Evidence review for principles of care

Evidence review H

NICE Guideline, No. 116

Authors

National Guideline Alliance (UK).Principles of care

This evidence report contains information on 1 review relating to the treatment of PTSD.

- Review question 6.1 For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?

Review question For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?

Introduction

Adults, children and young people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often report that the level of support available from healthcare and social care professionals can be variable. As a result of the perceived variation in the level of support and information given to adults, children and young people with PTSD and their parents and/or carers, the committee considered it was important to investigate what care and support was required. This review aims to provide guidance that will support health and social care services to standardise access to, and appropriately delivery, treatment across the country.

Summary of the protocol (PICO table)

Please see Table 1 for a summary of the Condition, Perspective, Study Design, Outcome, and Evaluation of this review.

Table 1

Summary of the protocol (PICO table).

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Methods and processes

This evidence review was developed using the methods and process described in Developing NICE guidelines: the manual; see the methods chapter for further information.

Declarations of interest were recorded according to NICE’s 2014 and 2018 conflicts of interest policies.

Clinical evidence

Included studies

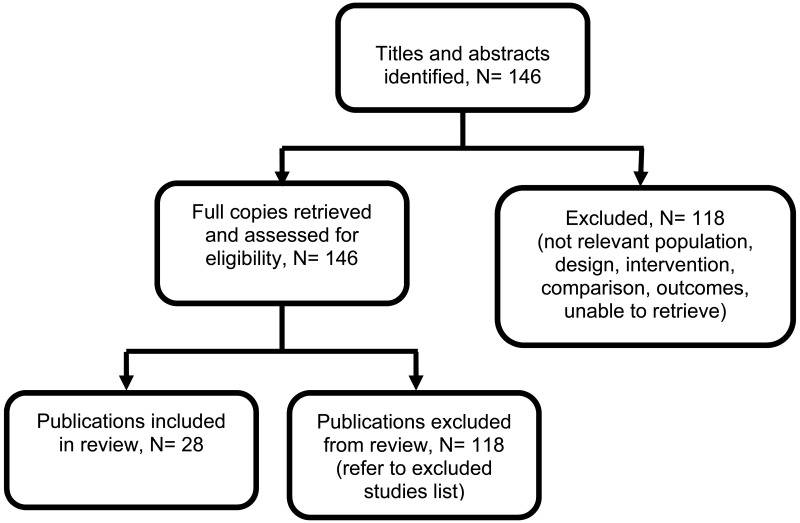

One hundred and forty-six studies were identified for full-text review. Of these 146 studies, 28 primary qualitative studies (N= 716) were included in the review (Bance 2014; Bermudez 2013; Borman 2013; Dittman & Jensen 2014; Eisenman 2008; Ellis 2016; Ellison 2012; Ghafoori 2014; Hundt 2015; Jindani & Khalsa 2015; Kaltman 2014; Kaltman 2016; Kehle-Forbes 2017; Murray 2016; Niles 2016; Palmer 2004; Possemato 2015; Possemato 2017; Salloum 2015; Salloum 2016; Stankovic 2011; Story & Beck 2017; Taylor 2013; Tharp 2016; Valentine 2016; Vincent 2013; West 2017; Whealin 2016).

The clinical studies included in this evidence review are summarised in Table 2 and evidence from these are summarised in the clinical GRADE-CERQual evidence profile below (Table 3).

See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix C – Clinical evidence study selection and study evidence tables in Appendix D – Clinical evidence tables.

Excluded studies

One hundred and eighteen studies were reviewed at full text and excluded from this review. Common reasons for exclusion included population outside scope, study design, non-systematic review and non-OECD country.

Studies not included in this review with reasons for their exclusions are provided in

Appendix K – Excluded studies.

Summary of qualitative studies included in the evidence review

Table 2 provides a brief summary of the included studies. See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix C.

Table 2

Summary of included studies.

Quality assessment of clinical studies included in the evidence review

The clinical evidence profile for this review question the principles of care and support for people with PTSD and their families and carers are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Summary clinical evidence profile (CERQual approach for qualitative findings).

