NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002-.

PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet].

Show detailsThis PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians who care for cancer patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

General Information About Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

Cancer in children and adolescents is rare, although the overall incidence of childhood cancer, including ALL, has been slowly increasing since 1975.[1] Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved in children and adolescents with cancer.[1-3] Between 1975 and 2010, childhood cancer mortality decreased by more than 50%.[1-3] For ALL, the 5-year survival rate has increased over the same time from 60% to approximately 90% for children younger than 15 years and from 28% to more than 75% for adolescents aged 15 to 19 years.[4] Childhood and adolescent cancer survivors require close monitoring because cancer therapy side effects may persist or develop months or years after treatment. (Refer to the PDQ summary on Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer for specific information about the incidence, type, and monitoring of late effects in childhood and adolescent cancer survivors.)

Incidence

ALL is the most common cancer diagnosed in children and represents approximately 25% of cancer diagnoses among children younger than 15 years.[2,3] In the United States, ALL occurs at an annual rate of approximately 41 cases per 1 million people aged 0 to 14 years and approximately 17 cases per 1 million people aged 15 to 19 years.[4] There are approximately 3,100 children and adolescents younger than 20 years diagnosed with ALL each year in the United States.[5] Since 1975, there has been a gradual increase in the incidence of ALL.[4,6]

A sharp peak in ALL incidence is observed among children aged 2 to 3 years (>90 cases per 1 million per year), with rates decreasing to fewer than 30 cases per 1 million by age 8 years.[2,3] The incidence of ALL among children aged 2 to 3 years is approximately fourfold greater than that for infants and is likewise fourfold to fivefold greater than that for children aged 10 years and older.[2,3]

The incidence of ALL appears to be highest in Hispanic children (43 cases per 1 million).[2,3,7,8] The incidence is substantially higher in White children than in Black children, with a nearly threefold higher incidence of ALL from age 2 to 3 years in White children than in Black children.[2,3,7]

Anatomy

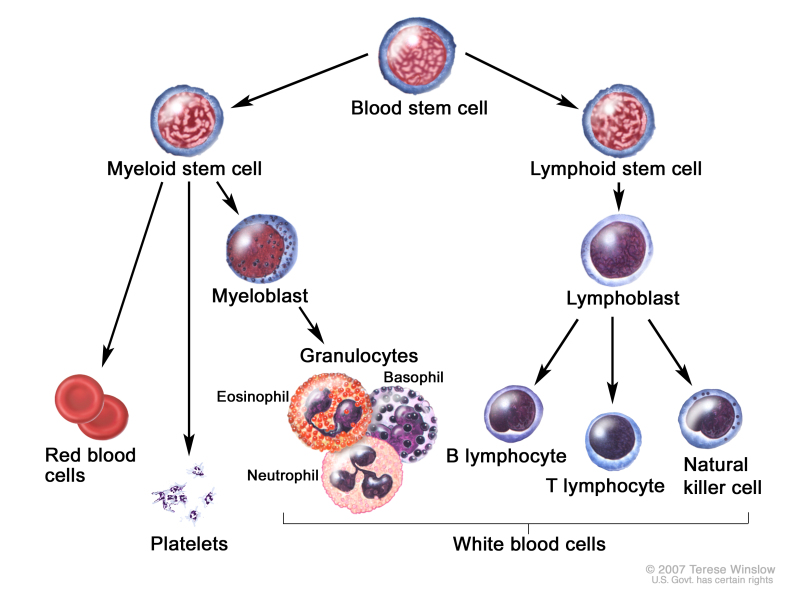

Childhood ALL originates in the T and B lymphoblasts in the bone marrow (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1. Blood cell development. Different blood and immune cell lineages, including T and B lymphocytes, differentiate from a common blood stem cell.

Marrow involvement of acute leukemia as seen by light microscopy is defined as follows:

- M1: Fewer than 5% blast cells.

- M2: 5% to 25% blast cells.

- M3: Greater than 25% blast cells.

Almost all patients with ALL present with an M3 marrow.

Morphology

In the past, ALL lymphoblasts were classified using the French-American-British (FAB) criteria as having L1 morphology, L2 morphology, or L3 morphology.[9] However, because of the lack of independent prognostic significance and the subjective nature of this classification system, it is no longer used.

Most cases of ALL that show L3 morphology express surface immunoglobulin (Ig) and have a MYC gene translocation identical to those seen in Burkitt lymphoma (i.e., t(8;14)(q24;q32), t(2;8)) that join MYC to one of the Ig genes. Patients with this specific rare form of leukemia (mature B-cell or Burkitt leukemia) should be treated according to protocols for Burkitt lymphoma. (Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment for more information about the treatment of mature B-cell lymphoma/leukemia and Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia.) Rarely, blasts with L1/L2 (not L3) morphology will express surface Ig.[10] These patients should be treated in the same way as are patients with B-ALL.[10]

Risk Factors for Developing ALL

Few factors associated with an increased risk of ALL have been identified. The primary accepted risk factors for ALL and associated genes (when relevant) include the following:

- Prenatal exposure to x-rays.

- Postnatal exposure to high doses of radiation (e.g., therapeutic radiation as previously used for conditions such as tinea capitis and thymus enlargement).

- Previous treatment with chemotherapy.

- Genetic conditions that include the following:

- -

Down syndrome. (Refer to the Down syndrome section of this summary for more information.)

- -

Neurofibromatosis (NF1).[11]

- -

Bloom syndrome (BLM).[12]

- -

Fanconi anemia (multiple genes; ALL is observed much less frequently than acute myeloid leukemia [AML]).[13]

- -

Ataxia telangiectasia (ATM).[14]

- -

- -

Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (biallelic mutation of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2).[18,19]

- Low- and high-penetrance inherited genetic variants.[20] (Refer to the Low- and high-penetrance inherited genetic variants section of this summary for more information.)

- Carriers of a constitutional Robertsonian translocation that involves chromosomes 15 and 21 are specifically and highly predisposed to developing intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 (iAMP21) ALL.[21]

Down syndrome

Children with Down syndrome have an increased risk of developing both ALL and AML,[22,23] with a cumulative risk of developing leukemia of approximately 2.1% by age 5 years and 2.7% by age 30 years.[22,23]

Approximately one-half to two-thirds of cases of acute leukemia in children with Down syndrome are ALL, and about 2% to 3% of childhood ALL cases occur in children with Down syndrome (noting a prevalence of Down syndrome during childhood of approximately 0.1%).[24-27] ALL in children with Down syndrome has an age distribution similar to that of ALL in children without Down syndrome, with a median age of 3 to 4 years.[24,25] In contrast, the vast majority of cases of AML in children with Down syndrome occur before the age of 4 years (median age, 1 year).[28]

Patients with ALL and Down syndrome have a lower incidence of both favorable (t(12;21)(p13;q22)/ETV6-RUNX1 [TEL-AML1] and hyperdiploidy [51–65 chromosomes]) and unfavorable (t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) or t(4;11)(q21;q23) and hypodiploidy [<44 chromosomes]) cytogenetic findings and a near absence of T-cell phenotype.[24-26,28,29]

Approximately 50% to 60% of cases of ALL in children with Down syndrome have genomic alterations affecting CRLF2 that generally result in overexpression of the protein produced by this gene, which dimerizes with the interleukin-7 receptor alpha to form the receptor for the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin.[30-32] CRLF2 genomic alterations are observed at a much lower frequency (<10%) in children with B-ALL who do not have Down syndrome.[32-34] Based on the relatively small number of published series, it does not appear that genomic CRLF2 aberrations in patients with Down syndrome and ALL have prognostic relevance, but more studies are needed to address this issue.[29,31]

Approximately 20% of ALL cases arising in children with Down syndrome have somatically acquired JAK2 mutations,[30,31,35-37] a finding that is uncommon among younger children with ALL but that is observed in a subset of primarily older children and adolescents with high-risk B-ALL.[38] Almost all Down syndrome ALL cases with JAK2 mutations also have CRLF2 genomic alterations.[30-32] Preliminary evidence suggests no correlation between JAK2 mutation status and 5-year event-free survival (EFS) in children with Down syndrome and ALL,[31,36] but more study is needed to address this issue.

A genome-wide association study found that four susceptibility loci associated with B-ALL in the non-Down syndrome population (IKZF1, CDKN2A, ARID5B, and GATA3) were also associated with susceptibility to ALL in children with Down syndrome.[39] CDKN2A risk allele penetrance appeared to be higher for children with Down syndrome.

IKZF1 gene deletions, observed in up to 35% of patients with Down syndrome and ALL, have been associated with a significantly worse outcome in this group of patients.[31,40]

Low- and high-penetrance inherited genetic variants

Genetic predisposition to ALL can be divided into several broad categories, as follows:

- Association with genetic syndromes. Increased risk can be associated with the genetic syndromes listed above in which ALL is observed, although it is not the primary manifestation of the condition.

