1. Introduction

Surgical site infections (SSI) are the result of multiple risk factors related to the patient, the surgeon and the health care environment. Microorganisms that cause SSI come from a variety of sources in the operating room environment, including the hands of the surgical team. Historically, surgical hand preparation (SHP) has been used to prevent SSI (1, 2).

The introduction of sterile gloves does not render SHP unnecessary. Sterile gloves contribute to preventing surgical site contamination and reduce the risk of bloodborne pathogen transmission from patients to the surgical team (3). However, 18% (range, 5–82%) of gloves have tiny punctures after surgery and more than 80% of cases go unnoticed by the surgeon (4). In addition, even unused gloves do not fully prevent bacterial hand contamination (5). Several reported outbreaks have been traced to contaminated hands from the surgical team, despite wearing sterile gloves (6–11). In contrast to hygienic handwash or handrub, SHP must eliminate the transient flora and reduce the resident flora (1). The aim of this preventive measure is to reduce the release of skin bacteria from the hands of the surgical team to the open wound for the duration of the procedure in case of an unnoticed puncture of the surgical glove (12).

The United Kingdom (UK)-based National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2008 guideline on SSI prevention recommends that the operating team should wash their hands prior to the first operation on the list using an aqueous antiseptic surgical solution and ensure that hands and nails are visibly clean with a single-use brush or pick for the nails,. Before subsequent operations, hands should be washed using either an alcohol-based handrub (ABHR) or an antiseptic surgical solution. If hands are visibly soiled, they should be washed again with an antiseptic surgical solution. A revised version of this guideline was published in 2013 and repeats the same SHP recommendation with the addition of ensuring the removal of any hand jewellery, artificial nails and nail polish before starting surgical hand decontamination (13, 14).

The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) practice recommendation guideline for preventing SSIs in acute care settings was updated in 2014 and suggests using an appropriate antiseptic agent to perform the preoperative surgical scrub. For most products, scrubbing of the hands and forearms was recommended to be performed for 2–5 minutes (15). However, none of the current guidelines is based on a systematic evaluatıon of the evidence.

A Cochrane systematic review was published in 2008 and very recently updated and published in 2016. The update included 14 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Four trials reported SSI rates as the primary outcome, while the remaining studies measured the numbers of colony-forming units (CFUs) on participants’ hands. The main finding was that that there is no firm evidence that one type of hand antisepsis (either ABHRs or aqueous scrubs) is better than another in reducing SSI, but the quality of the evidence was considered low to very low. However, moderate or very low quality evidence showed that ABHRs with additional antiseptic ingredients may be more effective to reduce CFUs compared with aqueous scrubs (16).

Given these controversial results, we decided to conduct a systematic review to identify any new evidence that would change these recommendations in terms of technique, duration and/or the product of choice.

2. PICO questions

What is the most effective type of product for SHP to prevent

SSI?

What is the most effective technique and the ideal duration for SHP?

