NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002-.

PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet].

Show detailsThis PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood bladder cancer. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Date Last Modified") is the date of the most recent change. The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Childhood Bladder Cancer

Childhood bladder cancer is a very rare type of cancer that forms in the tissues of the bladder.

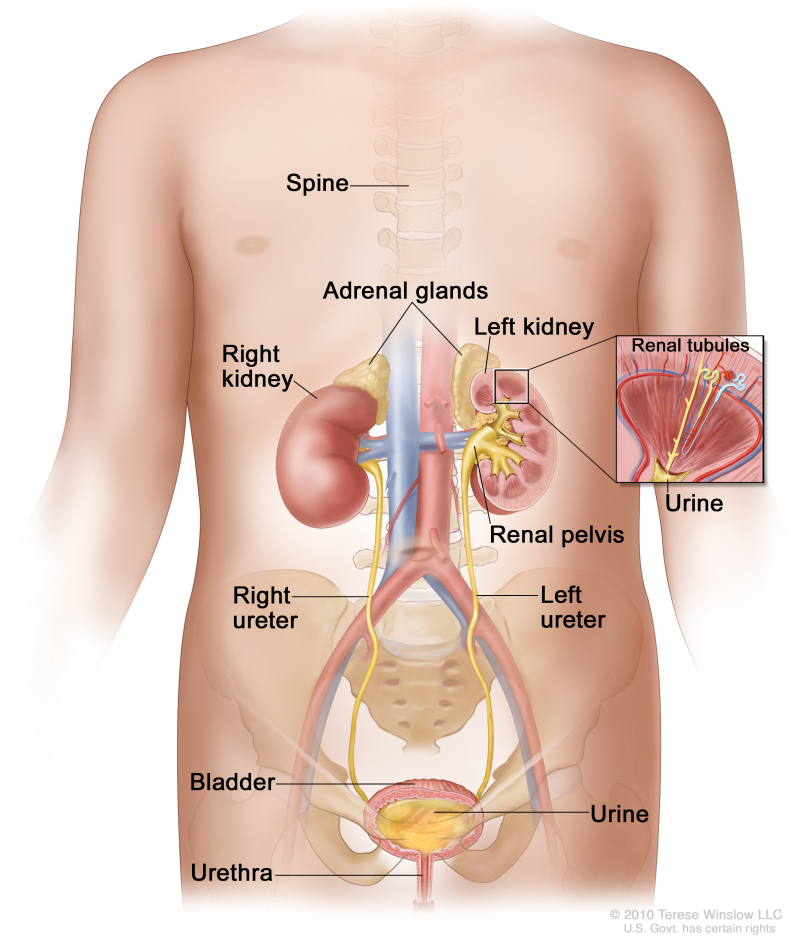

The bladder is a hollow, balloon-shaped organ in the lower part of the abdomen that stores urine. The bladder has a muscular wall that allows it to get larger to store urine made by the kidneys, and to shrink to squeeze urine out of the body. There are two kidneys, one on each side of the backbone, above the waist. The bladder and kidneys work together to remove toxins and wastes from the body through urine:

- Tiny tubules in the kidneys filter and clean the blood.

- These tubules take out waste products and make urine.

- The urine passes from each kidney through a long tube called a ureter into the bladder.

- The bladder holds the urine until it passes through the urethra and leaves the body.

Anatomy of the urinary system showing the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The inside of the left kidney shows the renal pelvis. An inset shows the renal tubules and urine. Also shown is the spine and adrenal glands. Urine is made in the renal tubules and collects in the renal pelvis of each kidney. The urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the bladder. The urine is stored in the bladder until it leaves the body through the urethra.

Urothelial carcinoma (also called transitional cell carcinoma) is cancer that begins in the urothelial cells, which line the urethra, bladder, ureters, renal pelvis, and some other organs. The cells of the urothelium are known as transitional cells because they are able to stretch when the bladder is full of urine and shrink when it is emptied. Urothelial carcinoma is the most common form of bladder cancer in children.

Squamous cell and other more aggressive types of bladder cancer are less common in children.

Bladder cancer can occur at any age and most often affects males.

Risk factors for childhood bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is caused by certain changes to the way bladder cells function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. Learn more about how cancer develops at What Is Cancer?

The risk of bladder cancer is increased in children who have been treated for cancer with certain anticancer drugs, called alkylating agents, which include cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, busulfan, and temozolomide. Survivors of heritable retinoblastoma also have an increased risk of developing bladder cancer. Not every child with these risk factors will develop bladder cancer. And it will develop in some children who don't have a known risk factor. Talk with your child’s doctor if you’re concerned about your child’s risk.

Symptoms of childhood bladder cancer

The symptoms of bladder cancer can vary from person to person. The most common symptom of bladder cancer is blood in the urine, called hematuria. It’s often slightly rusty to bright red in color. You may see blood in your child’s urine at one point, then not see it again for a while. Sometimes there are very small amounts of blood in the urine that can only be found by having a test done.

Other common symptoms of bladder cancer can include:

- frequent urination or feeling the need to urinate without being able to do so

- pain during urination

- abdominal or lower back pain

It’s important to check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of these symptoms. Keep in mind that urinary tract infections, kidney or bladder stones, or other problems related to the kidney could also be the cause, not cancer. Your child’s doctor will ask you when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They’ll most likely ask for a urine sample as a first step in diagnosing what is causing these symptoms.

Tests to diagnose childhood bladder cancer

If your child has symptoms or lab test results that suggest bladder cancer, their doctor will need to find out if these are due to cancer or another problem. They may:

- ask about your child’s personal and family medical history to learn more about your child’s symptoms and possible risk factors for bladder cancer

- do a physical exam to check for signs of cancer

- ask for a sample of urine so it can be checked in the lab for blood, abnormal cells, or infection

Depending on your child’s symptoms and medical history and the results of their physical exam and urine lab tests, the doctor may recommend more tests to find out if your child has bladder cancer, and if so, its extent (stage). The results of tests and procedures done to diagnose bladder cancer are used to help make decisions about treatment.

The following tests and procedures may be used:

CT scan (CAT scan)

A CT scan uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the pelvis. The pictures are taken from different angles and are used to create 3-D views of tissues and organs. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography. Learn more about Computed Tomography (CT) Scans and Cancer.

Ultrasound exam

An ultrasound exam uses high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) that bounce off internal tissues or organs, such as the pelvis, and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram.

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy is a procedure in which the doctor looks inside the bladder and urethra (the tube that carries urine out of your body) to check for abnormal areas. A cystoscope is slowly inserted through the urethra into the bladder to allow the doctor to see inside. A cystoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove very small tumors or tissue samples for biopsy. If a cystoscopy is not done at diagnosis, tissue samples are removed and checked for cancer during surgery to remove all or part of the bladder.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child’s bladder cancer diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans. They may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child’s tumor.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, see Finding Cancer Care. You can contact NCI’s Cancer Information Service via chat, email, or phone (both in English and Spanish) for help finding a doctor or hospital that can provide a second opinion. For questions you might want to ask at your child's appointments, see Questions to Ask Your Doctor about Cancer.

Prognosis of childhood bladder cancer

If your child has been diagnosed with bladder cancer, you likely have questions about how serious the cancer is and your child’s chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

The prognosis can be affected by whether the cancer can be removed by surgery. In children, bladder cancer is usually low grade (not likely to spread) and the prognosis is usually excellent after surgery to remove the tumor.

Types of treatment for childhood bladder cancer

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with bladder cancer. You and your child’s cancer care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child’s overall health and whether the cancer is newly diagnosed or has come back.

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, will oversee treatment for childhood bladder cancer. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with cancer and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. Other specialists may include:

- pediatric urologist

Your child’s treatment plan will include information about the cancer, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child’s cancer care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, see our downloadable booklet, Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Types of treatment your child might have include:

Surgery

Surgery to remove the cancer and part or all of the bladder is the standard treatment for bladder cancer in children. The type of surgery depends on where the cancer is located and whether it is aggressive.

Talk with your child’s doctor about how surgery for bladder cancer can affect urinating, sexual function, and fertility. Learn more about Fertility Issues in Girls and Women with Cancer and Fertility Issues in Boys and Men with Cancer.

Transurethral resection (TUR)

During TUR, the doctor removes tissue from the bladder using a resectoscope inserted into the bladder through the urethra. A resectoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light, a lens for viewing, and a tool to remove tissue and burn away any remaining tumor cells. Tissue samples from the area where the tumor was removed are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

Cystectomy

Cystectomy, surgery to remove part or all of the bladder, is rarely used to treat bladder cancer in children. However, it may be needed in children with squamous cell carcinoma or more aggressive carcinomas.

Clinical trials

For some children, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for childhood cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials accepting participants. The search allows you to filter trials based on the type of cancer, your child's age, and where the trials are being done. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Treatment of childhood bladder cancer

Treatment of newly diagnosed bladder cancer in children is usually surgery:

- transurethral resection (TUR)

- surgery to remove the bladder (rare)

Learn more about these treatments in the Types of treatment section.

Sometimes bladder cancer can recur (come back) after treatment. If your child is diagnosed with recurrent bladder cancer, your child's doctor will work with you to plan treatment.

Side effects and late effects of cancer treatment

Learn more about Side Effects of Cancer Treatment.

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include:

- physical problems

- changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory

- second cancers (new types of cancer) or other conditions

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the possible late effects caused by some treatments. Learn more about Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer.

Follow-up care

Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer may be repeated to see how well the treatment worked.

If the bladder cancer recurs (comes back) after treatment, it will usually be within 3 years from diagnosis. Your child will receive tests from time to time after surgery to find out if their condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred. These tests are sometimes called follow-up tests or check-ups.

Coping and support

When a child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is also important. Reach out to your child’s treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, see Support for Families: Childhood Cancer.

- Review Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Review Childhood Heart Tumors (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Heart Tumors (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Review Childhood Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Review Childhood Chordoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Chordoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Review Childhood Mesothelioma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.[PDQ Cancer Information Summari...]Review Childhood Mesothelioma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002

- Childhood Bladder Cancer Treatment - PDQ Cancer Information SummariesChildhood Bladder Cancer Treatment - PDQ Cancer Information Summaries

- Primary Liver Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information SummariesPrimary Liver Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information Summaries

- Communication in Cancer Care (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information SummariesCommunication in Cancer Care (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information Summaries

- Prostate Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information SummariesProstate Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information Summaries

- Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancers Screening (PDQ®) - PDQ C...Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancers Screening (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information Summaries

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...