NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Expectant versus medical management

Review question

How effective is expectant management compared to medical management for tubal ectopic pregnancy?

Introduction

Management of ectopic pregnancy depends upon multiple factors including clinical presentation, haemodynamic stability, ultrasound scan features and serial serum human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) measurements.

Historically, surgical management was offered as the treatment of choice. This remains the case for women with haemodynamic instability, haemoperitoneum or severe pain, or for those with larger ectopic pregnancies (≥35mm), presence of a fetal heart beat or high serum hCG levels (≥5000 IU/L). Currently, women may also be offered medical management, with the use of methotrexate (an antifolate agent) if they are haemodynamically stable with confirmed diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy on ultrasound scan, no significant pelvic pain, no hemoperitoneum, no fetal heart in the ectopic pregnancy, size of ectopic pregnancy < 35mm and hCG level <5000 IU/L.

A third option is expectant management – watchful waiting and monitoring to ensure the ectopic pregnancy resolves without the need for any intervention. The aim of this review is to determine the relative effectiveness of medical and expectant management for women with an ectopic pregnancy.

Summary of the protocol

Please see Table 1 for a summary of the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) characteristics of this review.

Table 1

Summary of the protocol (PICO table).

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Methods and process

This evidence review was developed using the methods and process described in Developing NICE guidelines: the manual 2014. Please see the methods section of the 2012 guideline for further details.

Methods specific to this review question are described in the review protocol in appendix A.

Declarations of interest were recorded according to NICE’s 2018 conflicts of interest policy (see Register of Interests).

Clinical evidence

Included studies

Four randomised controlled trials (n=236) were included in this review (Jurkovic 2017, Korhonen 1996, Silva 2015, van Mello 2012), which compared expectant with medical management with methotrexate. Additional results from the study by van Mello (2012) were identified in a secondary report of the same trial (van Mello 2015) and relevant data were included in the review.

See also the literature search strategy in appendix B and study selection flow chart in appendix C.

Excluded studies

Studies not included in this systematic review with reasons for their exclusion are provided in appendix K.

Summary of clinical studies included in the evidence review

Table 2 provides a brief summary of the included studies.

Table 2

Summary of included studies.

See appendix D for full evidence tables.

Quality assessment of clinical outcomes included in the evidence review

See appendix F for full GRADE tables.

Economic evidence

A systematic review of economic literature was conducted, but no studies were identified which were applicable to this review question.

Economic model

No economic modelling was undertaken for this review.

Evidence statements

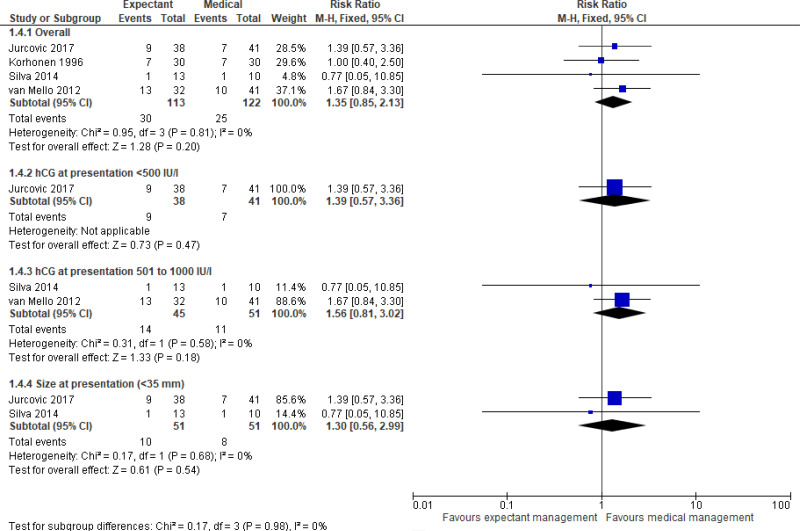

Comparison 1. Expectant versus medical management

Critical outcomes

Resolution of ectopic pregnancy

- Very low quality evidence from four randomised controlled trials (n=236) did not demonstrate any clinically important difference in the resolution of ectopic pregnancy between those who received expectant or medical management. Subgroup analyses (by hCG levels or embryo size at presentation) provided moderate to very low quality evidence which did not detect a clinically significant difference between treatment arms.

