NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Managing complications after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair

Review question

How should the following complications be managed if they do arise?

- Endoleak (type II in particular)

- Expanding aneurysm sac

- Stent fractures and occlusions

- Graft infection

- Graft migration

- Aortoenteric fistula

- Aortic rupture

- Ischaemic complications (limb, visceral and renal)

Introduction

The aim of this review question was to determine the most effective approach to managing endoleak, expanding aneurysm sac, stent fractures and occlusions, graft infection, graft migration, aortoenteric fistula, aortic rupture, and ischaemic complications (limb, visceral and renal) after abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair.

PICO

Methods and process

This evidence review was developed using the methods and process described in Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. Methods specific to this review question are described in the review protocol in Appendix A.

Declarations of interest were recorded according to NICE’s 2014 conflicts of interest policy.

Two literature searches were performed to identify studies assessing the effectiveness of various approaches of managing complications that may arise after EVAR; including, endoleak, expanding aneurysm sac, stent fractures, occlusions, graft infection, graft migration, aortoenteric fistula, aortic rupture, and ischaemic complications. The first literature search used a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and systematic review (SR) filter while the second search used an observational study filter to identify potentially relevant studies. The databases were sifted to identify all studies that met the criteria detailed in Table 1. The full review protocol can be found in Appendix A.

Table 1

Included studies.

The reviewer sifted the RCT database to identify evidence from RCTs, quasi-randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews of the aforementioned study designs that met the inclusion criteria. If limited evidence was identified, the observational study database was sifted to identify non-randomised controlled trials and prospective cohort studies recruiting a population of 500 or more people who had one of the complications of interest.

Studies were excluded if they were:

- Case-control or cross-sectional studies

- Not in English

- Not full reports of the study (for example, published only as an abstract)

- Not peer-reviewed.

Clinical evidence

Included studies

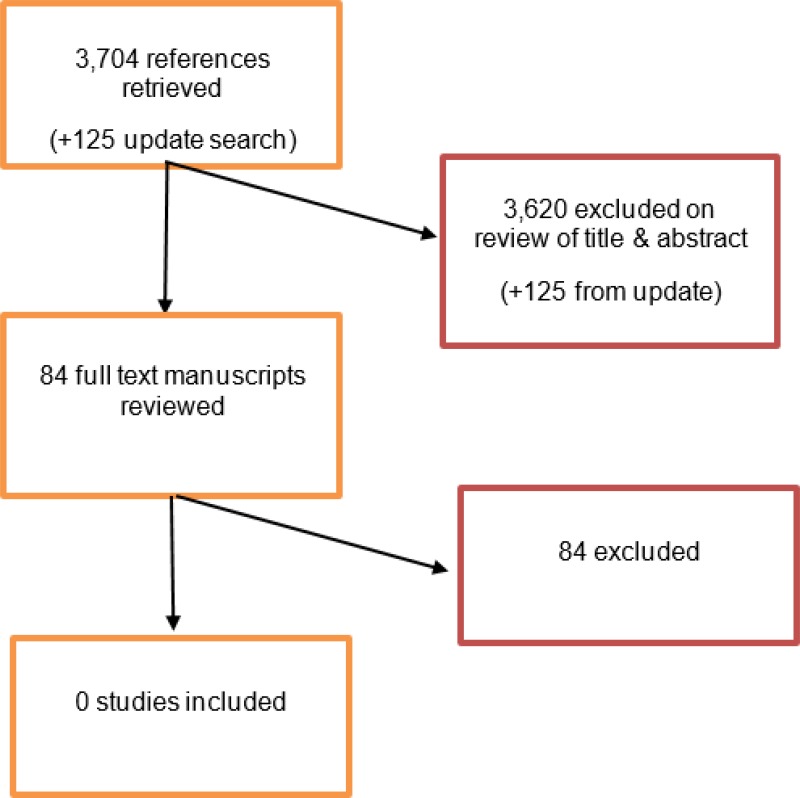

The database from initial literature searches provided 3,697 abstracts, and an additional 7 papers were identified through citation searching of studies screened at full-text. Of these 3,704 citations, 84 were identified as being potentially relevant. Following full-text review of these articles, 0 studies were found that met the criteria outlined in the protocol.

An update search was conducted in December 2017, to identify any relevant studies published during guideline development. The search yielded 125 abstracts; all of which were not considered relevant to this review question. As a result no additional studies were identified.

Excluded studies

For the list of studies excluded at full-text, with details, see Appendix E.

Summary of clinical studies included in the evidence review

No studies were included following full text review.

Quality assessment of clinical studies included in the evidence review

No studies were included following full text review.