- Common alleles. Another category for genetic predisposition includes common alleles with relatively small effect sizes that are identified by genome-wide association studies. Genome-wide association studies have identified a number of germline (inherited) genetic polymorphisms that are associated with the development of childhood ALL.[20] For example, the risk alleles of ARID5B are associated with the development of hyperdiploid (51–65 chromosomes) B-ALL. ARID5B is a gene that encodes a transcriptional factor important in embryonic development, cell type–specific gene expression, and cell growth regulation.[41,42] Other genes with polymorphisms associated with increased risk of ALL include GATA3,[43] IKZF1,[41,42,44] CDKN2A,[45] CDKN2B,[44,45] CEBPE,[41] PIP4K2A,[43,46] and TP63.[47]A genome-wide association study found that four susceptibility loci associated with B-ALL in the non-Down syndrome population (IKZF1, CDKN2A, ARID5B, and GATA3) were also associated with susceptibility to ALL in children with Down syndrome.[39] CDKN2A risk allele penetrance appeared to be higher for children with Down syndrome.Genetic risk factors for T-ALL share some overlap with the genetic risk factors for B-ALL, but unique risk factors also exist. A genome-wide association study identified a risk allele near USP7 that was associated with an increased risk of developing T-ALL (odds ratio, 1.44) but not B-ALL. The risk allele was shown to be associated with reduced USP7 transcription, which is consistent with the finding that somatic loss-of-function mutations in USP7 are observed in patients with T-ALL. USP7 germline and somatic mutations are generally mutually exclusive and are most commonly observed in T-ALL patients with TAL1 alterations.[48]Genetic risk factors that have similar impact for developing both B-ALL and T-ALL include CDKN2A/B and 8q24.21 (cis distal enhancer region variants for MYC).[48]

- Rare germline variants with high penetrance. Germline variants that cause pathogenic changes in genes associated with ALL and that are observed in kindreds with familial ALL (i.e., large effect sizes) comprise another category of genetic predisposition to ALL.

- ETV6. Several germline ETV6 variants that lead to loss of ETV6 function have been identified in kindreds affected by both thrombocytopenia and ALL.[51-55] Sequencing of ETV6 in remission (i.e., germline) specimens identified variants that were potentially related to ALL in approximately 1% of children with ALL that were evaluated.[51] Most of the germline mutations (approximately 75%) were shown to be deleterious for ETV6 function, and 70% of cases with a deleterious germline ETV6 variant had a hyperdiploid karyotype. The remaining cases with a deleterious mutation had diploid ALL, with a transcriptional profile similar to that of cases with ETV6-RUNX1 fusion–positive ALL.[55]

- TP53. Pathogenic germline TP53 variants are associated with an increased risk of ALL.[56] A study of 3,801 children with ALL observed that 26 patients (0.7%) had a pathogenic TP53 germline variant, with an associated odds ratio of 5.2 for ALL development.[56] Compared with ALL in children with TP53 wild-type status or TP53 variants of unknown significance, ALL in children with pathogenic germline TP53 variants was associated with older age at diagnosis (15.5 years vs. 7.3 years), hypodiploidy (65% vs. 1%), inferior EFS and overall survival, and a higher risk of second cancers.

- IKZF1. Germline IKZF1 variants were identified in a kindred with familial ALL and in 43 of 4,963 (0.9%) children with sporadic ALL. Most (22 of 28) IKZF1 variants were shown to adversely affect IKZF1 gene function.[57] Germline variants in IKZF1 have been identified in hereditary hypogammaglobulinemia, and in one series, 2 of 29 affected patients developed B-ALL during childhood.[58]

Prenatal origin of childhood ALL

Development of ALL is a multistep process in most cases, with more than one genomic alteration required for frank leukemia to develop. In at least some cases of childhood ALL, the initial genomic alteration appears to occur in utero. Evidence to support this comes from the observation that the immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor antigen rearrangements that are unique to each patient’s leukemia cells can be detected in blood samples obtained at birth.[59,60] Similarly, in ALL characterized by specific chromosomal abnormalities, some patients have blood cells that carry at least one leukemic genomic abnormality at the time of birth, with additional cooperative genomic changes acquired postnatally.[59-61] Genomic studies of identical twins with concordant leukemia further support the prenatal origin of some leukemias.[59,62]

Evidence also exists that some children who never develop ALL are born with rare blood cells carrying a genomic alteration associated with ALL. Initial studies focused on the ETV6-RUNX1 translocation and used reverse transcriptase (RT)–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to identify RNA transcripts indicating the presence of the gene fusion. For example, in one study, 1% of neonatal blood spots (Guthrie cards) tested positive for the ETV6-RUNX1 translocation.[63] While subsequent reports generally confirmed the presence of the ETV6-RUNX1 translocation at birth in some children, rates and extent of positivity varied widely.

To more definitively address this question, a highly sensitive and specific DNA-based approach (genomic inverse PCR for exploration of ligated breakpoints [GIPFEL]) was applied to DNA from 1,000 cord blood specimens and found that 5% of specimens had the ETV6-RUNX1 translocation.[64] When the same method was applied to 340 cord blood specimens to detect the TCF3-PBX1 fusion, two cord specimens (0.6%) were positive for its presence.[65] For both ETV6-RUNX1 and TCF3-PBX1, the percentage of cord blood specimens positive for one of the translocations far exceeds the percentage of children who will develop either type of ALL (<0.01%).

Clinical Presentation

The typical and atypical symptoms and clinical findings of childhood ALL have been published.[66-68]

Overall Prognosis

Among children with ALL, approximately 98% attain remission. Approximately 85% of patients aged 1 to 18 years with newly diagnosed ALL treated on current regimens are expected to be long-term event-free survivors, with over 90% surviving at 5 years.[71-74] Cytogenetic and genomic findings combined with minimal residual disease (MRD) results can define subsets of ALL with EFS rates exceeding 95% and, conversely, subsets with EFS rates of 50% or lower (refer to the Cytogenetics/Genomics of Childhood ALL and Prognostic Factors Affecting Risk-Based Treatment sections of this summary for more information).

Despite the treatment advances in childhood ALL, numerous important biologic and therapeutic questions remain to be answered before the goal of curing every child with ALL with the least associated toxicity can be achieved. The systematic investigation of these issues requires large clinical trials, and the opportunity to participate in these trials is offered to most patients and families.

Clinical trials for children and adolescents with ALL are generally designed to compare therapy that is currently accepted as standard with investigational regimens that seek to improve cure rates and/or decrease toxicity. In certain trials in which the cure rate for the patient group is very high, therapy reduction questions may be asked. Much of the progress made in identifying curative therapies for childhood ALL and other childhood cancers has been achieved through investigator-driven discovery and tested in carefully randomized, controlled, multi-institutional clinical trials. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014. [PMC free article: PMC4136455] [PubMed: 24853691]

- Childhood cancer. In: Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., eds.: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010. National Cancer Institute, 2013, Section 28. Also available online. Last accessed June 03, 2021.

- Childhood cancer by the ICCC. In: Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., eds.: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010. National Cancer Institute, 2013, Section 29. Also available online. Last accessed June 03, 2021.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M: SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975-2013. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute, 2015. Available online. Last accessed June 04, 2021.

- Special section: cancer in children and adolescents. In: American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2014. American Cancer Society, 2014, pp 25-42. Available online. Last accessed June 04, 2021.

- Shah A, Coleman MP: Increasing incidence of childhood leukaemia: a controversy re-examined. Br J Cancer 97 (7): 1009-12, 2007. [PMC free article: PMC2360402] [PubMed: 17712312]

- Smith MA, Ries LA, Gurney JG, et al.: Leukemia. In: Ries LA, Smith MA, Gurney JG, et al., eds.: Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, 1999. NIH Pub.No. 99-4649, pp 17-34. Also available online. Last accessed June 04, 2021.

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Cockburn M, Metayer C, et al.: Rising rates of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Hispanic children: trends in incidence from 1992 to 2011. Blood 125 (19): 3033-4, 2015. [PMC free article: PMC4424421] [PubMed: 25953979]

- Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, et al.: The morphological classification of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: concordance among observers and clinical correlations. Br J Haematol 47 (4): 553-61, 1981. [PubMed: 6938236]

- Koehler M, Behm FG, Shuster J, et al.: Transitional pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia of childhood is associated with favorable prognostic clinical features and an excellent outcome: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Leukemia 7 (12): 2064-8, 1993. [PubMed: 8255107]

- Stiller CA, Chessells JM, Fitchett M: Neurofibromatosis and childhood leukaemia/lymphoma: a population-based UKCCSG study. Br J Cancer 70 (5): 969-72, 1994. [PMC free article: PMC2033537] [PubMed: 7947106]

- Passarge E: Bloom's syndrome: the German experience. Ann Genet 34 (3-4): 179-97, 1991. [PubMed: 1809225]

- Alter BP: Cancer in Fanconi anemia, 1927-2001. Cancer 97 (2): 425-40, 2003. [PubMed: 12518367]

- Taylor AM, Metcalfe JA, Thick J, et al.: Leukemia and lymphoma in ataxia telangiectasia. Blood 87 (2): 423-38, 1996. [PubMed: 8555463]

- Holmfeldt L, Wei L, Diaz-Flores E, et al.: The genomic landscape of hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 45 (3): 242-52, 2013. [PMC free article: PMC3919793] [PubMed: 23334668]

- Powell BC, Jiang L, Muzny DM, et al.: Identification of TP53 as an acute lymphocytic leukemia susceptibility gene through exome sequencing. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60 (6): E1-3, 2013. [PMC free article: PMC3926299] [PubMed: 23255406]

- Hof J, Krentz S, van Schewick C, et al.: Mutations and deletions of the TP53 gene predict nonresponse to treatment and poor outcome in first relapse of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 29 (23): 3185-93, 2011. [PubMed: 21747090]