Economic evidence

A systematic review of the economic literature was conducted but no relevant studies were identified which were applicable to this review question. Economic modelling was not undertaken for this question because other topics were agreed as higher priorities for economic evaluation.

Resource impact

The recommendations made by the committee based on this review are not expected to have a substantial impact on resources. The committee’s considerations that contributed to the resource impact assessment are included under the ‘Cost effectiveness and resource use’ in ‘The committee’s discussion of the evidence’ section.

Evidence statements

Four themes emerged from the evidence provided from the interviews, focus groups and free-text written responses with children, young people and adults with PTSD. The themes centred on the apprehension of engaging in interventions or services, the utilisation of peer support groups, involvement of family members and carers, and the requirement of flexibility in the delivery of treatment. The four broad themes that emerged after review of the literature were: ‘Apprehension engaging in the intervention or service’, ‘organisation of the intervention or service’, ‘sharing common experience’ and ‘intervention provision by a trusted expert’.

Apprehension engaging in the intervention or service

Nineteen studies with a quality assessment range of 10-18, and an overall high confidence rating, reported on the theme apprehension engaging in the interventions or service.

In these studies, participants felt apprehension engaging in the intervention or service, and reported difficulties engaging with a therapist, stigmatisation and fear of re-traumatisation, although some participants expressed a therapeutic component to reflection of their traumatic experience.

Organisation of the intervention or service

Eighteen studies with a quality assessment range of 10-18, and an overall high confidence rating, reported on the theme organisation of the intervention or service.

In these studies, participant expressed limited awareness of interventions and services, the need for clear and structured interventions and services, flexibility in the setting of interventions, involvement of family members and carers in treatment, the requirement for post intervention or service follow-up and configuration of interventions and services.

Sharing common experiences

Eighteen studies with a quality assessment range of 10-18, and an overall high confidence rating, reported on the theme sharing common experiences.

In these studies, participants described peer recommendations as a source of engagement in services and interventions and participants expressed the perceived benefits of sharing their experiences with others who have also experienced a traumatic event. However, some participants described a reluctance to engage in peer support and they suggested support should be tailored to the individual.

Intervention provision by a trusted expert

Eighteen studies with a quality assessment range of 10-18, and an overall high confidence rating, reported on the theme intervention provision by a trusted expert.

In these studies, participants described avoidance of relational support from family members or friends favouring support from trusted experts. Participants expressed trust in professionals to provide appropriate and effective interventions and services.

The committee’s discussion of the evidence

Interpreting the evidence

The outcomes that matter the most

All outcomes in this review (themes that emerged from qualitative meta-synthesis) were in line with the phenomenon of interest listed in the protocol (factors or attributes that can enhance or inhibit access to services; factors or attributes that can enhance or inhibit uptake of and engagement with intervention and services; actions by services that could improve or diminish the experience of care; experience of specific service developments or models of service delivery) and were considered critical outcomes. The outcomes considered were deliberately very broad in order not to inhibit themes and sub-themes that emerged inductively through the qualitative synthesis.

The quality of the evidence

An adapted GRADE approach CERQual was used to assess the evidence by themes. Similar to GRADE in effectiveness reviews, this includes 4 domains of assessment and an overall rating:

- Limitations across studies for a particular finding or theme.

- Coherence of findings (equivalent to heterogeneity but related to unexplained differences or incoherence of descriptions).

- Applicability of evidence (equivalent to directness, i.e. how much the finding applies to our review protocol).

- Saturation or sufficiency (this related particularly to interview data and refers to whether all possible themes have been extracted or explored).

The committee agreed that the review included a range of well-conducted primary studies and was both comprehensive and of high quality. In addition, the themes that emerged were in line with the experience reported by the lay members of the committee and the concerns about experience of care expressed by clinical members of the committee. A limitation noted by the committee was the small number of studies which directly explored the experience of children with PTSD (K=3), however, the committee agreed that the principles that emerged from the more substantive adult review were equally applicable to children.

Benefits and harms

The committee recognised that a significant proportion of the qualitative findings were covered by existing recommendations (sections 1.3, 1.4 and 1.6 in the short guideline), however, these recommendations were reworded to more accurately reflect the needs of service users. One of these areas concerned the involvement of families and carers, where the committee agreed to recommend that family and carers were involved in treatment for people for PTSD where appropriate, rather than routinely, in order to reflect the somewhat mixed experiences from the qualitative evidence review that suggest that family involvement may not always be desirable and/or helpful.

