1. Introduction

The endogenous bacteria on a patient’s skin is believed to be the main source of pathogens that contribute to surgical site infection (SSI)1. The standard of care in preoperative surgical site skin preparation includes scrubbing or applying alcohol-based preparations containing antiseptic agents prior to incision, such as chlorhexidine gluconate or iodine solutions. These agents are considered effective against a wide range of bacteria, fungi and viruses. Additional technologies are being researched and developed to reduce the rate of contamination and subsequent SSI.

Antimicrobial skin sealants are sterile, film-forming cyanoacrylate-based sealants that are commonly used as additional antimicrobial skin preparation after antisepsis and prior to skin incision. These sealants are intended to remain in place and block the migration of flora from surrounding skin into the surgical site by dissolving for several days postoperatively. As an antimicrobial substance, sealants have been shown to reduce bacterial counts on the skin of the operative site. However, their use in surgical site preparation to prevent SSI is still under debate. In a recent review of the literature, Dohmen and colleagues highlighted that antimicrobial sealants decrease skin flora contamination and bacterial growth and cited some studies demonstrating a significant reduction of SSIs following the use of sealants2.

Currently available SSI prevention guidelines do not comment on the use of antimicrobial skin sealants and their effect to prevent SSI. The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the effect of the use of antimicrobial sealants to prevent SSI.

2. PICO question

In surgical patients, should antimicrobial sealants (in addition to standard surgical site skin preparation) vs. standard surgical site skin preparation be used for the prevention of SSI?

Population: inpatients and outpatients of any age undergoing surgical operations (any type of procedure)

Intervention: antimicrobial sealant in addition to standard surgical site skin preparation

Comparator: standard surgical site skin preparation

3. Methods

The following databases were searched: Medline (PubMed); Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and the WHO Global Health Library. The time limit for the review was between 1 January 1990 and 31 March 2015. Language was restricted to English, French and Spanish. A comprehensive list of search terms was used, including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) (Appendix 1).

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved references for potentially relevant studies. The full text of all potentially eligible articles was obtained. Two authors independently reviewed the full text articles for eligibility based on inclusion criteria. Duplicate studies were excluded.

Two authors extracted data in a predefined evidence table (Appendix 2) and critically appraised the retrieved studies. Quality was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool3 to assess the risk of bias of randomized controlled studies (Appendix 3). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or after consultation with the senior author, when necessary.