3. Methods

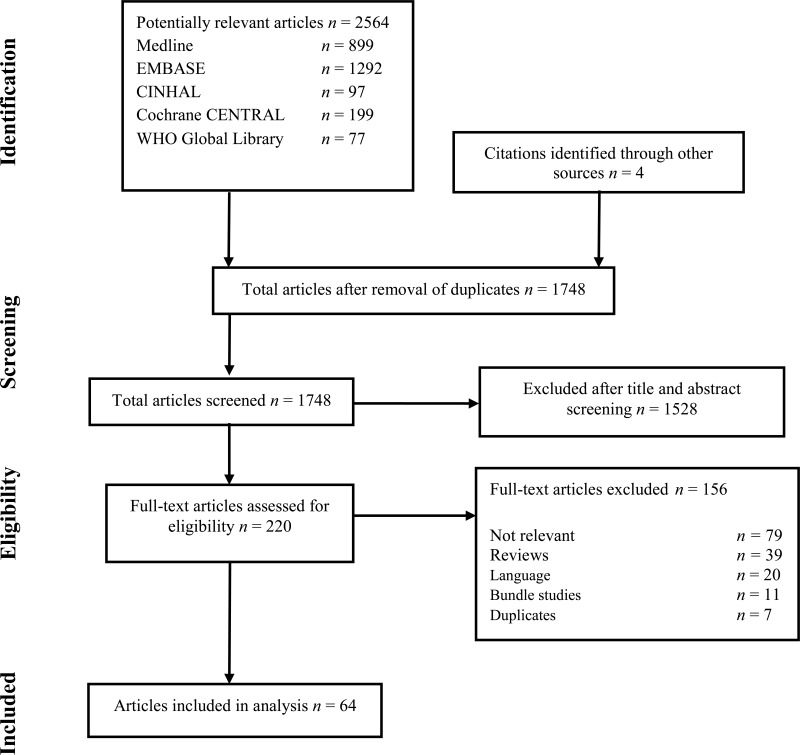

The following databases were searched: Medline (PubMed); Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Health Library. The time limit for the review was between 1 January 1990 and 24 April 2014. Language was restricted to English, French and Spanish. A comprehensive list of search terms was used, including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) (Appendix 1).

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved references for potentially relevant studies. The full text of all potentially eligible articles was obtained. Two authors independently reviewed the full text articles for eligibility based on inclusion criteria. Duplicate studies were excluded (Appendix 2).

Two authors extracted data in a predefined evidence table (Appendix 3A-D) and critically appraised the retrieved studies. Quality was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool to assess the risk of bias of RCTs (17) (Appendix 4). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or after consultation of the senior author, when necessary. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology (GRADE Pro software)(18) was used to assess the quality of the body of retrieved evidence (Appendix 5).

4. Study selection

Flow chart of the study selection process

5. Summary of the findings

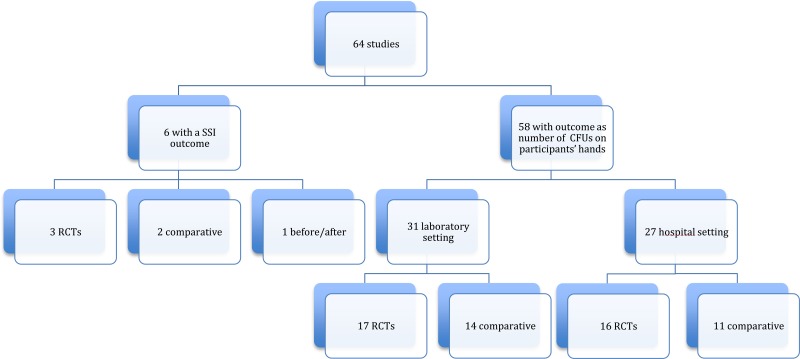

Among the 64 studies (Appendix 2) identified, there were only 6 studies (19–24) with SSI as the primary outcome, including 3 RCTs (19–21) and 3 observational (22–24) (one before-after study (23) and 2 comparative cohorts (22, 24)). All 6 studies compared handrubbing to hand scrubbing for SHP. Handrubbing was performed by using either Sterilium® (Bode Chemie GmbH, Hamburg-Stellingen, Germany; 75% aqueous alcohol solution containing propanol-1, propanol-2 and mecetronium), the WHO-recommended formulation II (75% (volume/volume [v/v]) isopropyl alcohol, 1.45% (v/v) glycerol, 0.125% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide), Avagard® (3M, Maplewood, MN, USA; 61% ethanol + 1% chlorhexidine gluconate [CHG] solution) or Purell® (Gojo Industries Inc., Akron, OH, USA; 62% ethyl alcohol as an active ingredient and water, aminomethyl propanol, isopropyl myristate, propylene glycol, glycerine, tocopheryl acetate, carbomer and fragrance as inactive ingredients). Hand scrubbing products containing either CHG or povidone-iodine (PVP-I) and/or plain soap. Five studies comparing ABHR to hand scrubbing with an antimicrobial soap containing either PVP-I 4% or CHG 4% showed no significant difference in SSI. The same result was found in a cluster, randomized, cross-over trial comparing ABHR to hand scrubbing with plain soap (20). It was not possible to perform any meta-analysis of these data as the products used for handrubbing and/or hand scrubbing were different. (Appendix 3A-3B).

