NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Review question: What advice should be given to women at discharge from maternity care to reduce their risk for developing recurrent hypertension during a subsequent pregnancy, and their risk of longer term cardiovascular disease?

Introduction

Women who have had a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy are at an increased risk of developing hypertensive disorders in a subsequent pregnancy, as well as high blood pressure in later life, and associated cardiovascular complications.

The aim of this review is to determine the prevalence of recurrent hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, as well as the likelihood of future cardiovascular disease, so that women can be made aware of these risks and given advice to reduce them.

Summary of the protocol

Please see Table 1 for a summary of the population, exposure/prognostic factor, confounders, comparison, and outcome characteristics of this review.

Table 1

Summary of the protocol.

For full details see the review protocol in appendix A.

Methods and process

This evidence review was developed using the methods and process described in Developing NICE guidelines: the manual 2014. Methods specific to this review question are described in the review protocol in appendix A.

Declaration of interests were recorded according to NICE’s 2018 conflicts of interest policy (see Register of interests).

Clinical evidence

This systematic review identifies the risk for women who have had a hypertensive disorder during pregnancy (including pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension or chronic hypertension) of developing cardiovascular disease at any future date, including cardiovascular mortality, stroke and hypertension. It also considers the risk for women who have had a hypertensive disorder during pregnancy of having a hypertensive disorder during a future pregnancy.

Definitions of hypertensive disorders differed between studies. Some studies grouped women with any hypertensive disorder together, including pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension and sometimes chronic hypertension, (Callaway 2013, Canoy 2016, Ehrenthal 2015, Hermes 2013, Mito 2018, Nzelu 2018, Tooher 2013, Tooher 2016, Yeh 2014). Other studies focused on specific groups of women, for example women with pre-eclampsia only, (Auger 2016, Bellamy 2007, Benschop 2018, Boghossian 2015, Bokslag 2017, Bramham 2011, Drost 2012, Ebbing 2016, Li 2014, Mahande 2013, Mannisto 2013, McDonald 2008, McDonald 2013, Melamed 2012, Mongraw-Chaffin 2010, Scholten 2013, Tooher 2017, Wu 2017). The remaining studies provided separate analyses for women with any hypertensive disorder and women with specific hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in the same report (Black 2016, Grandi 2017, van Oostwaard 2015). The majority of studies provided no details to indicate the severity of hypertensive disease during pregnancy (such as severity of hypertension, or gestational age at onset/delivery).

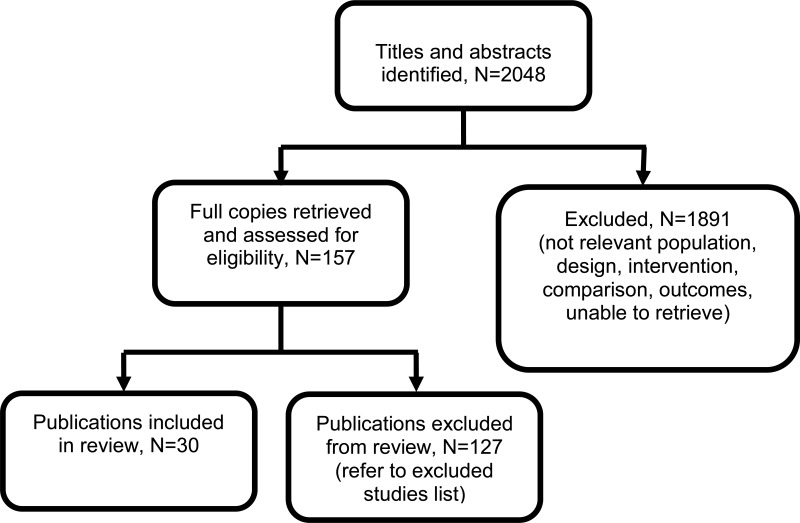

Included studies

For long-term cardiovascular outcomes, 19 observational studies and 3 systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been included (Auger 2017, Bellamy 2007, Benschop 2018, Black 2016, Bokslag 2017, Callaway 2013, Canoy 2016, Drost 2012, Ehrenthal 2015, Grandi 2017, Hermes 2013, Mannisto 2013, McDonald 2008, McDonald 2013, Mito 2018, Mongraw-Chaffin 2010, Scholten 2013, Tooher 2013, Tooher 2016, Tooher 2017, Wu 2017, Yeh 2014).

For recurrence of any hypertensive disorder during subsequent pregnancies, 7 observational studies and 1 Individual Patient Data (IPD) meta-analysis have been included (Boghossian 2015, Bramham 2011, Ebbing 2016, Li 2014, Mahande 2013, Melamed 2012, Nzelu 2018, van Oostwaard 2015).

See also the literature search strategy in appendix B and study selection flow chart in appendix C.

Excluded studies

Studies not included in this review with reasons for their exclusions are provided in appendix K

Summary of clinical studies included in the evidence review

Table 2 provides a brief summary of the included studies for the studies reporting on long-term outcomes at any future date, and Table 3 provides a brief summary of the included studies reporting on recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Table 2

Summary of included studies reporting on long-term outcomes at any future date.

Table 3

Summary of included studies reporting on recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

See appendix D for full evidence tables.

Quality assessment of clinical studies included in the evidence review

See appendix F for the quality assessment of the included studies.

