Introduction

This chapter presents vignettes of counseling/intervention sessions between various service professionals and either 1) women of childbearing age where FASD prevention is warranted, and/or 2) individuals who have or may have an FASD or their family members. The vignettes are intended to provide real-world examples and overviews of approaches best suited (and not suited to) FASD prevention and intervention.

The Culturally Competent Counselor

This TIP, like all others in the TIP series, recognizes the importance of delivering culturally competent care. Cultural competency, as defined by HHS, is…

“A set of values, behaviors, attitudes, and practices within a system, organization, program, or among individuals that enables people to work effectively across cultures. It refers to the ability to honor and respect the beliefs, language, interpersonal styles, and behaviors of individuals and families receiving services, as well as staff who are providing such services. Cultural competence is a dynamic, ongoing, developmental process that requires a long-term commitment and is achieved over time” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003, p. 12).

A critical element of this definition is the connection between attitude and behavior, as shown in the table on the next page.

Areas of Clinical Focus

In this chapter, you are invited to consider different methods and approaches to practicing prevention of an AEP and/or interventions and modifications for individuals who have or may have an FASD. The ten scenarios are common situations for behavioral health professionals and focus on:

- Intervention with a woman of childbearing age who has depression, is consuming alcohol, and may become pregnant (AEP Prevention)

- Examining alcohol history with a woman of childbearing age in substance abuse treatment for a drug other than alcohol (AEP Prevention)

- Intervention with a woman who is pregnant (AEP Prevention)

- Intervention with a woman who is pregnant and consuming alcohol, and who is exhibiting certain triggers for alcohol consumption, including her partner (AEP Prevention)

- Interviewing a client for the possible presence of an FASD (FASD Intervention)

- Interviewing a birth mother about a son who may have an FASD and is having trouble in school (FASD Intervention)

- Reviewing an FASD diagnostic report with the family (FASD Intervention)

- Making modifications to treatment for an individual with an FASD (FASD Intervention)

- Working with an adoptive parent to create a safety plan for an adult male with an FASD who is seeking living independence (FASD Intervention)

- Working with a birth mother to develop strategies for communicating with a school about an Individualized Education Plan for her daughter, who has an FASD (FASD Intervention)

Table

Acknowledging and validating the client's opinions and worldview Approaching the client as a partner in treatment

Clinical Vignettes

Organization of the Vignettes

To better organize the learning experience, each vignette contains an Overview of the general learning intent of the vignette, Background on the client and the setting, Learning Objectives, and Master Clinician Notes from an “experienced counselor or supervisor” about the strategies used, possible alternative techniques, timing of interventions, and areas for improvement. The Master Clinician is meant to represent the combined experience and expertise of the TIP's consensus panel members, providing insights into each case and suggesting possible approaches. It should be kept in mind, however, that some techniques suggested in these vignettes may not be appropriate for use by all clinicians, depending on that professional's level of training, certification, and licensure. It is the responsibility of the counselor to determine what services he or she can legally/ethically provide.

1. INTERVENTION WITH A WOMAN OF CHILDBEARING AGE WHO HAS DEPRESSION, IS CONSUMING ALCOHOL, AND MAY BECOME PREGANT (AEP PREVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates how and why a counselor would address prevention of an AEP with a young woman who is being seen for depression.

Background: This vignette takes place in a college counseling center where Serena, 20, is receiving outpatient services for the depression that she's been feeling for about 4 months. In her intake interview, Serena has indicated that she consumes alcohol, is not pregnant, and is sexually active. She has had two prior sessions with the counselor, during which they have discussed Serena's general background, family interactions, social supports, and her outlook on school.

In today's session, they have been discussing her boyfriend, Rob. A therapeutic relationship has begun to form between Serena and the counselor, and the counselor would now like to explore Serena's alcohol use and whether it is a possible contributing factor in her depression. While doing this, the counselor will identify an opportunity to deliver an informal selective intervention to prevent a possible AEP.

Learning Objectives

- To illustrate that clients often have multiple issues that need to be addressed besides their primary reason for seeking counseling.

- To demonstrate a selective intervention (“FLO”) for preventing an alcohol-exposed unplanned pregnancy.