Another area where the committee considered it appropriate to amend an existing recommendation (section 1.3 of the short guideline) based on the high quality of the included studies was in terms of flexible modes of intervention delivery. The committee discussed the preference for flexibility that emerged from the qualitative review and considered this in the context of the quantitative evidence for the clinical efficacy of some of these remote approaches, for example, computerised trauma-focused CBT, that suggests that patient preference can be promoted without a negative impact on therapeutic benefit. A theme emerging from the qualitative synthesis was a preference for home-based interventions. However, the committee had safety concerns around recommending home-based interventions, and considered it more appropriate to recommend care in non-clinical settings, giving examples of settings this could include (schools or offices).

The committee also considered it appropriate to amend existing recommendations (section 1.3 and 1.6 of the short guideline) about promoting access to services based on the high quality of the included studies, in order to emphasise that service users are very apprehensive about engaging in interventions or services. The committee discussed the finding that service users often find it difficult to engage with their therapist, and agreed the importance of facilitating patient preference in order to ameliorate this barrier. For example, if a female therapist is preferred by a woman who has been abused by a man. The committee also discussed challenges in terms of uptake and engagement of interventions. This finding emerged from the qualitative review, in terms of a service user need for information about services available and follow-up support, and this theme resonated with the clinical experience of the committee. In light of this, the committee agreed to amend an existing recommendation in order to highlight the need for proactive patient-centred strategies to enable people with PTSD to access appropriate treatment and facilitate the uptake of and engagement with therapeutic interventions.

An area where there was no evidence for clinical efficacy but where the qualitative meta-synthesis suggested potential benefits was for peer support groups as it is recognised it can be difficult for people with PTSD to engage socially. The committee considered that the potential benefits of peer support groups included facilitating access to services (through signposting, support and encouragement offered by peers) and could help individuals at risk of social isolation to integrate with others with shared experiences. The committee discussed how peer support groups should be offered in a way that reduces the risk of exacerbating symptoms and considered it important that the groups be constituted in a way that minimises this risk, for example, by considering the composition of the group in terms of trauma type (for instance, it might not be appropriate to include a woman who has experienced childhood sexual abuse in a predominantly male combat-related trauma peer support group). The committee also agreed that the potential risk of exacerbating symptoms could be minimised through facilitation by people with mental health training and supervision, and the provision of information and support.

The committee acknowledged the difficulties that some service-users faced at the end of an intervention or service, namely that the abrupt transition out of treatment was challenging. Therefore, the committee pointed out that there was a need for a continuation of care at the end of trauma-focused treatment, where appropriate.

Cost effectiveness and resource use

No economic evidence is available for this review question. The evidence review indicated that people with PTSD might be apprehensive or anxious and avoid engaging in treatment. Therefore, the committee advised engagement strategies be implemented, such as following up service users who miss appointments, providing multiple points of access to the service and offering flexible modes of delivery, such as remote care using text messages, email, telephone or video consultation, or care in non-clinical settings such as schools or offices. These recommendations are good practice points that will help improve consistency of care. The committee acknowledged that all these engagement strategies have a modest resource impact. However they expressed the view that ensuring that people with PTSD feel and are able to access services is likely to lead to more timely management, fewer missed appointments and lower rates of early discontinuation of treatment, which, in turn, are likely to result in better clinical outcomes and to prevent further downstream costs incurred by a delay in service provision or by sub-optimal clinical outcomes due to low engagement with treatment. The recommendation to facilitate access to peer support groups has some resource implications, as peer support groups are not routinely offered across settings, however they are in fairly widespread use. The recommendation is expected to promote earlier access to support and lead to improved treatment adherence, as some treatment modalities have significant discontinuation rates, which, subsequently, can lead to improved clinical and cost effectiveness of treatment.