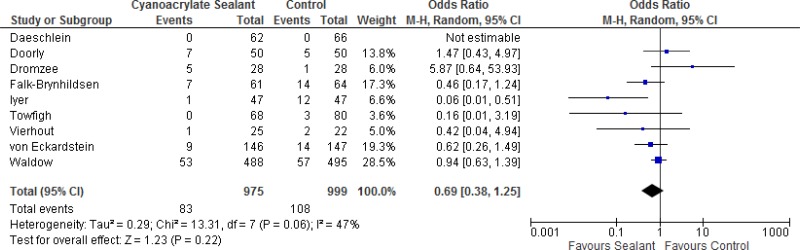

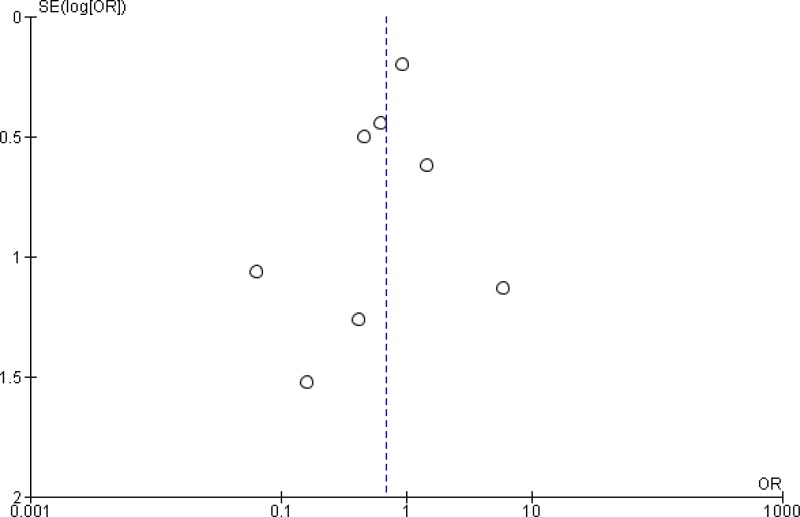

Meta-analyses of available comparisons were performed using Review Manager v5.34 as appropriate (Appendix 4). Adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted and pooled for each comparison with a random effects model. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology (GRADE Pro software, http://gradepro.org/)5 was used to assess the quality of the body of retrieved evidence (Appendix 5).

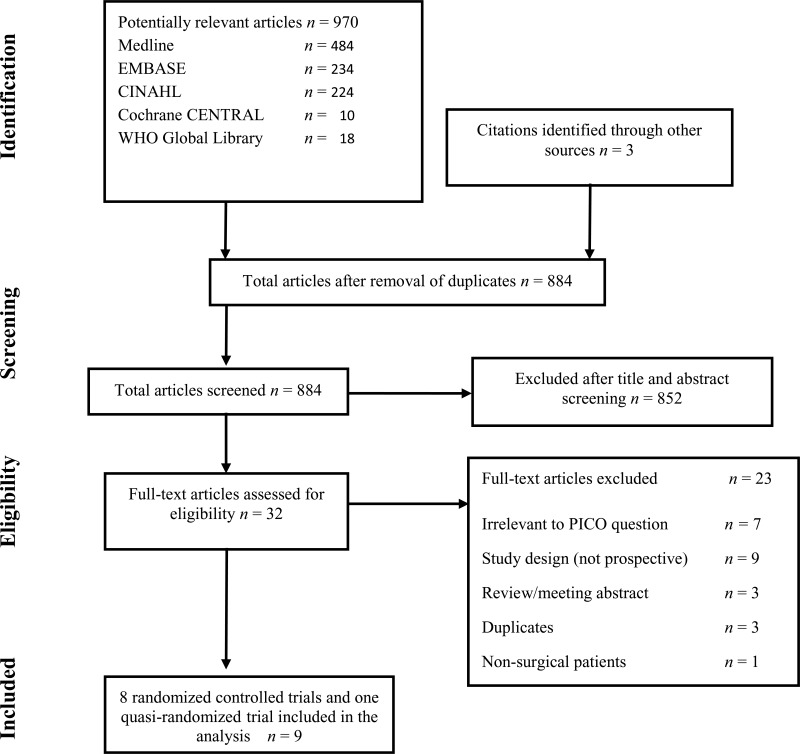

4. Study selection

Flow chart of the study selection process

5. Summary of the findings and quality of the evidence

Eight randomized clinical trials (RCTs)6–13 and one prospective, quasi-randomized trial14 with SSI outcome were identified. They evaluated antimicrobial sealants compared to standard surgical site preparation with antiseptics for the prevention of SSI. All 9 studies compared a cyanoacrylate-based sealant to standard antiseptic preparation without sealant.

One study8 included children and adults, while the remaining 8 included adult patients only. Both elective and emergency procedures were included; the types of surgery were cardiac, vascular, colorectal, hernia repair, scoliosis correction and trauma. In each study, the intervention and control groups received the same surgical site skin preparation with the addition of antimicrobial sealant in the intervention groups. The type and concentration of skin preparation varied. Some studies used chlorhexidine gluconate, while others used povidone iodine, all in an alcohol-based solution.

The effects of the intervention on the prevention of SSI varied among studies. One study10 reported that antimicrobial sealants may have some benefit compared to standard skin preparation. Five studies9,11–14 showed some effect of antimicrobial sealants, but the effect estimate was not statistically different compared to the standard skin preparation. Two studies7,8 found that antimicrobial sealants may cause harm, but this effect was not statistically significant.