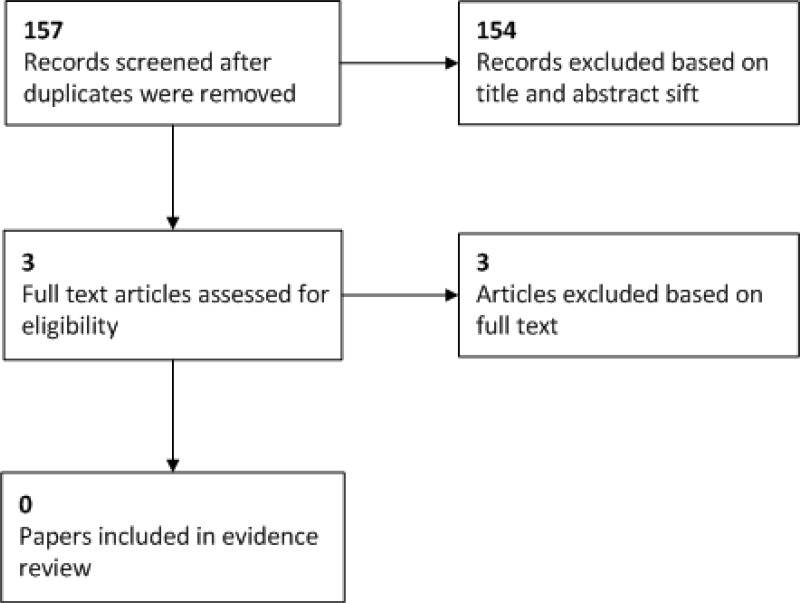

Economic evidence

No economic evidence on the cost effectiveness of advice on discharge was identified by the systematic search of the economic literature undertaken for this guideline. Economic modelling was not undertaken for this question because other topics were agreed as higher priorities for economic evaluation.

Evidence statements

Long-term outcomes

Long-term outcomes at any future date in women with any hypertensive disorder during pregnancy

Cardiovascular disease

- Three retrospective cohort studies (n =1 258 616) provided low to high quality evidence to show that women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy had:

- a prevalence of cardiovascular disease between 5.39% and 7.44% and an incidence of 9.74 per 1000 women/year.

- an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease when compared to women with no hypertensive disorder during pregnancy. Low quality evidence from a single study reported a relative risk of 1.29 and high quality evidence from a second study reported a hazard ratio of 2.3.

Cardiovascular mortality

- Two retrospective cohort studies (n =1 137 217) provided low to moderate quality evidence to show that women with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy had:

- mortality from coronary heart disease of 0.87%, and mortality from cerebrovascular disease of 0.52%.

- an increased risk of death from coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease (RR 1.35 and 1.16, respectively) when compared to women who did not have hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

- an increased risk of death from ischemic heart disease (OR 1.93).

Stroke

- Two retrospective cohort studies (n=1 150 125) provided very low to low quality evidence to show that women with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy had:

- a prevalence of stroke in later life of 2.33%.

- an increased risk of stroke in later life when compared to women with no hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (low quality evidence from one study showed a RR of 1.23, very low quality evidence from a second study showed RR of between 1.46 and 1.69).

Hypertension

- Seven observational studies (n=206 524) provided very low to high quality evidence to show that women with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy had:

- a prevalence of hypertension between 12.53% and 33%, and an incidence of 24.93 per 1000 women/year.

- an increased risk of hypertension as compared to women who did not have hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. Reported odds ratios ranged from 2.46 to 7.1 (high quality evidence from two studies, very low quality evidence from one study). High quality evidence from two further studies showed a relative risk of 2.30 and a hazard ratio of 4.6, respectively, for the occurrence of hypertension in women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Analysis according to gestational age at birth

- One prospective cohort study (n=405) provided moderate quality evidence to show that women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy who gave birth after 37 weeks had a prevalence of hypertension in later life of 34% and increased odds for developing hypertension, as compared with women who did not have hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, with an odds ratio of 47.5.

Long-term outcomes in women with pre-eclampsia at index pregnancy

Cardiovascular disease

- One retrospective cohort study (n=573 327) provided high quality evidence to show that women with recurrent pre-eclampsia (parity ≥ 2) were at higher risk of cardiovascular disease, with a hazard ratio of 3.9, relative to women with no pre-eclampsia (any parity). The risk was also elevated for women with pre-eclampsia in their only pregnancy (parity = 1), with a hazard ratio of 3.1, relative to women with no pre-eclampsia (parity ≥ 2).

- Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses (n=4 358 098) and one observational study (n=1158) provided high quality evidence to show that women who have had pre-eclampsia were at increased risk of cardiovascular disease later in life (RR ranging from 2.33 to 2.50 and OR 2.67, respectively). One further retrospective cohort study (n = 146 748) provided high quality evidence to show no significant difference in the risk of cardiovascular disease for women with a history of pre-eclampsia.

Mortality due to cardiovascular disease

- Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses (n=2 802 247) and one prospective cohort studies (n=14 403) provided moderate to high quality evidence to show that women who have had pre-eclampsia were at increased risk of mortality due to cardiovascular disease later in life (RR ranging from 2.21 to 2.29 and HR 2.14, respectively).

Analysis according to gestational age at birth

- One prospective cohort study (n=14403) provided high quality evidence to show that women who have had pre-eclampsia and gave birth at <34 weeks had an increased risk of mortality due to cardiovascular disease later in life (HR 9.54).

Stroke

- One retrospective cohort study (n=573 327) provided high quality evidence to show that women with recurrent pre-eclampsia (parity ≥ 2) were at higher risk of stroke, with a hazard ratio of 3, relative to women with no pre-eclampsia (any parity). The risk was also elevated for women with pre-eclampsia in their only pregnancy (parity =1), with a hazard ratio of 3.1, relative to women with no pre-eclampsia (parity ≥ 2).

- Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses (n=6 420 769) and one retrospective cohort study (n=146748) provided moderate to high quality evidence to show that women who have had pre-eclampsia were at higher risk of developing stroke later in life (RR ranging from 1.81 to 2.03, and HR 5.2, respectively). One further retrospective cohort study (n=1158) provided high quality evidence to show that women who have had pre-eclampsia at their index pregnancy were not at higher risk of developing stroke later in life.

Hypertension

- One retrospective cohort study (n=573 327) provided high quality evidence to show that women with recurrent pre-eclampsia (parity ≥ 2) were at higher risk of hypertension, with a hazard ratio of 7.2, relative to women with no pre-eclampsia (any parity). The risk was also elevated for women with pre-eclampsia in their only pregnancy (parity = 1), with a hazard ratio of 4.8, relative to women with no pre-eclampsia (parity ≥ 2).

