Background

WHO estimates that in 2015, 71 million persons were living with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection worldwide and that 399 000 died from cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma caused by HCV infection. In May 2016, the World Health Assembly endorsed the Global Health Sector Strategy (GHSS) on viral hepatitis, which proposes to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030 (90% reduction in incidence and 65% reduction in mortality). Elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat requires 90% of those infected to be diagnosed and 80% of those diagnosed to be treated.

Rationale

Since the last update to the Guidelines was issued in 2016, three key developments have prompted changes in terms of when to treat and what treatments to use. First, the use of safe and highly effective direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens for all persons improves the balance of benefits and harms of treating persons with little or no fibrosis, supporting a strategy of treating all persons with chronic HCV infection, rather than reserving treatment for persons with more advanced disease. Second, since 2016, several new, pangenotypic DAA medicines have been approved by at least one stringent regulatory authority, reducing the need for genotyping to guide treatment decisions. Third, the continued substantial reduction in the price of DAAs has enabled treatment to be rolled out rapidly in a number of low- and middle-income countries.

Scope

These guidelines aim to provide evidence-based recommendations on the care and treatment of persons diagnosed with chronic HCV infection. They update the care and treatment section of the WHO Guidelines for the screening, care and treatment of persons with hepatitis C infection issued in April 2016. The 2017 Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing update the screening section.

Audience

These guidelines are intended for government officials to use as the basis for developing national hepatitis policies, plans and treatment guidelines. These include country programme managers and health-care providers responsible for planning and implementing hepatitis care and treatment programmes, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

WHO developed these guidelines in accordance with procedures established by its Guidelines Review Committee. Systematic reviews were undertaken to assess the safety and efficacy of treatment regimens in adults, to examine the morbidity and mortality from extrahepatic manifestations in persons with HCV infection and to review the literature on cost–effectiveness. In addition, modelling was carried out. A regionally representative and multidisciplinary Guidelines Development Group met in September 2017 to formulate the recommendations, using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach. This included an assessment of the quality of evidence (high, moderate, low or very low), consideration of the overall balance of benefits and harms (at individual and population levels), patient/health worker values and preferences, resource use, cost–effectiveness, and consideration of feasibility and effectiveness across a variety of resource-limited settings.

Summary of the new recommendations

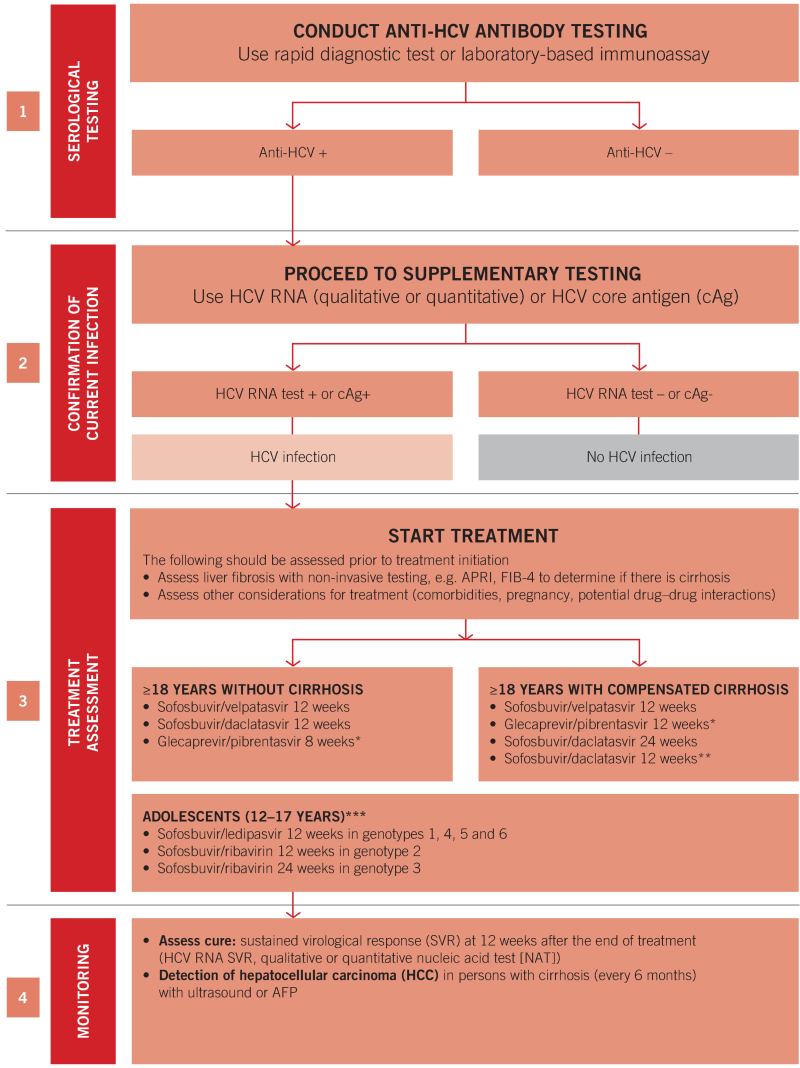

When to start treatment in adults and adolescents

WHO recommends offering treatment to all individuals diagnosed with HCV infection who are 12 years of age or older,1

irrespective of disease stage

(Strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence)

