NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Pre- and postoperative interventions to optimise outcomes after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair

Review questions

What preoperative interventions are effective in optimising surgical outcome in people undergoing surgical repair of an unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm?

What post-operative interventions are effective in reducing the risk of complications after surgical repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, as well as optimising postoperative outcomes and survival?

Introduction

These review questions aim to determine which interventions can be used preoperatively to ‘optimise’ surgical outcome; and to identify which post-operative interventions are effective in reducing the risk of further aneurysm growth or rupture, cardiovascular events, wound-related complications and graft-related complications (including endoleak, graft migration, graft kinking, incisional hernia, graft occlusion, aortic neck expansion).

PICO tables

Methods and process

This evidence review was developed using the methods and process described in Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. Methods specific to this review question are described in the review protocol in Appendix A.

Declarations of interest were recorded according to NICE’s 2014 conflicts of interest policy.

A ‘bulk’ search strategy was used to cover review questions relating to pre- and postoperative interventions. Two searches were performed to identify studies that assessed the efficacy of interventions that could potentially be used to improve outcomes of surgical repair of AAAs. The first literature search used a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and systematic review (SR) filter while the second search used an observational study filter to identify potentially relevant studies.

The reviewer sifted the RCT database first to identify systematic reviews, RCTs or quasi-randomised controlled trials exploring the efficacy of preoperative interventions for improving outcomes in people who were due to undergo elective surgical repair of unruptured AAAs, or postoperative interventions for improving outcomes in people who underwent elective AAA surgery. Studies were included if they met the set of criteria outlined in Tables 1 and 2 (the full protocol is available in Appendix A). If limited evidence was available from systematic reviews, RCTs or quasi-randomised controlled trials, the observational study database was sifted to identify potentially relevant non-randomised controlled trials.

Table 1

Inclusion criteria for preoperative interventions to optimise outcomes after AAA repair.

Table 2

Inclusion criteria for postoperative interventions to optimise outcomes after AAA repair.

Studies were excluded if they were not:

- were not in English

- were not full reports of the study (for example, published only as an abstract)

- were not peer-reviewed

Clinical evidence

Included studies

Preoperative interventions

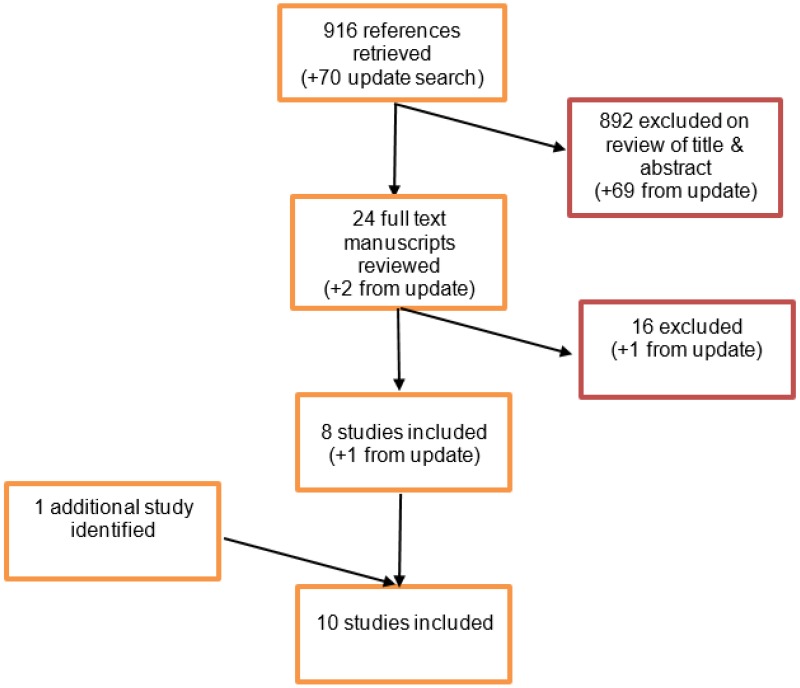

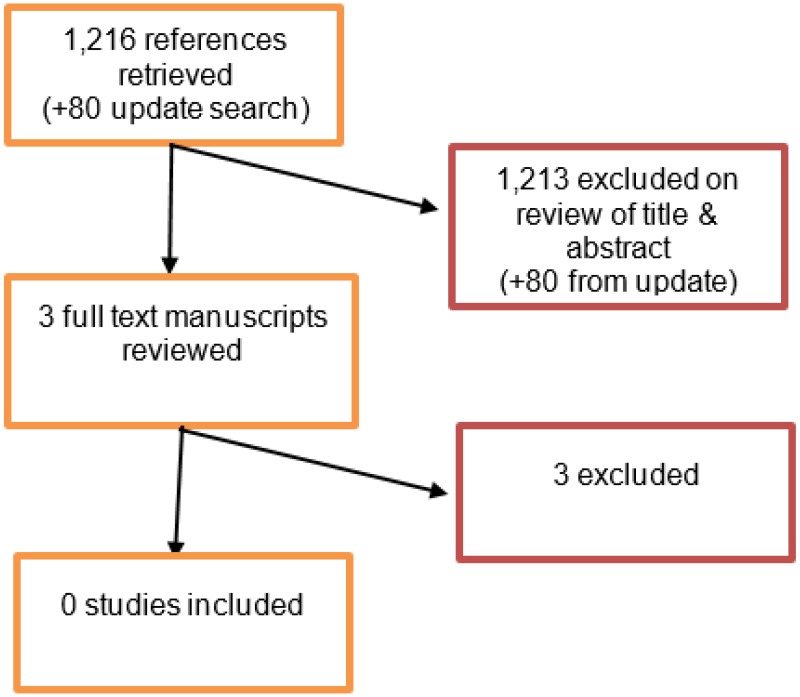

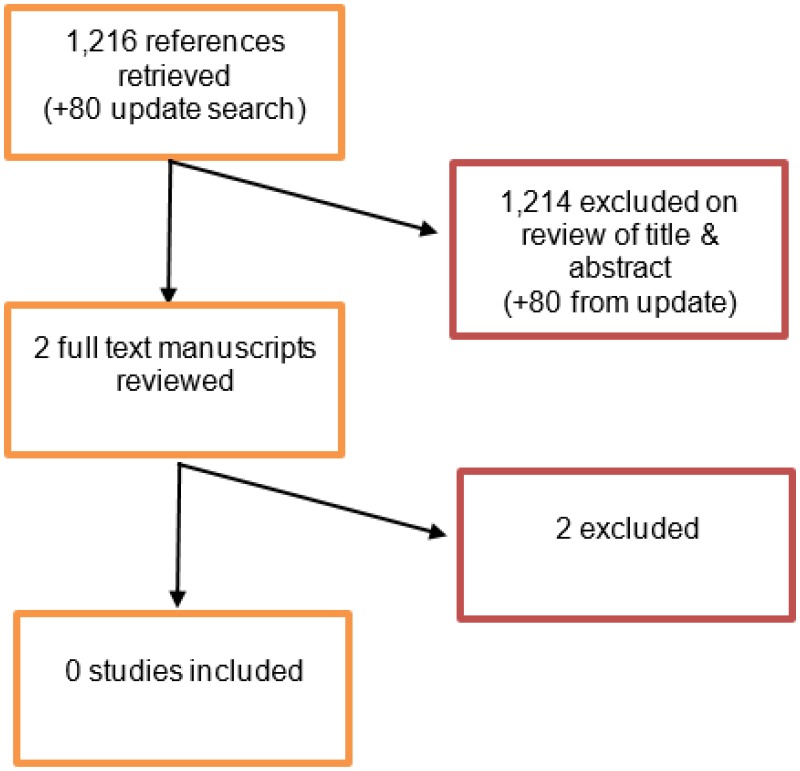

From an initial RCT database of 916 abstracts, 24 were identified as being potentially relevant. Following full-text review of these articles, 8 studies were included. Additionally 1 study was identified via examination of the bibliography of an excluded systematic review. From an initial observational study database of 1,216 abstracts, 3 were identified as being potentially relevant. Following full-text review of these articles, no studies were included.

Update searches were conducted in December 2017, to identify any relevant studies published during guideline development. The update RCT and observational study databases contained 70 and 80 abstracts, respectively. Two abstracts from the RCT database and no abstracts from the observational study were considered potentially relevant. Following full text review of the 2 potentially relevant articles, 1 study was included

Overall, 10 studies were included in the evidence review for this review question.