- One systematic review and meta-analysis (n=19744) and 3 observational studies including n= 33049 women provided moderate to high quality evidence to show that women who have had pre-eclampsia had:

- a prevalence of hypertension between 12.8% and 22.8%.

- an increased risk of hypertension in later life, with reported relative risk of 2.23 to 3.70, and odds ratio of 3.06, respectively.

Analysis according to gestational age at birth

- One retrospective cohort study including n= 1297 women provided moderate quality evidence to show that the prevalence of hypertension in later life increased according to gestational age at birth, with women who gave birth at lower gestational ages having a greater prevalence of hypertension (prevalence 32.1% for women who gave birth <28 weeks, as compared with prevalence of 18.3% for women who gave birth >37 weeks).

- Three observational studies including n= 1058 women provided high to moderate quality evidence to show that women with a history of early onset pre-eclampsia (<34 weeks):

- had a prevalence of hypertension in later life between 24% and 38.2%.

- the odds of developing hypertension were increased (high quality evidence from one study showed an OR of 3.59), as compared with women who did not have pre-eclampsia.

Long-term outcomes in women with gestational hypertension at index pregnancy

Cardiovascular disease

- Two observational studies (n= 30 321) provided high quality evidence to show that women who have had gestational hypertension at their index pregnancy were at increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease (OR 3.19, HR 1.45).

Stroke

- Two observational studies (n= 30 321) provided high quality evidence to show uncertainty regarding the effect of gestational hypertension on the risk of stroke. One study showed an increased risk of stroke in later life (HR 1.59) and the second showed no significant change in the risk (OR 0.57).

Hypertension

Two observational studies (n= 36 873) showed that women who have had gestational hypertension at their index pregnancy were at increased risk of hypertension (HR 2.53; OR 4.08, respectively) later in life.

Long-term outcomes in women with chronic hypertension at their index pregnancy

Cardiovascular disease

- One prospective cohort study (n=1901) provided high quality evidence to show that women who have had chronic hypertension at their index pregnancy:

- had a prevalence of cardiovascular disease later in life of 50.43%.

- were at increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease (HR 1.66) later in life.

Stroke

- One prospective cohort study (n=1901) provided high quality evidence to show that women who have had chronic hypertension at their index pregnancy:

- had a prevalence of (ischaemic) stroke of 12.9% later in life.

- were at increased risk of developing ischaemic stroke (HR 1.80) later in life.

Hypertension

- One prospective cohort study including n= 8453 women provided high quality evidence to show that women who have had chronic hypertension at their index pregnancy had a prevalence of hypertension of 62.1% later in life.

Recurrence

Recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in women with any hypertensive disorder at index pregnancy

Pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension

- One retrospective cohort study and 1 individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis including n= 100 586 women provided high quality evidence to show that:

- the prevalence of pre-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancies ranged between 12.54% and 13.8%.

- the prevalence of gestational hypertension in subsequent pregnancies ranged between 8.6% and 22.4%.

Any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy

- One retrospective cohort study and 1 IPD meta-analysis including n= 100 586 women provided high quality evidence to show that the prevalence of any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy in subsequent pregnancies ranged from 20.7% to 35%.

Recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy at subsequent pregnancies in women with pre-eclampsia at index pregnancy

Pre-eclampsia

- Three observational studies and 1 IPD meta-analysis (n=127 655) provided moderate to high quality evidence to show that the overall recurrence of pre-eclampsia was between 5.9% and 59.8% for women who had pre-eclampsia at their index pregnancy.

Analysis according to gestational age at birth in the index pregnancy

- Two observational studies (n=763 527) provided high to moderate quality evidence to show that the recurrence of pre-eclampsia was between 12.86% and 24.6% in women who had pre-eclampsia and gave birth at >37 weeks during their index pregnancy.

- Two observational studies (n=763 527) provided moderate quality evidence to show that the recurrence of pre-eclampsia was between 22.98% and 23.97% in women who had pre-eclampsia and gave birth at 34 to 36+6 weeks during their index pregnancy.

- Two observational studies (n=763 527) provided moderate quality evidence to show that the recurrence of pre-eclampsia was between 32.86% and 34.89% in women who have had pre-eclampsia and gave birth at 28 to 33+6 weeks during their index pregnancy.

Gestational hypertension

- One retrospective cohort study and one IPD meta-analysis (n=126 378) provided high to moderate quality evidence to show that the occurrence of gestational hypertension was between 6% and 11.82% in women who had pre-eclampsia during their index pregnancy.

Analysis according to gestational age at birth in the index pregnancy

- One observational study (n=742 980) provided moderate quality evidence to show that the occurrence of gestational hypertension was 6.24% in women who had pre-eclampsia at their index pregnancy and gave birth at >37 weeks.

- Two observational studies (n=743 780) provided moderate quality evidence to show that the occurrence of gestational hypertension was between 7.4% and 43.36% in women who had pre-eclampsia and gave birth at between 34 and 36+6 weeks during their index pregnancy.

- Two observational studies (n=743 780) provided moderate quality evidence to show that the occurrence of gestational hypertension was between 6.52% and 53.28% in women who had pre-eclampsia and gave birth between 28 and 33+6weeks during their index pregnancy.

Chronic hypertension

- One observational study (n=26963) provided moderate quality evidence to show that the occurrence of chronic hypertension was 1.9% in women who had pre-eclampsia during their index pregnancy.

Any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy

- One IPD meta-analysis (n=99415) provided high quality evidence to show that the occurrence of any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy in women who had pre-eclampsia in their index pregnancy was 20.4%.

Recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy at subsequent pregnancies in women with gestational hypertension at index pregnancy

Pre-eclampsia

- Three observational studies and 1 IPD meta-analysis (n=870 410) provided moderate to high quality evidence to show that the occurrence of pre-eclampsia in women who had gestational hypertension during their index pregnancy was between 5.6% and 8%.

