NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). Improving Cultural Competence. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 59.)

Gil, a 40-year-old Mexican American man, lives in an upper middle class neighborhood. He has been married for more than 15 years to his high school sweetheart, a White American woman, and they have two children. Gil owns a fleet of street-sweeping trucks—a business started by his father-in-law that Gil has expanded considerably. Of late, Gil has been spending more time at work. He has also been drinking more than usual and dabbling in illicit drugs. As his drinking has increased, tensions between Gil and his wife have escalated. From Gil's perspective and that of some family members and friends, Gil is just a hard-working guy who deserves to have a beer as a reward for a hard day's work. Many people in his Mexican American community do not consider Gil's low-level daily drinking a problem, especially because he drinks primarily at home.

Recently, Gil had an accident while working on one of his trucks. The treating physician identified alcohol abuse as one of several health problems and referred him to a substance abuse treatment center. Gil attended, but argued all the while that he was not a borracho (drunkard) and did not need treatment. He distrusted the counselors, stating that seeking help from professionals for a mental disorder was something that only gabachos (Whites) did. Gil was proud of his capacity to “hold his liquor” and felt anger and hostility toward those who encouraged him to reduce his drinking. Gil's feelings and attitudes were valid; they stemmed from and were influenced by the Mexican American culture and community in which he had been raised from infancy. Gil dropped out of treatment. When his wife threatened to divorce him if he did not take immediate action to deal with his drinking problem, he reluctantly enrolled in an outpatient treatment program. Gil, like all people, is a product of his environment—an environment that has provided him with a rich cultural and spiritual background, a strong male identity, a deep attachment to family and community, a strong work ethic, and a sense of pride in being able to support his family. In many Mexican American cultural groups, illness disrupts family life, work, and the ability to earn a living. Illness has psychological costs as well, including threats to a man's self-identity and sense of manhood (Sobralske 2006). Given this background, Gil would understandably be reluctant to enter treatment, to accept the fact that his drinking was a problem or an illness, and to jeopardize his ability to care for his family and his company. A culturally competent counselor would recognize, legitimize, and validate Gil's reluctance to enter and continue in treatment. In an ideal situation, the treatment counselor would have experience working with people with similar backgrounds and beliefs, and the treatment program would be structured to change Gil's behavior and attitudes in a manner that was in keeping with his culture and community. His initial treatment might have succeeded if the counselor had been culturally competent and the treatment program had been culturally responsive.

Like Gil, all clients enter treatment carrying beliefs, attitudes, conflicts, and problems shaped by their cultural roots as well as their present-day realities. As with Gil, many clients enter treatment with some reluctance and denial. Research shows that if clients such as Gil are greeted by a culturally competent counselor, they are more likely to respond positively to treatment (Damashek et al. 2012; Griner and Smith 2006; Kopelowicz et al. 2012; Whaley and Davis 2007). The presence of counselors of any race or gender who are culturally competent in responding to the needs and issues of their clients can greatly assist client recovery. Gaining regard, respect, and trust from clients is crucial for successful counseling outcomes (Ackerman and Hilsenroth 2003; Sue and Sue 2003a).

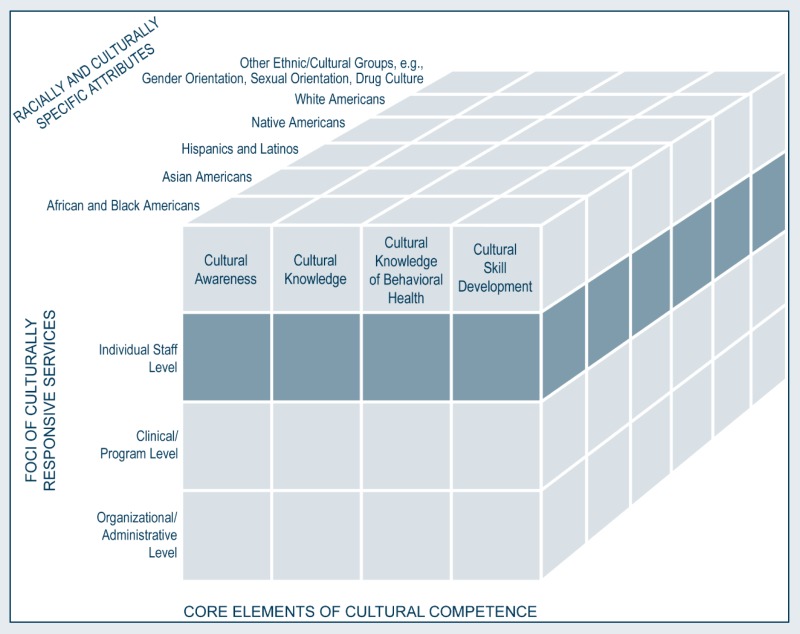

Effective therapy is an ongoing process of building relational bridges that engender trust and confidence. Sensitivity to the client's cultural and personal perspectives, genuine empathy, warmth, humility, respect, and acceptance are the tenets of all sound therapy. This chapter expands on these concepts and provides a general overview of the core competencies needed so that counselors may provide effective treatment to diverse racial and ethnic groups. Using Sue's (2001) multidimensional model for developing cultural competence, the content focuses on the counselor's need to engage in and develop cultural awareness; cultural knowledge in general; and culturally specific skills and knowledge of wellness, mental illness, substance use, treatments, and skill development.