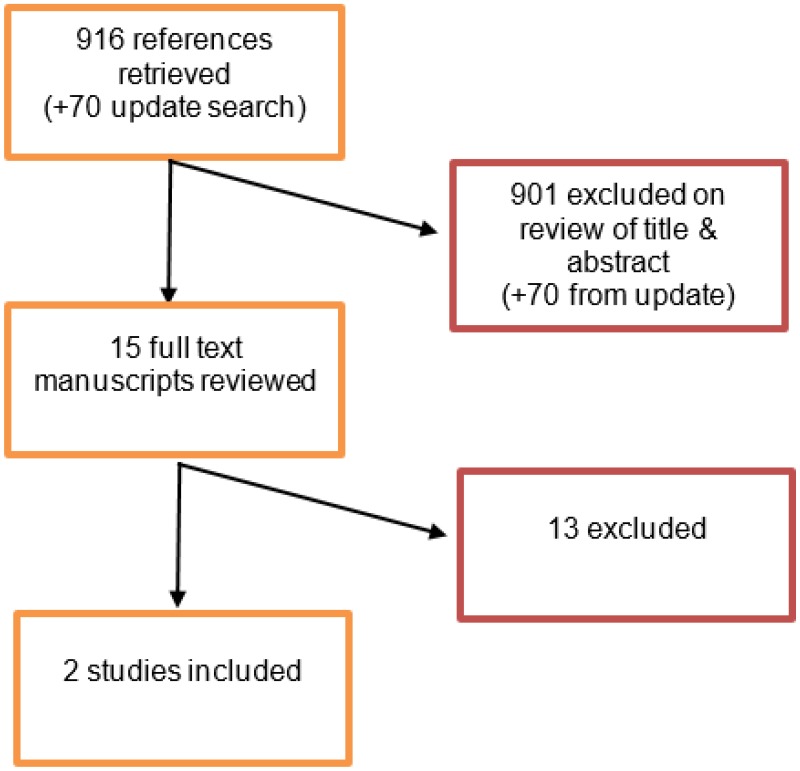

Postoperative interventions

From the RCT database of 916 abstracts, 15 were identified as being potentially relevant. Following full-text review of these articles, 2 studies were included. From the observational study database of 1,216 abstracts, 2 were identified as being potentially relevant. Following full-text review of these articles, no studies were included.

Update searches were conducted in December 2017, to identify any relevant studies published during guideline development. The update RCT and observational study databases contained 70 and 80 abstracts, respectively. No abstracts from either database were considered potentially relevant, and no additional studies were included.

Overall, 2 studies were included in the evidence review for this review question.

Excluded studies

The list of papers excluded at full-text review, with reasons, is given in Appendix H.

Summary of clinical studies included in the evidence review

A summary of the included studies is provided in the tables below.

Preoperative interventions

Table 2

Beta-blockers.

Table 3

Exercise.

Table 4

Remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC).

Postoperative interventions

Table 5

Doxycycline.

Table 6

Physiotherapy plus walking exercises.

See Appendix D for full evidence tables.

Quality assessment of clinical studies included in the evidence review

See Appendix F for full GRADE tables, highlighting the quality of evidence from the included studies.

Economic evidence

Included studies

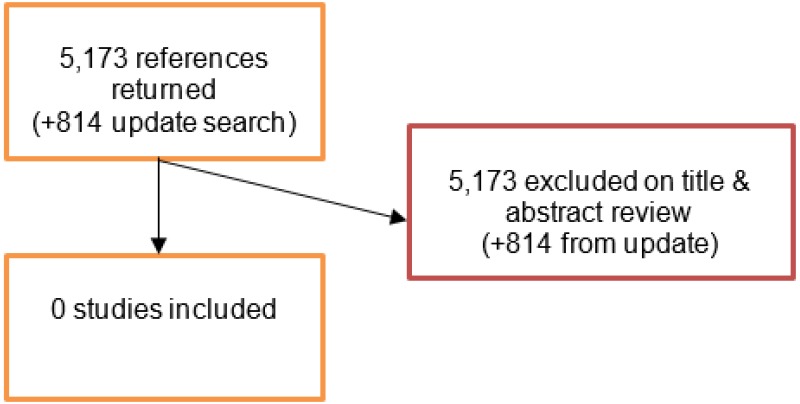

A literature search was conducted jointly for all review questions by applying standard health economic filters to a clinical search for AAA. This search returned a total of 5,173 citations. Following review of all titles and abstracts, no studies were identified as being potentially relevant to these review questions.

An update search was conducted in December 2017, to identify any relevant health economic analyses published during guideline development. The search found 814 abstracts; all of which were not considered relevant to this review. As a result no additional studies were included.

Excluded studies

No studies were retrieved for full-text review.

Evidence statements

Preoperative interventions

Beta-blockers

- Moderate- to high-quality evidence from 1 RCT, including 496 people who underwent elective AAA repair (type not specified), found higher rates of intraoperative hypotension and bradycardia requiring treatment in people who received preoperative beta-blockers compared with those who received placebo.

- Low-quality evidence from 1 RCT, including 496 people who underwent elective AAA repair (type not specified), could not differentiate between rates of cardiac-related mortality, non-cardiac-related mortality, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, postoperative cardiovascular accident, dysrhythmia, new or worsened renal insufficiency, and the need for reoperation in people who received preoperative beta-blockers compared with those who received placebo.

Exercise

- Low-quality evidence from 1 RCT, including 20 people who underwent elective AAA repair (type not specified), could not differentiate between atelectasis rates of people who had been performing inspiratory muscle training during the 2 weeks preceding surgery and those who had not been doing any training.

- Moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT, including 124 people who underwent elective EVAR, indicated that cardiac complications and renal complications were less likely to occur in people who participated in preoperative hospital-based exercise classes compared with those who had not. Low-quality evidence from the same trial could not differentiate between rates of all-cause mortality, pulmonary complications, postoperative bleeding or the need for a blood transfusions of more than 4 units, and the need for reoperation between people who participated in preoperative hospital-based exercise classes and those who did not.

- Low- to moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT, including 53 people who underwent elective EVAR or open surgical repair, could not differentiate preoperative dizziness, preoperative angina, and postoperative quality of life between people who participated in preoperative hospital-based exercise classes and those who did not.

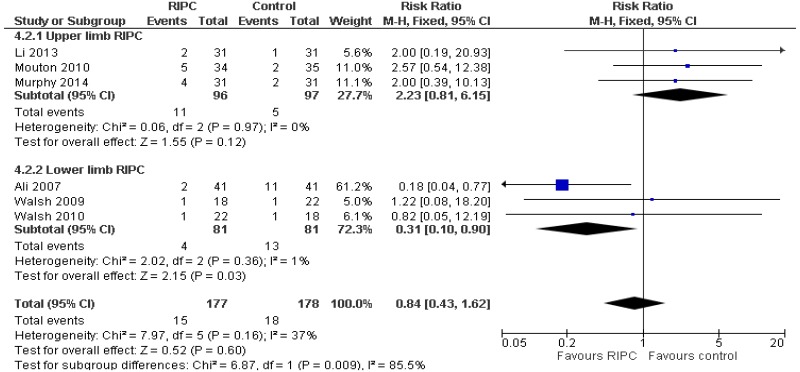

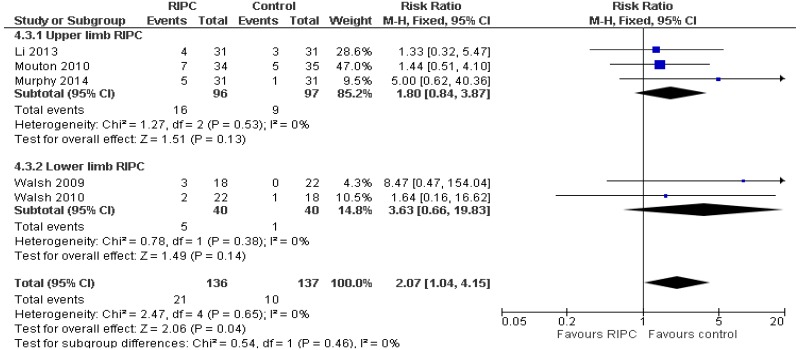

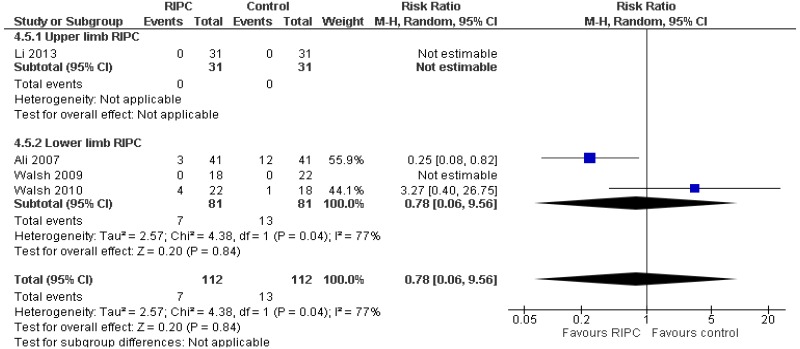

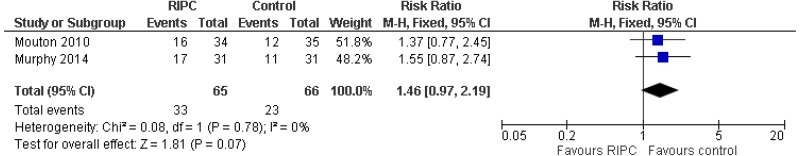

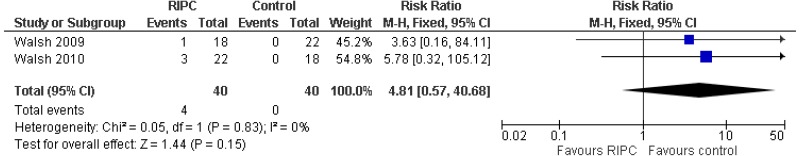

Remote ischaemic preconditioning

- Low-quality evidence from 5 RCTs, including 273 people who underwent elective EVAR or open AAA repair, found higher rates of arrhythmia in people who received remote ischaemic preconditioning before surgery compared with those who received no preconditioning.

