1. Introduction

The optimal preparation of the bowel of patients undergoing colorectal surgery has been a subject of debate for many years. The main focus has been on whether or not mechanical cleansing of the bowel should be part of the standard preoperative regimen. Mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) involves the preoperative administration of substances to induce voiding of the intestinal and colonic contents. The most commonly used cathartics for MPB are polyethylene glycol and sodium phosphate. It was assumed that cleaning the colon of its contents was necessary for a safe operation and could lower the risk of surgical site infection (SSI) by decreasing the intraluminal fecal mass and theoretically decreasing the bacterial load in the intestinal lumen. Furthermore, it was believed that it could prevent the possible mechanical disruption of a constructed anastomosis by the passage of hard faeces. Finally, MBP was perceived to improve handling of the bowel intraoperatively.

Another aspect of preoperative bowel preparation that has evolved over the last decades concerns the administration of oral antibiotics. Orally administered antibiotics have been used since the 1930s with the aim to decrease the intraluminal bacterial load. However, these drugs had typically poor absorption, achieved high intraluminal concentrations and had activity against (anaerobic and aerobic) species within the colon. The addition of oral antibiotics that selectively target potentially pathogenic microorganisms originating from the digestive tract, predominantly gram-negative bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and yeasts, is known also as “selective digestive decontamination”. This term originates from intensive care medicine and usually refers to a regime of tobramycin, amphotericin and polymyxin combined with a course of an intravenous antibiotic, often cefotaxime. Originating from the belief that oral antibiotics would work only when the bowel had been cleansed of its contents, a regime of oral antibiotics was frequently combined with MBP.

Several organizations have issued recommendations regarding preoperative MBP and the administration of oral antibiotics. Most recommend to use MBP for colorectal procedures, but only combined with oral antibiotics. The United Kingdom (UK) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend not to use MBP routinely to reduce the risk of SSI (1). The SSI prevention guidelines issued in 1999 by the United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend MBP before elective colorectal operations in combination with the administration of non-absorbable oral antimicrobial agents in divided doses on the day before the operation (2). The most recent guideline on this topic was issued by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and recommends using a combination of parenteral antimicrobial agents and oral antimicrobials to reduce the risk of SSI following colorectal procedures. It is emphasized that MBP without oral antimicrobials does not decrease the risk of SSI (3).

The purpose of this systematic review is to assess the available evidence on the effectiveness of preoperative oral antibiotics and MBP for the prevention of SSI.

2. PICO question

Is MBP combined with or without oral antibiotics effective for the prevention of SSI in colorectal surgery?

3. Methods

The following databases were searched: Medline (Ovid); Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and WHO regional medical databases. The time limit for the review was between 1 January 1990 and 17 January 2014. Language was restricted to English, French and Spanish. A comprehensive list of search terms was used, including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) (Appendix 1).

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved references for potentially relevant studies. The full text of all potentially eligible articles was obtained and then reviewed independently by two reviewers for eligibility based on inclusion criteria. Duplicate studies were excluded.

The two reviewers extracted data in a predefined evidence table (Appendix 2) and critically appraised the retrieved studies. Quality was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool to assess the risk of bias of randomized controlled studies (RCTs) (4) (Appendix 3). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or after consultation with the senior author, when necessary.

Meta-analyses of available comparisons were performed using Review Manager version 5.3 as appropriate (5) (Appendix 4). Adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted and pooled for each comparison with a random effects model. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology (6) (GRADE Pro software) (7) was used to assess the quality of the body of retrieved evidence (Appendix 5).