Meta-analysis of the 8 RCTs and the quasi-randomized trial showed that there was no overall difference between antimicrobial sealants and standard surgical skin preparation in reducing the incidence of SSI (odds ratio [OR]: 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.38–1.25) (Appendix 4). In a sensitivity analysis comparing the overall effect of the included studies with or without the quasi-randomized trial, there was no difference in the results if the trial was included or not (P=0.658). The overall quality of evidence of the identified studies for this systematic review was very low due to a serious risk of bias and very serious imprecision (Appendix 5).

In conclusion, the retrieved evidence can be summarized as follows: very low quality evidence showed that the preoperative use of antimicrobial sealants has neither benefit nor harm in reducing SSI rates when compared to standard surgical site skin preparation.

However, some studies have major limitations. Many trials were small and there was a variation in the definition of SSI across studies. Within the analysis, there was also a lack of consistency in the effects of the intervention on the prevention of SSI. Of note, most studies were funded by the manufacturers of commercial sealants. A serious risk of bias was detected, mainly due to unclear blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting.

6. Other factors considered in the review

The systematic review team identified the following other factors to be considered.

Potential harms

As antimicrobial sealants remain on the skin for a longer period than standard surgical site preparation, potential harms to further consider include adverse effects on the skin. Only one study reported skin irritation in one patient in the intervention group. It was noted that this may have been from the investigational device and did not require additional treatment11. No other studies included in this analysis reported adverse reactions. However, previous studies have indicated that cyanoacrylate-based sealants may cause adverse events in paediatric patients, including cutaneous reactions11,15.

Resource use

Costs of antimicrobial sealants are a major resource concern, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. SSIs are associated with added morbidity, prolonged hospitalization by approximately 2 weeks and an increase in average health care costs of up to US$ 26 000 per patient16. Therefore, an intervention that is shown to consistently reduce SSI can reduce the cost of treating these infections. However, Lipp and colleagues found that no studies included in a meta-analysis reported the cost of cyanoacrylate sealants as a preoperative preparation of the surgical site and no benefit was shown in preventing SSI17.

Feasibility and equity

In addition to economic concerns related to cyanoacrylate sealant costs for preoperative use, the availability of these commercial products may be an added barrier in low- and middle-income countries. Furthermore, training in the proper technique for use would need to be available for surgical staff.

7. Key uncertainties and future research priorities

Several studies were excluded as they reported only bacterial colonization and not SSI as the primary outcome. Further studies are needed to identify evidence associated with important outcomes, including SSI rates (rather than microbial data), length of stay and cost-effectiveness.

Most of the included studies investigated the use of cyanoacrylate-based sealant in contaminated procedures and the use of these agents may be more or less effective in other procedures. Importantly, the protocol for standard surgical site preparation with antiseptics varied across studies, thus making it difficult to discern the actual effect of the sealant alone. Trials including a more diverse surgical patient population are needed. For example, more evidence is needed with paediatric surgical patients. Therefore, large, high quality RCTs reporting SSI as a primary outcome are required in the future to further investigate this issue.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search terms

Medline (through PubMed)

((“tissue adhesives”[Mesh] OR “fibrin tissue adhesive”[Mesh] OR “acrylates”[Mesh] OR “tissue adhesives” [TIAB] OR “tissue adhesive” [TIAB] OR (sealant*[TIAB] AND (microbial*[TIAB] OR fibrin [TIAB] OR antimicrobial* [TIAB] OR skin [TIAB])) OR Dermabond [TIAB] OR Integuseal [TIAB] OR acrylate* OR cyanoacrylate* OR octylcyanoacrylate* OR butylcyanoacrylate* OR bucrylate* OR enbucrilate* OR (sealing [TIAB] AND skin [TIAB]))) AND ((“surgical wound infection”[Mesh] OR surgical site infection* [TIAB] OR “SSI” OR “SSIs” OR surgical wound infection* [TIAB] OR surgical infection*[TIAB] OR post-operative wound infection* [TIAB] OR postoperative wound infection* [TIAB] OR wound infection*[TIAB]))

