All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Enquiries in this regard should be directed to the British Psychological Society.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Drug Misuse: Opioid Detoxification. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society (UK); 2008. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 52.)

This publication is provided for historical reference only and the information may be out of date.

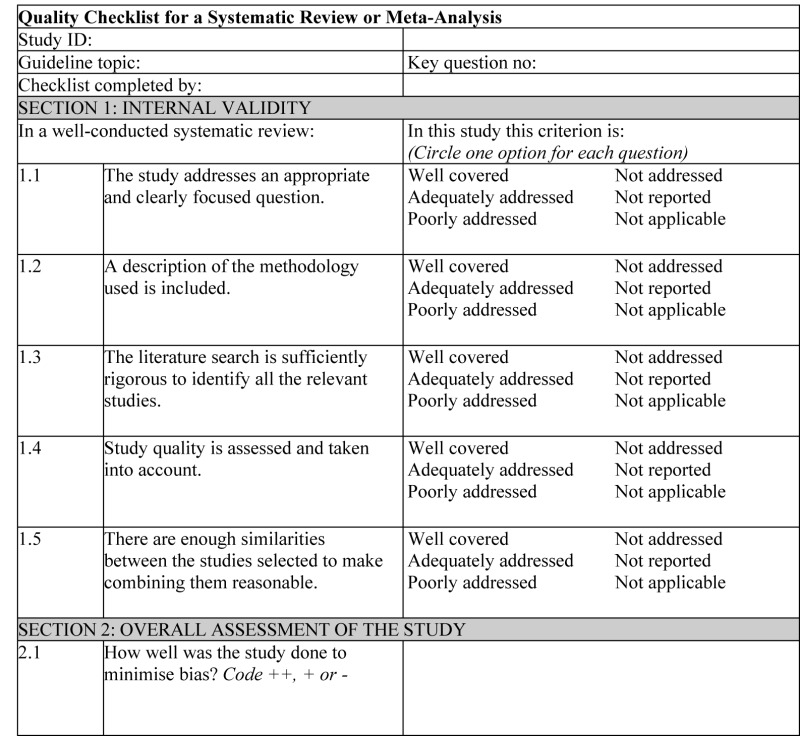

The methodological quality of each study was evaluated using dimensions adapted from SIGN (SIGN, 2002). SIGN originally adapted its quality criteria from checklists developed in Australia (Liddel et al., 1996). Both groups reportedly undertook extensive development and validation procedures when creating their quality criteria.

NOTES ON THE USE OF THE METHODOLOGY CHECKLIST: SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS AND META-ANALYSES

Section 1 identifies the study and asks a series of questions aimed at establishing the internal validity of the study under review – that is, making sure that it has been carried out carefully and that the outcomes are likely to be attributable to the intervention being investigated. Each question covers an aspect of methodology that research has shown makes a significant difference to the conclusions of a study.

For each question in this section, one of the following should be used to indicate how well it has been addressed in the review:

- well covered

- adequately addressed

- poorly addressed

- not addressed (that is, not mentioned or indicates that this aspect of study design was ignored)

- not reported (that is, mentioned but insufficient detail to allow assessment to be made)

- not applicable.

- 1.1.

THE STUDY ADDRESSES AN APPROPRIATE AND CLEARLY FOCUSED QUESTION

Unless a clear and well-defined question is specified in the report of the review, it will be difficult to assess how well it has met its objectives or how relevant it is to the question to be answered on the basis of the conclusions.

- 1.2.

A DESCRIPTION OF THE METHODOLOGY USED IS INCLUDED

One of the key distinctions between a systematic review and a general review is the systematic methodology used. A systematic review should include a detailed description of the methods used to identify and evaluate individual studies. If this description is not present, it is not possible to make a thorough evaluation of the quality of the review, and it should be rejected as a source of level-1 evidence (though it may be useable as level-4 evidence, if no better evidence can be found).

- 1.3.