4. Study selection

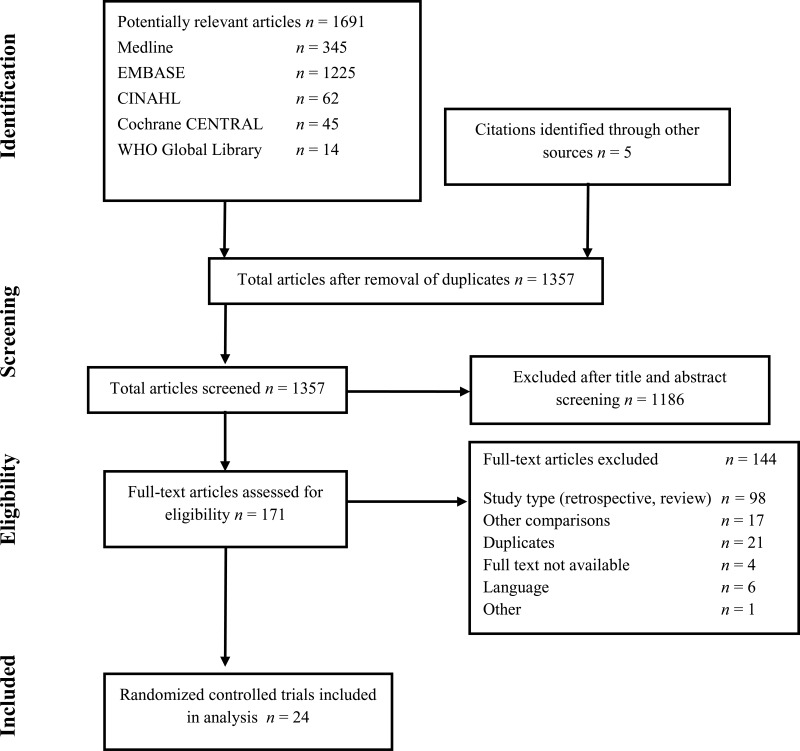

Flow chart of the study selection process

5. Summary of the findings and quality of the evidence

A total of 24 RCTs (8–31) were identified either comparing MBP vs. no MBP or a combined intervention of MBP and oral antibiotics vs. MBP and no oral antibiotics. Most studies assessed the outcome of anastomotic leakage, while all assessed SSIs. Included patients were adults undergoing colorectal surgical procedures. No study was available in the paediatric population. All patients received antibiotic prophylaxis prior to surgery, both in the intervention and control groups.

According to the interventions, we were able to make the following comparisons:

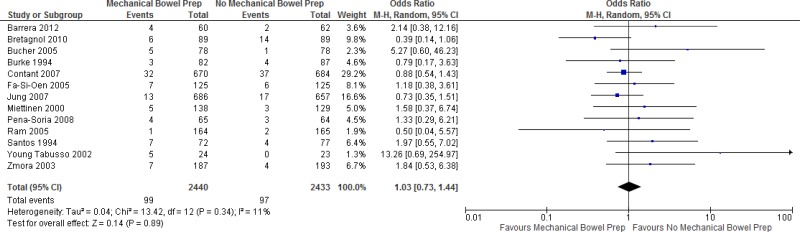

MBP and oral antibiotics vs. MBP and no oral antibiotics

Among the 11 RCTs (

13,

15,

16,

18,

19,

21,

24,

25,

27–

29) comparing

MBP combined with oral antibiotics vs. MBP and no oral antibiotics, 6 trials (

13,

15,

18,

24,

27,

28) showed no statistically significant difference in the

SSI rate between the 2 groups. Five RCTs (

16,

19,

21,

25,

29) showed a decrease of the SSI rate in patients undergoing MBP combined with oral antibiotics prior to the operation. In 8 trials, oral aminoglycosides were combined with anaerobic coverage (metronidazole (

13,

19,

21,

25,

28) or erythromycin (

16,

18,

27)) and 3 studies (

15,

24,

29) applied a gram-negative coverage only. In these 8 RCTs (

13,

16,

18,

19,

21,

25,

27,

28), a combination of non-absorbable and absorbable antibiotics were administered, whereas 2 studies (

15,

24) applied non-absorbable and one study (

29) absorbable antibiotics only.

