2.2. The Health System

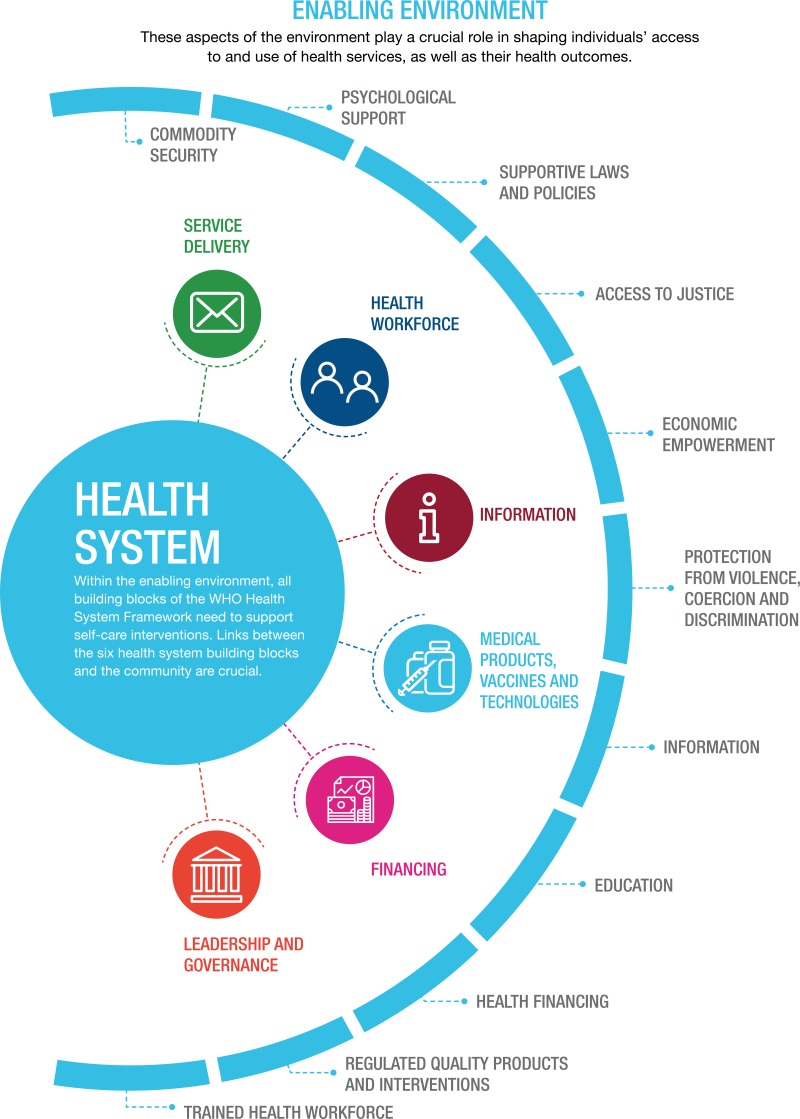

Self-care interventions must be an adjunct to, rather than a replacement for, direct interaction with the health system, and this may require reconceptualizing the boundaries of the health system. Users’ experiences of self-care interventions are shaped, in part, by the health system. To be safe and effective, and to reach individuals who may not be able to access health care, self-care interventions may need more – not less – support from the health system (1). Drawing on the WHO Health System Framework (2), every health system “building block” (see ) needs to be adapted to ensure its adequacy for effective self-care interventions.

The WHO Health System Framework. Source: WHO, 2007 (2).

In addition, there will be an increased need to reach out to communities to ensure that people have appropriate information about self-care interventions to make informed choices about using them, and that they seek support from health workers as needed. This is further explored in section 2.2.7, with the potential users of self-care interventions placed at the centre of all considerations relating to how the health system might have to respond.