References for included studies

Bance 2014

Bance S, Links PS, Strike C, et al. (2014) Help-seeking in transit workers exposed to acute psychological trauma: A qualitative analysis. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation 48(1), 3–10. [PubMed: 23803431]Bermudez 2013

Bermudez D, Benjamin MT, Porter SE, et al. (2013) A qualitative analysis of beginning mindfulness experiences for women with post-traumatic stress disorder and a history of intimate partner violence. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 19(2), 104–108 [PubMed: 23561069]Borman 2013

Bormann JE, Hurst S and Kelly A (2013) Responses to mantram repetition program from veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development 50(6), 769–784 [PubMed: 24203540]Dittman & Jensen 2014

Dittmann I and Jensen TK (2014) Giving a voice to traumatized youth—Experiences with trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Child abuse & neglect 38(7), 1221–30 [PubMed: 24367942]Eisenman 2008

Eisenman DP, Meredith LS, Rhodes H, et al. (2008) PTSD in Latino Patients: Illness Beliefs, Treatment Preferences, and Implications for Care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23(9), 1386–1392 [PMC free article: PMC2518000] [PubMed: 18587619]Ellis 2016

Ellis LA (2016) Qualitative changes in recurrent PTSD nightmares after focusing-oriented dreamwork. Dreaming 26(3), 185–201Ellison 2012

Ellison ML, Mueller L, Smelson D, et al. (2012) Supporting the education goals of post-9/11 veterans with self-reported PTSD symptoms: a needs assessment. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal 35(3), 209–217 [PubMed: 22246119]Ghafoori 2014

Ghafoori B, Barragan B and Palinkas L (2014) Mental Health Service Use After Trauma Exposure: A Mixed Methods Study. The Journal of nervous and mental disease 202(3), 239–246 [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000108] [PMC free article: PMC3959109] [PubMed: 24566510] [CrossRef]Hundt 2015

Hundt NE, Mott JM, Miles SR, et al. (2015) Veterans’ perspectives on initiating evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 7(6), 539–546 [PubMed: 25915648]Jindani & Khalsa 2015

Jindani FA and Khalsa GFS (2015) A yoga intervention program for patients suffering from symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative descriptive study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 21(7), 401–408 [PubMed: 26133204]Kaltman 2014

Kaltman S, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Gonzales F and Serrano A (2014) Preferences for Trauma-Related Mental Health Services Among Latina Immigrants From Central America, South America, and Mexico (Vol. 6)Kaltman 2016

Kaltman S, Hurtado de Mendoza A, Serrano A and Gonzales FA (2016) A Mental Health Intervention Strategy for Low-Income, Trauma-Exposed Latina Immigrants in Primary Care: A Preliminary Study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 86(3), 345–354 [PMC free article: PMC4772137] [PubMed: 26913774]Kehle-Forbes 2017

Kehle-Forbes SM, Harwood EM, Spoont MR, et al. (2017) Experiences with VHA care: a qualitative study of U.S. women veterans with self-reported trauma histories. BMC Womens Health 17(1), 38 [DOI:10.1186/s12905-017-0395-x] [PMC free article: PMC5450063] [PubMed: 28558740] [CrossRef]Murray 2016

Murray H, Merritt C, Grey N (2016) Clients’ experiences of returning to the trauma site during PTSD treatment: an exploratory study. Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy 44(4), 420–30 [PubMed: 26190531]Niles 2016

Niles BL, Mori DL, Polizzi CP, et al. (2016) Feasibility, qualitative findings and satisfaction of a brief Tai Chi mind-body programme for veterans with post-traumatic stress symptoms. BMJ Open 6(11), (no pagination)(e012464) [PMC free article: PMC5168527] [PubMed: 27899398]Palmer 2004

Palmer S, Stalker C, Gadbois S and Harper K (2004) What Works for Survivors of Childhood Abuse: Learning from Participants in an Inpatient Treatment Program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 74(2), 112–121 [PubMed: 15113240]Possemato 2015

Possemato K, Acosta MC, Fuentes J, et al. (2015) A Web-Based Self-Management Program for Recent Combat Veterans With PTSD and Substance Misuse: Program Development and Veteran Feedback. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 22(3), 345–358 [PMC free article: PMC4480783] [PubMed: 26120269]Possemato 2017