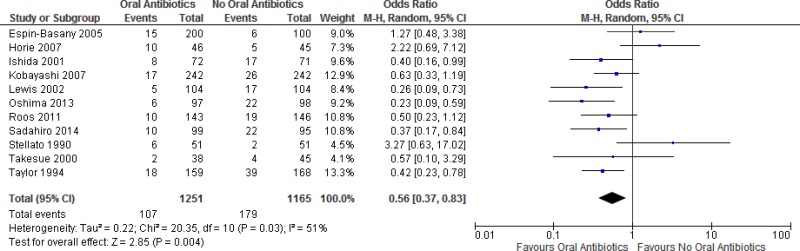

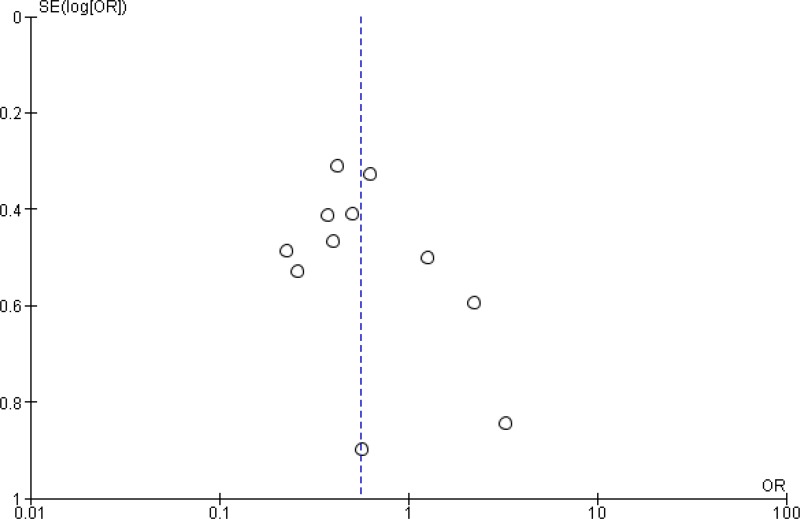

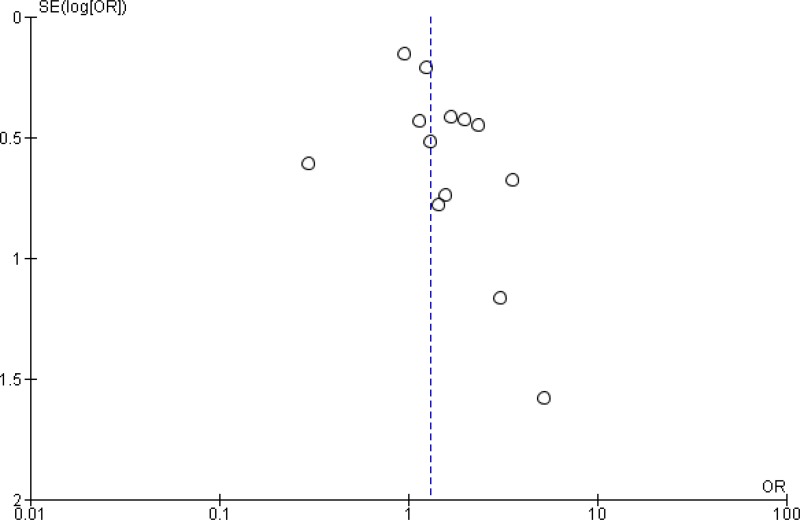

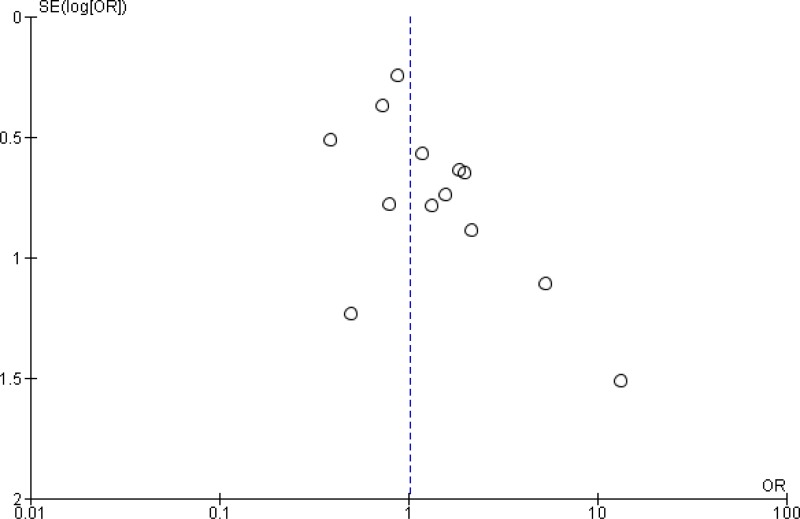

A meta-analysis of the 11 trials (

Appendix 4, ) showed that preoperative oral antibiotics combined with

MBP reduce the

SSI rate when compared to MBP only (

OR: 0.56; 95%

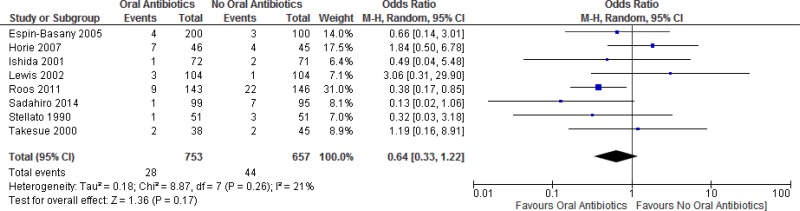

CI: 0.37–0.83). There was no difference in the occurrence of anastomotic leakage (OR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.33–1.22;

Appendix 4, ).