EMBASE

‘fibrin tissue adhesive’/exp OR ‘fibrin tissue adhesive’ OR ‘acrylates’/exp OR ‘acrylates’ OR ‘tissue adhesives’/exp OR ‘tissue adhesives’ OR ‘tissue adhesive’/exp OR ‘tissue adhesive’ OR (sealant* AND (microbial* OR ‘fibrin’/exp OR fibrin OR antimicrobial* OR ‘skin’/exp OR skin)) OR ‘dermabond’/exp OR dermabond OR ‘integuseal’/exp OR integuseal OR acrylate* OR cyanoacrylate* OR octylcyanoacrylate* OR butylcyanoacrylate* OR bucrylate* OR enbucrilate* OR (sealing AND (‘skin’/exp OR skin)) AND (‘surgical wound infection’/exp OR ‘surgical wound infection’ OR surgical AND site AND infection* OR ‘ssi’ OR ‘ssis’ OR surgical AND (‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection* OR surgical AND infection* OR ‘post operative’ AND (‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection* OR postoperative AND (‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection* OR ‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection* AND [embase]/lim AND [1990–2015]/py

CINAHL

‘fibrin tissue adhesive’/exp OR ‘fibrin tissue adhesive’ OR ‘acrylates’/exp OR ‘acrylates’ OR ‘tissue adhesives’/exp OR ‘tissue adhesives’ OR ‘tissue adhesive’/exp OR ‘tissue adhesive’ OR (sealant* AND (microbial* OR ‘fibrin’/exp OR fibrin OR antimicrobial* OR ‘skin’/exp OR skin)) OR ‘dermabond’/exp OR dermabond OR ‘integuseal’/exp OR integuseal OR acrylate* OR cyanoacrylate* OR octylcyanoacrylate* OR butylcyanoacrylate* OR bucrylate* OR enbucrilate* OR (sealing AND (‘skin’/exp OR skin)) AND (‘surgical wound infection’/exp OR ‘surgical wound infection’ OR surgical AND site AND infection* OR ‘ssi’ OR ‘ssis’ OR surgical AND (‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection* OR surgical AND infection* OR ‘post operative’ AND (‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection* OR postoperative AND (‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection* OR ‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection*

Cochrane CENTRAL

(wound infection or surgical wound infection) AND skin antisepsis

WHO Global Health Library

(ssi) OR (surgical site infection) OR (surgical site infections) OR (wound infection) OR (wound infections) OR (postoperative wound infection) AND (“skin preparation” OR “skin preparations” OR sealant)

- ti:

title;

- ab:

abstract

Appendix 3. Risk of bias assessment of the included studies

View in own window

| RCT, author, year | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Participants and personnel blinded | Outcome assessors blinded | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|

| Daeschlein, 201411 | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR |

| Doorly, 20158 | LOW | LOW | UNCLEAR | LOW | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | HIGH* |

| Dromzee, 20129 | LOW | LOW | LOW | UNCLEAR | LOW | HIGH | UNCLEAR* |

| Falk-Brynhildsen, 20144 | LOW | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW | UNCLEAR | HIGH* |

| Iyer, 20115 | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Towfigh, 200810 | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | UNCLEAR | LOW | UNCLEAR* |

| Vierhout, 20146 | LOW | LOW | HIGH | LOW | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW |

| Von Eckardstein, 20117 | LOW | LOW | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | HIGH* |

| Waldow, 201414** | HIGH1 | HIGH | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | HIGH* |

- *

Manufacturer of intervention provided product or funding for study.

- **

Quasi-randomized prospective trial.

RCT: randomized controlled trial.

References

- 1.