The primary outcome in the remaining studies (58/64) was the number of CFUs on participants’ hands. The evaluation of this outcome demonstrated a great variety in terms of measurement (that is, log reduction, percentage or decrease in numbers) and/or different sampling techniques (that is, glove juice method or sampling the fingertips) and/or sampling times (that is, before and after surgery or at specific time points to evaluate the immediate and sustained effect). We identified 17 of 58 studies comparing handrub vs. hand scrub: 13 in a hospital setting and 4 in a laboratory setting. Only RCTs were included. Of a total of 8 RCTs, 6 were conducted in a hospital setting and 2 in a laboratory setting. Varying results were reported at different sampling times (that is immediate effect, sustained effect). Most studies in the hospital setting showed no significant difference, whereas the 2 RCTs in the laboratory setting showed that handrubbing was more effective than hand scrubbing in reducing the number of CFUs on participants’ hands (Appendix 3C).

The only comparison we were able to make was to investigate the efficacy of a shorter duration of application than usually recommended when the same formulation and technique were used. Twelve studies addressed this question: 3 in the hospital setting and 9 in the laboratory setting. Only RCTs were included. Of a total of 5 RCTs (one in a hospital setting and 4 in a laboratory setting), all reported varying results. Although all studies used an ABHR, the product formulations differed, including the alcohol percentages (Appendix 4D). There were only 2 RCTs (one in the hospital setting and one in the laboratory setting) comparing exactly the same formulation (Sterilium®). Both studies showed an equivalence of 1.5 minutes to 3 minutes in decreasing CFUs on participants’ hands (Appendix 3D).

As the product concentrations differed across the studies, a meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of their duration could not be performed due to substantial heterogeneity and no conclusion could be drawn from these findings. There were only 2 RCTs comparing exactly the same formulations, but they were performed in different settings (one in the laboratory and the one in the hospital setting). Given the variability of the products, sampling techniques, settings and/or outcome measures, none of the identified studies was eligible for meta-analysis.

In conclusion, evidence from RCTs with an SSI outcome only was taken into account for this systematic review and was rated as moderate due to inconsistency. The overall evidence shows no difference between handrubbing and hand scrubbing in reducing SSI.

However, there are a number of limitations related to these studies. Although the systematic review also identified 58 studies conducted either in laboratory or hospital settings and evaluating participants’ hand microbial colonization following SHP with different products and techniques, there was a high variability in the study setting, microbiological methods used, type of product and time of sampling. The authors decided not to take this indirect evidence into consideration when formulating the recommendation.

6. Other factors considered in the review

The systematic review team identified the following other factors to be considered.

Values and preferences

No study was found on patient values and preferences with regards to this intervention. Given that SHP is considered as best clinical practice since almost 200 years and is recommended in all surgical guidelines, the Guidelines Development Group is confident that the typical values and preferences of the target population would favour the intervention.

Studies of surgeon preferences indicate a primary preference for ABHRs. Most studies show that ABHRs are better tolerated and more acceptable to surgeons than hand scrubbing, mainly due to the decrease in time required for SHP and less skin reactions. The included studies provided some data on the acceptability and tolerability of the formulations. According to a user survey in a study conducted in Kenya (20), operating room staff showed a preference for ABHR as it was quicker to use, independent of the water supply and quality and did not require drying hands with towels. No skin reactions were reported with either ABHR or plain soap and water. Parienti and colleagues (19) assessed 77 operating room staff for skin tolerance and found that skin dryness and irritation was significantly better in the handrubbing periods of the study. Although Al-Naami and colleagues (21) failed to show a significant difference, a survey of operating room staff in a Canadian SHP intervention study (23) showed that 97% of responders approved of the switch to handrubbing and 4 persons even noted an improvement in their skin condition. All studies reported fewer (one or none) cases of substantial dermatitis with ABHR compared to hand scrubbing. In one study, some surgeons noted occasional reversible bleaching of the forearm hair after the repeated use of handrub (20).

Resource implications

Observational studies with SSI outcome showed a significant cost benefit of handrubbing. A Canadian study (23) showed that the standard hand scrub-related costs of direct supplies were evaluated to be approximately Can$ 6000 per year for 2000 surgical procedures, not including the cost of cleaning and sterilizing surgical towels. The actual expenses incurred after a full year of handrub use were Can$ 2531 for an annual saving of approximately Can$ 3500. A dramatic decrease in surgical towel usage (an average of 300 fewer towels per week or 1200 per period) added to the savings. Two other studies (22, 24) from the United States of America and the Côte d’Ivoire showed lower costs with Avagard® and Sterilium® when compared to using antiseptic-impregnated hand brushes and a PVP-I product, respectively. One of the RCTs (20) included in this review also supported these findings and showed that the approximate total weekly cost of a locally-produced ABHR according to the modified WHO formula was even cheaper than plain soap and water (€ 4.60 compared to € 3.30; cost ratio 1:1.4).