The quality of the evidence for this comparison was moderate due to the risk of bias (

Appendix 5).

Two trials (

27,

29) reported specifically on

SSI-attributable mortality. Both studies reported a lower mortality rate when oral antibiotics were administered, although they failed to report a test for statistical significance.

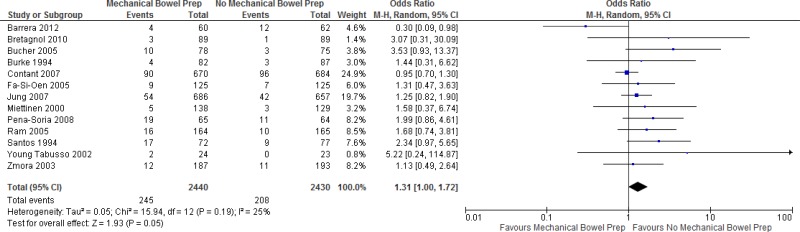

Thirteen trials comparing

MBP vs. no MBP were identified. Of these, 12 trials (

9–

12,

14,

17,

20,

22,

23,

26,

30,

31) showed no statistically significant difference in the

SSI rate between performing a preoperative MBP vs. not doing so. One study (

8) showed a decrease of SSI when MBP was performed prior to the operation. Polyethylene glycol and/or sodium phosphate were the predominant agents of choice for MBP, although the protocols differed between the studies in terms of dosage and/or timing of the application. In 2 studies (

10,

31), patients undergoing rectal surgery were additionally given a single enema in both the intervention and the control group.

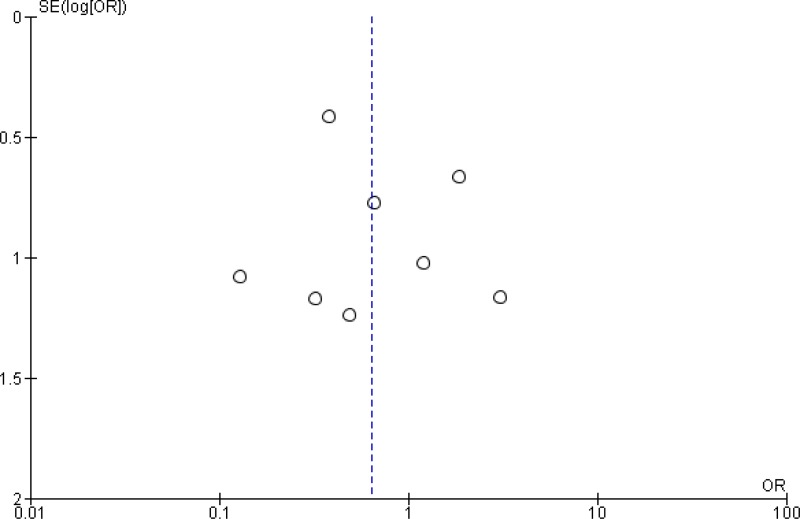

A meta-analysis of the 13 trials (

Appendix 4, ) showed that preoperative

MBP has neither benefit nor harm in reducing the

SSI rate when compared to not carrying out a MBP at all (

OR: 1.31; 95%

CI: 1.00–1.72). In addition, a separate meta-analysis based on these studies (

Appendix 4, ) showed no difference in the occurrence of anastomotic leakage with or without MBP (OR: 1.03; 95% CI: 0.73–1.44).

The quality of the evidence for this comparison was moderate due to the risk of bias (Appendix 5).

Three trials reported specifically on SSI-attributable mortality (11, 22, 31). None of the 3 studies reported on a statistical difference in the mortality rate.

In conclusion, the available evidence can be summarized as follows.

- -

MBP and oral antibiotics versus MBP and no oral antibiotics (Appendix 4, )

Overall, a moderate quality of evidence shows that preoperative oral antibiotics combined with MBP reduce the SSI rate when compared to MBP only.

- -

Preoperative MBP versus no MBP (Appendix 4, )

Overall, a moderate quality of evidence shows that preoperative MBP has no benefit in reducing the SSI rate when compared to not carrying out MBP at all.