- To recognize that prevention of an AEP can be accomplished by eliminating alcohol use during pregnancy or preventing a pregnancy during alcohol use; often the most effective route is to prevent the pregnancy.

2. EXAMINING THE ALCOHOL HISTORY WITH A WOMAN OF CHILDBEARING AGE IN SUBSTANCE ABUSE TREATMENT FOR A DRUG OTHER THAN ALCOHOL (AEP PREVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates the value of asking about alcohol use in a female substance abuse treatment client of childbearing age, even though her primary drug is not alcohol.

Background: Chloe is being seen at an outpatient treatment center for methamphetamine abuse. The counselor has the health history that was provided during intake. It indicates that Chloe reports as non-pregnant, but is 28 (of childbearing age) and is sexually active.

The counselor wants to explore whether Chloe is using other substances, as well as screening for a possible mental health problem. Given that the client is sexually active, there is a risk of an unplanned pregnancy, therefore the counselor begins with alcohol.

Learning Objectives

- To emphasize the importance of probing for alcohol use even if it is not the primary drug.

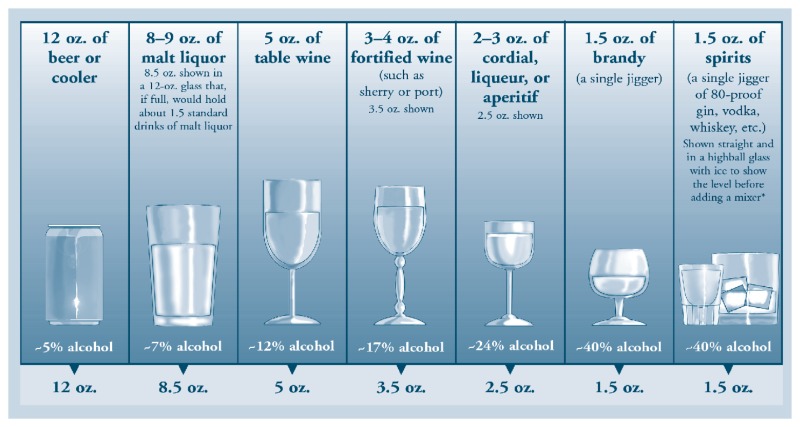

- To recognize that quantity of use is subjective. The use of a visual helps the client understand what a one-drink equivalent is.

- To recognize that if a mental health issue presents itself, it will need to be addressed concurrently.

3. INTERVENTION WITH A WOMAN WHO IS PREGNANT (AEP PREVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates that screening for alcohol use should be done at every visit with women who are—or are at an indicated likelihood for becoming—pregnant. Alcohol-exposed pregnancies occur in all demographics, regardless of socio-economic status, age, ethnicity, or marital status.

Background: April, 27, works full-time. She recently found out she is pregnant with her first child. She and her husband have relocated to a new city, and she is being seen at a private OBGYN office for the first time.

Learning Objectives

- To recognize that asking about alcohol use during the first visit only is not enough; screening should occur at every visit.

- To identify that a woman could begin drinking during the pregnancy if she is experiencing a relapse.

- To highlight there is no known safe amount of alcohol use during pregnancy.

4. INTERVENTION WITH A WOMAN WHO IS PREGNANT AND CONSUMING ALCOHOL, AND WHO IS EXHIBITING CERTAIN TRIGGERS FOR ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION, INCLUDING HER PARTNER (AEP PREVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates a method for obtaining the alcohol history of a pregnant woman.

Background: Isabel, 30, has been referred to an outpatient mental health treatment center for feelings of depression. She is Hispanic, married, and pregnant (in her third trimester), and has one other child. The counselor and client have completed the intake process and Isabel has participated in the development of her comprehensive treatment plan. This is their third meeting. The counselor and Isabel agreed at the end of their last session that this would be about potential health risks with the pregnancy.

Learning Objectives

- To learn how to use a practical visual tool (a calendar) to more accurately and effectively identify client drinking patterns and possible triggers for alcohol consumption.

- To identify verbal cues that can indicate that a topic is becoming uncomfortable for a client, and apply effective techniques when a client becomes upset.