- Ilencikova D, Sejnova D, Jindrova J, et al.: High-grade brain tumors in siblings with biallelic MSH6 mutations. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57 (6): 1067-70, 2011. [PubMed: 21674763]

- Ripperger T, Schlegelberger B: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma in the context of constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome. Eur J Med Genet 59 (3): 133-42, 2016. [PubMed: 26743104]

- Moriyama T, Relling MV, Yang JJ: Inherited genetic variation in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 125 (26): 3988-95, 2015. [PMC free article: PMC4481591] [PubMed: 25999454]

- Li Y, Schwab C, Ryan SL, et al.: Constitutional and somatic rearrangement of chromosome 21 in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 508 (7494): 98-102, 2014. [PMC free article: PMC3976272] [PubMed: 24670643]

- Hasle H: Pattern of malignant disorders in individuals with Down's syndrome. Lancet Oncol 2 (7): 429-36, 2001. [PubMed: 11905737]

- Whitlock JA: Down syndrome and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 135 (5): 595-602, 2006. [PubMed: 17054672]

- Zeller B, Gustafsson G, Forestier E, et al.: Acute leukaemia in children with Down syndrome: a population-based Nordic study. Br J Haematol 128 (6): 797-804, 2005. [PubMed: 15755283]

- Arico M, Ziino O, Valsecchi MG, et al.: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Down syndrome: presenting features and treatment outcome in the experience of the Italian Association of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology (AIEOP). Cancer 113 (3): 515-21, 2008. [PubMed: 18521927]

- Maloney KW, Carroll WL, Carroll AJ, et al.: Down syndrome childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia has a unique spectrum of sentinel cytogenetic lesions that influences treatment outcome: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Blood 116 (7): 1045-50, 2010. [PMC free article: PMC2938126] [PubMed: 20442364]

- de Graaf G, Buckley F, Skotko BG: Estimation of the number of people with Down syndrome in the United States. Genet Med 19 (4): 439-447, 2017. [PubMed: 27608174]

- Chessells JM, Harrison G, Richards SM, et al.: Down's syndrome and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: clinical features and response to treatment. Arch Dis Child 85 (4): 321-5, 2001. [PMC free article: PMC1718934] [PubMed: 11567943]

- Buitenkamp TD, Izraeli S, Zimmermann M, et al.: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children with Down syndrome: a retrospective analysis from the Ponte di Legno study group. Blood 123 (1): 70-7, 2014. [PMC free article: PMC3879907] [PubMed: 24222333]

- Hertzberg L, Vendramini E, Ganmore I, et al.: Down syndrome acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a highly heterogeneous disease in which aberrant expression of CRLF2 is associated with mutated JAK2: a report from the International BFM Study Group. Blood 115 (5): 1006-17, 2010. [PubMed: 19965641]

- Buitenkamp TD, Pieters R, Gallimore NE, et al.: Outcome in children with Down's syndrome and acute lymphoblastic leukemia: role of IKZF1 deletions and CRLF2 aberrations. Leukemia 26 (10): 2204-11, 2012. [PubMed: 22441210]

- Mullighan CG, Collins-Underwood JR, Phillips LA, et al.: Rearrangement of CRLF2 in B-progenitor- and Down syndrome-associated acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 41 (11): 1243-6, 2009. [PMC free article: PMC2783810] [PubMed: 19838194]

- Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Chen IM, et al.: Rearrangement of CRLF2 is associated with mutation of JAK kinases, alteration of IKZF1, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, and a poor outcome in pediatric B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 115 (26): 5312-21, 2010. [PMC free article: PMC2902132] [PubMed: 20139093]

- Schwab CJ, Chilton L, Morrison H, et al.: Genes commonly deleted in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: association with cytogenetics and clinical features. Haematologica 98 (7): 1081-8, 2013. [PMC free article: PMC3696612] [PubMed: 23508010]

- Bercovich D, Ganmore I, Scott LM, et al.: Mutations of JAK2 in acute lymphoblastic leukaemias associated with Down's syndrome. Lancet 372 (9648): 1484-92, 2008. [PubMed: 18805579]

- Gaikwad A, Rye CL, Devidas M, et al.: Prevalence and clinical correlates of JAK2 mutations in Down syndrome acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 144 (6): 930-2, 2009. [PMC free article: PMC2724897] [PubMed: 19120350]

- Kearney L, Gonzalez De Castro D, Yeung J, et al.: Specific JAK2 mutation (JAK2R683) and multiple gene deletions in Down syndrome acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 113 (3): 646-8, 2009. [PubMed: 18927438]

- Mullighan CG, Zhang J, Harvey RC, et al.: JAK mutations in high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (23): 9414-8, 2009. [PMC free article: PMC2695045] [PubMed: 19470474]

- Brown AL, de Smith AJ, Gant VU, et al.: Inherited genetic susceptibility to acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Down syndrome. Blood 134 (15): 1227-1237, 2019. [PMC free article: PMC6788009] [PubMed: 31350265]

- Hanada I, Terui K, Ikeda F, et al.: Gene alterations involving the CRLF2-JAK pathway and recurrent gene deletions in Down syndrome-associated acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Japan. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 53 (11): 902-10, 2014. [PubMed: 25044358]

- Papaemmanuil E, Hosking FJ, Vijayakrishnan J, et al.: Loci on 7p12.2, 10q21.2 and 14q11.2 are associated with risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 41 (9): 1006-10, 2009. [PMC free article: PMC4915548] [PubMed: 19684604]

- Treviño LR, Yang W, French D, et al.: Germline genomic variants associated with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 41 (9): 1001-5, 2009. [PMC free article: PMC2762391] [PubMed: 19684603]

- Migliorini G, Fiege B, Hosking FJ, et al.: Variation at 10p12.2 and 10p14 influences risk of childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and phenotype. Blood 122 (19): 3298-307, 2013. [PubMed: 23996088]

- Hungate EA, Vora SR, Gamazon ER, et al.: A variant at 9p21.3 functionally implicates CDKN2B in paediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia aetiology. Nat Commun 7: 10635, 2016. [PMC free article: PMC4754340] [PubMed: 26868379]

- Sherborne AL, Hosking FJ, Prasad RB, et al.: Variation in CDKN2A at 9p21.3 influences childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia risk. Nat Genet 42 (6): 492-4, 2010. [PMC free article: PMC3434228] [PubMed: 20453839]

- Xu H, Yang W, Perez-Andreu V, et al.: Novel susceptibility variants at 10p12.31-12.2 for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in ethnically diverse populations. J Natl Cancer Inst 105 (10): 733-42, 2013. [PMC free article: PMC3691938] [PubMed: 23512250]

- Ellinghaus E, Stanulla M, Richter G, et al.: Identification of germline susceptibility loci in ETV6-RUNX1-rearranged childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 26 (5): 902-9, 2012. [PMC free article: PMC3356560] [PubMed: 22076464]

- Qian M, Zhao X, Devidas M, et al.: Genome-Wide Association Study of Susceptibility Loci for T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children. J Natl Cancer Inst 111 (12): 1350-1357, 2019. [PMC free article: PMC6910193] [PubMed: 30938820]

- Shah S, Schrader KA, Waanders E, et al.: A recurrent germline PAX5 mutation confers susceptibility to pre-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 45 (10): 1226-31, 2013. [PMC free article: PMC3919799] [PubMed: 24013638]

- Auer F, Rüschendorf F, Gombert M, et al.: Inherited susceptibility to pre B-ALL caused by germline transmission of PAX5 c.547G>A. Leukemia 28 (5): 1136-8, 2014. [PubMed: 24287434]

- Zhang MY, Churpek JE, Keel SB, et al.: Germline ETV6 mutations in familial thrombocytopenia and hematologic malignancy. Nat Genet 47 (2): 180-5, 2015. [PMC free article: PMC4540357] [PubMed: 25581430]

- Topka S, Vijai J, Walsh MF, et al.: Germline ETV6 Mutations Confer Susceptibility to Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Thrombocytopenia. PLoS Genet 11 (6): e1005262, 2015. [PMC free article: PMC4477877] [PubMed: 26102509]

- Noetzli L, Lo RW, Lee-Sherick AB, et al.: Germline mutations in ETV6 are associated with thrombocytopenia, red cell macrocytosis and predisposition to lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 47 (5): 535-8, 2015. [PMC free article: PMC4631613] [PubMed: 25807284]

- Rampersaud E, Ziegler DS, Iacobucci I, et al.: Germline deletion of ETV6 in familial acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv 3 (7): 1039-1046, 2019. [PMC free article: PMC6457220] [PubMed: 30940639]

- Nishii R, Baskin-Doerfler R, Yang W, et al.: Molecular basis of ETV6-mediated predisposition to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 137 (3): 364-373, 2021. [PMC free article: PMC7819760] [PubMed: 32693409]

- Qian M, Cao X, Devidas M, et al.: TP53 Germline Variations Influence the Predisposition and Prognosis of B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children. J Clin Oncol 36 (6): 591-599, 2018. [PMC free article: PMC5815403] [PubMed: 29300620]

- Churchman ML, Qian M, Te Kronnie G, et al.: Germline Genetic IKZF1 Variation and Predisposition to Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Cell 33 (5): 937-948.e8, 2018. [PMC free article: PMC5953820] [PubMed: 29681510]

- Kuehn HS, Boisson B, Cunningham-Rundles C, et al.: Loss of B Cells in Patients with Heterozygous Mutations in IKAROS. N Engl J Med 374 (11): 1032-1043, 2016. [PMC free article: PMC4836293] [PubMed: 26981933]