Economic evidence

Included studies

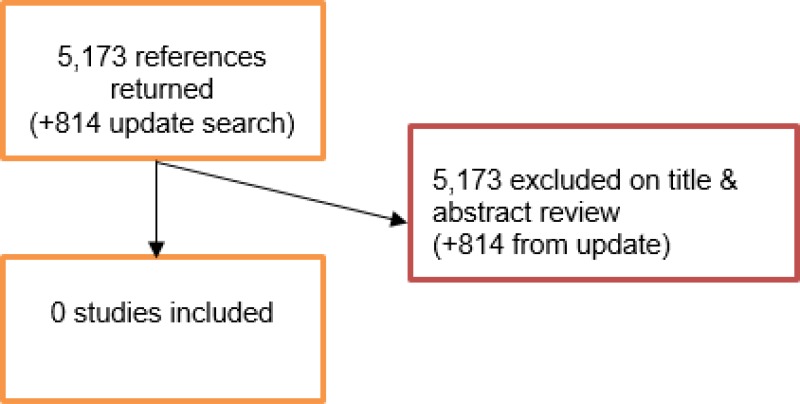

An initial literature search was conducted jointly for all review questions by applying standard health economic filters to a clinical search for AAA. This search returned a total of 5,173 citations. Following review of all titles and abstracts, no studies were identified as being potentially relevant to the review question. No full texts were retrieved, and no studies were included as economic evidence.

An update search was conducted in December 2017, to identify any relevant health economic analyses published during guideline development. The search yielded 814 abstracts; all of which were not considered relevant to this review question. As a result no additional studies were identified.

Excluded studies

No studies were retrieved for full-text review.

Evidence statements

No evidence was identified for this review question.

The committee’s discussion of the evidence

Interpreting the evidence

The outcomes that matter most

The committee agreed that the outcomes that matter most are the persistence or recurrence of endoleaks, AAA sac expansion and rupture which in turn poses a risk of mortality.

The quality of the evidence

No RCTs, quasi-randomised controlled trials or cohort studies with sample sizes of 500 or more were found. The committee discussed the potential usefulness of gathering evidence from small retrospective cohort studies and case series but agreed that none of these types of studies would have sufficient quality, or statistical power, to be useful for their decision making.

Benefits and harms

The committee noted that endoleaks pose a risk of sac expansion and rupture, and agreed that there are a variety of open, endovascular and percutaneous surgical interventions that can be used to resolve them. This in turn can prevent long-term complications that can have a negative impact on quality of life. They noted that endoleaks almost exclusively occur following EVAR as opposed to open repair, and therefore the informal consensus recommendations should be focused on people who have undergone surgical intervention via EVAR.

The committee agreed that, based on their clinical experience, type II endoleak, the most common form of post-EVAR endoleak, may be considered benign if found in the absence of signs of sac expansion. As such, a recommendation to consider intervention for type II endoleaks only in people who have sac expansion following EVAR discourages interventions that, in the absence of sac expansion, may be more harmful than beneficial.

The committee noted that it is common practice to intervene for the majority of type I and III endoleaks. However, the committee advised that for all endoleaks, even type I and III, there are instances in which practitioners would not intervene. The committee therefore agreed that a recommendation to ‘offer’ interventions for type I-III endoleaks should not be made, due to a lack of evidence and due to instances existing in which intervention for endoleaks would be inappropriate for the affected person.

The committee noted that type IV endoleaks can occur after some EVAR procedures, due to the porosity of certain graft materials, but usually resolve on their own without the need for intervention. As a result, it was agreed that no recommendations were needed in relation to type IV endoleaks.

The committee noted that a type V endoleak (also referred to as endotension) is a phenomenon in which there is continued sac expansion without imaging evidence of a leak site. Due to the risk of mortality associated with aneurysm sac expansion, the committee agreed that it would be appropriate to consider further investigations to identify the cause of sac expansion, and to see if the underlying cause is one that may be treatable.

The committee identified several risks of endoleak intervention but agreed that these were too small in magnitude and/or frequency to influence recommendations. These included small risks of procedural harm and the potential for over-treating and/or over-investigating people, particularly in those with difficult-to-treat endoleaks. There is also a small risk of radiation-induced malignancy associated with repeated exposure to ionising radiation during CT imaging. However, this risk was agreed to be small, because the average life expectancy following EVAR is too short for radiation-induced cancer to develop in most people undergoing endoleak surveillance or intervention.

For the other complications specified in this review (stent fractures and occlusions, graft infection, graft migration, aortoenteric fistula, secondary aortic rupture and ischaemic complications), the committee agreed it was neither possible nor useful to give consensus recommendations on how they should be managed. This was because there is established practice for their management, or a general lack of consensus as to best practice for management.

Cost effectiveness and resource use

The committee agreed that the recommendations are unlikely to impact on costs and resource use. This is because interventions for endoleaks and investigations for causes of aneurysm sac expansion are already performed in practice, and the recommendations reinforce their importance. The committee also noted that the costs associated with treating endoleaks would be offset by savings arising from the prevention of long-term complications associated with endoleak.

Other considerations

The committee agreed that there was no reason to believe that management of complications should be different between women and men, and therefore considered that the recommendations would apply to all people who have undergone EVAR.