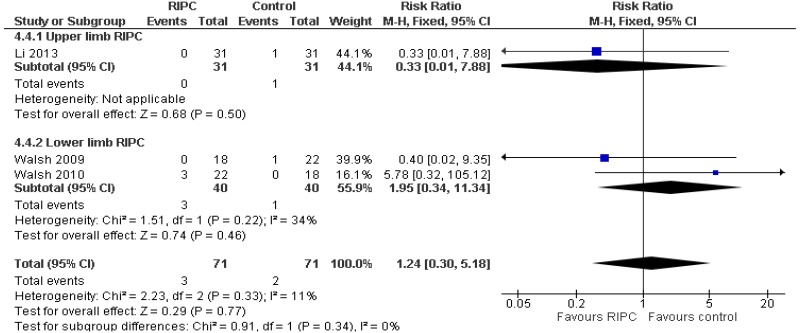

- Very low- to low-quality evidence from up to 6 RCTs, including 355 people who underwent elective EVAR or open AAA repair, could not differentiate rates of 30-day mortality, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, renal impairment or failure, acute kidney injury, and rates of any type of complication between people who did and did not receive remote ischaemic preconditioning.

Postoperative interventions

Doxycycline versus placebo

- Very low-quality evidence from 1 RCT, including 27 people with AAAs who underwent elective EVAR, could not differentiate mean percentage changes in aneurysm diameters between people who received doxycycline after surgery and those who did not.

- Very low-quality evidence from 1 RCT, including 48 people who underwent elective EVAR of AAAs, could not differentiate endoleak and graft migration rates between people who received doxycycline after surgery and those who did not.

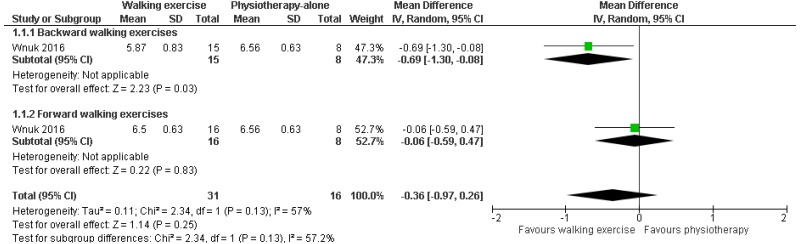

Physiotherapy plus walking exercises versus physiotherapy-alone

- Very low-quality evidence from 1 RCT, including 47 people who underwent elective AAA repair (type not specified) of AAAs, could not differentiate the average length of hospital stay between people who received postoperative physiotherapy plus forward or backward walking exercises and people who received physiotherapy-alone.

Research recommendations

Preoperative interventions

RR4. What is the clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of preoperative exercise programmes for improving outcomes of people who are having AAA repair?

Postoperative interventions

RR5. What are the benefits of postoperative use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACS) for improving outcomes after repair of AAA?

The committee’s discussion of the evidence

Interpreting the evidence

The outcomes that matter most

In relation to preoperative interventions, the outcomes that matter most are perioperative morbidity and mortality. With regards to postoperative interventions, the outcomes which matter most are postoperative morbidity and mortality, and the need for re-intervention.

The quality of the evidence

The committee considered that the identified evidence on preoperative exercise interventions was not robust enough to support a recommendation. Although the identified evidence for most outcomes were graded as being low-to-moderate in quality, the committee felt that the small sample sizes of included studies and relatively short follow-up periods precluded confidence in the reported outcomes. In relation to beta-blockers and RIPC, the committee considered that the evidence was of sufficient quality to draft recommendations.

This review excluded evidence on pre- and postoperative interventions for heterogeneous groups of people with vascular diseases who were treated by different types of surgical and non-surgical interventions, including AAA repair. It was noted that excluded studies did not report what proportions of people received AAA surgery or did not stratify analyses according to type of intervention received. As a result, the committee felt that this type of evidence could not be considered because of uncertain applicability to people with AAA.

The committee noted the existence of specialist society (Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland) guidelines related to AAA repair. It was noted that some of the recommendations in these guidelines relating to preoperative interventions were not based on evidence specific to people with AAA. The committee took these recommendations into account but refrained from cross-referring to specific recommendations.

With respect to postoperative interventions, the committee considered that the identified evidence was limited in both quantity and quality. The two identified studies were graded as very low to low in quality and indicated that postoperative use of doxycycline and physiotherapy plus walking exercises had no impact on the incidence of postoperative complications. As a result, the committee decided not to make any recommendations regarding these interventions.

Benefits and harms

The committee recognised that most people with AAA are likely to be older people with some form of cardiovascular disease. With this in mind the committee believed that optimisation of pre-existing medical conditions and minimisation of cardiovascular risks would increase the general health of people with AAA, leading to reduced postoperative morbidity and mortality. As a result, the committee felt that general principles of secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, as outlined in other NICE guidelines, were applicable. The committee also agreed that it is important to reduce the risks of surgical site infections and venous thromboembolism in all people undergoing AAA repair. As result, recommendations were drafted cross-referring to other NICE guidance.

The committee agreed that the evidence on beta-blockers was clear that de novo beta-blockade in the immediate preoperative period was not effective and was potentially harmful. It was also considered that the evidence on beta-blockers in relation to AAA repair was consistent with broader evidence on the use of beta-blockade in other surgical cohorts, including people undergoing other types of vascular surgery. The committee felt that use of the word “routinely” allowed scope for clinician discretion given that there will be certain indications, for example atrial fibrillation, where beta blockade remains appropriate. It was clear that discontinuation of beta-blockers in such circumstances would be bad practice.

The committee felt that body of evidence on RIPC strongly indicated no benefit to postoperative outcomes, and the potential for harm (arrhythmia). Unlike beta-blockers, the committee felt that there was no particular circumstance where routine use of RIPC should be considered. Thus, a “do not use” recommendation was made.

The committee recognised the risk of thromboembolic events (such as deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) after AAA repair, and noted that no evidence was found relating to the use of postoperative anticoagulation in people who have undergone AAA repair. They noted that Direct-acting Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) have become popular in clinical practice because they are easy to use, have good pharmacokinetic properties associated with fixed dosing, have few interactions with other medications, and require less frequent monitoring. With that in mind, the committee drafted a research recommendation to encourage research on how best to use DOACs in the postoperative period to balance the risk thromboembolic events with that of bleeding.

The committee noted that there is a widespread problem of people with AAA not having their medical therapy optimised, and that it would be good practice for clinicians to optimise medical therapy in all people identified as having an AAA, whether or not they were due to undergo AAA repair. The committee also agreed that it would be good practice for clinicians to perform preoperative medication assessments in order to optimise patient care.

Cost effectiveness and resource use

The committee considered that recommendations relating to secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, prevention and treatment of surgical site infections, and reduction of the risk of venous thromboembolism were unlikely to have an impact on costs and resource use, because they simply cross-refer to existing guidance and reaffirm best clinical practice.

The committee considered the potential costs of treating intraoperative complications of preoperative beta-blockade (hypotension and bradycardia requiring treatment) and believed that a do not use recommendation would prevent such unnecessary expenses from occurring.

Other factors the committee took into account

The committee felt that NHS providers have already started devoting resources to exercise programmes based on a relatively small body of evidence. Thus, there is a role for further research to inform funding decisions. The committee agreed to make their research recommendation purposely broad, to maximise researcher uptake. It was agreed that the research recommendation should not explicitly state the need to monitor “cardiopulmonary” outcomes because there was some concern that researchers would focus on cardiac outcomes, at the expense of respiratory outcomes.

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocols

Review protocol for review question 11: preoperative interventions to optimise outcomes after AAA repair

| Review question 11 | What presurgical interventions are effective in optimising surgical outcome in people undergoing surgical repair of an unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm? |

|---|---|

| Objectives | To determine which interventions can be used preoperatively to ‘optimise’ surgical outcome. |

| Type of review | Intervention |

| Language | English |

| Study design |

Systematic reviews of study designs listed below Randomised controlled trials Quasi-randomised controlled trials If insufficient evidence identified, non-randomised controlled trials |

| Status |

Published papers only (full text) No date restrictions |

| Population | People with a confirmed unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm in whom surgery is planned |

| Intervention |

Statins Beta-blockers Tranexamic acid Antiplatelet therapy Iron supplementation Coronary artery revascularisation Supervised exercise program Ischaemic preconditioning Respiratory training, including incentive spirometry and smoking cessation therapy |

| Comparator | Placebo, no intervention or each other |

| Outcomes |

Mortality Peri- and post-operative complications Adverse effects of intervention Quality of life Resource use, including length of hospital or intensive care stay, and costs |

| Other criteria for inclusion / exclusion of studies |

Exclusion: Non-English language Abstract/non-published Pharmacological interventions not available in the UK |

| Baseline characteristics to be extracted in evidence tables |

Age Sex Size of aneurysm Comorbidities |

| Search strategies | See Appendix B |

| Review strategies |

Appropriate NICE Methodology Checklists, depending on study designs, will be used as a guide to appraise the quality of individual studies. Data on all included studies will be extracted into evidence tables. Where statistically possible, a meta-analytic approach will be used to give an overall summary effect. All key findings from evidence will be presented in GRADE profiles and further summarised in evidence statements. |