Gestational hypertension

- Two observational studies and 1 IPD meta-analysis (n=869 358) provided moderate to high quality evidence to show that the recurrence of gestational hypertension was between 10.83% and 14.5%.

Chronic hypertension

- One observational study (n=26830) provided moderate quality evidence to show that the occurrence of chronic hypertension in subsequent pregnancy was 2.9% in women who have had gestational hypertension at their index pregnancy.

Any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy

- One IPD meta-analysis (n = 99415) provided high quality evidence to show that the recurrence of any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy was 21.5% in women who had gestational hypertension during their index pregnancy.

Recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy at subsequent pregnancies in women with chronic hypertension at index pregnancy

Pre-eclampsia

- One prospective cohort study (n=3909) provided high quality evidence to show that the occurrence of pre-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancies was 28.6% in women who had chronic hypertension at their index pregnancy.

Chronic hypertension

- One retrospective cohort study (n=26 963) provided moderate quality evidence to show that the recurrence of chronic hypertension (including superimposed pre-eclampsia) was 100% in women who had chronic hypertension at their index pregnancy.

The committee’s discussion of the evidence

Interpreting the evidence

The outcomes that matter most

The review aimed to identify 2 groups of outcomes: the risk of longer term cardiovascular disease (such as myocardial infarction, heart disease or a major adverse cardiovascular event, stroke or hypertension) and the risk of developing a recurrent hypertensive disorder of pregnancy during a subsequent pregnancy. The risk of any of these outcomes occurring was thought to be important to women, so all outcomes were given an equal level of importance and were not prioritised by the committee.

The quality of the evidence

The evidence consisted of 3 systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 1 individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis and 26 observational studies. The included studies were critically appraised using the Quality in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) tool for prognostic studies or the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool for systematic reviews. The overall risk of bias of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses and the IPD meta-analysis was low, and the quality was therefore high. The quality of the 26 observational studies ranged from very low to high. The main quality issues noted were as follows:

- -

the approach to measure prognostic factors and outcomes was not always reliable, as some studies obtained this information through questionnaires completed at recruitment.

- -

the approach to measure outcomes was not always reliable, as this was based on whether women were taking or not taking antihypertensive medication rather than based on a clinical assessment.

- -

some studies reported significant loss-to-follow up, without any reasons provided.

For the recurrence rates of hypertensive disorders the committee noted that there was a large variation in the reported prevalence rates. The committee discussed that this may be due to variation in the conduct of the observational studies identified. Different ways of measuring outcomes (for example, such as measured hypertension, the need for anti-hypertensive medication, participant reporting of hypertension) may also have contributed to the variety of effect sizes. Furthermore, settings in which the studies were conducted were not always generalizable to the UK population.

The studies included used a variety of outcome measures to assess longer term outcomes, including risk ratios (RR), hazard ratios (HR) and odds ratios (OR). This made direct comparison of effect sizes between studies challenging. Furthermore, the duration of follow up varied widely between the studies. For example, some studies measured the occurrence of hypertension just one year after birth (Benschop 2018, Black 2016, Erenthral 2015, Scholten 2013) whilst others had follow up times of 20-40 years (Callaway 2013, Mannisto 2013, McDonald 2013). The background rate of these long term outcomes will change markedly over an individual’s lifetime, and caused some difficulty in interpreting these varied studies.

In order to provide overall estimates of the risk of long term cardiovascular disorders, and the prevalence of future hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, the committee gave more weight to evidence from larger studies (>1000 participants). The results from smaller studies were thought to be at higher risk of bias, due to random error. Evidence from the studies including >1000 participants was used to inform the recommendations in tables 4 and 5, to summarise the likely risks for future cardiovascular health and recurrence of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. The recommendations reflect the range of risk estimates reported by these larger studies. Due to the variation in follow up periods, reporting of an absolute, background risk was not possible for table 5. Instead, the table is designed to give an overall summary of the evidence, to inform women and health care professionals of the estimated risk.

Benefits and harms

Recurrence

The evidence for the recurrence rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy was presented as prevalence rates, and to put this into context the committee discussed what the ‘expected’ rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were. For example, pre-eclampsia occurs in approximately 2-3% of pregnant women overall, but prevalence rates of pre-eclampsia in women with any previous hypertensive disorder of pregnancy ranged from 12.5 to 13.8%, and in women with a previous history of pre-eclampsia ranged from 6% to 60%. Similarly, the ‘expected’ rate of gestational hypertension was approximately 8% but in women with any previous hypertensive disorder of pregnancy it ranged from 8.6 to 22.4%. Overall the majority of studies showed an increased recurrence in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in women with a history of hypertensive disorders.

The evidence on recurrence also indicated that prevalence rates were higher in certain subgroups of women. For example, women with a history of pre-eclampsia who gave birth at an earlier gestational age were more likely to develop pre-eclampsia in a subsequent pregnancy than women who had given birth at a later gestational age.

The committee discussed the usefulness of knowing the prevalence rates and how this information would help women, and agreed that women who have experienced hypertensive disorders during pregnancy should be advised about the risk of recurrence. This could impact on their decisions regarding family planning. It also allows for appropriate surveillance and monitoring during future pregnancies, to identify developing or worsening hypertension.

The committee highlighted two possible harms associated with the recommendations. The first one was related to information provision: information about recurrence risks may be given to women when it is not wanted, and this may cause distress. For this reason, information should be given in a timely manner, should ideally form part of pre-pregnancy counselling, and should be provided by someone who is skilled in helping women interpret the risks. Another issue the committee raised was in relation to fragmented care: currently, the provision of care for postnatal women crosses disciplines, with primary care, midwifery, and obstetric teams being involved, and ideally interventions and information should be consistently delivered by the same person, avoiding duplication and inconsistency.