Despite this evidence of the cost-effectiveness of ABHRs, they may still be very expensive with limited availability in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), even if local production is promoted. The barriers to local production include the difficulty to identify staff with adequate skills, the need for staff training, constraints related to ingredient and dispenser procurement and a lack of adequate quality control. However, the Guidelines Development Group strongly emphasized that local production is a promising option in these circumstances. A WHO survey (25) in 39 health facilities from 29 countries demonstrated that the WHO ABHR formulations can be easily produced locally at low cost and are very well tolerated and accepted by health care workers. The contamination of alcohol-based solutions has seldom been reported, but the GDG highlighted the concern that top-up dispensers, which are more readily available, impose a risk for microbial contamination, particularly in LMICs. According to the WHO survey, the reuse of dispensers at several sites helped overcome difficulties caused by local shortages and the relatively high costs of new dispensers. However, such reuse may lead to handrub contamination, especially when empty dispensers are reprocessed by simple washing before being refilled. In addition, the “empty, clean, dry, then refill” strategy to avoid this risk may require extra resources.

The feasibility and costs related to the standard quality control of locally-produced products is another consideration. In the WHO survey (25), 11 of 24 sites were unable to perform quality control locally due to the lack of equipment and costs. However, most sites were able to perform basic quality control with locally-purchased alcoholmeters.

The use of soap and water will require disposable towels, which add to the cost. Cloth towel reuse is not recommended in the health care setting and towels should be changed between health care workers, if necessary, thus resulting in resource implications.

7. Key uncertainties and future research priorities

The Guidelines Development Group noted that there are major research gaps and heterogeneity in the literature regarding comparisons of product efficacy and the technique and duration of scrubbing methods with SSI as the primary outcome. In particular, it would be useful to conduct RCTs in the clinical setting to compare the effectiveness of various antiseptic products with sustained activity to reduce SSI vs. ABHR or antimicrobial soap with no sustained effect. Furthermore, well-designed studies on cost-effectiveness and the tolerability/acceptability of locally-produced formulations in LMICs would be helpful. Further research is also needed to assess the interaction between products used for SHP and the different types of surgical gloves in relation to SSI outcome.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Medline (via PubMed)

- #1.

“surgical wound infection”[Mesh] OR (surgical site infection* [TIAB] OR “SSI” OR “SSIs” OR surgical wound infection* [TIAB] OR surgical infection*[TIAB] OR post-operative wound infection* [TIAB] OR postoperative wound infection* [TIAB] OR wound infection*[TIAB])

- #2.

“hand hygiene”[MeSH] OR “hand hygiene” OR “hand washing” OR handwashing OR” hand rubbing” OR handrubbing OR “hand disinfection”[Mesh] OR “hand disinfection” OR “hand antisepsis” OR “scrubbing” OR scrub OR “hand preparation” OR “alcohol-based hand rub” OR “alcohol-based handrub” OR ((“povidone-iodine”[Mesh] OR povidone OR “iodophors”[Mesh] OR iodophor OR iodophors OR “iodine”[Mesh] OR iodine OR betadine OR “triclosan”[Mesh] OR triclosan OR “chlorhexidine”[Mesh] OR chlorhexidine OR hibiscrub OR hibisol OR alcohol OR alcohols OR gel OR “soaps”[Mesh] OR soap [TIAB] OR soaps [TIAB]) AND hand AND (disinfectants OR “antisepsis”[Mesh] OR antisepsis OR antiseptics OR detergents))

- #3.

Step 1 AND Step 2

- #4.

(“surgical procedures, operative”[Mesh] OR surgery OR surgical)

- #5.

“time factors”[Mesh] OR duration OR “treatment outcome”[Mesh] OR technique OR “colony count, microbial”[Mesh] or colonization [TIAB] OR transmission [TIAB] OR contamination [TIAB]

- #6.

Step 4 AND Step 2 AND Step 5

- #7.

Step 3 OR Step 6

EMBASE

- #1.