| Key papers |

Dronkers, A. Veldman, E. Hoberg, C. van der Waal, N. van Meeteren. Prevention of pulmonary complications after upper abdominal surgery by pre-operative intensive inspiratory muscle training: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil, 22 (2008), pp. 134–142 [PubMed: 18057088] Kothmann, A.M. Batterham, S.J. Owen, A.J. Turley, M. Cheesman, A. Parry, et al. Effect of short-term exercise training on aerobic fitness in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms: a pilot study. Br J Anaesth, 103 (2009), pp. 505–510 [PubMed: 19628486] Myers, 2010. Effects of exercise training in patients with AAA: preliminary reslts from a randomised trial. J Cardiopulm Rehab Prev, 30 (2010), pp. 374–383 [PubMed: 20724934] Tew, 2011. Endurance exercise training in patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysm: a randomised controlled pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 93 (2012), pp. 2148–2153 [PubMed: 22846453] Ali ZA, Callaghan CJ, Lim E, Ali AA, Nouraei SA, Akthar AM, Boyle JR, Varty K, Kharbanda RK, Dutka DP, Gaunt ME. Remote ischemic preconditioning reduces myocardial and renal injury after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: a randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2007 Sep 11;116(11 Suppl):I98–105 [PubMed: 17846333] Mouton R, Pollock J, Soar J, Mitchell DC, Rogers CA. Remote ischaemic preconditioning versus sham procedure for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: an external feasibility randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015 Aug 25;16:377 [PMC free article: PMC4549128] [PubMed: 26303818] Walsh SR, Sadat U, Boyle JR, Tang TY, Lapsley M, Norden AG, Gaunt ME. Remote ischemic preconditioning for renal protection during elective open infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: randomized controlled trial. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2010 Jul;44(5):334–40 [PubMed: 20484066] Walsh SR, Boyle JR, Tang TY, Sadat U, Cooper DG, Lapsley M, Norden AG, Varty K, Hayes PD, Gaunt ME. Remote ischemic preconditioning for renal and cardiac protection during endovascular aneurysm repair: a randomized controlled trial. J Endovasc Ther. 2009 Dec;16(6):680–9 [PubMed: 19995115] |

Review protocol for review question 30: postoperative interventions to optimise outcomes after AAA repair

| Review question 30 | What postoperative interventions are effective in reducing the risk of complications after surgical repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, as well as optimising postoperative outcomes and survival? |

|---|---|

| Objectives | To identify which postoperative interventions are effective in reducing the risk of further aneurysm growth or rupture, CV events, wound-related complications and graft-related complications (including endoleak, graft migration, graft kinking, incisional hernia, graft occlusion, aortic neck expansion). |

| Type of review | Intervention |

| Language | English |

| Study design |

Systematic reviews of study designs listed below Randomised controlled trials Quasi-randomised controlled trials If insufficient evidence identified, non-randomised controlled trials |

| Status |

Published papers only (full text) No date restrictions |

| Population | People who have undergone surgical repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Intervention |

Surgical intervention Antifibrinolytic therapy with tranexamic acid Antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, cilostazol, prasugrel, ticagrelor, or any other antiplatelet drugs) Antihypertensive drugs (calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers (β-blockers; e.g. metoprolol, propranolol), angiotensin-II receptor antagonists, thiazide/ thiazide-like diuretics, or any other antihypertensive drugs) Lipid-lowering therapy (statins (simvastatin, pravastatin, atorvastatin)) Antibiotics (doxycycline, roxithromycin, azithromycin) Diabetic control, including metformin COPD control Smoking cessation Physical therapy/exercise Diet Weight control Control of alcohol consumption |

| Comparator | Placebo, no intervention or each other |

| Outcomes |

Incidence of complications (AAA rupture, AAA growth/expansion, cardiovascular events, wound-related complications, endoleak, graft migration, graft kinking, incisional hernia, graft occlusion, aortic neck expansion) Need for further surgical intervention Mortality (all-cause; AAA-related; cardiovascular; survival) Cardiovascular events Quality of life Adverse effects Resource use and cost |

| Other criteria for inclusion / exclusion of studies |

Exclusion: Non-English language Abstract/non-published Pharmacological interventions not available in the UK |

| Baseline characteristics to be extracted in evidence tables |

Age Sex Size of aneurysm Comorbidities |

| Search strategies | See Appendix B |

| Review strategies |

Appropriate NICE Methodology Checklists, depending on study designs, will be used as a guide to appraise the quality of individual studies. Data on all included studies will be extracted into evidence tables. Where statistically possible, a meta-analytic approach will be used to give an overall summary effect. All key findings from evidence will be presented in GRADE profiles and further summarised in evidence statements. |

| Key papers | Yang H, Raymer K, Butler R, Parlow J, Roberts R. The effects of perioperative beta-blockade: results of the Metoprolol after Vascular Surgery (MaVS) study, a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2006 Nov;152(5):983–90 [PubMed: 17070177] |

Appendix B. Literature search strategies

Clinical search literature search strategy

Main searches

Bibliographic databases searched for the guideline

- Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature - CINAHL (EBSCO)

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews – CDSR (Wiley)

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials – CENTRAL (Wiley)

- Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects – DARE (Wiley)

- Health Technology Assessment Database – HTA (Wiley)

- EMBASE (Ovid)

- MEDLINE (Ovid)

- MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print (Ovid)

- MEDLINE In-Process (Ovid)

Identification of evidence for review questions

The searches were conducted between November 2015 and October 2017 for 31 review questions (RQ). In collaboration with Cochrane, the evidence for several review questions was identified by an update of an existing Cochrane review. Review questions in this category are indicated below. Where review questions had a broader scope, supplement searches were undertaken by NICE.

Searches were re-run in December 2017.

Where appropriate, study design filters (either designed in-house or by McMaster) were used to limit the retrieval to, for example, randomised controlled trials. Details of the study design filters used can be found in section 4.

Search strategy review questions 11 and 30

|

Medline Strategy, searched 16th May 2017 Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to May Week 1 2017 Search Strategy: |

|---|

| 1 Aortic Aneurysm, Abdominal/ |

| 2 Aortic Rupture/ |

| 3 (aneurysm* adj4 (abdom* or thoracoabdom* or thoraco-abdom* or aort* or spontan* or juxtarenal* or juxta-renal* or juxta renal* or paraerenal* or para-renal* or para renal* or suprarenal* or supra renal* or supra-renal* or short neck* or short-neck* or shortneck* or visceral aortic segment*)).tw. |

| 4 (AAA* or RAAA*).tw. |

| 5 or/1-4 |

| 6 Preoperative Care/ or Perioperative Care/ or Perioperative Nursing/ or Postoperative Care/ |

| 7 home care services/ or home care services, hospital-based/ |

| 8 (presurg* or pre-surg* or pre surg* or preop* or pre-op* or pre op or periop* or peri-op* or peri op*).tw. |

| 9 ((perianaesthe* or perianesthe* or surgical) adj4 nursing).tw. |

| 10 ((before or plan* or electiv* or ahead* or prepar* or prior) adj4 (surg* or operat* or procedure* or repair* or care* or outcome*)).tw. |

| 11 (postsurg* or post-surg* or post surg* or postop* or post-op* or post op*).tw. |

| 12 ((after or follow* or electiv* or post*) adj4 (surg* or operat* or procedure* or repair* or care* or outcome*)).tw. |

| 13 (medical* adj4 (therap* or treat* or interven* or manag*)).tw. |

| 14 Elective Surgical Procedures/ |

| 15 Endovascular Procedures/ or Vascular Surgical Procedures/ |

| 16 (endovascular* adj4 aneurysm* adj4 repair*).tw. |

| 17 (endovascular* adj4 aort* adj4 repair*).tw. |

| 18 (upper adj4 abdominal adj4 (repair* or surger* or surgic* or operat* or procedur*)).tw. |

| 19 (EVAR or EVRAR or FEVAR or F-EAVAR or BEVAR or B-EVAR).tw. |

| 20 (Anaconda or Zenith Dynalink or Hemobahn or Luminex* or Memoth-erm or Wallstent).tw. |

| 21 (Viabahn or Nitinol or Hemobahn or Intracoil or Tantalum).tw. |

| 22 or/6-21 |

| 23 exp Antifibrinolytic Agents/ |

| 24 ((antifibrinolytic or anti-fibrinolytic) adj4 (hemostatic or haemostatic or agent*)).tw. |

| 25 ((tranexam* or tranex-am* or tranex am* or tranexan or tranex-and or tranex an) adj4 acid*).tw. |

| 26 TXA.tw. |

| 27 (aminocaproic* adj4 acid*).tw. |

| 28 vitamin k*.tw. |

| 29 (anti plasmin* or anti-plasmin* or (plasmin* adj4 inhibitor*)).tw. |

| 30 Iron/ |

| 31 iron.tw. |

| 32 exp Coronary Artery Bypass/ |

| 33 ((coronary adj4 arter* adj4 bypass*) or (aortocoronary adj4 bypass*)).tw. |

| 34 ((off-pump or off pump) adj4 bypass*).tw. |

| 35 CABG.tw. |

| 36 ((blood-flow or blood flow or perfus*) adj4 restor*).tw. |

| 37 (coronary adj4 (revasculari* or recanali* or reperfus*)).tw. |

| 38 Antibiotic Prophylaxis/ |

| 39 (antibiotic* adj4 (premed* or prophyla*)).tw. |

| 40 (Doxycyclin* or Atridox or Cyclodox or Demix or Doxylar or Efracea or Nordox or Periostat or Ramysis or Vibramycin or Vibramycin).tw. |

| 41 Roxithromycin*.tw. |

| 42 (Azithromycin* or Azyter or Clamelle or Zedbac or Zithromax).tw. |

| 43 Smoking Cessation/ |

| 44 “Tobacco Use Cessation”/ |

| 45 ((cigarette* or smok* or tobacco or nicotine*) adj4 (cessation or withdrawal or ceas*)).tw. |