Long-term cardiovascular risk

Although it was difficult to combine results from different studies, and despite the heterogeneous nature of the studies, the majority of studies found that the presence of a hypertensive disorder during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of long-term cardiovascular morbidity. This was true for studies looking at any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, and for the three individual disorders (chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia). The increase was seen for all the outcomes of interest: cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular mortality, stroke and hypertension. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease can have a significant impact on the quality and length of life and the committee therefore agreed that women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be advised of this higher risk of cardiovascular disease. The committee also discussed that in order to reduce the risk of future cardiovascular disease in these women it would be necessary to identify modifiable risk factors and offer interventions to reduce future risk.

The committee discussed the possible interventions which may modify the risk of cardiovascular disease in women who have had hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. They noted that there are well recognised, modifiable risk factors which may help to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disorders (such as keeping BMI at a healthy level and reducing or stopping smoking). However, the committee also noted that the majority of evidence in this area comes from the wider population, particularly from studies of older males. Therefore this evidence may not be directly applicable to the population of younger women who have recently given birth. Furthermore, the committee noted that interventions which may address these risk factors (such as exercise classes and smoking cessation advice) have not been specifically assessed for efficacy in this group of women. In the absence of specific evidence in this group of women, the committee agreed that it was reasonable to cross-refer to general lifestyle modifications and so included a reference to existing NICE guidelines on stopping smoking, and healthy lifestyle interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease and manage weight and diabetes in pregnancy. However, as there was no evidence which interventions could reduce the risk of recurrence or of future cardiovascular disease in this population of women, they made a research recommendation.

Cost effectiveness and resource use

No relevant studies were identified in a systematic review of the economic evidence.

At present there is considerable variation in practice regarding follow-up for women who have had hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. In areas where little support is provided, some follow up will be needed in order to provide this information, which may lead to an increase in resource use. Nonetheless, providing information about the longer term risks of cardiovascular disease gives the opportunity for women to take steps to reduce this risk throughout their lifetime. This will result in increased benefits for women and a reduction in the debilitating consequences of cardiovascular disease, and the financial implications of managing long-term cardiovascular disease for the NHS.

Other factors the committee took into account

The committee also noted that there is uncertainty with regard to the length of time that women who have had a hypertensive disorder in pregnancy should be followed up. They recognised that the length of the surveillance period is not well-established and that the consequences of late intervention can be severe, including increased morbidity, mortality, resource use, and limited therapeutic options. The committee agreed that a lack of clarity as to whom should be conducting follow-up contributes to this problem, and women report that there is uncertainty as to what to do in case they feel unwell, or who to consult. Based on their expertise the committee therefore made a recommendation that women with severe or recurrent hypertension who had had a preterm birth should be offered offered pre-pregnancy counselling to discuss the risks that may be present in a future pregnancy.

References

AMSTAR checklist

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017 Sep 21; 358:j4008. [PMC free article: PMC5833365] [PubMed: 28935701]Auger 2017

Auger, Nathalie, Fraser, William D., Schnitzer, Mireille, Leduc, Line, Healy-Profitos, Jessica, Paradis, Gilles, Recurrent pre-eclampsia and subsequent cardiovascular risk, Heart (British Cardiac Society), 103, 235–243, 2017 [PubMed: 27530133]Bellamy 2007

Bellamy, L., Casas, J. P., Hingorani, A. D., Williams, D. J., Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: Systematic review and meta-analysis, British Medical Journal, 335, 974–977, 2007 [PMC free article: PMC2072042] [PubMed: 17975258]Benschop 2018

Benschop, Laura, Duvekot, Johannes J., Versmissen, Jorie, van Broekhoven, Valeska, Steegers, Eric A. P., Roeters van Lennep, Jeanine E., Blood Pressure Profile 1 Year After Severe Preeclampsia, Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979), 71, 491–498, 2018 [PubMed: 29437895]Black 2016

Black, Mary Helen, Zhou, Hui, Sacks, David A., Dublin, Sascha, Lawrence, Jean M., Harrison, Teresa N., Reynolds, Kristi, Hypertensive disorders first identified in pregnancy increase risk for incident prehypertension and hypertension in the year after delivery, Journal of Hypertension, 34, 728–35, 2016 [PubMed: 26809018]Boghossian 2015

Boghossian, Nansi S., Albert, Paul S., Mendola, Pauline, Grantz, Katherine L., Yeung, Edwina, Delivery Blood Pressure and Other First Pregnancy Risk Factors in Relation to Hypertensive Disorders in Second Pregnancies, American Journal of Hypertension, 28, 1172–9, 2015 [PMC free article: PMC4542849] [PubMed: 25673041]Bokslag 2017

Bokslag, Anouk, Teunissen, Pim W., Franssen, Constantijn, van Kesteren, Floortje, Kamp, Otto, Ganzevoort, Wessel, Paulus, Walter J., de Groot, Christianne J. M., Effect of early-onset pre-eclampsia on cardiovascular risk in the fifth decade of life, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 216, 523.e1–523.e7, 2017 [PubMed: 28209494]Bramham 2011

Bramham, Kate, Briley, Annette L., Seed, Paul, Poston, Lucilla, Shennan, Andrew H., Chappell, Lucy C., Adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in women with previous pre-eclampsia: a prospective study, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 204, 512.e1–9, 2011 [PMC free article: PMC3121955] [PubMed: 21457915]Callaway 2013

Callaway, L. K., Mamun, A., McIntyre, H. D., Williams, G. M., Najman, J. M., Nitert, M. D., Lawlor, D. A., Does a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy help predict future essential hypertension? Findings from a prospective pregnancy cohort study, Journal of Human Hypertension, 27, 309–14, 2013 [PubMed: 23223085]Canoy 2016

Canoy, D., Cairns, B. J., Balkwill, A., Wright, F. L., Khalil, A., Beral, V., Green, J., Reeves, G., Hypertension in pregnancy and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: A prospective study in a large UK cohort, International Journal of Cardiology, 222, 1012–1018, 2016 [PMC free article: PMC5047033] [PubMed: 27529390]Drost 2012

