All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: tni.ohw@sredrokoob). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html).

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children: Guidelines for the Management of Common Childhood Illnesses. 2nd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children: Guidelines for the Management of Common Childhood Illnesses. 2nd edition.

Show detailsThis chapter gives treatment guidelines for the management of the most important conditions for which children aged between 2 months and 5 years present with fever. Management of febrile conditions in young infants (< 2 months) is described in Chapter 3.

6.1. Child presenting with fever

6.1.1. Fever lasting 7 days or less

Special attention should be paid to children presenting with fever. The main aim is to differentiate serious, treatable infections from mild self-resolving febrile illness.

History

- duration of fever

- residence in or recent travel to an area with malaria transmission

- recent contact with a person with an infectious disease

- vaccination history

- skin rash

- stiff neck or neck pain

- headache

- convulsions or seizures

- pain on passing urine

- ear pain.

Examination

For details see Tables 16–19.

- General: drowsiness or altered consciousness, pallor or cyanosis, or lymphadenopathy

- Head and neck: bulging fontanel, stiff neck, discharge from ear or red, immobile ear-drum on otoscopy, swelling or tenderness in mastoid region

- Chest: fast breathing (pneumonia, septicaemia or malaria)

- Abdomen: enlarged spleen (malaria) or enlarged liver

- Limbs: difficulty in moving joint or limb (abscess, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, rheumatic fever)

- Skin rash

- –

Pustules, or signs of infection: red, hot, swollen, tender (staphylococcal infection)

- –

Haemorrhagic rash: purpura, petaechiae (meningococcal infection, dengue)

- –

Maculopapular rash (measles, other viral infections)

Table 16Differential diagnosis of fever without localizing signs

| Diagnosis | In favour |

|---|---|

| Malaria (in endemic area) |

|

| Septicaemia |

|

| Typhoid |

|

| Urinary tract infection |

|

| Fever associated with HIV infection |

|

Table 17Differential diagnosis of fever with localized signs

| Diagnosis | In favour |

|---|---|

| Meningitis |

|

| Otitis media |

|

| Mastoiditis |

|

| Osteomyelitis |

|

| Septic arthritis |

|

| Acute rheumatic fever |

|

| Skin and soft tissue infection |

|

| Pneumonia (see 4.2 and 4.3 for other clinical findings) |

|

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection |

|

| Retropharyngeal abscess |

|

| Sinusitis |

|

| Hepatitis |

|

Table 18Differential diagnosis of fever with rash

| Diagnosis | In favour |

|---|---|

| Measles |

|

| Viral infections |

|

| Relapsing fever |

|

| Typhusa |

|

| Dengue haemorrhagic feverb |

|

- a

In some regions, other rickettsial infections may be relatively common.

- b

In some regions, the presentation of other viral haemorrhagic fevers is similar to that of dengue.

Table 19Additional differential diagnoses of fever lasting longer than 7 days

| Diagnosis | In favour |

|---|---|

| Abscess |

|

| Salmonella infection (non-typhoidal) |

|

| Infective endocarditis |

|

| Rheumatic fever |

|

| Miliary TB |

|

| Brucellosis (local knowledge of prevalence is important) |

|

| Borreliosis (relapsing fever) (local knowledge of prevalence important) |

|

Laboratory investigations

- oxygen saturation

- blood smear

- urine microscopy and culture

- full blood count

- lumbar puncture if signs suggest meningitis

- blood culture

Differential diagnosis

The four major categories of fever in children are:

- due to infection, with non-localized signs (Table 16)

- due to infection, with localized signs (Table 17)

- with rash (Table 18)

- lasting longer than 7 days.

These categories overlap to some extent. Some causes of fever are found only in certain regions (e.g. malaria, dengue haemorrhagic fever, relapsing fever). Other fevers may be seasonal (e.g. malaria, meningococcal meningitis) or occur in epidemics (measles, dengue, meningococcal meningitis, typhus).

6.1.2. Fever lasting longer than 7 days

As there are many causes of prolonged fever, it is important to know the commonest causes in a given area. Investigations to determine the most likely cause can then be started and treatment decided. Sometimes there is need for a ‘trial of treatment’, e.g. for highly suspected TB or Salmonella infections; improvement supports the suspected diagnosis.

History

Take a history, as for fever. In addition, consider the possibility of HIV, TB or malignancy, which can cause persistent fever.

Examination

Fully undress the child, and examine the whole body for the following signs:

- fast breathing or chest indrawing (pneumonia)

- stiff neck or bulging fontanel (meningitis)

- red tender joint (septic arthritis or rheumatic fever)

- fast breathing or chest indrawing (pneumonia or severe pneumonia)

- petaechial or purpuric rash (meningococcal disease or dengue)

- maculopapular rash (viral infection or drug reaction)

- inflamed throat and mucous membranes (throat infection)

- red, painful ear with immobile ear-drum (otitis media)

- jaundice or anaemia (malaria, hepatitis, leptospirosis or septicaemia)

- painful spine, hips or other joints (septic arthritis)

- tender abdomen (suprapubic or loin in urinary tract infection)

Some causes of persistent fever may have no localizing diagnostic signs, such as septicaemia, Salmonella infections, miliary TB, HIV infection or urinary tract infection.

Laboratory investigations

When available, perform the following:

- blood films or rapid diagnostic test for malaria parasites (a positive test in an endemic area does not exclude other, co-existing causes of fever)

- full blood count, including platelet count, and examination of a thin film for cell morphology

- urinalysis, including microscopy

Mantoux test (Note: often negative in a child who has miliary TB, severe malnutrition or HIV infection)

- chest X-ray

- blood culture

- HIV testing (if the fever has lasted > 30 days and there is reason to suspect HIV infection)

- lumbar puncture (to exclude meningitis if there are suggestive signs).

6.2. Malaria

6.2.1. Severe malaria

Severe malaria, which is usually due to Plasmodium falciparum, is a life-threatening condition. The illness starts with fever and often vomiting. Children can deteriorate rapidly over 1–2 days, developing complications, the commonest of which are coma (cerebral malaria) or less profound altered level of consciousness, inability to sit up or drink (prostration), convulsions, severe anaemia, respiratory distress (due to acidosis) and hypoglycaemia.

Diagnosis

History. Children with severe malaria present with some of the clinical features listed below. A change of behaviour, confusion, drowsiness, altered consciousness and generalized weakness are usually indicative of ‘cerebral malaria’.

Examination. Make a rapid clinical assessment, with special attention to level of consciousness, blood pressure, rate and depth of respiration and pallor. Assess neck stiffness and examine for rash to exclude alternative diagnoses. The main features indicative of severe malaria are:

- generalized multiple convulsions: more than two episodes in 24 h

- impaired consciousness, including unrousable coma

- generalized weakness (prostration) or lethargy, i.e. the child is unable walk or sit up without assistance

- deep laboured breathing and respiratory distress (acidotic breathing)

- pulmonary oedema (or radiological evidence)

- abnormal bleeding

- clinical jaundice plus evidence of other vital organ dysfunction

- severe pallor

- circulatory collapse or shock with systolic blood pressure < 50 mm Hg

- haemoglobinuria (dark urine)

Laboratory findings. Children with the following findings on investigation have severe malaria:

- hypoglycaemia (blood glucose < 2.5 mmol/litre or < 45 mg/dl). Check blood glucose in all children with signs suggesting severe malaria.

- hyperparasitaemia (thick blood smears and thin blood smear if species identification required). Hyperparasitaemia > 100 000/μl (2.5%) in low-intensity transmission areas or 20% hyperparasitaemia in areas of high transmission. Where microscopy is not feasible or may be delayed, a positive rapid diagnostic test is diagnostic.

- severe anaemia (eryththrocyte volume fraction [EVF], < 15%; Hb, < 5 g/dl)

- high blood lactate (> 5 mmol/litre)

- high serum creatinine (renal impairment, creatinine >265 umol/l)

- lumbar puncture to exclude bacterial meningitis in a child with severe malaria and altered level of consciousness or in coma. A lumbar puncture should be done if there are no contraindications. If lumbar puncture is delayed and bacterial meningitis cannot be excluded, give antibiotic treatment in addition to antimalarial treatment.

If severe malaria is suspected and the initial blood smear is negative, perform a rapid diagnostic test, if available. If the test is positive, treat for severe malaria but continue to look for other causes of severe illness (including severe bacterial infections). If the rapid diagnostic test is negative, malaria is unlikely to be the cause of illness, and an alternative diagnosis must be sought.

Treatment

Emergency measures, to be taken within the first hour

- ►

If the child is unconscious, minimize the risk for aspiration pneumonia by inserting a nasogastric tube and removing the gastric contents by suction. Keep the airway open, and place in recovery position.