THE LITERATURE SEARCH IS SUFFICIENTLY RIGOROUS TO IDENTIFY ALL THE RELEVANT STUDIES

A systematic review based on a limited literature search – for example, one limited to MEDLINE only – is likely to be heavily biased. A well-conducted review should at a minimum look at EMBASE and MEDLINE and, from the late 1990s onward, the Cochrane Library. Any indication that hand searching of key journals, or follow-up of reference lists of included studies, were carried out in addition to electronic database searches can normally be taken as evidence of a well-conducted review.

- 1.4.

STUDY QUALITY IS ASSESSED AND TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT

A well-conducted systematic review should have used clear criteria to assess whether individual studies had been well conducted before deciding whether to include or exclude them. If there is no indication of such an assessment, the review should be rejected as a source of level-1 evidence. If details of the assessment are poor, or the methods are considered to be inadequate, the quality of the review should be downgraded. In either case, it may be worthwhile obtaining and evaluating the individual studies as part of the review being conducted for this guideline.

- 1.5.

THERE ARE ENOUGH SIMILARITIES BETWEEN THE STUDIES SELECTED TO MAKE COMBINING THEM REASONABLE

Studies covered by a systematic review should be selected using clear inclusion criteria (see question 1.4 above). These criteria should include, either implicitly or explicitly, the question of whether the selected studies can legitimately be compared. It should be clearly ascertained, for example, that the populations covered by the studies are comparable, that the methods used in the investigations are the same, that the outcome measures are comparable and the variability in effect sizes between studies is not greater than would be expected by chance alone.

Section 2 relates to the overall assessment of the paper. It starts by rating the methodological quality of the study, based on the responses in Section 1 and using the following coding system:

| ++ | All or most of the criteria have been fulfilled. Where they have not been fulfilled, the conclusions of the study or review are thought very unlikely to alter. |

| + | Some of the criteria have been fulfilled. Those criteria that have not been fulfilled or not adequately described are thought unlikely to alter the conclusions. |

| − | Few or no criteria fulfilled. The conclusions of the study are thought likely or very likely to alter. |