There was a heterogeneity regarding the protocols across the included studies. Polyethylene glycol and/or sodium phosphate were the agents of choice for MBP in most studies. The protocols differed between the trials in terms of dosage and/or timing of the application and fasting. Apart from the MBP regimen, the oral antibiotics and the drug of choice for intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis varied across the studies. In 8 trials, oral aminoglycosides were combined with anaerobic coverage (metronidazole (13, 19, 21, 25, 28) or erythromycin (16, 18, 27)) and 3 studies (15, 24, 29) applied a gram-negative coverage only. In the studies included for the comparison of MBP vs. no MBP, all patients received intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis according to the local protocol. In 2 of these studies, oral antibiotics were given also as part of a standard procedure to patients in both study groups. Most studies had a considerable risk of bias, particularly related to blinding of outcome assessors.

6. Other factors considered in the review of studies

The systematic review team identified the following other factors to be considered.

Potential harms

Overall, the meta-analyses results show that the use of antibiotics combined with MBP for preoperative bowel preparation reduces the incidence of SSI, which can be an expensive and complicated condition to treat. However, there are concerns about inducing potential antibiotic resistance and adverse events related to the oral antibiotics used (for example, high risk of idiosyncratic reaction with erythromycin). These harms could be even more important if the oral antibiotics are continued postoperatively as this intervention is restricted to the preoperative period only. Patient discomfort, electrolyte abnormalities and possible severe dehydration at the time of anaesthesia and incision are further concerns potentially associated with the use of MBP.

Values and preferences

Six studies comparing MBP combined with oral antibiotics vs. MBP alone reported on patient discomfort. One study (15) found a higher incidence of diarrhoea when oral antibiotics were administered. Another study (13) assessed patient tolerance with 3 different oral antibiotic regimes. Patients reported more gastrointestinal symptoms (that is, nausea and vomiting) at the time of preoperative preparation when given 3 doses of oral antibiotics compared to no oral antibiotics or one dose only. The remaining 4 studies (18, 19, 21, 25) found no differences in terms of adverse events such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain related to the addition of oral antibiotics.

Among the studies comparing MBP with no MBP, 4 reported on patient discomfort. Barrera and colleagues (8) reported that half of all patients (50%) receiving MBP reported fair or poor tolerance. Main causes were related to symptoms of nausea (56%), vomiting (23%) and cramping abdominal pain (15%). In another study (9) including 89 patients with MBP, 17% complained of nausea or vomiting, 18% of abdominal pain and 28% about abdominal bloating. These disorders led to a stop of preoperative MBP in 11% of cases. In one study (10), MBP was associated with discomfort in 22% of patients, including difficulty in drinking the preparation, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. Zmora and colleagues (31) found that diarrhoea in the early postoperative period was more common in the MBP compared to the non-MBP group and this difference reached statistical significance.

7. Key uncertainties and future research priorities

The systematic review team identified the following key uncertainties and future research priorities. Based on available evidence, no recommendation on the preferred type and dose of oral antibiotics can be made. Further research is needed on the effects of using oral antibiotics without MBP for the reduction of SSI rates, particularly well-designed RCTs comparing oral antibiotics and standard intravenous prophylactic antibiotics vs. standard intravenous prophylactic antibiotics only. A few studies evaluated the role of these interventions for patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures, but this merits further research and more studies are needed to draw firm conclusions. Some observational studies of mixed populations undergoing open and laparoscopic procedures suggested benefits from MBP across all groups. A RCT was recently published on this topic, but it could not be included in the systematic review due to the time limits of study inclusion. This study showed a significant reduction of SSI in laparoscopic patients receiving oral antibiotics in addition to MBP and standard intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis (32).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search terms

Medline (via OVID)

- 1.

colorectal surgery/ or (colorectal surger* or colon surg* or rectal surger* or proctolog* or proctocolonic surg* or intestine surger*).ti,ab,kw.

- 2.

exp anti-bacterial Aagents/ or antibiotic prophylaxis/ or antibiotic*.ti,ab,kw.

- 3.

surgical wound infection/ or (surgical site infection* or SSI or SSIs or surgical wound infection* or surgical infection* or post-operative wound infection* or postoperative wound infection*).ti,ab,kw.