- ►

Check for hypoglycaemia and correct, if present. If blood glucose cannot be measured and hypoglycaemia is suspected, give glucose.

- ►

Treat convulsions with rectal or IV diazepam (see Chart 9). Do not give prophylactic anticonvulsants.

- ►

Start treatment with an effective antimalarial agent (see below).

- ►

If hyperpyrexia is present, give paracetamol or ibuprofen to reduce temperature below 39 °C.

- ►

Check for associated dehydration, and treat appropriately if present (see fluid balance disturbances).

- ►

Treat severe anaemia.

- ►

Institute regular observation of vital and neurological signs.

Antimalarial treatment

If confirmation of malaria from a blood smear or rapid diagnostic test is likely to take more than 1 h, start antimalarial treatment before the diagnosis is confirmed.

Parenteral artesunate is the drug of choice for the treatment of severe P. falciparum malaria. If it is not available, parenteral artemether or quinine should be used. Give antimalarial agents by the parenteral route until the child can take oral medication or for a minimum of 24 h even if the patient can tolerate oral medication earlier.

- ►

Artesunate: Give artesunate at 2.4 mg/kg IV or IM on admission, then at 12 h and 24 h, then daily until the child can take oral medication but for a minimum of 24 h even if the child can tolerate oral medication earlier.

- ►

Quinine: Give a loading dose of quinine dihydrochloride salt at 20 mg/kg by infusion in 10 ml/kg of IV fluid over 2–4 h. Then, 8 h after the start of the loading dose, give 10 mg/kg quinine salt in IV fluid over 2 h, and repeat every 8 h until the child can take oral medication. The infusion rate should not exceed a total of 5 mg/kg per h of quinine dihydrochloride salt.

IV quinine should never be given as a bolus injection but as a 2–4 h infusion under close nursing supervision. If IV quinine infusion is not possible, quinine dihydrochloride can be given as a diluted divided IM injection. Give the loading dose split into two as 10 mg/kg of quinine salt into the anterior aspect of each thigh. Then, continue with 10 mg/kg every 8 h until oral medication is tolerated. The diluted parenteral solution is better absorbed and less painful.

- ►

Artemether: Give artemether at 3.2 mg/kg IM on admission, then 1.6 mg/kg daily until the child can take oral medication. Use a 1-ml tuberculin syringe to give the small injection volume. As absorption of artemether may be erratic, it should be used only if artesunate or quinine is not available.

Give parenteral antimalarial agent for the treatment of severe malaria for at least 24 h; thereafter, complete treatment with a full course of artemisinin-based combination therapy, such as:

- artemether–lumefantrine

- artesunate plus amodiaquine

- artesunate plus sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine,

- dihydroartemisinin plus piperaquine.

Supportive care

- Ensure meticulous nursing care, especially for unconscious patients.

- Ensure that they receive daily fluid requirements, and monitor fluid status carefully by keeping a careful record of fluid intake and output.

- Feed children unable to feed for more than 1–2 days by nasogastric tube, which is preferable to prolonged IV fluids.

- Avoid giving any harmful drugs like corticosteroids, low-molecular-mass dextran and other anti-inflammatory drugs.

Dehydration

Examine frequently for signs of dehydration or fluid overload, and treat appropriately. The most reliable sign of fluid overload is an enlarged liver. Additional signs are gallop rhythm, fine crackles at lung bases and fullness of neck veins when upright. Eyelid oedema is a useful sign of fluid overload.

If, after careful rehydration, the urine output over 24 h is < 4 ml/kg, give IV furosemide, initially at 2 mg/kg. If there is no response, double the dose at hourly intervals to a maximum of 8 mg/kg (given over 15 min). Large doses should be given once to avoid possible nephrotoxicity.

For an unconscious child

- ►

Maintain clear airway.

- ►

Nurse the child in recovery position or 30° head-up to avoid aspiration of fluids.

- ►

Insert a nasogastric tube for feeding and to minimize the risk of aspiration.

- ►

Turn the patient every 2 h.

- Do not allow the child to lie in a wet bed.

- Pay attention to pressure points.

Complications

Coma (cerebral malaria)

The earliest symptom of cerebral malaria is usually a brief (1–2-day) history of fever, followed by inability to eat or drink preceding a change in behaviour or altered level of consciousness. In children with cerebral malaria:

- Assess, monitor and record the level of consciousness according to the AVPU or another locally used coma scale for children.

- Exclude other treatable causes of coma (e.g. hypoglycaemia, bacterial meningitis). Always exclude hypoglycaemia by checking blood glucose; if this is not possible, treat for hypoglycaemia. Perform a lumbar puncture if there are no contraindications. If you cannot do a lumbar puncture to exclude meningitis, give antibiotics for bacterial meningitis (see section 6.3).

- Monitor all other vital signs (temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure and urine output).

- Manage convulsions if present.

Convulsions

Convulsions are common before and after the onset of coma. They may be very subtle, such as intermittent nystagmus, twitching of a limb, a single digit or a corner of the mouth, or an irregular breathing pattern.

- ►

Give anticonvulsant treatment with rectal diazepam or slow IV injection (see Chart 9).

- Check blood glucose to exclude hypoglycaemia, and correct with IV glucose if present; if blood glucose cannot be measured, treat for hypoglycaemia.

- ►

If there are repeated convulsions, give phenobarbital (see Chart 9).

- ►

If temperature is ≥ 39 °C, give a dose of paracetamol.

Shock

Some children may already be in shock, with cold extremities (clammy skin), weak rapid pulse, capillary refill longer than 3 s and low blood pressure. These features may indicate complicating septicaemia, although dehydration may also contribute to the hypotension.

- Correct hypovolaemia as appropriate.

- Take blood for culture

- Do urinalysis.

- ►

Give both antimalarial and antibiotic treatment for septicaemia (see section 6.5).

Severe anaemia

Severe anaemia is indicated by severe palmar pallor, often with a fast pulse rate, difficult breathing, confusion or restlessness. Signs of heart failure such as gallop rhythm, enlarged liver and, rarely, pulmonary oedema (fast breathing, fine basal crackles on auscultation) may be present

- ►

Give a blood transfusion as soon as possible to:

- –

all children with an EVF ≤ 12% or Hb ≤ 4 g/dl.

- –

less severely anaemic children (EVF > 12–15%; Hb 4–5 g/dl) with any of the following:

- shock or clinically detectable dehydration

- impaired consciousness

- respiratory acidosis (deep, laboured breathing)

- heart failure

- very high parasitaemia (> 20% of red cells parasitized).

- ►

Give 10 ml/kg packed cells or 20 ml/kg whole blood over 3–4 h.

- –

A diuretic is not usually indicated, because many of these children are usually hypovolaemic with a low blood volume.

- –

Check the respiratory rate and pulse rate every 15 min. If one of them rises, transfuse more slowly. If there is any evidence of fluid overload due to the blood transfusion, give IV furosemide (1–2 mg/kg) up to a maximum total of 20 mg.

- –

After the transfusion, if the Hb remains low, repeat the transfusion.

- –

In severely malnourished children, fluid overload is a common and a serious complication. Give whole blood (10 ml/kg rather than 20 ml/kg) once only and do not repeat the transfusion.

- ►

Give a daily iron–folate tablet or iron syrup for 14 days.

Hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia (blood glucose < 2.5 mmol/litre or < 45 mg/dl) is particularly common in children < 3 years, especially those with convulsions or hyperparasitaemia and who are comatose. It is easily overlooked because the clinical signs may mimic cerebral malaria. Hypoglycaemia should be corrected if glucose is < 3 mmol/l (54 mg/dl).

- ►

Give 5 ml/kg of 10% glucose (dextrose) solution IV rapidly (see Chart 10). If IV access is not possible, place an intraosseous needle (see p. 340) or give sublingual sugar solution. Recheck the blood glucose after 30 min, and repeat the dextrose (5 ml/kg) if the level is low (< 3.0 mmol/l; < 54 mg/dl).

Prevent further hypoglycaemia in an unconscious child by giving 10% dextrose in normal saline or Ringer's lactate for maintenance infusion (add 20 ml of 50% glucose to 80 ml of 0.9% normal saline or Ringer's lactate). Do not exceed the maintenance fluid requirements for the child's weight (see section 10.2).

Monitor blood glucose and signs of fluid overload. If the child develops fluid overload and blood glucose is still low, stop the infusion; repeat 10% glucose (5 ml/kg), and feed the child by nasogastric tube as appropriate.

Once the child can take food orally, stop IV treatment and feed the child by nasogastric tube. Breastfeed every 3 h, if possible, or give milk feeds of 15 ml/kg if the child can swallow. If the child cannot feed without risk of aspiration, especially if the gag reflex is still absent, give sugar solution or small feeds by nasogastric tube (see Chart 10). Continue monitoring blood glucose, and treat accordingly (as above) if it is < 2.5 mmol/litre or < 45 mg/dl.