Tubal rupture

- Low quality evidence from two randomised controlled trials (n=96) did not demonstrate any clinically important difference in tubal rupture rate between those who received expectant or medical management (no events in either group).

Important outcomes

Need for additional treatment

- Very low quality evidence from four randomised controlled trials (n=236) did not demonstrate any clinically important difference in the need for additional treatment between those who received expectant or medical management. Subgroup analyses (by hCG levels or embryo size at presentation) provided moderate to very low quality evidence which did not detect a clinically significant difference between treatment arms.

Health-related quality of life

- Moderate to low quality evidence from a single randomised controlled trial (n=57) did not demonstrate a clinically important difference in health status (as measured by the short-form 36 [SF-36] and Rotterdam symptom checklist), depression or anxiety (as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) between those who received expectant or medical management.

The committee’s discussion of the evidence

Interpreting the evidence

The outcomes that matter most

The committee identified 3 outcomes of critical importance: maternal mortality, resolution of tubal ectopic pregnancy, and rupture rate. These 3 outcomes were selected as critical since they provide direct evidence about the effectiveness of the interventions in resolving an ectopic pregnancy without leading to adverse events. Additionally, the committee identified the need for additional treatments, future ectopic pregnancy rates, future fertility, and patient satisfaction as important outcomes.

The quality of the evidence

Four randomised controlled trials were included in this review. The quality of the evidence was assessed according to GRADE criteria and ranged from very low to moderate quality evidence. The main reason for downgrading was imprecision – the trials had few participants, and therefore the confidence intervals for the estimates were wide. Some of the trials were also downgraded because of high to very high risk of bias. This was assessed with The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. The main sources of potential bias were: lack of information regarding how the randomisation was performed or concealed; or because women, clinicians and/or outcome assessors were aware of treatment allocation. Two of the trials had not registered their protocol, therefore were downgraded for high risk of reporting bias. There was no evidence available for the outcomes on maternal mortality, future ectopic rates or future fertility rates.

Benefits and harms

The evidence did not show any significant difference between expectant or medical management for ectopic pregnancy resolution, tubal rupture prevention, additional treatment requirements, or health-related quality of life. The committee therefore agreed that expectant management could be offered based on the clinical suitability of a woman, an assessment of the risks and benefits, and the preferences of the woman. The committee agreed that women who were suitable for expectant management were similar to the inclusion criteria in the clinical studies – for example those women who were clinically stable without pain, who had a small ectopic pregnancy, and who had low serum hCG levels (1500 IU/L or lower). Although the inclusion criteria of the four studies permitted women with a range of hCG levels to enter the trials, the committee noted that the majority of participants had relatively low levels of hCG (typically <1000 IU/l). The committee therefore considered that the strongest evidence for the comparison of expectant and medical management was in women with hCG levels <1000 IU/L. Expectant or medical management were both thought to be entirely suitable options to offer these women. The committee considered that expectant management may also be suitable for women with higher hCG levels (up to 1500 IU/L), but there was less evidence to support this. Therefore they made a recommendation that expectant management could be considered for women with hCG levels above 1000 IU/L but below 1500 IU/L.. Similarly, the two studies which reported on the size of the adnexal mass showed that most participants had an adnexal mass of <35mm, therefore this was considered a reasonable threshold to recommend expectant management. All studies in this review excluded women with an ectopic pregnancy with fetal heart activity, therefore the use of expectant or medical management in these women has not been assessed. The committee noted that their clinical experience also supported these thresholds as reasonable for the use of medical or expectant management, and reflected these in the recommendations.

