All rights reserved. The publication contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the Thalassaemia International Federation.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Taher A, Vichinsky E, Musallam Ket al., authors; Weatherall D, editor. Guidelines for the Management of Non Transfusion Dependent Thalassaemia (NTDT) [Internet]. Nicosia (Cyprus): Thalassaemia International Federation; 2013.

This publication is provided for historical reference only and the information may be out of date.

Guidelines for the Management of Non Transfusion Dependent Thalassaemia (NTDT) [Internet].

Show detailsILLUSTRATIVE CASE

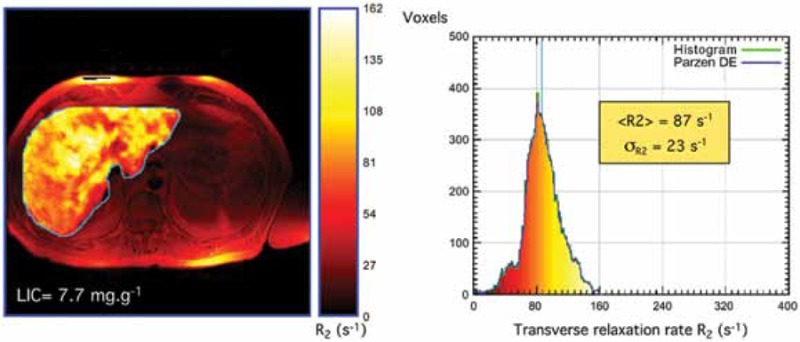

A 54-year-old man was diagnosed with β-thalassemia intermedia at the age of 5 years. He had been transfusion-independent for most of his life, and only received sporadic transfusions during a surgery and an episode of infection. He underwent splenectomy for splenomegaly in childhood and had been maintained on hydroxyurea therapy with a stable hemoglobin level between 7 and 8 g/dl. The patient presented to his physician with right upper quadrant pain that has been persistent for two months. Initial imaging with ultrasonography and computed tomography showed foci in his liver which were initially interpreted by the radiologist as extramedullary hematopoietic pseudotumors. Liver function tests were within normal range. His ferritin level was 1100 ng/ml and his liver iron concentration was also measured by R2 magnetic resonance imaging and was 14.3 mg Fe/g dry weight. A computed tomography-guided biopsy was recommended and showed the lesions to be compatible with multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatitis B and C testing by polymerase chain reaction were negative. The patient received palliative treatment. He developed hepatorenal syndrome and rapidly succumbed to his illness.

CONTEXT AND EVIDENCE

Although viral hepatitis is mainly a concern in the subgroup of NTDT patients who eventually require blood transfusion therapy (see Chapter 2), primary iron overload in patients with NTDT leads to preferential portal and hepatocyte iron loading and considerably elevated liver iron concentration (see Chapter 5). Data from patients with hereditary hemochromatosis and other acquired liver disease states continue to confirm the role of chronic hepatocellular iron deposition in promoting liver fibrogenesis and cirrhosis [1]. A longer duration of hepatic iron exposure is associated with a higher risk of significant fibrosis [2], while liver cirrhosis can develop within a decade in severely iron overloaded patients [3]. Studies on hepatic outcomes in patients with NTDT remain scarce. Abnormal liver function tests (alanine transaminase >50 IU/l) are noted in iron overloaded and older patients with NTDT [4-5]. A recent longitudinal study of a cohort of 42 never-transfused β-thalassemia intermedia adults followed for four years (median age 38 years) evaluated the association between longitudinal changes in serum ferritin levels and transient elastography values [6]. Transient elastography is a recently developed, rapid, noninvasive technique designed to predict hepatic fibrosis, based on a mechanical wave generated by vibration. The measurement of the speed of propagation of the wave across the hepatic parenchyma provides an estimate of the liver elasticity, which is a surrogate marker of liver fibrosis. When compared with liver biopsy, transient elastography shows a satisfactory sensitivity and specificity for identifying fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease including β-thalassemia, and has a good inter-observer and intra-observer reproducibility [7]. A significant increase was observed in both serum ferritin levels (+81.2 [ng/ml]/year) and transient elastography values in non-chelated patients (n=28) (+0.3 kPa/year), with two patients worsening their fibrosis stage. Chelated patients (n=14) had a significant decrease in both measures (−42.0 [ng/ml]/year and −0.9 kPa/year, respectively), with two patients improving their fibrosis stage. There was a strong correlation between the rate of change in serum ferritin level and the rate of change in transient elastography value (R2: 0.836, p<0.001); noted in both non-chelated and chelated patients [6]. Another recent 10-follow-up study confirmed an association between higher serum ferritin levels (≥800 ng/ml) and liver disease in non-chelated β-thalassemia intermedia patients [8].

The proliferative and mutagenic effects of excess iron are established, which converge in determining an increased susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma, even in the absence of pre-existing liver cirrhosis [1, 9-11]. Iron overload produces oxygen-free radicals. Oxidative damage can in turn give rise to neoplastic clones through genetic or epigenetic alterations. Iron overload can also suppress tumoricidal action of macrophages and alteration of cytokine activities. Iron chelation therapy, however, can exert protective effects on cell cycle control molecules and on nuclear factor-κB and has a protective effect against the oxygen radicals and proto-oncogene expression [12-13]. Several cases of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with NTDT (primarily β-thalassemia intermedia) have been described. A total of 22 patients with β-thalassemia intermedia developing hepatocellular carcinoma have been reported in the literature, out of which 6 developed malignancy in the absence of viral hepatitis or cirrhosis while having considerably high iron overload indices [14-18].

PRACTICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

- Patients with NTDT ≥10 years should be screened for hepatic function and disease as follows:

- > Liver function tests: every 3 months, all patients

- > Liver ultrasound: annually in patients with liver iron concentration ≥5 mg Fe/g dry weight or serum ferritin level ≥800 ng/ml

- > Alpha-feto protein: annually in cirrhotic patients or patients >40 years

- > Transient elastography monitoring may be administered when available, annually in patients with liver iron concentration ≥5 mg Fe/g dry weight or serum ferritin level ≥800 ng/ml

- NTDT patients with evidence of hepatic disease should be referred to a hepatologist for further work-up and management

- NTDT patients should be closely monitored and adequately managed for iron overload (see Chapter 5)

- Vaccination against hepatitis B prior to the initiation of any planned blood transfusion therapy, with regular monitoring of antibody titers, is recommended

- Vaccination against hepatitis A virus is recommended

- Patients receiving blood transfusions should undergo annual serologic monitoring for hepatitis B and C infections. In patients with evidence of hepatitis B and C infection upon serologic testing, confirmatory tests with a polymerase chain reaction should be done

- In patients with confirmed hepatitis B and C infection on polymerase chain reaction, management should follow guidelines from transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia major patients. A hepatologist should be consulted to decide on the indications for treatment, drug choices, dosing, and safety monitoring

REFERENCES

- 1.

- Fargion S, Valenti L, Fracanzani AL. Beyond hereditary hemochromatosis: new insights into the relationship between iron overload and chronic liver diseases. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(2):89–95. [PubMed: 20739232]

- 2.

- Olynyk JK, St Pierre TG, Britton RS, Brunt EM, Bacon BR. Duration of hepatic iron exposure increases the risk of significant fibrosis in hereditary hemochromatosis: a new role for magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):837–841. [PubMed: 15784029]

- 3.

- Olivieri NF. Progression of iron overload in sickle cell disease. Semin Hematol. 2001;38(1) Suppl 1:57–62. [PubMed: 11206962]

- 4.

- Taher AT, Musallam KM, Karimi M, El-Beshlawy A, Belhoul K, Daar S, Saned MS, El-Chafic AH, Fasulo MR, Cappellini MD. Overview on practices in thalassemia intermedia management aiming for lowering complication rates across a region of endemicity: the OPTIMAL CARE study. Blood. 2010;115(10):1886–1892. [PubMed: 20032507]

- 5.