Respiratory distress (acidosis)

Respiratory distress presents as deep, laboured breathing, while the chest is clear on auscultation, often accompanied by lower chest wall indrawing. It is commonly caused by systemic metabolic acidosis (frequently lactic acidosis). It may develop in a fully conscious child but more often occurs in children with an altered level of consciousness, prostration, cerebral malaria, severe anaemia or hypoglycaemia. Respiratory distress due to acidosis must be distinguished from that caused by pneumonia (including history of aspiration) or pulmonary oedema due to fluid overload. If acidosis is present:

- Give oxygen.

- Correct reversible causes of acidosis, especially dehydration and severe anaemia:

- –

If Hb is ≥ 5 g/dl, give 20 ml/kg normal saline or Ringer's lactate (Hartmann's solution) IV over 30 min.

- –

If Hb is < 5 g/dl, give whole blood (10 ml/kg) over 30 min and a further 10 ml/kg over 1–2 h without diuretics. Check the respiratory rate and pulse rate every 15 min. If either shows any rise, transfuse more slowly to avoid precipitating pulmonary oedema (see guidelines on blood transfusion, section 10.6).

- ►

Monitor response by continuous clinical observation (oxygen saturation, Hb, packed cell volume, blood glucose and acid–base balance if available)

Aspiration pneumonia

Treat aspiration pneumonia immediately, as it can be fatal.

- Place the child on his or her side or at least 30° head-up.

- Give oxygen if oxygen saturation is ≤ 90% or, if you cannot do pulse oximetry, if there is cyanosis, severe lower chest wall indrawing or a respiratory rate ≥ 70/min.

- Give IV ampicillin and gentamicin for a total of 7 days.

Monitoring

The child should be checked by a nurse at least every 3 h and by a doctor at least twice a day. The IV infusion rate should be checked hourly. Children with cold extremities, hypoglycaemia on admission, respiratory distress and/or deep coma are at greatest risk of death and must be kept under very close observation.

- Monitor and report immediately any change in the level of consciousness, convulsions or the child's behaviour.

- Monitor temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate (and, if possible, blood pressure) every 6 h for at least the first 48 h.

- Monitor the blood glucose level every 3 h until the child is fully conscious.

- Check the IV infusion rate regularly. If available, use a chamber with a volume of 100–150 ml. Avoid over-infusion of fluids from a 500-ml or 1-litre bottles or bags, especially if the child is not supervised all the time. Partially empty the IV bottle or bag to reduce the amount before starting the infusion. If the risk of over-infusion cannot be ruled out, it is safer to rehydrate or feed through a nasogastric tube.

- Keep a careful record of fluid intake (including IV infusions) and output.

6.2.2. Uncomplicated malaria

The presentation of uncomplicated malaria is highly variable and may mimic many other causes of fever.

Diagnosis

The child has:

- fever (temperature ≥ 37.5°C or ≥ 99.5 °F) or history of fever

- a positive blood smear or positive rapid diagnostic test for malaria

- no signs of severe malaria:

- –

altered consciousness

- –

severe anaemia (EVF < 15% or Hb < 5 g/dl)

- –

hypoglycaemia (blood glucose < 2.5 mmol/litre or < 45 mg/dl)

- –

respiratory distress

- –

jaundice

Note: If a child in a malarious area has fever with no obvious cause and it is not possible to confirm malaria on a blood film or with a rapid diagnostic test, treat the child for malaria.

Treatment

Treat with a first-line antimalarial agent, as in the national guidelines, with one of the following recommended regimens:

Uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria: Treat for 3 days with one of the recommended artemisinin-based combination therapy options:

- ►

Artemether–lumefantrine: combined tablets containing 20 mg of artemether and 120 mg of lumefantrine:

Dosage for combined tablet:

- child weighing 5 – < 15 kg: one tablet twice a day for 3 days

- child weighing 15–24 kg: 2 tablets twice a day for 3 days

- child > 25 kg: 3 tablets twice a day for 3 days

- ►

Artesunate plus amodiaquine: a fixed-dose formulation in tablets containing 25/67.5 mg, 50/135 mg or 100/270 mg of artesunate/amodiaquine.

Dosage for combined tablet:

- Aim for a target dose of 4 mg/kg per day artesunate and 10 mg/kg per day amodiaquine once a day for 3 days.

- child weighing 3 – < 10 kg: one tablet (25 mg/67.5 mg) twice a day for 3 days

- child weighing 10–18 kg: one tablet (50 mg/135 mg) twice a day for 3 days.

- ►

Artesunate plus sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine. Separate tablets of 50 mg artesunate and 500 mg sulfadoxine–25 mg pyrimethamine:

Dosage:

- Aim for a target dose of 4 mg/kg per day artesunate once a day for 3 days and 25 mg/kg sulfadoxine – 1.25 mg/kg pyrimethamine on day 1.

Artesunate:

- child weighing 3 – < 10 kg: half tablet once daily for 3 days

- child weighing ≥ 10 kg: one tablet once daily for 3 days

Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine:

- child weighing 3 – < 10 kg: half tablet once on day 1

- child weighing ≥ 10 kg: one tablet once on day 1

- ►

Artesunate plus mefloquine. Separate tablets of 50 mg artesunate and 250 mg mefloquine base:

Dosage:

Aim for a target dose of 4 mg/kg per day artesunate once a day for 3 days and 25 mg/kg of mefloquine divided into two or three doses.

- ►

Dihydroartemisinin plus piperaquine. Fixed-dose combination in tablets containing 40 mg dihydroartemisinin and 320 mg piperaquine.

Dosage:

Aim for a target dose of 4 mg/kg per day dihydroartemisinin and 18 mg/kg per day piperaquine once a day for 3 days.

Dosage of combined tablet:

- Child weighing 5 – < 7 kg: half tablet (20 mg/160 mg) once a day for 3 days

- Child weighing 7 – < 13 kg: one tablet (20 mg/160 mg) once a day for 3 days

- Child weighing 13 – < 24 kg: one tablet (320 mg/40 mg) once a day for 3 days

Children with HIV infection: Give prompt antimalarial treatment as recommended above. Patients on zidovudine or efavirenz should, however, avoid amodiaquine-containing artemisinin-based combination therapy, and those on co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim plus sulfamethoxazole) prophylaxis should avoid sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine.

Uncomplicated P. vivax, ovale and malariae malaria: Malaria due to these organisms is still sensitive to 3 days' treatment with chloroquine, followed by primaquine for 14 days. For P. vivax, treatment with artemisinin-based combination therapy is also recommended.

- ►

For P. vivax, give a 3-day course of artemisinin-based combination therapy as recommended for P. falciparum (with the exception of artesunate plus sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine) combined with primaquine at 0.25 mg base/kg, taken with food once daily for 14 days.

- ►

Give oral chloroquine at a total dose of 25 mg base/kg, combined with primaquine.

Dosage:

- Chloroquine at an initial dose of 10 mg base/kg, followed by 10 mg/kg on the second day and 5 mg/kg on the third day.

- Primaquine at 0.25 mg base/kg, taken with food once daily for 14 days.

- ►

Chloroquine-resistant vivax malaria should be treated with amodiaquine, mefloquine or dihydroartemisinin plus piperaquine as the drugs of choice.

Complications

Anaemia

In any child with palmar pallor, determine the Hb or EVF. Hb of 5–9.3 g/dl (equivalent to approximately 15–27%) indicates moderate anaemia. Begin treatment with iron and folate immediately after completion of antimalarial treatment or on discharge (omit iron for any child with severe malnutrition until recovery).

- ►

Give a daily iron–folate tablet or iron syrup for 14 days).

- Ask the parent to return with the child in 14 days. Treat for 3 months, as it takes 2–4 weeks to correct anaemia and 1–3 months to build up iron stores.

- ►

If the child is > 1 year and has not received mebendazole in the previous 6 months, give one dose of mebendazole (500 mg) for possible hookworm or whipworm infestation.

- ►

Advise the mother about good feeding practice.

Palmar pallor: sign of anaemia

Follow-up

If the child is treated as an outpatient, ask the mother to return if the fever persists after 3 days' treatment, or sooner if the child's condition gets worse. If the child returns, check if the child actually took the full dose of treatment and repeat a blood smear. If the treatment was not taken, repeat it. If it was taken but the blood smear is still positive, treat with a second-line antimalarial agent. Reassess the child to exclude the possibility of other causes of fever (see section 6.1.

If the fever persists after 3 days of treatment with the second-line antimalarial agent, ask the mother to return with the child to assess other causes of fever.

6.3. Meningitis

Early diagnosis is essential for effective treatment. This section refers to children and infants > 2 months. For diagnosis and treatment of meningitis in young infants, see section 3.9.