‘surgical infection’/exp OR ‘surgical site infection’:ti,ab OR ‘surgical site infections’:ti,ab OR ssis OR ‘surgical infection wound’:ti,ab OR ‘surgical infection wounds’:ti,ab OR ‘surgical infection’:ti,ab OR ‘postoperative wound infection’:ti,ab OR ‘postoperative wound infections’:ti,ab OR ‘post-operative wound infection’:ti,ab OR ‘post-operative wound infections’:ti,ab OR ‘wound infection’:ti,ab OR ‘wound infections’:ti,ab

- #2.

‘hand washing’/exp OR ‘hand hygiene’ OR ‘hand washing’ OR ‘handwashing’ OR ‘hand rubbing’ OR ‘handrubbing’ OR ‘hand disinfection’ OR ‘hand antisepsis’ OR ‘scrubbing’ OR ‘scrub’ OR ‘hand preparation’ OR ‘alcohol based hand rub’ OR ‘alcohol based handrub’ OR ((‘povidone iodine’/exp OR povidone OR ‘iodophor’/exp OR iodophor OR iodophors OR ‘iodine’/exp OR iodine OR betadine OR ‘triclosan’/exp OR triclosan OR ‘chlorhexidine’/exp OR chlorhexidine OR hibiscrub OR hibisol OR alcohol OR alcohols OR gel OR ‘soap’/exp OR soap*:ti,ab) AND hand AND (disinfectants OR ‘antisepsis’/exp OR antisepsis OR antiseptics OR detergents))

- #3.

‘surgery’/exp OR surgery;ti,ab OR surgical:ti,ab

- #4.

‘time’/exp OR duration OR ‘treatment outcome’/exp OR technique:ti,ab OR ‘bacterial count’/exp OR colonization:ti,ab OR colonisation:ti,ab OR transmission:ti,ab OR contamination:ti,ab

- #5.

#2 AND #3 AND #4

- #6.

#1 AND #2

- #7.

#5 OR #6

CINAHL

- #1.

(MH surgical wound infection) OR (AB surgical site infection* OR AB SSI OR AB SSIs OR AB surgical wound infection* OR AB surgical infection* OR AB postoperative wound infection* OR AB postoperative wound infection* OR AB wound infection*)

- #2.

(MH handwashing+) OR AB hand hygiene OR AB hand washing OR AB handwashing OR AB hand rubbing OR AB handrubbing OR AB disinfection OR AB antisepsis OR AB scrubbing OR AB scrub OR AB hand preparation OR AB alcohol-based hand rub OR AB alcohol-based handrub OR (((MH povidone-iodine) OR AB povidone OR (MH iodophors) OR AB iodophor OR AB iodophors OR (MH iodine) OR AB iodine OR AB betadine OR (MH triclosan) OR AB triclosan OR (MH chlorhexidine) OR AB chlorhexidine OR AB hibiscrub OR AB hibisol OR AB alcohol OR AB alcohols OR AB Gel OR (MH soaps) OR AB soap OR AB soaps) AND AB hand AND (AB disinfectants OR (MH antiinfective agents+) OR AB antisepsis OR AB antiseptics OR AB detergents))

- #3.

Step 1 AND Step 2

- #4.

(MH surgery, operative+) OR AB surgery OR AB surgical)

- #5.

(MH time factors) OR AB duration OR (MH treatment outcomes+) OR AB technique OR (MH colony count, microbial) or AB colonization OR AB transmission OR AB contamination

- #6.

Step 4 AND Step 2 AND Step 5

- #7.

Step 3 OR Step 6

Cochrane CENTRAL

- #1.

MeSH descriptor: [surgical wound infection] explode all trees

- #2.

surgical site infections or SSI or SSIs or surgical wound infection* or surgical infection* or post-operative wound infection* or postoperative wound infection* or wound infection*:ti,ab,kw (word variations have been searched)

- #3.

#1 or #2

- #4.

MeSH descriptor: [hand hygiene] explode all trees

- #5.

hand hygiene or hand washing or handwashing or hand rubbing or handrubbing or hand disinfection or hand antisepsis or scrub* or hand preparation or alcohol-based hand rub or alcohol-based handrub:ti,ab,kw (word variations have been searched

- #6.

#4 or #5

- #7.

MeSH descriptor: [povidone-iodine] explode all trees

- #8.