5. INTERVIEWING A CLIENT FOR THE POSSIBLE PRESENCE OF AN FASD (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates the clues the health care worker is receiving that suggest an impairment and possible FASD. A client with an FASD, with brain damage, will not receive the information from the worker the same way someone without FASD will receive it. The client may not have a diagnosis and may not immediately present as someone with a disability. There are a number of questions the worker could ask to determine whether they need to operate in a different kind of therapeutic environment with the client. The main goal of this vignette is for the health care worker to consider the possibility of an FASD, not to diagnose an FASD, which can only be done by qualified professionals. A woman who has an FASD is at high risk for having a child with an FASD.

Background: Marta is a single woman, 19, who recently had a baby, and is being seen at a Healthy Start center by a health care worker. This is the first time they are meeting. The health care worker's colleague asked her to meet with Marta as she knew that the health care worker was knowledgeable about FASD and was known as the office “FASD champion.” The colleague has begun to suspect that Marta may need an evaluation for FASD, as she has repeatedly missed appointments or been late, gotten lost on the way to the center, failed to follow instructions, spoken at inappropriate times, and has repeated foster placement and criminal justice involvement in her case history. The only information in the history about Marta's biological mother is that she is dead. The colleague wants the health care worker to conduct an informal interview to assess the possibility of an FASD.

Learning Objectives

- To learn how to identify behavioral and verbal cues in conversation with a client that may indicate that the client has an FASD.

- To learn how to apply knowledge of FASD and its related behavioral problems, in order to reassess clients with troublesome behaviors or concerns for factors other than knowing noncompliance.

6. INTERVIEWING A BIRTH MOTHER ABOUT A SON WHO MAY HAVE AN FASD AND IS HAVING TROUBLE IN SCHOOL (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: Counseling professionals in mental health or substance abuse treatment may avoid talking to a female client or family member about their alcohol use during pregnancy, either to avoid communicating any shame or judgment to that individual, or out of a lack of knowledge about FASD. This case illustrates a scenario where such a discussion may prove fruitful, and the sensitivity required when starting the discussion.

Background: The vignette begins with a community mental health professional talking to Dixie Wagner, 35, about the behavior of Dixie's 7-year-old biological son, Jarrod. (Jarrod is not present at this session.) Jarrod is in trouble again for hitting another child, and this is causing distress for the mother that the mental health professional wants to address, which leads into a discussion of FASD.

Learning Objectives

- Cite methods to help the caregiver clarify the child's issues and discover why the child is having problems.

- Specify skills needed to follow the caregiver's lead in asking probing questions.

- Explore the negative perceptions surrounding prenatal alcohol exposure, and examine how lack of knowledge or fear of shaming may interfere with asking the right questions.

7. REVIEWING AN FASD DIAGNOSTIC REPORT WITH THE FAMILY (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: The purpose of this vignette is to provide counselors with guidance on how to review a diagnostic report (or Medical Summary Report) with family members of a child who has been just diagnosed with FAS.

Background: The client, Jenine, is the caregiver of her grandson, Brice. Jenine is meeting with a counselor from the Indian Health Service to review Brice's Medical Summary Report for the first time. In a prior session, Jenine confided that she felt overwhelmed. Knowing how detailed a Medical Summary Report can be, the counselor suggested that Jenine bring trusted family members and elders to this session. Together they arranged for Jenine's sister, aunt, and an elder to attend.

Learning Objectives

- To recognize that clients will need support after an FASD-related diagnosis.

- To identify how to help the client prioritize the child's and the caregiver's needs.

- To recognize that the client will need to be educated to understand that the child's behavior problems are due to damage to brain caused by prenatal alcohol exposure.

8. MAKING MODIFICATIONS TO TREATMENT FOR AN INDIVIDUAL WITH AN FASD (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: The purpose of this vignette is to demonstrate how to modify treatment plans for a client with an FASD.

Background: The client, Yvonne, is an adolescent female with a history of truancy and fighting. She has been mandated to counseling for anger management, and has missed her last two appointments. When the counselor phoned her about the missed appointment, Yvonne's mother suggested that Yvonne may not be taking her medication, and hinted that Yvonne may be depressed.

Learning Objectives

- To adjust expectations regarding age-appropriate behavior, since individuals with an FASD may be adult-aged by calendar years, but are much younger developmentally and cognitively.

- To demonstrate the value of collateral information and how to ask an individual for consent.