| 46 ((quit* or stop* or giv* or abstin* or abstain*) adj4 (tobacco or cigarette or smoking or nicotine*)).tw. |

| 47 (smoking adj4 (therap* or rehab*)).tw. |

| 48 (cessation adj4 (treat* or therap* or assist* or advice or advis* or program* or interven* or service*)).tw. |

| 49 Motor Activity/ |

| 50 ((motor or physical* or locomotor or supervis*) adj4 activit*).tw. |

| 51 exp Exercise/ or Exercise Therapy/ |

| 52 (exercise* or exercisi* or kinesiotherap*).tw. |

| 53 exp Physical Fitness/ |

| 54 Physical endurance/ |

| 55 fitness*.tw. |

| 56 (walk* or swim* or jog* or cycl* or bicycl* or bike* or gym*).tw. |

| 57 ((physical* or keep* or cardio* or aerobic or fitness or endurance) adj4 (fit* or activit* or active or train* or therap*)).tw. |

| 58 (aerobic adj4 condition*).tw. |

| 59 Muscle strength/ |

| 60 (muscle adj4 strength*).tw. |

| 61 Ischemic Preconditioning/ |

| 62 ((ischemic* or ischaemic* or remote) adj4 (precondition* or pre-condition* or pre condition*)).tw. |

| 63 (IPC or RIC or RIPC).tw. |

| 64 Respiratory therapy/ |

| 65 exp Breathing Exercises/ |

| 66 ((breath* or respirat* or inhal*) adj4 (exercis* or therap* or train* or alter* or chang* or deepen* or physio* or rehab*)).tw. |

| 67 exp Spirometry/ |

| 68 (spirometr* or bronchospirometr*).tw. |

| 69 exp Diet/ |

| 70 (diet or diets or dieting).tw. |

| 71 (health* adj4 eat*).tw. |

| 72 exp Food/ |

| 73 food*.tw. |

| 74 (weight adj4 (manag* or control* or maintain* or achiev* or goal* or health*)).tw. |

| 75 exp Alcohol-Related Disorders/ |

| 76 (alcohol* adj4 (use* or abus* or drink* or reduc* or intake or consum* or control* or abstain* or abstinen* or depend* or addict* or chonic*)).tw. |

| 77 ((problem* adj4 drink*) or (alcoholic* or alcoholism)).tw. |

| 78 exp Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/ |

| 79 Lung diseases, obstructive/ |

| 80 (COPD* or COAD* or COBD* or AECB*).tw. |

| 81 (chronic adj4 obstruct* adj4 (disease* or airway*)).tw. |

| 82 (chronic* adj4 (airflow* or airway* or bronch* or lung* or respirat* or pulmonary) adj4 obstruct*).tw. |

| 83 exp Diabetes Mellitus/ |

| 84 diabet*.tw. |

| 85 or/23-84 |

| 86 5 and 22 and 85 |

| 87 Aortic Aneurysm, Abdominal/su [Surgery] |

| 88 85 and 87 |

| 89 86 or 88 |

| 90 animals/ not humans/ |

| 91 89 not 90 |

| 92 limit 91 to english language |

Health Economics literature search strategy

Sources searched to identify economic evaluations

- NHS Economic Evaluation Database – NHS EED (Wiley) last updated Dec 2014

- Health Technology Assessment Database – HTA (Wiley) last updated Oct 2016

- Embase (Ovid)

- MEDLINE (Ovid)

- MEDLINE In-Process (Ovid)

Search filters to retrieve economic evaluations and quality of life papers were appended to the population and intervention terms to identify relevant evidence. Searches were not undertaken for qualitative RQs. For social care topic questions additional terms were added. Searches were re-run in September 2017 where the filters were added to the population terms.

Health economics search strategy

| Medline Strategy |

|---|

| Economic evaluations |

| 1 Economics/ |

| 2 exp “Costs and Cost Analysis”/ |

| 3 Economics, Dental/ |

| 4 exp Economics, Hospital/ |

| 5 exp Economics, Medical/ |

| 6 Economics, Nursing/ |

| 7 Economics, Pharmaceutical/ |

| 8 Budgets/ |

| 9 exp Models, Economic/ |

| 10 Markov Chains/ |

| 11 Monte Carlo Method/ |

| 12 Decision Trees/ |

| 13 econom*.tw. |

| 14 cba.tw. |

| 15 cea.tw. |

| 16 cua.tw. |

| 17 markov*.tw. |

| 18 (monte adj carlo).tw. |

| 19 (decision adj3 (tree* or analys*)).tw. |

| 20 (cost or costs or costing* or costly or costed).tw. |

| 21 (price* or pricing*).tw. |

| 22 budget*.tw. |

| 23 expenditure*.tw. |

| 24 (value adj3 (money or monetary)).tw. |

| 25 (pharmacoeconomic* or (pharmaco adj economic*)).tw. |

| 26 or/1-25 |

| Quality of life |

| 1 “Quality of Life”/ |

| 2 quality of life.tw. |

| 3 “Value of Life”/ |

| 4 Quality-Adjusted Life Years/ |

| 5 quality adjusted life.tw. |

| 6 (qaly* or qald* or qale* or qtime*).tw. |

| 7 disability adjusted life.tw. |

| 8 daly*.tw. |

| 9 Health Status Indicators/ |

| 10 (sf36 or sf 36 or short form 36 or shortform 36 or sf thirtysix or sf thirty six or shortform thirtysix or shortform thirty six or short form thirtysix or short form thirty six).tw. |

| 11 (sf6 or sf 6 or short form 6 or shortform 6 or sf six or sfsix or shortform six or short form six).tw. |

| 12 (sf12 or sf 12 or short form 12 or shortform 12 or sf twelve or sftwelve or shortform twelve or short form twelve).tw. |

| 13 (sf16 or sf 16 or short form 16 or shortform 16 or sf sixteen or sfsixteen or shortform sixteen or short form sixteen).tw. |

| 14 (sf20 or sf 20 or short form 20 or shortform 20 or sf twenty or sftwenty or shortform twenty or short form twenty).tw. |

| 15 (euroqol or euro qol or eq5d or eq 5d).tw. |

| 16 (qol or hql or hqol or hrqol).tw. |

| 17 (hye or hyes).tw. |

| 18 health* year* equivalent*.tw. |

| 19 utilit*.tw. |

| 20 (hui or hui1 or hui2 or hui3).tw. |

| 21 disutili*.tw. |

| 22 rosser.tw. |

| 23 quality of wellbeing.tw. |

| 24 quality of well-being.tw. |

| 25 qwb.tw. |

| 26 willingness to pay.tw. |

| 27 standard gamble*.tw. |

| 28 time trade off.tw. |

| 29 time tradeoff.tw. |

| 30 tto.tw. |

| 31 or/1-30 |

Appendix C. Clinical evidence study selection

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Evidence tables for review question 11 (preoperative interventions)

Beta-blockers

Download PDF (169K)

Evidence tables for review question 30 (postoperative interventions)

Doxycycline versus placebo

Download PDF (169K)

Physiotherapy plus walking exercises versus physiotherapy-alone

Download PDF (168K)

Appendix E. Forest plots

Forest plots for review question 11 (preoperative interventions)

Beta-blockers

No meta-analysis was performed.

Exercise

No meta-analysis was performed.

RIPC versus sham RIPC or no RIPC (control)

Appendix F. GRADE tables

Grade tables for review question 11 (preoperative interventions)

Beta-blockers versus placebo

Intraoperative complications

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| Hypotension requiring treatment; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 1.37 (1.10, 1.71) | Moderate |

| Bradycardia requiring treatment; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Not serious | 250 | 246 | RR 2.81 (1.72, 4.61) | High |

- 1

Confidence interval crosses one line of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 1 level.

Postoperative complications

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| Unstable angina; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 3.02 (0.12, 73.88) | Low |

| Myocardial infarction; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 0.91 (0.50, 1.65) | Low |

| Congestive heart failure at 30 days; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 1.68 (0.41, 6.95) | Low |

| Postoperative cerebrovascular accident ; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 1.26 (0.34, 4.64) | Low |

| Dysrhythmia; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 0.71 (0.27, 1.38) | Low |

| New or worsened renal insufficiency; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 1.41 (0.45, 4.39) | Low |

| Need for reoperation; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 1.15 (0.42, 3.13) | Low |

- 1

Confidence interval crosses two lines of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 2 levels.

30-day mortality

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| All-cause mortality; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 0.20 (0.02, 1.69) | Low |

| Cardiac death; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 0.33 (0.01, 8.08) | Low |

| Non-cardiac death; effect sizes below 1 favour beta blockers | |||||||||

| Yang (2006) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 250 | 246 | RR 0.14 (0.01, 2.73) | Low |

- 1

Confidence interval crosses two lines of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 2 levels.

Exercises

Inspiratory muscle training versus no training: postoperative complications

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| Atelectasis; effect sizes below 1 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Dronkers (2008) | RCT | Serious1 | Not serious | N/A | Serious2 | 10 | 10 | RR 0.38 (0.14, 1.02) | Low |

- 1

Very small sample size, downgrade 1 level.