What treatment to use for adults and adolescents

WHO recommends the use of pangenotypic DAA regimens for the treatment of persons with chronic HCV infection aged 18 years and above.2

(Conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence)

In adolescents aged 12–17 years or weighing at least 35 kg with chronic HCV infection, WHO recommends:

sofosbuvir/ledipasvir for 12 weeks in genotypes 1, 4, 5 and 6

sofosbuvir/ribavirin for 12 weeks in genotype 2

sofosbuvir/ribavirin for 24 weeks in genotype 3.

(Strong recommendation/very low quality of evidence)

Pangenotypic regimens currently available for use in adults 18 years of age or older

For adults without cirrhosis, the following pangenotypic regimens can be used:

For adults with compensated cirrhosis, the following pangenotypic regimens can be used:

Treatment of children 0–12 years of age

In children aged less than 12 years with chronic HCV infection, WHO recommends:

(conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

(strong recommendation, very low quality of evidence)5

Clinical considerations

General clinical considerations

The use of pangenotypic regimens obviates the need for genotyping before treatment initiation.

In resource-limited settings, WHO recommends that the assessment of liver fibrosis should be performed using non-invasive tests (e.g. aspartate/platelet ratio index (APRI) score or FIB-4 test, see existing recommendations, p. xvii). This can determine if there is cirrhosis before initiation of treatment.

There are a few contraindications to using pangenotypic DAAs together with other medicines.

DAAs are well tolerated, with only minor side-effects. Therefore, the frequency of routine laboratory toxicity monitoring can be limited to a blood specimen at the start and end of treatment.

Following completion of DAA treatment, sustained virological response (SVR) at 12 weeks after the end of treatment is used to determine treatment outcomes (See existing recommendations, p. xvii).

Retreatment after DAA treatment failure

Currently, only one pangenotypic DAA regimen, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir, is approved by a stringent regulatory authority for the retreatment of persons who have previously failed DAA treatment.

Investigations of a failure to achieve SVR with DAA therapy includes re-examination of adherence and of potential drug–drug interactions.

Simplified service delivery models

An eight-point approach to service delivery supports implementation of the clinical recommendations for Treat All and adoption of pangenotypic DAA regimens:

Comprehensive national planning for the elimination of HCV infection;

Simple and standardized algorithms across the continuum of care;

Integration of hepatitis testing, care and treatment with other services;

Strategies to strengthen linkage from testing to care, treatment and prevention;

Decentralized services, supported by task-sharing;

Community engagement and peer support to address stigma and discrimination, and reach vulnerable or disadvantaged communities;

Efficient procurement and supply management of medicines and diagnostics;

Data systems to monitor the quality of individual care and the cascade of care.

Public health considerations in specific populations

Five population groups (people who inject drugs [PWID], people in prisons or other closed settings, men who have sex with men, sex workers and indigenous populations) require specific public health approaches because of one or more of the following specific issues: high incidence, high prevalence, stigma, discrimination, criminalization or vulnerability, and difficulties in accessing services.

Summary of the existing WHO recommendations

Who to test for HCV infection? (2017 testing guidelines) (3)

1. Focused testing in most-affected populations. In all settings (and regardless of whether delivered through facility- or community-based testing), it is recommended that serological testing for HCV antibody (anti-HCV)1 be offered with linkage to prevention, care and treatment services to the following individuals:

Adults and adolescents from populations most affected by HCV infection

2 (i.e. who are either part of a population with high HCV seroprevalence or who have a history of exposure and/or high-risk behaviours for HCV infection);

Adults, adolescents and children with a clinical suspicion of chronic viral hepatitis

3 (i.e. symptoms, signs, laboratory markers).

(Strong recommendation, low quality of evidence)

Note: Periodic retesting using HCV nucleic acid tests (NAT) should be considered for those with ongoing risk of acquisition or reinfection.

2. General population testing. In settings with a ≥2% or ≥5%4 HCV antibody seroprevalence in the general population, it is recommended that all adults have access to and be offered HCV serological testing with linkage to prevention, care and treatment services.