In terms of follow-up care, the committee agreed that serum hCG levels should be carefully monitored regardless of the treatment choice, to ensure they were falling. The committee were aware of a number of studies that had defined a meaningful drop in hCG to be 15% and so they adopted this value. Based on their experience the committee were aware that hCG levels should be checked after 2 days, 4 days and then again at 7 days. If hCG levels plateau or rise, the women should be reviewed by a senior gynaecologist, and a discussion with the woman about other treatment options may be needed.

Based on their clinical expertise, the committee outlined some risks and benefits that should be considered when discussing expectant management with women. The committee outlined that the main benefits of expectant management included a similar rate of resolution of ectopic pregnancy compared to medical management with methotrexate, while avoiding the side effects of methotrexate, such as nausea, anaemia, vomiting or diarrhoea, potentially mild abnormalities in liver and renal function tests, and the need to avoid pregnancy for 3 months. A disadvantage of expectant management is that women may need to be urgently admitted into hospital if their clinical condition worsens, although this may also be the case for women who have received methotrexate.

As there was no evidence available from this review regarding future fertility/pregnancy rates, the committee based the recommendations relating to this on their clinical knowledge and expertise. In addition, there was no evidence relating to the time for resolution of an ectopic pregnancy following medical or expectant management, but the committee were aware that the time was similar in clinical practice and so included this in their recommendations.

The committee noted that healthcare professionals counselling women with an ectopic pregnancy should be sensitive to the woman’s emotions, but did not make a separate recommendation about this as it is already covered in the support and information giving section of the guideline. An ectopic pregnancy can be devastating news and some women experience the same grief as when losing a family member. The committee were also aware that some women consider medical management with methotrexate as a type of abortion and express feelings of guilt. While of course equating treatment of ectopic pregnancy to terminating a pregnancy is not accurate, offering an alternative treatment route of expectant management if clinically appropriate can help such women from an emotional perspective.

Cost effectiveness and resource use

At present there is considerable variation in practice regarding management of ectopic pregnancy. The recommendations may lead to an increase in the use of expectant management for some centres. Moving from medical management to expectant management has the potential to result in cost savings through a reduction in drug use and treatment of associated side effects.

Follow-up will be similar for women choosing expectant or medical management and early pregnancy units may need to admit women as emergencies if either management technique fails. In such cases, surgical intervention is likely to be more costly than it would have been if elective surgical management had been the initial management strategy.

Both expectant and medical management should lead to preservation of future fertility which will result in increased benefits for women, and reduce the downstream financial implications of managing fertility problems.

Other factors the committee took into account

The committee discussed a subgroup analysis conducted by Jurkovic 2017 for women with serum hCG levels between 1000 and 1500 IU/l. The study showed that, on multivariate logistic regression analyses, women with serum hCG levels in this range had an increased “failure rate” (RR 3.6, 95% CI 1.6 to 8), however there were no significant differences between treatment groups (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.6). In light of this, the committee highlighted that for women with higher hCG levels, the success rate of both medical and expectant management is lower.

References

Jurkovic 2017

Jurkovic D, Memtsa M, Sawyer E, Donaldson AN, Jamil A, Schramm K, Sana Y, Otify M, Farahani L, Nunes N, Ambler G. Single-dose systemic methotrexate vs expectant management for treatment of tubal ectopic pregnancy: a placebo-controlled randomized trial. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2017 Feb 1;49(2):171–6. [PubMed: 27731538]Korhonen 1996

Korhonen J, Stenman UH, Ylöstalo P. Low-dose oral methotrexate with expectant management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1996 Nov 1;88(5):775–8. [PubMed: 8885912]Silva 2015

Silva PM, Júnior EA, Cecchino GN, Júnior JE, Camano L. Effectiveness of expectant management versus methotrexate in tubal ectopic pregnancy: a double-blind randomized trial. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2015 Apr 1;291(4):939–43. [PubMed: 25315383]van Mello 2015 (reported as part of van Mello 2012)

van Mello NM, Mol F, Hajenius PJ, Ankum WM, Mol BW, van der Veen F, van Wely M. Randomized comparison of health-related quality of life in women with ectopic pregnancy or pregnancy of unknown location treated with systemic methotrexate or expectant management. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2015 Sep 1;192:1–5. [PubMed: 26125101]van Mello 2012

Van Mello NM, Mol F, Verhoeve HR, Van Wely M, Adriaanse AH, Boss EA, Dijkman AB, Bayram N, Emanuel MH, Friederich J, van der Leeuw-Harmsen L. Methotrexate or expectant management in women with an ectopic pregnancy or pregnancy of unknown location and low serum hCG concentrations? A randomized comparison. Human Reproduction. 2012 Oct 18;28(1):60–7. [PubMed: 23081873]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocols

Table 3. Review protocol for expectant versus medical management

Appendix B. Literature search strategies

Review question search strategies

Appendix C. Clinical evidence study selection

Figure 1. Flow diagram of clinical article selection for expectant versus medical management review

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Table 4. Clinical evidence tables for expectant versus medical management (PDF, 257K)

Appendix E. Forest plots

Comparison 1. Expectant versus medical management

Critical outcomes

Appendix F. GRADE tables

Table 5. Clinical evidence profile: Expectant versus medical management of ectopic pregnancy

Appendix G. Economic evidence study selection

Appendix H. Economic evidence tables

No economic evidence was identified for this review question.

Appendix I. Health economic evidence profiles

No economic evidence was identified for this review question.

Appendix J. Health economic analysis

No health economic analysis was conducted for this review question.

Appendix K. Excluded studies

Economic studies

No economic evidence was identified for this review question.

Appendix L. Research recommendations

No research recommendations were made for this review question.

FINAL

Evidence reviews

developed by the National Guideline Alliance, hosted by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian.

Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties.

NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government, Scottish Government, and Northern Ireland Executive. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn.

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Methotrexate or expectant management in women with an ectopic pregnancy or pregnancy of unknown location and low serum hCG concentrations? A randomized comparison.[Hum Reprod. 2013]Methotrexate or expectant management in women with an ectopic pregnancy or pregnancy of unknown location and low serum hCG concentrations? A randomized comparison.van Mello NM, Mol F, Verhoeve HR, van Wely M, Adriaanse AH, Boss EA, Dijkman AB, Bayram N, Emanuel MH, Friederich J, et al. Hum Reprod. 2013 Jan; 28(1):60-7. Epub 2012 Oct 18.

- Review Methotrexate vs placebo in early tubal ectopic pregnancy: a multi- centre double-blind randomised trial.[Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2012]Review Methotrexate vs placebo in early tubal ectopic pregnancy: a multi- centre double-blind randomised trial.Casikar I, Lu C, Reid S, Bignardi T, Mongelli M, Morris A, Wild R, Condous G. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2012 Aug; 7(3):238-43.

- Efficacy and safety of a clinical protocol for expectant management of selected women diagnosed with a tubal ectopic pregnancy.[Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013]Efficacy and safety of a clinical protocol for expectant management of selected women diagnosed with a tubal ectopic pregnancy.Mavrelos D, Nicks H, Jamil A, Hoo W, Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jul; 42(1):102-7. Epub 2013 May 27.

- Evaluation of maternal serum biomarkers in predicting outcome of successful expectant management of tubal ectopic pregnancies.[Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bi...]Evaluation of maternal serum biomarkers in predicting outcome of successful expectant management of tubal ectopic pregnancies.Memtsa M, Jauniaux E, Gulbis B, Jurkovic D. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020 Jul; 250:61-65. Epub 2020 Apr 30.

- Review Tubal ectopic pregnancy: diagnosis and management.[Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009]Review Tubal ectopic pregnancy: diagnosis and management.Nama V, Manyonda I. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009 Apr; 279(4):443-53. Epub 2008 Jul 30.

- Expectant versus medical management of tubal ectopic pregnancyExpectant versus medical management of tubal ectopic pregnancy

- arf-GAP with Rho-GAP domain, ANK repeat and PH domain-containing protein 2 isofo...arf-GAP with Rho-GAP domain, ANK repeat and PH domain-containing protein 2 isoform X4 [Homo sapiens]gi|2217348777|ref|XP_047305531.1|Protein

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...