6.3.1. Bacterial meningitis

Bacterial meningitis is a serious illness that is responsible for considerable morbidity and mortality. No single clinical feature emerges as sufficiently distinctive to make a robust diagnosis, but a history of fever and seizures with the presence of meningeal signs and altered consciousness are common features of meningitis. The possibility of viral encephalitis or tuberculous meningitis must be considered as differential diagnoses in children with meningeal signs.

Diagnosis

Look for a history of:

- convulsions

- vomiting

- inability to drink or breastfeed

- a headache or pain in back of neck

- irritability

- a recent head injury

On examination, look for:

- altered level of consciousness

- neck stiffness

- repeated convulsions

- bulging fontanelle in infants

- non-blanching petaechial rash or purpura

- lethargy

- irritability

- evidence of head trauma suggesting possible recent skull fracture.

Also look for any of the following signs of raised intracranial pressure:

- decreased consciousness level

- unequal pupils

- rigid posture or posturing

- focal paralysis in any of the limbs

- irregular breathing

Looking and feeling for stiff neck in a child

Unequal pupil size: sign of raised intracranial pressure

Opisthotonus and rigid posture: sign of meningeal irritation and raised intracranial pressure

Laboratory investigations

- Confirm the diagnosis with a lumbar puncture and examination of the CSF. If the CSF is cloudy, assume meningitis and start treatment while waiting for laboratory confirmation.

- Microscopy should indicate the presence of meningitis in the majority of cases with a white cell (polymorph) count < 100/mm3. Confirmation can be obtained from CSF glucose (low: < 1.5 mmol/litre or a ratio of CSF to serum glucose of ≤ 0.4), CSF protein (high: > 0.4 g/litre) and Gram staining and culture of CSF, where possible.

- Blood culture if available.

Precaution: If there are signs of increased intracranial pressure, the potential value of the information from a lumbar puncture should be carefully weighed against the risk of the procedure. If in doubt, it might be better to start treatment for suspected meningitis and delay performing a lumbar puncture.

Treatment

Start treatment with antibiotics immediately before the results of laboratory CSF examination if meningitis is clinically suspected or the CSF is obviously cloudy. If the child has signs of meningitis and a lumbar puncture is not possible, treat immediately.

Antibiotic treatment

- ►

Give antibiotic treatment as soon as possible. Choose one of the following regimens:

- Ceftriaxone: 50 mg/kg per dose IM or IV every 12 h; or 100 mg/kg once daily for 7–10 days administered by deep IM injection or as a slow IV injection over 30–60 min.or

- Cefotaxime: 50 mg/kg per dose IM or IV every 6 h for 7–10 days.or

- When there is no known significant resistance to chloramphenicol and β -lactam antibiotics among bacteria that cause meningitis, follow national guidelines or choose either of the following two regimens:

- Chloramphenicol: 25 mg/kg IM or IV every 6 h plus ampicillin: 50 mg/kg IM or IV every 6 h for 10 daysor

- Chloramphenicol: 25 mg/kg IM or IV every 6 h plus benzylpenicillin: 60 mg/kg (100 000 U/kg) every 6 h IM or IV for 10 days.

- ►

Review therapy when CSF results are available.

If the diagnosis is confirmed, continue with parenteral antibiotics to complete treatment as above. Once the child has improved, continue with daily injections of third-generation cephalosporins to complete treatment, or, if on chloramphenicol, give orally, unless there is concern about oral absorption (e.g. in severely malnourished children or in those with diarrhoea), in which cases the full treatment should be given parenterally.

If there is a poor response to treatment:

- –

Consider the presence of common complications, such as subdural effusions (persistent fever plus focal neurological signs or reduced level of consciousness) or a cerebral abscess. If these are suspected, refer the child to a hospital with specialized facilities for further management (see a standard paediatrics textbook for details of treatment).

- –

Look for other sites of infection that may be the cause of fever, such as cellulitis at injection sites, arthritis or osteomyelitis.

Repeat the lumbar puncture after 3–5 days if fever is still present and the child's overall condition is not improving, and look for evidence of improvement (e.g. fall in leukocyte count and rise in glucose level).

Steroid treatment

Steroids offer some benefit in certain cases of bacterial meningitis (H. influenza, tuberculous and pneumococcal) by reducing the degree of inflammation and improving outcome. The recommended dexamethasone dose in bacterial meningitis is 0.15 mg/kg every 6 h for 2–4 days. Steroids should be given within 10–20 min before or during administration of antibiotics. There is insufficient evidence to recommend routine use of steroids in all children with bacterial meningitis in developing countries, except in tuberculous meningitis.

Do not use steroids in:

- newborns

- suspected cerebral malaria

- suspected viral encephalitis

Antimalarial treatment

In malarious areas, take a blood smear or do a rapid diagnostic test to check for malaria, as severe malaria should be considered a differential diagnosis or co-existing condition.

- ►

Treat with an appropriate antimalarial drug if malaria is diagnosed. If for any reason a blood smear cannot be taken, treat presumptively for malaria.

6.3.2. Meningococcal epidemics

During a confirmed epidemic of meningococcal meningitis, lumbar punctures need not be performed for all children who have petaechial or purpuric signs, which are characteristic of meningococcal infection.

- For children aged 0–23 months, treatment should be adapted according to the patient's age, and an effort should be made to exclude any other cause of meningitis.

- For children aged ≥ 2–5 years, Neisseria meningitidis is the most likely pathogen and presumptive treatment is justified.

- ►

Give ceftriaxone at 100 mg/kg/day IM or IV once daily for 5 days to children aged 2 months to 5 years or for at least 7 days to children aged 0–2 months.

or

- ►

Give oily chloramphenicol (100 mg/kg IM as a single dose up to a maximum of 3 g). If no improvement after 24 h, give a second dose of 100 mg/kg, or change to ceftriaxone as above. The oily chloramphenicol suspension is thick and may be difficult to push through the needle. If this problem is encountered, the dose can be divided into two and an injection given into each buttock of the child.

6.3.3. Tuberculous meningitis

Tuberculous meningitis may have an acute or chronic presentation, with the duration of presenting symptoms varying from 1 day to 9 months. It may present with cranial nerve deficits, or it may have a more indolent course involving headache, meningismus and altered mental status. The initial symptoms are usually nonspecific, including headache, vomiting, photophobia and fever. Consult up-to-date international and national guidelines for further details if tuberculous meningitis is suspected. Consider tuberculous meningitis if any of the following is present:

- Fever has persisted for 14 days.

- Fever has persisted for > 7 days, and a family member has TB.

- A chest X-ray suggests TB.

- The patient is unconscious and remains so despite treatment for bacterial meningitis.

- The patient is known to have HIV infection or is exposed to HIV.

- The CSF has a moderately high white blood cell count (typically < 500 white cells per ml, mostly lymphocytes), elevated protein (0.8–4 g/l) and low glucose (< 1.5 mmol/litre), or this pattern persists despite adequate treatment for bacterial meningitis.

Occasionally, when the diagnosis is not clear, a trial of treatment for tuberculous meningitis is added to treatment for bacterial meningitis. Consult national TB programme guidelines.

Treatment: The optimal treatment regimen comprises:

- ►

Four-drug regimen (HRZE) for 2 months, followed by a two-drug regimen (HR) for 10 months, the total duration of treatment being 12 months.

- –

Isoniazid (H): 10 mg/kg (range, 10–15 mg/kg); maximum dose, 300 mg/day

- –

Rifampicin (R): 15 mg/kg (range, 10–20 mg/kg); maximum dose, 600 mg/kg per day

- –

Pyrazinamide (Z): 35 mg/kg (range, 30–40 mg/kg)

- –

Ethambutol (E): 20 mg/kg (range, 15–25 mg/kg)

- ►

Dexamethasone (0.6 mg/kg per day for 2–3 weeks, reducing the dose over a further 2–3 weeks) should be given in all cases of tuberculous meningitis.

- ►

Children with proven or suspected tuberculous meningitis caused by MDR bacilli can be treated with a fluoroquinolone and other second-line drugs in the context of a well-functioning MDR TB control programme and within an appropriate MDR TB regimen. The decision to treat should be taken by a clinician experienced in managing paediatric TB.

Note: Streptomycin is not advised for children as it may cause otoxicity and nephrotoxicity, and the injections are painful.

6.3.4. Cryptococcal meningitis

Consider cryptococcal meningitis in older children known or suspected to be HIV-positive with immunosuppression. Children will present with meningitis with altered mental status.

- Perform a lumbar puncture. The opening pressure may be elevated, but CSF cell count, glucose and protein may be virtually normal.

- Analyse CSF with India ink preparation, or, if available, do a rapid CSF cryptococcal antigen latex agglutination test or lateral flow assay.