- Greaves MF, Wiemels J: Origins of chromosome translocations in childhood leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer 3 (9): 639-49, 2003. [PubMed: 12951583]

- Taub JW, Konrad MA, Ge Y, et al.: High frequency of leukemic clones in newborn screening blood samples of children with B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 99 (8): 2992-6, 2002. [PubMed: 11929791]

- Bateman CM, Colman SM, Chaplin T, et al.: Acquisition of genome-wide copy number alterations in monozygotic twins with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 115 (17): 3553-8, 2010. [PubMed: 20061556]

- Greaves MF, Maia AT, Wiemels JL, et al.: Leukemia in twins: lessons in natural history. Blood 102 (7): 2321-33, 2003. [PubMed: 12791663]

- Mori H, Colman SM, Xiao Z, et al.: Chromosome translocations and covert leukemic clones are generated during normal fetal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 (12): 8242-7, 2002. [PMC free article: PMC123052] [PubMed: 12048236]

- Schäfer D, Olsen M, Lähnemann D, et al.: Five percent of healthy newborns have an ETV6-RUNX1 fusion as revealed by DNA-based GIPFEL screening. Blood 131 (7): 821-826, 2018. [PMC free article: PMC5909885] [PubMed: 29311095]

- Hein D, Dreisig K, Metzler M, et al.: The preleukemic TCF3-PBX1 gene fusion can be generated in utero and is present in ≈0.6% of healthy newborns. Blood 134 (16): 1355-1358, 2019. [PMC free article: PMC7005361] [PubMed: 31434706]

- Rabin KR, Gramatges MM, Margolin JF, et al.: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, eds.: Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 7th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2015, pp 463-97.

- Chessells JM; haemostasis and thrombosis task force, British committee for standards in haematology: Pitfalls in the diagnosis of childhood leukaemia. Br J Haematol 114 (3): 506-11, 2001. [PubMed: 11552974]

- Onciu M: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 23 (4): 655-74, 2009. [PubMed: 19577163]

- Heerema-McKenney A, Cleary M, Arber D: Pathology and molecular diagnosis of leukemias and lymphomas. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, eds.: Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 7th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2015, pp 113-30.

- Cheng J, Klairmont MM, Choi JK: Peripheral blood flow cytometry for the diagnosis of pediatric acute leukemia: Highly reliable with rare exceptions. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66 (1): e27453, 2019. [PubMed: 30255571]

- Möricke A, Zimmermann M, Valsecchi MG, et al.: Dexamethasone vs prednisone in induction treatment of pediatric ALL: results of the randomized trial AIEOP-BFM ALL 2000. Blood 127 (17): 2101-12, 2016. [PubMed: 26888258]

- Vora A, Goulden N, Wade R, et al.: Treatment reduction for children and young adults with low-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia defined by minimal residual disease (UKALL 2003): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 14 (3): 199-209, 2013. [PubMed: 23395119]

- Place AE, Stevenson KE, Vrooman LM, et al.: Intravenous pegylated asparaginase versus intramuscular native Escherichia coli L-asparaginase in newly diagnosed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (DFCI 05-001): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 16 (16): 1677-90, 2015. [PubMed: 26549586]

- Pieters R, de Groot-Kruseman H, Van der Velden V, et al.: Successful Therapy Reduction and Intensification for Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Based on Minimal Residual Disease Monitoring: Study ALL10 From the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 34 (22): 2591-601, 2016. [PubMed: 27269950]

World Health Organization (WHO) Classification System for Childhood ALL

The 2016 revision to the WHO classification of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues lists the following entities for acute lymphoid leukemias:[1]

2016 WHO Classification of B-Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, not otherwise specified (NOS).

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with recurrent genetic abnormalities.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2); BCR-ABL1.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(v;11q23.3); KMT2A rearranged.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(12;21)(p13.2;q22.1); ETV6-RUNX1.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with hyperdiploidy.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with hypodiploidy.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(5;14)(q31.1;q32.3); IL3-IGH.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(1;19)(q23;p13.3); TCF3-PBX1.

- Provisional entity: B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, BCR-ABL1–like.

- Provisional entity: B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with iAMP21.

2016 WHO Classification of T-Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma

- Provisional entity: Early T-cell precursor lymphoblastic leukemia.

2016 WHO Classification of Acute Leukemias of Ambiguous Lineage

For acute leukemias of ambiguous lineage, the group of acute leukemias that have characteristics of both acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the WHO classification system is summarized in Table 1.[2,3] The criteria for lineage assignment for a diagnosis of mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) are provided in Table 2.[1]

Table 1. Acute Leukemias of Ambiguous Lineage According to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissuesa

| Condition | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acute undifferentiated leukemia | Acute leukemia that does not express any marker considered specific for either lymphoid or myeloid lineage |

| Mixed phenotype acute leukemia with t(9;22)(q34;q11.2); BCR-ABL1 (MPAL with BCR-ABL1) | Acute leukemia meeting the diagnostic criteria for mixed phenotype acute leukemia in which the blasts also have the (9;22) translocation or the BCR-ABL1 rearrangement |

| Mixed phenotype acute leukemia with t(v;11q23); KMT2A (MLL) rearranged (MPAL with KMT2A) | Acute leukemia meeting the diagnostic criteria for mixed phenotype acute leukemia in which the blasts also have a translocation involving the KMT2A gene |

| Mixed phenotype acute leukemia, B/myeloid, NOS (B/M MPAL) | Acute leukemia meeting the diagnostic criteria for assignment to both B and myeloid lineage, in which the blasts lack genetic abnormalities involving BCR-ABL1 or KMT2A |

| Mixed phenotype acute leukemia, T/myeloid, NOS (T/M MPAL) | Acute leukemia meeting the diagnostic criteria for assignment to both T and myeloid lineage, in which the blasts lack genetic abnormalities involving BCR-ABL1 or KMT2A |

| Mixed phenotype acute leukemia, B/myeloid, NOS—rare types | Acute leukemia meeting the diagnostic criteria for assignment to both B and T lineage |

| Other ambiguous lineage leukemias | Natural killer–cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma |

NOS = not otherwise specified.

aAdapted from Béné MC: Biphenotypic, bilineal, ambiguous or mixed lineage: strange leukemias! Haematologica 94 (7): 891-3, 2009.[2] Obtained from Haematologica/the Hematology Journal website http://www

.haematologica.org.

Table 2. Lineage Assignment Criteria for Mixed Phenotype Acute Leukemia According to the 2016 Revision to the World Health Organization Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemiaa

| Lineage | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Myeloid lineage | Myeloperoxidase (flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, or cytochemistry); or monocytic differentiation (at least two of the following: nonspecific esterase cytochemistry, CD11c, CD14, CD64, lysozyme) |

| T lineage | Strongb cytoplasmic CD3 (with antibodies to CD3 epsilon chain); or surface CD3 |

| B lineage | Strongb CD19 with at least one of the following strongly expressed: CD79a, cytoplasmic CD22, or CD10; or weak CD19 with at least two of the following strongly expressed: CD79a, cytoplasmic CD22, or CD10 |

aAdapted from Arber et al.[1]

bStrong defined as equal to or brighter than the normal B or T cells in the sample.

Leukemias of mixed phenotype may be seen in various presentations, including the following:

- Bilineal leukemias in which there are two distinct populations of cells, usually one lymphoid and one myeloid.

- Biphenotypic leukemias in which individual blast cells display features of both lymphoid and myeloid lineage.

Biphenotypic cases represent the majority of mixed phenotype leukemias.[4] Patients with B-myeloid biphenotypic leukemias lacking the TEL-AML1 fusion have lower rates of complete remission (CR) and significantly worse event-free survival (EFS) rates compared with patients with B-ALL.[4] Some studies suggest that patients with biphenotypic leukemia may fare better with a lymphoid, as opposed to a myeloid, treatment regimen.[5-8]; [9][Level of evidence: 3iiiA] A large retrospective study from the international Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM) group demonstrated that initial therapy with an ALL-type regimen was associated with a superior outcome compared with AML-type or combined ALL/AML regimens, particularly in cases with CD19 positivity or other lymphoid antigen expression. In this study, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in first CR was not beneficial, with the possible exception of cases with morphologic evidence of persistent marrow disease (≥5% blasts) after the first month of treatment.[8]

Key clinical and biological characteristics, as well as the prognostic significance for these entities, are discussed in the Cytogenetics/Genomics of Childhood ALL section of this summary.

References

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al.: The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 127 (20): 2391-405, 2016. [PubMed: 27069254]

- Béné MC: Biphenotypic, bilineal, ambiguous or mixed lineage: strange leukemias! Haematologica 94 (7): 891-3, 2009. [PMC free article: PMC2704297] [PubMed: 19570749]

- Borowitz MJ, Béné MC, Harris NL: Acute leukaemias of ambiguous lineage. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al., eds.: WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2008, pp 150-5.