Drost, Jose T., Arpaci, Ganiye, Ottervanger, Jan Paul, de Boer, Menko Jan, van Eyck, Jim, van der Schouw, Yvonne T., Maas, Angela H. E. M., Cardiovascular risk factors in women 10 years post early pre-eclampsia: the Preeclampsia Risk EValuation in FEMales study (PREVFEM), European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 19, 1138–44, 2012 [PubMed: 21859777]Ebbing 2017

Ebbing, Cathrine, Rasmussen, Svein, Skjaerven, Rolv, Irgens, Lorentz M., Risk factors for recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, a population-based cohort study, Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 96, 243–250, 2017 [PubMed: 27874979]Ehrenthal 2015

Ehrenthal, Deborah B., Rogers, Stephanie, Goldstein, Neal D., Edwards, David G., Weintraub, William S., Cardiovascular risk factors one year after a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, Journal of women’s health (2002), 24, 23–9, 2015 [PMC free article: PMC4302950] [PubMed: 25247261]Grandi 2017

Grandi, S. M., Vallee-Pouliot, K., Reynier, P., Eberg, M., Platt, R. W., Arel, R., Basso, O., Filion, K. B., Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy and the Risk of Subsequent Cardiovascular Disease, Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 31, 412–421, 2017 [PubMed: 28816365]Hermes 2013

Hermes, W, Franx, A, Pampus, Mg, Bloemenkamp, Kw, Bots, Ml, Post, Ja, Porath, M, Ponjee, Ga, Tamsma, Jt, Mol, Bw, Groot, Cj, Cardiovascular risk factors in women who had hypertensive disorders late in pregnancy: a cohort study, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 208, 474.e1–8, 2013 [PubMed: 23399350]QUIPS checklist

Hayden, J. A., Bombardier, CEvaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Annals of internal medicine 144.6 (2006): 427–437. [PubMed: 16549855]- Hayden, J. A., van der Windt, D. A., Cartwright, J. L., Côté, P., Bombardier, C.Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Annals of internal medicine 158.4 (2013): 280–286. [PubMed: 23420236]

Li 2014

Li, X. L., Chen, T. T., Dong, X., Gou, W. L., Lau, S., Stone, P., Chen, Q., Early onset pre-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancies correlates with early onset pre-eclampsia in first pregnancy, European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, & Reproductive Biology, 177, 94–9, 2014 [PubMed: 24784713]Mahande 2013

Mahande, Michael J., Daltveit, Anne K., Mmbaga, Blandina T., Masenga, Gileard, Obure, Joseph, Manongi, Rachel, Lie, Rolv T., Recurrence of pre-eclampsia in northern Tanzania: a registry-based cohort study, PLoS ONE, 8, e79116, 2013 [PMC free article: PMC3815128] [PubMed: 24223889]Mannisto 2013

Mannisto, T., Mendola, P., Vaarasmaki, M., Jarvelin, M. R., Hartikainen, A. L., Pouta, A., Suvanto, E., Elevated blood pressure in pregnancy and subsequent chronic disease risk, Circulation, 127, 681–90, 2013 [PMC free article: PMC4151554] [PubMed: 23401113]McDonald 2008

McDonald, Sarah D., Malinowski, Ann, Zhou, Qi, Yusuf, Salim, Devereaux, Philip J., Cardiovascular sequelae of pre-eclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses, American Heart Journal, 156, 918–30, 2008 [PubMed: 19061708]McDonald 2013

McDonald, Sarah D., Ray, Joel, Teo, Koon, Jung, Hyejung, Salehian, Omid, Yusuf, Salim, Lonn, Eva, Measures of cardiovascular risk and subclinical atherosclerosis in a cohort of women with a remote history of pre-eclampsia, Atherosclerosis, 229, 234–9, 2013 [PubMed: 23664201]Melamed 2012

Melamed, Nir, Hadar, Eran, Peled, Yoav, Hod, Moshe, Wiznitzer, Arnon, Yogev, Yariv, Risk for recurrence of pre-eclampsia and outcome of subsequent pregnancy in women with pre-eclampsia in their first pregnancy, The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians, 25, 2248–51, 2012 [PubMed: 22524456]Mito 2018

Mito, Asako, Arata, Naoko, Qiu, Dongmei, Sakamoto, Naoko, Murashima, Atsuko, Ichihara, Atsuhiro, Matsuoka, Ryu, Sekizawa, Akihiko, Ohya, Yukihiro, Kitagawa, Michihiro, Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a strong risk factor for subsequent hypertension 5 years after delivery, Hypertension research : official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension, 41, 141–146, 2018 [PubMed: 29093561]Mongraw-Chaffin 2010

Mongraw-Chaffin, Morgana L., Cirillo, Piera M., Cohn, Barbara A., Preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease death: prospective evidence from the child health and development studies cohort, Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979), 56, 166–71, 2010 [PMC free article: PMC3037281] [PubMed: 20516394]Nzelu 2017

Nzelu, Diane, Dumitrascu-Biris, Dan, Hunt, Katharine F., Cordina, Mark, Kametas, Nikos A., Pregnancy outcomes in women with previous gestational hypertension: A cohort study to guide counselling and management, Pregnancy Hypertension, 2017 [PubMed: 29113718]Scholten 2013

Scholten, R. R., Hopman, M. T. E., Sweep, F. C. G. J., Vlugt, M. J. V. D., Dijk, A. P. V., Oyen, W. J., Lotgering, F. K., Spaanderman, M. E. A., Co-occurrence of cardiovascular and prothrombotic risk factors in women with a history of pre-eclampsia, Obstetrics and Gynecology, 121, 97–105, 2013 [PubMed: 23262933]Tooher 2013

Tooher, J., Chiu, C. L., Yeung, K., Lupton, S. J., Thornton, C., Makris, A., O’Loughlin, A., Hennessy, A., Lind, J. M., High blood pressure during pregnancy is associated with future cardiovascular disease: An observational cohort study, BMJ Open, 3, e002964, 2013 [PMC free article: PMC3731716] [PubMed: 23883883]Tooher 2016