- 6.

wound infection.mp. or exp wound infection/

- 7.

exp infection control/ or exp decontamination/ or exp bacterial infections/ or exp gastrointestinal tract/ or exp digestive system/ or exp intensive care units/ or exp sulfones/ or exp anti-bacterial agents/ or exp cross infection/ or SDD.mp. or exp toxoplasmosis, animal/

- 8.

decontamination.mp. or exp decontamination/

- 9.

exp laxatives/ or (laxative* or laxantia* or purgative or cathartic agent or cathartic*).ti,ab,kw. or (bowel preparat* or intestine preparat* or colon preparat*).ti,ab,kw.

- 10.

oral drug administration/ or oral*.ti,ab,kw.

- 11.

2 and 10

- 12.

7 or 8 or 9 or 11

- 13.

3 or 6

- 14.

1 and 12 and 13

- 15.

limit 14 to yr=“1990 -Current”

EMBASE

exp wound infection/

exp colorectal surgery/ or exp colon surgery/ or intestine surgery/ or (colorectal surger* or colon surg* or rectal surger* or proctolog* or proctocolonic surg* or intestine surger*).ti,ab,kw.

exp antibiotic agent/ or antibiotic prophylaxis/ or antibiotic*.ti,ab,kw.

surgical infection/ or (surgical site infection* or

SSI or SSIs or surgical wound infection* or surgical infection* or post-operative wound infection* or postoperative wound infection*).ti,ab,kw.

2 and 3 and 4

limit 5 to yr=“1990 - 2014”

1 or 4

2 and 3 and 7

exp bacterial infection/ or exp colistin/ or exp cefotaxime/ or exp intensive care/ or exp digestive system/ or exp intensive care unit/ or exp amphotericin B/ or exp tobramycin/ or exp antibiotic agent/ or sdd.mp. or exp sulfone/

decontaminat*.mp.

oral drug administration/ or oral*.ti,ab,kw.

3 and 11

9 or 10 or 12

2 and 7 and 13

exp laxative/ or (laxative* or laxantia* or purgative or cathartic agent or cathartic*).ti,ab,kw. or (bowel preparat* or intestine preparat* or colon preparat*).ti,ab,kw.

9 or 10 or 12 or 15

2 and 7 and 16

limit 17 to yr=“1990 -Current”

CINAHL

(MH “wound infection”)

(MH “surgical wound infection”)

(“wound infection”)

(MH “colorectal surgery”)

(“colon surgery”)

(“rectal surgery”)

(MH “mechanical bowel preparation”)

(“colon preparation”)

(“intestinal preparation”)

(MH “administration, oral”)

(MH “antibiotics”)

1 or 2 or 3

4 or 5 or 6

7 or 8 or 9

10 and 11

14 or 15

12 and 13 and 16

Cochrane CENTRAL

wound infection:ti,ab,kw

surgical wound infection:ti,ab,kw

colorectal surgery:ti,ab,kw

selective digestive decontamination:ti,ab,kw

“oral antibiotic”:ti,ab,kw

mechanical bowel preparation:ti,ab,kw

1 or 2

4 or 5 or 6

7 and 3 and 8

WHO regional medical databases

(ssi)

(surgical site infection)

(surgical site infections)

(Wound infection)

(Wound infections)

(postoperative wound infection)

(digestive decontamination)

(oral antibiotics)

(sdd)

(mechanical bowel)

(bowel preparation)

(colorectal surgery)

(colon surgery)

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6

7 or 8 or 9

10 or 11

12 or 13

15 or 16

14 and 17 and 18

African Index Medicus

infection [key word]

surgical [key word]

surgery [key word]

2 or 3

1 and 4

- ti:

title;

- ab:

abstract;

- kw:

key word

Appendix 2. Evidence table

Appendix 2a. Studies on MBP and oral antibiotics vs. MBP and no oral antibiotics

Download PDF (230K)

Appendix 3. Risk of bias assessment of the included studies

Appendix 3a. Studies on MBP and oral antibiotics vs. MBP and no oral antibiotics

View in own window

| Author, year, reference | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Participants blinded | Care providers blinded | Outcome assessors blinded | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|

| Espin-Basany, 2005 (13) | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Horie, 2007 (15) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Ishida, 2001 (16) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Kobayashi, 2007 (18) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Lewis, 2002 (19) | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Oshima, 2013 (21) | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Roos, 2011 (24) | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Sadahiro, 2014 (25) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Stellato, 1990 (27) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Takesue, 2000 (28) | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Taylor, 1994 (29) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

MBP: mechanical bowel preparation

Appendix 3b. Studies on MBP vs. no MBP

View in own window

| Author, year, reference | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Participants blinded | Care providers blinded | Outcome assessors blinded | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|

| Barrera, 2012 (8) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Bretagnol, 2010 (9) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Bucher, 2005 (10) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Burke, 1994 (11) | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Contant, 2007 (12) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Fa-Si-Oen, 2005 (14) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Jung, 2007 (17) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Miettinen, 2000 (20) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Pena-Soria, 2008 (22) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Ram, 2005 (23) | High risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Santos, 1994 (26) | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Young Tabusso, 2002 (30) | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | - |

| Zmora, 2003 (31) | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | - |

MBP: mechanical bowel preparation

References

- 1.