Treatment: A combination of amphotericin and fluconazole.

Supportive care

Examine all children with convulsions for hyperpyrexia and check blood glucose. Control fever if high (≥ 39 °C or ≥ 102.2 °F) with paracetamol, and treat hypoglycaemia.

- ►

Convulsions: If convulsions occur, give anticonvulsant treatment with intravenous or rectal diazepam (see Chart 9). Treat repeated convulsions with a preventive anticonvulsant, such as phenytoin or phenobarbitone.

- ►

Hypoglycaemia: Monitor blood glucose regularly, especially in children who are convulsing or not feeding well.

- –

If hypoglycaemia is present, give 5 ml/kg of 10% glucose (dextrose) solution IV or intraosseusly rapidly (see Chart 10). Recheck the blood glucose after 30 min. If the level is low (< 2.5 mmol/litre or < 45 mg/dl), repeat the glucose (5 ml/kg). If blood glucose cannot be measured, treat all children who are fitting or have reduced consciousness for hypoglycaemia.

- –

Prevent further hypoglycaemia by oral feeding (see above). If the child is not feeding, prevent hypoglycaemia by adding 10 ml of 50% glucose to 90 ml of Ringer's lactate or normal saline infusion. Do not exceed maintenance fluid requirements for the child's weight (see section 10.2). If the child develops signs of fluid overload, stop the infusion and feed by nasogastric tube.

- ►

Unconscious child: In an unconscious child, ensure that the airway is open at all times and that the patient is breathing adequately.

- Maintain clear airway.

- Nurse the child in the recovery position to avoid aspiration of fluids.

- Turn the patient every 2 h.

- Do not allow the child to lie in a wet bed.

- Pay attention to pressure points.

- ►

Oxygen treatment: Give oxygen if the child has convulsions or associated severe pneumonia with hypoxia (oxygen saturation ≤ 90% by pulse oximetry), or, if the child has cyanosis, severe lower chest wall indrawing, respiratory rate > 70/min. Aim to keep oxygen saturation > 90% (see section 10.7).

- ►

Fluid and nutritional management: Although children with bacterial meningitis are at risk for developing brain oedema due to a syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion or fluid overload, under-hydration may also lead to cerebral hypoperfusion. Correct dehydration if present. Some children with meningitis require only 50–75% of their normal daily fluid requirement IV in the first 2 days to maintain normal fluid balance; more will cause oedema. Avoid fluid overload, ensure an accurate record of intake and output, and examine frequently for signs of fluid overload (eyelid oedema, enlarged liver, crackles at lung bases or fullness of neck veins).

Give due attention to acute nutritional support and rehabilitation. Feed the child as soon as it is safe. Breastfeed every 3 h, if possible, or give milk feeds of 15 ml/kg if the child can swallow. If there is a risk of aspiration, it is safer to continue with IV fluids; otherwise, feed by nasogastric tube (see Chart 10). Continue to monitor blood glucose, and treat accordingly (as above) if < 2.5 mmol/litre or < 45 mg/dl.

Monitoring

A nurse should monitor the child's state of consciousness and vital signs (respiratory rate, heart rate and pupil size) every 3 h during the first 24 h (thereafter, every 6 h), and a doctor should monitor the child at least twice a day.

At the time of discharge, assess all children for neurological problems, especially hearing loss. Measure and record the head circumference of infants. If there is neurological damage, refer the child for physiotherapy, and give the mother suggestions for simple passive exercises.

Complications

Complications may occur during the acute phase of the disease or as long-term neurological sequelae:

- Acute phase complications: Convulsions are common, and focal convulsions are more likely to be associated with neurological sequelae. Other acute complications may include shock (see section 1.5.2), hyponatraemia and subdural effusions, which may lead to persistent fever.

- Long-term complications: Some children have sensory hearing loss, motor or development problems and epilepsy.

Follow-up

Sensorineural deafness is common after meningitis. Arrange a hearing assessment for all children 1 month after discharge from hospital.

Public health measures

In meningococcal meningitis epidemics, advise families of the possibility of secondary cases in the household so that they report for treatment promptly. Chemoprophylaxis should be considered only for those in close contact with people with meningococcal infection.

6.4. Measles

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease with serious complications (such as blindness in children with pre-existing vitamin A deficiency) and high mortality. It is rare in infants < 3 months of age.

Diagnosis

Diagnose measles if the child has:

- fever (sometimes with a febrile convulsion) and

- a generalized maculopapular rash and

- one of the following: cough, runny nose or red eyes.

Corneal clouding: sign of xerophthalamia in vitamin A-deficient child (left side) in comparison with the normal eye (right side)

In children with HIV infection, some of these signs may not be present, and the diagnosis of measles may be difficult.

6.4.1. Severe complicated measles

Diagnosis

In a child with evidence of measles (as above), any one of the following symptoms and signs indicates the presence of severe complicated measles:

- inability to drink or breastfeed

- vomits everything

- convulsions

On examination, look for signs of complications, such as:

- lethargy or unconsciousness

- corneal clouding

- deep or extensive mouth ulcers

- pneumonia (see section 4.2)

- dehydration from diarrhoea (see section 5.2)

- stridor due to measles croup

- severe malnutrition

Distribution of measles rash

The left side of the drawing shows the early rash covering the head and upper part of the trunk; the right side shows the later rash covering the whole body.

Treatment

Children with severe complicated measles require treatment in hospital.

- ►

Vitamin A therapy. Give oral vitamin A to all children with measles, unless the child has already had adequate vitamin A treatment for this illness as an outpatient. Give oral vitamin A at 50 000 IU (for a child aged < 6 months), 100 000 IU (6–11 months) or 200 000 IU (1–5 years). If the child shows any eye sign of vitamin A deficiency, give a third dose 2–4 weeks after the second dose on follow-up.

Supportive care

Fever

- ►

If the child's temperature is ≥ 39 °C (≥ 102.2 °F) and is causing distress, give paracetamol.

Nutritional support

Assess the nutritional status by weighing the child and plotting the weight on a growth chart (rehydrate before weighing). Encourage continued breastfeeding. Encourage the child to take frequent small meals. Check for mouth ulcers and treat them, if present (see below). Follow the guidelines on nutritional management given in Chapter 10.

Complications

Follow the guidelines given in other sections of this manual for the management of the following complications:

- Pneumonia: Give antibiotics for pneumonia to all children with measles and signs of pneumonia, as over 50% of all cases of pneumonia in measles have secondary bacterial infection (section 4.2.

- Otitis media.

- ►

Diarrhoea: Treat dehydration, bloody diarrhoea or persistent diarrhoea (see Chapter 5).

- ►

Measles croup (see section 4.6.1): Give supportive care. Do not give steroids.

- ►

Eye problems. Conjunctivitis and corneal and retinal damage may occur due to infection, vitamin A deficiency or harmful local remedies. In addition to giving vitamin A (as above), treat any infection present. If there is a clear watery discharge, no treatment is needed. If there is pus discharge, clean the eyes with cotton-wool boiled in water or a clean cloth dipped in clean water. Apply tetracycline eye ointment three times a day for 7 days. Never use steroid ointment. Use a protective eye pad to prevent other infections. If there is no improvement, refer to an eye specialist.

- ►

Mouth ulcers. If the child can drink and eat, clean the mouth with clean, salted water (a pinch of salt in a cup of water) at least four times a day.

- –

Apply 0.25% gentian violet to sores in the mouth after cleaning.

- –

If the mouth ulcers are severe and/or smelly, give IM or IV benzylpenicillin (50 000 U/kg every 6 h) and oral metronidazole (7.5 mg/kg three times a day) for 5 days.

- –

If the mouth sores result in decreased intake of food or fluids, the child may require feeding via a nasogastric tube.

- ►

Neurological complications. Convulsions, excessive sleepiness, drowsiness or coma may be symptoms of encephalitis or severe dehydration. Assess the child for dehydration and treat accordingly (see section 5.2). See Chart 9, for treatment of convulsions and care of an unconscious child.

- ►

Severe acute malnutrition: See guidelines in Chapter 7.

Monitoring

Take the child's temperature twice a day, and check for the presence of the above complications daily.

Follow-up

Recovery after acute measles is often delayed for many weeks and even months, especially in children who are malnourished. Arrange for the child to receive the third dose of vitamin A before discharge, if this has not already been given.

Public health measures

If possible, isolate children admitted to hospital for measles for at least 4 days after the onset of the rash. Ideally, they should be kept in a separate ward from other children. For malnourished and immunocompromised children, isolation should be continued throughout the illness.

When there are measles cases in the hospital, vaccinate all other children > 6 months of age (including those seen as outpatients, admitted in the week after a measles case and HIV-positive children). If infants aged 6–9 months receive measles vaccine, it is essential that the second dose be given as soon as possible after 9 months of age.