- Gerr H, Zimmermann M, Schrappe M, et al.: Acute leukaemias of ambiguous lineage in children: characterization, prognosis and therapy recommendations. Br J Haematol 149 (1): 84-92, 2010. [PubMed: 20085575]

- Rubnitz JE, Onciu M, Pounds S, et al.: Acute mixed lineage leukemia in children: the experience of St Jude Children's Research Hospital. Blood 113 (21): 5083-9, 2009. [PMC free article: PMC2686179] [PubMed: 19131545]

- Al-Seraihy AS, Owaidah TM, Ayas M, et al.: Clinical characteristics and outcome of children with biphenotypic acute leukemia. Haematologica 94 (12): 1682-90, 2009. [PMC free article: PMC2791935] [PubMed: 19713227]

- Matutes E, Pickl WF, Van't Veer M, et al.: Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia: clinical and laboratory features and outcome in 100 patients defined according to the WHO 2008 classification. Blood 117 (11): 3163-71, 2011. [PubMed: 21228332]

- Hrusak O, de Haas V, Stancikova J, et al.: International cooperative study identifies treatment strategy in childhood ambiguous lineage leukemia. Blood 132 (3): 264-276, 2018. [PubMed: 29720486]

- Orgel E, Alexander TB, Wood BL, et al.: Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia: A cohort and consensus research strategy from the Children's Oncology Group Acute Leukemia of Ambiguous Lineage Task Force. Cancer 126 (3): 593-601, 2020. [PMC free article: PMC7489437] [PubMed: 31661160]

Cytogenetics/Genomics of Childhood ALL

Genomics of childhood ALL

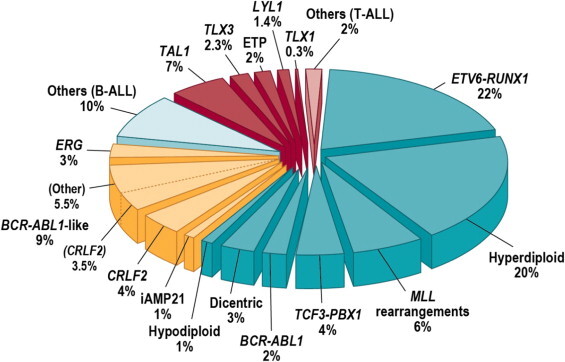

The genomics of childhood ALL has been extensively investigated, and multiple distinctive subtypes have been defined on the basis of cytogenetic and molecular characterizations, each with its own pattern of clinical and prognostic characteristics.[1] Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of ALL cases by cytogenetic/molecular subtype.[1]

Figure 2. Subclassification of childhood ALL. Blue wedges refer to B-progenitor ALL, yellow to recently identified subtypes of B-ALL, and red wedges to T-lineage ALL. Reprinted from Seminars in Hematology, Volume 50, Charles G. Mullighan, Genomic Characterization of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Pages 314–324, Copyright (2013), with permission from Elsevier.

B-ALL cytogenetics/genomics

The genomic landscape of B-ALL is typified by a range of genomic alterations that disrupt normal B-cell development and, in some cases, by mutations in genes that provide a proliferation signal (e.g., activating mutations in RAS family genes or mutations/translocations leading to kinase pathway signaling). Genomic alterations leading to blockage of B-cell development include translocations (e.g., TCF3-PBX1 and ETV6-RUNX1), point mutations (e.g., IKZF1 and PAX5), and intragenic/intergenic deletions (e.g., IKZF1, PAX5, EBF, and ERG).[2]

The genomic alterations in B-ALL tend not to occur at random, but rather to cluster within subtypes that can be delineated by biological characteristics such as their gene expression profiles. Cases with recurring chromosomal translocations (e.g., TCF3-PBX1, ETV6-RUNX1, and KMT2A [MLL]-rearranged ALL) have distinctive biological features and illustrate this point, as do the examples below of specific genomic alterations within distinctive biological subtypes:

- TP53 mutations, often germline, occur at high frequency in patients with low hypodiploid ALL with 32 to 39 chromosomes.[7] TP53 mutations are uncommon in other patients with B-ALL.

Activating point mutations in kinase genes are uncommon in high-risk B-ALL. JAK genes are the primary kinases that are found to be mutated. These mutations are generally observed in patients with Ph-like ALL that have CRLF2 abnormalities, although JAK2 mutations are also observed in approximately 15% of children with Down syndrome ALL.[4,8,9] Several kinase genes and cytokine receptor genes are activated by translocations, as described below in the discussion of Ph+ ALL and Ph-like ALL. FLT3 mutations occur in a minority of cases (approximately 10%) of hyperdiploid ALL and KMT2A-rearranged ALL, and are rare in other subtypes.[10]

Understanding of the genomics of B-ALL at relapse is less advanced than the understanding of ALL genomics at diagnosis. Childhood ALL is often polyclonal at diagnosis and under the selective influence of therapy, some clones may be extinguished and new clones with distinctive genomic profiles may arise.[11] Of particular importance are new mutations that arise at relapse that may be selected by specific components of therapy. As an example, mutations in NT5C2 are not found at diagnosis, whereas specific mutations in NT5C2 were observed in 7 of 44 (16%) and 9 of 20 (45%) cases of B-ALL with early relapse that were evaluated for this mutation in two studies.[11,12] NT5C2 mutations are uncommon in patients with late relapse, and they appear to induce resistance to mercaptopurine (6-MP) and thioguanine.[12] Another gene that is found mutated only at relapse is PRSP1, a gene involved in purine biosynthesis.[13] Mutations were observed in 13.0% of a Chinese cohort and 2.7% of a German cohort, and were observed in patients with on-treatment relapses. The PRSP1 mutations observed in relapsed cases induce resistance to thiopurines in leukemia cell lines. CREBBP mutations are also enriched at relapse and appear to be associated with increased resistance to glucocorticoids.[11,14] With increased understanding of the genomics of relapse, it may be possible to tailor upfront therapy to avoid relapse or detect resistance-inducing mutations early and intervene before a frank relapse.

A number of recurrent chromosomal abnormalities have been shown to have prognostic significance, especially in B-ALL. Some chromosomal alterations are associated with more favorable outcomes, such as high hyperdiploidy (51–65 chromosomes) and the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion. Other alterations historically have been associated with a poorer prognosis, including the Ph chromosome (t(9;22)(q34;q11.2)), rearrangements of the KMT2A gene, hypodiploidy, and intrachromosomal amplification of the AML1 gene (iAMP21).[15]

In recognition of the clinical significance of many of these genomic alterations, the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues lists the following entities for B-ALL:[16]

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, not otherwise specified (NOS).

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with recurrent genetic abnormalities.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2); BCR-ABL1.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(v;11q23.3); KMT2A rearranged.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(12;21)(p13.2;q22.1); ETV6-RUNX1.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with hyperdiploidy.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with hypodiploidy.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(5;14)(q31.1;q32.3); IL3-IGH.

- B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with t(1;19)(q23;p13.3); TCF3-PBX1.

- Provisional entity: B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, BCR-ABL1–like.

- Provisional entity: B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with iAMP21.

These and other chromosomal and genomic abnormalities for childhood ALL are described below.

- Chromosome number.

- High hyperdiploidy (51–65 chromosomes).High hyperdiploidy, defined as 51 to 65 chromosomes per cell or a DNA index greater than 1.16, occurs in 20% to 25% of cases of B-ALL, but very rarely in cases of T-ALL.[17] Hyperdiploidy can be evaluated by measuring the DNA content of cells (DNA index) or by karyotyping. In cases with a normal karyotype or in which standard cytogenetic analysis was unsuccessful, interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) may detect hidden hyperdiploidy.High hyperdiploidy generally occurs in cases with clinically favorable prognostic factors (patients aged 1 to <10 years with a low white blood cell [WBC] count) and is an independent favorable prognostic factor.[17-19] Within the hyperdiploid range of 51 to 65 chromosomes, patients with higher modal numbers (58–66) appeared to have a better prognosis in one study.[19] Hyperdiploid leukemia cells are particularly susceptible to undergoing apoptosis and accumulate higher levels of methotrexate and its active polyglutamate metabolites,[20] which may explain the favorable outcome commonly observed in these cases.While the overall outcome of patients with high hyperdiploidy is considered to be favorable, factors such as age, WBC count, specific trisomies, and early response to treatment have been shown to modify its prognostic significance.[21,22]Patients with trisomies of chromosomes 4, 10, and 17 (triple trisomies) have been shown to have a particularly favorable outcome, as demonstrated by both Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) and Children's Cancer Group analyses of National Cancer Institute (NCI) standard-risk ALL.[23] POG data suggest that NCI standard-risk patients with trisomies of 4 and 10, without regard to chromosome 17 status, have an excellent prognosis.[24]Chromosomal translocations may be seen with high hyperdiploidy, and in those cases, patients are more appropriately risk-classified on the basis of the prognostic significance of the translocation. For instance, in one study, 8% of patients with the Ph chromosome (t(9;22)(q34;q11.2)) also had high hyperdiploidy,[25] and the outcome of these patients (treated without tyrosine kinase inhibitors) was inferior to that observed in non-Ph+ high hyperdiploid patients.Certain patients with hyperdiploid ALL may have a hypodiploid clone that has doubled (masked hypodiploidy).[26] These cases may be interpretable based on the pattern of gains and losses of specific chromosomes (hyperdiploidy with two and four copies of chromosomes rather than three copies). These patients have an unfavorable outcome, similar to those with hypodiploidy.[27]Near triploidy (68–80 chromosomes) and near tetraploidy (>80 chromosomes) are much less common and appear to be biologically distinct from high hyperdiploidy.[28] Unlike high hyperdiploidy, a high proportion of near tetraploid cases harbor a cryptic ETV6-RUNX1 fusion.[28-30] Near triploidy and tetraploidy were previously thought to be associated with an unfavorable prognosis, but later studies suggest that this may not be the case.[28,30]The genomic landscape of hyperdiploid ALL is characterized by mutations in genes of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)/RAS pathway in approximately one-half of cases. Genes encoding histone modifiers are also present in a recurring manner in a minority of cases. Analysis of mutation profiles demonstrates that chromosomal gains are early events in the pathogenesis of hyperdiploid ALL.[31]

- Hypodiploidy (<44 chromosomes).B-ALL cases with fewer than the normal number of chromosomes have been subdivided in various ways, with one report stratifying on the basis of modal chromosome number into the following four groups:[27]

- Near-haploid: 24 to 29 chromosomes (n = 46).