Leaper

D, Burman-Roy

S, Palanca

A, Cullen

K, Worster

D, Gautam-Aitken

E, et al. Prevention and treatment of surgical site infection: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;337. [

PubMed: 18957455]

- 2.

Mangram

AJ, Horan

TC, Pearson

ML, Silver

LC, Jarvis

WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:97–132; quiz 3–4; discussion 96. [

PubMed: 10196487]

- 3.

Anderson

DJ, Podgorny

K, Berríos-Torres

SI, DW, Dellinger

EP, Greene

L, et al. Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control. 2014;35:605–27. [

PMC free article: PMC4267723] [

PubMed: 24799638]

- 4.

Higgins

JP, Altman

DG, Gotzsche

PC, Juni

P, Moher, Oxman

AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [

PMC free article: PMC3196245] [

PubMed: 22008217]

- 5.

The Nordic Cochrane Centre TCC. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

- 6.

Guyatt

G, Oxman

AD, Akl

EA, Kunz

R, Vist

G, Brozek

J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–94. [

PubMed: 21195583]

- 7.

GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool. Summary of findings tables, health technology assessment and guidelines. GRADE Working Group, Ontario: McMaster University and Evidence Prime Inc.; 2015 (

http://www.gradepro.org, accessed 5 May 2016).

- 8.

Barrera

EA, Cid

BH, Bannura

CG, Contreras

PJ, Zuniga

TC, Mansilla

EJ. [Utilidad de la preparación mecánica anterógrada en cirugía colorrectal electiva. Resultados de una serie prospectiva y aleatoria.] [Article in Spanish] Rev Chilena Cir. 2012;64:373–7.

- 9.

Bretagnol

F, Panis

Y, Rullier

E, Rouanet

P, Berdah

S, Dousset

B, et al. Rectal cancer surgery with or without bowel preparation: The French GRECCAR III multicenter single-blinded randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252:863–8. [

PubMed: 21037443]

- 10.

Bucher

P, Gervaz

P, Soravia

C, Mermillod

B, Erne

M, Morel

P. Randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation versus no preparation before elective left-sided colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2005;92:409–14. [

PubMed: 15786427]

- 11.

Burke

P, Mealy

K, Gillen

P, Joyce

W, Traynor

O, Hyland

J. Requirement for bowel preparation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81:907–10. [

PubMed: 8044619]

- 12.

Contant

CM, Hop

WC, van’t Sant

HP, Oostvogel

HJ, Smeets

HJ, Sassen

LP, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370:2112–7. [

PubMed: 18156032]

- 13.

Espin-Basany

E, Sanchez-Garcia

JL, Lopez-Cano

M, Lozoya-Trujillo

R, Medarde-Ferrer

M, Armadans-Gil

L, et al. Prospective, randomised study on antibiotic prophylaxis in colorectal surgery. Is it really necessary to use oral antibiotics?

Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:542–6. [

PubMed: 15843938]

- 14.

Fa-Si-Oen

P, Roumen

R, Buitenweg

J, van de Velde

C, van Geldere

D, Putter

H, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation or not? Outcome of a multicenter, randomized trial in elective open colon surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1509–16. [

PubMed: 15981065]

- 15.

Horie

T. Randomized controlled trial on the necessity of chemical cleaning as preoperative preparation for colorectal cancer surgery. Dokkyo J Med Sci. 2007;34.

- 16.

Ishida

H, Yokoyama

M, Nakada

H, Inokuma

S, Hashimoto

D. Impact of oral antimicrobial prophylaxis on surgical site infection and methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus infection after elective colorectal surgery. Results of a prospective randomized trial. Surg Today. 2001;31:979–83. [

PubMed: 11766085]

- 17.