Check the vaccination status of hospital staff and vaccinate, if necessary.

6.4.2. Non-severe measles

Diagnosis

Diagnose non-severe measles in a child whose mother clearly reports that the child has had a measles rash, or if the child has:

- fever and

- a generalized rash and

- one of the following: cough, runny nose or red eyes, but

- none of the features of severe measles (see section 6.4.1).

Treatment

- ►

Treat as an outpatient.

- ►

Vitamin A therapy. Check whether the child has already been given adequate vitamin A for this illness. If not, give 50 000 IU (if aged < 6 months), 100 000 IU (6–11 months) or 200 000 IU (1–5 years).

Supportive care

- ►

Fever. If the child's temperature is ≥ 39 °C (≥ 102.2 °F) and is causing distress or discomfort, give paracetamol.

- ►

Nutritional support. Assess the nutritional status by measuring the mid upper arm circumference (MUAC). Encourage the mother to continue breastfeeding and to give the child frequent small meals. Check for mouth ulcers and treat, if present (see above).

- ►

Eye care. For mild conjunctivitis with only a clear watery discharge, no treatment is needed. If there is pus, clean the eyes with cotton-wool boiled in water or a clean cloth dipped in clean water. Apply tetracycline eye ointment three times a day for 7 days. Never use steroid ointment.

- ►

Mouth care. If the child has a sore mouth, ask the mother to wash the mouth with clean, salted water (a pinch of salt in a cup of water) at least four times a day. Advise the mother to avoid giving salty, spicy or hot foods to the child.

Follow-up

Ask the mother to return with the child in 2 days to see whether the mouth or eye problems are resolving, to exclude any severe complications and to monitor nutrition and growth.

6.5. Septicaemia

Septicaemia should be considered in a child with acute fever who is severely ill, when no other cause is found. Septicaemia can also occur as a complication of meningitis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection or any other bacterial infection. The common causative agents include Streptococcus, Haemophilus influenza, Staphylococcus aureus and enteric Gram-negative bacilli (which are common in severe malnutrition), such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella. Non-typhoidal Salmonella is a common cause in malarious areas. Where meningococcal disease is common, a clinical diagnosis of meningococcal septicaemia can be made if petaechiae or purpura (haemorrhagic skin lesions) are present.

Diagnosis

The child's history helps determine the likely source of sepsis. Always fully undress the child and examine carefully for signs of local infection before deciding that there is no other cause.

On examination, look for:

- fever with no obvious focus of infection

- negative blood film for malaria

- no stiff neck or other specific sign of meningitis, or negative lumbar puncture for meningitis

- confusion or lethargy

- signs of systemic upset (e.g. inability to drink or breastfeed, convulsions, lethargy or vomiting everything, tachypnoea)

- Purpura may be present.

Investigations

The investigations will depend on presentation but may include:

- full blood count

- urinalysis (including urine culture)

- blood culture

- chest X-rays.

In some severe cases, a child may present with signs of septic shock: cold hands with poor peripheral perfusion and increased capillary refill time (> 3 s), fast, weak pulse volume, hypotension and decreased mental status.

Treatment

Start the child immediately on antibiotics.

- ►

Give IV ampicillin at 50 mg/kg every 6 h plus IV gentamicin 7.5 mg/kg once a day for 7–10 days; alternatively, give ceftriaxone at 80–100 mg/kg IV once daily over 30–60 min for 7–10 days.

- ►

When staphylococcal infection is strongly suspected, give flucloxacillin at 50 mg/kg every 6 h IV plus IV gentamicin at 7.5 mg/kg once a day.

- ►

Give oxygen if the child is in respiratory distress or shock.

- ►

Treat septic shock with rapid IV infusion of 20 ml/kg of normal saline or Ringer's lactate. Reassess. If the child is still in shock, repeat 20 ml/kg of fluid up to 60 ml/kg. If the child is still in shock (fluid-refractory shock), start adrenaline or dopamine if available.

Supportive care

- ►

If the child has a high fever (≥ 39 °C or 102.2 °F) that is causing distress or discomfort, give paracetamol or ibuprofen.

- ►

Monitor Hb or EVF, and, when indicated, give a blood transfusion of 20 ml/kg fresh whole blood or 10 ml/kg of packed cells, the rate of infusion depending on the circulatory status.

Monitoring

- ►

The child should be checked by a nurse at least every 3 h and by a doctor at least twice a day. Check for the presence of new complications, such as shock, cyanosis, reduced urine output, signs of bleeding (petaechiae, purpura, bleeding from venepuncture sites) or skin ulceration.

- ►

Monitor Hb or EVF. If they are low and falling, weigh the benefits of transfusion against the risk for bloodborne infection (see section 10.6).

6.6. Typhoid fever

Consider typhoid fever if a child presents with fever and any of the following: constipation, vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, cough, transient rash, particularly if the fever has persisted for ≥ 7 days and malaria has been excluded.

Diagnosis

On examination, the main diagnostic features of typhoid are:

- fever with no obvious focus of infection

- no stiff neck or other specific sign of meningitis, or negative lumbar puncture for meningitis (Note: children with typhoid can occasionally have a stiff neck)

- signs of systemic upset, e.g. inability to drink or breastfeed, convulsions, lethargy, disorientation or confusion, or vomiting everything

- Pink spots on the abdominal wall may be seen in light-skinned children.

- hepatosplenomegaly, tender or distended abdomen

Typhoid fever can present atypically in young infants as an acute febrile illness with shock and hypothermia. In areas where typhus is common, it may be difficult to distinguish between typhoid fever and typhus by clinical examination alone (See standard paediatrics textbook for diagnosis of typhus).

Treatment

- ►

Treat with oral ciprofloxacin at 15 mg/kg twice a day or any other fluoroquinolone (gatifloxacin, ofloxacin, perfloxacin) as first-line treatment for 7–10 days.

- ►

If the response to treatment is poor after 48 h, consider drug-resistant typhoid, and treat with second-line antibiotic. Give IV ceftriaxone at 80 mg/kg per day or oral azithromycin at 20 mg/kg per day or any other third-generation cephalosporin for 5–7 days.

- ►

Where drug resistance to antibiotics among Salmonella isolates is known, follow the national guidelines on local susceptibility.

Supportive care

- ►

If the child has high fever (≥ 39 °C or ≥ 102.2 °F) that is causing distress or discomfort, give paracetamol.

Monitoring

The child should be checked by a nurse at least every 3 h and by a doctor at least twice a day.

Complications

Complications of typhoid fever include convulsions, confusion or coma, diarrhoea, dehydration, shock, cardiac failure, pneumonia, osteomyelitis and anaemia. In young infants, shock and hypothermia can occur.

Acute gastrointestinal perforation with haemorrhage and peritonitis can occur, usually presenting as severe abdominal pain, vomiting, abdominal tenderness on palpation, severe pallor and shock. Abdominal examination may show an abdominal mass due to abscess formation and an enlarged liver and/or spleen.

If there are signs of gastrointestinal perforation, pass an IV line and nasogastric tube, start appropriate fluids, and obtain urgent surgical attention.

6.7. Ear infections

6.7.1. Mastoiditis

Mastoiditis is a bacterial infection of the mastoid bone behind the ear. Without treatment it can lead to meningitis and brain abscess.

Diagnosis

Key diagnostic features are:

- high fever

- tender swelling behind the ear.

Treatment

- ►

Give IV or IM cloxacillin or flucloxacillin at 50 mg/kg every 6 h or ceftriaxone until the child improves, for a total course of 10 days.

- ►

If there is no response to treatment within 48 h or the child's condition deteriorates, refer the child to a surgical specialist to consider incision and drainage of mastoid abscesses or mastoidectomy.

- ►

If there are signs of meningitis or brain abscess, give antibiotic treatment as outlined in section 6.3, and, if possible, refer to a specialist hospital immediately.

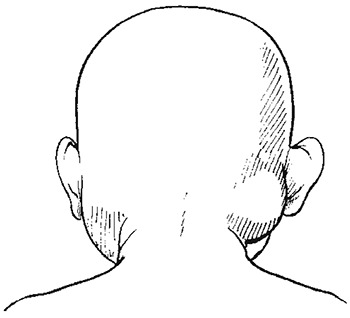

Mastoiditis: a tender swelling behind the ear which pushes the ear forward

Supportive care

- ►

If the child has a high fever (≥ 39 °C or ≥ 102.2 °F) that is causing distress or discomfort, give paracetamol.

Monitoring

The child should be checked by a nurse at least every 6 h and by a doctor at least once a day. If the child responds poorly to treatment, such as decreasing level of consciousness, seizure or localizing neurological signs, consider the possibility of meningitis or brain abscess (see section 6.3).