- To demonstrate the importance of seeking involvement from parents and caregivers.

- To identify how concrete thinking plays a role in comprehension for clients with an FASD.

- To cite the value of time spent developing rapport and establishing trust.

9. WORKING WITH AN ADOPTIVE PARENT TO CREATE A SAFETY PLAN FOR AN ADULT MALE WITH AN FASD WHO IS SEEKING LIVING INDEPENDENCE (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: The purpose of this vignette is to demonstrate how counselors can help develop a safety plan for clients with an FASD. This vignette focuses on creating a safety plan with a caregiver, as many individuals with FASD have someone in their life who provides advocacy and support. If there is no such person in the life of the client with FASD, an important treatment goal will be to identify persons who can fill that role.

Background: In this vignette, Mike's son, Desmond, is 21 years old, and has been diagnosed with an FASD. Mike adopted Desmond when he was five years old. Since Desmond turned 16, and Mike's wife left him (partly due to the difficulties of parenting Desmond), Mike has been Desmond's sole caregiver. Lately, Mike has become increasingly distressed about his son and life in general, and has sought counseling from a mental health provider.

We are picking up this session after Mike has mentioned that Desmond is excitedly preparing to live on his own, with the move-in date just a month away. Mike is sure his son can't handle all the responsibilities of independent living. He has tried to talk to Desmond about this, his son doesn't seem to listen or agree. Mike is realizing that there is a lot he has not talked about with his son.

The counselor took time to gather a good deal of background information. Mike is here on his own in this visit, but the counselor has met Desmond. Desmond has intellectual abilities in what is called the borderline range (just below average). Like many individuals with an FASD, he acts like someone who is younger. In the first session, when the counselor asked Mike to estimate Desmond's “acts-like” (i.e., functional) age, Mike said that Desmond still acts like someone who might be in 10th grade. As the counselor has gotten to know Desmond, this estimate seems accurate. The counselor has also carefully reviewed Desmond's Medical Summary Report (from age 11) and his latest school testing (age 20, when he graduated from high school). She now better understands his unique learning profile.

Mike also told the counselor that Desmond was diagnosed with ADHD at age 8, which helped with an accommodations plan at school and a medication regimen. When Mike tried to transfer responsibility for taking the medication to Desmond 3 years ago, he couldn't remember to take it on his own. When Mike and Desmond's doctor realized Desmond showed no decline in function off the medications, they decided to stop the regimen. Without a clear benefit, and because Desmond could be pressured to give away his stimulants to peers, stopping the medication seemed wise.

Learning Objectives

- To show how to identify and validate caregiver concerns, and how to integrate common issues for individuals with FASD in safety planning.

- To show that safety for a client with an FASD requires a plan that decreases risk, increases protective factors, and focuses on comprehensive life skills planning.

- To illustrate how to assist caregivers as they proactively develop strategies to ensure their child's safety.

- To demonstrate that individuals with FASD need a plan that is practical, useful, developmentally appropriate, uses concrete language and visual aids, uses role-play, and takes into account their unique cognitive/learning and behavioral profile.

10. WORKING WITH A BIRTH MOTHER TO DEVELOP STRATEGIES FOR COMMUNICATING WITH A SCHOOL ABOUT AN INDIVIDUALIZED EDUCATION PLAN FOR HER DAUGHTER WHO HAS AN FASD (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates how a social worker can make useful suggestions for a parent or caregiver's first meeting with educators at the beginning a new school year.

Background: The start of the school year is 2 weeks away. Denise is a birth mother who is meeting with a social worker to get some advice on how to educate the school staff about working with her daughter, Elise, who is 11. Elise has recently been identified as having an FASD, although she has been tested as having a “normal” IQ and is in a mainstream learning setting. This social worker was part of the diagnostic team that assessed Elise for FASD, but this is her first time helping with Elise's school issues. Denise is hoping to develop learning strategies that she can discuss with the school staff in an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meeting.

Learning Objectives

- To describe typical challenges that children with an FASD may face in the classroom.

- To demonstrate how collaboration and creativity can lead to accommodations that result in improved outcomes for a child with an FASD.

Publication Details

Copyright

Publisher

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), Rockville (MD)

NLM Citation

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (US). Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD). Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 58.) Chapter 3, Clinical Vignettes.