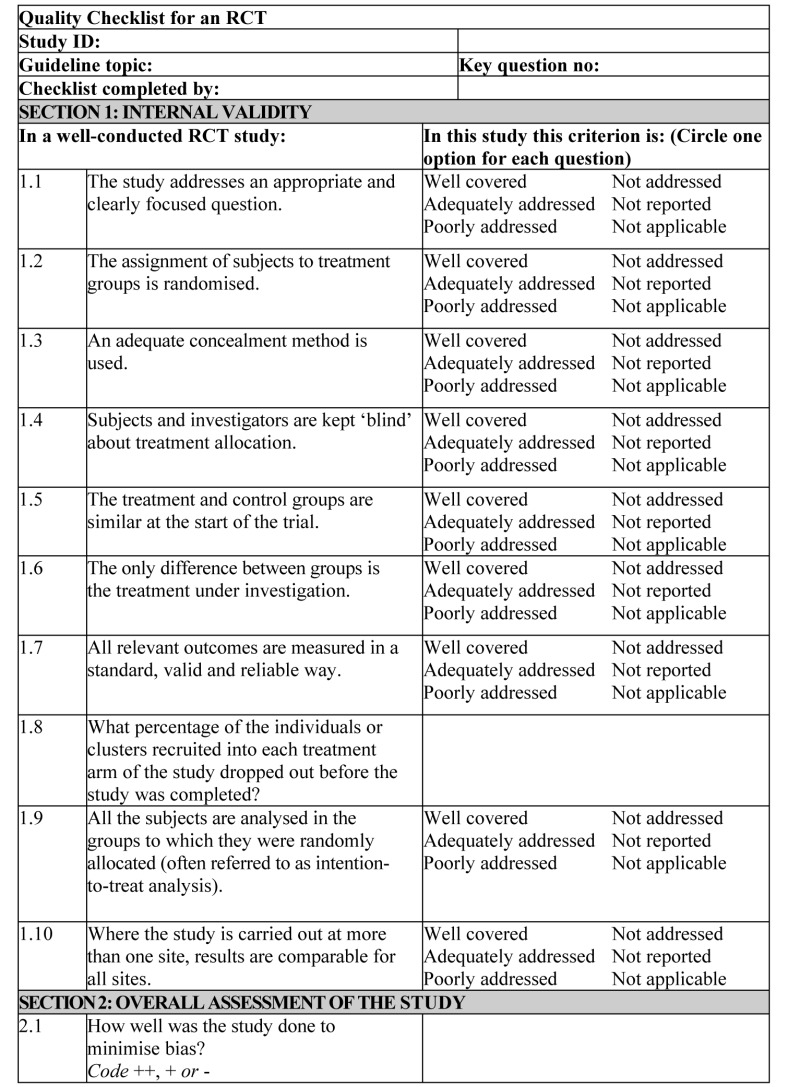

NOTES ON THE USE OF THE METHODOLOGY CHECKLIST: RCTs

Section 1 identifies the study and asks a series of questions aimed at establishing the internal validity of the study under review – that is, making sure that it has been carried out carefully and that the outcomes are likely to be attributable to the intervention being investigated. Each question covers an aspect of methodology that research has shown makes a significant difference to the conclusions of a study.

For each question in this section, one of the following should be used to indicate how well it has been addressed in the review:

- well covered

- adequately addressed

- poorly addressed

- not addressed (that is, not mentioned or indicates that this aspect of study design was ignored)

- not reported (that is, mentioned but insufficient detail to allow assessment to be made)

- not applicable.

- 1.1.

THE STUDY ADDRESSES AN APPROPRIATE AND CLEARLY FOCUSED QUESTION

Unless a clear and well-defined question is specified in the report of the review, it will be difficult to assess how well it has met its objectives or how relevant it is to the question to be answered on the basis of the conclusions.

- 1.2.

THE ASSIGNMENT OF SUBJECTS TO TREATMENT GROUPS IS RANDOMISED

Random allocation of patients to receive one or other of the treatments under investigation, or to receive either treatment or placebo, is fundamental to this type of study. If there is no indication of randomisation, the study should be rejected. If the description of randomisation is poor, or the process used is not truly random (for example, allocation by date or alternating between one group and another) or can otherwise be seen as flawed, the study should be given a lower quality rating.

- 1.3.

AN ADEQUATE CONCEALMENT METHOD IS USED

Research has shown that where allocation concealment is inadequate, investigators can overestimate the effect of interventions by up to 40%. Centralised allocation, computerised allocation systems or the use of coded identical containers would all be regarded as adequate methods of concealment and may be taken as indicators of a well-conducted study. If the method of concealment used is regarded as poor, or relatively easy to subvert, the study must be given a lower quality rating, and can be rejected if the concealment method is seen as inadequate.

- 1.4.

SUBJECTS AND INVESTIGATORS ARE KEPT ‘BLIND’ ABOUT TREATMENT ALLOCATION

Blinding can be carried out up to three levels. In single-blind studies, patients are unaware of which treatment they are receiving; in double-blind studies, the doctor and the patient are unaware of which treatment the patient is receiving; in triple-blind studies, patients, healthcare providers and those conducting the analysis are unaware of which patients received which treatment. The higher the level of blinding, the lower the risk of bias in the study.

- 1.5.

THE TREATMENT AND CONTROL GROUPS ARE SIMILAR AT THE START OF THE TRIAL

Patients selected for inclusion in a trial should be as similar as possible, in order to eliminate any possible bias. The study should report any significant differences in the composition of the study groups in relation to gender mix, age, stage of disease (if appropriate), social background, ethnic origin or comorbid conditions. These factors may be covered by inclusion and exclusion criteria, rather than being reported directly. Failure to address this question, or the use of inappropriate groups, should lead to the study being downgraded.

- 1.6.

THE ONLY DIFFERENCE BETWEEN GROUPS IS THE TREATMENT UNDER INVESTIGATION

If some patients received additional treatment, even if of a minor nature or consisting of advice and counselling rather than a physical intervention, this treatment is a potential confounding factor that may invalidate the results. If groups were not treated equally, the study should be rejected unless no other evidence is available. If the study is used as evidence, it should be treated with caution and given a low quality rating.