6.7.2. Acute otitis media

Diagnosis

This is based on a history of ear pain or pus draining from the ear (for < 2 weeks). On examination, confirm acute otitis media by otoscopy. The ear-drum will be red, inflamed, bulging and opaque, or perforated with discharge.

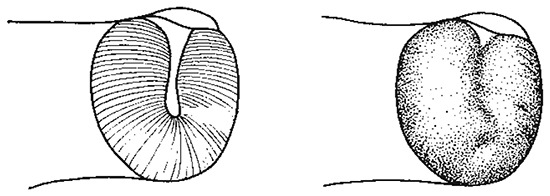

Acute otitis media: bulging, red ear-drum (on right) and normal ear-drum (on left)

Treatment

Treat the child as an outpatient.

- ►

Give oral antibiotics in one of the following regimens:-

- –

First choice: oral amoxicillin at 40 mg/kg twice a day for at least 5 days

- –

Alternatively, when the pathogens causing acute otitis media are known to be sensitive to co-trimoxazole, give co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim 4 mg/kg and sulfamethoxozole 20 mg/kg) twice a day for at least 5 days.

- ►

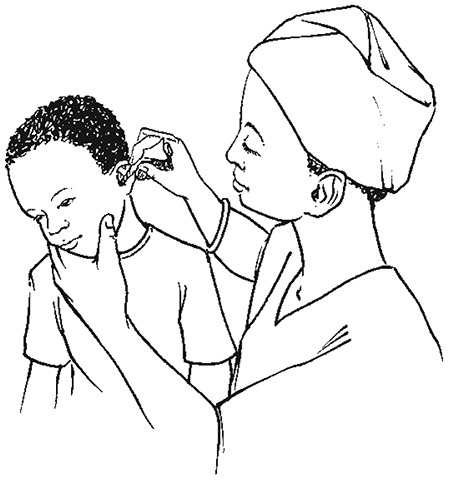

If pus is draining from the ear, show the mother how to dry the ear by wicking. Advise the mother to wick the ear three times daily until there is no more pus.

- ►

Tell the mother not to place anything in the ear between wicking treatments. Do not allow the child to go swimming or get water in the ear.

- ►

If the child has ear pain or high fever (≥ 39 °C or ≥ 102.2 °F) that is causing distress, give paracetamol.

Wicking the child's ear dry in otitis media

Follow-up

Ask the mother to return after 5 days.

- If ear pain or discharge persists, treat for 5 more days with the same antibiotic and continue wicking the ear. Follow up in 5 days.

6.7.3. Chronic otitis media

If pus has been draining from the ear for ≥ 2 weeks, the child has a chronic ear infection.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis is based on a history of pus draining from the ear for > 2 weeks. On examination, confirm chronic otitis media (where possible) by otoscopy.

Treatment

Treat the child as an outpatient.

- ►

Keep the ear dry by wicking (see above).

- ►

Instill topical antibiotic drops containing quinolones with or without steroids (such as ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin) twice a day for 2 weeks. Drops containing quinolones are more effective than other antibiotic drops. Topical antiseptics are not effective in the treatment of chronic otitis media in children.

Follow-up

Ask the mother to return after 5 days.

If the ear discharge persists:

- Check that the mother is continuing to wick the ear. Do not give repeated courses of oral antibiotics for a draining ear.

- Consider other causative organisms like Pseudomonas or possible tuberculous infection. Encourage the mother to continue to wick the ear dry and give parenteral antibiotics that are effective against Pseudomonas (such as gentamicin, azlocillin and ceftazidine) or TB treatment after confirmation.

6.8. Urinary tract infection

Urinary tract infection is common in boys during young infancy because of posterior urethral valves; it occurs in older female infants and children. When bacterial culture is not possible, the diagnosis is based on clinical signs and microscopy for bacteria and white cells on a good-quality sample of urine (see below).

Diagnosis

In young children, urinary tract infection often presents as nonspecific signs. Consider a diagnosis of urinary tract infection in all infants and children with:

- fever of ≥ 38 °C for at least 24 h without obvious cause

- vomiting or poor feeding

- irritability, lethargy, failure to thrive, abdominal pain, jaundice (neonates)

- specific symptoms such as increased frequency, pain on passing urine, abdominal (loin) pain or increased frequency of passing urine, especially in older children

Half of all infants with a urinary tract infection have fever and no other symptom or sign; so the only way to make the diagnosis is to check the urine.

Investigations

- Examine a clean, fresh, un-centrifuged specimen of urine under a microscope. Cases of urinary tract infection usually have more than five white cells per high-power field, or a dipstick shows a positive result for leukocytes. If microscopy shows no bacteriuria and no pyuria or the dipstick tests are negative, rule out urinary tract infection.

- If possible, obtain a ‘clean’ urine sample for culture. In sick infants, a specimen taken with an in–out urinary catheter or supra-pubic bladder aspiration may be required).

Treatment

- ►

Treat the child as an outpatient. Give an oral antibiotic for 7–10 days, except:

- –

when there is high fever and systemic upset (such as vomiting or inability to drink or breastfeed)

- –

when there are signs of pyelonephritis (loin pain or tenderness)

- –

for infants

- ►

Give oral co-trimoxazole (10 mg/kg trimethoprim and 40 mg/kg sulfamethoxazole every 12 h) for 5 days. Alternatives include ampicillin, amoxicillin and cefalexin, depending on local sensitivity patterns of E. coli and other Gram-negative bacilli that cause urinary tract infection and on the availability of antibiotics.

- ►

If there is a poor response to the first-line antibiotic or the child's condition deteriorates or with complications, give gentamicin (7.5 mg/kg IM or IV once daily) plus ampicillin (50 mg/kg IM or IV every 6 h) or parenteral cephalosporin. Consider complications such as pyelonephritis (tenderness in the costo-vertebral angle and high fever) or septicaemia.

- ►

Treat young infants aged < 2 months with gentamicin at 7.5 mg/kg IM or IV once daily until the fever has subsided; then review, look for signs of systemic infection, and, if absent, continue with oral treatment, as described above.

Supportive care

- The child should be encouraged to drink or breastfeed regularly in order to maintain a good fluid intake, which will assist in clearing the infection and prevent dehydration.

- If the child has pain, treat with paracetamol; avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Follow-up

Investigate all episodes of urinary tract infection in all children with more than one episode in order to identify a possible anatomical cause. This may require referral to a larger hospital with facilities for appropriate ultrasound investigations.

6.9. Septic arthritis or osteomyelitis

Acute infection of the bone or joint is usually caused by spread of bacteria through the blood. However, some bone or joint infections result from an adjacent focus of infection or from a penetrating injury. Occasionally, several bones or joints are involved.

Diagnosis

In acute cases of bone or joint infection, the child looks ill, is febrile and usually refuses to move the affected limb or joint or bear weight on the affected leg. In acute osteomyelitis, there is usually swelling over the bone and tenderness. Septic arthritis typically presents as a hot, swollen, tender joint or joints with reduced range of movement.

These infections sometimes present as chronic illness; the child appears less ill, with less marked local signs, and may not have a fever. Consider tuberculous osteomyelitis when the illness is chronic, there are discharging sinuses or the child has other signs of TB.

Laboratory investigations

X-rays are not helpful in diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. If septic arthritis is strongly suspected, introduce a sterile needle under strictly aseptic conditions into the affected joint and aspirate it. The fluid may be cloudy. If there is pus in the joint, use a wide-bore needle (after local anaesthesia with 1% lignocaine) to obtain a sample and remove as much pus as possible. Examine the fluid for white blood cells and carry out culture, if possible.

Staphylococcus aureus is the usual cause in children aged > 3 years. In younger children, the commonest causes are H. influenzae type b, Streptococcus pneumoniae or S. pyogenes group A. Salmonella is a common cause in young children in malarious areas and with sickle-cell disease.

Treatment

The choice of antibiotic is based on the organism involved, modified by the results of Gram staining and culture. If culture is possible, treat according to the causative organism and the results of antibiotic sensitivity tests. Otherwise:

- ►

Treat with IM or IV cloxacillin or flucloxacillin (50 mg/kg every 6 h) for children aged > 3 years. If this is not available, give chloramphenicol.

- ►

Clindamycin or second- or third-generation cephalosporins may be given.

- ►

Once the child's temperature returns to normal, change to equivalent oral treatment with the same antibiotics, and continue for a total of 3 weeks for septic arthritis and 5 weeks for osteomyelitis.

- ►

In cases of septic arthritis, remove the pus by aspirating the joint. If swelling recurs repeatedly after aspiration, or if the infection responds poorly to 3 weeks of antibiotic treatment, exploration, drainage of pus and excision of any dead bone should be done by a surgeon. In the case of septic arthritis, open drainage may be required. The duration of antibiotic treatment should be extended in these circumstances to 6 weeks.