Jung

B, Pahlman

L, Nystrom

PO, Nilsson

E. Multicentre randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation in elective colonic resection. Br J Surg. 2007;94:689–95. [

PubMed: 17514668]

- 18.

Kobayashi

M, Mohri

Y, Tonouchi

H, Miki

C, Nakai

K, Kusunoki

M. Randomized clinical trial comparing intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis alone with oral and intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis for the prevention of a surgical site infection in colorectal cancer surgery. Surg. Today. 2007;37:383–8. [

PubMed: 17468819]

- 19.

Lewis

RT. Oral versus systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in elective colon surgery: a randomized study and meta-analysis send a message from the 1990s. Can J Surg. 2002;45:173–80. [

PMC free article: PMC3686946] [

PubMed: 12067168]

- 20.

Miettinen

RP, Laitinen

ST, Makela

JT, Paakkonen

ME. Bowel preparation with oral polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution vs. no preparation in elective open colorectal surgery: prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:669–75; discussion 75–7. [

PubMed: 10826429]

- 21.

Oshima

T, Takesue

Y, Ikeuchi

H, Matsuoka

H, Nakajima

K, Uchino

M, et al. Preoperative oral antibiotics and intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis reduce the incidence of surgical site infections in patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing IPAA. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1149–55. [

PubMed: 24022532]

- 22.

Pena-Soria

MJ, Mayol

JM, Anula

R, Arbeo-Escolar

A, Fernandez-Represa

JA. Single-blinded randomized trial of mechanical bowel preparation for colon surgery with primary intraperitoneal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:2103–8; discussion 8–9. [

PubMed: 18820977]

- 23.

Ram

E, Sherman

Y, Weil

R, Vishne

T, Kravarusic

D, Dreznik

Z. Is mechanical bowel preparation mandatory for elective colon surgery? A prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. 2005;140:285–8. [

PubMed: 15781794]

- 24.

Roos

D, Dijksman

LM, Oudemans-van Straaten

HM, de Wit

LT, Gouma

DJ, Gerhards

MF. Randomized clinical trial of perioperative selective decontamination of the digestive tract versus placebo in elective gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1365–72. [

PubMed: 21751181]

- 25.

Sadahiro

S, Suzuki

T, Tanaka

A,Okada

K, Kamata

H, Ozaki

T, et al. Comparison between oral antibiotics and probiotics as bowel preparation for elective colon cancer surgery to prevent infection: prospective randomized trial. Surgery. 2014;155:493–503. [

PubMed: 24524389]

- 26.

Santos

JC, Jr., Batista

J, Sirimarco

MT, Guimaraes

AS, Levy

CE. Prospective randomized trial of mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1673–6. [

PubMed: 7827905]

- 27.

Stellato

TA, Danziger

LH, Gordon

N, Hau

T, Hull

CC, Zollinger

RM, Jr, et al. Antibiotics in elective colon surgery. A randomized trial of oral, systemic, and oral/systemic antibiotics for prophylaxis. Am Surg. 1990;56:251–4. [

PubMed: 2194417]

- 28.

Takesue

Y, Yokoyama

T, Akagi

S, Ohge

H, Murakami

Y, Sakashita

Y, et al. A brief course of colon preparation with oral antibiotics. Surg Today. 2000;30:112–6. [

PubMed: 10664331]

- 29.

Taylor

EW, Lindsay

G. Selective decontamination of the colon before elective colorectal surgery. West of Scotland Surgical Infection Study Group. World J Surg. 1994;18:926–31; discussion 31–2. [

PubMed: 7846921]

- 30.

Young Tabusso

F, Celis Zapata

J, Berrospi Espinoza

F, Payet Meza

E, Ruiz Figueroa

E. [Mechanical preparation in elective colorectal surgery, a usual practice or a necessity?]. [Article in Spanish] Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2002;22:152–8. [

PubMed: 12098743]

- 31.

Zmora

O, Mahajna

A, Bar-Zakai

B, Rosin

D, Hershko

D, Shabtai, et al. Colon and rectal surgery without mechanical bowel preparation: a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2003;237:363–7. [

PMC free article: PMC1514315] [

PubMed: 12616120]

- 32.

Hata

H, Yamaguchi

T, Hasegawa

S, Nomura

A, Hida

K, Nishitai

R, et al. Oral and parenteral versus parenteral antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery (JMTO PREV 07-01): a phase 3, multicenter, open-label, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2016;263:1085–91. [

PubMed: 26756752]