- Low-hypodiploid: 33 to 39 chromosomes (n = 26).

- High-hypodiploid: 40 to 43 chromosomes (n = 13).

- Near-diploid: 44 chromosomes (n = 54).

Most patients with hypodiploidy are in the near-haploid and low-hypodiploid groups, and both of these groups have an elevated risk of treatment failure compared with nonhypodiploid cases.[27,32] Patients with fewer than 44 chromosomes have a worse outcome than do patients with 44 or 45 chromosomes in their leukemic cells.[27] A number of studies have shown that patients with high minimal residual disease (MRD) (≥0.01%) after induction do very poorly, with 5-year event-free survival (EFS) rates ranging from 25% to 47%. Although hypodiploid patients with low MRD after induction fare better (5-year EFS, 64%–75%), their outcomes are still inferior to most children with other types of ALL.[33-35]The recurring genomic alterations of near-haploid and low-hypodiploid ALL appear to be distinctive from each other and from other types of ALL.[7] In near-haploid ALL, alterations targeting RTK signaling, RAS signaling, and IKZF3 are common.[36] In low-hypodiploid ALL, genetic alterations involving TP53, RB1, and IKZF2 are common. Importantly, the TP53 alterations observed in low-hypodiploid ALL are also present in nontumor cells in approximately 40% of cases, suggesting that these mutations are germline and that low-hypodiploid ALL represents, in some cases, a manifestation of Li-Fraumeni syndrome.[7] Approximately two-thirds of patients with ALL and germline pathogenic TP53 variants have hypodiploid ALL.[37]

- Chromosomal translocations and gains/deletions of chromosomal segments.

- t(12;21)(p13.2;q22.1); ETV6-RUNX1 (formerly known as TEL-AML1).Fusion of the ETV6 gene on chromosome 12 to the RUNX1 gene on chromosome 21 is present in 20% to 25% of cases of B-ALL but is rarely observed in T-ALL.[29] The t(12;21)(p13;q22) produces a cryptic translocation that is detected by methods such as FISH, rather than conventional cytogenetics, and it occurs most commonly in children aged 2 to 9 years.[38,39] Hispanic children with ALL have a lower incidence of t(12;21)(p13;q22) than do White children.[40]Reports generally indicate favorable EFS and overall survival (OS) in children with the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion; however, the prognostic impact of this genetic feature is modified by the following factors:[41-45]

- -

Early response to treatment.

- -

NCI risk category (age and WBC count at diagnosis).

- -

Treatment regimen.

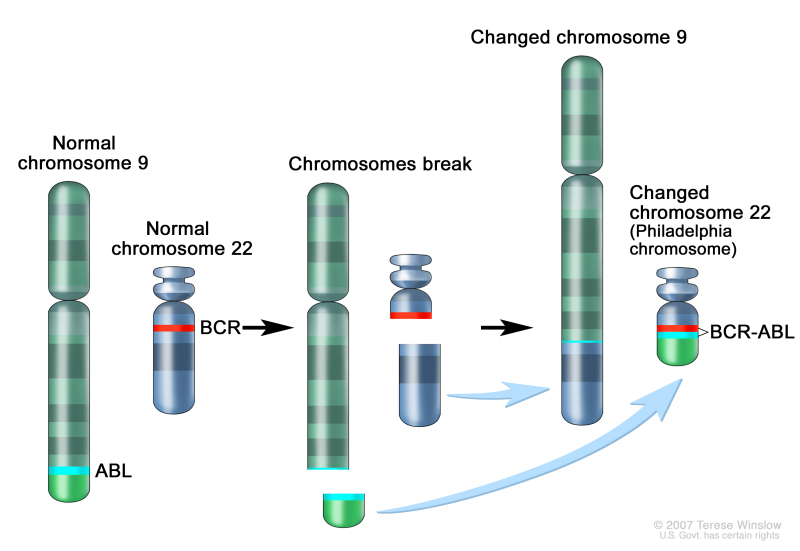

In one study of the treatment of newly diagnosed children with ALL, multivariate analysis of prognostic factors found age and leukocyte count, but not ETV6-RUNX1, to be independent prognostic factors.[41] It does not appear that the presence of secondary cytogenetic abnormalities, such as deletion of ETV6 (12p) or CDKN2A/B (9p), impacts the outcome of patients with the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion.[45,46]There is a higher frequency of late relapses in patients with ETV6-RUNX1 fusions compared with other relapsed B-ALL patients.[41,47] Patients with the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion who relapse seem to have a better outcome than other relapse patients,[48] with an especially favorable prognosis for patients who relapse more than 36 months from diagnosis.[49] Some relapses in patients with t(12;21)(p13;q22) may represent a new independent second hit in a persistent preleukemic clone (with the first hit being the ETV6-RUNX1 translocation).[50,51] - t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2); BCR-ABL1 (Ph+).The Ph chromosome t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2) is present in approximately 3% of children with ALL and leads to production of a BCR-ABL1 fusion protein with tyrosine kinase activity (refer to Figure 3).This subtype of ALL is more common in older children with B-ALL and high WBC count, with the incidence of the t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2) increasing to about 25% in young adults with ALL.Historically, the Ph chromosome t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2) was associated with an extremely poor prognosis (especially in those who presented with a high WBC count or had a slow early response to initial therapy), and its presence had been considered an indication for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in patients in first remission.[25,52-54] Inhibitors of the BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase, such as imatinib mesylate, are effective in patients with Ph+ ALL.[55] A study by the Children's Oncology Group (COG), which used intensive chemotherapy and concurrent imatinib mesylate given daily, demonstrated a 5-year EFS rate of 70% (± 12%), which was superior to the EFS rate of historical controls in the pre-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (imatinib mesylate) era.[56,57]

- t(v;11q23.3); KMT2A-rearranged.Rearrangements involving the KMT2A gene occur in approximately 5% of childhood ALL cases overall, but in up to 80% of infants with ALL. These rearrangements are generally associated with an increased risk of treatment failure.[58-61] The t(4;11)(q21;q23) is the most common rearrangement involving the KMT2A gene in children with ALL and occurs in approximately 1% to 2% of childhood ALL.[59,62]Patients with the t(4;11)(q21;q23) are usually infants with high WBC counts; they are more likely than other children with ALL to have central nervous system (CNS) disease and to have a poor response to initial therapy.[63] While both infants and adults with the t(4;11)(q21;q23) are at high risk of treatment failure, children with the t(4;11)(q21;q23) appear to have a better outcome than either infants or adults.[58,59] Irrespective of the type of KMT2A gene rearrangement, infants with leukemia cells that have KMT2A gene rearrangements have a worse treatment outcome than older patients whose leukemia cells have a KMT2A gene rearrangement.[58,59]

- t(1;19)(q23;p13.3); TCF3-PBX1 and t(17;19)(q22;p13); TCF3-HLF.The t(1;19) occurs in approximately 5% of childhood ALL cases and involves fusion of the TCF3 gene on chromosome 19 to the PBX1 gene on chromosome 1.[66,67] The t(1;19) may occur as either a balanced translocation or as an unbalanced translocation and is the primary recurring genomic alteration of the pre-B–ALL immunophenotype (cytoplasmic immunoglobulin positive).[68] Black children are relatively more likely than White children to have pre-B–ALL with the t(1;19).[69]The t(1;19) had been associated with inferior outcome in the context of antimetabolite-based therapy,[70] but the adverse prognostic significance was largely negated by more aggressive multiagent therapies.[67,71] However, in a trial conducted by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (SJCRH) on which all patients were treated without cranial radiation, patients with the t(1;19) had an overall outcome comparable to children lacking this translocation, with a higher risk of CNS relapse and a lower rate of bone marrow relapse, suggesting that more intensive CNS therapy may be needed for these patients.[72,73]The t(17;19) resulting in the TCF3-HLF fusion occurs in less than 1% of pediatric ALL cases. ALL with the TCF3-HLF fusion is associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation and hypercalcemia at diagnosis. Outcome is very poor for children with the t(17;19), with a literature review noting mortality for 20 of 21 cases reported.[74] In addition to the TCF3-HLF fusion, the genomic landscape of this ALL subtype was characterized by deletions in genes involved in B-cell development (PAX5, BTG1, and VPREB1) and by mutations in RAS pathway genes (NRAS, KRAS, and PTPN11).[68]

- DUX4-rearranged ALL with frequent ERG deletions.Approximately 5% of standard-risk and 10% of high-risk pediatric B-ALL patients have a rearrangement involving DUX4 that leads to its overexpression.[5,6] The frequency in older adolescents (aged >15 years) is approximately 10%. The most common rearrangement produces IGH-DUX4 fusions, with ERG-DUX4 fusions also observed.[75] DUX4-rearranged cases show a distinctive gene expression pattern that was initially identified as being associated with focal deletions in ERG,[75-78] and one-half to more than two-thirds of these cases have focal intragenic deletions involving ERG that are not observed in other ALL subtypes.[5,75] ERG deletions often appear to be clonal, but using sensitive detection methodology, it appears that most cases are polyclonal.[75] IKZF1 alterations are observed in 20% to 40% of DUX4-rearranged ALL.[5,6]ERG deletion connotes an excellent prognosis, with OS rates exceeding 90%; even when the IZKF1 deletion is present, prognosis remains highly favorable.[76-78] While DUX4-rearranged ALL has an overall favorable prognosis, there is uncertainty as to whether this applies to both ERG-deleted and ERG-intact cases. In a study of 50 patients with DUX4-rearranged ALL, patients with ERG deletion detected by genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (n = 33) had a more favorable EFS rate of approximately 90% than did patients with intact ERG (n = 17), with an EFS rate of approximately 70%.