MeSH descriptor: [iodine] explode all trees

- #9.

MeSH descriptor: [iodophors] explode all trees

- #10.

MeSH descriptor: [chlorhexidine] explode all trees

- #11.

MeSH descriptor: [alcohols] explode all trees

- #12.

MeSH descriptor: [soaps] explode all trees

- #13.

MeSH descriptor: [triclosan] explode all trees

- #14.

povidone or iodophor or iodophors or iodine or betadine or triclosan or chlorhexidine or hibiscrub or hibisol or alcohol or alcohols or gel or soap or soaps:ti,ab,kw (word variations have been searched)

- #15.

MeSH descriptor: [detergents] explode all trees

- #16.

#7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15

- #17.

hand:ti,ab,kw

- #18.

MeSH descriptor: [disinfectants] explode all trees

- #19.

MeSH descriptor: [antisepsis] explode all trees

- #20.

disinfect* or antisepsis or antiseptic* or detergent*:ti,ab,kw (word variations have been searched)

- #21.

#18 or #19 or #20

- #22.

#16 and #17 and #21

- #23.

#6 or #22

- #24.

#3 and #23

- #25.

MeSH descriptor: [general surgery] explode all trees

- #26.

surgery or surgical:ti,ab,kw (word variations have been searched)

- #27.

#25 or #26

- #28.

MeSH descriptor: [colony count, microbial] explode all trees

- #29.

MeSH descriptor: [time factors] explode all trees

- #30.

MeSH descriptor: [treatment uutcome] explode all trees

- #31.

duration or technique or colonization or transmission or contamination:ti,ab,kw (word variations have been searched)

- #32.

#28 or #29 or #30 or #31

- #33.

#23 and #27 and #32

- #34.

#24 or #33

WHO Global Health Library

((ssi) OR (surgical site infection) OR (surgical site infections) OR (wound infection) OR (wound infections)) AND ((hand) OR (scrub) OR (scrubbing))

- ti:

title;

- ab:

abstract;

Appendix 2. Distribution of the selected studies

Appendix 3. Evidence table

3B. Observational studies with SSI outcome

Download PDF (114K)

3C. RCTs: handrub vs. hand scrub with the number of CFUs on participants’ hands as outcome

Download PDF (136K)

3D. RCTs comparing different application times with the number of CFUs on participants’ hands as outcome

Download PDF (113K)

Appendix 4. Risk of bias assessment

View in own window

| Author, year, reference | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Participants blinded* | Care providers blinded | Outcome assessors blinded | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|

| RCTs comparing handrubbing vs. hand scrubbing with SSI outcome |

|---|

| Parienti 2002(19) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Nthumba 2010(20) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| Al-Naami 2009(21) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | - |

| RCTs comparing an application of 1.5 minute vs. 3 minutes of the same ABHR with the number of CFUs on participants’ hands as outcome |

|---|

| Weber 2009(34) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | N/A | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | ** |

| Suchomel 2009(35) | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | N/A | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | ** |

- *

Blinding participants is impossible in these studies as the intervention and comparator are significantly different in nature (that is, ABHR vs. soap or PVP-I or CHG and different durations of the same ABHR)

- **

Potential reporting bias was suspected as both studies tested Sterilium®, which was the commercially available product at the time. However; they clearly state a conflict of interest in the studies. First (Weber), was funded partially by the University of Basel and Bode Chemie, but they clearly state that industry had no role in any aspect of the study, and the second (Suchomel) was not funded at all. Of note, neither of the studies are a superiority trial as they tested the efficacy of different durations of the same product. Therefore, reporting bias is highly unlikely.

RCT: randomized controlled trial; SSI: surgical site outcome; PVP-I: povidone-iodine; CHG: chlorhexidine gluconate; ABHR: alcohol-based hand rub; CFU: colony-forming units; N/A: not applicable.

References

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

Beltrami

EM, Williams

IT, Shapiro

CN, Chamberland

ME. Risk and management of blood-borne infections in health care workers. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(3):385–407. [

PMC free article: PMC88939] [

PubMed: 10885983]

- 4.

Thomas

S, Agarwal

M, Mehta

G. Intraoperative glove perforation--single versus double gloving in protection against skin contamination. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77(909):458–60. [

PMC free article: PMC1760980] [

PubMed: 11423598]

- 5.