Possemato K, Kuhn E, Johnson EM, et al. (2017) Development and refinement of a clinician intervention to facilitate primary care patient use of the PTSD Coach app. Translational Behavioral Medicine 7(1), 116–126 [PMC free article: PMC5352634] [PubMed: 27234150]Salloum 2015

Salloum A, Dorsey CS, Swaidan VR, Storch EA (2015) Parents’ and children’s perception of parent-led Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Child Abuse & Neglect 40, 12–23 [PubMed: 25534316]Salloum 2016

Salloum A, Swaidan VR, Torres AC, et al. (2016) Parents’ perception of stepped care and standard care trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies 25(1), 262–274 [PMC free article: PMC4788389] [PubMed: 26977133]Stankovic 2011

Stankovic L (2011) Transforming trauma: a qualitative feasibility study of integrative restoration (iRest) yoga Nidra on combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. International journal of yoga therapy (21), 23–37 [PubMed: 22398342]Story & Beck 2017

Story KM and Beck BD (2017) Guided Imagery and Music with female military veterans: An intervention development study. Arts in Psychotherapy 55, 93–102Taylor 2013

Taylor B, Carswell K and Williams AC (2013) The interaction of persistent pain and post-traumatic re-experiencing: A qualitative study in torture survivors. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 46(4), 546–555 [PubMed: 23507129]Tharp 2016

Tharp AT, Sherman M, Holland K, et al (2016) A qualitative study of male veterans’ violence perpetration and treatment preferences. Military medicine 181(8), 735–739 [PMC free article: PMC6242277] [PubMed: 27483507]Valentine 2016

Valentine SE, Dixon L, Borba CP, et al. (2016) Mental illness stigma and engagement in an implementation trial for Cognitive Processing Therapy at a diverse community health center: A qualitative investigation. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health 9(2), 139–150 [PMC free article: PMC4972095] [PubMed: 27499808]Vincent 2013

Vincent F, Jenkins H, Larkin M and Clohessy S (2013) Asylum-seekers’ experiences of trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: a qualitative study. Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy 41(5), 579–593 [PubMed: 22794141]West 2017

West J, Liang B and Spinazzola J (2017) Trauma sensitive yoga as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative descriptive analysis. International Journal of Stress Management 24(2), 173–195 [PMC free article: PMC5404814] [PubMed: 28458503]Whealin 2016

Whealin JM, Jenchura EC, Wong AC and Zulman DM (2016) How Veterans With Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Comorbid Health Conditions Utilize eHealth to Manage Their Health Care Needs: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Journal of medical Internet research 18(10), e280. [Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb .cgi?T=JS&CSC =Y&NEWS =N&PAGE =fulltext&D =medl&AN=27784650] [PMC free article: PMC5103157] [PubMed: 27784650]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocols

Review protocol for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

Table

women who have been exposed to sexual abuse or assault, or domestic violence lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual or transgender people

Appendix B. Literature search strategies

Literature search strategy for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

Clinical evidence

Database: Medline

Last searched on Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R), Embase, PsycINFO

Date of last search: 31 January 2017

Database: CDSR, DARE, HTA, CENTRAL

Date of last search: 31 January 2017

Database: CINAHL PLUS

Health economic evidence

Note: evidence resulting from the health economic search update was screened to reflect the final dates of the searches that were undertaken for the clinical reviews (see review protocols

Database: Medline

Last searched on Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R), Embase, PsycINFO

Date of last search: 1 March 2018

Database: HTA, NHS EED

Appendix C. Clinical evidence study selection

Clinical evidence study selection for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Clinical evidence table for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

Download PDF (281K)

References for included studies

- Bance, S., Links, P. S., Strike, C., Bender, A., Eynan, R., Bergmans, Y., … Antony, J. (2014). Help-seeking in transit workers exposed to acute psychological trauma: A qualitative analysis. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation, 48(1), 3–10. [PubMed: 23803431]

- Bermudez, D., Benjamin, M. T., Porter, S. E., Saunders, P. A., Myers, N. A. L., & Dutton, M. A. (2013). A qualitative analysis of beginning mindfulness experiences for women with post-traumatic stress disorder and a history of intimate partner violence. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 19(2), 104–108. [PubMed: 23561069]

- Bormann, J. E., Hurst, S., & Kelly, A. (2013). Responses to mantram repetition program from veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 50(6), 769–784. [PubMed: 24203540]

- Dittmann, I. and T. K. Jensen (2014). Giving a voice to traumatized youth experiences with trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy. Child Abuse & Neglect 38(7): 1221–1230. [PubMed: 24367942]

- Eisenman, D. P., Meredith, L. S., Rhodes, H., Green, B. L., Kaltman, S., Cassells, A., & Tobin, J. N. (2008). PTSD in latino patients: Illness beliefs, treatment preferences, and implications for care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(9), 1386–1392. [PMC free article: PMC2518000] [PubMed: 18587619]

- Ellis, L. A. (2016). Qualitative changes in recurrent PTSD nightmares after focusing-oriented dreamwork. Dreaming, 26(3), 185–201.

- Ellison, M. L., Mueller, L., Smelson, D., Corrigan, P. W., Torres Stone, R. A., Bokhour, B. G., … Drebing, C. (2012). Supporting the education goals of post-9/11 veterans with self-reported PTSD symptoms: a needs assessment. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal, 35(3), 209–217. [PubMed: 22246119]

- Ghafoori, B., Barragan, B., & Palinkas, L. (2014). Mental Health Service Use After Trauma Exposure: A Mixed Methods Study. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 202(3), 239–246. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000108 [PMC free article: PMC3959109] [PubMed: 24566510] [CrossRef]

- Hundt, N. E., Mott, J. M., Miles, S. R., Arney, J., Cully, J. A., & Stanley, M. A. (2015). Veterans’ perspectives on initiating evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(6), 539–546. [PubMed: 25915648]

- Jindani, F. A., & Khalsa, G. F. S. (2015). A yoga intervention program for patients suffering from symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative descriptive study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(7), 401–408. [PubMed: 26133204]

- Kaltman, S., de Mendoza, A. H., Serrano, A., & Gonzales, F. A. (2016). A Mental Health Intervention Strategy for Low-Income, Trauma-Exposed Latina Immigrants in Primary Care: A Preliminary Study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(3), 345–354. [PMC free article: PMC4772137] [PubMed: 26913774]

- Kaltman, S., Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A., Gonzales, F., & Serrano, A. (2014). Preferences for Trauma-Related Mental Health Services Among Latina Immigrants From Central America, South America, and Mexico (Vol. 6).

- Kehle-Forbes, S. M., Harwood, E. M., Spoont, M. R., Sayer, N. A., Gerould, H., & Murdoch, M. (2017). Experiences with VHA care: A qualitative study of U.S. women veterans with self-reported trauma histories. BMC Women’s Health, 17 (1) (no pagination)(38). [PMC free article: PMC5450063] [PubMed: 28558740]

- Murray, H., Merritt, C., & Grey, N. (2016). Clients’ Experiences of Returning to the Trauma Site during PTSD Treatment: An Exploratory Study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 44(4), 420–430. doi:10.1017/S1352465815000338 [PubMed: 26190531] [CrossRef]

- Niles, B. L., Mori, D. L., Polizzi, C. P., Kaiser, A. P., Ledoux, A. M., & Wang, C. (2016). Feasibility, qualitative findings and satisfaction of a brief Tai Chi mind-body programme for veterans with post-traumatic stress symptoms. BMJ Open, 6 (11) (no pagination)(e012464). [PMC free article: PMC5168527] [PubMed: 27899398]

- Palmer, S., Stalker, C., Gadbois, S., & Harper, K. (2004). What Works for Survivors of Childhood Abuse: Learning from Participants in an Inpatient Treatment Program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(2), 112–121. [PubMed: 15113240]

- Possemato, K., Acosta, M. C., Fuentes, J., Lantinga, L. J., Marsch, L. A., Maisto, S. A., … Rosenblum, A. (2015). A Web-Based Self-Management Program for Recent Combat Veterans With PTSD and Substance Misuse: Program Development and Veteran Feedback. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(3), 345–358. [PMC free article: PMC4480783] [PubMed: 26120269]

- Possemato, K., Kuhn, E., Johnson, E. M., Hoffman, J. E., & Brooks, E. (2017). Development and refinement of a clinician intervention to facilitate primary care patient use of the PTSD Coach app. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 7(1), 116–126. [PMC free article: PMC5352634] [PubMed: 27234150]

- Salloum, A., Dorsey, C.S., Swaidan, V.R., & Storch, E.A. (2015). Parents and children’s perception of parent-led Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Child Abuse & Neglect 40, 12–23. [PubMed: 25534316]

- Salloum, A., Swaidan, V. R., Torres, A. C., Murphy, T. K., & Storch, E. A. (2016). Parents’ perception of stepped care and standard care trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(1), 262–274. [PMC free article: PMC4788389] [PubMed: 26977133]

- Stankovic, L. (2011). Transforming trauma: a qualitative feasibility study of integrative restoration (iRest) yoga Nidra on combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. International journal of yoga therapy(21), 23–37. [PubMed: 22398342]

- Story, K. M., & Beck, B. D. (2017). Guided Imagery and Music with female military veterans: An intervention development study. Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 93–102.

- Taylor, B., (2013). The interaction of persistent pain and post-traumatic re-experiencing: A qualitative study in torture survivors. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 46(4): 546–555. doi.10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.10.281 [PubMed: 23507129] [CrossRef]

- Tharp, A. T., Sherman, M., Holland, K., Townsend, B., & Bowling, U. (2016). A qualitative study of male veterans’ violence perpetration and treatment preferences. Military medicine, 181(8), 735–739. [PMC free article: PMC6242277] [PubMed: 27483507]

- Valentine, S. E., Dixon, L., Borba, C. P., Shtasel, D. L., & Marques, L. (2016). Mental illness stigma and engagement in an implementation trial for Cognitive Processing Therapy at a diverse community health center: A qualitative investigation. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 9(2), 139–150. [PMC free article: PMC4972095] [PubMed: 27499808]

- Vincent, F., Jenkins, H., Larkin, M., & Clohessy, S. (2013). Asylum-seekers’ experiences of trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: a qualitative study. Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy, 41(5), 579–593. [PubMed: 22794141]

- West, J., Liang, B., & Spinazzola, J. (2017). Trauma sensitive yoga as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative descriptive analysis. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(2), 173–195. [PMC free article: PMC5404814] [PubMed: 28458503]

- Whealin, J. M., Jenchura, E. C., Wong, A. C., & Zulman, D. M. (2016). How Veterans With Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Comorbid Health Conditions Utilize eHealth to Manage Their Health Care Needs: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Journal of medical Internet research, 18(10), e280. [PMC free article: PMC5103157] [PubMed: 27784650]

Appendix E. Forest plots

Forest plots for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

As the information that has been uncovered is all qualitative, forest plots are not applicable to this review.

Appendix F. GRADE CERQual tables

GRADE CERQual tables for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

As the information that has been uncovered is all qualitative, all relevant information can be found in the summary clinical evidence profiles.

Appendix G. Economic evidence study selection

Economic evidence study selection for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

A global health economics search was undertaken for all areas covered in the guideline. The flow diagram of economic article selection across all reviews is provided in Appendix A of Supplement 1 – Methods Chapter’.

Appendix H. Economic evidence tables

Economic evidence tables for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

No health economic evidence was identified for this review.

Appendix I. Health economic evidence profiles

Health economic evidence profiles for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

No health economic evidence was identified for this review and no economic modelling was undertaken.

Appendix J. Health economic analysis

Health economic analysis for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

No health economic analysis was conducted for this review.

Appendix K. Excluded studies

Excluded studies for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

Clinical studies

Economic studies

No economic studies were reviewed at full text and excluded from this review.

Appendix L. Research recommendations

Research recommendations for “For adults, children and young people with clinically important post-traumatic stress symptoms, what factors should be taken into account in order to provide access to care, optimal care and coordination of care?”

No research recommendations were made for this review question.

Final

Evidence reviews

Evidence reviews

These evidence reviews were developed by the National Guideline Alliance hosted by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian.

Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties.

NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government, Scottish Government, and Northern Ireland Executive. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn.