, childcare issues Secondary prevention – diet, exercise Psychological / emotional adaptation Stroke groups – communication support activities Support for carers Access to welfare benefits and allowances, equipment | ||

| Information and discussion about community access | 75.2 | ||

| Participation in community activities | 72.9 | ||

| Social roles | 70.2 | ||

| Information about driving | 76.4 | ||

| Opportunities to discuss issues around sexual function | 68.2 | ||

| While the person with stroke is in hospital local processes should ensure that referral is made to adult social care for an assessment of need (if the person has a need for social care). | 67 | In round 2 – 19/99 (19%) panel members commented; 21/84(25%) in round 3: It was highlighted that a social worker should be part of the MDT. “at an appropriate time to allow the social worker to work alongside the MDT to fully appreciate the patient’s difficulties and get to know them and their family. This shouldn’t be started right at the end of the inpatient stay, but ‘worked up’ during the inpatient stay”. Some people commented that this should be a joined up process and happen in a timely manner. “yes, prior to discharge so there is not a long gap between services ending and others beginning”. A couple of people commented that the statement was not very clear (e.g. ‘local processes’ was not defined and also, who would be making the assessment is unclear) | |

F.6.2.2. Delphi statement where consensus was not reached

Table 17Table of ‘non-consensus’ statements with qualitative themes of panel comments

| Number | Statement | Results | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Review intervals need to be specified and agreed with the person who has had a stroke in regards to their long term rehabilitation needs. | 65.0 | In round 2 – 13/100 (13%) panel members commented; 9/80(11%) in round 3: Opinions were divided. Some members suggested that this should be needs based and flexible whereas others said that the 6 and 12 month follow-up was sufficient. |

| 2. | A review of health and social care needs of the person who has had a stroke hat is formally reported and / or coordinated or conducted with the GP services should take place at least (options: 6 months, 12 months, unspecified) | 44.6 | In round 2 – 40/98 (41%) panel members commented; 20/83(24%) in round 3: The majority of comments stated, 6 wks, 6 months and then annually. (“in accordance with the National Stroke Strategy @ 6/52, 6/12 then annually”). There were some comments recommending a need based system that would allow more frequent intervals if necessary. It was also commented that this would depend on the time post discharge. There was a concern that if it were to be a needs based approach people would not be given an opportunity for a meeting unless they have a need “If left to individual needs it tends to result in crises management meetings. There should be some sort of structure and process to ensure that reviews are frequent enough to monitor the patient longer term safely and reasonably but not too frequent to be unnecessary and possibly devaluing the merit…” |

| 3. | Where the persons who have had a stroke are still making progress likely to lead to functional change, they should be offered a goal-focused enabling care package. | 56.9 | In round 3 – 21/84 (25%) panel members commented; 15/72(21%) in round 4: Some people commented that this statement was not very clear and that the term enabling care package was not universally understood. Extract: “I suspect there will be some issues as to how you measure functional change and the word likely should there be a timescale put on this as this caveat would suggest that most patients/clients would fall into this category and services will find this very difficult to deliver…” Some comments were made about the term ‘functional change’ and that the statement was unclear about what it may be referring to. |

| 4. | When a person with stroke leaves hospital, there should be a review of the discharge process with the person who has had a stroke together with their family and carers by a member of the community stroke rehabilitation team. The aim of this review is to ensure that the discharge plan was followed and carried out, that their current status and goals are reviewed, and a continuing rehabilitation plan is devised. | 56.9 | In round 2 – 22/99 (22%) panel members commented; 16/85(19%) in round 3 and 11/72 (15%) in round 4: There were some comments about the amount of reviews that were suggested. This should be done according to need since some people may be discharged and do not wish or need a post discharge meeting. “Will this apply to every stroke patient or only those discharged with a disability – I agree it should be every stroke patient but that would create a huge workload for the community stroke team … I feel that this should be reconsidered and reflect the varied post-stroke needs of patients and their carers.” |

| 5. | Self-management and training needs form part of long term health education for the person after stroke. | 61.1 | In round 2 – 12/98 (12%) panel members commented; 13/84(11%) in round 3 and 9/72 (15%) in round 4: It was stated that there was insufficient evidence to conclude that this works. There is also the issue that it depends on the level of post stroke ability. “in order to support secondary prevention and more independence, education is important.” “self management isn’t just about education, a person may need other interventions to facilitate behaviour change”. |

F.7. Shoulder pain

F.7.1. Component and consensus protocol

Table 18How should people with shoulder pain after stroke be managed to reduce pain?

| Population | Adults and young people 16 or older who have had a stroke and have symptoms of shoulder pain |

|---|---|

| Components |

|

| Outcomes |

|

F.7.1.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 19Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Information should be provided by the healthcare professional on how to prevent pain/trauma to the shoulder. | 77.6 | 7/49 (14%) panel members commented Most panel members who commented on this question queried who to give the information to (patient, carer, other staff) and under which conditions (if there is weakness in the shoulder). It was stated in one comment that there was no information available on this topic. |

| 2. | When managing shoulder pain the following treatments should be considered: | In round 2 – 23/49 (47%) panel members commented; 13/42(31%) in round 3 None of the other treatment options gained consensus the options were:

| |

| • Positioning | 70.7 | ||

| • Analgesics | 64.2 | ||

F.7.1.2. Delphi statement where consensus was not reached

Table 20Table of ‘non-consensus’ statements with qualitative themes of panel comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The person who has had a stroke should be assessed for shoulder pain | 63.6 | In round 2 – 13/48 (27%) panel members commented; 7/42(17%) in round 3 There was a general opinion that this should be easily ascertained and therefore a full assessment is not needed. |

| 2. | There is a need for an algorithm to assess and treat shoulder pain | 31.0 | In round 2 – 23/49 (47%) panel members commented; 13/42(31%) in round 3 Some comments were made that there are algorithms already in existence. Others commented that the evidence for treatments was poor and therefore there is not enough information to create an algorithm. There were also comments that this would be useful. |

F.8. Speech and language therapies

F.8.1. Component and consensus protocol

Table 21What interventions improve communication in people dysphasia, dysarthrophonia and articulatory dyspraxia?

| Population | Adults and young people 16 or older who have had a stroke and who have speech and language impairments |

|---|---|

| Components |

|

| Outcomes |

|

F.8.2. Speech and language therapies for dysphasia, dysarthrophonia and articulatory dyspraxia

F.8.2.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 22Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | For all people with speech and language impairments the Speech and Language Therapist needs to explain and discuss the impairment with the person who has had a stroke/family/carers/treatment team and teach them how to manage the condition. | 78.6 | 3/28 (11%) panel members commented One person commented that this does not need to be carried out by a speech and language therapist as long as it is under the guidance of one. Carer involvement was also highlighted. One person expressed surprise that Communication Support Services were not included in the whole speech and language section. |

| 2. | Early after stroke the person with a speech and language impairment should be facilitated to communicate everyday needs and wishes, and supported to understand and participate in decisions around, for example, medical care, transfer to the community, and housing. This may need alternative and augmentative forms of communication. | 93.1 | 4/29 (14%) panel members commented It was commented that there are interactions with cognition and emotion and therefore input from other MDT members may be needed. It was stated that AAC may be low tech and simple paper and pen or higher tech I-pad apps could be used. One comment was that this depends on the person’s individual assessment, readiness to participate and his/her stated goals. Training for some members of the MDT may also be necessary. |

| 3. | People who have had a stroke and who have persisting speech and language deficits should be assessed for alternative means of communication (gesture, drawing, writing, use of communication aids). | 73.1 | 2/26 (8%) panel members commented One person stated that mixing people with language and those with speech impairments together is not appropriate in this statement. The other person thought that this statement was too obvious to be useful. |

| 4. | The impact of speech and language impairments on life roles e.g. family, leisure, work, etc should be assessed and possible environmental barriers (e.g. signs, attitudes), should be addressed, jointly with the MDT. | 81.5 | 3/27 (11%) panel members commented One person pointed out that this would not happen in the acute stage of rehabilitation. Another person thought that it should also involve family and friends, employers and relevant other agencies A third person indicated that ‘addressed’ was not clear. |

F.8.2.2. Delphi statement where consensus was not reached

Table 23Table of ‘non-consensus’ statements with qualitative themes of panel comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The key aim of speech and language therapy early after stroke should be to minimise the communication impairment. | 55.0 | In round 2 – 17/27 (63%) panel members commented; 11/20(55%) in round 3 Panel members thought that there are many facets to the aims of speech and language therapy that were not captured by this statement. Such as:

“This can be very broadly defined. Minimising the communication impairment is not necessarily just reducing the actual impairment. It may be providing advice and information which enhances understanding and indirectly minimises the problem, it may be using strategies to facilitate communication, it may be providing facilitated emotional support to reduce trauma which can enhance communication.” |

| 2. | The list of approaches that may be used with a patient who is dysphasic: | In round 2 – 20/27 (74%) panel members commented; 11/19(58%) in round 3 Some further approaches were suggested:

It was also highlighted that the statement implies a focus on language impairment rather than focus on the skills and competence of the person who has dysphasia and those in their communicative environment. This panel member suggested the following approaches to do this:

It was highlighted that this would vary from person to person (“The Speech and Language Therapist would make a communication book tailored to the individual rather than alphabet chart and/or talking mats to aid discussion”). | |

| • Picture cards | 36.8 | ||

| • Drawings | 42.1 | ||

| • Sound Boards | 12.5 | ||

| • Writing | 33.3 | ||

| • Phonological sound cueing | 27.7 | ||

| • Modelling words | 22.2 | ||

| • Sentence completion | 33.3 | ||

| • Melodic intonation therapy | 5.8 | ||

| • Neurolinguistic approach | 27.7 | ||

| • Computerised approach | 38.8 | ||

| 3. | The list of approaches that might be used with a patient who is dysarthric: | In round 2 – 12/24 (47%) panel members commented; 14 commented in round 3 (free text prompt) The following approaches were suggested:

| |

| • Oral muscular exercises | 21.7 | ||

| • Monitoring rate of speech production | 34.7 | ||

| • Pausing | 26.0 | ||

| • Alphabet supplementation | 27.2 | ||

| 4. | List of approaches that might be used with a patient who has dysarthrophonia: | In round 2 – 9/23 (39%) panel members commented; 7/17(41%) in round 3 No clear approaches were suggested. It was stated that this depends on the patient’s presentation and severity. It was also highlighted that this is a rare problem and that there is no evidence to support a particular approach. | |

| • Biofeedback | 12.5 | ||

| • Voice amplifier | 11.7 | ||

| • Intense therapy to increase loudness | 0.0 | ||

| 5. | The list of approaches that might be used with a patient who has articulatory dyspraxia: | In round 2 – 16 panel members commented (free text prompt); 8/14(57%) in round 3 No further approaches were suggested and it was highlighted that any approach needs to be evidence based. | |

| • Cognitive linguistic therapy | 20.0 | ||

| • Repetitive drills | 41.6 | ||

| • Auditory input/analysis | 33.3 | ||

| • Automatic speech | 38.4 | ||

| • Singing | 8.3 | ||

| • Phonemic cueing | 16.6 | ||

| • Word imitation | 8.3 | ||

| • Computer programmes | 38.4 | ||

| • Varley approach | 27.2 | ||

| • AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) reading aloud | 18.1 | ||

| • Distraction practice with feedback | 11.1 | ||

| • Phoneme manipulation tasks | 9.0 | ||

| • Segment by Segment approach | 18.1 | ||

| • SWORD (computer software) | 27.2 | ||

| • Prosodic therapy | 25.0 | ||

| 6. | Any patient with severe articulation difficulties (<50% intelligibility) reasonable cognition and language function should be assessed for and provided with alternative or augmentative communication aids. | 61.1 | In round 2 – 3/25 (12%) panel members commented; 3/18(17%) in round 3 It would depend on stage of rehab, success of rehab and prognosis. One person objected to a level (i.e. below 50% intelligibility) being stated (“… as it may be different for each patient and intelligibility may depend on familiarity with the patient. |

F.9. Visual impairments

F.9.1. Component and consensus protocol

Table 24How should people with visual impairments including diplopia be best managed after a stroke?

| Population | Adults and young people 16 or older who have had a stroke |

|---|---|

| Components |

|

| Outcomes |

|

F.9.2. Visual impairments – people with diplopia or other ongoing visual symptoms after stroke

F.9.2.1. Delphi statements where consensus was achieved

Table 25Table of consensus statements, results and comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | People who have persisting double vision after stroke require a formal orthoptic assessment. | 70.8 | 1/24 (4%) panel member commented The person who commented thought that all other forms of visual impairment would also require orthoptic assessment. |

F.9.2.2. Delphi statement where consensus was not reached

Table 26Table of ‘non-consensus’ statements with qualitative themes of panel comments

| Number | Statement | Results % | Amount and content of panel comments – or themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2. | All people who have impaired acuity, double vision or a visual field defect following a stroke require a formal opthalmology assessment. | 23.8 | In round 2 – 7/24 (29%) panel members commented; 7/21(33%) in round 3 It was pointed out that different aspects in the statement require different actions (“Impaired acuity and double vision both require an ophthalmological diagnosis. Visual field defect after stroke is less problematic, and the diagnosis is usually known – in such cases adaptive treatments and education are the priority.”). Other comments also highlighted that this is not always needed. |

| 3. | People who have ongoing visual symptoms after a stroke, should be provided with information on compensatory strategies from: | In round 2 – 6/23 (26%) panel members commented; 9/20 (45%) in round 3 It was highlighted that it depends on availability and on the need (“Occupational Therapists are most likely to advise re rehab and application to daily life whereas orthoptists can advise on vision strategies. Ophthalmology will ax and rx eye problems but perhaps not so much advise on strategies.”). One panel member was involved in the development of web-based therapies that work by inducing compensatory eye movements | |

| • Ophthalmology services | 15.7 | ||

| • Orthoptic services | 50.0 | ||

| • Occupational therapy services | 31.5 | ||

| 4. | People who have had a stroke and have visual impairments should be provided with contact details for the RNIB or Stroke Association for further information on visual impairments after stroke. | 38.1 | In round 2 – 4/23 (17%) panel members commented; 1/21 (5%) in round 3 People who have persisting double vision after stroke require a formal orthoptic assessment. It was pointed out that this should be done if symptoms persist and not given routinely to everybody. |

| 5. | Assessment and information for registering as sight impaired or severely sight impaired should be provided by referral to an ophthalmologist. | 47.6 | In round 2 – 2/24 (8%) panel members commented; 5/21 (24%) in round 3 It was commented that: “All involved in stroke care should realise that only ophthalmologists can sign the certification of visual impairment form.” Others queried whether an orthoptist could also do this. |

F.10. Delphi Methodology Appendix 1: See Process Protocol in Guideline Appendix B

F.11. Delphi Methodology Appendix 2: Appraisal of existing guidelines

F.11.1. Assessment of existing guidelines for consensus statements

For the assessment of guideline quality, we used complete guideline documents including any additional information available, as in Appendices or other supplementary information, on related websites (e.g. evidence table, algorithms or short guides). The evaluation was conducted using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE – by The AGREE Research Trust http://www.agreetrust.org) instrument which is specifically designed for the assessment of practice guidelines. It comprises 23 items divided into 6 domains of guideline quality. These 6 domains are:

- scope and purpose (3 items)

- stakeholder involvement (3 items)

- rigour of development (8 items)

- clarity of presentation(3 items)

- applicability (4 items)

- editorial independence (2 items)

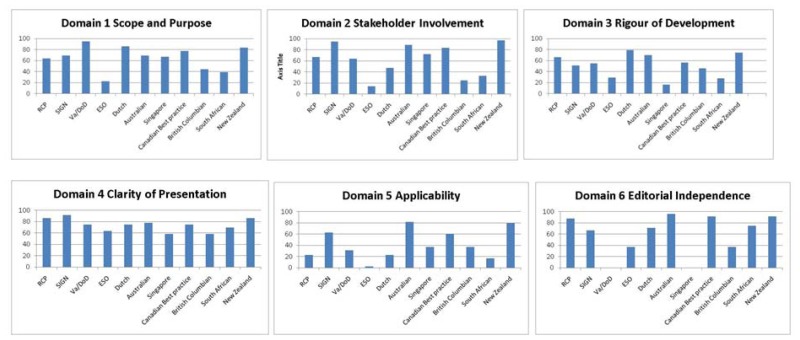

There is an additional overall rating of the quality and a statement of whether the guideline would be recommended for use in practice. Each of the 23 items is rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Results are calculated and reported as the 6 domain scores rather than a total overall and expressed as a percentage across appraisers (in this guideline 2 reviewers appraised all guidelines independently using AGREE). There are no pre-specified cut-offs for domain results in the AGREE instrument. However, the overall assessment features an option of not recommending the guideline for use in practice which would mean that the guideline would be excluded. For domain figures of assessed guidelines please see Figure 1.

F.11.2. AGREE assessment of national and international stroke guidelines

Searches were conducted for guidelines that address the management of stroke (for the search strategy see Appendix D). For details of the scopes of each guideline see Table 27. After assessment with the AGREE-II instrument by two reviewers we included 7 guidelines. AGREE figures are appendicised to this report.

Table 27

Overview of included guidelines.

F.11.3. Overall quality assessment and inter-rater agreement

Two raters assessed the overall quality, the results of which are presented in Table 28. As shown in the table Inter-rater agreement was generally high ranging from the lowest agreement for the Australian guideline (Cronbach’s alpha of .40) to the highest agreement (Cronbach’s alpha of .91) for the Veterans (American) guideline. Domain scores of all assessed guidelines are graphically presented in Figure 1.

F.11.4. Guideline domain profile

Figure 1AGREE-domain scores for both included (RCP, SIGN, Veterans, Dutch, Australian, Canadian Best Practice and New Zealand) and excluded (European (ESO), Singapore, British Columbian and South African)

Scores are given as percentages using both raters’ scores with higher percentage indicating better quality.