- 2

Confidence interval crosses one line of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 1 level

Physical exercise versus no exercise: preoperative intervention-related adverse events

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| Dizziness; effect sizes below 1 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Tew (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 27 | 26 | RR 2.89 (0.12, 67.69) | Low |

| Angina; effect sizes below 1 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Tew (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 27 | 26 | RR 2.89 (0.12, 67.69) | Low |

- 1

Confidence interval crosses 2 lines of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 2 level

Physical exercise versus no exercise: postoperative complications

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| Cardiac complications (including myocardial infarction, prolonged inotropic support, new onset arrhythmia, and unstable angina); effect sizes below 1 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Barakat (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Serious1 | 62 | 62 | RR 0.36 (0.14, 0.93) | Moderate |

| Pulmonary complications (including pneumonia, pneumonia requiring reintubation, exacerbation of COPD, and reintubation); effect sizes below 1 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Barakat (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious2 | 62 | 62 | RR 0.54 (0.23, 1.26) | Low |

| Renal complications (including acute renal failure and renal insufficiency); effect sizes below 1 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Barakat (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Serious1 | 62 | 62 | RR 0.31 (0.11, 0.89) | Moderate |

| Postoperative bleeding or need for a blood transfusion of more than 4 units; effect sizes below 1 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Barakat (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious2 | 62 | 62 | RR 0.57 (0.18, 1.85) | Low |

| Need for reoperation; effect sizes below 1 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Barakat (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious2 | 62 | 62 | RR 0.67 (0.12, 3.84) | Low |

- 1

Confidence interval crosses one line of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 1 level.

- 2

Confidence interval crosses two lines of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 2 levels.

Physical exercise versus no exercise: 30-day mortality

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| All-cause mortality; effect sizes below 1 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Barakat (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious2 | 62 | 62 | RR 1.10 (0.15, 6.88) | Low |

- 1

Confidence interval crosses two lines of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 2 levels.

Physical exercise versus no exercise: length of stay

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| Median length of stay | |||||||||

| Tew (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Very serious1 | 27 | 26 |

Difference in medians: 1 day (Statistical significance not reported) | Low |

- 1

Level of statistical significance not reported, downgrade 2 levels

Physical exercise versus no exercise: quality of life

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| SF-36 Physical function subscale scores at 12 weeks; effect sizes below 0 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Tew (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Serious1 | 27 | 26 | MD −0.3 (−2.7, 2.1) | Moderate |

| SF-36 mental health subscale scores at 12 weeks; effect sizes below 0 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Tew (2016) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | N/A | Serious1 | 27 | 26 | MD −0.5 (−3.3, 2.3) | Moderate |

- 1

Non-significant result, downgrade 1 level.

RIPC

Postoperative complications

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| Any complications; effect sizes below 1 favour RIPC | |||||||||

| 2 studies | RCT | Serious1 | Not serious | Serious2 | Very serious3 | 40 | 38 | RR 1.41 (0.77, 2.56) | Very low |

| Myocardial infarction; effect sizes below 1 favour RIPC | |||||||||

| 6 studies | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious2,3 | Very serious4 | 177 | 178 | RR 0.84 (0.43, 1.62) | Very low |

| Arrhythmia; effect sizes below 1 favour RIPC | |||||||||

| 5 studies | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Serious2 | Serious5 | 136 | 137 | RR 2.07 (1.04, 4.15) | Low |

| Congestive heart failure; effect sizes below 1 favour RIPC | |||||||||

| 3 studies | RCT | Serious1 | Not serious | Serious2 | Very serious4 | 71 | 71 | RR 1.24 (0.30, 5.18) | Very low |

| Renal impairment or failure; effect sizes below 1 favour RIPC | |||||||||

| 4 studies | RCT | Serious1 | Not serious | Very serious2,6 | Very serious4 | 71 | 71 | RR 0.78 (0.06, 9.56) | Very low |

| Acute kidney injury; effect sizes below 1 favour RIPC | |||||||||

| 2 studies | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Serious2 | Serious5 | 146 | 147 | RR 1.46 (0.97, 2.19) | Low |

- 1

Outcome assessors were not blinded of treatment allocations, downgrade 1 level.

- 2

Different surgical techniques (EVAR or open surgical repair) were used across included studies, downgrade 1 level.

- 3

I2 between 33% and 66.7%, downgrade 1 level.

- 4

Confidence interval crosses two lines of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 2 levels.

- 5

Confidence interval crosses one line of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 1 levels.

- 6

I2 between >66.7%, downgrade 2 levels.

Mortality

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| 30-day mortality; effect sizes below 1 favour RIPC | |||||||||

| 2 studies | RCT | Serious1 | Not serious | Serious2 | Very serious3 | 40 | 40 | RR 4.81 (0.57, 40.68) | Very low |

- 1

Outcome assessors were not blinded of treatment allocations, downgrade 1 level.

- 2

Different surgical techniques (EVAR or open surgical repair) were used across included studies, downgrade 1 level.

- 3

Confidence interval crosses two lines of a defined minimum clinically important difference (RR MIDs of 0.8 and 1.25), downgrade 2 levels.

Grade tables for review question 30 (postoperative interventions)

Doxycycline versus placebo

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| Mean percentage change in aneurysm diameter | |||||||||

| Hackmann (2008) | RCT | Very serious1 | Not serious | N/A | Very serious2 | 12 | 15 |

Non-significant (MD not reported) | Very low |

| Presence of endoleak | |||||||||

| Hackmann (2008) | RCT | Very serious1 | Not serious | N/A | Very serious2 | 20 | 24 |

Non-significant (RR not reported) | Very low |

| Occurrence of graft migration | |||||||||

| Hackmann (2008) | RCT | Very serious1 | Not serious | N/A | Very serious2 | 20 | 24 |

Non-significant (RR not reported) | Very low |

- 1

Patients in the placebo group were significantly older than those in the doxycycline group. A higher proportion of patients in the doxycycline group were smokers. Finally, authors reported some outcome measures for the whole study population whereas other outcome measures were only reported for the intervention group; omitting results for the placebo group. Downgrade 2 levels.

- 2

Risk ratio and measures of dispersion not reported. Downgrade 2 levels.

Physiotherapy plus walking exercises versus physiotherapy-alone

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect estimate | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Intervention | Control | Summary of results | |

| Hospital length of stay (days); effect sizes below 0 favour exercise group | |||||||||

| Wnuk (2016) | RCT | Serious1 | Not serious | Serious2 | Serious3 | 31 | 16 | MD −0.36 (−0.97, 0.26) | Very low |

- 1

Unclear whether intervention arms were similar at the start of the trial. Furthermore, there were moderate levels of losses to follow-up: 17 participants were excluded from the study during the postoperative period due to cardiac complications. Downgrade 1 level.

- 2

I2 value between 33.3% and 66.7%, downgrade 1 level.

- 3

Non-significant result. Downgrade 1 level.

Appendix H. Excluded studies

Clinical studies

Review question 11 (preoperative interventions)

| No. | Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alreja G, Bugano D, and Lotfi A (2012) Effect of remote ischemic preconditioning on myocardial and renal injury: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The Journal of invasive cardiology 24, 42–8 [PubMed: 22294530] | Meta-analysis assessed the efficacy of remote ischaemic preconditioning by pooling data from 3 studies of patients undergoing AAA repair and 2 studies of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. No subgroup or sensitivity analysis was performed. |

| 2 | Bani-Hani M, Titi M A, Jaradat I, and al-Khaffaf H (2008) Interventions for preventing venous thromboembolism following abdominal aortic surgery (Cochrane review) [with consumer summary]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, andIssue 1 , [PMC free article: PMC9006878] [PubMed: 18254082] | The systematic review included studies of patients who underwent aortic surgery not related to AAAs: aortic bifurcation graft surgery and aortic reconstruction surgery. |

| 3 | Chello M, Mastroroberto P, Romano R et al. (1996) Protection by coenzyme Q10 of tissue reperfusion injury during abdominal aortic cross-clamping. The Journal of cardiovascular surgery 37, 229–35 [PubMed: 8698756] | Intervention (antioxidant supplement) is not outlined in the review protocol. |

| 4 | Desai M, Gurusamy K, Ghanbari H et al. (2011) Remote ischaemic preconditioning does not improve morbidity or mortality following open or endovascular aneurysm repair: A meta-analysis. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery 12, S139 | Conference abstract. |

| 5 | Kertai M D, Boersma E, Westerhout C et al. (2004) A combination of statins and beta-blockers is independently associated with a reduction in the incidence of perioperative mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 28, 343–52 [PubMed: 15350554] | Not a controlled trial. The study is a retrospective study which assessed the perioperative outcomes of patients with AAAs that had been taking statins and compared with those who had not been taking statins. |

| 6 | Kothmann E, Batterham A M, Owen S J et al. (2009) Effect of short-term exercise training on aerobic fitness in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms: a pilot study. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2009 Oct, and 103(4):505–510 , [PubMed: 19628486] | Participants in this study did not go on to receive surgery. As a result, this study does not assess whether exercise training is effective in optimising surgical outcomes in people undergoing surgical repair. |

| 7 | Hayashi K, Hirashiki A, Kodama A et al. (2016) Impact of preoperative regular physical activity on postoperative course after open abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. Heart and vessels 31, 578–83 [PubMed: 25666952] | Not a controlled trial. This is a prospective cohort study which assessed whether patients preoperative physical activity levels affected postoperative outcomes of people undergoing AAA surgery. |

| 8 | Holzheimer R G (2003) Oral antibiotic prophylaxis can influence the inflammatory response in aortic aneurysm repair: results of a randomized clinical study. Journal of chemotherapy (Florence, and Italy) 15, 157–64 [PubMed: 12797394] | Outcome measure not of interest. Study assesses how oral antibiotic administration affects circulating inflammatory markers. No definitive outcomes were assessed. |