Doebbeling

BN, Pfaller

MA, Houston

AK, Wenzel

RP. Removal of nosocomial pathogens from the contaminated glove. Implications for glove reuse and handwashing. Ann Int Med. 1988;109(5):394–8. [

PubMed: 3136685]

- 6.

Lark

RL, Van der Hyde

K, Deeb

GM, Dietrich

S, Massey

JP, Chenoweth

C. An outbreak of coagulase-negative staphylococcal surgical-site infections following aortic valve replacement. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(10):618–23. [

PubMed: 11776347]

- 7.

McNeil

SA, Foster

CL, Hedderwick

SA, Kauffman

CA. Effect of hand cleansing with antimicrobial soap or alcohol-based gel on microbial colonization of artificial fingernails worn by health care workers. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2001;32(3):367–72. [

PubMed: 11170943]

- 8.

Grohskopf

LA, Roth

VR, Feikin

DR, Arduino

MJ, Carson

LA, Tokars

JI, et al. Serratia liquefaciens bloodstream infections from contamination of epoetin alfa at a hemodialysis center. New Engl J Med. 2001;344(20):1491–7. [

PubMed: 11357151]

- 9.

Weber

S, Herwaldt

LA, Mcnutt

LA, Rhomberg

P, Vaudaux

P, Pfaller

MA, et al. An outbreak of

Staphylococcus aureus in a pediatric cardiothoracic surgery unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23(2):77–81. [

PubMed: 11893152]

- 10.

Koiwai

EK, Nahas

HC. Subacute bacterial endocarditis following cardiac surgery. AMA Arch Surg. 1956;73(2):272–8. [

PubMed: 13354123]

- 11.

Mermel

LA, McKay

M, Dempsey

J, Parenteau

S.

Pseudomonas surgical-site infections linked to a healthcare worker with onychomycosis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24(10):749–52. [

PubMed: 14587936]

- 12.

Kampf

G, Goroncy-Bermes

P, Fraise

A, Rotter

M. Terminology in surgical hand disinfection--a new Tower of Babel in infection control. J Hosp Infect. 2005;59(3):269–71. [

PubMed: 15694992]

- 13.

Leaper

D, Burman-Roy

S, Palanca

A, Cullen

K, Worster

D, Gautam-Aitken

E, et al. Prevention and treatment of surgical site infection: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1924. [

PubMed: 18957455]

- 14.

- 15.

Anderson

DJ, Podgorny

K, Berrios-Torres

SI, Bratzler

DW, Dellinger

EP, Greene

L, et al. Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(6):605–27. [

PMC free article: PMC4267723] [

PubMed: 24799638]

- 16.

- 17.

Higgins

JP, Altman

DG, Gotzsche

PC, Jüni

P, Moher

D, Oxman

AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration‘s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [

PMC free article: PMC3196245] [

PubMed: 22008217]

- 18.

GRADEpro. Guideline Development Tool. Summary of findings tables, health technology assessment and guidelines. GRADE Working Group, Ontario: McMaster University and Evidence Prime Inc.; 2015 (

http://www.gradepro.org, accessed 5 May 2016).

- 19.

Parienti

JJ, Thibon

P, Heller

R, Le Roux

Y, Von Theobald

P, Bensadoun

H, et al. Hand-rubbing with an aqueous alcoholic solution vs traditional surgical hand-scrubbing and 30-day surgical site infection rates: A randomized equivalence study. JAMA. 2002;288(6):722–7. [

PubMed: 12169076]

- 20.

Nthumba

PM, Stepita-Poenaru

E, Poenaru

D, Bird

P, Allegranzi

B, Pittet

D, et al. Cluster-randomized, crossover trial of the efficacy of plain soap and water versus alcohol-based rub for surgical hand preparation in a rural hospital in Kenya. Br J Surg. 2010; (11):1621–8. [

PubMed: 20878941]

- 21.

Al-Naami

MY, Anjum

MN, Afzal

MF, Al-Yami

MS, Al-Qahtani

SM, Al-Dohayan

AD, et al. Alcohol-based hand-rub versus traditional surgical scrub and the risk of surgical site infection: a randomized controlled equivalent trial. EWMA J. 2009; 9(3):5–10.

- 22.