- Taher AT, Musallam KM, El-Beshlawy A, Karimi M, Daar S, Belhoul K, Saned MS, Graziadei G, Cappellini MD. Age-related complications in treatment-naive patients with thalassaemia intermedia. Br J Haematol. 2010;150(4):486–489. [PubMed: 20456362]

- 6.

- Musallam KM, Motta I, Salvatori M, Fraquelli M, Marcon A, Taher AT, Cappellini MD. Longitudinal changes in serum ferritin levels correlate with measures of hepatic stiffness in transfusion-independent patients with beta-thalassemia intermedia. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2012;49(3)(4):136–139. [PubMed: 22727143]

- 7.

- Fraquelli M, Cassinerio E, Roghi A, Rigamonti C, Casazza G, Colombo M, Massironi S, Conte D, Cappellini MD. Transient elastography in the assessment of liver fibrosis in adult thalassemia patients. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(8):564–568. [PubMed: 20658587]

- 8.

- Musallam KM, Cappellini MD, Daar S, Karimi M, El-Beshlawy A, Taher AT. Serum ferritin levels and morbidity in β-thalassemia intermedia: a 10-year cohort study [abstract] Blood. 2012;120(21):1021.

- 9.

- Moyo VM, Makunike R, Gangaidzo IT, Gordeuk VR, McLaren CE, Khumalo H, Saungweme T, Rouault T, Kiire CF. African iron overload and hepatocellular carcinoma (HA-7-0-080). Eur J Haematol. 1998;60(1):28–34. [PubMed: 9451425]

- 10.

- Turlin B, Juguet F, Moirand R, Le Quilleuc D, Loreal O, Campion JP, Launois B, Ramee MP, Brissot P, Deugnier Y. Increased liver iron stores in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma developed on a noncirrhotic liver. Hepatology. 1995;22(2):446–450. [PubMed: 7635411]

- 11.

- Kowdley KV. Iron, hemochromatosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. gastroenterology. 2004;127(5) Suppl 1:S79–S86. [PubMed: 15508107]

- 12.

- Poggi M, Sorrentino F, Pascucci C, Monti S, Lauri C, Bisogni V, Toscano V, Cianciulli P. Malignancies in beta-thalassemia patients: first description of two cases of thyroid cancer and review of the literature. Hemoglobin. 2011;35(4):439–446. [PubMed: 21797713]

- 13.

- Huang X. Iron overload and its association with cancer risk in humans: evidence for iron as a carcinogenic metal. Mutat Res. 2003;533(1)(2):153–171. [PubMed: 14643418]

- 14.

- Borgna-Pignatti C, Vergine G, Lombardo T, Cappellini MD, Cianciulli P, Maggio A, Renda D, Lai ME, Mandas A, Forni G, Piga A, Bisconte MG. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the thalassaemia syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2004;124(1):114–117. [PubMed: 14675416]

- 15.

- Mancuso A, Sciarrino E, Renda MC, Maggio A. A prospective study of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in thalassemia. Hemoglobin. 2006;30(1):119–124. [PubMed: 16540424]

- 16.

- Restivo Pantalone G, Renda D, Valenza F, D’Amato F, Vitrano A, Cassara F, Rigano P, Di Salvo V, Giangreco A, Bevacqua E, Maggio A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with thalassaemia syndromes: clinical characteristics and outcome in a long term single centre experience. Br J Haematol. 2010;150(2):245–247. [PubMed: 20433678]

- 17.

- Maakaron JE, Cappellini MD, Graziadei G, Ayache JB, Taher AT. Hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis-negative patients with thalassemia intermedia: a closer look at the role of siderosis. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12(1):142–146. [PubMed: 23293206]

- 18.

- Maakaron JE, Musallam KM, Ayache JB, Jabbour M, Tawil AN, Taher AT. A liver mass in an iron-overloaded thalassaemia intermedia patient. Br J Haematol. 2013;161(1):1. [PubMed: 23294457]

- LIVER DISEASE - Guidelines for the Management of Non Transfusion Dependent Thala...LIVER DISEASE - Guidelines for the Management of Non Transfusion Dependent Thalassaemia (NTDT)

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...