- ►

Tuberculous osteomyelitis is suggested by a history of slow onset of swelling and a chronic course, which does not respond well to the above treatment. Treat according to national TB control programme guidelines. Surgical treatment is almost never needed because the abscesses will subside with anti-TB treatment.

Supportive care

The affected limb or joint should be rested. If it is the leg, the child should not be allowed to bear weight on it until pain-free. Treat pain or high fever (if it is causing discomfort to the child) with paracetamol.

6.10. Dengue

Dengue is caused by an arbovirus transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. It is highly seasonal in many countries in Asia and South America and increasingly in Africa. The illness usually starts with acute onset of fever, retro-orbital pain and continuously high temperatures for 2–7 days. Most children recover, but a small proportion develop severe disease. During the recovery period, a macular or confluent blanching rash is often noted.

Diagnosis

Suspect dengue fever in an area of risk for dengue if the child has fever lasting > 2 days.

- Headache, pain behind the eyes, joint and muscle pain, abdominal pain, vomiting and/or a rash may occur but are not always present. It can be difficult to distinguish dengue from other common childhood infections.

Treatment

Most children can be managed at home, provided the parents have good access to a hospital.

- ►

Counsel the parents to bring the child back for daily follow-up and to return immediately if any of the following occur: severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, cold, clammy extremities, lethargy or restlessness, bleeding, e.g. black stools or coffee-ground vomit.

- ►

Encourage oral fluid intake with clean water or ORS solution to replace losses during fever and vomiting.

- ►

Give paracetamol for high fever if the child is uncomfortable. Do not give aspirin or NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, as these drugs may aggravate bleeding.

- ►

Follow-up the child daily until the temperature is normal. Check the EVF daily if possible. Check for signs of severe disease.

- ►

Admit any child with signs of severe disease (mucosal or severe skin bleeding, shock, altered mental status, convulsions or jaundice) or with a rapid or marked rise in EVF.

6.10.1. Severe dengue

Severe dengue is defined by one or more of the following:

- plasma leakage that may lead to shock (dengue shock) and fluid accumulation

- severe bleeding

- severe organ impairment.

Plasma leakage, sometimes sufficient to cause shock, is the most important complication of dengue infection in children. The patient is considered to have shock if the pulse pressure (i.e. the difference between the systolic and diastolic pressures) is ≤ 20 mm Hg or he or she has signs of poor capillary perfusion (cold extremities, delayed capillary refill or rapid weak pulse rate). Systolic hypotension is usually a late sign. Shock often occurs on day 4–5 of illness. Early presentation with shock (day 2 or 3 of illness), very narrow pulse pressure (≤ 10 mm Hg) or undetectable pulse and blood pressure suggest very severe disease.

Other complications of dengue include skin or mucosal bleeding and, occasionally, hepatitis and encephalopathy. Most deaths occur in children in profound shock, particularly if the situation is complicated by fluid overload (see below).

Diagnosis

Suspect severe dengue in an area of risk for dengue if the child has fever lasting > 2 days, and any of the following features:

- evidence of plasma leakage

- –

high or progressively rising EVF

- –

pleural effusions or ascites

- circulatory compromise or shock

- –

cold, clammy extremities

- –

prolonged capillary refill time (> 3 s)

- –

weak pulse (fast pulse may be absent even with significant volume depletion)

- –

narrow pulse pressure (see above)

- spontaneous bleeding

- –

from the nose or gums

- –

black stools or coffee-ground vomit

- –

skin bruising or extensive petaechiae

- altered level of consciousness

- –

lethargy or restlessness

- –

coma

- –

convulsions

- severe gastrointestinal involvement

- –

persistent vomiting

- –

increasing abdominal pain with tenderness in the right upper quadrant

- –

jaundice

Treatment

- ►

Admit all patients with severe dengue to a hospital with facilities for urgent IV fluid treatment and blood pressure and EVF monitoring.

Fluid management: patients without shock (pulse pressure > 20 mm Hg)

- ►

Give IV fluids for repeated vomiting or a high or rapidly rising EVF.

- ►

Give only isotonic solutions such as normal saline and Ringer's lactate (Hartmann's solution) or 5% glucose in Ringer's lactate.

- ►

Start with 6 ml/kg per h for 2 h, and then reduce to 2–3 ml/kg per h as soon as possible, depending on the clinical response.

Give the minimum volume required to maintain good perfusion and urine output. IV fluids are usually needed only for 24–48 h, as the capillary leak resolves spontaneously after that time.

Fluid management: patients in shock (pulse pressure ≤ 20 mm Hg)

- ►

Treat as an emergency. Give 10–20 ml/kg of an isotonic crystalloid solution such as Ringer's lactate (Hartmann's solution) or normal saline over 1 h.

- –

If the child responds (capillary refill and peripheral perfusion start to improve, pulse pressure widens), reduce to 10 ml/kg for 1 h and then gradually to 2–3 ml/kg per h over the next 6–8 h.

- –

If the child does not respond (continuing signs of shock), give a further 20 ml/kg of the crystalloid over 1 h, or consider giving 10 ml/kg of a colloid solution such as 6% dextran 70 or 6% hetastarch (molecular mass, 200 000) over 1 h. Revert to the crystalloid schedule described above as soon as possible.

- ►

Further small boluses of extra fluid (5–10 ml/kg over 1 h) may be required during the next 24–48 h.

- ►

Decide on fluid treatment on the basis of clinical response, i.e. review vital signs hourly, EVF and monitor urine output closely. Changes in the EVF can be a useful guide to treatment but must be interpreted with the clinical response. For example, a rising EVF with unstable vital signs (particularly narrowing of the pulse pressure) indicates the need for a further bolus of fluid, but extra fluid is not needed if the vital signs are stable, even if the EVF is very high (50–55%). In these circumstances, continue to monitor frequently. The EVF is likely to start falling within the next 24 h as the reabsorptive phase of the disease begins.

- ►

In most cases, IV fluids can be stopped after 36–48 h. Remember that too much fluid can result into death due to fluid overload.

Treatment of haemorrhagic complications

- ■

Mucosal bleeding may occur in any patient with dengue but is usually minor. It is due mainly to the low platelet count, and this usually improves rapidly during the second week of illness.

- ■

If major bleeding occurs, it is usually in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in patients with very severe or prolonged shock. Internal bleeding may not become apparent for many hours, until the first black stool is passed. Consider this possibility in children with shock who fail to improve clinically with fluid treatment, particularly if they become very pale, if their EVF is falling or if the abdomen is distended and tender.

- ►

In children with profound thrombocytopenia (< 20 000 platelets/mm3), ensure strict bed rest and protect from trauma to reduce the risk of bleeding. Do not give IM injections.

- ►

Monitor the clinical condition, EVF and, when possible, platelet count.

- ►

Transfusion is rarely necessary. When indicated, it should be given with extreme care because of the problem of fluid overload. If major bleeding is suspected, give 5–10 ml/kg fresh whole blood or 10 ml/kg packed cells slowly over 2–4 h, and observe the clinical response. Consider repeating if there is a good clinical response and significant bleeding is confirmed.

- ►

Platelet concentrates (if available) should be given only if there is severe bleeding. They are of no value for the treatment of thrombocytopenia without bleeding and may be harmful.

Treatment of fluid overload

Fluid overload is an important complication of treatment for shock. It can develop due to:

- –

excess or too rapid IV fluids

- –

incorrect use of hypotonic rather than isotonic crystalloid solutions

- –

continuation of IV fluids for too long (once plasma leakage has resolved)

- –

use of large volumes of IV fluid in children with severe capillary leakage

- Early signs:

- –

fast breathing

- –

chest indrawing

- –

large pleural effusions

- –

ascites

- –

peri-orbital or soft tissue oedema

- Late signs:

- –

pulmonary oedema

- –

cyanosis

- –

irreversible shock (often a combination of ongoing hypovolaemia and cardiac failure)

The management of fluid overload varies depending on whether the child is in or out of shock:

- Children who remain in shock and show signs of severe fluid overload are extremely difficult to manage and have a high mortality.

- ►

Repeated small boluses of a colloid solution may help, with inotropic agents to support the circulation (see standard textbooks of paediatrics).

- ►

Avoid diuretics, as they will cause further intravascular fluid depletion.

- ►

Aspiration of large pleural effusions or ascites may be needed to relieve respiratory symptoms, but there is the risk of bleeding during the procedure.

- ►

If available, consider early positive pressure ventilation before pulmonary oedema develops.

- If shock has resolved but the child has fast or difficult breathing and large effusions, give oral or IV furosemide at 1 mg/kg once or twice a day for 24 h and oxygen therapy.