Core Counselor Competencies

Since Sue et al. introduced the phrase “multicultural counseling competencies” in 1992, researchers and academics have elaborated on the core skill sets that enable counselors to work with diverse populations (American Psychological Association [APA] 2002; Council of National Psychological Associations for the Advancement of Ethnic Minority Interests 2009; Pack-Brown and Williams 2003; Tseng and Streltzer 2004). Cultural competence has evolved into more than a discrete skill set or knowledge base; it also requires ongoing self-evaluation on the part of the practitioner. Culturally competent counselors are aware of their own cultural groups and of their values, assumptions, and biases regarding other cultural groups. Moreover, culturally competent counselors strive to understand how these factors affect their ability to provide culturally effective services to clients.

Given the complex definition of culture and the fact that racially and ethnically diverse clients represent a growing portion of the client population, the need to update and expand guidelines for cultural competence is increasing. The consensus panel thus adapted existing guidelines from the Association of Multicultural Counseling for culturally responsive behavioral health services; some of their key suggestions for counselors and other clinical staff are outlined in this chapter.

Self-Knowledge

Counselors with a strong belief in evidence-based treatment methods can find it hard to relate to clients who prefer traditional healing methods. Conversely, counselors with strong trust in traditional healers and culturally accepted methods can fail to understand clients who seek scientific explanations of, and solutions to, their substance abuse and mental health problems. To become culturally competent, counselors should begin by exploring their own cultural heritage and identifying how it shapes their perceptions of normality, abnormality, and the counseling process.

Counselors who understand themselves and their own cultural groups and perceptions are better equipped to respect clients with diverse belief systems. In gaining an awareness of their cultures, attitudes, beliefs, and assumptions through self-examination, training, and clinical supervision, counselors should consider the factors described in the following sections.

Cultural awareness

Counselors who are aware of their own cultural backgrounds are more likely to acknowledge and explore how culture affects their client–counselor relationships. Without cultural awareness, counselors may provide counseling that ignores or does not address obvious issues that specifically relate to race, ethnic heritage, and culture. Lack of awareness can discount the importance of how counselors' cultural backgrounds—including beliefs, values, and attitudes—influence their initial and diagnostic impressions of clients. Without cultural awareness, counselors can unwittingly use their own cultural experiences as a template to prejudge and assess client experiences and clinical presentations. They may struggle to see the cultural uniqueness of each client, assuming that they understand the client's life experiences and background better than they really do. With cultural awareness, counselors examine how their own beliefs, experiences, and biases affect their definitions of normal and abnormal behavior. By valuing this awareness, counselors are more likely to take the time to understand the client's cultural groups and their role in the therapeutic process, the client's relationships, and his or her substance-related and other presenting clinical problems. Cultural awareness is the first step toward becoming a culturally competent counselor.

Racial, ethnic, and cultural identities

A key step in attaining cultural competence is for counselors to become aware of their own racial, ethnic, and cultural identities. Although the constructs of these identities are complex and difficult to define briefly, what follows is an overview. Racial identity “refers to a sense of group or collective identity based on one's perception that he or she shares a common heritage with a particular racial group” (Helms 1990, p. 3). Ethnic and cultural identity is “often the frame in which individuals identify consciously or unconsciously with those with whom they feel a common bond because of similar traditions, behaviors, values, and beliefs” (Chavez and Guido-DiBrito 1999, p. 41). Culture includes, but is not limited to, spirituality and religion, rituals and rites of passage, language, dietary habits (e.g., attitudes toward food/food preparation, symbolism of food, religious taboos of food), and leisure activities (Bhugra and Becker 2005).

Models of Racial Identity

Models of racial identity, often structured in stages, highlight the process that individuals undertake in becoming aware of their sense of self in relation to race and ethnicity within the context of their families, communities, societies, and cultural histories. Influenced by the Civil Rights Movement, earlier racial identity models in the United States focused on White and Black racial identity development (Cross 1995; Helms 1990; Helms and Carter 1991). Since then, models have been created to incorporate other races, ethnicities, and cultures.

Although this chapter highlights two formative racial identity models (see next page), additional resources highlight racial identity models that incorporate other diverse groups, including those individuals who identify as multiracial (e.g., see Wijeyesinghe and Jackson 2012).

Aspects of racial, ethnic, and cultural identities are not always apparent and do not always factor into conscious processes for the counselor or client, but these factors still play a role in the therapeutic relationship. Identity development and formation help people make sense of themselves and the world around them. If positive racial, ethnic, and cultural messages are not available or supported in behavioral health services, counselors and clients can lack affirmative views of their own identities and may internalize negative messages or feel disconnected from their racial and cultural heritages. Counselors from mainstream society are less likely to be actively aware of their own ethnic and cultural identities; in particular, White Americans are not naturally drawn into examining their cultural identities, as they typically experience no dissonance when engaging in cultural activities.

In working to attain cultural competence, counselors must explore their own racial and cultural heritages and identities to gain a deeper understanding of personal development. Many models and theories of racial, ethnic, and cultural development are available; two common processes are presented below. Exhibit 2-1 highlights the racial/cultural identity development (R/CID) model (Sue and Sue 1999b) and the White racial identity development (WRID) model (Sue 2001). Although earlier work focused on a linear developmental process using stages, current thought centers on a more flexible process whereby identification status can loop back to an earlier process or move to a later phase.

Exhibit 2-1

Stages of Racial and Cultural Identity Development.

Using either model, counselors can explore relational and clinical challenges associated with a given phase. Without an understanding of the cultural identity development process, counselors—regardless of race or ethnicity—can unwittingly minimize the importance of racial and ethnic experiences. They may fail to identify cultural needs and secure appropriate treatment services, unconsciously operate from a superior perspective (e.g., judging a specific behavior as ineffectual, a sign of resistance, or a symptom of pathology), internalize a client's reaction (e.g., an African American counselor feeling betrayed or inadequate when a client of the same race requests a White American counselor for therapy during an initial interview), or view a client's behavior through a veil of societal biases or stereotypes. By acknowledging and endorsing the active process of racial and cultural identity development, counselors from diverse groups can normalize their own development processes and increase their awareness of clients' parallel processes of identity development. In counseling, racial, ethnic, and cultural identities can be pivotal to the treatment process in the relationships not only between the counselor and client, but among everyone involved in the delivery of the client's behavioral health and primary care services (e.g., referral sources, family members, medical personnel, administrators). The case study on page 41 uses stages from the two models in Exhibit 2-1 to show the interactive process of racial and cultural identity development in the treatment context.

Cultural and racial identities are not static factors that simply mediate individual identity; they are dynamic, interactive developmental processes that influence one's willingness to acknowledge the effects of race, ethnicity, and culture and to act against racism and disparity across relationships, situations, and environments (for a review of racial and cultural identity development, see Sue and Sue 2013c). For counselors and clinical supervisors, it is essential to understand the dynamic nature of cultural identity in all exchanges. Starting with a personal appraisal, clinical staff members can begin to reflect—without judgment—on how their own racial and cultural identities influence their decisions, treatment planning, case presentation, supervision, and interactions with other staff members. Clinicians can map the interactive influences of cultural identity development among clients, the clients' families, staff members, the organization, other agencies, and any other entities involved in the client's treatment. Using mapping (see the “How To Map Racial and Cultural Identity Development” box on the next page) as preparation for counseling, treatment planning, or clinical supervision, clinicians can gain awareness of the many forces that influence culturally responsive treatment.

Case Study for Counselors: Racial and Cultural Identity

The client is a 20-year-old Latino man. His father immigrated to the United States from Mexico as a child, and his mother (of Latino/Middle Eastern descent) grew up near Albuquerque, New Mexico. Throughout the initial phase of mental health treatment, the client presented feelings, attitudes, and behavior consistent with the resistance and immersion stage of the R/CID model. During group counseling in a partial hospitalization program, the client said that he did not think treatment was going to work. He believed that no one in treatment, except other Latino men, really understood him or his life experiences. He thought that his low mood was due, in part, to his recent job loss.

The client's current concerns, symptoms, and diagnosis (bipolar I) were presented and discussed during the treatment team meeting. The client's counselor (a White American man in the dissonance stage of the WRID model) was concerned that the client might leave treatment against medical advice and also stated that this would not be the first time a Latino client had done so. The team recognized that a Latino counselor would likely be useful in this situation (depending on the counselor's cultural competence). However, no Latino counselor was available, so the team decided that the client's current counselor should try to gain support from the client's parents to encourage the client to stay in treatment.

Because the client had signed an appropriate release of information, his counselor was able to contact the parents and arrange a family session. During the family session, the counselor brought up the client's need for a Latino counselor. His parents disagreed, expressing their belief that it was important for their son to learn to relate to the counselor. They said that this was just an excuse their son was using to leave treatment, which had happened before. The parents' reaction exemplified a conformity response, although other information would need to have been gathered to determine their current stage more accurately.

The counselor, client, parents, and organization were operating from different stages of racial and cultural identity development. Considering the lack of a proactive plan to provide appropriate resources—including the hiring of Latino staff or the development of other culturally appropriate resources (e.g., a peer counselor program)—the organization was most likely in the conformity phase of the WRID model. The counselor had some awareness of the client's racial and cultural needs and of the organization's failure to meet them, but he alienated the client despite his good intentions and reinforced mistrust by engaging the client's parents before working directly with the client. Had the counselor taken the time to understand the client's concerns and needs, he would likely have created an opportunity to challenge his own beliefs, learn more about the client's racial and cultural experiences and values, advocate for more appropriate resources for the client within the organization, be more flexible with treatment solutions, and enable the client to have an experience that exceeded his expectations of the treatment provider.

Worldview: The cultural lens of counseling

The term “worldview” refers to a set of assumptions that guide how one sees, thinks about, experiences, and interprets the world (Koltko-Rivera 2004). Starting in early childhood, worldview development is facilitated by significant relationships (particularly with parents and family members) and is shaped by the individual's environment and life experiences, influencing values, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. In more simplistic terms, each person's worldview is like a pair of glasses with colored lenses—the person takes in all of life's experiences through his or her own uniquely tinted view. Not unlike clients, counselors enter the treatment process with their own cultural worldviews that shape their concept of time; definition of family; organization of priorities and responsibilities; orientation to self, family, and/or community; religious or spiritual beliefs; ideas about success; and so on (Exhibit 2-2).

Exhibit 2-2

Counselor Worldview.

How To Map Racial and Cultural Identity Development

Completing this diagram can give a clearer perspective on past and anticipated dialog among key stakeholders. The diagram can be used as a training tool to teach racial and cultural identity development, to help clinicians and organizations recognize their own development, to explore clinical issues and dialogs that occur when diverse parties are at similar or different developmental stages, and to develop tools and resources to address issues that arise from this developmental process. Using case studies, this diagram can serve as an interactive educational exercise to help counselors, clinical supervisors, and agencies gain awareness of the effects of race, ethnicity, and cultural groups.

Materials needed: Paper and pencils; handouts on the R/CID and WRID models.

Instructions

- Identify all relevant parties, including client, counselor, family, supervisor, referral source, other staff members, and staff from other agencies (e.g., probation/parole, medical center/office, child and youth services). Include yourself. Place the names at each intersection of the hexagon.

- List the common statements and behaviors (including lack of verbal responses) that you witness regarding the cultural needs of the client and/or the general statements made by each party regarding race, ethnicity, and culture. Write these as one-line abbreviated phrases that represent each person/agency's stance under the appropriate entry on the diagram.

- Using current information, choose the cultural identity development stage that best fits the statements or behaviors (knowing that you may be inaccurate); write it under each name.

However, counselors also contend with another worldview that is often invisible but still powerful—the clinical worldview (Bhugra and Gupta 2010; Tilburt and Geller 2007; Tseng and Streltzer 2004). Influenced by education, clinical training, and work experiences, counselors are introduced into a culture that reflects specific counseling theories, techniques, treatment modalities, and general office practices. This worldview, coupled with their personal cultural worldview, significantly shapes the counselor's beliefs pertaining to the nature of wellness, illness, and healing; interviewing skills and behavior; diagnostic impressions; and prognosis. Moreover, it influences the definition of normal versus abnormal or disordered behavior, the determination of treatment priorities, the means of intervention, and the definitions of successful outcomes and treatment failures.

Foremost, counselors need to remember that worldviews are often unspoken and inconspicuous; therefore, considerable reflection and self-exploration are needed to identify how their own cultural worldviews influence their interactions both inside and outside of counseling. Clinical staff members need to question how their perspectives are perpetuated in and shape client–counselor interactions, treatment decisions, planning, and selected counseling approaches. In sum, culturally responsive practice involves an understanding of multiple perspectives and how these worldviews interact throughout the treatment process—including the views of the counselor, client, family, other clients and staff members, treatment program, organization, and other agencies, as well as the community.

Stereotypes, prejudices, and history

Cultural competence involves counselors' willingness to explore their own histories of prejudice, cultural stereotyping, and discrimination. Counselors need to be aware of how their own perceptions of self and others have evolved through early childhood influences and other life experiences. For example, how were stereotypes of their own races and ethnic heritages perpetuated in their upbringing? What myths and stereotypes were projected onto other groups? What historical events shaped experiences, opportunities, and perceptions of self and others?

Regardless of their race, cultural group, or ethnic heritage, counselors need to examine how they have directly or indirectly been affected by individual, organizational, and societal stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. How have certain attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors functioned as deterrents to obtaining equitable opportunities? In what ways have discrimination and societal biases provided benefits to them as individuals and as counselors? Even though these questions can be uncomfortable, difficult, or painful to explore, awareness is essential regarding how these issues affect one's role as a counselor, status in the organization, and comfort level in exploring clients' life experiences and perceptions during the treatment process. If counselors avoid or minimize the relevance of bias and discrimination in self-exploration, they will likely do the same in the assessment and counseling process.

All counselors should examine their stereotypes, prejudices, and emotional reactions toward others, including individuals from their own races or cultural backgrounds and individuals from other groups. They should examine how these attitudes and biases may be detrimental to clients in treatment for substance-related and mental disorders.

Clients can have behavioral health issues and healthcare concerns associated with discrimination. If counselors are blind to these issues, they can miss vital information that influences client responses to treatment and willingness to follow through with continuing care and ancillary services. For example, a counselor may refer a client to a treatment program without noting the client's history or perceptions of the recommended program or type of program. The client may initially agree to attend the program but not follow through because of past negative experiences and/or the perception within his or her racial/ethnic community that the service does not provide adequate treatment for clients of color.

Trust and power

Counselors need to understand the impact of their role and status within the client–counselor relationship. Client perceptions of counselors' influence, power, and control vary in diverse cultural contexts. In some contexts, counselors can be seen as all-knowing professionals, but in others, they can be viewed as representatives of an unjust system. Counselors need to explore how these dynamics affect the counseling process with clients from diverse backgrounds. Do client perceptions inhibit or facilitate the process? How do they affect the level of trust in the client–counselor relationship? These issues should be identified and addressed early in the counseling process. Clients should have opportunities to talk about and process their perceptions, past experiences, and current needs.

Practicing within limits

A key element of ethical care is practicing within the limits of one's competence. Counselors must engage in self-exploration, critical thinking, and clinical supervision to understand their clinical abilities and limitations regarding the services that they are able to provide, the populations that they can serve, and the treatment issues that they have sufficient training to address. Cultural competence requires an ability to assess accurately one's clinical and cultural limitations, skills, and expertise. Counselors risk providing services beyond their expertise if they lack awareness and knowledge of the influence of cultural groups on client–counselor relationships, clinical presentation, and the treatment process or if they minimize, ignore, or avoid viewing treatment in a cultural context.

Advice to Counselors and Clinical Supervisors: Using the RESPECT Mnemonic To Reinforce Culturally Responsive Attitudes and Behaviors

- Respect—Understand how respect is shown within given cultural groups. Counselors demonstrate this attitude through verbal and nonverbal communications.

- Explanatory model—Devote time in treatment to understanding how clients perceive their presenting problems. What are their views about their own substance abuse or mental symptoms? How do they explain the origin of current problems? How similar or different is the counselor's perspective?

- Sociocultural context—Recognize how class, race, ethnicity, gender, education, socioeconomic status, sexual and gender orientation, immigrant status, community, family, gender roles, and so forth affect care.

- Power—Acknowledge the power differential between clients and counselors.

- Empathy—Express, verbally and nonverbally, the significance of each client's concerns so that he or she feels understood by the counselor.

- Concerns and fears—Elicit clients' concerns and apprehensions regarding help-seeking behavior and initiation of treatment.

- Therapeutic alliance/Trust—Commit to behaviors that enhance the therapeutic relationship; recognize that trust is not inherent but must be earned by counselors.

Sources: Bigby and American College of Physicians 2003; Campinha-Bacote et al. 2005.

Some counselors may assume that they have cultural competence based on having similar experiences as clients, being from the same race as clients, identifying as a member of the same ethnic heritage or cultural group as clients, or attending training on cultural competence. Other counselors may assume competence based on their current or prior relationships with others from the same race or cultural background as their clients. These experiences can be helpful and filled with many potential learning opportunities, but they do not make an individual eligible or competent to provide multicultural counseling. Likewise, the assumption that a person from the same cultural group, race, or ethnic heritage will intrinsically understand a client from a similar background is operating out of two common myths: the “myth of sameness” (i.e., that people from the same cultural group, race, or ethnicity are alike) and the myth that “familiarity equals competence” (Srivastava 2007). The Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development adopted a set of counselor competencies that was endorsed by the American Counseling Association (ACA) for counselors who work with a multicultural clientele (Exhibit 2-3). Competencies address the attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and skills associated with the counselor's need for self-knowledge.

Exhibit 2-3

ACA Counselor Competencies: Counselors' Awareness of Their Own Cultural Values and Biases.

Knowledge of Other Cultural Groups

In addition to an understanding of themselves and how their cultural groups and values can affect the therapeutic process, culturally competent counselors work to acquire cultural knowledge and understanding of clients and staff with whom they work. From the outset, counselors need general knowledge and awareness when working with other cultural groups in counseling. For example, they should acknowledge that culture influences communication patterns, values, gender roles and socialization, clinical presentations of distress, counseling expectations, and behavioral norms and expectations in and outside the counseling session (e.g. , touching, greetings, gift-giving, accompaniment in sessions, level of formality between counselor and client). Counselors should filter and interpret client presentation from a broad cultural perspective instead of using only their own cultural groups or previous client experiences as reference points.

Counselors also need to invest the time to know clients and their cultures. Culturally responsive practice involves a commitment to obtaining specific cultural knowledge, not only through ongoing client interactions, but also through the use of outside resources, cultural training seminars and programs, cultural events, professional consultations, cultural guides, and clinical supervision. Counselors need to be mindful that they will not know everything about a specific population or initially comprehend how an individual client endorses or engages in specific cultural practices, beliefs, and values. For instance, some clients may not identify with the same cultural beliefs, practices, or experiences as other clients from the same cultural groups. Nevertheless, counselors need to be as knowledgeable as possible and attend to these cultural attributes—beginning with the intake and assessment process and continuing throughout the counseling and treatment relationship. For a review of content areas essential in knowing other cultural groups, refer to the “What Are the Cross-Cutting Factors in Race, Ethnicity, and Culture” section in Chapter 1. These cultural knowledge content areas include:

- Language and communication.

- Geographic location.

- Worldview, values, and traditions.

- Family and kinship.

- Gender roles.

- Socioeconomic status and education.

- Immigration, migration, and acculturation stress.

- Acculturation and cultural identification.

- Heritage and history.

- Sexuality.

- Religion and spirituality.

- Health, illness, and healing.

“Become familiar with the community in which the client lives and the general cultural norms of the individual client. This can be accomplished by visiting with people who know the community well, attending important community celebrations and other events, asking open-ended questions about community concerns and quality of life, and identifying community capacities that affect wellness in the community.”

(Perez and Luquis 2008, p. 177)

Counselors should not make assumptions about clients' race, ethnic heritage, or culture based on appearance, accents, behavior, or language. Instead, counselors need to explore with clients their cultural identity, which can involve multiple identities (Lynch and Hanson 2011). Counselors should discuss what cultural identity means to clients and how it influences treatment. For example, a young adult two-spirited (gay) American Indian man may be more concerned with having access to traditional healing practices than to specialized services for gay men. Counselors and clients should collaboratively examine presenting treatment issues and obstacles to engaging in behavioral health treatment and maintaining recovery, and they should discuss how cultural groups and cultural identities can serve as guideposts in treatment planning.

Exhibit 2-4 lists ACA-endorsed counselor competencies for knowledge of the worldviews of clients from diverse cultural groups.

Exhibit 2-4

ACA Counselor Competencies: Awareness of Clients' Worldviews.

Cultural Knowledge of Behavioral Health

Counselors should learn how culture interacts with health beliefs, substance use, and other behavioral health issues. They can access literature and training that address cultural contexts and meanings of substance use, behavioral and emotional reactions, help-seeking behavior, and treatment. Chapter 5 gives information on culturally responsive behavioral health services for major ethnic and racial groups. The how-to box below lists ways to improve one's cultural knowledge of health issues by acquiring knowledge in key areas to work successfully with diverse clients:

- Patterns of substance use and treatment-seeking behavior specific to people of diverse racial and cultural backgrounds.

- Beliefs and traditions surrounding substance use, including cultural norms concerning the use of alcohol and drugs.

- Beliefs about treatment, including expectations and attitudes toward health care and counseling.

- Community perceptions of behavioral health treatment.

- Obstacles encountered by specific populations that make it difficult to access treatment, such as geographic distance from treatment services.

- Patterns of co-occurring disorders and conditions specific to people from diverse racial and cultural backgrounds (e.g., culturally specific syndromes, earlier onset of diabetes, higher prevalence of depression and substance dependence).

- Assessment and diagnosis, including culturally appropriate screening and assessment and awareness of common diagnostic biases associated with symptom presentation.

- Individual, family, and group therapy approaches that hold promise in addressing mental and substance-related disorders specific to the racial and cultural backgrounds of diverse clients.