Weight

CJ, Lee

MC, Palmer

JS. Avagard hand antisepsis vs. traditional scrub in 3600 pediatric urologic procedures. Urology. 2010;76(1):15–7. [

PubMed: 20363495]

- 23.

Marchand

R, Theoret

S, Dion

D, Pellerin

M. Clinical implementation of a scrubless chlorhexidine/ethanol pre-operative surgical hand rub. Can Oper Room Nurs J. 2008;26(2):21–2, 6, 9–2231. [

PubMed: 18678198]

- 24.

Adjoussou

S, Konan Ble

R, Seni

K, Fanny

M, Toure-Ecra

A, Koffi

A, et al. Value of hand disinfection by rubbing with alcohol prior to surgery in a tropical setting. Med Trop. 2009;69(5):463–6. [

PubMed: 20025174]

- 25.

Bauer-Savage

J, Pittet

D, Kim

E, Allegranzi

B. Local production of WHO-recommended alcohol-based handrubs: feasibility, advantages, barriers and costs. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:963–9. [

PMC free article: PMC3845264] [

PubMed: 24347736]

- 26.

Gupta

C, Czubatyj

AM, Briski

LE, Malani

AK. Comparison of two alcohol-based surgical scrub solutions with an iodine-based scrub brush for presurgical antiseptic effectiveness in a community hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65(1):65–71. [

PubMed: 16979793]

- 27.

- 28.

Larson

EL, Aiello

AE, Heilman

JM, Lyle

CT, Cronquist

A, Stahl

JB, et al. Comparison of different regimens for surgical hand preparation. AORN J. 2001;73(2):412–4. [

PubMed: 11218929]

- 29.

Ghorbani

A, Shahrokhi

A, Soltani

Z, Molapour

A, Shafikhani

M. Comparison of surgical hand scrub and alcohol surgical hand rub on reducing hand microbial burden. J Perioper Pract. 2012;22(2):67–70. [

PubMed: 22724306]

- 30.

Chen

CF, Han

CL, Kan

CP, Chen

SG, Hung

PW. Effect of surgical site infections with waterless and traditional hand scrubbing protocols on bacterial growth. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(4):e15-e7. [

PubMed: 22305412]

- 31.

Pietsch

H. Hand antiseptics: Rubs versus scrubs, alcoholic solutions versus alcoholic gels. J Hosp Infect. 2001;(Suppl):S33–6. [

PubMed: 11759022]

- 32.

Rotter

M, Kundi

M, Suchomel

M, Harke

HP, Kramer

A, Ostermeyer

C, et al. Reproducibility and workability of the European test standard EN 12791 regarding the effectiveness of surgical hand antiseptics: a randomized, multicenter trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27(9):935–9. [

PubMed: 16941319]

- 33.

Mulberrry

G, Snyder

AT, Heilman

J, Pyrek

J, Stahl

J. Evaluation of a waterless, scrubless chlorhexidine gluconate/ethanol surgical scrub for antimicrobial efficacy. Am J Infect Control. 2001;29(6):377–82. [

PubMed: 11743484]

- 34.

Weber

WP, Reck

S, Neff

U, Saccilotto

R, Dangel

M, Rotter

ML, et al. Surgical hand antisepsis with alcohol-based hand rub: comparison of effectiveness after 1.5 and 3 minutes of application. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(5):420–6. [

PubMed: 19320574]

- 35.

Suchomel

M, Gnant

G, Weinlich

M, Rotter

M. Surgical hand disinfection using alcohol: the effects of alcohol type, mode and duration of application. J Hosp Infect. 2009;71(3):228–33. [

PubMed: 19144448]

- 36.

Suchomel

M, Koller

W, Kundi

M, Rotter

ML. Surgical hand rub: influence of duration of application on the immediate and 3-hours effects of n-propanol and isopropanol. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37(4):289–93. [

PubMed: 19188002]

- 37.

Suchomel

M, Rotter

M. Ethanol in pre-surgical hand rubs: concentration and duration of application for achieving European Norm EN 12791. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77(3):263–6. [

PubMed: 21190755]

- 38.

Babb

JR, Davies

JG, Ayliffe

GA. A test procedure for evaluating surgical hand disinfection. J Hosp Infect. 1991;18(Suppl. B):41–9. [

PubMed: 1679446]