2.2.1. Service delivery

Service provision or delivery is a direct function of the inputs into the health system, such as the health workforce, procurement/supplies, and financing: increased inputs should lead to improved service delivery and enhanced access to services. Ensuring availability of and access to health services that meet or exceed the minimum quality standards are key functions of a health system (3). Services are organized around the person’s needs and preferences, not the disease or the person’s ability to pay. Users perceive health services as being responsive and acceptable to them (or not) and this promotes an approach where people are active partners in their own health care. Service delivery is organized to provide an individual with continuity of care across the network of services, health conditions, levels of care, and over the life course.

2.2.2. The health workforce

The forthcoming WHO global competency framework for universal health coverage (UHC) will cover health interventions across promotive, preventative, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services, which can be provided by health professionals and community health workers at the primary health care level with a pre-service training pathway of 12–48 months (4). The framework will focus on the competencies (integrated knowledge, skills and behaviours) required to provide interventions, and will have relevance to both pre-service and in-service education and training. In order to maximize the opportunities to promote and facilitate self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), it is important that training for health workers incorporates: communication to enable informed decision-making; values clarification; interprofessional teamworking; and empathetic and compassionate approaches to care.

Delivery of care and treatment services should be accomplished in a people-centred and nonjudgemental way, allowing everyone to lead the decision-making about their own care in an informed and supported fashion. Self-care interventions, even if accessed and used outside health services, require some engagement with the health system and, as such, it is critical that the attitudes and behaviours of health workers be inclusive and non-stigmatizing, and that they promote safety, including patient safety and equality. Health-care providers and managers of health-care facilities – whether in the public or private sector – are responsible for delivering services appropriately and meeting standards based on professional ethics and internationally agreed human rights principles. Health workers also need to acknowledge that people have always and will continue to practise self-care that is not initiated by the health system.

2.2.3. Information

Health information and services must be available and accessible at the time and place they are needed, and they must also be acceptable and of high quality. With self-care interventions available outside the health system, potential users must have access to reliable, useful, quality information that is consistent with the needs of the individual and the community. Additionally, pictures and visuals are useful in overcoming language barriers and literacy issues. Mobile phones, tablets and other information and communications technologies (ICTs) are providing new opportunities to deliver health information. There may be a need to devise different ways of providing information to populations with diverse needs and different levels of literacy that connects them back to the health system as appropriate.

Health information should be available to and used by health workers to address clinical and non-clinical aspects of self-care for SRHR. Information should be reliable and accurate, and it needs to be trusted by individuals, who rely on it to support their informed decision-making about their personal health and well-being and about their interactions with the health system. For example, patient information leaflets are a legal requirement in many countries, and they must be designed to ensure that patients who rely on the information provided can make informed decisions about the safe and effective use of the products and interventions described. Capturing information about self-care interventions may require the expansion of health management information systems (HMIS) beyond the traditional confines of the health system.

2.2.4. Medical products, vaccines and technologies

The sequence of processes to guarantee access to appropriate and safe medical products, vaccines and technologies includes health technology regulation, assessment and management (see ) (5). The national (i.e. government) regulatory authorities determine which medical products, vaccines and technologies can enter the local market. Necessary medical products and technologies must be made available to allow for the uninterrupted delivery of services and implementation of interventions; this includes supplies that might be accessed outside of traditional health services (e.g. through pharmacies or online). Even though most self-care interventions are likely to be used outside the health-care setting, the quality of the products and technologies must be appropriately regulated (see section 2.2.6).

Reproductive health commodity security (RHCS) exists when every person is able to choose, obtain and use quality contraceptives and other essential reproductive health products whenever they need them. As demand for reproductive health supplies increases, countries are under increasing pressure to establish and maintain secure systems for procuring reproductive health commodities

Sequence of Processes to Guarantee Access to Appropriate and Safe Medical Devices. Source: adapted from WHO, 2017 (6).

and managing their delivery. RHCS involves planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of supply chain processes at the programme level, as well as broader policy advocacy, management of procurement issues, devising costing strategies, multi-sectoral coordination and addressing contextual considerations. Enabling and strengthening in-country capacity for RHCS is an essential step in guarding against shortfalls in much-needed reproductive health supplies (

7).