General population testing approaches should make use of existing community- or facility-based testing opportunities or programmes such as HIV or TB clinics, drug treatment services and antenatal clinics.5

(Conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence)

3. Birth cohort testing. This approach may be applied to specific identified birth cohorts of older persons at higher risk of infection6 and morbidity within populations that have an overall lower general prevalence.

(Conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence)

- 1

This may include fourth-generation combined antibody/antigen assays.

- 2

Includes those who are either part of a population with higher seroprevalence (e.g. some mobile/migrant populations from high/intermediate endemic countries, and certain indigenous populations) or who have a history of exposure or high-risk behaviours for HCV infection (e.g. PWID, people in prisons and other closed settings, men who have sex with men and sex workers, and HIV-infected persons, children of mothers with chronic HCV infection especially if HIV-coinfected).

- 3

Features that may indicate underlying chronic HCV infection include clinical evidence of existing liver disease, such as cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), or where there is unexplained liver disease, including abnormal liver function tests or liver ultrasound.

- 4

A threshold of ≥2% or ≥5% seroprevalence was based on several published thresholds of intermediate and high seroprevalence. The threshold used will depend on other country considerations and epidemiological context.

- 5

Routine testing of pregnant women for HCV infection is currently not recommended.

- 6

Because of historical exposure to unscreened or inadequately screened blood products and/or poor injection safety.

How to test for chronic HCV infection and monitor treatment response? (2017 testing guidelines) (3)

1. Which serological assay to use? To test for serological evidence of past or present infection in adults, adolescents and children (>18 months of age),1 an HCV serological assay (antibody or antibody/antigen) using either a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) or laboratory-based immunoassay formats2 that meet minimum safety, quality and performance standards3

(with regard to both analytical and clinical sensitivity and specificity) is recommended.

In settings where there is limited access to laboratory infrastructure and testing, and/or in populations where access to rapid testing would facilitate linkage to care and treatment, RDTs are recommended.

(Strong recommendation, low/moderate quality of evidence)

2. Serological testing strategies. In adults and children older than 18 months, a single serological assay for initial detection of serological evidence of past or present infection is recommended prior to supplementary nucleic acid testing (NAT) for evidence of viraemic infection.

(Conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence)

3. Detection of viraemic infection

(Strong recommendation, moderate/low quality of evidence)

(Conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence)4

4. Assessment of HCV treatment response

(Conditional recommendation, moderate/low quality of evidence)

- 1

HCV infection can be confirmed in children under 18 months only by virological assays to detect HCV RNA, because transplacental maternal antibodies remain in the child’s bloodstream up until 18 months of age, making test results from serology assays ambiguous.

- 2

Laboratory-based immunoassays include enzyme immunoassay (EIA), chemoluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) and electrochemoluminescence assay (ECL).

- 3

Assays should meet minimum acceptance criteria of either WHO prequalification of in vitro diagnostics (IVDs) or a stringent regulatory review for IVDs. All IVDs should be used in accordance with manufacturers’ instructions, and where possible at testing sites enrolled in a national or international external quality assessment scheme.

- 4

A lower level of analytical sensitivity can be considered if an assay is able to improve access (i.e. an assay that can be used at the point of care or is suitable for dried blood spot [DBS] specimens) and/or affordability. An assay with a limit of detection of 3000 IU/mL or lower would be acceptable and would identify 95% of those with viraemic infection, based on the available data.

Screening for alcohol use and counselling to reduce moderate and high levels of alcohol intake (2016 treatment guidelines) (2)

An alcohol intake assessment is recommended for all persons with HCV infection followed by the offer of a behavioural alcohol reduction intervention for persons with moderate-to-high alcohol intake.

(Strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence)

Assessing degree of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis (2016 treatment guidelines) (2)

In resource-limited settings, it is suggested that the aminotransferase/platelet ratio index (APRI) or FIB-4 tests be used for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis rather than other non-invasive tests that require more resources such as elastography or FibroTest.

(Conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence)

- 1

With the exception of pregnant women

- 2

The Guidelines Development Group defined pangenotypic regimens as those leading to a SVR rate >85% across all six major HCV genotypes.

- 3

Persons with HCV genotype 3 infection who have received interferon and/or ribavirin in the past should be treated for 16 weeks.

- 4

May be considered in countries where genotype distribution is known and genotype 3 prevalence is <5%.

- 5

Prior to approval of DAAs for children aged <12 years of age, exceptional treatment with interferon + ribavirin may be considered for children with genotype 2 or 3 infection and severe liver disease. This may include children at higher risk of progressive disease, such as with HIV coinfection, thalassaemia major and survivors of childhood cancer.