| 9 | Lo Sapio, P , Chechi T, Gensini GF et al. (2014) Impact of two different cardiac work-up strategies in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. International journal of cardiology 175, e1–e3 [PubMed: 24856806] | Study is not directly relevant to this review question. This is a non-randomised comparative study comparing 2 algorithms for preoperative work-up: no comparisons were made with a control group (standard care). |

| 10 | McElrath M, Myers J, Chan K, et al. (2017) Exercise adherence in the elderly: Experience with abdominal aortic aneurysm simple treatment and prevention. Journal of vascular nursing : official publication of the Society for Peripheral Vascular Nursing 35(1), 12–20 [PubMed: 28224946] | Participants in this study did not go on to receive surgery. As a result, this study does not assess whether exercise training is effective in optimising surgical outcomes in people undergoing surgical repair. |

| 11 | Mouton R, Pollock J, Soar J et al. (2014) Remote ischaemic preconditioning for elective abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair: a randomized controlled trial to assess feasibility. Applied cardiopulmonary pathophysiology 18, 35 | Conference abstract. |

| 12 | Myers JN, White JJ, Narasimhan B et al. (2010) Effects of exercise training in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm: preliminary results from a randomized trial. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and prevention 30, 374–83 [PubMed: 20724934] | Participants in this study did not go on to receive surgery. As a result, this study does not assess whether exercise training is effective in optimising surgical outcomes in people undergoing surgical repair. |

| 13 | Myers J, McElrath M, Jaffe A et al. (2014) A randomized trial of exercise training in abdominal aortic aneurysm disease. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 46, 2–9 [PubMed: 23793234] | Participants in this study did not go on to receive surgery. As a result, this study does not assess whether exercise training is effective in optimising surgical outcomes in people undergoing surgical repair. |

| 14 | Pouwels S, Willigendael EM, van Sambeek M R H et al. (2015) Beneficial Effects of Pre-operative Exercise Therapy in Patients with an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: A Systematic Review. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 49, 66–76 [PubMed: 25457300] | No quantitative synthesis was performed. Instead authors discussed the results of individual studies. Identified studies were assessed to ascertain their relevance to this NICE review question. |

| 15 | Railton CJ, Wolpin J, Lam-McCulloch J et al. (2010) Renin-angiotensin blockade is associated with increased mortality after vascular surgery. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d’anesthesie 57, 736–44 [PubMed: 20524103] | Not a controlled trial. The study is a cohort study which assessed outcomes of patients with preoperative renin-angiotensin system blockade, achieved either by angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocking agents. |

| 16 | Richardson K, Sanders G, Hayden P et al. (2014) The effect of preoperative exercise on postoperative outcome in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) patients: Pilot study. Intensive care medicine 40, S136 | Conference abstract. |

| 17 | Robertson L, Atallah E, and Stansby G (2017) Pharmacological treatment of vascular risk factors for reducing mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [PMC free article: PMC6464734] [PubMed: 28079254] | Systematic review included one RCT which is already considered in this NICE review. |

| 18 | Tew G A, Moss J, Crank H et al. (2012) Endurance exercise training in patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysm: a randomised controlled pilot study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2012 Dec, and 93(12):2148–2153 , [PubMed: 22846453] | Participants in this study did not go on to receive surgery. As a result, this study does not assess whether exercise training is effective in optimising surgical outcomes in people undergoing surgical repair. |

| 19 | Wijnen M, Vader HL, Van Den Wall Bake, A et al. (2002) Can renal dysfunction after infra-renal aortic aneurysm repair be modified by multi-antioxidant supplementation?. The Journal of cardiovascular surgery 43, 483–8 [PubMed: 12124559] | Intervention (antioxidant supplements) is not outlined in the review protocol. |

| 20 | Wijnen M, Roumen R, Vader HL, et al. (2002) A multiantioxidant supplementation reduces damage from ischaemia reperfusion in patients after lower torso ischaemia. A randomised trial. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 23, 486–90 [PubMed: 12093062] | Intervention (antioxidant supplements) is not outlined in the review protocol. |

Review question 30 (postoperative interventions)

| No. | Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abdul-Hussien H, Hanemaaijer R, Verheijen JH et al. (2009) Doxycycline therapy for abdominal aneurysm: Improved proteolytic balance through reduced neutrophil content. Journal of vascular surgery 49, 741–9 [PubMed: 19268776] | Outcome measure not of interest. Study assesses how doxycycline affects aortic wall expression of the enzyme, matrix metalloproteinase. |

| 2 | Aoki A, Suezawa T, Yamamoto S et al. (2014) Effect of antifibrinolytic therapy with tranexamic acid on abdominal aortic aneurysm shrinkage after endovascular repair. Journal of vascular surgery 59, 1203–8 [PubMed: 24440679] | Not a controlled trial. The study involved a retrospective review of medical records of patients treated before and after 5 institutions started administering tranexamic acid as part of their EVAR treatment protocols. |

| 3 | Boker A, Haberman CJ, Girling L et al. (2004) Variable ventilation improves perioperative lung function in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysmectomy. Anesthesiology 100, 608–16 [PubMed: 15108976] | Perioperative intervention: study assessed the efficacy of variable ventilation delivered during surgery. |

| 4 | Brinkmann S J. H, Buijs N, Vermeulen M A et al. (2016) Perioperative glutamine supplementation restores disturbed renal arginine synthesis after open aortic surgery: A randomized controlled clinical trial. American Journal of Physiology - Renal Physiology 311, F567–f575 [PubMed: 27194717] | Outcome measure not of interest. Study assesses how perioperative glutamine administration affects arginine biosynthesis. |

| 5 | de Bruin JL, Baas AF, Heymans MW et al. (2014) Statin therapy is associated with improved survival after endovascular and open aneurysm repair. Journal of vascular surgery 59, 39–44.e1 [PubMed: 24144736] | Post-hoc analysis of an RCT comparing EVAR and open aneurysm repair. One of the secondary outcomes assessed was whether statin therapy reduced the risk of cardiovascular deaths. Unfortunately, it was not clear whether patients received statins before or after surgery. |

| 6 | Duffy MJ, O’Kane CM, Stevenson M et al. (2015) A randomized clinical trial of ascorbic acid in open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental 3, [PMC free article: PMC4486645] [PubMed: 26215814] | Perioperative intervention: study assessed the efficacy of parenteral ascorbic acid, administered during surgery. |

| 7 | Jones CI, Payne DA, Hayes PD et al.(2008) The antithrombotic effect of dextran-40 in man is due to enhanced fibrinolysis in vivo. Journal of vascular surgery 48, 715–22 [PubMed: 18572351] | Perioperative intervention: study assessed the efficacy of dextran-40, administered over 1 hour during surgery. |

| 8 | Kalimeris K, Nikolakopoulos N, Riga M et al. (2014) Mannitol and renal dysfunction after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair procedures: a randomized trial. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia 28, 954–9 [PubMed: 24332919] | Perioperative intervention: study assessed the efficacy of mannitol, administered within 15 minutes of surgery commencement. |

| 9 | Kertai MD, Boersma E, Westerhout CM et al. (2004) Association between long-term statin use and mortality after successful abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. The American journal of medicine 116, 96–103 [PubMed: 14715323] | Not a controlled trial. The study is a retrospective study which assessed the outcomes of patients with AAAs that had been taking statins and compared with those who had not been taking statins. |

| 10 | Leijdekkers VJ, Vahl AC, Mackaay A J et al. (2006) Aprotinin does not diminish blood loss in elective operations for infrarenal abdominal aneurysms: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Annals of Vascular Surgery 20, 322–329 [PubMed: 16779513] | Perioperative intervention: study assessed the efficacy of aprotinin, administered during surgery. |

| 11 | Nicholson ML, Baker DM, Hopkinson BR et al. (1996) Randomized controlled trial of the effect of mannitol on renal reperfusion injury during aortic aneurysm surgery. The British journal of surgery 83, 1230–3 [PubMed: 8983613] | Perioperative intervention: study assessed the efficacy of mannitol, administered during surgery. |

| 12 | Rittoo D, Gosling P, Burnley S et al. (2004) Randomized study comparing the effects of hydroxyethyl starch solution with Gelofusine on pulmonary function in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. British journal of anaesthesia 92, 61–6 [PubMed: 14665554] | Perioperative intervention: study compared the efficacy hydroxyethyl starch solution with gelofusine, administered during surgery. |

| 13 | Smaka TJ, Cobas M, Velazquez OC et al. (2011) Perioperative management of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: update 2010. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia 25, 166–76 [PubMed: 21093297] | Literature review. |

| 14 | Tisi PV, and Shearman CP (1997) Randomized controlled trial of the effect of mannitol on renal reperfusion injury during aortic aneurysm surgery. The British journal of surgery 84, 587 [PubMed: 9112940] | Letter to editor. |

| 15 | West MA, Parry M, Asher R et al. (2015) The Effect of beta-blockade on objectively measured physical fitness in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms-A blinded interventional study. British journal of anaesthesia 114, 878–85 [PubMed: 25716221] | Study did not assess postoperative outcomes. |

Economic studies

No full text papers were retrieved. All studies were excluded at review of titles and abstracts.