2.2.5. Financing

Using self-care approaches and technologies to deliver certain health-care interventions could affect: (i) how much societies pay for delivering these interventions (and producing the associated health outcomes); (ii) who pays for these interventions; and (iii) who accesses them (8). A critical consideration for equity is that self-care should not be promoted as a means of saving costs for the health system by shifting costs to users. For example, if users have to obtain test kits or other devices or supplies to access an intervention which would otherwise be paid for by the health system if accessed within health services, then wherever possible these costs should remain with the health system and not be transferred to the user. Benefit packages and risk-pooling mechanisms may have to be designed to support those accessing self-care interventions in a range of settings and to ensure financial protection. Since UHC aims to ensure equitable and sustainable access to an essential package of quality care (see further information on UHC in Box 5.3 in section 5.3), there may be scope for differentiated financing models that include a combination of government subsidies, private financing, insurance coverage and partial out-of-pocket payments, based on the principle of progressive universalism. Budgetary allocations and financing strategies need to be recognized for the critical role they play in creating the enabling environment for people to use self-care interventions to help achieve good health outcomes, contributing to UHC and promoting cost-effective service delivery. Health systems must also consider the potential savings that may result from earlier diagnosis and treatment due to self-care, and include these in the financial equation.

2.2.6. Leadership/governance – the regulatory environment

With self-care interventions encompassing many different products and places of access, regulation of a wide range of actors is necessary. Regulation of self-care interventions should be aligned with human rights laws and obligations and be sensitive to the relevant differences among interventions and among users, as well as across the diversity of locations where these interventions are purchased and used. It is likely that, as self-care interventions become increasingly available through the private sector and online, informal and/or unregulated vendors might supply products of unknown quality, safety and performance (9). Regulation is key in this context, and it is critical to balance ensuring quality and safety against restricting access. Detection and correction of any undesirable trends and distortions – i.e. any negative impacts or unintended uses of self-care interventions – is also important. The regulatory system also has a role to play to identify and prevent the spread of counterfeit products. Finally, transparent, accessible and effective accountability mechanisms must be put in place; these may operate alongside other social accountability mechanisms, but there must be avenues for remedy, redress and access to justice through the health system (10, 11).

2.2.7. Links between health systems and communities

In the context of self-care interventions, bridges between health systems and communities take on unprecedented importance for ensuring safe, informed and appropriate use of these interventions. This should include outreach to provide information on self-care interventions as well as the traditional/standard options available, and how and where to seek support from health services as and when required, including outreach to communities who may be unaware of new technological advances in self-care products.

Safe and effective provision of self-care interventions requires that mechanisms be put into place to overcome any barriers to service uptake, use and continued engagement with the health system. These barriers occur at the individual, interpersonal, community and societal levels. They may include challenges such as social exclusion

Characteristics of the Enabling Environment to Shape Access to and Use of Self-Care Interventions.

and marginalization, criminalization, stigma, gender-based violence and gender inequality, among others. Strategies are needed across health system building blocks (see ) to improve the availability, accessibility, acceptability, affordability, uptake, equitable coverage, quality, effectiveness and efficiency of self-care interventions as well as links to services. Left unaddressed, such barriers could undermine health, even where self-care interventions are available; removing these barriers is a critical part of creating an enabling environment for self-care interventions.

2.3. Enabling Environment

The environment within which the health system is situated and the individual resides plays a crucial role in shaping individuals’ access to and use of health services, as well as their health outcomes (). This is particularly true for self-care interventions, many of which are accessed and/or used outside health services (1). This environment must, therefore, be conducive to the realization of SRHR for all. The importance of the social determinants of SRHR, as manifested in laws, institutional arrangements and social practices that prevent individuals from effectively enjoying their SRHR, has been well documented (12).