Studies relating to the EUROSTAR registry were reviewed for inclusion. However, these assessed primarily incidence and prognosis of post-repair complications and none compared the efficacy of surgical interventions in the management of these complications.

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocols

Review protocol for managing post-surgery complications

| Review question 31 | How should the following complications be managed if they do arise?

|

|---|---|

| Objectives | To determine the most effective approach to managing endoleak, expanding aneurysm sac, stent fractures and occlusions, graft infection, graft migration, aortoenteric fistula, aortic rupture, and ischaemic complications (limb, visceral and renal) |

| Type of review | Intervention |

| Language | English only |

| Study design | Systematic reviews of study designs listed below

|

| Status |

Published papers only (full text) No date restrictions |

| Population | People who experience a complication (endoleak, expanding aneurysm sac, stent fractures and occlusions, graft infection, graft migration, aortoenteric fistula, aortic rupture, and ischaemic complications (limb, visceral and renal) after undergoing surgical repair of an AAA |

| Intervention | Open, endovascular or percutaneous surgical intervention |

| Comparator | Each other, no intervention, sham surgical intervention, or surveillance |

| Outcomes |

|

| Other criteria for inclusion / exclusion of studies | Exclusion:

|

| Baseline characteristics to be extracted in evidence tables |

|

| Search strategies | See Appendix B |

| Review strategies |

Appropriate NICE Methodology Checklists, depending on study designs, will be used as a guide to appraise the quality of individual studies. Data on all included studies will be extracted into evidence tables. Where statistically possible, a meta-analytic approach will be used to give an overall summary effect. All key findings from evidence will be presented in GRADE profiles and further summarised in evidence statements. |

| Key papers |

https://icvts |

Appendix B. Literature search strategies

Clinical search literature search strategy

Main searches

Bibliographic databases searched for the guideline

- Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature - CINAHL (EBSCO)

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews – CDSR (Wiley)

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials – CENTRAL (Wiley)

- Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects – DARE (Wiley)

- Health Technology Assessment Database – HTA (Wiley)

- EMBASE (Ovid)

- MEDLINE (Ovid)

- MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print (Ovid)

- MEDLINE In-Process (Ovid)

Identification of evidence for review questions

The searches were conducted between November 2015 and October 2017 for 31 review questions (RQ). In collaboration with Cochrane, the evidence for several review questions was identified by an update of an existing Cochrane review. Review questions in this category are indicated below. Where review questions had a broader scope, supplement searches were undertaken by NICE.

Searches were re-run in December 2017.

Where appropriate, study design filters (either designed in-house or by McMaster) were used to limit the retrieval to, for example, randomised controlled trials. Details of the study design filters used can be found in section 4.

Search strategy review question 31

|

Medline Strategy, searched 18th October 2017 Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to October Week 1 2017 Search Strategy: |

|---|

| 1 Aortic Aneurysm, Abdominal/ (18071) |

| 2 (aneurysm* adj4 (abdom* or thoracoabdom* or thoraco-abdom* or aort* or spontan* or juxtarenal* or juxta-renal* or juxta renal* or paraerenal* or para-renal* or para renal* or suprarenal* or supra renal* or supra-renal* or short neck* or short-neck* or shortneck* or visceral aortic segment*)).tw. (36093) |

| 3 AAA*.tw. (13513) |

| 4 or/1-3 (45989) |

| 5 exp Perioperative Care/ (149869) |

| 6 (postsurg* or post-surg* or post surg* or postop* or post-op* or post op* or post-endovascular* or post endovascular* or post endovascular*).tw. (513005) |

| 7 ((after or following or followed or electiv* or post*) adj4 (surg* or operat* or procedure* or repair* or care* or outcome*)).tw. (714418) |

| 8 or/5-7 (1062271) |

| 9 Elective Surgical Procedures/ (12513) |

| 10 Endovascular Procedures/ or Vascular Surgical Procedures/ (42604) |

| 11 (endovascular* adj4 aneurysm* adj4 repair*).tw. (4258) |

| 12 (endovascular adj4 aort* adj4 repair*).tw. (4633) |

| 13 (upper adj4 abdominal adj4 (repair* or surger* or surgic* or operat* or procedur*)).tw. |

| 14 (EVAR or EVRAR or FEVAR or F-EAVAR or BEVAR or B-EVAR).tw. |

| 15 (Anaconda or Zenith Dynalink or Hemobahn or Luminex* or Memoth-erm or Wallstent).tw. |

| 16 (Viabahn or Nitinol or Hemobahn or Intracoil or Tantalum).tw. |

| 17 or/9-16 |

| 18 4 and 8 and 17 |

| 19 Aortic Aneurysm, Abdominal/su [Surgery] |

| 20 8 and 19 |

| 21 18 or 20 |

| 22 (manag* adj4 complication*).tw. |

| 23 Endoleak/ |

| 24 Prosthesis Failure/ |

| 25 (endoleak or (perigraft* adj4 leak*)).tw. |

| 26 (prosthe* adj4 (fail* or loose* or migrat* or break* or fail*)).tw. |

| 27 Postoperative Hemorrhage/ |

| 28 (haemorrhag* or hemorrhag* or bleed* or blood-loss or bloodloss or blood loss).tw. |

| 29 (blood adj4 los*).tw. |

| 30 (expan* adj4 aneurysm* adj4 sac*).tw. |

| 31 (expan* adj4 AAA adj4 sac*).tw. |

| 32 (rupture* adj4 sac*).tw. |

| 33 Stents/ae [Adverse Effects] |

| 34 (stent* adj4 (fractur* or occlus*)).tw. |

| 35 Prosthesis-Related Infections/ |

| 36 ((prosthe* or graft* or endograft*) adj4 infect*).tw. |

| 37 ((graft* or endograft*) adj4 (fail* or loose* or migrat* or break* or fail*)).tw. |

| 38 Intestinal Fistula/ |

| 39 ((intestin* or cholecystoduoden* or colovesic* or enterocutan* or aortoenteric* or bowel* or enteric*) adj4 fistul*).tw. |

| 40 (aliment* adj4 tract* adj4 fistul*).tw. |

| 41 Aortic Rupture/ |

| 42 RAAA.tw. |

| 43 ((aort* or aneurysm*) adj4 ruptur*).tw. |

| 44 Ischemia/ |

| 45 ((limb* or lower-limb* or visceral* or intestin* or colon* or bowel* or mesenteric* or renal* or kidney* or nephric* or asnephric*) adj4 (ischaemi* or ischemi*)).tw. |

| 46 (blood adj4 deficien* adj4 (limb* or lower-limb* or visceral* or intestin* or colon* or bowel* or mesenteric* or renal* or kidney* or nephric* or asnephric*)).tw. |

| 47 (insufficien* adj4 blood adj4 (limb* or lower-limb* or visceral* or intestin* or colon* or bowel* or mesenteric* or renal* or kidney* or nephric* or asnephric*)).tw. |

| 48 (decreas* adj4 blood adj4 (limb* or lower-limb* or visceral* or intestin* or colon* or bowel* or mesenteric* or renal* or kidney* or nephric* or asnephric*)).tw. |

| 49 (reduc* adj4 blood adj4 (limb* or lower-limb* or visceral* or intestin* or colon* or bowel* or mesenteric* or renal* or kidney* or nephric* or asnephric*)).tw. |

| 50 (circulat* adj4 (disorder* or fail* or disturb*) adj4 (limb* or lower-limb* or visceral* or intestin* or colon* or bowel* or mesenteric* or renal* or kidney* or nephric* or asnephric*)).tw. |

| 51 or/22-50 |

| 52 21 and 51 |

| 53 animals/ not humans/ |

| 54 52 not 53 |

| 55 limit 54 to english language |

Health Economics literature search strategy

Sources searched to identify economic evaluations

- NHS Economic Evaluation Database – NHS EED (Wiley) last updated Dec 2014

- Health Technology Assessment Database – HTA (Wiley) last updated Oct 2016

- Embase (Ovid)

- MEDLINE (Ovid)

- MEDLINE In-Process (Ovid)

Search filters to retrieve economic evaluations and quality of life papers were appended to the population and intervention terms to identify relevant evidence. Searches were not undertaken for qualitative RQs. For social care topic questions additional terms were added. Searches were re-run in September 2017 where the filters were added to the population terms.

Health economics search strategy

| Medline Strategy |

|---|

| Economic evaluations |

| 1 Economics/ |

| 2 exp “Costs and Cost Analysis”/ |

| 3 Economics, Dental/ |

| 4 exp Economics, Hospital/ |

| 5 exp Economics, Medical/ |

| 6 Economics, Nursing/ |

| 7 Economics, Pharmaceutical/ |

| 8 Budgets/ |

| 9 exp Models, Economic/ |

| 10 Markov Chains/ |

| 11 Monte Carlo Method/ |

| 12 Decision Trees/ |

| 13 econom*.tw. |

| 14 cba.tw. |

| 15 cea.tw. |

| 16 cua.tw. |

| 17 markov*.tw. |

| 18 (monte adj carlo).tw. |

| 19 (decision adj3 (tree* or analys*)).tw. |

| 20 (cost or costs or costing* or costly or costed).tw. |

| 21 (price* or pricing*).tw. |

| 22 budget*.tw. |

| 23 expenditure*.tw. |

| 24 (value adj3 (money or monetary)).tw. |

| 25 (pharmacoeconomic* or (pharmaco adj economic*)).tw. |

| 26 or/1-25 |

| Quality of life |

| 1 “Quality of Life”/ |

| 2 quality of life.tw. |

| 3 “Value of Life”/ |

| 4 Quality-Adjusted Life Years/ |

| 5 quality adjusted life.tw. |

| 6 (qaly* or qald* or qale* or qtime*).tw. |

| 7 disability adjusted life.tw. |

| 8 daly*.tw. |

| 9 Health Status Indicators/ |

| 10 (sf36 or sf 36 or short form 36 or shortform 36 or sf thirtysix or sf thirty six or shortform thirtysix or shortform thirty six or short form thirtysix or short form thirty six).tw. |

| 11 (sf6 or sf 6 or short form 6 or shortform 6 or sf six or sfsix or shortform six or short form six).tw. |

| 12 (sf12 or sf 12 or short form 12 or shortform 12 or sf twelve or sftwelve or shortform twelve or short form twelve).tw. |

| 13 (sf16 or sf 16 or short form 16 or shortform 16 or sf sixteen or sfsixteen or shortform sixteen or short form sixteen).tw. |

| 14 (sf20 or sf 20 or short form 20 or shortform 20 or sf twenty or sftwenty or shortform twenty or short form twenty).tw. |

| 15 (euroqol or euro qol or eq5d or eq 5d).tw. |

| 16 (qol or hql or hqol or hrqol).tw. |

| 17 (hye or hyes).tw. |

| 18 health* year* equivalent*.tw. |

| 19 utilit*.tw. |

| 20 (hui or hui1 or hui2 or hui3).tw. |

| 21 disutili*.tw. |

| 22 rosser.tw. |

| 23 quality of wellbeing.tw. |

| 24 quality of well-being.tw. |

| 25 qwb.tw. |

| 26 willingness to pay.tw. |

| 27 standard gamble*.tw. |

| 28 time trade off.tw. |

| 29 time tradeoff.tw. |

| 30 tto.tw. |

| 31 or/1-30 |

Appendix E. Excluded studies

Clinical studies

| Short Title | Title | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| AbuRahma (2017) | Management of Immediate Post-Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair Type Ia Endoleaks and Late Outcomes | Full text screen

|

| Alvarez (2017) | Effect of antiplatelet therapy on aneurysmal sac expansion associated with type II endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Ammar (2016) | Comparative effect of propofol versus sevoflurane on renal ischemia/reperfusion injury after elective open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Argyriou (2017) | Endograft Infection After Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis | Full text screen

|

| Baril (2008) | Endovascular stent-graft repair of failed endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Bastos (2014) | Spontaneous delayed sealing in selected patients with a primary type-Ia endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Baum (2002) | Treatment of type II endoleaks after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: comparison of transarterial and translumbar techniques | Full text screen

|

| Burks (2001) | Endovascular repair of bleeding aortoenteric fistulas: a 5-year experience | Full text screen

|

| Capoccia (2016) | Preliminary Results from a National Enquiry of Infection in Abdominal Aortic Endovascular Repair (Registry of Infection in EVAR-R.I.EVAR). | Full text screen

|

| Choi (2011) | Treatment of type I endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm: usefulness of N-butyl cyanoacrylate embolization in cases of failed secondary endovascular intervention | Full text screen

|

| Darling (1999) | The incidence, natural history, and outcome of secondary intervention for persistent collateral flow in the excluded abdominal aortic aneurysm | Full text screen

|

| Davila (2015) | A multicenter experience with the surgical treatment of infected abdominal aortic endografts | Full text screen

|

| Donas (2015) | Use of parallel grafts to save failed prior endovascular aortic aneurysm repair and type Ia endoleaks | Full text screen

|

| Eli (2016) | Long-term outcomes of embolization of type II endoleaks | Full text screen

|

| Faries (2003) | Management of endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair: cuffs, coils, and conversion | Full text screen

|

| Ferrero (2013) | Open conversion after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair: a single-center experience | Full text screen

|

| Fichelle (1993) | Infected infrarenal aortic aneurysms: when is in situ reconstruction safe? | Full text screen

|

| Freischlag (2002) | Treatment of type 2 endoleaks after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: Comparison of transarterial and translumbar techniques: Discussion | Full text screen

|

| Gandini (2014) | Treatment of type II endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair: the role of selective vs. nonselective transcaval embolization | Full text screen

|

| Gallagher (2012) | Midterm outcomes after treatment of type II endoleaks associated with aneurysm sac expansion | Full text screen

|

| Gelfand (2006) | Clinical significance of type II endoleak after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm | Full text screen

|

| Gorich (2000) | Treatment of leaks after endovascular repair of aortic aneurysms | Full text screen

|

| Hajibandeh (2015) | Is intervention better than surveillance in patients with type 2 endoleak post-endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair? | Full text screen

|

| Halak (2007) | Open surgical treatment of aneurysmal sac expansion following endovascular abdominal aneurysm repair: solution for an unresolved clinical dilemma | Full text screen

|

| Jim (2011) | Midterm outcomes of the Zenith Renu AAA Ancillary Graft | Full text screen

|

| Jones (2007) | Persistent type 2 endoleak after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with adverse late outcomes | Full text screen

|

| Jouhannet (2014) | Reinterventions for type 2 endoleaks with enlargement of the aneurismal sac after endovascular treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms | Full text screen

|

| Kakkos (2011) | Open or endovascular repair of aortoenteric fistulas? A multicentre comparative study | Full text screen

|

| Karthikesalingam (2012) | Current evidence is insufficient to define an optimal threshold for intervention in isolated type II endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair. | Full text screen

|

| Katsargyris (2013) | Fenestrated stent-grafts for salvage of prior endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Khaja (2014) | Treatment of type II endoleak using Onyx with long-term imaging follow-up | Full text screen

|

| La Barbera (2003) | Aorto-caval fistula: A complication of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms | Full text screen

|

| Laser (2011) | Graft infection after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Law (2016) | Effectiveness of proximal intra-operative salvage Palmaz stent placement for endoleak during endovascular aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Leurs (2007) | Secondary interventions after elective endovascular repair of degenerative thoracic aortic aneurysms: results of the European collaborators registry (EUROSTAR) | Full text screen

|

| Lindblad (2008) | What to do when evidence is lacking - Implications on treatment of aortic ulcers, pseudoaneurysms and aorto-enteric fistulae | Full text screen

|

| Lynch (2004) | Clinical outcome and factors predictive of recurrence after enterocutaneous fistula surgery | Full text screen

|

| Maitrias (2016) | Treatment of sac expansion after endovascular aneurysm repair with obliterating endoaneurysmorrhaphy and stent graft preservation | Full text screen

|

| Maldonado (2004) | Ischemic complications after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Maleux (2001) | Late distal perigraft endoleak after endovascular repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm due to cranial migration of the iliac branch of a modular stent-graft | Full text screen

|

| Maleux (2017) | Incidence, etiology, and management of type III endoleak after endovascular aortic repair | Full text screen

|

| Marcelin (2017) | Safety and efficacy of embolization using Onyx of persistent type II endoleaks after abdominal endovascular aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Massis (2012) | Treatment of type II endoleaks with ethylene-vinyl-alcohol copolymer (Onyx). | Full text screen

|

| Maze (2013) | Outcomes of infected abdominal aortic grafts managed with antimicrobial therapy and graft retention in an unselected cohort | Full text screen

|

| Moulakakis (2017) | Treatment of Type II Endoleak and Aneurysm Expansion after EVAR | Full text screen

|

| Nevala (2010) | Type II endoleak after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: effectiveness of embolization | Full text screen

|

| Ogawa (2016) | A multi-institutional survey of interventional radiology for type II endoleaks after endovascular aortic repair: questionnaire results from the Japanese Society of Endoluminal Metallic Stents and Grafts in Japan | Full text screen

|

| Ozdemir (2013) | Embolisation of type 2 endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Patatas (2012) | Static sac size with a type II endoleak post-endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: surveillance or embolization? | Full text screen

|

| Pettersson (2017) | Aortic Graft Infections after Emergency and Non-Emergency Reconstruction: incidence, Treatment, and Long-Term Outcome | Full text screen

|

| Piffaretti (2017) | Operative Treatment of Type II Endoleaks Involving the Inferior Mesenteric Artery | Full text screen

|

| Pitoulias (2009) | Secondary endovascular and conversion procedures for failed endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: can we still be optimistic? | Full text screen

|

| Prokakis (2008) | Aortoesophageal fistulas due to thoracic aorta aneurysm: surgical versus endovascular repair. Is there a role for combined aortic management? | Full text screen

|

| Ricotta (2010) | Endoleak management and postoperative surveillance following endovascular repair of thoracic aortic aneurysms | Full text screen

|

| Saito (2012) | Outcome of surgical repair of aorto-eosophageal fistulas with cryopreserved aortic allografts | Full text screen

|

| Sampram (2003) | Nature, frequency, and predictors of secondary procedures after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm | Full text screen

|

| Sarac (2012) | Long-term follow-up of type II endoleak embolization reveals the need for close surveillance | Full text screen

|

| Scali (2014) | Elective endovascular aortic repair conversion for type Ia endoleak is not associated with increased morbidity or mortality compared with primary juxtarenal aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Schmieder (2009) | Endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair: duplex ultrasound imaging is better than computed tomography at determining the need for intervention | Full text screen

|

| Schoell (2015) | Surgery for secondary aorto-enteric fistula or erosion (SAEFE) complicating aortic graft replacement: a retrospective analysis of 32 patients with particular focus on digestive management | Full text screen

|

| Seeger (2000) | Long-term outcome after treatment of aortic graft infection with staged extra-anatomic bypass grafting and aortic graft removal | Full text screen

|

| Sharif (2007) | Prosthetic stent graft infection after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Sheehan (2004) | Effectiveness of coiling in the treatment of endoleaks after endovascular repair | Full text screen

|

| Sheehan (2006) | Are type II endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair endograft dependent? | Full text screen

|

| Sidloff (2013) | Type II endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Skibba (2015) | Management of late main-body aortic endograft component uncoupling and type IIIa endoleak encountered with the Endologix Powerlink and AFX platforms | Full text screen

|

| Smeds (2016) | Treatment and outcomes of aortic endograft infection. | Full text screen

|

| Spanos (2016) | Systematic review and meta-analysis of migration after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Spanos (2017) | Laparoscopic ligation of inferior mesenteric artery for the treatment of type II endoleak after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Steinmetz (2004) | Type II endoleak after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: A conservative approach with selective intervention is safe and cost-effective | Full text screen

|

| Thomas (2010) | A comparative analysis of the outcomes of aortic cuffs and converters for endovascular graft migration | Full text screen

|

| Tolia (2005) | Type II endoleaks after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: natural history | Full text screen

|

| Tzortzis (2003) | Adjunctive procedures for the treatment of proximal type I endoleak: the role of peri-aortic ligatures and Palmaz stenting | Full text screen

|

| Uthoff (2012) | Direct percutaneous sac injection for postoperative endoleak treatment after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

| Vaislic (2016) | Three-Year Outcomes with the Multilayer Flow Modulator for Repair of Thoracoabdominal Aneurysms: a Follow-up Report from the STRATO Trial | Full text screen

|

| Vaislic (2017) | Four-year outcomes with the multilayer flow modulator for repair of thoracoabdominal aneurysms: a follow-up report from the STRATO trial | Full text screen

|

| Valentine (1998) | Gastrointestinal complications after aortic surgery | Full text screen

|

| van Lammeren (2010) | Long-term follow-up of secondary interventions after endovascular aneurysm repair with the AneuRx endoprosthesis: a single-center experience | Full text screen

|

| van Zeggeren (2013) | Incidence and treatment results of Endurant endograft occlusion | Full text screen

|

| Velazquez (2000) | Relationship between preoperative patency of the inferior mesenteric artery and subsequent occurrence of type II endoleak in patients undergoing endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms | Full text screen

|

| Vogt (1998) | Cryopreserved arterial allografts in the treatment of major vascular infection: a comparison with conventional surgical techniques | Full text screen

|

| Walker (2015) | Type II endoleak with or without intervention after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair does not change aneurysm-related outcomes despite sac growth | Full text screen

|

| Wang (2017) | Limb graft occlusion following endovascular aortic repair: Incidence, causes, treatment and prevention in a study cohort | Full text screen

|

| Zacharias (2016) | Anatomic characteristics of abdominal aortic aneurysms presenting with delayed rupture after endovascular aneurysm repair | Full text screen

|

Economic studies

No full text papers were retrieved. All studies were excluded at review of titles and abstracts.

Appendix F. Glossary

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA)

A localised bulge in the abdominal aorta (the major blood vessel that supplies blood to the lower half of the body including the abdomen, pelvis and lower limbs) caused by weakening of the aortic wall. It is defined as an aortic diameter greater than 3 cm or a diameter more than 50% larger than the normal width of a healthy aorta. The clinical relevance of AAA is that the condition may lead to a life threatening rupture of the affected artery. Abdominal aortic aneurysms are generally characterised by their shape, size and cause:

- Infrarenal AAA: an aneurysm located in the lower segment of the abdominal aorta below the kidneys.

- Juxtarenal AAA: a type of infrarenal aneurysm that extends to, and sometimes, includes the lower margin of renal artery origins.

- Suprarenal AAA: an aneurysm involving the aorta below the diaphragm and above the renal arteries involving some or all of the visceral aortic segment and hence the origins of the renal, superior mesenteric, and celiac arteries, it may extend down to the aortic bifurcation.

- Abdominal compartment syndrome

Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs when the pressure within the abdominal cavity increases above 20 mm Hg (intra-abdominal hypertension). In the context of a ruptured AAA this is due to the mass effect of a volume of blood within or behind the abdominal cavity. The increased abdominal pressure reduces blood flow to abdominal organs and impairs pulmonary, cardiovascular, renal, and gastro-intestinal function. This can cause multiple organ dysfunction and eventually lead to death.

- Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET, sometimes also called CPX testing) is a non-invasive approach used to assess how the body performs before and during exercise. During CPET, the patient performs exercise on a stationary bicycle while breathing through a mouthpiece. Each breath is measured to assess the performance of the lungs and cardiovascular system. A heart tracing device (Electrocardiogram) will also record the hearts electrical activity before, during and after exercise.

- Device migration

Migration can occur after device implantation when there is any movement or displacement of a stent-graft from its original position relative to the aorta or renal arteries. The risk of migration increases with time and can result in the loss of device fixation. Device migration may not need further treatment but should be monitored as it can lead to complications such as aneurysm rupture or endoleak.

- Endoleak

An endoleak is the persistence of blood flow outside an endovascular stent - graft but within the aneurysm sac in which the graft is placed.

- Type I – Perigraft (at the proximal or distal seal zones): This form of endoleak is caused by blood flowing into the aneurysm because of an incomplete or ineffective seal at either end of an endograft. The blood flow creates pressure within the sac and significantly increases the risk of sac enlargement and rupture. As a result, Type I endoleaks typically require urgent attention.

- Type II – Retrograde or collateral (mesenteric, lumbar, renal accessory): These endoleaks are the most common type of endoleak. They occur when blood bleeds into the sac from small side branches of the aorta. They are generally considered benign because they are usually at low pressure and tend to resolve spontaneously over time without any need for intervention. Treatment of the endoleak is indicated if the aneurysm sac continues to expand.

- Type III – Midgraft (fabric tear, graft dislocation, graft disintegration): These endoleaks occur when blood flows into the aneurysm sac through defects in the endograft (such as graft fractures, misaligned graft joints and holes in the graft fabric). Similarly to Type I endoleak, a Type III endoleak results in systemic blood pressure within the aneurysm sac that increases the risk of rupture. Therefore, Type III endoleaks typically require urgent attention.

- Type IV– Graft porosity: These endoleaks often occur soon after AAA repair and are associated with the porosity of certain graft materials. They are caused by blood flowing through the graft fabric into the aneurysm sac. They do not usually require treatment and tend to resolve within a few days of graft placement.

- Type V – Endotension: A Type V endoleak is a phenomenon in which there is continued sac expansion without radiographic evidence of a leak site. It is a poorly understood abnormality. One theory that it is caused by pulsation of the graft wall, with transmission of the pulse wave through the aneurysm sac to the native aneurysm wall. Alternatively it may be due to intermittent leaks which are not apparent at imaging. It can be difficult to identify and treat any cause.

- Endovascular aneurysm repair

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is a technique that involves placing a stent –graft prosthesis within an aneurysm. The stent-graft is inserted through a small incision in the femoral artery in the groin, then delivered to the site of the aneurysm using catheters and guidewires and placed in position under X-ray guidance.

- Conventional EVAR refers to placement of an endovascular stent graft in an AAA where the anatomy of the aneurysm is such that the ‘instructions for use’ of that particular device are adhered to. Instructions for use define tolerances for AAA anatomy that the device manufacturer considers appropriate for that device. Common limitations on AAA anatomy are infrarenal neck length (usually >10mm), diameter (usually ≤30mm) and neck angle relative to the main body of the AAA

- Complex EVAR refers to a number of endovascular strategies that have been developed to address the challenges of aortic proximal neck fixation associated with complicated aneurysm anatomies like those seen in juxtarenal and suprarenal AAAs. These strategies include using conventional infrarenal aortic stent grafts outside their ‘instructions for use’, using physician-modified endografts, utilisation of customised fenestrated endografts, and employing snorkel or chimney approaches with parallel covered stents.

- Goal directed therapy

Goal directed therapy refers to a method of fluid administration that relies on minimally invasive cardiac output monitoring to tailor fluid administration to a maximal cardiac output or other reliable markers of cardiac function such as stroke volume variation or pulse pressure variation.

- Post processing technique

For the purpose of this review, a post-processing technique refers to a software package that is used to augment imaging obtained from CT scans, (which are conventionally presented as axial images), to provide additional 2- or 3-dimensional imaging and data relating to an aneurysm’s, size, position and anatomy.

- Permissive hypotension

Permissive hypotension (also known as hypotensive resuscitation and restrictive volume resuscitation) is a method of fluid administration commonly used in people with haemorrhage after trauma. The basic principle of the technique is to maintain haemostasis (the stopping of blood flow) by keeping a person’s blood pressure within a lower than normal range. In theory, a lower blood pressure means that blood loss will be slower, and more easily controlled by the pressure of internal self-tamponade and clot formation.

- Remote ischemic preconditioning

Remote ischemic preconditioning is a procedure that aims to reduce damage (ischaemic injury) that may occur from a restriction in the blood supply to tissues during surgery. The technique aims to trigger the body’s natural protective functions. It is sometimes performed before surgery and involves repeated, temporary cessation of blood flow to a limb to create ischemia (lack of oxygen and glucose) in the tissue. In theory, this “conditioning” activates physiological pathways that render the heart muscle resistant to subsequent prolonged periods of ischaemia.

- Tranexamic acid

Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic agent (medication that promotes blood clotting) that can be used to prevent, stop or reduce unwanted bleeding. It is often used to reduce the need for blood transfusion in adults having surgery, in trauma and in massive obstetric haemorrhage.

Final

Methods, evidence and recommendations

This evidence review was developed by the NICE Guideline Updates Team

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian.

Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties.

NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government, Scottish Government, and Northern Ireland Executive. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn.

- Managing complications after abdominal aortic aneurysm repairManaging complications after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...