Appendix I. Research recommendations

Preoperative exercise programmes

| Research recommendation | What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of preoperative exercise programmes for improving outcomes of people who are having repair of an AAA? |

|---|---|

| Population | People with a confirmed unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm in whom surgery is planned. |

| Intervention(s) | Exercise programmes incorporating physical exercise, preoperative physiotherapy or respiratory muscle training. |

| Comparator(s) | Each other, or no exercise |

| Outcomes |

|

| Study design | Randomised controlled trial |

| Potential criterion | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Importance to patients, service users or the population | NHS providers have started devoting resources to exercise programmes, based on a relatively small body of evidence. Further research on the effectiveness of these programmes is needed to inform funding decisions. |

| Relevance to NICE guidance | Medium priority: no recommendations were made in this guideline due to limited evidence, and further research would allow for recommendations to be possible in future guideline updates. |

| Current evidence base | There is a growing body of evidence on preoperative exercise interventions for people undergoing various types of surgical procedures; however, the evidence relating to people with AAA was limited in quantity. Identified studies evaluating preoperative exercise interventions, in people with AAAs, were not considered robust enough to draft recommendations. The study evaluating the efficacy of inspiratory muscle training, by Dronkers et al. (2008), was considered low in quality as it had a small sample size (20 participants) and a short follow-up period. The study assessing the efficacy on supervised exercise, by Barakat et al (2016) was considered moderate in quality; however, reporting of composite outcomes, made it difficult to establish specific benefits (or harms) associated with the intervention. |

| Equality | No specific equality concerns are relevant to this research recommendation. |

| Feasibility | Postoperative growth and rupture is very rare, such that the committee suggested that it would require a very large RCT to detect an effect. |

Postoperative use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs)

| Research recommendation | What are the benefits of postoperative use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACS) for improving outcomes after repair of AAA? |

|---|---|

| Population | People who have undergone surgical repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. |

| Intervention(s) |

|

| Comparator(s) |

|

| Outcomes |

|

| Study design | Randomised controlled trial |

| Potential criterion | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Importance to patients, service users or the population | The committee recognised the risk of thromboembolic events (such as deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) following AAA surgery, and noted that postoperative anticoagulation, with or without the use of mechanical devices, can safely reduce the risk of such complications. DOACs are becoming increasingly popular because they are easy to use, have good pharmacokinetic properties associated with fixed dosing, have few interactions with other medications, and require less frequent monitoring. With that in mind, it is important to establish how best to use DOACs in the postoperative period to balance the risk thromboembolic events with that of bleeding. |

| Relevance to NICE guidance | Medium priority: no recommendations were made in this guideline due to the lack of evidence, and studies would allow for recommendations to be possible in future guideline updates. |

| Current evidence base | No studies were identified that specifically assessed the efficacy of postoperative use of DOACs for improving outcomes after repair of AAA. |

| Equality | No specific equality concerns are relevant to this research recommendation. |

| Feasibility | Postoperative growth and rupture is very rare, such that the committee suggested that it would require a very large RCT to detect an effect. |

Appendix J. Glossary

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA)

A localised bulge in the abdominal aorta (the major blood vessel that supplies blood to the lower half of the body including the abdomen, pelvis and lower limbs) caused by weakening of the aortic wall. It is defined as an aortic diameter greater than 3 cm or a diameter more than 50% larger than the normal width of a healthy aorta. The clinical relevance of AAA is that the condition may lead to a life-threatening rupture of the affected artery. Abdominal aortic aneurysms are generally characterised by their shape, size and cause:

- Infrarenal AAA: an aneurysm located in the lower segment of the abdominal aorta below the kidneys.

- Juxtarenal AAA: a type of infrarenal aneurysm that extends to, and sometimes, includes the lower margin of renal artery origins.

- Suprarenal AAA: an aneurysm involving the aorta below the diaphragm and above the renal arteries involving some or all of the visceral aortic segment and hence the origins of the renal, superior mesenteric, and celiac arteries, it may extend down to the aortic bifurcation.

- Abdominal compartment syndrome

Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs when the pressure within the abdominal cavity increases above 20 mm Hg (intra-abdominal hypertension). In the context of a ruptured AAA this is due to the mass effect of a volume of blood within or behind the abdominal cavity. The increased abdominal pressure reduces blood flow to abdominal organs and impairs pulmonary, cardiovascular, renal, and gastro-intestinal function. This can cause multiple organ dysfunction and eventually lead to death.

- Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET, sometimes also called CPX testing) is a non-invasive approach used to assess how the body performs before and during exercise. During CPET, the patient performs exercise on a stationary bicycle while breathing through a mouthpiece. Each breath is measured to assess the performance of the lungs and cardiovascular system. A heart tracing device (Electrocardiogram) will also record the hearts electrical activity before, during and after exercise.

- Device migration

Migration can occur after device implantation when there is any movement or displacement of a stent-graft from its original position relative to the aorta or renal arteries. The risk of migration increases with time and can result in the loss of device fixation. Device migration may not need further treatment but should be monitored as it can lead to complications such as aneurysm rupture or endoleak.

- Endoleak

An endoleak is the persistence of blood flow outside an endovascular stent - graft but within the aneurysm sac in which the graft is placed.

- Type I – Perigraft (at the proximal or distal seal zones): This form of endoleak is caused by blood flowing into the aneurysm because of an incomplete or ineffective seal at either end of an endograft. The blood flow creates pressure within the sac and significantly increases the risk of sac enlargement and rupture. As a result, Type I endoleaks typically require urgent attention.

- Type II – Retrograde or collateral (mesenteric, lumbar, renal accessory): These endoleaks are the most common type of endoleak. They occur when blood bleeds into the sac from small side branches of the aorta. They are generally considered benign because they are usually at low pressure and tend to resolve spontaneously over time without any need for intervention. Treatment of the endoleak is indicated if the aneurysm sac continues to expand.

- Type III – Midgraft (fabric tear, graft dislocation, graft disintegration): These endoleaks occur when blood flows into the aneurysm sac through defects in the endograft (such as graft fractures, misaligned graft joints and holes in the graft fabric). Similarly to Type I endoleak, a Type III endoleak results in systemic blood pressure within the aneurysm sac that increases the risk of rupture. Therefore, Type III endoleaks typically require urgent attention.

- Type IV– Graft porosity: These endoleaks often occur soon after AAA repair and are associated with the porosity of certain graft materials. They are caused by blood flowing through the graft fabric into the aneurysm sac. They do not usually require treatment and tend to resolve within a few days of graft placement.

- Type V – Endotension: A Type V endoleak is a phenomenon in which there is continued sac expansion without radiographic evidence of a leak site. It is a poorly understood abnormality. One theory that it is caused by pulsation of the graft wall, with transmission of the pulse wave through the aneurysm sac to the native aneurysm wall. Alternatively it may be due to intermittent leaks which are not apparent at imaging. It can be difficult to identify and treat any cause.

- Endovascular aneurysm repair

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is a technique that involves placing a stent –graft prosthesis within an aneurysm. The stent-graft is inserted through a small incision in the femoral artery in the groin, then delivered to the site of the aneurysm using catheters and guidewires and placed in position under X-ray guidance.

- Conventional EVAR refers to placement of an endovascular stent graft in an AAA where the anatomy of the aneurysm is such that the ‘instructions for use’ of that particular device are adhered to. Instructions for use define tolerances for AAA anatomy that the device manufacturer considers appropriate for that device. Common limitations on AAA anatomy are infrarenal neck length (usually >10mm), diameter (usually ≤30mm) and neck angle relative to the main body of the AAA

- Complex EVAR refers to a number of endovascular strategies that have been developed to address the challenges of aortic proximal neck fixation associated with complicated aneurysm anatomies like those seen in juxtarenal and suprarenal AAAs. These strategies include using conventional infrarenal aortic stent grafts outside their ‘instructions for use’, using physician-modified endografts, utilisation of customised fenestrated endografts, and employing snorkel or chimney approaches with parallel covered stents.

- Goal directed therapy

Goal directed therapy refers to a method of fluid administration that relies on minimally invasive cardiac output monitoring to tailor fluid administration to a maximal cardiac output or other reliable markers of cardiac function such as stroke volume variation or pulse pressure variation.

- Post processing technique

For the purpose of this review, a post-processing technique refers to a software package that is used to augment imaging obtained from CT scans, (which are conventionally presented as axial images), to provide additional 2- or 3-dimensional imaging and data relating to an aneurysm’s, size, position and anatomy.

- Permissive hypotension

Permissive hypotension (also known as hypotensive resuscitation and restrictive volume resuscitation) is a method of fluid administration commonly used in people with haemorrhage after trauma. The basic principle of the technique is to maintain haemostasis (the stopping of blood flow) by keeping a person’s blood pressure within a lower than normal range. In theory, a lower blood pressure means that blood loss will be slower, and more easily controlled by the pressure of internal self-tamponade and clot formation.

- Remote ischemic preconditioning

Remote ischemic preconditioning is a procedure that aims to reduce damage (ischaemic injury) that may occur from a restriction in the blood supply to tissues during surgery. The technique aims to trigger the body’s natural protective functions. It is sometimes performed before surgery and involves repeated, temporary cessation of blood flow to a limb to create ischemia (lack of oxygen and glucose) in the tissue. In theory, this “conditioning” activates physiological pathways that render the heart muscle resistant to subsequent prolonged periods of ischaemia.

- Tranexamic acid

Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic agent (medication that promotes blood clotting) that can be used to prevent, stop or reduce unwanted bleeding. It is often used to reduce the need for blood transfusion in adults having surgery, in trauma and in massive obstetric haemorrhage.

Final

Methods, evidence and recommendations

This evidence review was developed by the NICE Guideline Updates Team

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian.