A number of legal issues can affect HIV-infected clients and the operations of substance abuse treatment programs. With multiple sets of rules governing HIV/AIDS as well as substance abuse treatment, compliance can be tricky. This chapter examines legal issues (many of them with ethical implications) in two main areas:

- 1.

Access to services and programs, as well as employment opportunities for recovering substance abusers and persons living with HIV/AIDS

- 2.

Confidentiality, or the protection of clients' right to privacy

Both of these areas are covered by Federal and State laws, which are often attempts to address the ethical concerns involved.

Access to Treatment—Issues of Discrimination

Substance abuse treatment providers may encounter discrimination against their clients as they try to connect them with services. Although people have come a long way from the early days of the AIDS pandemic (when people were afraid to have any contact with someone infected with HIV), there are still many instances in which people living with HIV/AIDS are shunned, excluded from services, or offered services under discriminatory conditions. As recently as 1998, the United States Supreme Court considered a case against a dentist who refused to treat a patient in his office. He stated he would only treat her in a hospital (although her situation did not warrant an admission) and that she would have to incur those costs herself.

People in substance abuse treatment also may encounter outright rejection or discrimination because of their history of drug or alcohol use. A hospital might be unwilling to admit a client who relapses periodically. Or a long-term care facility may be reluctant to accommodate a client who is maintained on methadone.

Individuals living with HIV/AIDS and persons in substance abuse treatment may also encounter discrimination in employment. A school may refuse to hire a teacher who is HIV positive, or a business may fire a secretary when it discovers she once was treated for alcoholism.

This section outlines the protections Federal law currently affords people with substance abuse problems and people living with HIV/AIDS, as well as the limitations of those protections. State laws that outlaw discrimination against individuals with disabilities are also mentioned.

Federal Statutes Protecting People With Disabilities

Two Federal statutes protect people with disabilities: the Federal Rehabilitation Act (29 United States Code [U.S.C.] §791 et seq. [1973]) and the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) (42 U.S.C. 12101 et seq. [1992]). (In this section these are referred to collectively as “the acts.”) Together, these laws prohibit discrimination based on disability by private and public entities that provide most of the benefits, programs, and services a substance abuser or person living with HIV/AIDS is likely to need or seek. They also outlaw discrimination by a wide range of employers. For a general discussion about these Federal statutes, see TIP 29, Substance Use Disorder Treatment for People With Physical and Cognitive Disabilities (CSAT, 1998c).

Protections for substance abusers and persons living with HIV/AIDS

The issue for treatment providers is whether substance abusers and people living with HIV/AIDS are included in the definition of “individual with a disability.” The answer is yes in many, but not all, instances.

Alcohol abusers

In general, these acts protect alcohol abusers who are seeking benefits or services from an organization or agency covered by one of the statutes (29 U.S.C. §706(8)(C)(iii) and 42 U.S.C. §12110(c)), if they are “qualified” and do not pose a direct threat to the health or safety of others (28 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] §36.208(a)). This means that an organization or program cannot refuse to serve an individual unless

- ▪

The individual's alcohol use is so severe, or has resulted in other debilitating conditions, that he no longer “meets the essential eligibility requirements for the receipt of services or the participation in programs…with or without reasonable modifications to rules, policies, or practices ….” (42 U.S.C. §12131(2)).

- ▪

The individual poses “a significant risk to the health or safety of others that cannot be eliminated by a modification of policies, practices, or procedures, or by the provision of auxiliary aids or services” (36 CFR §36.208(b); Supplemental Information 28 CFR Part 35, Section-by-Section Analysis, §35.104).

For example, a hospital might take the position that an alcohol-dependent client with dementia was not “qualified” to participate in occupational therapy because he could not follow directions. Or an alcohol abuser whose drinking results in assaultive episodes that endanger elderly residents in a long-term care facility might pose the kind of “direct threat” to the health or safety of others that would permit his exclusion.

The Rehabilitation Act also permits programs and activities providing services of an educational nature to discipline students who use or possess alcohol (29 U.S.C. §706(8)(C)(iv)).

Abusers of illegal drugs

The acts divide abusers of illegal drugs into two groups: former abusers and current abusers.

Former abusers. Individuals who no longer are engaged in illegal use of drugs and have completed or are participating in a drug rehabilitation program are protected from discrimination to the same extent as alcohol abusers (29 U.S.C. §706(8)(C)(ii); 42 U.S.C. §12210(b)). In other words, they are protected so long as they are “qualified” for the program, activity, or service and do not pose a “direct threat” to the health or safety of others. Service providers may administer drug tests to ensure that an individual who once used illegal drugs no longer does so (28 CFR §36.209(c); 28 CFR §35.131(c)).

Current abusers. Individuals currently engaging in illegal use of drugs are offered full protection only in connection with health and drug rehabilitation services (28 CFR §36.209(b) and 28 CFR §35.131(b)). (However, drug treatment programs may deny participation to individuals who continue to use illegal drugs while they are in the program (28 CFR §36.209(b)(2)).) The laws explicitly withdraw protection with regard to other services, programs, or activities (29 U.S.C. §706(8)(C)(i) and 42 U.S.C. §2210(a)). Current illegal use of drugs is defined as “illegal use of drugs that occurred recently enough to justify a reasonable belief that a person's drug use is current or that continuing use is a real and ongoing problem” (28 CFR §35.104 and 28 CFR §35.104).

For example, a hospital that specializes in treating burn victims could not refuse to treat a burn victim because he uses illegal drugs, nor could it impose a surcharge on him because of his addiction. However, the hospital is not required to provide services that it does not ordinarily provide; for example, drug abuse treatment (Appendix B to 28 CFR Part 36, Section-by-Section Analysis, §36.302). On the other hand, a homeless shelter could refuse to admit an abuser of illegal drugs, unless the individual has stopped and is participating in or has completed drug treatment.

The Rehabilitation Act also permits programs and activities providing educational services to discipline students who use or possess illegal drugs (29 U.S.C. §706(8)(C)(iv)).

Individuals living with HIV/AIDS

Although alcohol and drug abuse are mentioned in both of the acts, HIV/AIDS is not. However, on June 25, 1998, the United States Supreme Court held that asymptomatic HIV infection is a “disability” under the ADA (Bragdon v. Abbott, 524 U.S. 624 [1998]. See also 28 CFR §35.104 and §36.104; 28 CFR Part 35, Section-by-Section Analysis, §35.104 and Appendix B to 28 CFR Part 36, Section-by-Section Analysis, §36.104). In this case, a woman with asymptomatic HIV disease sued a dentist who denied her equal service.

The Bragdon v. Abbott decision means that individuals living with HIV/AIDS are protected from discrimination under both of the acts, so long as they are “qualified” for the service, program, or benefit and do not pose a “direct threat” to the health or safety of others. (See also 28 CFR §36.208; Supplemental Information 28 CFR Part 35, Section-by-Section Analysis, §35.104.) An individual who is too ill to participate in a program, even with reasonable modifications, might not be “qualified.”

The “direct threat” question has received the most public attention. Can a “public accommodation,” a restaurant, hospital, school, or funeral home, refuse to provide services to someone living with HIV/AIDS because the person poses a “direct threat” to the health and safety of others? Because HIV is not transmitted by casual contact, and most programs and services provided by “public accommodations” involve only casual contact, the answer in most cases should be “no.” Even when contact with bodily fluids is likely to occur, public health authorities advise health care professionals to treat HIV-positive clients in the normal setting and to use universal precautions with all clients. Moreover, in those cases where a public accommodation could argue that an HIV-positive individual poses a direct threat, it would also have to show that the threat could not be eliminated by a modification of policies, practices, or procedures, or by the provision of auxiliary aids or services.

Protections in the area of employment

Alcohol-dependent and alcohol-abusing persons. The acts provide limited protection against employment discrimination to individuals who abuse alcohol but who can perform the requisite job duties and do not pose a direct threat to the health, safety, or property of others in the workplace (29 U.S.C. §706(8)(C)(v); 42 U.S.C. §12113(b); 42 U.S.C. §12111(3)). For example, the acts would protect an alcoholic secretary who binges on weekends but reports to work sober and performs her job safely and efficiently. However, a truck driver who comes to work inebriated and unable to do his job safely would not be protected. The employee whose promptness or attendance is erratic would not be protected either, unless the employer tolerated nonalcoholic-employee lateness and absences from work.

The ADA also permits an employer to

- ▪

Prohibit all use of alcohol in the workplace

- ▪

Require all employees to be free from the influence of alcohol at the workplace

- ▪

Require employees who abuse alcohol to maintain the same qualifications for employment, job performance, and behavior that the employer requires other employees to meet, even if any unsatisfactory performance is related to the employee's alcohol abuse (42 U.S.C. §12114(c))

Abusers of illegal drugs. Those who use or have used illegal drugs stand on a different footing. Former abusers who have completed or are participating in a drug rehabilitation program are offered some protection. The acts protect employees and prospective employees who

- ▪

Have successfully completed a supervised drug rehabilitation program or otherwise been rehabilitated and are no longer engaging in the illegal use of drugs

- ▪

Are participating in a supervised rehabilitation program and are no longer engaging in illegal drug use

- ▪

Are erroneously regarded as engaging in illegal drug use (29 U.S.C. 706(8)(C)(ii); 42 U.S.C. §12210(c))

Employers may administer drug testing to ensure that someone who has a history of illegal drug use is no longer using (29 U.S.C. §706(8)(C)(ii); 42 U.S.C. §12210(b); 28 CFR §36.209(c); 28 CFR §35.131(c)).

The ADA also permits an employer to

- ▪

Prohibit all use of illegal drugs in the workplace

- ▪

Require all employees to be free from the influence of illegal drugs at the workplace

- ▪

Require an employee who engages in the illegal use of drugs to maintain the same qualifications for employment, job performance, and behavior that the employer requires other employees to meet, even if any unsatisfactory performance is related to the employee's drug abuse (42 U.S.C. §12114(c))

The Drug-Free Workplace Act

Another Federal law, the Drug-Free Workplace Act (41 U.S.C. §701), may also affect clients in recovery. The Act requires employers who receive Federal funding through a grant (including block grant or entitlement grant programs) or who hold Federal contracts to certify they will provide a substance-free workplace. The certification means that affected employers must

- ▪

Notify employees that “the unlawful manufacture, distribution, dispensing, possession, or use of a controlled substance is prohibited in the workplace and specify the actions that will be taken against employees [who violate the] prohibition”

- ▪

Establish an ongoing substance-free awareness program to inform employees of the dangers of substance abuse in the workplace, the availability of any substance abuse counseling or employee assistance program, and the penalties that may be imposed for violations of the employer's policy

- ▪

Take appropriate action against an employee convicted of a substance abuse offense when the offense occurred in the workplace

- ▪

Notify the Federal funding agency in writing when such a conviction occurs

Current abusers have no protection against discrimination in employment, even if they are “qualified” and do not pose a “direct threat” to others in the workplace (29 U.S.C. §706(8)(C)(i); 42 U.S.C. §12210(a)).

People living with HIV/AIDS. The Supreme Court's decision in Abbott, that “disability” includes symptomatic and asymptomatic HIV disease, should apply in the area of employment. See also 28 CFR §35.104; Appendix to 29 CFR Part 1630C Interpretive Guidance on Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act, §1630.2(j) (“impairments…such as HIV infection, are inherently substantially limiting”). This means that an individual living with HIV/AIDS is protected from employment discrimination as long as he is “qualified,” that is, he can, with or without reasonable accommodation, perform the essential functions of the job and does not pose a “direct threat” to others in the workplace.

Reasonable accommodation can include a modified work schedule or reassignment to a vacant position. The “direct threat” issue has been most controversial and was left undecided by the court in Abbott. Can an employer running a restaurant, school, beauty salon, or construction company refuse to hire a person living with HIV/AIDS on the basis that the person poses a “direct threat” to coworkers, customers, or others in the workplace? Not if it bases its judgment solely on the individual's HIV/AIDS status. Because most employment involves only casual contact, an HIV-infected individual does not pose a risk to other employees, diners, students, or customers. Even in cases where an employer could argue that an HIV-infected individual poses a direct threat, it would also have to show that the threat could not be eliminated through a reasonable accommodation.

Therefore, in most cases, an employer could not refuse to hire and retain a person living with HIV/AIDS. However, if a person living with HIV/AIDS suffers from a physical condition such as blurred vision or dizziness that might pose a risk if he operates dangerous equipment, the employer might be justified in refusing to hire the person or curtailing the employee's activities after making the individualized assessment required by regulation (29 CFR §1630.2(r)).

The Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice has issued a useful “Q & A” about the ADA's protections for persons living with HIV/AIDS. It poses and answers questions about employment discrimination and discrimination by “public accommodations” and State and local governments and gives many helpful examples. It also contains a listing of places to find help.

State Laws

Most States have also enacted laws to protect people with disabilities (or “handicaps”). Some State laws protect alcohol abusers, drug abusers, and persons living with HIV/AIDS. Each State's laws are different, and a treatment provider seeking help under State law should make contact with the State or local agency charged with enforcing State civil rights laws. Such agencies often have the words “civil rights,” “human rights,” or “equal opportunity” in their titles.

Enforcement

Discrimination against substance abusers and individuals living with HIV/AIDS continues despite the existence of the acts. However, these laws offer those who believe they have suffered discrimination a choice of remedies.

For discrimination by program or activity

Filing a complaint with the Federal agency that funds the program, activity, or service (42 U.S.C. §12133; 29 U.S.C. §794(a); 28 CFR Part 35, Subparts F and G). For example, if the program is educational, it may receive funding from the Department of Education; if it involves health care, it may be funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Once a complaint is filed, one or more of the following actions will be taken:

- ▪

The agency will investigate and attempt an informal resolution.

- ▪

If a resolution is reached, the agency drafts a compliance agreement enforceable by the U.S. Attorney General.

- ▪

If no resolution is achieved, the agency issues a “Letter of Findings.” The Letter of Findings contains findings of fact, conclusions of law, a description of the suggested remedy, and a notice of the complainant's right to sue. A copy is sent to the U.S. Attorney General.

- ▪

The agency must then approach the offending program about negotiating. If the program refuses to negotiate or negotiations are fruitless, the agency refers the matter to the U.S. Attorney General with a recommendation for action.

Advantages: A complaint to the Federal funding agency may get the offending program's attention (and change its decision) because the funding agency has the power to deny future funding to those who violate the law. It is also inexpensive (no lawyer is necessary); however, if the complainant opts to be represented by an attorney, he may be awarded attorneys' fees if he prevails.

Disadvantage: Depending on the kind of complaint and which Federal agency has jurisdiction, this may not be the most expeditious route.

Filing a complaint with the State administrative agency charged with enforcement of the antidiscrimination laws (42 U.S.C. §12201(b)). Such agencies often have the words “civil rights,” “human rights,” or “equal opportunity” in their titles.

Advantage: This recourse is inexpensive.

Disadvantages: Some of these agencies have large backlogs that generally preclude speedy resolution of complaints. Depending on the State, remedies may be limited.

Filing a case in State or Federal court. One can file a court case requesting injunctive relief (temporary or permanent) and/or monetary damages. The court has the discretion to appoint a lawyer to represent the plaintiff (42 U.S.C. §§12188 and 2000a-3(a); 28 CFR §36.501).

Advantages: The complainant can ask for injunctive relief (a court order requiring the program to change its policy) and/or monetary damages. It may give the complainant a better sense of control over the process. A lawyer may produce results relatively quickly. A lawyer's approach to an offending program can have prompt and salutary effects. No one likes to be sued; it is costly, unpleasant, and often very public. It is often easier to re-examine one's position and settle the case quickly out of court.

Disadvantages: Unless one can find a not-for-profit organization that is interested in the case, a lawyer willing to represent the aggrieved party pro bono, or a lawyer willing to take the case on contingency or for the attorneys' fees the court can award the side that prevails, this may be an expensive alternative. It also may take a long time.

The advantages and disadvantages of filing a case in State court depend on State law, State procedural rules, and the speed with which cases are resolved.

Requesting enforcement action by the U.S. Attorney General. The Attorney General can file a lawsuit asking for injunctive relief, monetary damages, and civil penalties (42 U.S.C. §12188 and 2000a-3(a); 28 CFR §36.503).

For employment discrimination

Filing a complaint with the Federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) (42 U.S.C. §12117) or the State administrative agency charged with enforcement of antidiscrimination laws (42 U.S.C. §12201(b)).

- ▪

If the EEOC finds reasonable cause to believe that the charge of discrimination is true, and it cannot get agreement from the party charged, it can bring a lawsuit against any private entity. If the offending entity is governmental, the EEOC must refer the case to the U.S. Attorney General, who may file a lawsuit. The complainant can intervene in any court case brought by either the EEOC or the U.S. Attorney General.

- ▪

The EEOC or the U.S. Attorney General can also seek immediate relief by filing a motion for a preliminary injunction in a Federal court.

- ▪

The court can order injunctive relief, including reinstatement or hiring, back pay, and attorneys' fees (42 U.S.C. §2000e-5).

Advantage: A complaint to the EEOC, the U.S. Department of Justice, a State or local antidiscrimination agency, or State Attorney General is relatively inexpensive because it does not require a lawyer.

Disadvantage: Some of these agencies have large backlogs that generally preclude speedy resolution of complaints.

Filing a lawsuit in State or Federal court. After an aggrieved party has filed a complaint with the State administrative agency and/or the EEOC, he can file a lawsuit (42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f)).

Advantages: It may give the complainant better control over the process. The complainant can ask for injunctive relief (a court order requiring the employer to change its policy) and/or monetary damages. It can get relatively fast results. A lawyer's approach to an offending employer can have salutary effects. No one likes to be sued—it is costly, unpleasant, and often very public. It is often easier to reexamine one's position and settle the case quickly out of court.

Disadvantages: Unless one can find a not-for-profit organization that is interested in the case, a lawyer willing to represent the aggrieved party pro bono, or a lawyer willing to take the case on contingency or for the attorneys' fees the court can award the side that prevails, this may be an expensive alternative. It may also take a long time.

The alternatives listed here must be pursued within certain time limits established by State and Federal laws. An individual who is considering filing a complaint with any one of the agencies mentioned above should consult an attorney at an early date to determine when a complaint must be filed.

Summary of Protections

Federal law provides broad protection against discrimination by programs, services, and employers for individuals in substance abuse treatment who are also living with HIV/AIDS. Many States also have laws prohibiting discrimination against “individuals with disabilities” or “handicaps,” and some of these statutes also protect recovering substance abusers and individuals living with HIV/AIDS. To learn more about State law, the protections it offers, and the available remedies, providers can call the State or local “human rights,” “civil rights,” or “equal opportunity” agency. Advocacy groups for individuals with disabilities are also a good source of information. (An AIDS advocacy group would be particularly well informed.) Finally, local legal services offices, law school faculties, or bar associations may also have information available or may be able to provide an individual lawyer willing to make a presentation to staff.

Confidentiality of Information About Clients

Programs providing substance abuse treatment for clients living with HIV/AIDS frequently must communicate with individuals and organizations as they gather information, refer clients for services the program does not provide, and coordinate care with other service providers. On occasion, they are required to report information to the State. This section outlines the laws protecting client confidentiality and examines how staff can continue to provide appropriate treatment services, comply with State reporting laws, and protect client privacy.

Information about clients in substance abuse treatment who are living with HIV/AIDS is subject to two sets of laws:

- ▪

Federal statutes and regulations that guarantee the confidentiality of information about all persons applying for or receiving alcohol and drug abuse prevention, screening, assessment, and treatment services (42 U.S.C. §290dd-2; 42 CFR, Part 2)

- ▪

State laws governing the confidentiality of HIV/AIDS-related information. (State laws protecting HIV-related information vary in the protection they offer; some guard clients' privacy closely, others are more lenient. State laws also protect the confidentiality of other medical and mental health information. These laws, however, are likely to be less stringent than statutes dealing specifically with information about HIV/AIDS.)

The remainder of this chapter describes what these laws require and examines their impact on substance abuse treatment programs. The first section contains an overview of the Federal law protecting the right to privacy of any person who seeks or receives substance abuse treatment services. Because the Federal law applies throughout the country and preempts less restrictive State laws, this discussion focuses on how the Federal rules apply in a variety of situations, then addresses related State laws in those contexts. Next is an examination of the rules surrounding the use of consent forms to obtain a client's permission to release information, including ways to handle requests for disclosure when the client's file contains both substance abuse and HIV/AIDS information.

The third section reviews situations that commonly arise when a client in substance abuse treatment is living with HIV/AIDS, including how communications among agencies providing services to the client can be managed. The fourth section discusses exceptions in the Federal confidentiality rules that, in limited circumstances, permit disclosure of information about clients (e.g., reporting child abuse or neglect). The chapter ends with a few additional points concerning the requirement that clients receive a notice about the confidentiality regulations, clients' right to review their own records, and security of records.

Federal and State Laws Protect the Client's Right to Privacy

A Federal law and a set of regulations guarantee strict confidentiality of information about all persons who seek or receive alcohol and substance abuse assessment and treatment services. The legal citations for the laws and regulations are 42 U.S.C. §290dd-2 and 42 CFR Part 2. (Citations below in the form “§2…” refer to specific sections of 42 CFR Part 2.)

The Federal law and regulations are designed to protect clients' privacy rights in order to attract people into treatment. The regulations restrict communications tightly; unlike either the doctor-patient or the attorney-client privilege, the substance abuse treatment provider is prohibited from disclosing even the client's name. Violating the regulations is punishable by a fine of up to $500 for a first offense or up to $5,000 for each subsequent offense (§2.4).

The Federal rules apply to any program that specializes, in whole or in part, in providing treatment, counseling, or assessment and referral services for people with alcohol or drug problems (42 CFR §2.12(e)). Although the Federal regulations apply only to programs that receive Federal assistance, this includes indirect forms of Federal aid such as tax-exempt status, or State or local government funding coming (in whole or in part) from the Federal Government. Whether the Federal regulations apply to a particular program depends on the kinds of services the program offers, not the label the program chooses. Calling itself a “prevention program” or “outreach program” or “screening program” does not absolve a program from adhering to the confidentiality rules.

In the wake of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, many States have adopted laws protecting HIV/AIDS information. These laws are designed to encourage people at risk for HIV/AIDS to be tested, determine their HIV/AIDS status, begin medical treatment early, and change risky behaviors. Many State laws were passed with the concern that those who are seropositive will suffer discrimination in employment, medical care, insurance, housing, and other areas if their status becomes known. (Other State laws protect information about individuals' health, mental health status, or treatment, as well as information about other infectious diseases.)

The primary aim of confidentiality rules is to allow the client (and not the provider) to determine when and to whom information about medical or mental health, substance abuse, or HIV infection will be disclosed. Most of the nettlesome problems that may crop up under the State and Federal laws and regulations can be avoided through planning ahead. Familiarity with the rules will ease communication. It can also reduce the confidentiality-related conflicts among program, client, and outside agency or person to a few relatively rare situations.

General rules pertaining to confidentiality

Federal protections for substance abuse-related information

The Federal confidentiality law and regulations protect any information about a client who has applied for or received any service related to substance abuse treatment from a program that is covered under the law. Services can include screening, referral, assessment, diagnosis, individual counseling, group counseling, or treatment. The regulations are in effect from the time the client applies for or receives services or the program first conducts an assessment or begins to counsel the client. The restrictions on disclosure apply to any information that would identify the client as an alcohol or drug abuser, either directly or by implication. They also apply to former clients or patients. The rules apply whether or not the person making an inquiry about the client already has the information, has other ways of getting it, has some form of official status, is authorized by State law, or comes armed with a subpoena or search warrant. It should be noted, however, that if the person requesting information has a “special authorizing court order,” he does have the right to receive confidential information according to 42 CFR, Part 2.1

State protections for HIV/AIDS-related information

Whereas the Federal confidentiality rules apply throughout the country, each State has a different set of rules regarding disclosure of HIV/AIDS information. When substance abuse treatment programs hold HIV/AIDS-related information about clients, that information is protected by the Federal confidentiality regulations as well as by State law protecting HIV/AIDS-related information.

State protections for other medical and mental health-related information

State laws also offer general protection to some medical and mental health information. While any HIV/AIDS-specific confidentiality law is likely to be more stringent, providers should be aware of these more general statutes.2

When may confidential information be shared with others?

Although Federal and State law protect information about clients, the laws do contain exceptions. The most commonly used exception is the client's written consent. Although the Federal law protecting information about clients in substance abuse treatment and State laws protecting HIV/AIDS-related information both permit a client to consent to a disclosure, the consent requirements are likely to differ. Therefore, whenever providers contemplate making a disclosure of information about a client in substance abuse treatment who is living with HIV/AIDS, they must consider both Federal and State laws.

Federal Rules About Consent

The Federal regulations regarding consent are strict, somewhat unusual, and must be carefully followed. A proper consent form must be in writing and must contain each of the items below (§2.31):

- 1.

The name or general description of the program(s) making the disclosure

- 2.

The name or title of the individual or organization that will receive the disclosure

- 3.

The name of the client who is the subject of the disclosure

- 4.

The purpose or need for the disclosure

- 5.

How much and what kind of information will be disclosed

- 6.

A statement that the client may revoke (take back) the consent at any time, except to the extent that the program has already acted on it

- 7.

The date, event, or condition upon which the consent expires if not previously revoked

- 8.

The signature of the client

- 9.

The date on which the consent is signed

A general medical release form, or any consent form that does not contain all of the elements listed above, is not acceptable. (See sample consent form in Figure 9-1.) Most disclosures of information about a client in substance abuse treatment are permissible if the client has signed a valid consent form that has not expired or been revoked. (One exception to this statement may be when a client's file contains HIV/AIDS information, as discussed below.)

Figure 9-1

Sample Consent Form.

Items 4 through 7 in the above list deserve further explanation and are discussed in the sections that follow. Two other issues are also considered: the required notice to the recipient of the information that it may not be disclosed and the effect of a signed consent form.

Purpose of the disclosure and how much and what kind of information will be disclosed

These two items are closely related. All disclosures, and especially those made pursuant to a consent form, must be limited to the information necessary to accomplish the need or purpose for the disclosure (§2.13(a)). It is improper to disclose everything in a client's file if the recipient of the information needs only one specific piece of information.

A key step in completing the consent form is specifying the purpose or need for the communication of information. Once the purpose has been identified, it is easier to determine how much and what kind of information will be disclosed and to tailor it to what is essential to accomplish that particular purpose or need.

Client's right to revoke consent

Federal regulations permit the client to revoke consent at any time, and the consent form must include a statement to this effect. Revocation need not be in writing. If a program has already made a disclosure prior to the revocation, the program has acted in reliance on the consent and is not required to retrieve the information it has already disclosed.

Expiration of consent form

The Federal rules require that the consent form contain a date, event, or condition on which it will expire if not previously revoked. A consent form must last “no longer than reasonably necessary to serve the purpose for which it is given” (§2.31(a)(9)). If the purpose of the disclosure is expected to be accomplished in 5 or 10 days, it is better to fill in that amount of time rather than a longer period. It is best to determine how long each consent form should run rather than impose a set time period such as 60 or 90 days. When uniform expiration dates are used, agencies can find themselves in a situation requiring disclosure, after the client's consent form has expired. This means at the least that the client must return to the agency to sign a new consent form. At worst, the client has left or is unavailable (e.g., hospitalized), and the agency will not be able to make the disclosure.

The consent form need not contain a specific expiration date, but may instead specify an event or condition. For example, a form could expire after a client has seen a specific referred health care provider, or a consent form permitting disclosures to an employer might expire at the end of the client's probationary period.

The signature when the client is a minor (and the issue of parental consent)3

Minors must always sign the consent form in order for a program to release information, even with a parent's or guardian's consent. The program must obtain the parent's signature in addition to the minor's signature only if the program is required by State law to obtain parental permission before providing treatment to minors (§2.14). (“Parent” includes parent, guardian, or other person legally responsible for the minor.)

In other words, if State law does not require the program to obtain parental consent to provide services to a minor, then parental consent is not required to make disclosures (§2.14(b)). If State law requires parental consent to provide services to a minor, then parental consent is required to make any disclosures. The program must always obtain the minor's consent for disclosures and cannot rely on the parent's signature alone. Substance abuse treatment programs should consult with their Single State Authority or a local lawyer to determine whether they need parental consent to provide services to minors. For more information about minors, see TIP 31, Screening and Assessing Adolescents for Substance Use Disorders (CSAT, 1999a), and TIP 32, Treatment of Adolescents With Substance Use Disorders (CSAT, 1999b).

Required notice against redisclosing information

Once the consent form is properly completed, one last requirement remains. Any disclosure made with client consent must be accompanied by a written statement that the information disclosed is protected by Federal law and that the recipient of the information cannot further disclose it unless permitted by the regulations (§2.32). This statement, not the consent form itself, should be delivered and explained to the recipient at the time of disclosure or earlier.

The prohibition on redisclosure is clear and strict. Those who receive the notice are prohibited from re-releasing information except as permitted by the regulations. (Of course, a client may sign a consent form authorizing such a redisclosure.)

Note on the effect of a signed consent form

Programs may not disclose information when a consent form has expired, is deficient, is invalid or has been revoked (§2.31(c)). The other rules about how programs should respond to a signed consent form depend upon whether the disclosure will be to a third party or to the client himself and whether the client is a minor.

Disclosures to third parties

Programs subject to the Federal confidentiality rules are not required to disclose information to a third party about a client who has signed a consent form authorizing release of information unless the program has also been served with a subpoena or court order that meets the requirements of §2.3(b) and §2.61(a)(b). If the client consenting to disclosure is a minor (an issue governed by State law), the same rule applies. However, whether a consent form signed by a minor is valid depends upon whether State law permits a minor to enter treatment without parental consent. If State law permits a minor to enter treatment without parental consent, the program can rely on the minor client's signature on the consent form to make a disclosure to a third party. If State law requires parental consent for minors to enter treatment, then the program must get the signature of both parent and client. The minor must always sign the form.

Whenever a program releases information to a third party, it should disclose only what is necessary, and only as long as necessary, keeping in mind the purpose of the communication.

Disclosures to clients

If a client signs a consent form authorizing the program to disclose records directly to the client and State law requires the program to honor such a request, then the program must release the records to the client. (Note that the Federal law does not require clients to sign a proper consent form to obtain their own records, but State law may.) If the client signing the consent form authorizing release of information is a minor and the disclosure will be to his parent, guardian or other person or entity legally responsible for him, the program should make the disclosure. State law may mandate the disclosure and once the minor has consented, the program must follow the State rule. Even in States without such a rule mandating disclosure, only extraordinary circumstances could justify withholding information from a parent or guardian once the minor has consented to its release.

Special consent rules for clients mandated into treatment by the justice system

Substance abuse treatment programs treating clients who are involved in the criminal justice system (CJS) must also follow the Federal confidentiality regulations. However, some special rules apply when a client comes for assessment or treatment as an official condition of probation, sentence, dismissal of charges, release from detention, or other disposition of a criminal justice proceeding.

A consent form (or court order) is still required before a program can disclose information about a client who is the subject of CJS referral. For more detailed information about consent for clients within the CJS, see TIP 17, Planning for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Treatment for Adults in the Criminal Justice System (CSAT, 1995c).

State Rules About Consent

State laws that protect disclosure of HIV/AIDS-related information also contain an exception permitting most disclosures when the client consents. However, some States have strict requirements governing the content of the consent form. It is important, therefore, that programs providing substance abuse treatment to people living with HIV/AIDS become familiar with those requirements.

Which set of rules applies when a substance abuse treatment client with HIV/AIDS consents to a disclosure? This depends on what information is to be released, as illustrated in the following examples.

Example 1. Suppose a client's file contains both substance abuse treatment information and HIV/AIDS information, and the client wants to consent to disclosure of information about substance abuse to an outside agency but not information about HIV/AIDS status. This problem could be handled in several ways:

- ▪

The federally required consent form can be drafted narrowly so that the purpose for the disclosure and the kind of information to be disclosed are limited to substance abuse treatment.

- ▪

The program can maintain a filing system that isolates substance abuse and HIV/AIDS-related information in two different “treatment” or “medical” files and discloses only information from the “treatment” file. (This solution may not be practical, however, in States that regulate how and where HIV/AIDS-related information must be charted.)

- ▪

The program can send the client's file without the HIV/AIDS-related information to the outside agency and include the following notice (with the federally required notice of the prohibition on redisclosure):

This file does not contain any information protected by section ___ of the [State] law. The fact that this notice accompanies these records is NOT an indication that this client's file contains any information protected by section ___.

Example 2. If the client wants the program to release information about his HIV/AIDS status, the answer will be different. Clearly the State's form must be used. However, if the disclosure of the client's HIV/AIDS-related information will by implication or otherwise reveal that the client is in substance abuse treatment, the Federal form must also be used. For example, if the Satellite City Drug and Alcohol Program is the agency releasing HIV/AIDS-related information with a client's consent, the fact that the information came from a substance abuse treatment program will alert the recipient that the client is not only HIV positive but is also in substance abuse treatment. The program, therefore, must use a consent form that complies with both Federal and State requirements. It should not be necessary for clients to sign two separate forms in this kind of situation; a form that complies with both sets of requirements should be drafted.

Example 3. Finally, what happens when a client signs a proper consent form permitting disclosure of information about her substance abuse treatment, and the information she consents to release would also disclose her HIV/AIDS status? Can the program release the information? Not unless the program has complied with State consent requirements. Even if a client has signed a consent form permitting disclosure of substance abuse information, the program may not release information about HIV/AIDS unless it has also satisfied State requirements.

Strategies for Communication With Others About Clients

Some of the practical questions that affect program operations include the following:

- ▪

How can substance abuse treatment providers seek information from collateral sources about clients they are screening, assessing, or treating?

- ▪

How can providers comply with State mandatory reporting laws?

- ▪

How should providers deal with insurance companies and other third-party payors?

- ▪

How can providers respond to requests for information about clients who have died or become incompetent?

- ▪

How should programs deal with clients' risk-taking behavior? Do programs have a duty to warn potential victims or law enforcement agencies of clients' threats to plan to infect someone else with HIV/AIDS, and if so, how do they communicate the warning?

- ▪

Can staff members of substance abuse treatment programs comply with mandatory State child abuse reporting laws?

Seeking information from collateral sources

Making inquiries of family members, employers, schools, doctors, and other health care entities might seem to pose no risk to a client's right to confidentiality. This is not the case. When program staff seek information from other sources, they are letting these sources know that the client has asked for substance abuse treatment services. The Federal regulations generally prohibit this kind of disclosure unless the client consents.

How should a substance abuse treatment program proceed? The easiest way is to obtain the client's consent to contact the employer, family member, school, health care facility, etc. Or, the program could ask the client to sign a consent form that permits it to make a disclosure for the purpose of seeking information from other sources to any one of a number of organizations or persons listed on the consent form. Note that this combination form must still include “the name or title of the individual or the name of the organization” for each source the program contacts. Whichever method the program chooses, it must use the consent form required by the regulations, not a general medical release form.

If the client is living with HIV/AIDS, the program must check State laws to see whether they impose additional requirements. For example, an alcohol and drug counselor wishing to talk to a client's primary care physician must first find out whether State law protecting HIV/AIDS-related information requires that additional provisions be added to the consent form the client signs.

Making mandatory reports to public health authorities

All States require that AIDS and tuberculosis (TB) be reported to public health authorities, and some States also require that new cases of HIV infection be reported. The reports are forwarded to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). All States also use the TB report to perform contact tracing, or finding others to whom an infected person may have spread the disease; some States use HIV/AIDS reporting similarly.

In each State, what must be reported for which diseases, who must report, and the purposes for which the information is used vary. Therefore, providers must be familiar with their State laws regarding (1) whether they or any of their staff members are mandated to report, (2) when reporting is required, (3) what information must be reported and whether it includes client-identifying information, and (4) what will be done with the information reported.

Reporting HIV/AIDS and TB cases

If client-identifying information must be reported, how can programs comply with State laws mandating the reporting of TB and HIV/AIDS cases? Several ways are listed below.

Reporting with consent

The easiest way to comply is to obtain the client's consent. Note that if the public health authority plans to redisclose the information to the CDC, the consent form must be drafted to permit such redisclosure. The consent form can also be drafted to authorize the program to communicate on an ongoing basis with the public health department to help them find, counsel, monitor, or treat a client or coordinate a client's TB care.

Reporting without making a client-identifying disclosure

If State law permits the use of a code rather than the client's name, the program can make the report without the client's consent because no client-identifying information is being revealed. If the program is part of another health care facility, general hospital, or a mental health program, the report can include the client's name, if it does so under the name of the parent agency and releases no information that links the client with substance abuse treatment. (See the discussion below in “Communications that do not disclose client-identifying information.”)

Reporting through a Qualified Service Organization Agreement

A substance abuse treatment program can enter into a Qualified Service Organization Agreement (QSOA) with the State or local public health department charged with receiving mandatory reports. The QSOA (explained in more detail later in this chapter) permits the program to report names of clients to the health department and, if properly drafted, allows ongoing communication between the program and public health officials.

A program that is required to report TB or AIDS cases to a public health department can also enter into a QSOA with a general medical care facility or a laboratory that conducts testing or provides care to the program's clients. The QSOA would permit the program to report the names of clients to the medical care facility or laboratory, which can then report the information (including the clients' names) to the public heath department, without any information that would link those names with substance abuse treatment. Note that State confidentiality laws might impose additional requirements. Also, an agreement with a medical care facility or laboratory would not permit public health authorities to follow up on cases with the treatment program.

Reporting under the audit and evaluation exception

One exception to the general rule prohibiting disclosure without a client's consent permits programs under certain conditions to disclose information to auditors and evaluators (§2.53). (For an explanation of the requirements of §2.53, see TIP 14, Developing State Outcomes Monitoring Systems for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Treatment [CSAT, 1995a].) HHS has written two opinion letters that approve the use of the audit and evaluation exception to report HIV/AIDS-related information to public health authorities (see Pascal, 1988, and Zagame, 1989). Together, these two letters suggest that substance abuse treatment programs may report client-identifying information even if that information will be used by the public health department to conduct contact tracing, so long as the health department does not disclose the name of the client to “contacts” it approaches. The letters also suggest that public health authorities could use the information to contact the infected substance abuse disorder client directly.

However, some authorities may not agree with these opinion letters. As its title “audit and evaluation” implies, §2.53 is intended to permit an outside entity, such as a peer review organization or an accounting firm, to examine a program's records to determine whether it is operating appropriately. It is not intended to permit an outside entity such as the public health authority to gain information for other social ends, such as tracing the spread of disease. It can be argued that such use distorts the purpose of the audit and evaluation exception.

Getting a court order

A program could apply to a court for an order authorizing it to disclose information to a public health department. The court order provision is discussed further under “Exceptions that permit disclosures,” below. Since obtaining a court order requires drawing up legal papers, it is not likely to be a program's first choice.

Using the medical emergency exception

The Federal regulations permit a program to disclose information without client consent to medical personnel “who have a need for information about a client for the purpose of treating a condition which poses an immediate threat to the health” of the client or any other individual. The regulations define “medical emergency” as a situation that poses an immediate threat to health and requires immediate medical intervention (§2.51). (This exception is explained more fully later in this chapter.) Because any disclosure under this exception is limited to true emergencies, a program cannot routinely use the medical emergency exception to make mandatory reports. Because immediate medical intervention is unlikely to prevent or cure HIV infection, it is not an advisable way to make mandatory HIV/AIDS reports to public health departments.

For a more complete exploration of these options see TIP 18, The Tuberculosis Epidemic: Legal and Ethical Issues for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Treatment Providers (CSAT, 1995d).

Dealing with client risk-taking behavior

Does a program have a “duty to warn” others when it knows that a client is infected with HIV? When would that “duty” arise? Even where no duty exists, should providers warn others at risk about a client's HIV status? Finally, how can others be warned without violating the Federal confidentiality regulations and State confidentiality laws?

These questions raise complex legal issues that are discussed below. But first it must be noted that “warning” someone about a client's HIV status without his consent has potential consequences. Successful substance abuse treatment depends on clients' willingness to expose shameful things about themselves to program staff. The news that the program has “warned” a spouse, lover, or someone else that a client is HIV positive will spread quickly among the client population. Such news could destroy clients' trust in the program and its staff. Any counselor or program considering “warning” someone of a client's HIV status without the client's consent should carefully analyze whether there is, in fact, a “duty to warn” and whether it is possible to persuade the client to discharge this responsibility himself or consent to the program's doing so.

Is there a duty?

The answer is a matter of State law. Courts in some States hold that health care providers have a duty to warn third parties of behavior of persons under their care that poses a potential danger to others. In addition to these court decisions, some States have laws that either permit or require health care providers to warn certain third parties. Usually, these State laws prohibit disclosure of the infected person's identity but allow the provider to tell the person at risk that she may have been exposed. It is important that providers consult with an attorney familiar with State law to learn whether the law imposes a duty to warn, as well as whether State law prescribes the ways a provider can notify the person at risk. The law in this area is still developing and may expand; thus, it is important to keep abreast of changes. One source of information about State codes with regard to the duty to warn is each State's Web site (available at http://janus.state.me.us/states.htm). (If there is no State statute or court decision on this issue, it is best to consult with a lawyer or someone with expertise in this area who can help the program determine the best course to take. Such a consultation is particularly helpful because of the competing obligations the program may have to protect a third party who may be in danger and to safeguard its client's confidentiality.)

When does the duty arise?

Two behaviors of infected persons can put others at risk of infection: unprotected sex involving the exchange of bodily fluids and syringe sharing. Because HIV is not transmitted by casual contact, the simple fact that a client is infected would not give rise to a duty to warn the client's family or acquaintances who are not engaged in sex or syringe sharing with the client.

This still leaves open the question as to when duty arises. Is it when a client tells a counselor that he wants to or plans to infect others? Or when a client tells the counselor that he has already exposed others to HIV? These are two different questions.

Threat to expose others

A counselor whose client threatens to infect others should consider four questions in determining whether there is a “duty to warn”:

- 1.

Is the client making a threat or “blowing off steam?” Sometimes, wild threats are a way of expressing anger. However, for example, if the client has a history of violence or of sexually abusing others, the threat should be taken seriously.

- 2.

Is there an identifiable potential victim? Most States that impose a “duty to warn” do so only when there is an identifiable victim or class of victims. However, unless public health authorities have the power to detain someone in these circumstances there is little reason to inform them.

- 3.

Does a State statute or court decision impose a duty to warn in this particular situation?

- 4.

Even if there is no State legal requirement that the program warn an intended victim or the police, does the counselor feel a moral obligation to do so?

Clearly, there are no definitive answers in this area. Each case depends on the particular facts presented and on State law. If a provider believes she has a “duty to warn” under State law, or that there is real danger to a particular individual, she should do so in a way that complies with both the Federal confidentiality regulations and any State law or regulation regarding disclosure of medical or HIV/AIDS-related information. Because a client is unlikely to consent to disclosure to the potential victim, to comply with the Federal regulations a provider could act as follows:

- ▪

Seek a court order authorizing the disclosure. The program must take care that the court abide by the requirements of the Federal confidentiality regulations, which are discussed below in detail. It should also consult State law to determine whether it imposes additional requirements.

- ▪

Make a disclosure that does not identify the person as a client in substance abuse treatment. This can be accomplished either by making an anonymous report or, for a program that is part of a larger non-substance abuse treatment facility, by making the report in the larger facility's name. Counselors at freestanding alcohol or drug programs cannot give the name of the program. (Non-client-identifying disclosures are discussed more fully under “Exceptions that permit disclosure,” below.)

In these circumstances, the counselor should also limit the way he makes the warning to minimize the exposure of the client's identity as HIV positive.

Recounting an exposure

Suppose an HIV-infected client tells his counselor that he has had unprotected sex or shared syringes with someone. If the counselor knows who the person is, does she have a “duty to warn” that person (or law enforcement)? This is not a true duty to warn case because the exposure has already occurred. The purpose of the “warning” is not to prevent a criminal act but to notify an individual so that she can take steps to monitor health status. Thus, it is probably not helpful to call a law enforcement agency. Rather, the counselor might want to let the public health authorities know, particularly in States with mandatory partner notification laws. Public health officials can then find the person at risk and provide appropriate counseling.

How can programs notify the public health department without violating confidentiality regulations? In some areas of the country, programs have signed QSOAs with public health departments that provide services to the program. A QSOA enables providers to report exposures to the department in situations like these. The public health department can then not only help the person the counselor believes was exposed but also trace other contacts the client may have exposed. In doing so, the public health department often does not identify the person who has put his contacts at risk. The public health department would not have to tell the contact that the person is in substance abuse treatment, and the QSOA would prohibit it from doing so. (A treatment program must also make sure that reporting an exposure by a client through a QSOA complies with any State law protecting medical or HIV/AIDS-related information.)

If the provider does not have a QSOA with the public health department, it might try one of the following methods:

- ▪

Consent. The provider could inform the health department with the client's consent. The consent form must comply with both the Federal confidentiality regulations and any State requirements governing client consent to release of HIV/AIDS information, as well as any other State law governing consent (e.g., whether a parent also must consent).

- ▪

“Anonymous” notification. If the program notifies the public health department in a way that does not identify the client as a substance abuser, this constitutes complying with the Federal regulations.

- ▪

Court order. Again, State law must be consulted to determine whether it imposes requirements in addition to those imposed by the Federal regulations.

One of the above methods should enable the provider to alert the public health department, which is the most effective way to notify someone who may have been exposed.

The program should document the factors that impelled the decision to warn an individual of impending danger of exposure or to report an exposure to the public health department. If the decision is later questioned, notes made at the time of the decision could prove invaluable.

As noted earlier, whenever a program proceeds without a client's consent to warn someone of a threat the client made or to report an exposure that has already occurred, the program may be undermining the trust of other clients and thus its effectiveness. This may be particularly true for a program serving HIV-positive clients. This is not to say that a disclosure should not be made, particularly when the law requires it. It is to say that a disclosure should not be made without careful thought.

Circumstances in which a “duty to warn” or “duty to notify” arises may change over time, as scientists learn more about the virus and its transmission and as more effective treatments are developed. There is little doubt that the law also will change, as States adopt new statutes and their courts apply statutes to new situations.

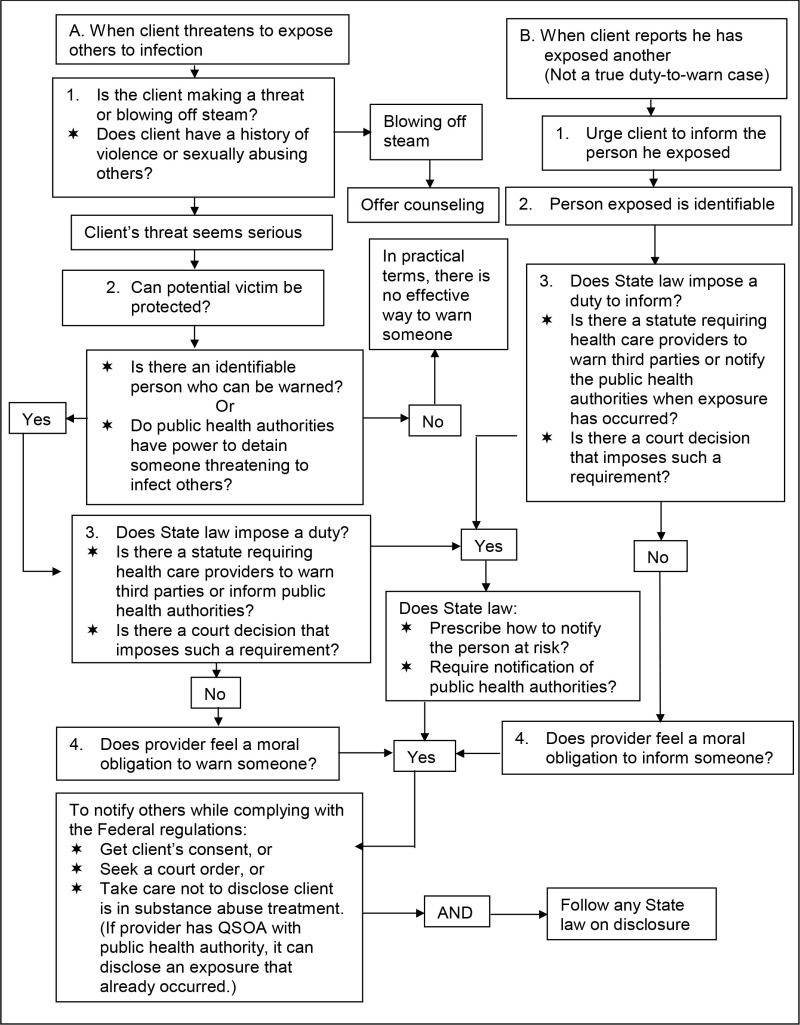

Programs should develop a protocol about “duty to warn” cases, so that staff members are not left to make decisions on their own about when and how to report threats or past occurrences of HIV transmission. Ongoing training and discussions can also assist staff in sorting out what should be done in any particular situation. Figure 9-2 provides a decision tree about the duty to warn.

Figure 9-2

Is There a Duty To Warn Clients' Sexual or Needle-Sharing Partners Of Their Possible HIV Infection?

Disclosures to insurers, HMOs, and other third-party payors

Traditional health insurance companies offering reimbursement to clients for treatment expenses require clients to sign claim forms containing language consenting to the release of information about their care. Can a program release information after a client has signed one of these standard consent forms? It cannot do so unless the form contains all the elements required by §2.31 of the regulations. Also, when the disclosure includes any HIV/AIDS-related information, the consent form must comply with State law.

Health maintenance organizations (HMOs) do not require clients to submit claim forms with language consenting to the release of information. Instead, clients in systems run by managed care organizations (MCOs) generally agree when they enter the “system” that the HMO or MCO can review records or request information about treatment at any time.

A substance abuse treatment program cannot rely on the fact that the client agreed when he signed on with the HMO that it could review his records and talk to doctors and other care providers whose fees it is covering. Federal regulations prohibit any communication unless the client has signed a proper consent form or the communication fits within another of the regulatory exceptions. State laws protecting HIV/AIDS-related information may also prohibit release of information in such circumstances.

As managed care becomes more prevalent, substance abuse treatment providers (and other professionals in the field of counseling and mental health) are finding that in order to monitor care and contain costs, third-party payors are demanding more information about clients and about the treatment provided them. The demand for information or records often comes when a provider requests authorization to continue or extend treatment. Providers are becoming all too familiar with the kinds of information they need to supply to HMOs and MCOs to obtain authorization to treat (or continue to treat) a client.

In many instances, simply getting the client's signature on a consent form that complies with the Federal rules and any State law governing the release of HIV/AIDS-related information will not resolve the ethical dilemma raised by the demand for greater and more detailed information. Providers faced with the question, “To disclose or not to disclose?” can be torn between their client's real need for continued treatment and the client's right to privacy. Should the provider disclose all information the HMO requests, perhaps shading it to ensure authorization, or should the provider protect the client's privacy, thereby jeopardizing the client's opportunity to obtain needed treatment services?

The better practice is to discuss the dilemma frankly with the client and to allow the client to decide whether and how much to disclose. To make an informed decision, the client will have to know what information the provider is being asked to disclose to obtain authorization to treat or continue treatment. The client and provider should discuss the likely consequences of the alternatives open to the client—disclosure and refusal to disclose. The client should understand that disclosure of the information the HMO seeks may be the only way to get the HMO to cover his treatment. Refusal to comply with the request for information will likely result in the HMO's refusal to cover at least some of the services the client needs.

