NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). Improving Cultural Competence. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 59.)

Zhang Min, a 25-year-old first-generation Chinese woman, was referred to a counselor by her primary care physician because she reported having episodes of depression. The counselor who conducted the intake interview had received training in cultural competence and was mindful of cultural factors in evaluating Zhang Min. The referral noted that Zhang Min was born in Hong Kong, so the therapist expected her to be hesitant to discuss her problems, given the prejudices attached to mental illness and substance abuse in Chinese culture. During the evaluation, however, the therapist was surprised to find that Zhang Min was quite forthcoming. She mentioned missing important deadlines at work and calling in sick at least once a week, and she noted that her coworkers had expressed concern after finding a bottle of wine in her desk. She admitted that she had been drinking heavily, which she linked to work stress and recent discord with her Irish American spouse.

Further inquiry revealed that Zhang Min's parents, both Chinese, went to school in England and sent her to a British school in Hong Kong. She grew up close to the British expatriate community, and her mother was a nurse with the British Army. Zhang Min came to the United States at the age of 8 and grew up in an Irish American neighborhood. She stated that she knew more about Irish culture than about Chinese culture. She felt, with the exception of her physical features, that she was more Irish than Chinese—a view accepted by many of her Irish American friends. Most men she had dated were Irish Americans, and she socialized in groups in which alcohol consumption was not only accepted but expected.

Zhang Min first started to drink in high school with her friends. The counselor realized that what she had learned about Asian Americans was not necessarily applicable to Zhang Min and that knowledge of Zhang Min's entire history was necessary to appreciate the influence of culture in her life. The counselor thus developed treatment strategies more suitable to Zhang Min's background.

Zhang Min's case demonstrates why thorough evaluation, including assessment of the client's sociocultural background, is essential for treatment planning. To provide culturally responsive evaluation and treatment planning, counselors and programs must understand and incorporate relevant cultural factors into the process while avoiding a stereotypical or “one-size-fits-all” approach to treatment. Cultural responsiveness in planning and evaluation entails being open minded, asking the right questions, selecting appropriate screening and assessment instruments, and choosing effective treatment providers and modalities for each client. Moreover, it involves identifying culturally relevant concerns and issues that should be addressed to improve the client's recovery process.

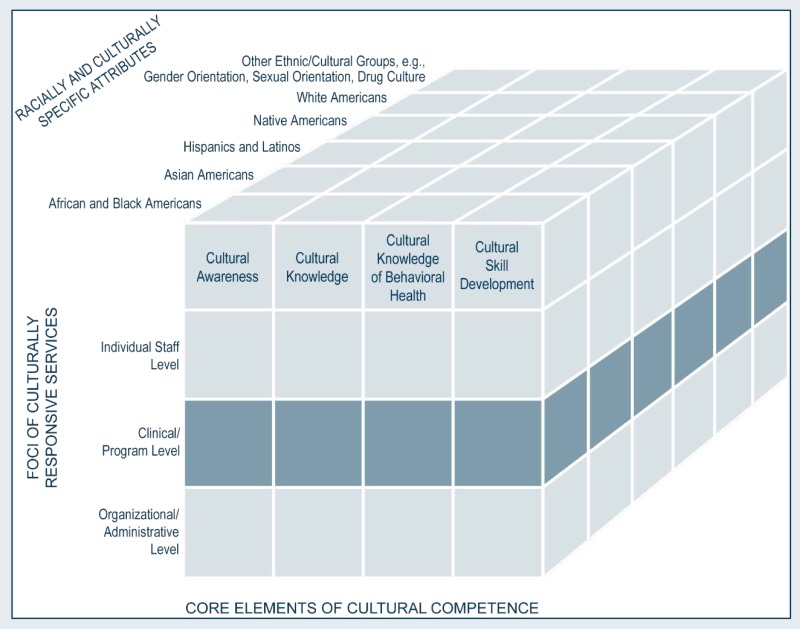

This chapter offers clinical staff guidance in providing and facilitating culturally responsive interviews, assessments, evaluations, and treatment planning. Using Sue's (2001) multidimensional model for developing cultural competence, this chapter focuses on clinical and programmatic decisions and skills that are important in evaluation and treatment planning processes. The chapter is organized around nine steps to be incorporated by clinicians, supported in clinical supervision, and endorsed by administrators.

Step 1. Engage Clients

Once clients are in contact with a treatment program, they stand on the far side of a yet-to-be-established therapeutic relationship. It is up to counselors and other staff members to bridge the gap. Handshakes, facial expressions, greetings, and small talk are simple gestures that establish a first impression and begin building the therapeutic relationship. Involving one's whole being in a greeting—thought, body, attitude, and spirit—is most engaging.

Fifty percent of racially and ethnically diverse clients end treatment or counseling after one visit with a mental health practitioner (Sue and Sue 2013e). At the outset of treatment, clients can feel scared, vulnerable, and uncertain about whether treatment will really help. The initial meeting is often the first encounter clients have with the treatment system, so it is vital that they leave feeling hopeful and understood. Paniagua (1998) describes how, if a counselor lacks sensitivity and jumps to premature conclusions, the first visit can become the last:

Pretend that you are a Puerto Rican taxi driver in New York City, and at 3:00 p.m. on a hot summer day you realize that you have your first appointment with the therapist…later, you learned that the therapist made a note that you were probably depressed or psychotic because you dressed carelessly and had dirty nails and hands…would you return for a second appointment? (p. 120)

To engage the client, the counselor should try to establish rapport before launching into a series of questions. Paniagua (1998) suggests that counselors should draw attention to the presenting problem “without giving the impression that too much information is needed to understand the problem” (p. 18). It is also important that the client feel engaged with any interpreter used in the intake process. A common framework used in many healthcare training programs to highlight culturally responsive interview behaviors is the LEARN model (Berlin and Fowkes 1983). The how-to box on the next page presents this model.

Improving Cross-Cultural Communication

Health disparities have multiple causes. One specific influence is cross-cultural communication between the counselor and the client. Weiss (2007) recommends these six steps to improve communication with clients:

- Slow down.

- Use plain, nonpsychiatric language.

- Show or draw pictures.

- Limit the amount of information provided at one time.

- Use the “teach-back” method. Ask the client, in a nonthreatening way, to explain or show what he or she has been told.

- Create a shame-free environment that encourages questions and participation.

Step 2. Familiarize Clients and Their Families With Treatment and Evaluation Processes

Behavioral health treatment facilities maintain their own culture (i.e., the treatment milieu). Counselors, clinical supervisors, and agency administrators can easily become accustomed to this culture and assume that clients are used to it as well. However, clients are typically new to treatment language or jargon, program expectations and schedules, and the intake and treatment process. Unfortunately, clients from diverse racial and ethnic groups can feel more estranged and disconnected from treatment services when staff members fail to educate them and their families about treatment expectations or when the clients are not walked through the treatment process, starting with the goals of the initial intake and interview. By taking the time to acclimate clients and their families to the treatment process, counselors and other behavioral health staff members tackle one obstacle that could further impede treatment engagement and retention among racially and ethnically diverse clients.

How To Use the LEARN Mnemonic for Intake Interviews

Listen to each client from his or her cultural perspective. Avoid interrupting or posing questions before the client finishes talking; instead, find creative ways to redirect dialog (or explain session limitations if time is short). Take time to learn the client's perception of his or her problems, concerns about presenting problems and treatment, and preferences for treatment and healing practices.

Explain the overall purpose of the interview and intake process. Walk through the general agenda for the initial session and discuss the reasons for asking about personal information. Remember that the client's needs come before the set agenda for the interview; don't cover every intake question at the expense of taking time (usually brief) to address questions and concerns expressed by the client.

Acknowledge client concerns and discuss the probable differences between you and your clients. Take time to understand each client's explanatory model of illness and health. Recognize, when appropriate, the client's healing beliefs and practices and explore ways to incorporate these into the treatment plan.

Recommend a course of action through collaboration with the client. The client must know the importance of his or her participation in the treatment planning process. With client assistance, client beliefs and traditions can serve as a framework for healing in treatment. However, not all clients have the same expectations of treatment involvement; some see the counselor as the expert, desire a directive approach, and have little desire to participate in developing the treatment plan themselves.

Negotiate a treatment plan that weaves the client's cultural norms and lifeways into treatment goals, objectives, and steps. Once the treatment plan and modality are established and implemented, encourage regular dialog to gain feedback and assess treatment satisfaction. Respecting the client's culture and encouraging communication throughout the process increases client willing to engage in treatment and to adhere to the treatment plan and continuing care recommendations.

Sources: Berlin and Fowkes 1983; Dreachslin et al. 2013; Ring 2008.

Step 3. Endorse Collaboration in Interviews, Assessments, and Treatment Planning

Most clients are unfamiliar with the evaluation and treatment planning process and how they can participate in it. Some clients may view the initial interview and evaluation as intrusive if too much information is requested or if the content is a source of family dishonor or shame. Other clients may resist or distrust the process based on a long history of racism and oppression. Still others feel inhibited from actively participating because they view the counselor as the authority or sole expert.

The counselor can help decrease the influence of these issues in the interview process through a collaborative approach that allows time to discuss the expectations of both counselor and client; to explain interview, intake, and treatment planning processes; and to establish ways for the client to seek clarification of his or her assessment results (Mohatt et al. 2008a). The counselor can encourage collaboration by emphasizing the importance of clients' input and interpretations. Client feedback is integral in interpreting results and can identify cultural issues that may affect intake and evaluation (Acevedo-Polakovich et al. 2007). Collaboration should extend to client preferences and desires regarding inclusion of family and community members in evaluation and treatment planning.

Step 4. Integrate Culturally Relevant Information and Themes

By exploring culturally relevant themes, counselors can more fully understand their clients and identify their cultural strengths and challenges. For example, a Korean woman's family may serve as a source of support and provide a sense of identity. At the same time, however, her family could be ashamed of her co-occurring generalized anxiety and substance use disorders and respond to her treatment as a source of further shame because it encourages her to disclose personal matters to people outside the family. The following section provides a brief overview of suggested strength-based topics to incorporate into the intake and evaluation process.

Advice to Counselors: Asking About Culture and Acculturation

A thoughtful exploration of cultural and ethnic identity issues will provide clues for determining cultural, racial, and ethnic identity. There are numerous clues that you may derive from your clients' answers, and they cannot all be covered in this TIP; this is only one set of sample questions (Fontes 2008). Ask these questions tactfully so they do not sound like an interrogation. Try to integrate them naturally into a conversation rather than asking one after another. Not all questions are relevant in all settings. Counselors can adapt wording to suit clients' cultural contexts and styles of communication, because the questions listed here and throughout this chapter are only examples:

- Where were you born?

- Whom do you consider family?

- What was the first language you learned?

- Which other language(s) do you speak?

- What language or languages are spoken in your home?

- What is your religion? How observant are you in practicing that religion?

- What activities do you enjoy when you are not working?

- How do you identify yourself culturally?

- What aspects of being ________ are most important to you? (Use the same term for the identified culture as the client.)

- How would you describe your home and neighborhood?

- Whom do you usually turn to for help when facing a problem?

- What are your goals for this interview?

Immigration History

Immigration history can shed light on client support systems and identify possible isolation or alienation. Some immigrants who live in ethnic enclaves have many sources of social support and resources. By contrast, others may be isolated, living apart from family, friends, and the support systems extant in their countries of origin. Culturally competent evaluation should always include questions about the client's country of origin, immigration status, length of time in the United States, and connections to his or her country of origin. Ask American-born clients about their parents' country of origin, the language(s) spoken at home, and affiliation with their parents' culture(s). Questions like these give the counselor important clues about the client's degree of acculturation in early life and at present, cultural identity, ties to culture of origin, potential cultural conflicts, and resources. Specific questions should elicit information about:

- Length of time in the United States, noting when immigration occurred or the number of generations who have resided in the United States.

- Frequency of returns and psychological and personal ties to the country of origin.

- Primary language and level of English proficiency in speaking and writing.

- Psychological reactions to immigration and adjustments made in the process.

- Changes in social status and other areas as a result of coming to this country.

- Major differences in attitudes toward alcohol and drug use from the time of immigration to now.

Advice to Counselors: Conducting Strength-Based Interviews

By nature, initial interviews and evaluations can overemphasize presenting problems and concerns while underplaying client strengths and supports. This list, although not exhaustive, reminds clinicians to acknowledge client strengths and supports from the outset.

Strengths and supports

- Pride and participation in one's culture

- Social skills, traditions, knowledge, and practical skills specific to the client's culture

- Bilingual or multilingual skills

- Traditional, religious, or spiritual practices, beliefs, and faith

- Generational wisdom

- Extended families and nonblood kinships

- Ability to maintain cultural heritage and practices

- Perseverance in coping with racism and oppression

- Culturally specific ways of coping

- Community involvement and support

Source: Hays 2008.

Cultural Identity and Acculturation

As shown in Zhang Min's case at the beginning of this chapter, cultural identity is a unique feature of each client. Counselors should guard against making assumptions about client identity based on general ethnic and racial identification by evaluating the degree to which an individual identifies with his or her culture(s) of origin. As Castro and colleagues (1999b) explain, “for each group, the level of within-group variability can be assessed using a core dimension that ranges from high cultural involvement and acceptance of the traditional culture's values to low or no cultural involvement” (p. 515). For African Americans, for example, this dimension is called “Afrocentricity.” Scales for Afrocentricity have been developed in an attempt to provide an indicator of an individual's level of involvement within the traditional or core African-oriented culture (Baldwin and Bell 1985; Cokley and Williams 2005; Klonoff and Landrine 2000). Many other instruments based on models of identity evaluate acculturation and identity. A detailed discussion of the theory behind such models is beyond the scope of this Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP); however, counselors should have a general understanding of what is being measured when administering such instruments. The “Asking About Culture and Acculturation” advice box at right addresses exploration of culture and acculturation with clients. For more information on instruments that measure acculturation and/or identity, see Appendix B.

Other areas to explore include the cross-cutting factors outlined in Chapter 1, such as socioeconomic status (SES), occupation, education, gender, and other variables that can distinguish an individual from others who share his or her cultural identity. For example, a biracial client could identify with African American culture, White American culture, or both. When a client has two or more racial/ethnic identities, counselors should assess how the client self-identifies and how he or she negotiates the different worlds.

Membership in a Subculture

Clients often identify initially with broader racial, ethnic, and cultural groups. However, each person has a unique history that warrants an understanding of how culture is practiced and has evolved for the person and his or her family; accordingly, counselors should avoid generalizations or assumptions. Clients are often part of a culture within a culture. There is not just one Latino, African American, or Native American culture; many variables influence culture and cultural identity (see the “What Are the Cross-Cutting Factors in Race, Ethnicity, and Culture” section in Chapter 1). For example, an African American client from East Carroll Parish, LA, might describe his or her culture quite differently than an African American from downtown Hartford, CT.

Beliefs About Health, Healing, Help-Seeking, and Substance Use

Just as culture shapes an individual's sense of identity, it also shapes attitudes surrounding health practices and substance use. Cultural acceptance of a behavior, for instance, can mask a problem or deter a person from seeking treatment. Counselors should be aware of how the client's culture conceptualizes issues related to health, healing and treatment practices, and the use of substances. For example, in cases where alcohol use is discouraged or frowned upon in the community, the client can experience tremendous shame about drinking. Chapter 5 reviews health-related beliefs and practices that can affect help-seeking behavior across diverse populations.

Trauma and Loss

Some immigrant subcultures have experienced violent upheavals and have a higher incidence of trauma than others. The theme of trauma and loss should therefore be incorporated into general intake questions. Specific issues under this general theme might include:

- Migration, relocation, and emigration history—which considers separation from homeland, family, and friends—and the stressors and loss of social support that can accompany these transitions.

- Clients' personal or familial experiences with American Indian boarding schools.

- Experiences with genocide, persecution, torture, war, and starvation.

Advice to Counselors: Eliciting Client Views on Presenting Problems

Some clients do not see their presenting physical, psychological, and/or behavioral difficulties as problems. Instead, they may view their presenting difficulties as the result of stress or another issue, thus defining or labeling the presenting problem as something other than a physical or mental disorder. In such cases, word the following questions using the clients' terminology rather than using the word “problem.” These questions help explore how clients view their behavioral health concerns:

- I know that clients and counselors sometimes have different ideas about illness and diseases, so can you tell me more about your idea of your problem?

- Do you consider your use of alcohol and/or drugs a problem?

- How do you label your problem? Do you think it is a serious problem?

- What do you think caused your problem?

- Why do you think it started when it did?

- What is going on in your body as a result of this problem?

- How has this problem affected your life?

- What frightens or concerns you most about this problem and its treatment?

- How is your problem viewed in your family? Is it acceptable?

- How is your problem viewed in your community? Is it acceptable? Is it considered a disease?

- Do you know others who have had this problem? How did they treat the problem?

- How does your problem affect your stature in the community?

- What kinds of treatment do you think will help or heal you?

- How have you treated your drug and/or alcohol problem or emotional distress?

- What has been your experience with treatment programs?

Sources: Lynch and Hanson 2011; Tang and Bigby 1996; Taylor 2002.

How To Use a Multicultural Intake Checklist

Some clients do not see their presenting physical, psychological, and/or behavioral difficulties as problems. Instead, they may view their presenting difficulties as the result of stress or another issue, thus defining or labeling the presenting problem as something other than a physical or mental disorder. In such cases, word questions about the following topics using the client's terminology, rather than using the word “problem.” Asking questions about the following topics can help you explore how a client may view his or her behavioral health concerns:

- □

Immigration history

- □

Relocations (current migration patterns)

- □

Losses associated with immigration and relocation history

- □

English language fluency

- □

Bilingual or multilingual fluency

- □

Individualistic/collectivistic orientation

- □

Racial, ethnic, and cultural identities

- □

Tribal affiliation, if appropriate

- □

Geographic location

- □

Family and extended family concerns (including nonblood kinships)

- □

Acculturation level (e.g., traditional, bicultural)

- □

Acculturation stress

- □

History of discrimination/racism

- □

Trauma history

- □

Historical trauma

- □

Intergenerational family history and concerns

- □

Gender roles and expectations

- □

Birth order roles and expectations

- □

Relationship and dating concerns

- □

Sexual and gender orientation

- □

Health concerns

- □

Traditional healing practices

- □

Help-seeking patterns

- □

Beliefs about wellness

- □

Beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment

- □

Beliefs about substance use, abuse, and dependence

- □

Beliefs about substance abuse treatment

- □

Family views on substance use and substance abuse treatment

- □

Treatment concerns related to cultural differences

- □

Cultural approaches to healing or treatment of substance use and mental disorders

- □

Education history and concerns

- □

Work history and concerns

- □

SES and financial concerns

- □

Cultural group affiliation

- □

Current network of support

- □

Community concerns

- □

Review of confidentiality parameters and concerns

- □

Cultural concepts of distress (DSM-5*)

- □

DSM-5 culturally related V-codes

Sources: Comas-Diaz 2012; Constantine and Sue 2005; Sussman 2004.