- 1.7.

ALL RELEVANT OUTCOMES ARE MEASURED IN A STANDARD, VALID AND RELIABLE WAY

If some significant clinical outcomes have been ignored, or not adequately taken into account, the study should be downgraded. It should also be downgraded if the measures used are regarded as being doubtful in any way or applied inconsistently.

- 1.8.

WHAT PERCENTAGE OF THE INDIVIDUALS OR CLUSTERS RECRUITED INTO EACH TREATMENT ARM OF THE STUDY DROPPED OUT BEFORE THE STUDY WAS COMPLETED?

The number of patients that drop out of a study should give concern if the number is very high. Conventionally, a 20% drop-out rate is regarded as acceptable, but this may vary. Some regard should be paid to why patients dropped out, as well as how many. It should be noted that the drop-out rate may be expected to be higher in studies conducted over a long period of time. A higher drop-out rate will normally lead to downgrading, rather than rejection of a study.

- 1.9.

ALL THE SUBJECTS ARE ANALYSED IN THE GROUPS TO WHICH THEY WERE RANDOMLY ALLOCATED (OFTEN REFERRED TO AS INTENTION-TO-TREAT ANALYSIS)

In practice, it is rarely the case that all patients allocated to the intervention group receive the intervention throughout the trial, or that all those in the comparison group do not. Patients may refuse treatment, or contra-indications arise that lead them to be switched to the other group. If the comparability of groups through randomisation is to be maintained, however, patient outcomes must be analysed according to the group to which they were originally allocated, irrespective of the treatment they actually received. (This is known as intention-to-treat analysis.) If it is clear that analysis was not on an intention-to-treat basis, the study may be rejected. If there is little other evidence available, the study may be included but should be evaluated as if it were a non-randomised cohort study.

- 1.10.

WHERE THE STUDY IS CARRIED OUT AT MORE THAN ONE SITE, RESULTS ARE COMPARABLE FOR ALL SITES

In multi-site studies, confidence in the results should be increased if it can be shown that similar results were obtained at the different participating centres.

Section 2 relates to the overall assessment of the paper. It starts by rating the methodological quality of the study, based on the responses in Section 1 and using the following coding system:

| ++ | All or most of the criteria have been fulfilled. Where they have not been fulfilled, the conclusions of the study or review are thought very unlikely to alter. |

| + | Some of the criteria have been fulfilled. Those criteria that have not been fulfilled or not adequately described are thought unlikely to alter the conclusions. |

| − | Few or no criteria fulfilled. The conclusions of the study are thought likely or very likely to alter. |

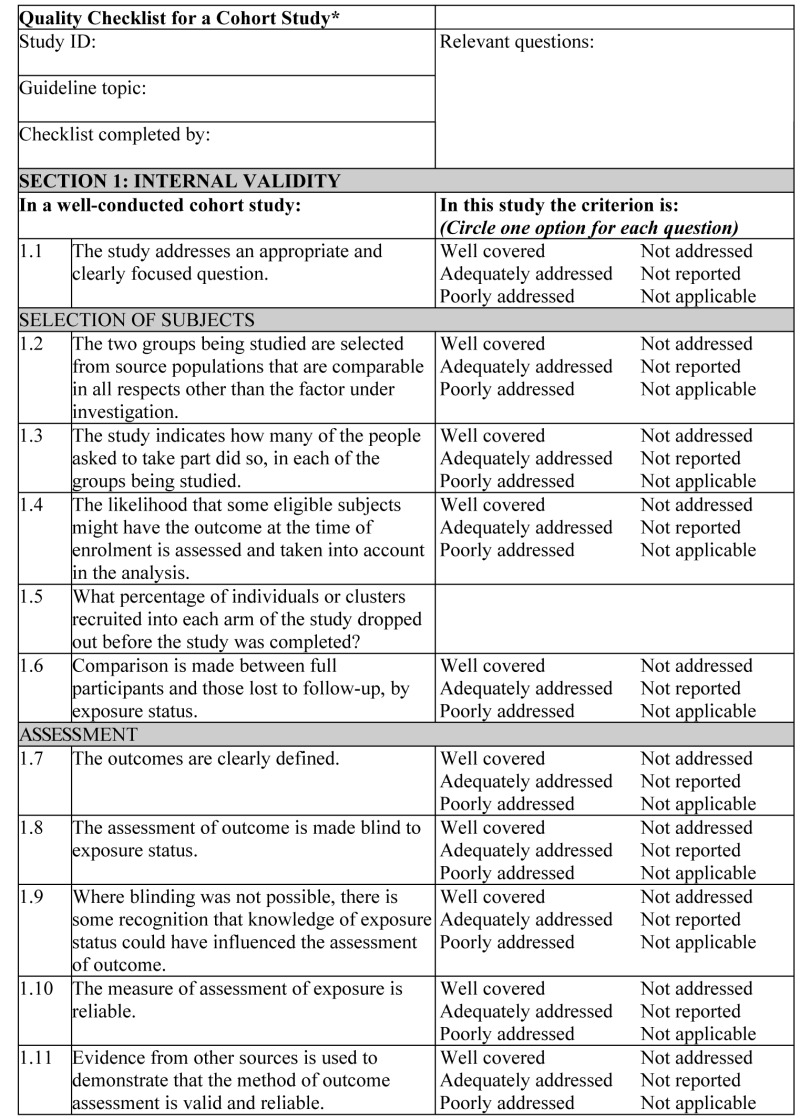

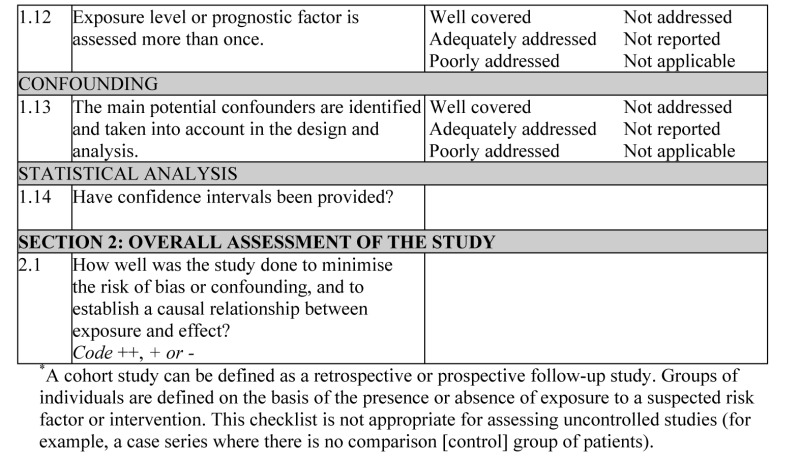

NOTES ON THE USE OF THE METHODOLOGY CHECKLIST: COHORT STUDIES

The studies covered by this checklist are designed to answer questions of the type ‘What are the effects of this exposure?’ It relates to studies that compare a group of people with a particular exposure with another group who either have not had the exposure or have a different level of exposure. Cohort studies may be prospective (where the exposure is defined and subjects selected before outcomes occur) or retrospective (where exposure is assessed after the outcome is known, usually by the examination of medical records). Retrospective studies are generally regarded as a weaker design, and should not receive a 2++ rating.

Section 1 identifies the study and asks a series of questions aimed at establishing the internal validity of the study under review – that is, making sure that it has been carried out carefully, and that the outcomes are likely to be attributable to the intervention being investigated. Each question covers an aspect of methodology that has been shown to make a significant difference to the conclusions of a study.

Because of the potential complexity and subtleties of the design of this type of study, there are comparatively few criteria that automatically rule out use of a study as evidence. It is more a matter of increasing confidence in the likelihood of a causal relationship existing between exposure and outcome by identifying how many aspects of good study design are present and how well they have been tackled. A study that fails to address or report on more than one or two of the questions considered below should almost certainly be rejected.

For each question in this section, one of the following should be used to indicate how well it has been addressed in the review:

- well covered

- adequately addressed

- poorly addressed

- not addressed (that is, not mentioned or indicates that this aspect of study design was ignored)

- not reported (that is, mentioned but insufficient detail to allow assessment to be made)

- not applicable.

- 1.1.

THE STUDY ADDRESSES AN APPROPRIATE AND CLEARLY FOCUSED QUESTION

Unless a clear and well-defined question is specified, it will be difficult to assess how well the study has met its objectives or how relevant it is to the question to be answered on the basis of its conclusions.

- 1.2.

THE TWO GROUPS BEING STUDIED ARE SELECTED FROM SOURCE POPULATIONS THAT ARE COMPARABLE IN ALL RESPECTS OTHER THAN THE FACTOR UNDER INVESTIGATION

Study participants may be selected from the target population (all individuals to which the results of the study could be applied), the source population (a defined subset of the target population from which participants are selected) or from a pool of eligible subjects (a clearly defined and counted group selected from the source population). It is important that the two groups selected for comparison are as similar as possible in all characteristics except for their exposure status or the presence of specific prognostic factors or prognostic markers relevant to the study in question. If the study does not include clear definitions of the source populations and eligibility criteria for participants, it should be rejected.

- 1.3.

THE STUDY INDICATES HOW MANY OF THE PEOPLE ASKED TO TAKE PART DID SO IN EACH OF THE GROUPS BEING STUDIED

This question relates to what is known as the participation rate, defined as the number of study participants divided by the number of eligible subjects. This should be calculated separately for each branch of the study. A large difference in participation rate between the two arms of the study indicates that a significant degree of selection bias may be present, and the study results should be treated with considerable caution.

- 1.4.

THE LIKELIHOOD THAT SOME ELIGIBLE SUBJECTS MIGHT HAVE THE OUTCOME AT THE TIME OF ENROLMENT IS ASSESSED AND TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT IN THE ANALYSIS

If some of the eligible subjects, particularly those in the unexposed group, already have the outcome at the start of the trial, the final result will be biased. A well-conducted study will attempt to estimate the likelihood of this occurring and take it into account in the analysis through the use of sensitivity studies or other methods.

- 1.5.

WHAT PERCENTAGE OF INDIVIDUALS OR CLUSTERS RECRUITED INTO EACH ARM OF THE STUDY DROPPED OUT BEFORE THE STUDY WAS COMPLETED?

The number of patients that drop out of a study should give concern if the number is very high. Conventionally, a 20% drop-out rate is regarded as acceptable, but in observational studies conducted over a lengthy period of time a higher drop-out rate is to be expected. A decision on whether to downgrade or reject a study because of a high drop-out rate is a matter of judgement based on the reasons why people dropped out and whether drop-out rates were comparable in the exposed and unexposed groups. Reporting of efforts to follow up participants that dropped out may be regarded as an indicator of a well-conducted study.

- 1.6.

COMPARISON IS MADE BETWEEN FULL PARTICIPANTS AND THOSE LOST TO FOLLOW-UP BY EXPOSURE STATUS

For valid study results, it is essential that the study participants are truly representative of the source population. It is always possible that participants who dropped out of the study will differ in some significant way from those who remained part of the study throughout. A well-conducted study will attempt to identify any such differences between full and partial participants in both the exposed and unexposed groups. Any indication that differences exist should lead to the study results being treated with caution.

- 1.7.

THE OUTCOMES ARE CLEARLY DEFINED

Once enrolled in the study, participants should be followed until specified end points or outcomes are reached. In a study of the effect of exercise on the death rates from heart disease in middle-aged men, for example, participants might be followed up until death, reaching a predefined age or until completion of the study. If outcomes and the criteria used for measuring them are not clearly defined, the study should be rejected.

- 1.8.

THE ASSESSMENT OF OUTCOME IS MADE BLIND TO EXPOSURE STATUS

If the assessor is blinded to which participants received the exposure, and which did not, the prospects of unbiased results are significantly increased. Studies in which this is done should be rated more highly than those where it is not done or not done adequately.

- 1.9.

WHERE BLINDING WAS NOT POSSIBLE, THERE IS SOME RECOGNITION THAT KNOWLEDGE OF EXPOSURE STATUS COULD HAVE INFLUENCED THE ASSESSMENT OF OUTCOME

Blinding is not possible in many cohort studies. In order to assess the extent of any bias that may be present, it may be helpful to compare process measures used on the participant groups – for example, frequency of observations, who carried out the observations, the degree of detail and completeness of observations. If these process measures are comparable between the groups, the results may be regarded with more confidence.

- 1.10.

THE MEASURE OF ASSESSMENT OF EXPOSURE IS RELIABLE

A well-conducted study should indicate how the degree of exposure or presence of prognostic factors or markers was assessed. Whatever measures are used must be sufficient to establish clearly that participants have or have not received the exposure under investigation and the extent of such exposure, or that they do or do not possess a particular prognostic marker or factor. Clearly described, reliable measures should increase the confidence in the quality of the study.

- 1.11.

EVIDENCE FROM OTHER SOURCES IS USED TO DEMONSTRATE THAT THE METHOD OF OUTCOME ASSESSMENT IS VALID AND RELIABLE

The inclusion of evidence from other sources or previous studies that demonstrate the validity and reliability of the assessment methods used should further increase the confidence in the quality of the study.

- 1.12.

EXPOSURE LEVEL OR PROGNOSTIC FACTOR IS ASSESSED MORE THAN ONCE

Confidence in data quality should be increased if exposure level or the presence of prognostic factors is measured more than once. Independent assessment by more than one investigator is preferable.

- 1.13.

THE MAIN POTENTIAL CONFOUNDERS ARE IDENTIFIED AND TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT IN THE DESIGN AND ANALYSIS

Confounding is the distortion of a link between exposure and outcome by another factor that is associated with both exposure and outcome. The possible presence of confounding factors is one of the principal reasons why observational studies are not more highly rated as a source of evidence. The report of the study should indicate which potential confounders have been considered and how they have been assessed or allowed for in the analysis. Clinical judgement should be applied to consider whether all likely confounders have been considered. If the measures used to address confounding are considered inadequate, the study should be downgraded or rejected, depending on how serious the risk of confounding is considered to be. A study that does not address the possibility of confounding should be rejected.

- 1.14.

HAVE CONFIDENCE INTERVALS BEEN PROVIDED?

Confidence limits are the preferred method for indicating the precision of statistical results and can be used to differentiate between an inconclusive study and a study that shows no effect. Studies that report a single value with no assessment of precision should be treated with caution.

Section 2 relates to the overall assessment of the paper. It starts by rating the methodological quality of the study, based on the responses in Section 1 and using the following coding system:

| ++ | All or most of the criteria have been fulfilled. Where they have not been fulfilled, the conclusions of the study or review are thought very unlikely to alter. |

| + | Some of the criteria have been fulfilled. Those criteria that have not been fulfilled or not adequately described are thought unlikely to alter the conclusions. |

| − | Few or no criteria fulfilled. The conclusions of the study are thought likely or very likely to alter. |

- QUALITY CHECKLISTS FOR CLINICAL STUDIES AND REVIEWS - Drug MisuseQUALITY CHECKLISTS FOR CLINICAL STUDIES AND REVIEWS - Drug Misuse

- CLINICAL STUDY DATA EXTRACTION FORM - Drug MisuseCLINICAL STUDY DATA EXTRACTION FORM - Drug Misuse

- Mus musculus necdin, mRNA (cDNA clone MGC:182402 IMAGE:9056296), complete cdsMus musculus necdin, mRNA (cDNA clone MGC:182402 IMAGE:9056296), complete cdsgi|223461712|gb|BC147249.1|Nucleotide

- PREDICTED: Mus musculus pleckstrin homology domain containing, family A member 5...PREDICTED: Mus musculus pleckstrin homology domain containing, family A member 5 (Plekha5), transcript variant X1, mRNAgi|1907169809|ref|XM_006506863.3|Nucleotide

- Mus musculus solute carrier family 46, member 2 (Slc46a2), mRNAMus musculus solute carrier family 46, member 2 (Slc46a2), mRNAgi|225543516|ref|NM_021053.4|Nucleotide

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...