2.3.1. Access to justice

Policies and procedures are needed to ensure that all people can safely report rights violations, such as discrimination, violations of medical confidentiality and denial of health services. Programmes should facilitate the same level of access to justice for individuals using self-care interventions. Primary considerations in facilitating access to justice must include safety, confidentiality, choice and autonomy in terms of whether or not an individual wants to report the violation experienced. A functional system of remedy and redress should be accessible to users; in the case of rights violations (e.g. discrimination), such a system provides a mechanism for seeking legal redress, through which users can hold duty-bearers, including health workers, accountable for their actions or inactions. Where appropriate, health-care providers should facilitate access to justice by offering to support clients who want to report violations to the police.

2.3.2. Economic empowerment

Livelihood insecurity, poverty and a lack of resources to meet key needs and expenses contribute to greater vulnerability and poor SRHR outcomes. Socioeconomic vulnerabilities can make it difficult for people to exercise their SRHR, such as in situations where individuals are dependent on violent or abusive partners, or transactional sex, to ensure that their own and/or their children’s basic needs are met. There is a risk that self-care interventions might shift the costs of care from the health system to the individual (see section 2.2.5). This could exacerbate inequities in terms of access to these interventions. Therefore, interventions focused on economic empowerment, poverty reduction and resource access, such as housing and food support, have the potential to improve access to health care and improve health outcomes for all.

2.3.3. Education

Education, particularly secondary education, is important for empowering people in relation to their SRHR, and has repeatedly been found to be associated with a wide range of better sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes as well as improved knowledge of how to maintain good health (13, 14). The central role of comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) in empowering young people to take responsible and informed decisions about their sexuality and relationships is also well documented (15). Ensuring access to education, including CSE, for all will support informed decision-making with regard to self-care interventions and associated care seeking.

2.3.4. Protection from violence, coercion and discrimination

Violence can take various forms, including physical aggression, forced or coerced sexual contact, and psychological abuse, as well as controlling behaviours by an intimate partner (16). Multiple structural factors influence vulnerability to violence, including discriminatory or harsh laws and policing practices, and cultural and social norms that legitimize stigma and discrimination (16, 17). Violence may undermine people’s ability to make and enact health-promoting decisions related to their sexual and reproductive life, or to access and utilize SRH services, including self-care interventions. Further, the negative psychological outcomes of violence may inhibit self-care (18). The potential risks of violence associated with the use of self-care interventions must be considered and mitigated.

Efforts to address violence in this context must involve other sectors along with the health sector. While appropriate action around violence could help improve SRHR for everyone, special attention should be paid to people who may be more vulnerable to stigma, exclusion and violence, including people living with HIV as well as sexual and gender minorities, people who use drugs and people engaged in sex work.

2.3.5. Psychosocial support

Psychosocial support (see definition in Annex 4: Glossary) helps individuals and communities to heal psychological wounds and rebuild social structures after an emergency or a critical event. It can help change people into active survivors rather than passive victims. Early and adequate psychosocial support can: (i) prevent distress and suffering developing into something more severe; (ii) help people cope better and become reconciled to everyday life; (iii) help beneficiaries to resume their normal lives; and (iv) meet community-identified needs (19).

2.3.6. Supportive laws and policies

The legal and policy environment shapes the availability of health services and programmes as well as the degree to which they are responsive to individuals’ needs and aspirations. Laws and public policies are also key tools with which to influence social and economic context – they can reinforce positive social determinants and begin the process of addressing those social norms or conditions that exacerbate health inequity (20). The barriers created by, for example, criminalization of adult, consensual sexual conduct and other behaviours, as well as third-party authorization for accessing services, should be addressed. If these barriers persist, linkage to health services following the use of self-care interventions will continue to be impeded. In addition, the regulation required to promote access to self-care interventions without compromising quality or safety is a critical area for action to realize SRHR.

Social Determinants and the Environment Itself:

Access to and use of health services are shaped by the environment in which both the individual and health system are situated. It is important that the environment is conducive to care providing access, coverage, quality and safety.