All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: tni.ohw@sredrokoob). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html).

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children: Guidelines for the Management of Common Childhood Illnesses. 2nd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children: Guidelines for the Management of Common Childhood Illnesses. 2nd edition.

Show detailsIn general, the management of specific conditions in HIV-infected children is similar to that in other children (see Chapters 3–7). Most infections in HIV-positive children are caused by the same pathogens as in HIV-negative children, although they may be more frequent, more severe and occur repeatedly. Some, infections, however, are due to unusual pathogens.

Many HIV-positive children die from common childhood illnesses, and some of these deaths are preventable by early diagnosis and correct management or by giving routine scheduled vaccinations and improving nutrition. These children have a particularly greater risk for staphylococcal and pneumococcal infections and TB. Saving children's lives depends on early identification, immediate treatment with ART and co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for those who are HIV-infected.

All infants and children should have their HIV status established at their first contact with the health system, ideally at birth or at the earliest opportunity thereafter. To facilitate this, all areas of the hospital in which maternal, neonatal and child services are delivered should offer HIV serological testing to mothers and their infants and children.

This chapter covers mainly the management of children with HIV/AIDS: diagnosis of HIV infection, counselling and testing, clinical staging, ART, management of HIV-related conditions, supportive care, breastfeeding, planning discharge and follow-up and palliative care for terminally ill children.

8.1. Sick child with suspected or confirmed HIV infection

8.1.1. Clinical diagnosis

The clinical expression of HIV infection in children is highly variable. Many HIV-positive children show severe HIV-related signs and symptoms in the first year of life, while others may remain asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic for more than a year and may survive for several years.

Clinical experience indicates that children infected with HIV perinatally who are not on antiretroviral therapy fit into one of three categories:

- those with rapid progression (25–30%), most of whom die before their first birthday; they are thought to have acquired the infection in utero or during the early postnatal period;

- children who develop symptoms early in life, then follow a downhill course and die at the age of 3–5 years (50–60%);

- long-term survivors, who live beyond 8 years of age (5–25%); they tend to have lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis and stunting, with low weight and height for age.

Suspect HIV if any of the following signs, which are not common in HIV-negative children, are present:

Signs that may indicate possible HIV infection

- recurrent infection: three or more severe episodes of a bacterial infection (such as pneumonia, meningitis, sepsis, cellulitis) in the past 12 months

- oral thrush: erythema and white-beige pseudomembranous plaques on the palate, gums and buccal mucosa. After the neonatal period, the presence of oral thrush is highly suggestive of HIV infection when it lasts > 30 days despite antibiotic treatment, recurs, extends beyond the tongue or presents as oesophageal candidiasis.

- chronic parotitis: unilateral or bilateral parotid swelling (just in front of the ear) for ≥ 14 days, with or without associated pain or fever.

- generalized lymphadenopathy: enlarged lymph nodes in two or more extrainguinal regions with no apparent underlying cause.

- hepatomegaly with no apparent cause: in the absence of concurrent viral infections such as cytomegalovirus.

- persistent and/or recurrent fever: fever (> 38 °C) lasting ≥ 7 days or occurring more than once over 7 days.

- neurological dysfunction: progressive neurological impairment, microcephaly, delay in achieving developmental milestones, hypertonia or mental confusion

- herpes zoster (shingles): painful rash with blisters confined to one dermatome on one side

- HIV dermatitis: erythematous papular rash. Typical skin rashes include extensive fungal infections of the skin, nails and scalp and extensive molluscum contagiosum.

- chronic suppurative lung disease

Signs or conditions specific to HIV-infected children

Strongly suspect HIV infection if the following are present:

- Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly carinii) pneumonia (PCP)

- oesophageal candidiasis

- lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia

- Kaposi sarcoma

- acquired recto-vaginal fistula (in girls)

Signs common in HIV-infected children but which also occur in ill children with no HIV infection

- chronic otitis media: ear discharge lasting ≥ 14 days

- persistent diarrhoea: diarrhoea lasting ≥ 14 days

- moderate or severe acute malnutrition: weight loss or a gradual but steady deterioration in weight gain from that expected, as indicated on the child's growth card. Suspect HIV particularly in breastfed infants < 6 months old who fail to thrive.

8.1.2. HIV counselling

HIV provider-initiated testing and counselling should be offered to all children attending clinical services in countries with generalized HIV epidemics (prevalence over 1% in pregnant women). If the child's HIV status is not known, counsel the family and offer diagnostic testing for HIV.

As the majority of children are infected by vertical transmission from the mother, the mother and often the father are probably infected but may not know it. Even in countries with a high prevalence of HIV infection, it remains an extremely stigmatizing condition, and the parents may feel reluctant to undergo testing.

In HIV counselling, the child should be treated as part of the family by taking into account the psychological implications of HIV for the child, mother, father and other family members. Counsellors should stress that, although there is no definitive cure, early initiation of ART and supportive care can greatly improve the child's and the parents' quality of life and survival.

Counselling requires time and must be done by trained staff. If there are no trained staff, assistance should be sought from local AIDS support organizations. HIV testing should be voluntary, with no coercion, and informed consent should be obtained before testing is performed.

Indications for HIV counselling and testing

All infants and children in countries with generalized HIV epidemics with unknown HIV status should be offered counselling and testing. In most cases, the HIV status of the child is established by asking about maternal HIV testing during pregnancy, labour or postpartum and checking the child's or mother's health card. If the HIV status is not known, counselling and testing should be offered in the following situations to:

- all infants and children in generalized HIV epidemic settings (prevalence > 1% in pregnant women).

- all HIV-exposed infants at birth or at the earliest opportunity thereafter.

- any infant or child presenting with signs, symptoms or medical conditions that could indicate HIV infection.

- all pregnant women and their partners in generalized HIV epidemics.

8.1.3. Testing and diagnosis of HIV infection

Diagnosis of HIV infection in perinatally exposed infants and young children < 18 months of age is difficult, because passively acquired maternal HIV antibodies may still be present in the child's blood. Additional diagnostic challenges arise if the child is still breastfeeding or has been breastfed. Although many children will have lost HIV antibodies between 9 and 18 months, a virological test is the only reliable method for determining the HIV status of a child < 18 months of age.

When either the mother or the child has a positive serological HIV test and the child has specific symptoms suggestive of HIV infection but virological testing is not available, the child may presumptively be diagnosed as having HIV infection. However, HIV virological testing should be done at the earliest opportunity to confirm infection.

All diagnostic HIV testing of children must be confidential, be accompanied by counselling and conducted only with informed consent, so that it is both informed and voluntary.

HIV serological antibody test (ELISA or rapid tests)

Rapid tests are widely available, sensitive and reliable for diagnosing HIV infection in children > 18 months. For children < 18 months, HIV antibody tests are a sensitive, reliable way of detecting exposure and of excluding HIV infection in non-breastfeeding children.

Rapid HIV tests can be used to exclude HIV infection in a child presenting with severe acute malnutrition, or TB or any other serious clinical event in areas of high HIV prevalence. For children aged < 18 months, confirm all positive HIV serological results by virological testing as soon as possible (see below). When this is not possible, repeat antibody testing at 18 months.

Virological tests

Virological testing for HIV-specific RNA or DNA is the most reliable method for diagnosing HIV infection in children < 18 months of age. This may require sending a blood sample to a specialized laboratory that can perform this test, although virological testing is becoming more widely available in many countries. The tests are relatively cheap, easy to standardize and can be done on dried blood spots. The following assays (and respective specimen types) may be available:

- HIV DNA on whole blood specimen or dried blood spots

- HIV RNA on plasma or dried blood spots

- ultrasensitive p24 antigen detection in plasma or dried blood spots

One positive virological test at 4–8 weeks is sufficient to diagnose HIV infection in a young infant. ART should be started without delay, and, at the same time, a second specimen should be collected to confirm the positive virological test result.

If the infant is still breastfeeding and the virological test is negative, it should be repeated 6 weeks after complete cessation of breastfeeding to confirm that the child is not infected with HIV.

The results of virological testing in infants should be returned to the clinic and to the child, mother or carer as soon as possible but at the very latest within 4 weeks of specimen collection.

Diagnosing HIV infection in breastfeeding infants

A breastfeeding infant is at risk of acquiring HIV infection from an infected mother throughout the period of breastfeeding. Breastfeeding should not be stopped in order to perform diagnostic HIV viral testing. Positive test results should be considered to reflect HIV infection. The interpretation of negative results is, however, difficult because a 6-week period after complete cessation of breastfeeding is required before negative viral test results can reliably indicate HIV infection status.

8.1.4. Clinical staging

In a child with diagnosed or highly suspected HIV infection, the clinical staging system helps to determine the degree of damage to the immune system and to plan treatment and care.

The clinical stages represent a progressive sequence from least to most severe, each higher clinical stage indicating a poorer prognosis. Initiating ART, with good adherence, dramatically improves the prognosis. Clinical staging events can be used to identify the response to ART if there is no easy access to tests for viral load or CD4 count.

Table 23WHO paediatric clinical staging system for HIV infection

| For use in children aged < 13 years with confirmed laboratory evidence of HIV infection (HIV antibodies for children > 18 months, virological testing for those aged < 18 months) |

| STAGE 1 |

|---|

|

| STAGE 2 |

|

| STAGE 3 |

|

| STAGE 4 |

|

- a

TB may occur at any CD4 count; the percentage CD4 should be considered when available.

- b

Presumptive diagnosis of stage 4 disease in seropositive children < 18 months requires confirmation with HIV virological tests or an HIV antibody test after 18 months of age.

8.2. Antiretroviral therapy

All HIV-infected infants < 60 months of age should immediately begin ART once diagnosed with HIV infection, regardless of clinical or immunological status. Although antiretroviral drugs cannot cure HIV infection, they dramatically reduce mortality and morbidity and improve the children's quality of life.

The current standard first-line treatment for HIV infection is use of three antiretroviral medications (triple drug therapy) to suppress viral replication as much as possible and thus arrest the progression of HIV disease. Fixed-dose combinations are now available and are preferable to syrups or single drugs because they encourage adherence to treatment, and reduce the cost.

Clinicians should be familiar with the national paediatric HIV treatment guidelines. The underlying principles of ART and the choice of first-line drugs for children are largely the same as for adults. Suitable formulations for children may not be available for some antiretroviral drugs (particularly the protease inhibitor class). It is nevertheless important to consider:

- the availability of a suitable formulation that can be taken in appropriate doses

- the simplicity of the dosage schedule

- the taste and palatability, and hence compliance, for young children.

It is also important to ensure that HIV-infected parents access treatment; and ART should ideally be ensured for other family members.

8.2.1. Antiretroviral drugs

Antiretroviral drugs fall into three main classes:

- nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs),

- non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), and

- protease inhibitors (see Table 24).

Table 24Classes of antiretroviral drugs recommended for use in children

| Nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors | |

|---|---|

| Zidovudine | ZDV (AZT) |

| Lamivudine | 3TC |

| Abacavir | ABC |

| Emtricitabine | FTC |

| Tenofovir | TDF |

| Non-nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors | |

| Nevirapine | NVP |

| Efavirenz | EFV |

| Protease inhibitors | |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | LPV/RTV |

| Atazanavir | ATZ |

Table 25First-line treatment regimens for children

| WHO-recommended preferred first-line antiretroviral regimens for infants and children | |

|---|---|

| First-line regimens for children < 3 years | First-line regimens for children ≥ 3 years up to 12 years |

| Abacavir (ABC)a or zidovudine (ZDV) plus Lamivudine (3TC) plus Lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/RTV)a | Abacavir (ABC)b or zidovudine (ZDV) plus Lamivudine (3TC) plus Efavirenz (EFV)b or nevirapine (NVP) |

| Abacavir (ABC) or zidovudine (ZDV) plus Lamivudine (3TC) plus Nevirapine (NVP) | Tenofovir (TDF) plus Emtricitabine (FTC) or Lamivudine (3TC) plus Efavirenz (EFV) or nevirapine (NVP) |

- a

Preferred regimen for children < 36 months regardless of exposure to nevirapine or other NNRTIs directly or via maternal treatment in preventing mother-to-child transmission.

- b

ABC+3TC+EFV is the preferred regimen for children ≥ 3 years up to 12 years.

Triple therapy is the standard of care, and first-line regimens should be based on two NRTIs plus one NNRTI or protease inhibitor.

All infants and children < 3 years of age should be started on Lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) plus two NRTIs, regardless of exposure to nevirapine (NVP) to prevent mother-to-child transmission. When viral load monitoring is available, consideration can be given to substituting LPV/r with an NNRTI after virological suppression is sustained.

For children ≥ 3 years efavirenz (EFV) is the preferred NNRTI for first-line treatment particularly once daily therapy, although NVP may be used as an alternative especially for children who are on twice daily therapy. Efavirenz is also the NNRTI of choice in children who are on rifampicin, if treatment has to start before anti-TB therapy is completed.

For drug dosages and regimens see Annex 2.

Calculation of drug dosages

In general, children metabolize protease inhibitor and NNRTI drugs faster than adults and therefore require higher equivalent doses to achieve appropriate drug levels. Drug doses must be increased as the child grows; otherwise, there is a risk for under-dosage and the development of resistance.

Drug dosages are given in Annex 2, per kilogram of body weight for some drugs and per surface area of the child for others. A table listing the equivalent weights of various surface area values is given in Annex 2 to help in calculating dosages. The use of weight bands for paediatric dosing has also simplified treatment regimens.

Formulations

Dosing in children is usually based on either body surface area or weight, or, more conveniently, on weight bands. As these change with growth, drug doses must be adjusted in order to avoid the risk for under-dosage.

8.2.2. When to start antiretroviral therapy

All HIV-infected infants and children < 60 months of age should begin ART, regardless of clinical or immunological status.

Infants and children < 60 months

- All children < 60 months of age with confirmed HIV infection should be started on ART, irrespective of clinical or immunological stage.

- Where viral testing is not available, infants < 18 months of age with clinically diagnosed presumptive severe HIV infection should start ART. Confirmation of HIV infection should be obtained as soon as possible.

Children ≥ 60 months

For children aged > 60 months, initiate ART for all those with:

- CD4 count < 500 cells/mm3 irrespective of WHO clinical stage.

- CD4 count ≤ 350 cells/mm3 which should be considered a priority, as in adults.

The decision of when to start ART should also take account of the child's social environment, including identification of a clearly defined caregiver who understands the prognosis of HIV and the requirements of ART. Occasionally immediate initiation of ART treatment may be deferred until the child is stabilized during treatment of acute infections.

In the case of confirmed or presumptive TB, initiating TB treatment is the priority. Any child with active TB should begin TB treatment immediately and start ART as soon as it can be tolerated but within the first 8 weeks of TB therapy. For children on TB treatment:

- children > 3 years and at least 10 kg, a regimen containing EFV is preferred.

- children < 3 years of age, if the child is on a LPV/r-containing regimen, consider adding RTV in a 1:1 ration of LPV:RTV to achieve a full therapeutic dose of LPV.

- A triple NNRTI-containing regimen may be used as an alternative.

8.2.3. Side-effects and monitoring

The response to and side-effects of ART should be monitored in all children on ART. A child's responses to therapy (i.e. reassessment of clinical status and stage, laboratory parameters and, symptoms of potential drug side effects or toxicity) should be done regularly. Common side effects are summarized in Table 26.

Table 26Common side-effects of antiretroviral drugs

| Drug | Abbreviation | Side-effectsa | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) | |||

| Lamivudine | 3TC | Headache, abdominal pain, pancreatitis | Well tolerated |

| Stavudineb | d4T | Headache, abdominal pain, neuropathy | Large volume of suspension capsules can be opened. |

| Zidovudine | ZDV (AZT) | Headache, anaemia, neutropenia | Do not use with d4T (antagonistic antiretroviral effect). |

| Abacavir | ABC | Hypersensitivity reaction, fever mucositis rash. If these occur, stop the drug. | Tablets can be crushed. |

| Emtricitabine | FTC | Headache, diarrhoea, nausea, and rash. May cause hepatotoxicity or lactic acidosis. | |

| Tenofovir | TDF | Renal insufficiency, decrease in bone mineral density | |

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) | |||

| Efavirenz | EFV | Strange dreams, sleepiness, rash | Take at night; avoid taking with fatty food |

| Nevirapine | NVP | Rash, liver toxicity | When given with rifampicin, increase nevirapine dose by ∼30% or avoid use. Drug interactions |

| Protease inhibitors | |||

| Lopinavir/ritonavira | LPV/RTV | Diarrhoea, nausea | Take with food; bitter taste |

| Atazanavir | ATZ | Jaundice, prolonged PR interval, nephrolithiasis | |

- a

General long-term side-effects of ART include lipodystrophy.

- b

Requires cold storage and cold chain for transport

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is a spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms associated with immune recovery brought about by a response to antiretroviral treatment. Although most HIV-infected children experience rapid benefit from ART, some undergo clinical deterioration. This is the result of either the unmasking of latent or subclinical infection or the reactivation of previously diagnosed, and often treated, conditions (infectious or non-infectious).

The onset of IRIS in children usually occurs within the first weeks to months after initiation of ART and is seen most often in children who initiate ART with very low percentge CD4+ levels (< 15%). The commonest opportunistic infections associated with IRIS in children include:

- TB the commonest;

- pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) or cryptosporidiosis;

- herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection;

- fungal, parasitic or other infections.

Where BCG immunization of infants and children is routine, BCG-associated IRIS (localized and systemic) is frequently observed.

Most cases of paradoxical IRIS resolve spontaneously, or can be managed with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, although some episodes can be severe and even lead to death.

- ►

Give specific treatment for the opportunistic infection

- ►

Start on anti-inflammatory therapy.

Occasionally, IRIS becomes progressively worse and may require a short course of treatment with corticosteroids and, rarely, temporary discontinuation of ART. The same ART regimen should be restarted once IRIS has improved.

Monitoring

In addition to checking for ART side effects, a clinical assessment should be made of the child's or caregiver's adherence to therapy and the need for additional support. The frequency of clinical monitoring depends on the response to ART. At a minimum, after the start of ART, follow-up visits should be made:

- for infants < 12 months, at weeks 2, 4 and 8 and then every 4 weeks for the first year

- for children > 12 months, at weeks 2, 4, 8 and 12 and then every 2–3 months once the child has stabilized on ART

- any time there is a problem of concern to the caregiver or intercurrent illness.

Important signs of infants' and children's responses to ART include:

- improvement in the growth in children who have been failing to grow

- improvement in neurological symptoms and development of children with encephalopathy or who had delayed achievement of developmental milestones

- decreased frequency of infections (bacterial infections, oral thrush and other opportunistic infections)

Long-term follow-up

- A clinician should see the child at least every 3 months.

- A non-clinician (ideally, the provider of ART, such as a pharmacist) should assess adherence and provide adherence counselling.

- Children who are clinically unstable should be seen more frequently, preferably by a clinician.

The organization of follow-up care depends on local expertise, and should be decentralized as much as possible.

Monitoring response at each visit:

- weight and height

- neurodevelopment

- adherence to treatment

- CD4 (%) count, if available (every 6 months)

- baseline Hb or EVF (if on ZDV/AZT) and alanine aminotransferase activity, if available

- symptom-directed laboratory testing: Hb, EVF or full blood count, alanine aminotransferase activity

8.2.4. When to change treatment

When to substitute

If toxic effects can be associated with an identifiable drug in a regimen, it can be replaced by another drug in the same class that does not have the same adverse effect. As few antiretroviral drugs are available, drug substitutions should be limited to:

- severe or life-threatening toxicity, such as:

- –

Stevens Johnson syndrome

- –

severe liver toxicity

- –

severe haematological effects

- drug interaction (e.g. TB treatment with rifampicin interfering with nevirapine or protease inhibitor).

- potential lack of adherence by the patient if he or she cannot tolerate the regimen.

When to switch

ART failure may be due to:

- poor adherence

- inadequate drug level

- prior or treatment experienced drug resistance

- inadequate potency of the drug

A reasonable trial of the therapy is required before ART is determined to be failing on clinical criteria alone:

- The child should have received the regimen for at least 24 weeks.

- Adherence to therapy should be considered optimal.

- Any opportunistic infections have been treated and resolved.

- IRIS has been excluded.

- The child is receiving adequate nutrition.

Treatment failure is identified from:

- clinical failure (clinical criteria): appearance or reappearance of WHO clinical stage 4 events after at least 24 weeks on ART, with adherence to treatment

- immunological failure (CD4 criteria): count of < 200 cells/mm3 or CD4 < 10% for a child aged < 5 years and in a child aged > 5 years persistent CD4 levels < 100 cells/mm3

- virological failure (viral load criteria): persistent viral load > 1000 RNA copies/ml after at least 24 weeks on ART, and based on two consecutive measurements within 3 months, with adherence to treatment.

When treatment failure is confirmed, switching to a second-line regimen becomes necessary.

Second-line treatment regimens

In the event of treatment failure, the entire regimen should be changed from a first-line to a second-line combination. The second-line regimen should include at least three new drugs, one or more of them in a new class. Recommending potent, effective second-line regimens for infants and children is particularly difficult because of the lack of experience in use of second-line regimens in children and the limited number of formulations appropriate for children.

After failure of a first-line NNRTI-based regimen, a regimen with boosted protease inhibitor plus two NRTIs is recommended for second-line ART. LPV/RTV is the preferred boosted protease inhibitor for a second-line ART regimen after failure of a first-line NNRTI-based regimen.

Table 27Recommended second-line treatment regimens for children

| First-line treatment | Recommended second-line treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Children< 3 years | Children ≥ 3 years up to 12 years | ||

| LPV/r-based first line | ABC + 3TC + LPV/r | No changea | ZDV + 3TC + EFV |

| ZDV + 3TC + LPV/r | No changea | ABC or TDF + 3TC + EFV | |

| NNRTI-based first line | ABC + 3TC + EFV (or NVP) | ZDV + 3TC + LPV/r | ZDV + 3TC + LPV/r |

| TDF + XTCb + EFV (or NVP) | – | ZDV + 3TC + LPV/r | |

| ZDV+ 3TC + EFV (or NVP) | ABC + 3TC + LPV/r | ABC or TDF + 3TC + LPV/r | |

- a

Could switch to NVP based regimen if the reason for failure is poor palatability of LPV/r

- b

Lamivudine (3TC) or emtricitabine (FTC)

8.3. Supportive care for HIV-positive children

8.3.1. Vaccination

HIV-exposed infants and children should receive all vaccines in the Expanded Programme for Immunization, including H. influenzae type B and pneumococcal vaccine, according to the national schedule. The schedules of the Expanded Programme might have to be modified for HIV-infected infants and children:

- Measles: Because of their increased risk for early and severe measles infection, infants with HIV should receive a dose of standard measles vaccine at 6 months of age and a second dose as soon as possible after 9 months of age, unless they are severely immunocompromised at that time.

- Pneumococcal vaccine: Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine should be given to all children, but vaccination may be delayed if the child is severely immunocompromised.

- Haemophilus influenzae: H. influenzae type B conjugate vaccine should be given to all children, but vaccination may be delayed if the child is severely immunocompromised.

- BCG: New findings indicate that infants who have HIV infection are at high risk for disseminated BCG disease. Therefore, BCG vaccine should not be given to children known to be HIV-infected. As infants cannot always be identified as HIV-infected at birth, BCG vaccine should be given to all infants at birth in areas with a high prevalence of both TB and of HIV, except those known to be infected with HIV.

- Yellow fever: Yellow fever vaccine should not be administered to children with symptomatic HIV infection.

8.3.2. Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis

Co-trimoxazole prevents PCP in infants and reduces morbidity and mortality among infants and children living with, or exposed, to HIV. Co-trimoxazole also protects against common bacterial infections, toxoplasmosis and malaria.

Who should receive co-trimoxazole?

- All infants born to HIV-infected mothers should receive co-trimoxazole 4–6 weeks after birth or at their first encounter with the health care system. They should continue until HIV infection has been excluded and they are no longer at risk of acquiring HIV from breast milk.

- All infected children should be continued on co-trimoxazole even when on ART.

How long co-trimoxazole should be given?

Adherence should be discussed at initiation and monitored at each visit. Co-trimoxazole must be taken as follows:

- HIV-exposed children: for the first year or until HIV infection has been definitively ruled out and the mother is no longer breastfeeding

- When on ART: Co-trimoxazole may be stopped once clinical or immunological indicators confirm restoration of the immune system for ≥ 6 months (also see below). It is not known whether co-trimoxazole continues to provide protection after the immune system is restored.

- Children with a history of PCP: Continue indefinitely.

Under what circumstances should co-trimoxazole be discontinued?

- If the child develops severe cutaneous reactions such as Stevens Johnson syndrome, renal or hepatic insufficiency or severe haematological toxicity

- after HIV infection has confidently been excluded in an HIV-exposed child:

- –

in a non-breastfed child aged < 18 months by a negative virological test

- –

in a breastfed child aged < 18 months by a negative virological test conducted 6 weeks after cessation of breastfeeding

- –

in a breastfed child aged > 18 months by a negative HIV serological test 6 weeks after cessation of breastfeeding

- In HIV-infected children, co-trimoxazole should be continued until they are 5 years of age and on ART with a sustained CD4 percentage > 25%.

- Co-trimoxazole should not be discontinued if not on ART.

What doses of co-trimoxazole should be used?

- ►

Recommended dosages of 6–8 mg/kg trimethoprim once daily should be used.

- –

children aged < 6 months, give one paediatric tablet (or one quarter of an adult tablet, 20 mg trimethoprim–100 mg sulfamethoxazole);

- –

children aged 6 months to 5 years, give two paediatric tablets or half an adult tablet (40 mg trimethoprim–200 mg sulfamethoxazole); and

- –

children aged > 5 years, give one adult tablet.

- ►

If the child is allergic to co-trimoxazole, dapsone is the best alternative. It can be given from 4 weeks of age at 2 mg/kg per day orally once daily.

What follow-up is required?

- Assessment of tolerance and adherence: Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis should be a routine part of the care of HIV-infected children and be assessed at all regular clinic or follow-up visits by health workers or other members of multidisciplinary care teams. Clinical follow-up could initially be monthly, then every 3 months, if co-trimoxazole is well tolerated.

8.3.3. Nutrition

The mothers of infants and young children known to be infected with HIV are strongly encouraged to breastfeed them exclusively for 6 months and to continue breastfeeding up to the age of 1 year. Older children should eat varied, energy-rich food to increase their energy intake and to ensure adequate micronutrient intake.

Children should be assessed routinely for nutritional status, including weight and height, at scheduled visits. Their energy intake might have to be increased by 25–30% if they lose weight or grow poorly.

HIV-infected children who have severe acute malnutrition should be managed according to the guidelines for uninfected children and given 50–100% additional energy-rich foods (see Chapter 7).

8.4. Management of HIV-related conditions

The treatment of most infections (such as pneumonia, diarrhoea and meningitis) in HIV-infected children is the same as in other children. In cases of treatment failure, consider giving a second-line antibiotic. Treatment of recurrent infections is the same, regardless of the number of recurrences.

Some HIV-related conditions that require specific management are described below.

8.4.1. Tuberculosis

In a child with suspected or proven HIV infection, a diagnosis of TB should always be considered, although it is often difficult to confirm. Early in HIV infection, when immunity is not impaired, the signs of TB are similar to those in a child without HIV infection. Pulmonary TB is still the commonest form of TB, even in HIV-infected children. As HIV infection progresses and immunity declines, dissemination of TB becomes more common, and tuberculous meningitis, miliary TB and widespread tuberculous lymphadenopathy occur.

HIV-infected infants and children with active TB should begin TB treatment immediately. If they are not yet started on ART, this should be started as soon as it is tolerated, within the first 8 weeks of TB therapy, irrespective of CD4 count and clinical stage (see section 8.2.2).

- ►

Treat TB in HIV-infected children with the same anti-TB drug regimen as for uninfected children with TB. (Refer to national TB guidelines, or see section 4.7.2.)

Isoniazid preventive therapy

All HIV-infected infants and children should be screened for TB infection, as they are at special risk. If a child has cough, fever or weight loss, assess for TB. If the child does not have TB, give isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) daily for 6 months.

- ►

Give isoniazid preventive therapy to:

- all HIV-infected infants and children exposed to TB from household contacts, but with no evidence of active disease, are well and thriving.

- children > 12 months living with HIV infection, including those previously treated for TB, who are not likely to have active TB and are not known to be exposed to TB

- ►

Give 10 mg/kg isoniazid daily for at least 6 months. See the child monthly and give a 1-month supply of isoniazid at each visit.

Note: Infants living with HIV infection who are unlikely to have active TB and are not known to have been exposed to TB should not receive isoniazid preventive therapy as part of HIV care.

8.4.2. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

PCP should be suspected in any HIV-positive infant with severe pneumonia. If PCP is untreated, mortality from this condition is very high. It is therefore imperative to provide treatment as early as possible.

Diagnosis

- is most likely in a child < 12 months (peak age, 4–6 months),

- subacute or acute onset of non-productive cough and difficulty in breathing,

- no or low-grade fever,

- cyanosis or persistent hypoxia,

- poor response to 48 h of first-line antibiotics for pneumonia, and

- elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase.

Although clinical and radiological signs are not diagnostic, the presence of severe respiratory distress (tachypnoea, chest indrawing and cyanosis), with disproportionate clear chest or diffuse signs on auscultation and low oxygen saturation are typical of PCP infection.

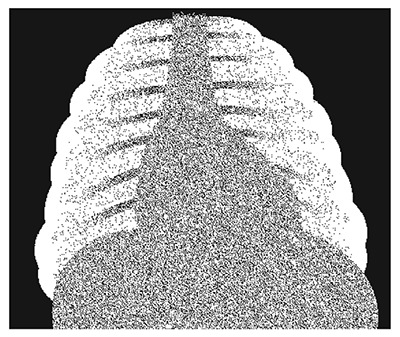

- A chest X-ray is falsely negative in 10–20% of proven cases of PCP but typically shows a bilateral diffuse interstitial reticulogranular (‘ground glass’) pattern, with no hilar lymph nodes or effusion. PCP may also present with pneumothorax.

Induced sputum and nasopharyngeal aspiration are useful for obtaining sputum for examination.

Treatment

- ►

Promptly give oral or preferably IV high-dose co-trimoxazole (8 mg/kg trimethoprim–40 mg/kg sulfamethoxazole) three times a day for 3 weeks.

- ►

If the child has a severe drug reaction, change to pentamidine (4 mg/kg once a day) by IV infusion for 3 weeks. For management of a child presenting with clinical pneumonia in settings with a high HIV prevalence, see section 4.2.

- ►

Prednisolone at 1–2 mg/kg per day for 1 week may be helpful early in the disease if severe hypoxia or severe respiratory distress is present.

- ►

Continue co-trimoxazole prophylaxis on recovery, and ensure that ART is given.

8.4.3. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis

Diagnosis

The child is often asymptomatic in the early stages but may later have:

- persistent cough, with or without difficulty in breathing,

- bilateral parotid swelling,

- persistent generalized lymphadenopathy,

- hepatomegaly and other signs of heart failure, and

- finger-clubbing.

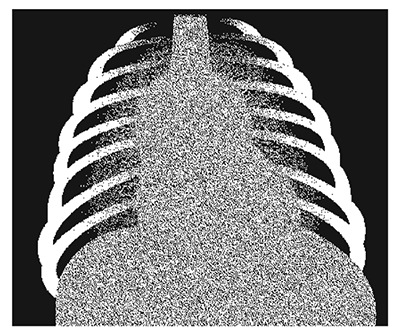

- Chest X-ray: Suspect lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis if the chest X-ray shows a bilateral reticulonodular interstitial pattern, which should be distinguished from pulmonary TB and bilateral hilar adenopathy (see figure).

Treatment

- ►

Give a trial of antibiotic treatment for bacterial pneumonia (see section 4.2) before starting treatment with prednisolone.

- ►

Start treatment with steroids only if the chest X-ray shows lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis, plus any of the following signs:

- –

fast or difficult breathing

- –

cyanosis

- –

pulse oximetry reading of oxygen saturation ≤ 90%.

- ►

Give oral prednisolone at 1–2 mg/kg per day for 2 weeks. Then decrease the dose over 2–4 weeks, depending on the response to treatment. Beware of reactivating TB.

- ►

Start ART if not already on treatment.

8.4.4. Fungal infections

Oral and oesophageal candidiasis

- ►

Treat oral thrush with nystatin (100 000 U/ml) suspension. Give 1–2 ml into the mouth four times a day for 7 days. If this is not available, apply 1% gentian violet solution. If these are ineffective, give 2% miconazole gel at 5 ml twice a day, if available.

Suspect oesophageal candidiasis if the child has difficulty or pain while vomiting or swallowing, is reluctant to take food, is salivating excessively or cries during feeding. The condition may occur with or without evidence of oral thrush. If oral thrush is not found, give a trial of treatment with fluconazole. Exclude other causes of painful swallowing (such as cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, lymphoma and, rarely, Kaposi sarcoma), if necessary by referral to a larger hospital where appropriate testing is possible.

- ►

Give oral fluconazole (3–6 mg/kg once a day) for 7 days, except if the child has active liver disease.

- ►

Give amphotericin B (0.5 mg/kg once a day) by IV infusion for 10–14 days to children who don't respond to oral therapy or are unable to tolerate oral medications or risk disseminated candidiasis (e.g. a child with leukopenia).

Cryptococcal meningitis

Suspect cryptococcus as a cause in any HIV-infected child with signs of meningitis. The presentation is often subacute, with chronic headache or only mental status changes. An India ink stain of CSF confirms the diagnosis.

- ►

Treat with amphotericin at 0.5–1.5 mg/kg per day for 14 days, then with fluconazole 6–12 mg/kg (maximum 800 mg) for 8 weeks.

- ►

Start fluconazole 6 mg/kg daily (maximum 200 mg) prophylaxis after treatment.

8.4.5. Kaposi sarcoma

Consider Kaposi sarcoma in children presenting with nodular skin lesions, diffuse lymphadenopathy and lesions on the palate and conjunctiva with periorbital bruising. Diagnosis is usually clinical but can be confirmed by a needle biopsy of skin lesions or lymph node. Suspect Kaposi sarcoma also in children with persistent diarrhoea, weight loss, intestinal obstruction, abdominal pain or large pleural effusion. Consider referral to a larger hospital for management.

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia: typical hilar lymphadenopathy and lace-like infiltrates

Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP): typical ‘ground glass’ appearance

8.5. Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission, and infant feeding

8.5.1. Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission

HIV may be transmitted during pregnancy, labour and delivery or through breastfeeding. The best way to prevent transmission is to prevent HIV infection in general, especially in pregnant women, and to prevent unintended pregnancies in HIV-positive women. If an HIV-infected woman becomes pregnant, she should be provided with ART, safe obstetric care and counselling and support for infant feeding.

HIV-infected pregnant women should be given ART both to benefit their own health and to prevent HIV transmission to their infants during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

- ►

Start lifelong ART for all pregnant women with HIV infection regardless of symptoms.

In order to eliminate paediatric HIV there are two main options, which should start early in pregnancy, at 14 weeks or as soon as possible thereafter. These options significantly reduce mother-to-child transmission:

- ►

Option B: A three-drug prophylactic regimen for the mother taken during pregnancy and throughout breastfeeding, as well as infant prophylaxis for 6 weeks after birth, whether or not the infant is breastfeeding.

- ►

Option B+: A Triple ARV treatment regimen for the mother beginning in pregnancy and continued for life, as well as infant prophylaxis for 6 weeks after birth, whether or not the infant is breastfeeding.

Option B+ is now preferred.

8.5.2. Infant feeding in the context of HIV infection

In the absence of any interventions, 15–25% of HIV-positive mothers will infect their infants during pregnancy or delivery; if they breastfeed, there is an additional absolute risk of 5–20%. Although avoidance of breastfeeding eliminates the risk for HIV transmission through breast milk, replacement feeds have been associated with increased infant morbidity and mortality.

Exclusive breastfeeding during the first months of life carries less risk for HIV transmission than mixed feeding, and it provides considerable protection against infectious diseases and other benefits.

ART greatly reduces the risk for HIV transmission, while simultaneously ensuring that the mother receives appropriate care to improve her own health. If an HIV-positive mother breastfeeds her infant while taking ART and gives ART to her infant each day, the risk for transmission is reduced to 2% or 4% if she breastfeeds for 6 or 12 months, respectively. It is important to:

- Support mothers known to be HIV-positive in achieving the greatest likelihood that their child will be HIV-free and survive, while taking into consideration their own health.

- Balance the prevention of HIV transmission against meeting the nutritional requirements and protection of infants against non-HIV morbidity and mortality.

- HIV-positive mothers should preferably receive lifelong ART treatment to improve their own health, and the infant should be put on ART prophylaxis while breastfeeding.

Infant feeding advice

National guidelines should be followed in the feeding of an HIV-exposed infant: to either breastfeed while receiving ART (mother or infant) or to avoid breastfeeding.

- ►

When national guidelines recommend that HIV-positive mothers should breastfeed and take ART to prevent transmission, mothers should breastfeed their infants exclusively for the first 6 months of life, introducing appropriate complementary foods thereafter, and should continue breastfeeding for the first 12 months of life.

- ►

When a decision has been taken to continue breastfeeding because the child is already infected, ART treatment and infant feeding options should be discussed for future pregnancies.

- ►

If the mother is known to be HIV-positive and the child's HIV status is unknown, the mother should be counselled about the benefits of breastfeeding as well as the risk for transmission, and the child should be tested. If replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable and safe, avoidance of further breastfeeding is recommended. Otherwise, exclusive breastfeeding should be practised until 6 months of age, breastfeeding continued up to 12 months and complimentary feeding provided.

Mothers will require continued counselling and support to feed their infants optimally. Counselling should be done by a trained, experienced counsellor. Local people experienced in counselling should be consulted, so that the advice given is consistent. If the mother is using breast-milk substitutes, counsel her about their correct use and demonstrate safe preparation.

8.6. Follow-up

8.6.1. Discharge from hospital

HIV-infected children may respond slowly or incompletely to the usual treatment. They may have persistent fever, persistent diarrhoea and chronic cough. If the general condition of these children is good, they need not remain in hospital but can be seen regularly as outpatients.

8.6.2. Referral

If the necessary facilities are not available, consider referring a child suspected of having HIV infection:

- for HIV testing with pre- and post-test counselling

- to another centre or hospital for further investigations or second-line treatment if there has been little or no response to treatment

- to a trained counsellor for HIV and infant feeding, if the local health worker cannot do this

- to a community or home-based care programme, a community or institution-based voluntary counselling and testing centre or a community-based social support programme for further counselling and continuing psychosocial support.

Orphans must be referred to essential services, including health care education and birth registration.

8.6.3. Clinical follow-up

Children who are known to be HIV-infected should, when not ill, attend well-infant clinics like other children. In addition, they need regular clinical follow-up at first-level facilities to monitor their:

- –

clinical condition

- –

growth

- –

nutritional intake

- –

vaccination status

They should also be given psychosocial support, if possible in community programmes.

8.7. Palliative and end-of-life care

An HIV-infected, immunologically compromised child often has considerable discomfort, so good palliative care is essential. All decisions should be taken with the parents or caretaker, and the decisions should be clearly communicated to other staff (including night staff). Consider palliative care at home as an alternative to hospital care. Some treatments for pain control and relief of distressing conditions (such as oesophageal candidiasis or convulsions) can significantly improve the quality of the child's remaining life.

Give end-of-life (terminal) care if:

- –

the child has progressively worsening illness

- –

everything possible has been done to treat the presenting illness.

Ensuring that the family has appropriate support to cope with the impending death of the child is an important part of care in the terminal stages of HIV/AIDS. Parents should be supported in their efforts to give palliative care at home so that the child is not kept in hospital unnecessarily.

8.7.1. Pain control

The management of pain in HIV-infected children follows the same principles as for other chronic diseases, such as cancer and sickle-cell disease. Particular attention should be paid to ensuring that the care is culturally appropriate and sensitive.

- Give analgesics in two steps according to whether the pain is mild or moderate-to-severe.

- Give analgesics regularly (‘by the clock’), so that the child does not have to experience recurrence of severe pain in order to obtain another dose of analgesic.

- Administer by the most appropriate, simplest, most effective and least painful route, by mouth when possible (IM treatment can be painful).

- Tailor the dose for each child, because children have different dose requirements for the same effect, and progressively titrate the dose to ensure adequate pain relief.

Use the following drugs for effective pain control:

Mild pain: such as headaches

- ►

Give paracetamol or ibuprofen to children > 3 months who can take oral medication. For children < 3 months of age, use only paracetamol.

- –

paracetamol at 10–15 mg/kg every 4–6 h

- –

ibuprofen at 5–10 mg/kg every 6–8 h

Moderate-to-severe pain and pain that does not respond to the above treatment: strong opioids

- ►

Give morphine orally or IV every 4–6 h or by continuous IV infusion

- ►

If morphine does not adequately relieve the pain, then switch to alternative opioids, such as fentanyl or hydromorphone.

Note: Monitor carefully for respiratory depression. If tolerance develops, the dose should be increased to maintain the same degree of pain relief.

Adjuvant medicines: There is no sufficient evidence that adjuvant therapy relieves persistent pain or specific types such as neuropathic pain, bone pain and pain associated with muscle spasm in children. Commonly used drugs include diazepam for muscle spasm, carbamazepine for neuralgic pain and corticosteroids (such as dexamethasone) for pain due to an inflammatory swelling pressing on a nerve.

Pain control for procedures and painful lesions in the skin or mucosa

Local anaesthetics: during painful procedures, lidocaine should be infiltrated at 1–2%; for painful lesions in the skin or mucosa:

- ►

lidocaine: apply (with gloves) on a gauze pad to painful mouth ulcers before feeds; acts within 2–5 min

- ►

tetracaine, adrenaline and cocaine: apply to a gauze pad and place over open wounds; particularly useful during suturing

8.7.2. Management of anorexia, nausea and vomiting

Loss of appetite during a terminal illness is difficult to treat. Encourage carers to continue providing meals and to try:

- giving small feeds more frequently, particularly in the morning when the child's appetite may be better

- giving cool foods rather than hot foods

- avoiding salty or spicy foods

- giving oral metoclopramide (1–2 mg/kg) every 2–4 h, if the child has distressing nausea and vomiting.

8.7.3. Prevention and treatment of pressure sores

Teach carers to turn the child at least once every 2 h. If pressure sores develop, keep them clean and dry. Use local anaesthetics such as tetracaine, adrenaline and cocaine to relieve pain.

8.7.4. Care of the mouth

Teach carers to wash out the mouth after every meal. If mouth ulcers develop, clean the mouth at least four times a day with clean water or salt solution and a clean cloth rolled into a wick. Apply 0.25% or 0.5% gentian violet to any sores. If the child has a high fever or is irritable or in pain, give paracetamol. Crushed ice wrapped in gauze and given to the child to suck may give some relief. If the child is bottle-fed, advise the carer to use a spoon and cup instead. If a bottle continues to be used, advise the carer to clean the teat with water before each feed.

If oral thrush develops, apply miconazole gel to the affected areas at least three times a day for 5 days, or give 1 ml nystatin suspension four times a day for 7 days, pouring it slowly into the corner of the mouth so that it reaches the affected parts.

If there is pus due to a secondary bacterial infection, apply tetracycline or chloramphenicol ointment. If there is a foul smell in the mouth, give IM benzylpenicillin (50 000 U/kg every 6 h), plus oral metronidazole suspension (7.5 mg/kg every 8 h) for 7 days.

8.7.5. Airway management

Give priority to keeping the child comfortable rather than prolonging life.

8.7.6. Psychosocial support

Helping parents and siblings through their emotional reaction towards the dying child is one of the most important aspects of care in the terminal stage of HIV disease. How this is done depends on whether care is being given at home, in hospital or in a hospice. At home, much of the support can be given by close family members, relatives and friends.

Keep up to date on how to contact local community home care programmes and HIV/AIDS counselling groups. Find out if the carers are receiving support from these groups. If not, discuss the family's attitude towards these groups and the possibility of linking the family with them.

- Children with HIV/AIDS - Pocket Book of Hospital Care for ChildrenChildren with HIV/AIDS - Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...