Tooher, Jane, Thornton, Charlene, Makris, Angela, Ogle, Robert, Korda, Andrew, Horvath, John, Hennessy, Annemarie, Hypertension in pregnancy and long-term cardiovascular mortality: a retrospective cohort study, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 214, 722.e1–6, 2016 [PubMed: 26739795]Tooher 2017

Tooher, Jane, Thornton, Charlene, Makris, Angela, Ogle, Robert, Korda, Andrew, Hennessy, Annemarie, All Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy Increase the Risk of Future Cardiovascular Disease, Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979), 70, 798–803, 2017 [PubMed: 28893895]van Oostwaard 2015

van Oostwaard, Miriam F., Langenveld, Josje, Schuit, Ewoud, Papatsonis, Dimitri N. M., Brown, Mark A., Byaruhanga, Romano N., Bhattacharya, Sohinee, Campbell, Doris M., Chappell, Lucy C., Chiaffarino, Francesca, Crippa, Isabella, Facchinetti, Fabio, Ferrazzani, Sergio, Ferrazzi, Enrico, Figueiro-Filho, Ernesto A., Gaugler-Senden, Ingrid P. M., Haavaldsen, Camilla, Lykke, Jacob A., Mbah, Alfred K., Oliveira, Vanessa M., Poston, Lucilla, Redman, Christopher W. G., Salim, Raed, Thilaganathan, Baskaran, Vergani, Patrizia, Zhang, Jun, Steegers, Eric A. P., Mol, Ben Willem J., Ganzevoort, Wessel, Recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: an individual patient data metaanalysis, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 212, 624.e1–17, 2015 [PubMed: 25582098]Wu 2017

Wu, Pensee, Haththotuwa, Randula, Kwok, Chun Shing, Babu, Aswin, Kotronias, Rafail A., Rushton, Claire, Zaman, Azfar, Fryer, Anthony A., Kadam, Umesh, Chew-Graham, Carolyn A., Mamas, Mamas A., Preeclampsia and Future Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes, 10, 2017 [PubMed: 28228456]Yeh 2014

Yeh, J. S., Cheng, H. M., Hsu, P. F., Sung, S. H., Liu, W. L., Fang, H. L., Chuang, S. Y., Synergistic effect of gestational hypertension and postpartum incident hypertension on cardiovascular health: A nationwide population study, European Heart Journal, 35, 368, 2014 [PMC free article: PMC4338688] [PubMed: 25389282]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocol

Appendix B. Literature search strategies

Review question search strategies

Databases: Medline; Medline EPub Ahead of Print; and Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

Databases: Embase; and Embase Classic

Databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; and Health Technology Assessment

Health economics search strategies

Databases: Medline; Medline EPub Ahead of Print; and Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

Databases: Embase; and Embase Classic

Database: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

Databases: Health Technology Assessment; and NHS Economic Evaluation Database

Appendex D. Clinical evidence tables

Table 5. Clinical evidence tables (PDF, 1.4M)

Appendix E. Forest plots

Not applicable to this review question.

Appendix F. Quality assessment of the included studies

Long-term outcomes at any future date

Table 6. Long-term outcomes in women with hypertensive disorders at index pregnancy

Table 7. Long-term outcomes in women with pre-eclampsia at index pregnancy

Table 8. Long-term outcomes in women with gestational hypertension at index pregnancy

Table 9. Long-term outcomes in women with chronic hypertension at index pregnancy

Recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Table 10Recurrence of HDP at subsequent pregnancies in women with hypertensive disorders at index pregnancy

| Study | Study design | Checklist and overall quality assessment | Follow-up time | Prevalence in women with any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy | Prevalence in control group | Relative effect size (95% CI) | Subsequent pregnancy/ any future pregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence of pre-eclampsia in future pregnancies; timing of delivery not specified | |||||||

| Nzelu 20181,2 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS High | Not reported (study length was 5 years) | 97/773 (12.54%) | - | - | Any future pregnancy |

| van Oostwaard 20153 | IPD MA |

AMSTAR High | Not reported | 13725/99208 (13.8%) [95% CI 13.6%-14.1%] | - | - | Unclear |

| Occurrence of gestational hypertension; timing of delivery not specified | |||||||

| Nzelu 20181,2 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS High | Not reported (study length was 5 years) | 173/773 (22.4%) | - | - | Any future pregnancy |

| van Oostwaard 20153 | IPD MA |

AMSTAR High | Not reported | 6797/79169 (8.6%) [95% CI8.4%-8.8%] | - | - | Unclear |

| Occurrence of any HDP; timing of delivery not specified | |||||||

| Nzelu 20181,2 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS High | Not reported (study length was 5 years) | 270/773 (35%) | - | - | Any future pregnancy |

| van Oostwaard 20153 | IPD MA |

AMSTAR High | Not reported | 20545/99415 (20.7%) [95% CI 20.4%-20.9%] | - | - | Unclear |

CI confidence interval; HDP hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; IPD individual patient data; MA meta-analysis; QUIPS Quality in Prognosis Studies

| Study | Study design | Quality assessment | Follow-up time | Prevalence in women with pre-eclampsia | Prevalence in control group | Relative effect size (95% CI) | Subsequent pregnancy/ any future pregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence of pre-eclampsia; timing of delivery not specified | |||||||

| Boghossian 20151 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 8 years) | 150/1319 (11.4%) | 253/23913 (1.1%) | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Li 20142 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 4 years) | 55/92 (59.8%) | - | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Melamed 2012 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS High | Not reported (study length was 12 years) | 17/289 (5.9%) | 7/896 (0.8%) | Subsequent pregnancy | |

| van Oostwaard 20153 | IPD MA |

AMSTAR High | Not reported | 16% (actual number not reported) | - | - | Unclear |

| Recurrence of pre-eclampsia; delivery > 37 weeks | |||||||

| Ebbing 2016 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 45 years) | 3229/25105 (12.86%) | - | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Mahande 20134 | Prospective cohort |

QUIPS High | Median 6.5 years | 42/171 (24.6%) | - | RR 9.2 (6.4 to 13.2) | Any future pregnancy |

| Recurrence of pre-eclampsia; delivery 34-36+6 weeks | |||||||

| Bramham 2011 | Prospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 2 years) | 47/196 (23.97%) | - | - | Any future pregnancy |

| Ebbing 2016 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 45 years) | 891/3877 (22.98%) | - | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Recurrence of pre-eclampsia; delivery 28-33+6 weeks | |||||||

| Bramham 2011 | Prospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 2 years) | 106/304 (34.86%) | - | - | Any future pregnancy |

| Ebbing 2016 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 45 years) | 474/1441 (32.89%) | - | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Occurrence of gestational hypertension; timing of delivery not specified | |||||||

| Boghossian 20151 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 8 years) | 156/1319 (11.82%) | 284/23913 (1.2%) | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| van Oostwaard 20153 | IPD MA |

AMSTAR High | Not reported | 6% (actual number not reported) | - | - | Unclear |

| Occurrence of gestational hypertension; delivery > 37 weeks in index pregnancy | |||||||

| Ebbing 2016 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 45 years) | 1569/25105 (6.24%) | - | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Occurrence of gestational hypertension; delivery 34-36+6 weeks in index pregnancy | |||||||

| Bramham 2011 | Prospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 2 years) | 85/196 (43.36%) | - | - | Any future pregnancy |

| Ebbing 2017 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 45 years) | 287/3877 (7.4%) | - | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Occurrence of gestational hypertension; delivery 28-33+6 weeks in index pregnancy | |||||||

| Bramham 2011 | Prospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 2 years) | 162/304 (53.28%) | - | - | Any future pregnancy |

| Ebbing 2017 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 45 years) | 94/1441 (6.52%) | - | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Occurrence of chronic hypertension; timing of delivery not specified | |||||||

| Boghossian 2015 | Retrospective cohort |

QUIPS Moderate | Not reported (study length was 8 years) | 25/1319 (1.9%) | 57/23913 (0.24%) | - | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Occurrence of any HDP; timing of delivery not specified | |||||||

| van Oostwaard 20153 | IPD MA |

AMSTAR High | Not reported | 20.4% (actual number not reported) | - | - | Unclear |

- 1

Women with chronic hypertension were excluded

- 2

Factors adjusted for: maternal age, BMI, MAP, gestational age of previous hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, and number of previous pregnancies with hypertensive disorders

- 3

Case-control studies reporting on recurrence were included

Table 11. Recurrence of HDP at subsequent pregnancies in women with pre-eclampsia at index pregnancy

Appendix H. Economic evidence tables

No economic evidence was identified for this review question.

Appendix I. Health economic evidence profiles

No economic evidence was identified for this review question.

Appendix J. Health economic analysis

No health economic analysis was conducted for this review question.

Appendix K. Excluded studies

Clinical studies

Table 14. Clinical excluded studies with reasons for exclusion

Economic studies

Table 15. Economic excluded studies with reasons for exclusion

Appendix L. Research recommendations

1. In women who have had hypertension during pregnancy, what interventions reduce the risk of a) recurrent hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and b) subsequent cardiovascular disease?

Why this is important

There is increasing evidence that highlights the increased risk of recurrent hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in women with chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia in an index pregnancy. These women also have an increased risk of longer term cardiovascular disease. Recent NICE guidelines have enumerated the magnitude of the risk, but not provided recommendations on how this risk is best reduced. Interventions shown to be beneficial in the general adult population may not be automatically extrapolated for postnatal women due to considerations around the difference in age and sex of those studied, the need to demonstrate safety of pharmacological interventions for breastfeeding women, and the well-documented challenges of competing demands during the postnatal period.

FINAL

Evidence review

These evidence reviews were developed by The National Guideline Alliance hosted by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian.

Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties.

NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government, Scottish Government, and Northern Ireland Executive. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn.

- Review Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Risk of Future Cardiovascular Disease in Women.[Nurs Womens Health. 2020]Review Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Risk of Future Cardiovascular Disease in Women.Vahedi FA, Gholizadeh L, Heydari M. Nurs Womens Health. 2020 Apr; 24(2):91-100. Epub 2020 Feb 28.

- Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy - A Life-Long Risk?![Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2013]Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy - A Life-Long Risk?!Schausberger CE, Jacobs VR, Bogner G, Wolfrum-Ristau P, Fischer T. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2013 Jan; 73(1):47-52.

- Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and subsequently measured cardiovascular risk factors.[Obstet Gynecol. 2009]Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and subsequently measured cardiovascular risk factors.Magnussen EB, Vatten LJ, Smith GD, Romundstad PR. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov; 114(5):961-970.

- Postpartum counseling in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.[Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021]Postpartum counseling in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.Triebwasser JE, Janssen MK, Sehdev HM. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021 Jan; 3(1):100285.

- Review Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Subsequent Cardiovascular Disease: Current National and International Guidelines and the Need for Future Research.[Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019]Review Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Subsequent Cardiovascular Disease: Current National and International Guidelines and the Need for Future Research.Gamble DT, Brikinns B, Myint PK, Bhattacharya S. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019; 6:55. Epub 2019 May 17.

- Evidence review for advice at dischargeEvidence review for advice at discharge

- Panicum repens isolate OSBAR 000641 maturase K (matK) gene, partial cds; chlorop...Panicum repens isolate OSBAR 000641 maturase K (matK) gene, partial cds; chloroplastgi|1586082187|gb|MH552126.1|Nucleotide

- Panicum repens voucher FLAS:Majure 5039 ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/ox...Panicum repens voucher FLAS:Majure 5039 ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (rbcL) gene, partial cds; chloroplastgi|1338006284|gb|KY627152.1|Nucleotide

- Profile neighbors for GEO Profiles (Select 55748567) (199)GEO Profiles

- Profile neighbors for GEO Profiles (Select 55745525) (199)GEO Profiles

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...