On the other hand, the client may be more concerned that once his insurer learns she has a substance abuse problem or is HIV positive, she will lose her insurance coverage and be unable to obtain other coverage. For example, if in response to a demand from an HMO the provider releases information that the client's substance abuse has included use of both alcohol and illegal drugs, the HMO may deny benefits, arguing that since its policy does not cover treatment for abuse of drugs other than alcohol, it will not reimburse treatment when abuse of both alcohol and drugs is involved. A client whose employer is self-insured may fear being fired, demoted, or disciplined if the employer suspects he has abused substances or is HIV positive.

The process of helping the client weigh the available choices allows the client to make a decision based on his understanding of his own best interests.

Even a decision as simple as whether to submit a claim for HIV testing should be preceded by a discussion about the pros and cons of requesting coverage from an insurance company or HMO. The insurance company or HMO may infer from the fact that the client has had a test that he has engaged in risky behavior.

A client who fears the loss of employment or insurance may decide to pay for HIV testing or substance abuse treatment out of pocket. Or she may agree to a limited disclosure and ask the provider to inform her if more information is requested. If a client does not want the insurance carrier or HMO to be notified and is unable to pay for treatment, the program may refer her to a publicly funded program, if one is available. Programs should consult State law to learn whether they may refuse to admit a client who is unable to pay and who will not consent to the necessary disclosures to her insurance carrier.

Disclosing information about clients who have died or become incompetent

The Federal regulations apply to any disclosure of information that would identify a deceased client as a substance abuser, and programs may not release information unless an executor, administrator, or other personal representative appointed under State law has signed a consent form authorizing the release of information. If no such appointment has been made, the client's spouse, or if there is no spouse, any responsible member of the client's family can sign a consent form (§2.15(b)(2)). An exception is that the regulations do permit a program to disclose client-identifying information that relates to a client's cause of death pursuant to laws requiring the collection of death or other vital statistics or permitting an inquiry into the cause of death (§2.15(b)(1)).

How can programs handle disclosures about incompetent clients? If the client has been adjudicated as lacking the capacity to manage his affairs, a consent form can be signed by his guardian or other individual authorized by State law to act on his behalf. If the client has not been adjudicated incompetent but suffers from “a medical condition that prevents knowing or effective action on his own behalf,” the program director can sign a consent form but only for the purpose of getting payment for services from a third-party payor (§2.15(a)).

Exceptions that permit disclosures

The Federal confidentiality regulations' general rule prohibiting disclosure of client-identifying information has a number of exceptions. Reference has already been made to some of these exceptions: consent, disclosures that do not identify someone as a client in substance abuse treatment, disclosures pursuant to a QSOA, disclosures during a medical emergency, disclosures authorized by special court order, and disclosures of information to auditors. The rules governing these exceptions are described in the pages that follow. Also explained is another exception, not yet mentioned, that permits disclosure of information among program staff.

Communications that do not disclose client-identifying information

The Federal regulations permit programs to disclose information about a client if the program reveals no client-identifying information. “Client-identifying” information identifies someone as an alcohol or drug abuser. Thus, a program may disclose information about a client if that information does not identify her as an alcohol or drug abuser or support anyone else's identification of the client as an alcohol or drug abuser.

A program may make such a disclosure in two basic ways. First, a program can report aggregate data about its population (summary information that gives an overview of the clients served in the program) or some portion of its populations. Thus, for example, a program could tell the newspaper that in the last 6 months it screened 43 clients, 10 female and 33 male.

The second way was mentioned above: A program can communicate information about a client in a way that does not reveal the client's status as a substance abuse disorder client (§2.12(a)(i)). For example, a program that provides services to clients with other problems or illnesses as well as substance abuse may disclose information about a particular client as long as the fact that the client has a substance abuse problem is not revealed. More specifically, a program that is part of a general hospital could ask a counselor to call the police about a violent threat made by a client, as long as the counselor does not disclose that the client has a substance abuse problem or is a client of the treatment program.

Programs that provide only alcohol or drug services cannot disclose information that identifies a client under this exception—letting someone know a counselor is calling from the “Capital City Drug Program” automatically identifies the client as someone who received services from the program. However, a freestanding program can sometimes make “anonymous” disclosures, that is, disclosures that do not mention the name of the program or otherwise reveal the client's status as an alcohol or drug abuser.

Programs using this exception to disclose HIV/AIDS-related information about a client must also consult State law to determine if this kind of disclosure is permitted.

Disclosures to an outside agency that provides services to the program: QSOA

If a program routinely needs to share certain information with an outside agency that provides services to the program, it can enter into what is known as a qualified service organization agreement, or “QSOA.” This is a written agreement between a program and a person providing services to the program, in which that person

- ▪

Acknowledges that in receiving, storing, processing, or otherwise dealing with any client records from the program, she is fully bound by the Federal confidentiality regulations

- ▪

Promises that, if necessary, she will resist in judicial proceedings any efforts to obtain access to client records except as permitted by these regulations (§2.11, §2.12(c)(4))

A sample QSOA is provided in Figure 9-3. A QSOA should be used only when an agency or official outside of the program provides a service to the program itself. An example is when laboratory analyses or data processing are performed for the program by an outside agency.

Figure 9-3

Qualified Service Organization Agreement.

A QSOA is not a substitute for individual consent in other situations. Disclosures under a QSOA must be limited to information needed by others so that the program can function effectively. QSOAs may not be used between programs providing alcohol and drug services. Programs that share information with outside agencies by using the QSOA must take care that any information about HIV/AIDS or other infectious diseases is transmitted in accordance with State law.

Medical emergencies

A program may make disclosures to public or private medical personnel “who have a need for information about a client for the purpose of treating a condition which poses an immediate threat to the health” of the client or any other individual. The regulations define “medical emergency” as a situation that poses an immediate threat to health and requires immediate medical intervention (§2.51).

The medical emergency exception permits only disclosure to medical personnel. This means that this exception cannot be used as the basis for a disclosure to family, the police, or other nonmedical personnel.

Whenever a disclosure is made to cope with a medical emergency, the program must document the following information in the client's records:

- ▪

The name and affiliation of the recipient of the information

- ▪

The name of the individual making the disclosure

- ▪

The date and time of the disclosure

- ▪

The nature of the emergency

Programs using the medical emergency exception to disclose information about a client's infectious disease or infection with HIV must also consult State law to determine if a disclosure is permitted.

Disclosures authorized by court order

A State or Federal court may issue an order that will permit a program to make a disclosure about a client that would otherwise be forbidden. A court may issue one of these authorizing orders, however, only after it follows certain procedures and makes particular determinations required by the regulations. A subpoena, search warrant, or arrest warrant, even when signed by a judge, is not sufficient, standing alone, to require or even to permit a program to disclose information (§2.61).

Before a court can issue a court order authorizing a disclosure about a client, the program and any clients whose records are sought must be given notice of the application for the order and some opportunity to make an oral or written statement to the court. (However, if the information is being sought to investigate or prosecute a client for a crime, only the program need be notified (§2.65). Also, if the information is sought to investigate or prosecute the program, no prior notice at all is required (§2.66).) Generally, the application and any court order must use fictitious names for any known client, and all court proceedings in connection with the application must remain confidential unless the client requests otherwise (§2.64(a), (b), §2.65, §2.66). Before issuing an authorizing order, the court must find “good cause” for the disclosure. A court can find “good cause” only if it determines that the public interest and the need for disclosure outweigh any negative effect that the disclosure will have on the client, or the doctor-patient or counselor-client relationship, and the effectiveness of the program's treatment services. Before it may issue an order, the court must also find that other ways of obtaining the information are not available or would be ineffective (§2.64(d)). The judge may examine the records before making a decision (§2.64(c)).