Mangram

AJ, Horan

TC, Pearson

ML, Silver

LC, Jarvis

WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:97–132; quiz 3–4; discussion 96. [

PubMed: 10196487]

- 2.

Dohmen

PM. Impact of antimicrobial skin sealants on surgical site infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2014;15:368–71. [

PubMed: 24818521]

- 3.

Higgins

JP, Altman

DG, Gotzsche

PC, Jüni

P, Moher

D, Oxman

AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration‘s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [

PMC free article: PMC3196245] [

PubMed: 22008217]

- 4.

The Nordic Cochrane Centre TCC. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

- 5.

GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool. Summary of findings tables, health technology assessment and guidelines. GRADE Working Group, Ontario: McMaster University and Evidence Prime Inc.; 2015 (

http://www.gradepro.org, accessed 5 May 2016).

- 6.

Daeschlein

G, Napp

M, Assadian

O, Bluhm

J, Krueger

C, von Poedwils

S, et al. Influence of preoperative skin sealing with cyanoacrylate on microbial contamination of surgical wounds following trauma surgery: a prospective, blinded, controlled observational study. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:274–8. [

PubMed: 25449258]

- 7.

Doorly

M, Choi

J, Floyd

A, Senagore

A. Microbial sealants do not decrease surgical site infection for clean-contaminated colorectal procedures. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:281–5. [

PubMed: 25772684]

- 8.

Dromzee

E, Tribot-Laspiere

Q, Bachy

M, Zakine

S, Mary

P, Vialle

R. Efficacy of integuseal for surgical skin preparation in children and adolescents undergoing scoliosis correction. Spine. 2012;37:E1331–5. [

PubMed: 22814302]

- 9.

Falk-Brynhildsen

K, Soderquist

B, Friberg

O, Nilsson

U. Bacterial growth and wound infection following saphenous vein harvesting in cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial of the impact of microbial skin sealant. Europ J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1981–7. [

PubMed: 24907853]

- 10.

Iyer

A, Gilfillan

I, Thakur

S, Sharma

S. Reduction of surgical site infection using a microbial sealant: a randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:438–42. [

PubMed: 21440263]

- 11.

Towfigh

S, Cheadle

WG, Lowry

SF, Malangoni

MA, Wilson

SE. Significant reduction in incidence of wound contamination by skin flora through use of microbial sealant. Arch Surg. 2008;143:885–91; discussion 91. [

PubMed: 18794427]

- 12.

Vierhout

BP, Ott

A, Reijnen

MM, Oskam

J, Ott

A, van den Dunggen

JJ, et al. Cyanoacrylate skin microsealant for preventing surgical site infection after vascular surgery: a discontinued randomized clinical trial. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2014;15:425–30. [

PubMed: 24840774]

- 13.

von Eckardstein

AS, Lim

CH, Dohmen

PM, Pêgo-Fernandez

PM, Cooper

WA, Oslund

SG, et al. A randomized trial of a skin sealant to reduce the risk of incision contamination in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:632–7. [

PubMed: 21704290]

- 14.

Waldow

T, Szlapka

M, Hensel

J, Plotze

K, Matschke

K, Jatzwauk

L. Skin sealant InteguSeal® has no impact on prevention of postoperative mediastinitis after cardiac surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2012;81:278–82. [

PubMed: 22705297]

- 15.

Roy

P, Loubiere

A, Vaillant

T, Edouard

B. [Serious adverse events after microbial sealant application in paediatric patients]. [Article in French] Ann Pharm Fr. 2014;72:409–14. [

PubMed: 25438651]

- 16.

de Lissovoy

G, Fraeman

K, Hutchins

V, Murphy

D, Song

D, Vaughn

BB. Surgical site infection: incidence and impact on hospital utilization and treatment costs. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:387–97. [

PubMed: 19398246]

- 17.

Lipp

A, Phillips

C, Harris

P, Dowie

I. Cyanoacrylate microbial sealants for skin preparation prior to surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD008062. [

PubMed: 23963766]