NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (US). Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD). Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 58.)

Introduction

Value of Addressing FASD

Although the evidence base for effective substance abuse/mental health interventions with individuals who have or may have an FASD is limited (Premji, Benzies, Serrett, & Hayden, 2006; Paley & O'Connor, 2009), research has demonstrated that this population can and does succeed in treatment when approaches are properly modified, and that these modifications can lead to improved caregiving attitudes and reduced stress on family/caregivers as well as providers (Bertrand, 2009).

For the counselor, building competence with FASD has the obvious value of enhancing professional skills, as the counselor can provide FASD-informed care. For the client, addressing FASD has the potential to enhance the treatment experience for both the individual with an FASD and those around him or her, increase retention, lead to improved outcomes, reduce the probability of relapse (thus helping to break the cycle of repeated treatment, incarceration, displacement), and increase engagement rates in aftercare services. Access to FASD-informed interventions and accommodations, like those discussed in this chapter, has the potential to create protective factors for the client that can reduce secondary disabilities (Streissguth et al., 2004) and has been shown to lead to better outcomes (Bertrand, 2009).

For the client, addressing FASD provides an additional route to possible treatment success. Individuals with an FASD are a largely hidden population, yet these individuals frequently need services for substance abuse, and, especially, mental health (Streissguth et al., 1996). For every client that did not return for appointments, seemed noncompliant or resistant with no clear explanation of why, or just didn't seem to ‘get it,’ a knowledge of FASD could be an extra clue that helps solve that puzzle and enable success for both the client and the program.

Be Willing…

To effectively serve individuals who have or may have an FASD, what is needed most is a counselor who is willing. For many individuals with an FASD, it is not that they can't do the things necessary to succeed in treatment. Rather, it's that no one is willing to develop the understanding needed to help them succeed. While individuals with an FASD do present unique challenges, a willing counselor can make the difference between treatment success and treatment ‘failure.’

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is important to note that this TIP is not encouraging counselors to forego the primary treatment issue that brought the client to their setting in the first place, in favor of treating FASD. This chapter is only providing a process for identifying FASD as a possible barrier to successfully addressing the primary treatment issue, and making appropriate modifications to your treatment approach to maximize the potential for positive outcomes. Even if the cognitive or behavioral barriers that you identify through this process do not ultimately result in a diagnosis or positive assessment for an FASD, these are still functional impairments presenting barriers to treatment, and thus the process remains valuable.

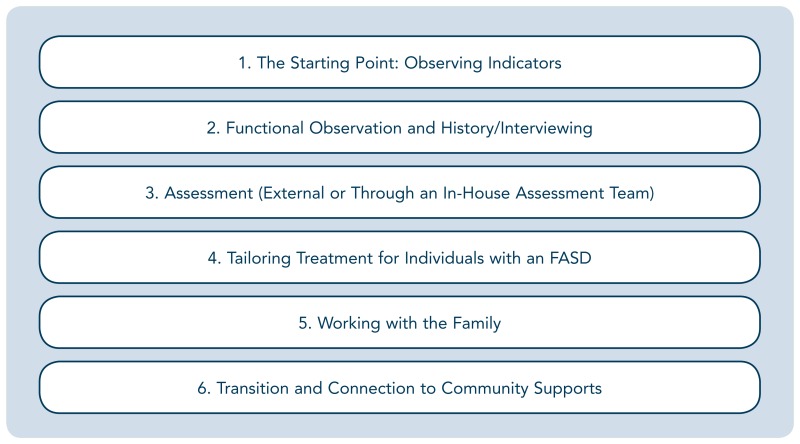

Identifying the Need for FASD Assessment, Diagnosis, and Services: Suggested Steps

The step chart on the next page illustrates a six-stage process that counselors can implement with clients for whom there are indications of an FASD. These steps will form the outline for the remainder of this chapter.

1. The Starting Point: Observing Indicators

Identifying Barriers and Causes

If there are indications of an FASD in the form of maladaptive behaviors, Step 1 represents a critical intermediate process: Be willing to consider the root cause of the behavior rather than just responding to the behavior. The easiest way to think of Steps 1 and 2 is that Step 1 is the observation of a treatment barrier or group of barriers, Step 2 is the examination of a possible root cause (or causes).

So, in Step 1, you have a client who is not doing well in treatment, and you have exhausted your normal protocol of approaches for improving the efficacy of the treatment relationship. Since individuals with an FASD are at an increased risk of having substance use or mental health issues in the first place (Streissguth et al., 1996; Astley, 2010), what this step asks you to do is take a step back and consider whether the maladaptive behaviors that you are observing (e.g., frequently missed appointments) match the profile of an individual who may have an FASD (i.e., poor time management skills, memory problems).

When working with an individual who has an FASD, a counselor would be likely to observe problem indicators in the following functional domains:

- Planning/Temporal Skills

- Behavioral Regulation/Sensory Motor Integration

- Abstract Thinking/Judgment

- Memory/Learning/Information Processing

- Spatial Skills and Spatial Memory

- Social Skills and Adaptive Behavior

- Motor/Oral Motor Control

Problems in these domains will likely show up as deficits that interfere with treatment success, including:

- Inability to remember program rules or follow multiple instructions.

- Inability to remember and keep appointments, or to get lost on the way there.

- Inability to make appropriate decisions by themselves about treatment needs and goals.

- Inability to appropriately interpret social cues from treatment professionals or other clients.

- Inability to observe appropriate boundaries, either with staff or other clients.

- Inability to attend to (and not disrupt) group activities.

- Inability to process information readily or accurately.

- Inability to ‘act one's age.’

When indicators occur in any these domains (and particularly when they occur across multiple domains), it is worthwhile to apply the FASD 4-Digit Code Caregiver Interview Checklist (Astley, 2004b) in Step 2 to determine if there is sufficient cause to 1) pursue evaluation for an FASD with this client, and 2) modify treatment to account for the client's functioning in these areas.

2. Functional Observation and History/Interviewing

An Appropriate Approach to Observation and Interviewing

If you have decided to move on to a fuller examination of the possible presence of an FASD based on indicators observed in Step 1, it is important to approach the topic with care and sensitivity. For the client, discussion of a possible FASD can cause feelings of shame, or possibly even anger or disbelief, about being identified with a “brain disorder.” For the family of the individual, particularly for a birth mother, suggesting the possible presence of an FASD can lead to feelings of guilt or a feeling of being ‘blamed,’ and a perception that service systems are unhelpful or even a negative experience. It is critical for a counselor to take a no-fault, no-shame approach to the topic of FASD, continually reassuring the individual and the family that you are examining the possibility of an FASD only as a way to achieve the best possible treatment outcome.

The FASD 4-Digit Code Caregiver Interview Checklist

The FASD 4-Digit Code Caregiver Interview Checklist provided below is from the FASD 4-Digit Diagnostic Code (Astley, 2004b). The checklist is also reproduced in Appendix D, and can be considered for reproduction and inclusion in your treatment file for clients where you believe a form of FASD may be present.

However, please note: This checklist is not presented as a validated FASD screening instrument. It is simply provided as a tool that can be used over time to note typical problem areas for someone who might have an FASD (i.e., building a profile of FASD), and provides information that you can combine with your clinical judgment to make a better-informed decision about whether to direct a client toward a more extensive FASD assessment or diagnosis.

It should also be noted that the behaviors identified on this checklist can indicate other disorders, as well. Individuals with an FASD are frequently misdiagnosed (Greenbaum et al., 2009). Given their symptoms, they may be described as meeting criteria for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), adolescent depression, or bipolar disorder. It is possible for FASD to co-occur with any of these diagnoses, but it is also possible that a condition on the fetal alcohol spectrum may better describe the pattern of target symptoms than these other diagnostic terms. A differential and comprehensive diagnosis is essential, whether in-house or through referral, and the information gathered through this checklist can help to inform a diagnostic process.

In a profile of the first 1,400 patients to receive diagnostic evaluations for an FASD at the Washington State FAS Diagnostic & Prevention Network (FAS DPN), caregivers completing an interview with a professional based in part on this checklist demonstrated an impressive ability to differentiate the behavior profiles of children with FAS/pFAS, children with severe ARND (SE/AE), and children with moderate ARND (ND/AE) (Astley, 2010).

The FASD 4-Digit Code Caregiver Interview Checklist

Severity Score: Severity of Delay/Impairment (Displayed along left margin)

Circle: 0 = Unknown, Not Assessed, Too Young 1 = Within Normal Limits 2 = Mild to Moderate 3 = Significant

| Severity | Caregiver Observations |

|---|---|

| Planning/Temporal Skills | |

| 0 1 2 3 | Needs considerable help organizing daily tasks _____________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Cannot organize time __________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Does not understand concept of time ______________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Difficulty in carrying out multi-step tasks __________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Other ______________________________________________________ |

| Behavioral Regulation/Sensory Motor Integration | |

| 0 1 2 3 | Poor management of anger/tantrums ______________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Mood swings ________________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Impulsive ___________________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Compulsive __________________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Perseverative _________________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Inattentive ___________________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Inappropriately [high or low] activity level _________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Lying/stealing ________________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Unusual [high or low] reactivity to [sound touch light] _______________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Other _______________________________________________________ |

| Abstract Thinking/Judgment | |

| 0 1 2 3 | Poor judgment ________________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Cannot be left alone ____________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Concrete, unable to think abstractly _______________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Other _______________________________________________________ |

| Memory/Learning/Information Processing | |

| 0 1 2 3 | Poor memory, inconsistent retrieval of learned information ____________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Slow to learn new skills _________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Does not seem to learn from past experiences _______________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Problems recognizing consequences of actions ______________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Problems with information processing speed and accuracy _____________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Other _______________________________________________________ |

| Spatial Skills and Spatial Memory | |

| 0 1 2 3 | Gets lost easily, has difficulty navigating from point A to point B _______ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Other _______________________________________________________ |

| Social Skills and Adaptive Behavior | |

| 0 1 2 3 | Behaves at a level notably younger than chronological age _____________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Poor social/adaptive skills _______________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Other _______________________________________________________ |

| Motor/Oral Motor Control | |

| 0 1 2 3 | Poor/delayed motor skills _______________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Poor balance _________________________________________________ |

| 0 1 2 3 | Other _______________________________________________________ |

Source: Astley SJ. Diagnostic guide for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: The 4-Digit Diagnostic Code. Third Edition. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2004. [June 1, 2012]. http://depts

.washington .edu/fasdpn/pdfs/FASD-2004-Diag-Form-08-06-04.pdf.. Used with permission from the author.

In addition, the box “Risk Assessment Questions” contains a group of questions developed at the FAS Community Resource Center in Tucson, Arizona. These questions can further assist providers seeking to determine whether an evaluation for an FASD is warranted.

3. Assessment (External or Through an In-House Assessment Team)

Assessment for the presence of an FASD is an interdisciplinary process best accomplished through a team approach. The sad reality is that the existing network of qualified assessment teams and facilities in the United States is insufficient to meet demand, and behavioral health experts have repeatedly observed the urgent need for an increase in FASD assessment, diagnosis, and treatment capacity (Institute of Health Economics, 2009; Interagency Coordinating Committee on FASD, 2011).

Risk Assessment Questions

| Yes/No | Additional Areas of Consideration |

|---|---|

| Client History | |

| Y N | Are there alcohol problems in family of origin? |

| Y N | Was the client raised by someone other than the birth mother? |

| Y N | Has the client ever been in special education classes? |

| Y N | Has the client had different home placements? |

| Y N | Has the client ever been suspended from school? |

| Y N | Has the client ever been diagnosed as ADHD? |

| How many jobs has the client had in past 2 years? ____________________________ | |

| Y N | Can the client manage money effectively? |

| Are the client's friends older or younger (for an individual with an FASD, friends tend to be younger due to lag between physical age and functional age)? _______________ |

Adapted from: Kellerman T. Recommended assessment tools for children and adults with confirmed or suspected FASD. Tucson, AZ: FAS Community Resource Center; 2005. [June 5, 2012]. http://come-over

.to/FAS/AssessmentsFASD .htm..

However, many substance abuse and mental health treatment settings may have an interdisciplinary staff team and/or sufficient referral relationships to attempt FASD assessment internally, creating an opportunity to help fill a gap in the behavioral health field. If this is the case with your agency, this section discusses some of the essential elements of FASD assessment, as well as available resources that can help your agency develop this staff capability. (The first interdisciplinary FASD diagnostic clinic [the Washington State FAS Diagnostic and Prevention Network (FAS DPN)] was established in Washington State in 1993 as part of a CDC-sponsored FASD prevention study [Clarren & Astley, 1997]. A comprehensive description of the interdisciplinary model used by the Washington State FAS DPN is presented by Clarren, Carmichael-Olson, Clarren, and Astley [2000]; see Appendix A: Bibliography). In addition, for sites that cannot provide FASD capacity internally, referral options do exist, and this section will provide information on accessing those resources.

In-House FASD Assessment: The Essential Elements

Effective in-house assessment for FASD is built on three core components: 1) building the right team, 2) accessing the right resources, and 3) gathering the right information.

Building the Right Team

FASD assessment, as will be explained below, involves gathering information and making evaluations in a variety of functional areas, and is an involved process that can overwhelm the client and his or her family. This necessitates a wide range of professional skill sets, not only to perform the various clinical and observational tasks, but also to help the client and family navigate the process smoothly. The box “In-House FASD Assessment: An Ideal Core Team” describes an ideal in-house FASD assessment team and its functions.

In-House FASD Assessment: An Ideal Core Team

| Case Coordinator |

|

|---|---|

| Psychologist1 and Speech Language Pathologist |

|

| Physical Therapist Occupational Therapist, or Vocational Rehabilitation Counselor |

|

| Physician |

|

| Family Navigator |

|

Based on TIP consensus panel recommendations and Canadian Guidelines for Diagnosis (Chudley, Conry, Cook, Loock, Rosales, & LeBlanc, 2005).

- 1

The psychologist should be trained to do neuropsychological testing.

Part 2, Chapter 2 of this TIP outlines appropriate processes if these professionals need to be added and/or accessed through referral relationships.

Accessing the Right Resources

Appendix C, Public and Professional Resources on FASD, provides information and links for accessing FASD information and training from a variety of national and regional sources.

Among these are two excellent resources for agencies seeking to develop FASD capabilities; the Washington State FAS DPN and the CDC's FASD Regional Training Centers (RTCs).

- One of the primary sites for FASD assessment and diagnosis in the United States is the Washington State FAS DPN, based at the University of Washington in Seattle. Established in 1993 through Washington State Senate Bill 5688 and support from the CDC, March of Dimes, Chavez Memorial Fund, and the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, the Washington State FAS DPN provides FASD diagnostic services as well as training in FASD. Training resources include the FASD 4-Digit Diagnostic Code Online Course and a 2-day FASD Diagnostic Team training for interdisciplinary clinical teams (or individual clinical team members) seeking to establish FASD services in their community. Visit the FAS DPN's homepage (http://depts.washington.edu/fasdpn/) to find out more about their services.

- The CDC's RTCs develop, implement, and evaluate educational curricula regarding FASD prevention, identification, and care, and incorporate the curricula into training programs at each grantee's university or college, into other schools throughout their regions, and into the credentialing requirements of professional boards. Visit the CDC's RTC homepage (http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/documents/flyerfasd_rtcs.pdf) to find out about currently funded RTC sites and available services.

Gathering the Right Information

A useful tool that your team can use to gather and organize the necessary information to support a formal FASD diagnosis is the New Patient Information Form. This form was developed by the Washington State FAS DPN and is part of the Diagnostic Guide for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: The 4-Digit Diagnostic Code (Astley, 2004b, Third Edition, pp. 103-114). If your agency decides to refer a client for an FASD diagnosis, this information will provide a necessary foundation for the diagnostic process. The New Patient Information Form can be downloaded for free from (http://depts.washington.edu/fasdpn/htmls/diagnostic-forms.htm).

In addition to basic information about the client and your agency, the New Patient Information Form provides a template for gathering information in the critical areas of Growth; Physical Appearance and Health; Neurological Issues; Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity; Mental Health Issues; School Issues; Alcohol Exposure; Information About the Patient's Biological Parents; Medical History of the Biological Family; Pregnancies of Birth Mother; Pregnancy, Labor, and Delivery of this Patient; List of Professionals Currently Involved in Patient's Care; Placements (foster, adoptive, etc.); and What to Bring to the [diagnostic] Clinic.

To further ensure collection of appropriate information and build staff knowledge and capabilities related to FASD, it will be valuable for your team to become familiar with the basic guidelines of the most widely used diagnostic approaches to the various disorders in the spectrum. A comprehensive comparison of the current FASD diagnostic systems is presented in a chapter entitled “Diagnosing FASD” (Astley, 2011), and is reprinted in Appendix E, Comparison of Current FASD Diagnostic Systems with the author's permission.

External: Assessment and Diagnosis

The reality for many programs will be that, for reasons of cost and/or lack of community resources, building an in-house FASD assessment team or diagnostic capability will be unrealistic. If this describes your agency, the FASD diagnosis and training sites discussed under Accessing the Right Resources, above, should be accessed so that you can refer your client to an appropriate provider. Agencies can also use the Resource Directory (http://www.nofas.org/resource-directory/) provided by the National Organization on FAS (NOFAS) to help locate FASD-related services.

At the same time, referral for assessment and diagnosis should be paired with treatment modifications and accommodations that are discussed in the next section. This can be done with or without a formal diagnosis of a form of FASD. If you and your clinical team have identified symptoms indicating an FASD through Steps 1 and 2 of this chapter, the methods discussed in the next section can still help the treatment process.

Many providers will not have an existing relationship with the FASD assessment or diagnosis provider to whom they refer a client. In such cases, it is vital to actively assist the client through the transition and provide regular follow-up to ensure client satisfaction and full and open communication between agencies and with the client. (Also the client's family, if they are involved in treatment.) The box “Overview of the Diagnostic Process (As Performed by the FAS DPN)” summarizes the phases of the diagnostic process as performed by the Washington State FAS DPN. The phases of this process are likely to be similar in other interdisciplinary FASD diagnostic clinics.

Overview of the Diagnostic Process (As Performed by the FAS DPN)

A comprehensive description of the FAS DPN interdisciplinary FASD diagnostic process is presented by Clarren et al. (2000).

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| Phase 1 |

|

| Phase 2 |

|

| Phase 3 |

|

Table originally appeared in Jirikowic, Gelo, & Astley (2010) with minor modifications.

When the Client Already Has a Diagnosis of an FASD

If a client has already been diagnosed with an FASD at the time of presentation to your setting, the guidelines in the next section should automatically be considered. In addition, as indicated in the table Overview of the Diagnostic Process in the previous section, the diagnosis report may also be a source of intervention and modification guidelines and should be thoroughly reviewed by the counselor with the client (and the family, if involved in the treatment process). A comprehensive summary of the types of intervention recommendations provided in relation to 120 youths following their FASD diagnostic evaluations at the Washington State FAS DPN is provided by Jirikowic et al. (2010).

At the same time, further assessment by medical, mental, and allied health professionals may still be needed to determine the client's current level of function in important areas, particularly if the diagnosis occurred years earlier. “Refreshing” the functional information will help the counselor tailor the treatment plan and counseling strategies to the client's strengths, needs, and preferences. Forms of re-testing and assessment can include the following:

- Being familiar with any medications the client is taking and observing any behaviors or physical symptoms that might indicate the need to reevaluate medication use or dosage;

- Hearing and speech tests to identify any progress in communication or barriers that may affect the client's treatment and ongoing recovery;

- Occupational therapy and physical therapy evaluations to assess the client's daily living skills and motor function, vocational skills, and preferences and possibilities;

- Determining current achievement levels in reading, spelling, and math; and

- Use of an appropriate, standardized interview or questionnaire to determine how the client compares to peers in receptive, expressive, and written communication; personal, domestic, and community daily living skills; and interpersonal relationships, play and leisure time, and coping skills.

4. Tailoring Treatment for Individuals with an FASD

Introduction

This section will discuss appropriate approaches to modifying treatment and/or making necessary accommodations for clients who exhibit indicators suggesting an FASD, or who show cognitive and behavioral barriers to treatment success, as identified in Steps 1 and 2 of this chapter.

This discussion is divided into two sections; 1) general principles for working with individuals who have or may have an FASD (regardless of age), and 2) specific considerations for adolescents who have or may have an FASD. The chapter then moves on to Step 5, Working With the Family, and Step 6, Transition and Connection to Community Supports.

As noted above, if the individual already has a diagnosis of an FASD, the diagnostic report may also include recommendations for appropriate interventions and modifications to treatment. The counselor should review this report thoroughly, if it is available.

General Principles for Working with Individuals Who Have or May Have an FASD

Safety Considerations

Safety is a primary health issue for individuals of all ages with an FASD (Jirikowic et al., 2010). Starting a treatment process without first addressing safety issues is futile and potentially dangerous: The clinician must first evaluate physical safety for the adolescent or adult with an FASD. This includes issues of violence, harm to self (such as self-mutilation) or others, victimization, adequate housing, and food. In typical adolescents and adults, psychiatric severity can be significantly reduced when co-occurring issues are treated together and mental health and substance abuse treatment are provided as an integrated program (Hser, Grella, Evans, & Huang, 2006).

For older individuals who have or may have an FASD, there are special safety considerations. This population has a number of risk factors for accidents and injury; poor decision-making, impulsivity, impaired motor coordination, working memory, attention, emotional and sensory regulation, and susceptibility to peer pressure. Even seemingly routine tasks like crossing the street safely may be impossible for those who are more severely affected. Other examples of possible safety and health concerns in adolescents and adults with an FASD are remembering medication schedules, decisions about legal and illegal substances, driving, and risk-taking situations in which poor social problem-solving (McGee, Fryer, Bjorquist, Mattson, & Riley, 2008), impulsivity, and peer pressure combine to compromise safety.

Vignette #9 in Part 1, Chapter 3 of this TIP elaborates the process of working with a caregiver to develop a personalized Safety Plan on behalf of an individual with an FASD. In addition, Appendix F, Sample Crisis/Safety Plan, contains a sample plan that has been adapted from the work of the Families Moving Forward Program (http://depts.washington.edu/fmffasd/), and can be printed and used with a client and/or their family member(s)/caregiver(s).

Risk for Abuse

Children with physical, psychological, and sensory disabilities—including FASD—are known to be more vulnerable to violence and maltreatment, or to be at a greater risk of these forms of abuse (Olivan, 2005). This vulnerability is brought about by a variety of factors, including dependence on others for intimate and routine personal care, increased exposure to a larger number of caregivers and settings, inappropriate social skills, poor judgment, inability to seek help or report abuse, and lack of strategies to defend themselves against abuse. Murphy and Elias (2006) report figures from the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect indicating that children with disabilities are sexually abused at a rate 2.2 higher than that for children without disabilities. The United States Department of Justice reports that 68 to 83 percent of women with developmental disabilities will be sexually assaulted in their lifetimes, and less than half of them will seek assistance from legal or treatment services (Pease & Frantz, 1994). In a study of 336 males and females in treatment for alcohol abuse or dependence, more than 56 percent had also experienced childhood sexual or physical abuse (Zlotnick et al., 2006).

In one long-term study, 80 percent of young adults who had experienced abuse as a child met diagnostic criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder at age 21. These individuals exhibited many problems, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and suicide attempts (Silverman, Reinherz, & Giaconia, 1996). Other psychological and emotional conditions associated with abuse and neglect include panic disorder, dissociative disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, depression, anger, posttraumatic stress disorder, and reactive attachment disorder (Teicher, 2000; De Bellis & Thomas, 2003; Springer, Sheridan, Kuo, & Carnes, 2007).

Astley (2010) has documented a high prevalence of abuse, neglect, and multiple home placements among 1,400 patients identified with an FASD—70 percent were in foster/adoptive care and had experienced, on average, three home placements. In fact, in a separate study, Astley and colleagues (2002) identified a prevalence rate of FAS in foster care that was 10-times higher—1/100—than in the general population—1/1000. Children in foster care face a risk of maltreatment, which can affect their physical health and lead to attachment disorders, compromised brain functioning, inadequate social skills, and mental health difficulties (Harden, 2004). Another study among young women with FASD found that they had poor quality of life scores and high levels of mental disorders and behavioral problems relative to standardization samples and other at-risk populations (Grant et al., 2005).

Risk for Suicide

In addition, individuals with an FASD are at significant risk of suicide at all ages studied (Huggins et al., 2008). A person with an FASD may not appear to plan or execute a suicide attempt effectively; this is not indicative of the seriousness of the intent.

High Risk of Repeated Involvement with the Legal System

People with an FASD can have specific types of brain damage that may increase engagement in criminal activity (Kodituwakku et al., 1995; Page, 2001; Mattson, Schoenfeld, & Riley, 2001; Page, 2002; Moore & Green, 2004; Clark et al., 2004; Schonfeld, Mattson, & Riley, 2005; Schonfeld, Paley, Frankel, O'Connor, 2006; Brown, Gudjonsson, & Connor, 2011). These can include:

- Lack of impulse control and trouble understanding the future consequences of current behavior;

- Trouble understanding what constitutes criminal behavior (for example, a youth with an FASD may not see any problem with driving a car he knows was stolen if he wasn't the one who stole it);

- Difficulty planning, connecting cause and effect, empathizing (particularly if the experience is not explained in a very concrete way), taking responsibility, delaying gratification, and making good judgments;

- Tendency toward explosive episodes, often triggered by sensory overload, slower rates of processing the information around them, and/or feeling “stupid;”

- Vulnerability to peer pressure and influence (e.g., may commit a crime to please friends), and high levels of suggestibility; and

- Lower level of moral maturity (due in part to social information processing deficits).

Suicide Intervention/Prevention for Individuals with an FASD

- Standard suicide assessment protocols need to be modified to accommodate neuropsychological deficits and communication impairments:

- Instead of “How does the future look to you?” ask “What are you going to do tomorrow? Next week?” (Difficulties with abstract thought.)

- The seriousness of the suicidal behavior does not necessarily equal the level of intent to die (lack of understanding of consequences).

- Obtain family/collateral input.

- Be careful about words used regarding other suicides or deaths.

- Intervene to reduce risk:

- Address basic needs and increase stability.

- Treat depression.

- Teach distraction techniques.

- Remove lethal means.

- Increase social support.

- Do not use suicide contracts (impulsivity issues).

- Monitor risk closely.

- Reinforce and build reasons for living.

- Be literal.

- Strengthen advocate-client relationship.

Source: Huggins JE, Grant T, O'Malley K, Streissguth A. Suicide attempts among adults with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: Clinical considerations. Mental Health Aspects of Developmental Disabilities. 2008;11(2):33–42.

The number of people in the criminal justice system with an FASD has not specifically been determined. Data are limited, and populations vary by state. In addition, few systems conduct any screening or can provide diagnosis. Streissguth and colleagues (2004) conducted an evaluation of 415 clinical patients with FASD at the University of Washington. Trouble with the law (including arrest, conviction, or otherwise) was reported in 14 percent of children and 60 percent of adolescents and adults with an FASD. In addition, Fast, Conry, & Loock (1999) evaluated all youth referred to a forensic psychiatric assessment for FASD in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. Of 287 youths assessed, 67 (or 23 percent) were found to have an alcohol exposure-related diagnosis. Although this result should not be generalized to the entire prison population, it does reveal a possible disproportionate representation of individuals with an FASD in the juvenile justice system.

It is important for counseling professionals to consider a client's criminal history and any factors that place the client at risk for further criminal involvement. Because persons with an FASD have problems learning from experience, they may repeat crimes and cycle through the legal system multiple times.

Clinicians may encounter individuals with an FASD who are participating in court-ordered treatment. Such individuals need help navigating the legal system. The clinician can consult with the client's attorney and assist in educating him or her about FASD. In addition, the clinician can assist in finding resources to help the client understand any legal proceedings and requirements. The National Legal Aid & Defender Association (http://www.nlada100years.org/) or the American Bar Association (www.americanbar.org) may be able to identify resources at the local level.

Vulnerability of Individuals with an FASD

Individuals with an FASD are vulnerable not only to criminal activity but also to victimization (Freunscht & Feldman, 2011). Their poor judgment may lead them to associate with people who victimize them physically, emotionally, and financially. Their impulsivity may lead them into dangerous situations. Women with an FASD may get involved with negative associations for food, shelter, attention, or drugs (Page, 2003). In addition, their impaired sense of boundaries can lead to sexual victimization. Because of their unpredictable behavior, they may need 24-hour supervision (Streissguth, 1997).

Even with compensatory strategies, the person with an FASD may be less able to use judgment, consider consequences, or understand abstract situations (Kodituwakku, 2007; Astley, 2010; Freunscht & Feldman, 2011). Impulsivity is an ongoing issue. Social isolation and loneliness may drive the person to seek out any type of friendship and lead to victimization. A discussion or pursuit of safeguards for the person may be necessary:

- Recognize that victimization may occur, and keep vigilant for situations that may arise in the person's life.

- Role-play personal safety and specific scenarios that people face (e.g., who is a stranger vs. who is a friend) to allow the individual to practice taught skills and perhaps allow them to pursue safe activities (De Vos, 2003). Consider videotaping the client doing it right in the role-play so he or she can watch it over and over, reinforcing the lesson. Watching the video also helps move the information from short-term memory to long-term memory. (In many cases, though certainly not all, long-term memory has been observed to function better than short-term memory for individuals with an FASD).

- Establish written routines and structured time charts, and have these where they are easily seen throughout the day.

- Provide a buddy system and supervision to help decrease opportunities for victimization.

- Consider a guardianship of funds to protect the individual. A trustee can ensure that the necessities of life are covered, including rent, food, clothing, and finding an advocate. The clinician may want to include such provisions in the aftercare plan.

- Help the client find a healthy, structured environment in aftercare to help them avoid criminal activity.

Family Safety and Support

For all families caring for an individual with an FASD, or when parents themselves have an FASD, establishing family safety and support is vital. A crisis/safety plan should always be put in place (see Appendix F for an example Crisis/Safety Plan form). To stay safe and well-supported, it is important to help the client (and caregivers) identify available services, determine which ones are effective for them or their children, and understand how to work productively with service providers (Streissguth, 1997). (See Appendix G for a Services and Supports Checklist that can be reviewed with clients as a worksheet.)

For birth families in recovery, the counselor can help families cope with FASD during the recovery process. This is best done by building a protective environment for clients and their children. This may include helping them obtain safe, stable housing, assisting with daily living skills (such as bill paying and food shopping), and overseeing home situations. It is also important to establish a network of community service providers who will be available for aftercare to promote ongoing recovery and avoid relapse (Millon, Millon, & Davis, 1993).

For more information about this topic, see Step 6, Transition and Connection to Community Supports).

Modifying a Treatment Plan

Factors to Consider

When modifying a treatment plan for an individual who has or may have an FASD, the following should be considered:

- Help the client adjust to a structured program or environment and develop trust in the staff. Individuals with an FASD tend to be trusting (Freunscht & Feldman, 2011) and need a great deal of structure, but may have trouble adapting to changes in routine and to new people.

- Share the rules early and often. Put instructions in writing and remind the client often. Keep the rules simple and avoid punitive measures that most individuals with an FASD will not process. If a rule is broken, remind the client of the situation and help to strategize ways they can better follow the rule in the future.

- Take a holistic approach, focusing on all aspects of the client's life, not just the substance abuse or mental health issues. Include basic living and social skills, such as how to dress, groom, practice good hygiene, present a positive attitude, and practice good manners. Help the client develop appropriate goals within the context of his or her interests and abilities.

- Provide opportunities to role-play or otherwise practice appropriate social behaviors, such as helping others. Areas of focus may include impulse control skills, dealing with difficult situations such as being teased, and problem-solving.

- In an inpatient setting, allow time for the client to be stabilized and acquire the basic skills to cooperate with others before discussing his or her substance abuse or mental health issues. In an outpatient setting, it may help to develop a rapport with the client and establish trust and communication before addressing the primary treatment issue.

- Assume the presence of co-occurring issues. It is likely that a high percentage of people with an FASD have at least one co-occurring mental disorder (O'Connor et al., 2002; Streissguth et al., 2004; Clark et al., 2004; Astley, 2010). In a study of 1,400 patients with FASD, Astley (2010) documented that 75 percent had one or more co-occurring disorders, with the most prevalent being ADHD (54 percent). In a study of 80 birth mothers of children with FAS, 96 percent had from one to nine mental disorders in addition to alcoholism (Astley et al., 2000b); the most common was phobia (76 percent). Forty-four percent of the women had mental disorders diagnosed by the age of 8 years.

- When possible, include the family or caregivers in activities, such as parent education about FASD and substance abuse and/or mental health, strategies for providing care for an individual with an FASD and a substance abuse or mental health problem (e.g., avoiding power struggles), and building the client's self-esteem. Help family and caregivers practice positive communication skills such as active listening, use of literal language, and avoiding “don't” (i.e., focusing on what needs to be done rather than what should not be done).

- Include the client in treatment planning/modification, and build family/caregiver meetings into the plan as well, with a clear purpose and agenda. Recognize that some family members may also have an FASD, and work with them accordingly.

- Incorporate multiple approaches to learning, such as auditory, visual, and tactile approaches. Avoid written exercises and instead focus on hands-on practice, role-playing, and using audio- or video-recording for playback/reinforcement of learning. Use multisensory strategies, such as drawing, painting, or music, to assist the client in expressing feelings. These strategies take advantage of skills that many individuals with an FASD have. They can also help the client share difficult feelings that may be hard to talk about, such as fear and anger.

- Consider sensory issues around lighting, equipment sounds, and unfamiliar sensations and smells. Individuals with an FASD can be very sensitive to these environmental factors.

- Arrange aftercare, and encourage family/caregivers to participate in a support group to continue to learn parenting skills and to be encouraged in the recovery process (see Step 6, Transition and Connection to Community Supports).

The Navigator

A person who has impaired vision is given a seeing eye dog. A person with impaired hearing is given an interpreter or a hearing aid. These external devices are necessary for the person with physical impairments to be able to function to maximum potential in life.

The person with an FASD has a physical impairment in the area of the brain, particularly the forebrain or frontal lobes, which regulate the executive functions. A navigator refers to the presence of another responsible person (parent, teacher, job coach, sibling) who can mentor, assist, guide, supervise, and/or support the affected person to maximize success (which may need to be redefined as the avoidance of addiction, arrest, unwanted pregnancy, homelessness, or accidental death).

Because some individuals with an FASD may appear to be bright and normal, the disability that is brain damage may only be apparent in test results, or in actions that place the person at serious risk. It is the risk of danger to the person and to others that makes a navigator such a useful and important concept. A navigator can seem like a form of enabling or an encouragement of co-dependency. More accurately, however, a navigator is an appropriate form of advocacy to ensure that the individual receives whatever assistive devices are needed for him or her to participate in life in as normal a capacity as reasonably possible.

For many individuals with an FASD, the navigator can be someone with whom they “check in” on a regular basis, or vice versa. For others, the navigator will play a more constant advocacy role, and may share the role with others. (See Vignette #9 for an example of a father playing the role of a navigator, and sharing the role with a coach and one of his son's relatives.)

Adapted from: Kellerman T. External brain. 2003. [June 5, 2012]. http://come-over.to/FAS/externalbrain.htm..

Counseling Strategies

Due to the cognitive, social, and emotional deficits seen in FASD, counseling clients with these conditions requires adaptability and flexibility. Research data, clinical observation, and caregiver reports all suggest that it is crucial to tailor treatment approaches. Traditional approaches may not prove optimally effective, and more effort may be needed to convey basic concepts and promote a positive therapeutic relationship and environment. The following are recommendations designed to help providers:

- Set appropriate boundaries;

- Be aware of the client's strengths;

- Understand the impact of any abuse the client has experienced;

- Help the client cope with loss;

- Address any negative self-perception associated with an FASD;

- Focus on self-esteem and personal issues;

- Address resistance, denial, and acceptance;

- Weigh individual vs. group counseling;

- Consider a mentor approach; and

- Assess comprehension on an ongoing basis.

Boundaries

Establishing a trusting and honest relationship while maintaining boundaries is important with any client. Because persons with an FASD often lack social skills and have social communication problems (Kodituwakku, 2007; Greenbaum et al., 2009; Greenspan, 2009; Olson & Montague, 2011), they may breach boundaries by making inappropriate comments, asking inappropriate questions, or touching the counselor inappropriately. To set boundaries, it may help to have the client walk through the rules and expectations and demonstrate expected behavior. Frequent role-playing can help the client learn to apply concepts and figure out how to respond to various situations.

Persons with an FASD frequently experience difficulty with memory (Rasmussen, 2005; Riggins et al., 2012). Added to this, they may be able to repeat rules but not truly understand them or be able to operationalize them. Thus, it is important to review rules regularly. It is much more effective to limit the number of rules, review them repeatedly, and role-play different situations in which the person will need to recall the rules. Repetition is key.

Strengths

Many people focus on the deficits in persons with an FASD, but they also have many strengths. Some of these can be used in the treatment setting as part of counseling. Family may be a strength area: Parents report their children with FASD were engaged with their families and willing to receive—and even seek—help (Olson et al., 2009), as well as demonstrating a willingness to provide assistance with ordinary tasks (Jirikowic et al, 2008). Based on extensive clinical experience, Malbin (1993) identifies a number of other strength areas. For example, some people with an FASD are quite creative. They can express themselves through art and music, which may prove more effective than traditional talk therapy. Other approaches may involve storytelling and writing. These techniques can also be used for practical matters, such as developing a poster with treatment goals. In addition, visual aids can assist by drawing on areas of relative strength, so drawn or pictured goals may aid recall better than a written or spoken list of instructions.

History of Abuse

Given the risk of abuse among persons with an FASD and among individuals with substance abuse and/or mental health issues, it is likely that a client with a combination of these will have some personal abuse history (Astley et al, 2000b). The counselor working with persons with an FASD needs to be sensitive to the possibility of childhood abuse and other forms of victimization, and their impact on the counselor–client relationship. A common theme that counselors need to be attentive to is powerlessness, a theme often reflected in the following types of client communications and behaviors:

- Clients undervaluing their own competencies.

- Clients viewing others' needs and goals as more important than their own.

- Clients' inability to obtain nurturance and support for themselves.

- Clients' feelings of depression, anger, and frustration about their lives.

- Clients' low expectations for their own success.

Loss and Grieving

All individuals with an FASD have experienced losses in their lives. The fact that they are not like their peers is a loss of the ability to be like everyone else. Some have lost the hopes and dreams of what they wanted to be. Others lose their family or a secure future.

Some lose the opportunity for meaningful peer relationships and friendships. These losses can affect people in many ways and need to be addressed. The counselor can help to address these areas of loss through a number of strategies:

- Use active listening strategies, such as repeating what the person has said;

- Be honest;

- Raise awareness of experiences of separation and loss;

- Acknowledge and validate losses experienced;

- Acknowledge the client's feelings about loss;

- Avoid “good parent/bad parent” issues;

- Encourage communication; and

- Refer for further treatment (e.g., mental health) when necessary.

Self-Perception

Self-perception is a major issue with FASD. Despite the advent of the disease model, many people still view alcohol problems as a sign of moral weakness or a character flaw. This negative stereotype can be particularly severe in relation to pregnant women who drink, making the topic difficult to discuss (Salmon, 2008). Added to this, the negative judgment toward the mother may also be visited on the child. A counselor needs to be aware of this, and approach the issue carefully and sensitively if he or she suspects a client has an FASD.

Given their cognitive, social, and emotional deficits, persons with an FASD may think they are powerless to change. It is important to work through this issue with the client. They need to understand that they are not responsible for their disability and that they deserve respect. They also need to know that change is possible.

Self-Esteem and Personal Issues

The combination of abuse, loss, grief, and negative stereotypes can lead to self-esteem issues in any individual. Self-esteem is regularly an issue for individuals with an FASD (Olson, O'Connor, & Fitzgerald, 2001). Those who also have substance abuse or mental health problems face a double-edged sword: Their self-esteem can be damaged by their experience with an FASD and by their substance abuse or mental health issue. The clinician can use several strategies to help address self-esteem and personal issues:

- Use person-first language. An FASD may be part of who a person is, but it is not the person's entire identity. Someone can have an FASD, but nobody is an FASD.

- Do not isolate the person. Sending persons with an FASD out of the room to think about what they have done or responding to issues in a group session by simply ejecting them will often increase their sense of isolation and does not help them learn appropriate behaviors.

- Do not blame people for what they cannot do. Demanding that people repeatedly try to do things they cannot do is a lesson in frustration. It is important to have patience and understand individual limitations. People with an FASD may need something repeated several times because they have trouble remembering, not because they refuse to pay attention.

- Set the person up to succeed. Measures of success need to be different for different people. It is important to identify what would be a measure of success for the individual with an FASD and reinforce successes in concrete terms (e.g., “You did a great job of being on time for our session today. Thank you.”) Training in social skills, anger management skills, and relaxation skills can help. In order for skills-building programs to be most successful for the person with an FASD, they need to be repeated periodically.

Resistance, Denial, and Acceptance

Individuals who have or may have an FASD may deny that they have a disability. Although some are relieved to know the cause of their difficulties, others may struggle to confront or accept their situation. The counselor needs to take time to help the person cope with the lack of understanding that often surrounds FASD. Women with an FASD, for instance, may fear becoming like their mothers and having a child with an FASD. An individual with an FASD may have difficulty with forgiveness of the birth mother, or may feel that it is inevitable that they will pass on FASD to their children. Counselors should reassure clients that they are not responsible for their disability, help them resolve their feelings about the birth mother, and educate them about the science of their condition (i.e., that it is not inevitable that they would pass on the condition). This process may take awhile, and the person may drift back and forth from accepting the disability to denying it. Exploring the reasons for the denial and understanding the client's fears can help.

Individual Counseling vs. Group Sessions

Individuals with an FASD may struggle to function in a group setting. Studies have shown increased levels of sensory sensitivities in this group, at least for children (Jirikowic et al., 2008). Clinical observations suggest individuals with an FASD can become overwhelmed by sensory input from large groups, noise, small spaces that cause crowding and touching of others, and visual distractions. Given the executive function deficits that are common in this clinical population, individuals with an FASD may not be able to process everything in the discussion and become lost. They may also ‘talk too much,’ and/or not be able to effectively convey their feelings and ideas in group discussions.

Individual counseling may be needed to avoid some of the issues that arise in clients with an FASD who lack social skills and find group settings confusing or overwhelming. Talk therapy can be modified to incorporate role-playing, practice dialogues, play therapy, art therapy, and other methods that can draw on the strengths seen in individuals with an FASD. Printed material may be helpful, but should be written in simple language with a clear, non-distracting page layout.

If group work is necessary, the counselor can assist the client who has or may have an FASD by making some accommodations:

- Explain group expectations concretely and repeat these ideas often.

- If a person monopolizes conversation or interrupts, use a talking stick as a concrete visual reminder of who should be speaking. Hand the stick to the person whose turn it is to speak and pass the stick to others as appropriate.

- Give the person time to work through material concretely within the group time so he or she can ask questions or you can check understanding of material. The client may need extra time to process information. Listen for key themes to emerge slowly through the person's talk and behaviors.

- Allow the client to get up and walk around if he or she gets restless.

- Use concrete representations, such as marking the floor, to show the concept of boundaries.

- Make adaptations for the whole group to avoid singling out the client.

Use of a Mentor

Programs that work with individuals with an FASD have found that mentoring can be effective, as it provides a consistent, stable, one-to-one relationship and allows for the development of a personal bond with a trained individual who has knowledge and experience working with those who have an FASD (Malbin, 1993; Schmucker, 1997; Grant et al., 2004; Denys, Rasmussen, & Henneveld, 2011). A mentor can:

- Assist with the development of concrete and consistent rules and goals that will guide behaviors in specific situations;

- Improve comprehension in discussions with others (e.g., providers or other clients); and

- Assist with the development of personal scenarios for the adult to work out responses and practice through role-play

Ongoing Assessment for Comprehension of Information

Extensive clinical observations reveal that individuals with an FASD may appear to understand when they do not. Parents often say their family member with an FASD “just doesn't get it.” This means that individuals with an FASD may repeat information without actually understanding the content, and so will be unlikely to follow through. Because of this, it is important to provide consistency and re-check the retention of information often:

- Ask the client to summarize what you have said.

- Review written material, such as rules, at each session.

- Do not assume that the client is familiar with a concept or can apply it simply because you have reviewed it multiple times; have discussions that explore their understanding beyond simply being able to repeat the concept.

Clinical wisdom holds that the only consistent thing about FASD is that those who are affected behave inconsistently. This means, for example, that a client may demonstrate that they know something on Monday, but have trouble recalling that same information on Tuesday. The clinician can benefit by following the rule to: REPEAT, REPEAT, REPEAT.

Sexual Abstinence, Contraception, and Pregnancy

Adolescents and adults with an FASD should be well informed and consulted about decisions regarding abstinence, contraception, and pregnancy. There are many ways to support pregnancy, delivery, and parenting by an individual with an FASD. The client may have questions about whether or not the FASD can be passed on to any offspring; caregivers must clarify that only prenatal exposure to alcohol can cause an FASD. If the client has children, the parenting skills taught to the client should account for the possible presence of an FASD in both parent and child; the skills learned must be appropriate to each of them and work for each of them.

Clinical experience reveals that women with an FASD can be vulnerable to exploitation and unintended pregnancy (Grant et al., 2004; Merrick, Merrick, Morad, & Kandel, 2006). It can be difficult for them to use contraception effectively due to memory lapses, problems following instructions, or difficulty negotiating contraceptive use with a partner. Counselors can help clients evaluate their family planning needs and assist in obtaining reliable, long-term birth control methods.

Although it may be unusual in a treatment setting, very practical and basic assistance may be important for a woman with an FASD. The counselor may need to accompany the client to a doctor's appointment to help her understand her options and choose the best one. One study found improved use of contraception among young women with an FASD by implementing a community intervention model of targeted education and collaboration with key service providers, and by using paraprofessional advocate case managers as facilitators (Grant et al., 2004).

Clinical consensus based on evaluation of common behavioral characteristics of FASD suggests that the causal relationship between HIV/STDs/viral hepatitis and substance use disorders may be heightened among those who also have an FASD. Care plans for individuals with an FASD entering substance abuse treatment should include communicable disease assessment.

Medication Assessment

In some cases, medication options may be appropriate to treat some of the functional or mental health components of FASD (Coe, Sidders, Riley, Waltermire, & Hagerman, 2001). The counselor may want to refer the client for an assessment to determine whether he or she can follow a regimen of taking a pill every day or getting a shot every few months. It is also important to consider the possible physical impact, since persons with an FASD may have health problems and be prone to side effects. Medications for individuals with an FASD may not work at rates similar to other populations and/or may require different dosages to work (O'Malley & Hagerman, 1999). Including a mentor or supportive family member in the discussion may help the individual with an FASD to be more comfortable asking questions and better understand what is being said.

Job Coaching

In a study of 90 adults with a diagnosed form of FASD, most had some work experience but the average duration was only 9 months (Streissguth et al., 1996). Some of the general barriers to successful work for people with disabilities are external; discrimination by employers, co-workers, and family, transportation issues, completing applications and job testing, social skills, and the lack of support at interviews. Other barriers are internal, and need to be addressed early on in the vocational process; self-esteem and self-worth, fear of success, self-sabotage, and having a realistic view of strengths and career goals. All of these internal factors affect career choice, self-presentation at the interview and the job, and ultimate vocational success (Fabian, Ethridge, & Beveridge, 2009; Leon & Matthews, 2010). These issues should be addressed through counseling and skills-building prior to standard vocational tasks.

A job coach or vocational rehabilitation counselor may need to remain involved with an individual with an FASD beyond the time when he or she seems to “know” the job, and be understanding if the individual has days or situations in which he or she can't remember what to do or gets overwhelmed. Individuals with an FASD may do well enough on a job that a coach or counselor decides they “get it” and stops providing support, when in fact it was the support that enabled success.

Vocational Rehabilitation

Vocational Rehabilitation should be viewed as an interdisciplinary team process. It may be up to a parent or caregiver to coordinate information. The team may include a physician for medical and health issues, an occupational/physical therapist, a psychologist for counseling to address some of the above issues, teachers, case managers, and job placement agencies (Gobelet, Luthi, Al-Khodairy, & Chamberlain, 2007). Some adults and families will choose sheltered workshops because of concerns about safety, transportation, long-term placement, work hours, maintaining disability benefits, social environment, and work skills issues (Migliore, Grossi, Mank, & Rogan, 2008). At the same time, the majority of adults with an intellectual disability prefer integrated employment over sheltered workshops, regardless of disability severity (Migliore, Grossi, Mank, & Rogan, 2007).

Special Considerations for Adolescents Who Have or May Have an FASD

It is important to remember that adolescents are quite different from adults, and adolescents with an FASD differ from teens that develop in typical fashion. Adolescents with an FASD may function at social and emotional levels well below their chronological age, with an uneven cognitive and physical profile (some skills less impaired than others). The treatment process must incorporate the nuances of the adolescent's experience. In modifying treatment plans for adolescents with an FASD, it is important to consider cognitive, emotional, and social limitations, as well as risk factors that led to their substance abuse or mental health issue. Many youth with an FASD have grown up in less-than-ideal environments, facing parental substance abuse, economic deprivation, abuse, and multiple foster care placements. These situations can increase their risks for substance abuse and mental disorders.

A summary of clinical and empirical evidence shows that adolescents will commonly exhibit learning and behavior challenges, especially in adaptive function (getting along from day to day), and in remaining organized and regulated (Streissguth et al., 2004; Spohr, Willms, & Steinhausen, 2007). They often learn information slowly (especially what is said to them), tend to forget things they have recently learned, and make the same mistakes over and over. They can often have trouble shifting attention from one task to another. Like those with ADHD, they may be impulsive and find it hard to inhibit responses, and may be restless or even obviously hyperactive. In general, they may have trouble regulating their behavior. Even though adolescents with FASD may be talkative, they have social communication problems (such as leaving out important details or explaining things in a vague way). Adolescents with FASD tend to show poor judgment, are suggestible (and therefore easily influenced by others), and show immature social skills. Because of this, they may be too friendly with people they do not know well, too trusting, and have difficulty recognizing dangerous situations.

Treatment Tips From the Field

In addition to the guidance provided in this chapter, providers in British Columbia provided the following anecdotal suggestions for effective programming for individuals who have or may have an FASD.

| Treatment Planning |

|

|---|---|

| Assisting Navigation and Success |

|

| Language |

|

Source: Rutman D. Substance using women with FASD and FASD prevention: Service providers' perspectives on promising approaches in substance use treatment and care for women with FASD. Victoria, British Columbia: University of Victoria; 2011. .

Treatment Plan Modification

It is generally believed that traditional forms of therapy, such as “talk therapy,” are not the most effective choice when working with adolescents with an FASD. Their cognitive deficits prevent them from developing insight or applying lessons to their real lives. However, with creativity and flexibility, a treatment plan can be developed that includes techniques counselors are familiar with and comfortable with, adapted to fit the needs of the client (Baxter, 2000).

Adolescent Development Issues in FASD

The following table outlines some of the more common developmental delays and deficits experienced by individuals with an FASD through the adolescent years (ages 12–21), and useful treatment approaches. This table is based on an expert clinical consensus.

| Normal Development | FASD | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Range: 12-21 | Ability to evaluate own behavior in relationship to the future | Lack of connection between thoughts, feelings, and actions | Repeated skills training with role-playing and videotaping; videotaping of person's behavior |

| Understanding consequences of behavior | |||

| Importance of peer group | Difficulty resisting negative peer influences | Connect person with pro-social peers, mentors, and coaches | |

| Development of intimate relationships | Difficulty with accurately interpreting social cues (e.g., words, actions, nonverbal cues) | Social skills training; repeated discussions of sexuality and intimacy as appropriate | |

Addressing Peer Influences

Clinical observations indicate that adolescents with FASD are socially immature, and research documents that adults with FASD are more suggestible (Brown et al., 2011). Developmental literature makes clear that peer influences are important in the adolescent stage, and that deviant peer influences can lead to antisocial behavior. The counselor should address issues such as peer pressure in treatment to set the stage for less risky behavior outside treatment. Linking an adolescent with an FASD with a mentor is a sound treatment strategy.

Ongoing Assessment for Comprehension of Information

As with adults, it is important to check often to make sure the adolescent client understands what has been said. Ask the client to summarize what you have said. Review written material, such as rules, at each session. Repeat, repeat, repeat, even if the client says, “You've told me this a hundred times.”

For adolescents, applying concepts can be difficult. Cognitive deficits, the frustration of having an FASD, and typical teen rebellion can make communication especially hard. Role-playing different situations, providing opportunities to share and process feelings, and giving the client time to process information is important. It also may help to use alternative methods of expression, such as drawing, to assist the client in sharing his or her understanding.

Educational Support (IDEA and FAPE)

The Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) entitles every young person to a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment. If the client is eligible, this can continue until age 21. If you have a client who has or may have an FASD and is in school, it is important to consult with the school regarding any provisions in that client's individualized education plan (IEP), either those identified by the school that should be carried over to treatment or vice versa. In a study of 120 children undergoing FASD diagnosis at a Washington State FAS DPN clinic, Jirikowic and colleagues (2010) found that over 90 percent did require intervention recommendations associated with their educational plan.

In the outpatient setting and during aftercare, it is a good idea for the psychologist to consult with the school counselor or case manager (if the client has one) regarding educational needs. Areas such as social skills may be addressed in the IEP, and are important to address during treatment and as part of aftercare. It also helps to be aware of any academic issues that may affect the client's treatment, such as stress about academic performance or difficulties with classmates.

Parents may not be aware of the laws regarding education of children with disabilities and may feel overwhelmed. They may be having problems dealing with their child's school and wonder what to do. The counselor can help by informing the client and family about IDEA and FAPE requirements and helping outline possible interventions to suggest to the school.

The U.S. Department of Education provides an online overview (http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/edlite-FAPE504.html) of the stipulations of FAPE and who qualifies for educational support under its terms.

In addition, vignette #10 in Part 1, Chapter 3 of this TIP discusses some of the key aspects of developing an IEP for an individual who has an FASD.

Psychosexual Development

Early and ongoing social experiences play a key role in psychosexual development. Adolescent tasks include having and maintaining intimate relationships, managing complex emotions and social situations, and developing independent thinking. The adolescent with an FASD may not achieve these milestones all at the same time, at the usual age range, or at all. Many adolescents with disabilities are delayed or prevented from achieving these goals by social isolation or a variety of functional limitations. Social skills may be broken down into manageable tasks, just as in every other area of instruction. This includes the basics first, such as mastering appropriate greetings, eye contact, body language, personal space, self-advocacy skills, and telephone and computer skills. A foundation in some or all of these basic skills will allow for the development of more complex skills. Mentors and peers may be very effective in this regard.

Vocational Coaching

Young adults with a disability need advocacy and support with a variety of new agencies and support services throughout the transition and adult years. A life skills curriculum should include how to use the internet to search for employment and employment enhancement services, awareness of issues associated with safe work environments, interviewing strategies, appropriate use of medication, managing finances, dealing with workplace routines and expectations, being cautious about at-risk situations, and knowing when to ask for help (Winn & Hay, 2009). Role-playing each of these skills with the client will be beneficial.

Counselor Self-Assessment

Working with clients with an FASD can raise issues for you, the counselor. You might feel resentment about being “stuck” with such challenging clients, or harbor negative attitudes toward women who drink while pregnant. The client with an FASD can trigger feelings of guilt and shame in a counselor who drank while pregnant or has a child with an FASD.

Understanding how to cope with clients with an FASD can help the counseling professional serve such clients more effectively. Olson and colleagues (2009) have underlined the importance of the need to Reframe, Accommodate, and Have Hope for caregivers raising those with FASD. These same strategies can help counselors, and are combined with the recommendations of Malbin (1993) and Schmucker (1997) to create the following recommendations for counselors providing FASD-related services.

REFRAME

Reframe your perception of the person's behavior. He or she is not trying to make you mad or cause trouble. He or she has brain damage and may have a history of abuse or other family dysfunction. You need to explore behaviors, stay patient, and tolerate ambiguity.

- Understand that FASD involves permanent brain changes.

- The client is not refusing to do things. He or she can't do them or does not understand what you are asking him or her to do.

- Clients often are not lying purposely. They are trying to fill in gaps in memory with their own information.

- Perseverating behaviors are an attempt to control or make sense of their own world.

- Transition and change are very difficult for the person with an FASD. Acting out when things change may be a reaction to fear of transitions or difficulty processing change.

ACCOMMODATE

- Expect to repeat things many times in many ways. Clients with an FASD may ask the same question every time you see them. Remember that these clients have cognitive deficits. They are not asking just to test your patience. Be patient and avoid looking bored going over the same information multiple times.

- Use a written journal or goal sheets to remind people how far they've come and where they are headed. Due to their memory difficulties, clients with an FASD will not always remember what supports or programs have been developed with them or their goals. Keep a positive attitude and focus on what the person has accomplished, rather than on goals yet to be met.

- Realize that there is no set approach; what works one time may not work the next. As part of the dysfunction of FASD, the client may experience things differently day to day or even hour to hour, and variability is the norm. Keep an open mind and be flexible. Avoid statements such as “But it worked last time.”

HAVE HOPE

- Be good to yourself. Even with a realistic plan and an established routine, nothing is perfect. Things change and setbacks occur. By expecting bumps in the road of a person's journey through life, we can learn to not take these dips personally. By offering the person with an FASD nonjudgmental and informed support, we offer hope.

- Know yourself, and take the time to reflect on your comfort level in dealing with issues surrounding FASD. Gain knowledge if needed. Gain comfort in tackling the subject by role-playing with colleagues. Know your limits and get outside help or referrals as required. Plan to connect to appropriate community resources.

Thinking Ahead and Planning for the Future

It is important to think ahead and plan for the future with adolescents and young adults with FASD. If they are able to build an independent life, counselors can help the client learn how to self-advocate and self-monitor, and should communicate these skills to the client's caregivers, as well. It is important to think ahead about education on topics such as (1) safe sex; (2) communicating clearly with partners about consensual activity; (3) use of cigarettes and alcohol; (4) use of illicit substances, such as marijuana and drugs; (5) the consequences of criminal activity; and (6) ideas of what to safely do when the individuals goes through times of feeling irritable and negative (calming strategies).

5. Working with the Family

Introduction

Multiple studies have spoken to the value of involving the family in the treatment of an individual who has or may have an FASD, if possible (Schmucker, 1997; Grant, Ernst, Streissguth, & Porter, 1997; Olson et al., 2009; Olson, Rudo-Stern, & Gendler, 2011). Involving the family in planning, choosing, and shaping services for the client has become a key intervention concept in the field of developmental disabilities, as greater family involvement has been linked to better outcomes (Neely-Barnes, Graff, Marcenko, & Weber, 2008). Family-centered care is also strongly advocated for individuals with co-occurring mental health issues and a developmental disability like an FASD (McGinty, Worthington, & Dennison, 2008).

As with many clients in substance abuse and mental health settings, it is advisable to take a broad view of family. Many individuals with an FASD will have resided with foster parents and/or in kinship care (foster and adoptive scenarios being the most common), and care scenarios may extend well beyond the more typical ages of independence, like 18 or 21. Ultimately, who the client chooses to see as family or as the important caregiver in their life should be incorporated into the process, if possible.