- *

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association [APA] 2013).

Step 5. Gather Culturally Relevant Collateral Information

A client who needs behavioral health treatment services may be unwilling or unable to provide a full personal history from his or her own perspective and may not recall certain events or be aware of how his or her behavior affects his or her well-being and that of others. Collateral information—supplemental information obtained with the client's permission from sources other than the client—can be derived from family members, medical and court records, probation and parole officers, community members, and others. Collateral information should include culturally relevant information obtained from the family, such as the organizational memberships, beliefs, and practices that shape the client's cultural identity and understanding of the world.

As families can be a vital source of information, counselors are likely to attain more support by engaging families earlier in the treatment process. Although counselor interactions with family members are often limited to a few formal sessions, the families of racially and ethnically diverse clients tend to play a more significant and influential role in clients' participation in treatment. Consequently, special sensitivity to the cultural background of family members providing collateral information is essential. Families, like clients, cannot be easily defined in terms of a generic cultural identity (Congress 2004; Taylor et al. 2012). Even families from the same racial background or ethnic heritage can be quite dissimilar, thus requiring a multidimensional approach in understanding the role of culture in the lives of clients and their families. Using the culturagram tool on the next page in preparation for counseling, treatment planning, or clinical supervision, clinicians can learn about the unique attributes and histories that influence clients' lives in a cultural context.

Step 6. Select Culturally Appropriate Screening and Assessment Tools

Discussions of the complexities of psychological testing, the interpretation of assessment measures, and the appropriateness of screening procedures are outside the scope of this TIP. However, counselors and other clinical service providers should be able to use assessment and screening information in culturally competent ways. This section discusses several instruments and their appropriateness for specific cultural groups. Counselors should continue to explore the availability of mental health and substance abuse screening and assessment tools that have been translated into or adapted for other languages.

Culturally Appropriate Screening Devices

The consensus panel does not recommend any specific instruments for screening or assessing mental or substance use disorders. Rather, when selecting instruments, practitioners should consider their cultural applicability to the client being served (AACE 2012; Jome and Moody 2002). For example, a screening instrument that asks the respondent about his or her guilt about drinking could be ineffective for members of cultural, ethnic, or religious groups that prohibit any consumption of alcohol. Al-Ansari and Negrete's (1990) research supports this point. They found that the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test was highly sensitive with people who use alcohol in a traditional Arab Muslim society; however, one question—“Do you ever feel guilty about your drinking?”—failed to distinguish between people with alcohol dependency disorders in treatment and people who drank in the community. Questions designed to measure conflict that results from the use of alcohol can skew test results for participants from cultures that expect complete abstinence from alcohol and/or drugs. Appendix D summarizes instruments tested on specific populations (e.g., availability of normative data for the population being served).

Culturally Valid Clinical Scales

As the literature consistently demonstrates, co-occurring mental disorders are common in people who have substance use disorders. Although an assessment of psychological problems helps match clients to appropriate treatment, clinicians are cautioned to proceed carefully. People who are abusing substances or experiencing withdrawal from substances can exhibit behaviors and thinking patterns consistent with mental illness. After a period of abstinence, symptoms that mimic mental illness can disappear. Moreover, clinical instruments are imperfect measurements of equally imperfect psychological constructs that were created to organize and understand clinical patterns and thus better treat them; they do not provide absolute answers. As research and science evolve, so does our understanding of mental illness (Benuto 2012). Assessment tools are generally developed for particular populations and can be inapplicable to diverse populations (Blume et al. 2005; Suzuki and Ponterotto 2008). Appendix D summarizes research on the clinical utility of instruments for screening and assessing co-occurring disorders in various cultural groups.

How To Use a Culturagram for Mapping the Role of Culture

The culturagram is an assessment tool that helps clinicians understand culturally diverse clients and their families (Congress 1994, 2004; Congress and Kung 2005). It examines 10 areas of inquiry, which should include not only questions specific to clients' life experiences, but also questions specific to their family histories. This diagram can guide an interview, counseling, or clinical supervision session to elicit culturally relevant multigenerational information unique to the client and the client's family. Give a copy of the diagram to the client or family for use as an interactive tool in the session. Throughout the interview, the client, family members, and/or the counselor can write brief responses in each box to highlight the unique attributes of the client's history in the family context. This diagram has been adapted for clients with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders; sample questions follow.

Values about family structure, power, myths, and rules

- Are there specific gender roles and expectations in your family?

- Who holds the power within the family?

- Are family needs more important than, or equally as important as, individual needs?

- Whom do you consider family?

Reasons for relocation or migration

- Are you and your family able to return home?

- What were your reasons for coming to the United States?

- How do you now view the initial reasons for relocation?

- What feelings do you have about relocation or migration?

- Do you move back and forth from one location to another?

- How often do you and your family return to your homeland?