- MEF2D-rearranged ALL.Gene fusions involving MEF2D, a transcription factor that is expressed during B-cell development, are observed in approximately 4% of childhood ALL cases.[79,80] Although multiple fusion partners may occur, most cases involve BCL9, which is located on chromosome 1q21, as is MEF2D.[79,81] The interstitial deletion producing the MEF2D-BCL9 fusion is too small to be detected by conventional cytogenetic methods. Cases with MEF2D gene fusions show a distinctive gene expression profile, except for rare cases with MEF2D-CSFR1 that have a Ph-like gene expression profile.[79,82]The median age at diagnosis for cases of MEF2D-rearranged ALL in studies that included both adult and pediatric patients was 12 to 14 years.[79,80] For 22 children with MEF2D-rearranged ALL enrolled in a high-risk ALL clinical trial, the 5-year EFS rate was 72% (standard error, ± 10%), which was inferior to that for other patients.[79]

- ZNF384-rearranged ALL.ZNF384 is a transcription factor that is rearranged in approximately 4% to 5% of pediatric B-ALL cases.[79,83,84] Multiple fusion partners for ZNF384 have been reported, including ARID1B, CREBBP, EP300, SMARCA2, TAF15, and TCF3. Regardless of the fusion partner, ZNF384-rearranged ALL cases show a distinctive gene expression profile.[79,83,84] ZNF384 rearrangement does not appear to confer independent prognostic significance.[79,83,84] The immunophenotype of B-ALL with ZNF384 rearrangement is characterized by weak or negative CD10 expression, with expression of CD13 and/or CD33 commonly observed.[83,84] Cases of mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) (B/myeloid) that have ZNF384 gene fusions have been reported, [85,86] and a genomic evaluation of MPAL found that ZNF384 gene fusions were present in approximately one-half of B/myeloid cases.[87]

- t(5;14)(q31.1;q32.3); IL3-IGH.This entity is included in the 2016 revision of the WHO classification of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues.[16] The finding of t(5;14)(q31.1;q32.3) in patients with ALL and hypereosinophilia in the 1980s was followed by the identification of the IL3-IGH fusion as the underlying genetic basis for the condition.[88,89] The joining of the IGH locus to the promoter region of the IL3 gene leads to dysregulation of IL3 expression.[90] Cytogenetic abnormalities in children with ALL and eosinophilia are variable, with only a subset resulting from the IL3-IGH fusion.[91]The number of cases of IL3-IGH ALL described in the published literature is too small to assess the prognostic significance of the IL3-IGH fusion. Diagnosis of cases of IL3-IGH ALL may be delayed because it can present with hypereosinophilia in the absence of cytopenias and circulating blasts.[16]

- Intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 (iAMP21).iAMP21 is generally diagnosed using FISH and is defined by the presence of greater than or equal to five RUNX1 signals per cell (or ≥3 extra copies of RUNX1 on a single abnormal chromosome).[16] It occurs in approximately 2% of B-ALL cases and is associated with older age (median, approximately 10 years), presenting WBC of less than 50 × 109/L, a slight female preponderance, and high end-induction MRD.[92-94]The United Kingdom Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (UKALL) clinical trials group initially reported that the presence of iAMP21 conferred a poor prognosis in patients treated in the MRC ALL 97/99 trial (5-year EFS, 29%).[15] In their subsequent trial (UKALL2003 [NCT00222612]), patients with iAMP21 were assigned to a more intensive chemotherapy regimen and had a markedly better outcome (5-year EFS, 78%).[93] Similarly, the COG has reported that iAMP21 was associated with a significantly inferior outcome in NCI standard-risk patients (4-year EFS, 73% for iAMP21 vs. 92% in others), but not in NCI high-risk patients (4-year EFS, 73% vs. 80%).[92] On multivariate analysis, iAMP21 was an independent predictor of inferior outcome only in NCI standard-risk patients.[92] The results of the UKALL2003 and COG studies suggest that treatment of iAMP21 patients with high-risk chemotherapy regimens abrogates its adverse prognostic significance and obviates the need for HSCT in first remission.[94]

- PAX5 alterations.Gene expression analysis identified two distinctive ALL subsets with PAX5 genomic alterations, termed PAX5alt and PAX5 p.Pro80Arg.[95] The alterations in the PAX5alt subtype included rearrangements, sequence mutations, and focal intragenic amplifications.PAX5alt. PAX5 rearrangements have been reported to represent 2% to 3% of pediatric ALL.[96] More than 20 partner genes for PAX5 have been described,[95] with PAX5-ETV6, the primary genomic alteration in dic(9;12)(p13;p13),[97] being the most common gene fusion.[95]Intragenic amplification of PAX5 was identified in approximately 1% of B-ALL cases, and it was usually detected in cases lacking known leukemia-driver genomic alterations.[98] Cases with PAX5 amplification show male predominance (66%), with most (55%) having NCI high-risk status. For a cohort of patients with PAX5 amplification diagnosed between 1993 and 2015, the 5-year EFS rate was 49% (95% confidence interval [CI], 36%–61%), and the OS rate was 67% (95% CI, 54%–77%), suggesting a relatively poor prognosis for this B-ALL subtype.PAX5 p.Pro80Arg. PAX5 with a p.Pro80Arg mutation shows a gene expression profile distinctive from that of other cases with PAX5 alterations.[95] Cases with PAX5 p.Pro80Arg appear to be more common in the adolescent and young adult (AYA) and adult populations (3%–4% frequency) than in children with NCI standard-risk or high-risk ALL (0.4% and 1.9% frequency, respectively). Outcome for the pediatric patients with PAX5 p.Pro80Arg and PAX5alt treated on a COG clinical trial appears to be intermediate (5-year EFS, approximately 75%).[95]

- Ph-like (BCR-ABL1-like).BCR-ABL1–negative patients with a gene expression profile similar to BCR-ABL1–positive patients have been referred to as Ph-like.[99-101] This occurs in 10% to 20% of pediatric ALL patients, increasing in frequency with age, and has been associated with an IKZF1 deletion or mutation.[8,99,100,102,103]Retrospective analyses have indicated that patients with Ph-like ALL have a poor prognosis.[4,99] In one series, the 5-year EFS for NCI high-risk children and adolescents with Ph-like ALL was 58% and 41%, respectively.[4] While it is more frequent in older and higher-risk patients, the Ph-like subtype has also been identified in NCI standard-risk patients. In a COG study, 13.6% of 1,023 NCI standard-risk B-ALL patients were found to have Ph-like ALL; these patients had an inferior EFS compared with non–Ph-like standard-risk patients (82% vs. 91%), although no difference in OS (93% vs. 96%) was noted.[104] In one study of 40 Ph-like patients, the adverse prognostic significance of this subtype appeared to be abrogated when patients were treated with risk-directed therapy on the basis of MRD levels.[105]The hallmark of Ph-like ALL is activated kinase signaling, with 50% containing CRLF2 genomic alterations [101,106] and half of those cases containing concomitant JAK mutations.[107]Many of the remaining cases of Ph-like ALL have been noted to have a series of translocations with a common theme of involvement of kinases, including ABL1, ABL2, CSF1R, JAK2, and PDGFRB.[4,102] Fusion proteins from these gene combinations have been noted in some cases to be transformative and have responded to tyrosine kinase inhibitors both in vitro and in vivo,[102] suggesting potential therapeutic strategies for these patients. The prevalence of targetable kinase fusions in Ph-like ALL is lower in NCI standard-risk patients (3.5%) than in NCI high-risk patients (approximately 30%).[104] Point mutations in kinase genes, aside from those in JAK1 and JAK2, are uncommon in Ph-like ALL cases.[8]Approximately 9% of Ph-like ALL cases result from rearrangements that lead to overexpression of a truncated erythropoietin receptor (EPOR).[108] The C-terminal region of the receptor that is lost is the region that is mutated in primary familial congenital polycythemia and that controls stability of the EPOR. The portion of the EPOR remaining is sufficient for JAK-STAT activation and for driving leukemia development.CRLF2. Genomic alterations in CRLF2, a cytokine receptor gene located on the pseudoautosomal regions of the sex chromosomes, have been identified in 5% to 10% of cases of B-ALL; they represent approximately 50% of cases of Ph-like ALL.[109-111] The chromosomal abnormalities that commonly lead to CRLF2 overexpression include translocations of the IGH locus (chromosome 14) to CRLF2 and interstitial deletions in pseudoautosomal regions of the sex chromosomes, resulting in a P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion.[8,106,109,110] These two genomic alterations are associated with distinctive clinical and biological characteristics.The P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion is observed in 70% to 75% of pediatric patients with CRLF2 genomic alterations, and it occurs in younger patients (median age, approximately 4 years vs. 14 years for patients with IGH-CRLF2).[112,113] P2RY8-CRLF2 occurs not infrequently with established chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., hyperdiploidy, iAMP21, dic(9;20)), while IGH-CRLF2 is generally mutually exclusive with known cytogenetic subgroups. CRLF2 genomic alterations are observed in approximately 60% of patients with Down syndrome ALL, with P2RY8-CRLF2 fusions being more common than IGH-CRLF2 (approximately 80% vs. 20%).[110,112]IGH-CRLF2 and P2RY8-CRLF2 commonly occur as an early event in B-ALL development and show clonal prevalence.[114] However, in some cases they appear to be a late event and show subclonal prevalence.[114] Loss of the CRLF2 genomic abnormality in some cases at relapse confirms the subclonal nature of the alteration in these cases.[112,115]CRLF2 abnormalities are strongly associated with the presence of IKZF1 deletions. Other recurring genomic alterations found in association with CRLF2 alterations include deletions in genes associated with B-cell differentiation (e.g., PAX5, BTG1, EBF1, etc.) and cell cycle control (CDKN2A), as well as genomic alterations activating JAK-STAT pathway signaling (e.g., IL7R and JAK mutations).[4,106,107,110,116]Although the results of several retrospective studies suggest that CRLF2 abnormalities may have adverse prognostic significance in univariate analyses, most do not find this abnormality to be an independent predictor of outcome.[106,109,110,117,118] For example, in a large European study, increased expression of CRLF2 was not associated with unfavorable outcome in multivariate analysis, while IKZF1 deletion and Ph-like expression signatures were associated with unfavorable outcome.[103] Controversy exists about whether the prognostic significance of CRLF2 abnormalities should be analyzed on the basis of CRLF2 overexpression or on the presence of CRLF2 genomic alterations.[117,118]

- IKZF1 deletions.IKZF1 deletions, including deletions of the entire gene and deletions of specific exons, are present in approximately 15% of B-ALL cases. Less commonly, IKZF1 can be inactivated by deleterious point mutations.[100]Cases with IKZF1 deletions tend to occur in older children, have a higher WBC count at diagnosis, and are therefore, more common in NCI high-risk patients than in NCI standard-risk patients.[2,100,116,119] A high proportion of Ph-like cases have a deletion of IKZF1,[3,116] and ALL arising in children with Down syndrome appears to have elevated rates of IKZF1 deletions.[120] IKZF1 deletions are also common in cases with CRLF2 genomic alterations and in Ph-like ALL.[76,99,116]Multiple reports have documented the adverse prognostic significance of an IKZF1 deletion, and most studies have reported that this deletion is an independent predictor of poor outcome in multivariate analyses.[76,99,100,103,116,121-127]; [128][Level of evidence: 2Di] However, the prognostic significance of IKZF1 may not apply equally across ALL biological subtypes, as illustrated by the apparent lack of prognostic significance in patients with ERG deletion.[76-78] Similarly, the prognostic significance of the IKZF1 deletion also appeared to be minimized in a cohort of COG patients with DUX4-rearranged ALL and with ERG transcriptional dysregulation that frequently occurred by ERG deletion.[6] The Associazione Italiana di Ematologia e Oncologia Pediatrica (AIEOP)–Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM) group reported that IKZF1 deletions were significant adverse prognostic factors only in B-ALL patients with high end-induction MRD and in whom co-occurrence of deletions of CDKN2A, CDKN2B, PAX5, or PAR1 (in the absence of ERG deletion) were identified.[129]There are few published results of changing therapy on the basis of IKZF1 gene status. The Malaysia-Singapore group published results of two consecutive trials. In the first trial (MS2003), IKZF1 status was not considered in risk stratification, while in the subsequent trial (MS2010), IKZF1-deleted patients were excluded from the standard-risk group. Thus, more IKZF1-deleted patients in the MS2010 trial received intensified therapy. Patients with IKZF1-deleted ALL had improved outcomes in MS2010 compared with patients in MS2003, but interpretation of this observation is limited by other changes in risk stratification and therapeutic differences between the two trials.[130][Level of evidence: 2A]

T-ALL cytogenetics/genomics

T-ALL is characterized by genomic alterations leading to activation of transcriptional programs related to T-cell development and by a high frequency of cases (approximately 60%) with mutations in NOTCH1 and/or FBXW7 that result in activation of the NOTCH1 pathway.[131] In contrast to B-ALL, the prognostic significance of T-ALL genomic alterations is less well-defined. Cytogenetic abnormalities common in B-lineage ALL (e.g., hyperdiploidy, 51–65 chromosomes) are rare in T-ALL.[132,133]

- Notch pathway signaling.Notch pathway signaling is commonly activated by NOTCH1 and FBXW7 gene mutations in T-ALL, and these are the most commonly mutated genes in pediatric T-ALL.[131,134] NOTCH1-activating gene mutations occur in approximately 50% to 60% of T-ALL cases, and FBXW7-inactivating gene mutations occur in approximately 15% of cases, with the result that approximately 60% of cases have Notch pathway activation by mutations in at least one of these genes.[135]The prognostic significance of NOTCH1/FBXW7 mutations may be modulated by genomic alterations in RAS and PTEN. The French Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia Study Group (FRALLE) and the Group for Research on Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia groups reported that patients having mutated NOTCH1/FBXW7 and wild-type PTEN/RAS constituted a favorable-risk group while patients with PTEN or RAS mutations, regardless of NOTCH1/FBXW7 status, have a significantly higher risk of treatment failure.[136,137] In the FRALLE study, 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse and disease-free survival (DFS) were 50% and 46% for patients with mutated NOTCH1/FBXW7 and mutated PTEN/RAS versus 13% and 87% for patients with mutated NOTCH1/FBXW7 and wild-type PTEN/RAS.[136] The overall 5-year DFS in the FRALLE study was 73%, and additional research is needed to determine whether the same prognostic significance for NOTCH1/FBXW7 and PTEN/RAS mutations will apply to current treatment regimens, which produce overall 5-year DFS rates that approach 90%.[138]

- Chromosomal translocations.Multiple chromosomal translocations have been identified in T-ALL that lead to deregulated expression of the target genes. These chromosome rearrangements fuse genes encoding transcription factors (e.g., TAL1/TAL2, LMO1 and LMO2, LYL1, TLX1, TLX3, NKX2-I, HOXA, and MYB) to one of the T-cell receptor loci (or to other genes) and result in deregulated expression of these transcription factors in leukemia cells.[131,132,139-143] These translocations are often not apparent by examining a standard karyotype, but can be identified using more sensitive screening techniques, including FISH or PCR.[132] Mutations in a noncoding region near the TAL1 gene that produce a super-enhancer upstream of TAL1 represent nontranslocation genomic alterations that can also activate TAL1 transcription to induce T-ALL.[144]Translocations resulting in chimeric fusion proteins are also observed in T-ALL.[136]

- A NUP214-ABL1 fusion has been noted in 4% to 6% of T-ALL cases and is observed in both adults and children, with a male predominance.[145-147] The fusion is cytogenetically cryptic and is seen in FISH on amplified episomes or, more rarely, as a small homogeneous staining region.[147] T-ALL may also uncommonly show ABL1 fusion proteins with other gene partners (e.g., ETV6, BCR, and EML1).[147] ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib or dasatinib, may demonstrate therapeutic benefits in this T-ALL subtype,[145,146,148] although clinical experience with this strategy is very limited.[149-151]

- Gene fusions involving SPI1 (encoding the transcription factor PU.1) were reported in 4% of Japanese children with T-ALL.[152] Fusion partners included STMN1 and TCF7. T-ALL cases with SPI1 fusions had a particularly poor prognosis; six of seven affected individuals died within 3 years of diagnosis of early relapse.

- Other recurring gene fusions in T-ALL patients include those involving MLLT10, KMT2A, and NUP98.[131]

Early T-cell precursor ALL cytogenetics/genomics

Detailed molecular characterization of early T-cell precursor ALL showed this entity to be highly heterogeneous at the molecular level, with no single gene affected by mutation or copy number alteration in more than one-third of cases.[153] Compared with other T-ALL cases, the early T-cell precursor group had a lower rate of NOTCH1 mutations and significantly higher frequencies of alterations in genes regulating cytokine receptors and RAS signaling, hematopoietic development, and histone modification. The transcriptional profile of early T-cell precursor ALL shows similarities to that of normal hematopoietic stem cells and myeloid leukemia stem cells.[153]

Studies have found that the absence of biallelic deletion of the TCR-gamma locus (ABD), as detected by comparative genomic hybridization and/or quantitative DNA-PCR, was associated with early treatment failure in patients with T-ALL.[154,155] ABD is characteristic of early thymic precursor cells, and many of the T-ALL patients with ABD have an immunophenotype consistent with the diagnosis of early T-cell precursor phenotype.

Mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) cytogenetics/genomics

For acute leukemias of ambiguous lineage, the WHO classification system is summarized in Table 3.[156,157] The criteria for lineage assignment for a diagnosis of MPAL are provided in Table 4.[16]

Table 3. Acute Leukemias of Ambiguous Lineage According to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissuesa

| Condition | Definition |