F.11.5. Delphi statement drafting process - identfied guideline content mapped to areas in post-consultation

Table 29Areas to address and summary of guideline content plus first draft of statements

| Sections from other guidelines that are relevant to areas need addressing for this guideline | Were sections from other guidelines evidence based or consensus based | Recommendations from other guidelines that were used by the expert consultants to draft the Delphi statements | Statements drafted for the Delphi process |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERVICE DELIVERY RCP - The whole chapter 3 (Systems underlying stroke services): SIGN – chapter 3 (Organisation of services) New Zealand – Chapter 1 (organisation of services) Australian – Chapter 1. Dutch – Chapter 1. Canadian – sections 5.0 Veterans (American) –Chapter 7 | RCP - The majority of the recommendations from chapter 3 are stated as ‘following on from other sections of the guideline’ then there are many by ‘consensus’ and some extrapolations from the NICE guideline, a few others are based on qualitative or (i.e. goal setting) or on studies that do not directly address the stroke population. Recommendations with regards to stroke rehabilitation units were based on Stroke units trialists’ collaboration Cochrane review (2007) SIGN – stroke unit research, case control or cohort studies Australian/New Zealand – mainly from the Stroke units trialists’ collaboration 2007 and Foley N, Salter K, et al. (2007) another meta-analysis of acute, combined and rehabilitation units. Early Supported Discharge (ESD) Trialists. Some lower level evidence and some consensus. Dutch – Stroke unit systematic reviews Canadian – rehabilitation stroke unit – Systematic reviews Veterans – organised multidisciplinary rehab – Stroke units trialists’ collaboration 2007 & systematic reviews | RCP – Rehabilitations should be delivered by a specialist stroke service which could be an inpatient unit, day-hospital unit or at home. It should involve a multidisciplinary team with access to specialist equipment and availability of specialist staff training. SIGN – stroke patients should be admitted to a stroke unit staffed by a multidisciplinary team or in exceptional circumstances (when admission is not possible) admitted to a generic rehabilitation unit. Integrated care pathway is not recommended. Patients and carers should be early actively involved in the process. Australian/New Zealand – early active inpatient rehabilitation by a dedicated stroke team and if ongoing inpatient rehabilitation is required patient should be transferred to a dedicated stroke rehabilitation service. Before discharge all patients should be assessed by a specialist stroke rehab team regarding their suitability for ongoing rehabilitation. Dutch – a hospital stroke unit should be in a stroke service with appropriate rehabilitation facilities Canadian- divides by stroke unit care and all settings. all patients treated in comprehensive or rehabilitation stroke unit. Post acute stroke rehabilitation to be delivered in formally co-ordinated setting Veterans – formally organised & coordinated rehab setting with team experienced in stroke services. if service is not available locally then refer patient to other facility. community rehab for patients mild-moderate disability. inpatient rehab for patients requiring daily prof nursing/multiple interventions required. | Recommendations with regards to the efficacy of stroke rehab units (and whether combined acute/rehab or specific rehab) will come from the update of the Cochrane review on stroke units. |

| MULITIDISCIPLINARY TEAMS RCP – Sections 3.2 recommendation B point 2 and section 3.3 recommendation B SIGN – key recommendation and section 3.3 (membership) and whole chapter 6 New Zealand – section 1.8 Australian – Multidisciplinary team approach in introduction and section 1.2.1. Dutch – section C 1.1 Canadian – sections 5.2 Veterans (American) –Chapter 7.1 | RCP – Stroke units trialists’ collaboration 2007 SIGN – stroke unit research Australian/New Zealand - Stroke units trialists’ collaboration 2007 Dutch – Another earlier systematic review since superseded by SUTC 2007 Canadian – interprofessional specialist rehabilitation teams – Stroke unit trialists collaboration; Veterans – stroke unit trialists, Evans (1995) cifu (1999) SRs | RCP – specifies constituency of a rehab team. SIGN – specifies constituency of a rehab team as well as a description of the roles within such a team. Australian/New Zealand – specifies constituency of rehab team from the outset (i.e. before the review chapters) Dutch – specifies constituency of rehab team. Canadian – specifies the constituency of a rehab team. Veterans- specifies constituency | A core stroke rehabilitation team should comprise of membership from the following disciplines: Consultant neurology/stroke medicine Nursing Physiotherapy Occupational therapy Speech and language therapy Nutrition/Dietetics Clinical/Neuro psychology Social work Pharmacy The stroke rehabilitation team should have a dedicated appropriate professional tasked with coordination and steering of the stroke care pathway. The stroke rehabilitation team should have dedicated rehabilitation assistants. The person who has had a stroke is a member of the stroke rehabilitation team. |