- Culturally appropriate peer support, mutual-help, and other support groups (e.g., the Wellbriety movement, a culturally appropriate 12-Step program for Native American people).

- Traditional healing and complementary methods (e.g., use of spiritual leaders, herbs, and rituals).

- Continuing care and relapse prevention, including attention to clients' cultural environments, treatment needs, and accessibility of care within their communities.

- Treatment engagement/retention patterns.

How To Improve Cultural Knowledge of Health, Illness, and Healing

To promote culturally responsive services, counselors need to acquire cultural knowledge regarding concepts of health, illness, and healing. The following questions highlight many of the culturally related issues that are prevalent in and pertinent to assessment, treatment planning, and case management. This list of considerations can help facilitate discussions in counseling and clinical supervision contexts:

- Does the cultural group in question consider psychological, physical, and spiritual health or well-being as separate entities or as unified aspects of the whole person?

- How are illnesses and healing practices defined and conceptualized?

- What are acceptable behaviors for managing stress?

- How do people who belong to the culture in question typically express emotions and emotional distress?

- What behaviors, practices, or customs do members of this culture consider to be preventive?

- What words do people from this cultural group use to describe a particular problem?

- How do members of the group explain the origins or causes of a particular condition?

- Are there culturally specific conditions or cultural concepts of distress?

- Are there specific biological and physiological variations among members of this population?

- What are the common symptoms that lead to misdiagnosis within this population?

- Where do people from this cultural group typically seek help?

- What traditional healing practices and treatments are endorsed by members of this group?

- Are there biomedical treatments or procedures that would typically be unacceptable?

- Are there specific counseling approaches more congruent with the beliefs of most members?

- What are common health inequities, including social determinants of health, for this population?

- What are acceptable caregiving practices?

- Do members of this group attach honor to caring for family members with specific diseases?

- Are individuals with specific conditions shunned from the community?

- What are the roles of family members in providing health care and in making decisions?

- Is discussing consequences of and prognosis for behaviors, conditions, or diseases acceptable?

- Is it customary for family members to withhold prognosis from the client?

Skill Development

Becoming culturally competent is an ongoing process—one that requires introspection, awareness, knowledge, and skill development. Counselors need to develop a positive attitude toward learning about multiple cultural groups; in essence, counselors should commit to cultural competence and the process of growth. This commitment is evidenced via investment in ongoing learning and the pursuit of culturally congruent skills. Counselors can demonstrate commitment to cultural competence through the attitudes and corresponding behaviors indicated in Exhibit 2-5.

Exhibit 2-5

Attitudes and Behaviors of Culturally Competent Counselors.

Beyond the commitment to and development of these fundamental attitudes and behaviors, counselors need to work toward intervention strategies that integrate the skills discussed in the following sections.

Frame issues in culturally relevant ways

Counselors should frame clinical issues with culturally appropriate references. For example, in cultural groups that value the community or family as much as the individual, it is helpful to address substance abuse in light of its consequences to family or the community. The counselor might ask, “How are your family and community affected by your use? How do family and community members feel when they see you high?” For clients who place more value on their independence, it can be more effective to point out how substance dependence undermines their ability to manage their own lives through questions like “How might your use affect your ability to reach your goals?”

Allow for complexity of issues based on cultural context

Counselors must take care with suggesting simple solutions to complex problems. It is often better to acknowledge the intricacies of the client's cultural context and circumstances. For instance, a Native American single mother who upholds traditional values could balk at a suggestion to stop spending time with family members who drink heavily. Here, the counselor might encourage the woman to broaden support within her community by connecting with an elder who supports recovery or by engaging in a women's talking circle. Likewise, a referral for a psychiatric evaluation for major depression may not be an appropriate initial recommendation for a Chinese client who relies on cultural remedies and healing traditions. An alternative approach would be to explore the client's beliefs in healing, develop steps that respect and incorporate the client's help-seeking practices, and coordinate services to secure a culturally responsive intervention (Cardemil et al. 2011; Gallardo et al. 2012; Lynch and Hanson 2011).

Make allowances for variations in the use of personal space

Cultural groups have different expectations and norms of propriety concerning how close people can be while they communicate and how personal communications can be depending on the type of relationship (e.g., peers versus elders). The concept of personal space involves more than the physical distance between people. It also involves cultural expectations regarding posture or stance and the use of space within a given environment. These cultural expectations, although they are subtle, can have an impact on treatment. For example, an Alaska Native may feel more comfortable sitting beside a counselor, whereas a European may prefer to be separated from a counselor by a desk (Sue and Sue 2013a). The use of space can also be a nonverbal expression of power. Standing too close to someone can, for example, suggest power over them. Standing too far away or sitting behind a desk can indicate aloofness. Acceptable or expected degrees of closeness between people are culturally specific; counselors should be educated on the general parameters and expectations of the given population. However, counselors should not predetermine the clients' expectations; instead, they should follow the clients' lead and inquire about their preferences.

Advice to Counselors and Clinical Supervisors: Behaviors for Counselors To Avoid

- Addressing clients informally; counselors should not assume familiarity until they grasp cultural expectations and client preferences.

- Failing to monitor and adjust to the client's verbal pacing (e.g., not allowing time for clients to respond to questions).

- Using counseling jargon and treatment language (e.g., “I am going to send you to our primary stabilization program to obtain a biopsychosocial and then, afterwards, to partial”).

- Using statements based on stereotypes or other preconceived ideas generated from experiences with other clients from the same culture.

- Using gestures without understanding their meaning and appropriate context within the given culture.

- Ignoring the relevance of cultural identity in the client-counselor relationship.

- Neglecting the client's history (i.e., not understanding the client's individual and cultural background).

- Providing an explanation of how current difficulties can be resolved without including the client in the process to obtain his or her own explanations of the problems and how he or she thinks these problems should be addressed.

- Downplaying the importance of traditional practices and failing to coordinate these services as needed.

Sources: Fontes 2008; Lynch and Hanson 2011; Pack-Brown and Williams 2003; Srivastava 2007.

Display sensitivity to culturally specific meanings of touch

Some treatment and many support groups have opening or closing traditions that include holding hands or giving hugs. This form of touching can be very uncomfortable to new clients regardless of cultural groups; cultural prescriptions, including religious beliefs, concerning appropriate touching can compound this effect (Comas-Diaz 2012). Many cultural groups use touch to acknowledge or greet someone, to show respect or convey status or power, or to display comfort. As counselors, it is essential to understand cultural norms about touch, which often are guided by gender and age, and the contexts surrounding “appropriate” touch for specific cultural groups (Srivastava 2007). Counselors need to devote time to understanding their clients' norms for and interpretations of touch, to assisting clients in negotiating and upholding their cultural norms, and to helping clients understand the context and cultural norms that are likely to prevail in support and treatment groups.

Explore culturally based experiences of power and powerlessness

Ideas about power and powerlessness are influenced by the client's culture and social class. What constitutes power and powerlessness varies from culture to culture according to the individual's gender, age, occupation, ancestry, religious affiliation, and a host of other factors. For example, power can be defined in terms of one's place within the family, with the oldest member being the most powerful and the youngest being the least powerful. Even the words “power” and “powerlessness” carry cultural meaning. These words can carry negative connotations for clients with histories of discrimination and multiple experiences with racism, for some women, for indigenous peoples with histories of colonization, and for refugees or immigrants who have left oppressive regimes. In this regard, counselors should use these words carefully. For example, a Hmong refugee who experienced trauma in her country of origin could already feel helpless and powerless over the events that occurred; thus, the concept of powerlessness, often used in drug and alcohol treatment programs, can be contraindicated in addressing her substance-related disorder. However, a White American business executive who has authority over others and a history of financial influence may need help acknowledging that he cannot control his substance abuse.

Adjust communication styles to the client's culture

Cultural groups all have different communication styles. Norms for communicating vary in and between cultural groups based on class, gender, geographic origins, religion, subcultures, and other individual variations. Counselors should educate themselves as much as possible regarding the patterns of communicating in the client's cultural, racial, or ethnic population while also being aware of his/her own communication style. For a comprehensive guide in self-assessment and understanding of communication styles, refer to Culture Matters: The Peace Corps Cross-Cultural Workbook (Peace Corps Information Collection and Exchange 2012).

The following are general guidelines for ascertaining the client's communication style:

- Understand the client's verbal and nonverbal ways of communicating. Be aware of the possible need to move away from comprehending and interpreting client responses in conventional professional ways (Bland and Kraft 1998). Always be curious about the client's cultural context and be willing to seek clarification and better understanding from the client. It is as important for counselors to access and engage in cultural consultation to acquire more specific knowledge and experience.

- Styles of communication and nonverbal methods of communication are important aspects of cultural groups. Issues such as the appropriate space to have between people; preferred ways of moving, sitting, and standing; the meaning of gestures; and the degree of eye contact expected are all culturally defined and situation specific (Hall 1976). As an example, high-context cultural groups place greater importance on nonverbal cues and message context, whereas low-context cultural groups rely largely on verbal message content. Most Asian Americans come from high-context cultural groups in which sensitive messages are encoded carefully to avoid offending others. A provider who listens only to the content could miss the message. What is not said can possibly be more important than what is said.

- Listen to storytelling carefully, as it can be a way of communicating with the therapist. As in any good therapy, follow the associations and listen for possible metaphors to better understand relational meaning, cognition, and emotion within the context of the conversation.

How To Assess Differences in Communication Styles

This exercise can be used by counselors and clinical supervisors as a self-assessment tool and a means of exploring differences in communication styles among counselors, clients, and supervisors. It can also serve as a group exercise to help clients discuss and understand cultural differences in communicating with others. This self-administered tool promotes self-understanding and cultural knowledge. It is not an empirically based instrument, nor is it meant to assess client communication styles or skills formally.

Materials needed: Colored pencils/pens and copies of the exercise.

Instructions

- First, place an X along the line for each item that best matches your style or pattern of communication overall. Communication patterns can change across situations and environments depending on expectations, stress level, and familiarity, (e.g., attending a staff meeting versus spending time with friends); try to assign the style that best reflects your patterns across situations.

- After reviewing your own patterns, compare differences between you and your client, clinical supervisor, or fellow staff member. For example, select a recent client you treated and place a second X (using a different color pen) on each line to mark your perceived view of this client's communication style. Then examine the differences between you and your client and generate a list of potential misunderstandings that could occur due to these differences. Use clinical supervision to discuss how your own patterns can hinder and/or promote the counseling process.

| NONVERBAL PATTERNS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Eye Contact | ||

| When talking: Direct, sustained |

| Indirect or not sustained |

| When listening: Direct, sustained |

| Indirect or not sustained |

| Vocal Pitch/Tone | ||

| High/loud |

| Low/soft |

| More expressive |

| Less expressive |

| Speech Rate | ||

| Fast |

| Slow |

| Pauses or Silence | ||

| Little use of silence in dialog |

| Pauses; uses silence in dialog |

| Facial Expressions | ||

| Frequent expression |

| Little expression |

| Use of Other Gestures | ||

| Frequent expression |

| Little expression |

| VERBAL PATTERNS | ||

| Emotional Expression | ||

| Does express and identify feelings in speech |

| Does not express or identify feelings in speech |

| Self-Disclosure | ||

| Frequently |

| Rarely or little |

| Formality | ||

| Informal |

| Formal in addressing others and showing respect |

| Directness | ||

| Verbally explicit |

| Indirect; subtle; doesn't believe in saying everything |

| Context | ||

| Low context; relies more on words to convey meaning |

| High context: verbal and nonverbal cues convey much of the meaning |

| Orientation | ||

| Orientation to self; use of “I” statements |

| Orientation to others, use of plural and third-person pronouns (e.g., we, he) |

Other Things To Consider in Exploring Communication Styles

- Are there known differences in body language and expression within the given cultural group?

- What are the common, culturally appropriate parameters of touch across situations? For example, a handshake could be appropriate as a means of introduction for one cultural group but not for another.

- How is personal space used in and outside of the office? Are there known cultural patterns in the use of space and proximity of communication?

- What verbal and nonverbal counselor behaviors may affect trust in the counseling process?

Sources: Cormier et al. 2009; Fontes 2008; Srivastava 2007; Sue and Sue 2013a.

Interpret emotional expressions in light of the client's culture

Feelings are expressed differently across and within cultural groups and are influenced by the nature of a given event and the individuals involved in the situation. A certain level of emotional expression can be socially appropriate within one culture yet inappropriate in another. In some cultural groups, feelings may not be expressed directly, whereas in other cultural groups, some emotions are readily expressed and others suppressed. For example, expressions of sadness may at first be more readily shared by some clients in counseling settings, whereas others may find it more comfortable to express anger as their initial response. Counselors must recognize that not all cultures place the same value on verbalizing feelings. In fact, clients from some cultures may not perceive that emotional expression is a worthy course of treatment and healing at all. Thus, counselors should not impose a prescribed approach that measures progress and equates healing with the ability to display emotions. Likewise, counselors should be careful not to attribute meaning based on their own cultural backgrounds or to project their own feelings onto clients' experiences. Instead, counselors need to assist their clients in identifying and labeling feelings within their own cultural contexts.

Expand roles and practices

Counselors need to acquire a mindset that allows for more flexible roles and practices—while still maintaining appropriate professional boundaries—when working with clients. Some clients whose culture places considerable emphasis upon and orientation toward family could look to counselors for advice with unrelated issues pertaining to other family members. Other clients may expect a more prescribed and structured approach in which counselors give specific recommendations and advice in the session. For example, Asian American clients appear to expect and benefit from a more directive and highly structured approach (Fowler et al. 2011; Lee and Mock 2005a; Sue 2001; Uba 1994). Still others could expect that counselors be connected to their communities through participation in community events, in working with traditional healers, or in building collaborative relationships with other community agencies. As counselors, it is important to understand the cultural contexts of clients and how this translates to expectations in the client–counselor relationship. The appropriate role usually Results from the counselor's understanding of and sensitivity to the values, cultures, and special needs of the individuals and groups being served (Sue and Sue 2013d). Counselors need to adopt an ongoing commitment to developing skills and endorsing practices that assist clients in receiving and experiencing the best possible care. Exhibit 2-6 lists counselor competencies endorsed by ACA for culturally appropriate intervention strategies.

Exhibit 2-6

ACA Counselor Competencies: Culturally Appropriate Intervention Strategies.

Providing good care goes beyond counselors' general knowledge, clinical skills, and approaches; it involves understanding the multicultural context of clients and of themselves as counselors. Cultural competence is an ethical issue requiring counselors to be invested in developing the tools to provide culturally congruent care—care that matches the needs and context of the client. For a review of ethics and ethical dilemmas in a multicultural context, refer to Pack-Brown and Williams (2003).

Self-Assessment for Individual Cultural Competence

Several instruments for evaluating an individual's cultural competence have been developed and are available online. One assessment tool that has been widely circulated is Goode's Self-Assessment Checklist for Personnel Providing Services and Supports to Children and Youth With Special Health Needs and Their Families. It can be adapted for counselors treating adult clients with behavioral health concerns. This tool and other additional resources are provided in Appendix C. For an interactive Web-based tool on cultural competence awareness, visit the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Web site (http://www.asha.org).

- Core Competencies for Counselors and Other Clinical Staff - Improving Cultural C...Core Competencies for Counselors and Other Clinical Staff - Improving Cultural Competence

- cytochrome oxidase subunit 1, partial (mitochondrion) [Rhabdosargus holubi]cytochrome oxidase subunit 1, partial (mitochondrion) [Rhabdosargus holubi]gi|328487181|gb|AEB17884.1|Protein

- Chain C, Hemoglobin subunit alphaChain C, Hemoglobin subunit alphagi|2214226696|pdb|7UD7|CProtein

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...

![Click on image to zoom Graphic: Hexagon, segmented into six parts. Clockwise from the top, the segments are labeled: “Probation/Parole,” “Organization (e.g., ‘We just can't change our policies and procedures to match every circumstance that a client presents.’ [Conformity phase]),” Client (‘I would benefit more from a White counselor’ [Conformity phase]),” “Counselor (e.g., ‘I consider my approach eclectic. It is focused on the individual needs of clients.’ [Conformity phase]),” “Family,” and “Clinical Supervisor (e.g., ‘We need to begin developing guidelines and strategies to meet client needs. I have become concerned that clients are leaving prematurely.’ [Introspective phase].”](/books/NBK248422/bin/ch2f3.jpg)