- Are you living apart from your family?

Legal status and SES

- Has your SES improved or worsened since coming to this country?

- Has there been a change in socioeconomic status across generations?

- What is the family history of documentation? (Note: Clients often need to develop trust before discussing legal status; they may come from a place where confidentiality is unfamiliar.)

Time in the community

- How long have you and your family members been in the country? Community?

- Are you and your family actively involved in a culturally based community?

Languages spoken in and outside the home

- What languages are spoken at home and in the community?

- What is your and your family's level of proficiency in each language?

- How dependent are parents and grandparents on their children for negotiating activities surrounding the use of English? Have children become the family interpreters?

Health beliefs and beliefs about help-seeking

- What are the family beliefs about drug and alcohol use? Mental illness? Treatment?

- Do you and your family uphold traditional healing practices?

- How do help-seeking behaviors differ across generations and genders in your family?

- How do you and your family define illness and wellness?

- Are there any objections to the use of Western medicine?

Impact of trauma and other crisis events

- How has trauma affected your family across generations?

- How have traumas or other crises affected you and/or your family?

- Has there been a specific family crisis?

- Did the family experience traumatic events prior to migration—war, other forms of violence, displacement including refugee camps, or similar experiences?

Oppression and discrimination

- Is there a history of oppression and discrimination in your homeland?

- How have you and your family experienced discrimination since immigration?

Religious and cultural institutions, food, clothing, and holidays

- Are there specific religious holidays that your family observes?

- What holidays do you celebrate?

- Are there specific foods that are important to you?

- Does clothing play a significant cultural or religious role for you?

- Do you belong to a cultural or social club or organization?

Values about education and work

- How much importance do you place on work, family, and education?

- What are the educational expectations for children within the family?

- Has your work status changed (e.g., level of responsibility, prestige, and power) since migration?

- Do you or does anyone in your family work several jobs?

Sources: Comas-Diaz 2012; Congress 1994, 2004; Singer 2007.

Diagnosis

Counselors should consider clients' cultural backgrounds when evaluating and assessing mental and substance use disorders (Bhugra and Gupta 2010). Concerns surrounding diagnoses of mental and substance use disorders (and the cross-cultural applicability of those diagnoses) include the appropriateness of specific test items or questions, diagnostic criteria, and psychologically oriented concepts (Alarcon 2009; Room 2006). Research into specific techniques that address cultural differences in evaluative and diagnostic processes so far remains limited and underrepresentative of diverse populations (Guindon and Sobhany 2001; Martinez 2009).

Does the DSM-5 accurately diagnose mental and substance use disorders among immigrants and other ethnic groups? Caetano and Shafer (1996) found that diagnostic criteria seemed to identify alcohol dependency consistently across race and ethnicity, but their sample was limited to African Americans, Latinos, and Whites. Other research has shown mixed results.

In 1972, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) embarked on a joint study to test the cross-cultural applicability of classification systems for various diagnoses, including substance use disorders. WHO and NIH identified factors that appeared to be universal aspects of mental and substance use disorders and then developed instruments to measure them. These instruments, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) and the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN), include some DSM and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems criteria. Studies report that both the CIDI and SCAN were generally accurate, but the investigators urge caution in translation and interview procedures (Room et al. 2003).

Advice to Counselors and Clinical Supervisors: Culturally Responsive Screening and Assessment

- Assess the client's primary language and language proficiency prior to the administration of any evaluation or use of testing instruments.

- Determine whether the assessment materials were translated using specific terms, including idioms that correspond to the client's literacy level, culture, and language. Do not assume that translation into a stated language exactly matches the specific language of the client. Specifically, the client may not understand the translated language if it does not match his or her ways of thinking or speaking

- Educate the client on the purpose of the assessment and its application to the development of the treatment plan. Remember that testing can generate many emotional reactions.

- Know how the test was developed. Is normative data available for the population being served? Test results can be inflated, underestimated, or inaccurate due to differences within the client's population.

- Consider the role of acculturation in testing, including the influence of the client's worldview in responses. Unfamiliarity with mainstream United States culture can affect interpretation of questions, the client-evaluator relationship, and behavior, including participation level during evaluation and verbal and behavioral responses.

Sources: Association for Assessment in Counseling and Education (AACE) 2012; Saldaña 2001.

Overall, psychological concepts that are appropriate for and easily translated by some groups are inappropriate for others. In some Asian cultures, for example, feeling refers more to a physical than an emotive state; questions designed to infer emotional states are not easily translated. In most cases, these issues can be remedied by using culture-specific resources, measurements, and references while also adopting a cultural formulation in the interviewing process (see Appendix E for the A PA's cultural formulation outline). The DSM-5 lists several cultural concepts of distress (see Appendix E), yet there is little empirical literature providing data or treatment guidance on using the APA's cultural formulation or addressing cultural concepts of distress (Martinez 2009; Mezzich et al. 2009).

Step 7. Determine Readiness and Motivation for Change

Clients enter treatment programs at different levels of readiness for change. Even clients who present voluntarily could have been pushed into it by external pressures to accept treatment before reaching the action stage. These different readiness levels require different approaches. The strategies involved in motivational interviewing can help counselors prepare culturally diverse clients to change their behavior and keep them engaged in treatment. To understand motivational interviewing, it is first necessary to examine the process of change that is involved in recovery. See TIP 35, Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Abuse Treatment (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [CSAT] 1999b), for more information on this technique.

Stages of Change

Prochaska and DiClemente's (1984) classic transtheoretical model of change is applicable to culturally diverse populations. This model divides the change process into several stages:

- Precontemplation. The individual does not see a need to change. For example, a person at this stage who abuses substances does not see any need to alter use, denies that there is a problem, or blames the problem on other people or circumstances.

- Contemplation. The person becomes aware of a problem but is ambivalent about the course of action. For instance, a person struggling with depression recognizes that the depression has affected his or her life and thinks about getting help but remains ambivalent on how he/she may do this.

- Preparation. The individual has determined that the consequences of his or her behavior are too great and that change is necessary. Preparation includes small steps toward making specific changes, such as when a person who is overweight begins reading about wellness and weight management. The client still engages in poor health behaviors but may be altering some behaviors or planning to follow a diet.

- Action. The individual has a specific plan for change and begins to pursue it. In relation to substance abuse, the client may make an appointment for a drug and alcohol assessment prior to becoming abstinent from alcohol and drugs.

- Maintenance. The person continues to engage in behaviors that support his or her decision. For example, an individual with bipolar I disorder follows a daily relapse prevention plan that helps him or her assess warning signs of a manic episode and reminds him or her of the importance of engaging in help-seeking behaviors to minimize the severity of an episode.

Progress through the stages is nonlinear, with movement back and forth among the stages at different rates. It is important to recognize that change is not a one-time process, but rather, a series of trials and errors that eventually translates to successful change. For example, people who are dependent on substances often attempt to abstain several times before they are able to acquire long-term abstinence.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interventions assess a person's stage of change and use techniques likely to move the person forward in the sequence. Miller and Rollnick (2002) developed a therapeutic style called motivational interviewing, which is characterized by the strategic therapeutic activities of expressing empathy, developing discrepancy, avoiding argument, rolling with resistance, and supporting self-efficacy. The counselor's major tool is reflective listening and soliciting change talk (CSAT 1999c).

This nonconfrontational, client-centered approach to treatment differs significantly from traditional treatments in several ways, creating a more welcoming relationship. TIP 35 (CSAT 1999c) assesses Project MATCH and other clinical trials, concluding that the evidence strongly supports the use of motivational interviewing with a wide variety of cultural and ethnic groups (Miller and Rollnick 2013; Miller et al. 2008). TIP 35 is a good motivational interviewing resource. For specific application of motivational interviewing with Native Americans, see Venner and colleagues (2006). For improvement of treatment compliance among Latinos with depression through motivational interviewing, see Interian and colleagues (2010).

Step 8. Provide Culturally Responsive Case Management

Clients from various racial, ethnic, and cultural populations seeking behavioral health services may face additional obstacles that can interfere with or prevent access to treatment and ancillary services, compromise appropriate referrals, impede compliance with treatment recommendations, and produce poorer treatment outcomes. Obstacles may include immigration status, lower SES, language barriers, cultural differences, and lack of or poor coverage with health insurance.

Case management provides a single professional contact through which clients gain access to a range of services. The goal is to help assess the need for and coordinate social, health, and other essential services for each client. Case management can be an immense help during treatment and recovery for a person with limited English literacy and knowledge of the treatment system. Case management focuses on the needs of individual clients and their families and anticipates how those needs will be affected as treatment proceeds. The case manager advocates for the client (CSAT 1998a; Summers 2012), easing the way to effective treatment by assisting the client with critical aspects of life (e.g., food, childcare, employment, housing, legal problems). Like counselors, case managers should possess self-knowledge and basic knowledge of other cultures, traits conducive to working well with diverse groups, and the ability to apply cultural competence in practical ways.

Cultural competence begins with self-knowledge; counselors and case managers should be aware of and responsive to how their culture shapes attitudes and beliefs. This understanding will broaden as they gain knowledge and direct experience with the cultural groups of their client population, enabling them to better frame client issues and interact with clients in culturally specific and appropriate ways. TIP 27, Comprehensive Case Management for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT 1998a), offers more information on effective case management.

Exhibit 3-1 discusses the cultural matching of counselors with clients. When counselors cannot provide culturally or linguistically competent services, they must know when and how to bring in an interpreter or to seek other assistance (CSAT 1998a). Case management includes finding an interpreter who communicates well in the client's language and dialect and who is familiar with the vocabulary required to communicate effectively about sensitive subject matter. The case manager works within the system to ensure that the interpreter, when needed, can be compensated. Case managers should also have a list of appropriate referrals to meet assorted needs. For example, an immigrant who does not speak English may need legal services in his or her language; an undocumented worker may need to know where to go for medical assistance. Culturally competent case managers build and maintain rich referral resources for their clients.

Exhibit 3-1

Client-Counselor Matching.

The Case Management Society of America's Standards of Practice for Case Management (2010) state that case management is central in meeting client needs throughout the course of treatment. The standards stress understanding relevant cultural information and communicating effectively by respecting and being responsive to clients and their cultural contexts. For standards that are also applicable to case management, refer to the National Association of Social Workers' Standards on Cultural Competence in Social Work Practice (2001).

Step 9. Incorporate Cultural Factors Into Treatment Planning

The cultural adaptation of treatment practices is a burgeoning area of interest, yet research is limited regarding the process and outcome of culturally responsive treatment planning in behavioral health treatment services for diverse populations. How do counselors and organizations respond culturally to the diverse needs of clients in the treatment planning process? How effective are culturally adaptive treatment goals? (For a review, see Bernal and Domenech Rodriguez 2012.) Typically, programs that provide culturally responsive services approach treatment goals holistically, including objectives to improve physical health and spiritual strength (Howard 2003). Newer approaches stress implementation of strength-based strategies that fortify cultural heritage, identity, and resiliency.

Treatment planning is a dynamic process that evolves along with an understanding of the clients' histories and treatment needs. Foremost, counselors should be mindful of each client's linguistic requirements and the availability of interpreters (for more detail on interpreters, see Chapter 4). Counselors should be flexible in designing treatment plans to meet client needs and, when appropriate, should draw upon the institutions and resources of clients' cultural communities. Culturally responsive treatment planning is achieved through active listening and should consider client values, beliefs, and expectations. Client health beliefs and treatment preferences (e.g., purification ceremonies for Native American clients) should be incorporated in addressing specific presenting problems. Some people seek help for psychological concerns and substance abuse from alternative sources (e.g., clergy, elders, social supports). Others prefer treatment programs that use principles and approaches specific to their cultures. Counselors can suggest appropriate traditional treatment resources to supplement clinical treatment activities.

In sum, clinicians need to incorporate culture-based goals and objectives into treatment plans and establish and support open client–counselor dialog to get feedback on the proposed plan's relevance. Doing so can improve client engagement in treatment services, compliance with treatment planning and recommendations, and treatment outcomes.

Group Clinical Supervision Case Study

Beverly is a 34-year-old White American who feels responsible for the tension and dissension in her family. Beverly works in the lab of an obstetrics and gynecology practice. Since early childhood, her younger brother has had problems that have been diagnosed differently by various medical and mental health professionals. He takes several medications, including one for attention deficit disorder. Beverly's father has been out of work for several months. He is seeing a psychiatrist for depression and is on an antidepressant medication. Beverly's mother feels burdened by family problems and ineffective in dealing with them. Beverly has always helped her parents with their problems, but she now feels bad that she cannot improve their situation. She believes that if she were to work harder and be more astute, she could lessen her family's distress. She has had trouble sleeping. In the past, she secretly drank in the evenings to relieve her tension and anxiety.

Most counselors agree that Beverly is too submissive and think assertiveness training will help her put her needs first and move out of the family home. However, a female Asian American counselor sees Beverly's priorities differently, saying that “a morally responsible daughter is duty-bound to care for her parents.” She thinks that the family needs Beverly's help, so it would be selfish to leave them.

Discuss

- How does the counselor's worldview affect prioritizing the client's presenting problems?

- How does the counselor's individualistic or collectivistic culture affect treatment planning?

- How might a counselor approach the initial interview and evaluation to minimize the influence of his or her worldview in the evaluation and treatment planning process?

Sources: The Office of Nursing Practice and Professional Services, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health & Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto 2008; Zhang 1994.

- Engage Clients

- Familiarize Clients and Their Families With Treatment and Evaluation Processes

- Endorse Collaboration in Interviews, Assessments, and Treatment Planning

- Integrate Culturally Relevant Information and Themes

- Gather Culturally Relevant Collateral Information

- Select Culturally Appropriate Screening and Assessment Tools

- Determine Readiness and Motivation for Change

- Provide Culturally Responsive Case Management

- Incorporate Cultural Factors Into Treatment Planning

- Culturally Responsive Evaluation and Treatment Planning - Improving Cultural Com...Culturally Responsive Evaluation and Treatment Planning - Improving Cultural Competence

- Mus musculus adult male hypothalamus cDNA, RIKEN full-length enriched library, c...Mus musculus adult male hypothalamus cDNA, RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:A230035L05 product:hypothetical Divalent cation transporter containing protein, full insert sequencegi|26332640|dbj|AK038549.1|Nucleotide

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...