NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (US). Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD). Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 58.)

Introduction

This TIP adopts the IOM continuum of care model, which sees prevention as a step along a continuum that also incorporates treatment and maintenance (see Figure 1.1, below). The IOM model defines three types of prevention: universal, selective, and indicated.

Figure 1.1

The IOM Continuum of Care Model. Source: Springer & Phillips, 2006; 2007.

- Universal prevention “[a]ddresses [the] general public or [a] segment of [the] entire population with average probability, risk or condition of developing [a] disorder” (Springer & Phillips, 2007). Universal prevention can take a variety of forms, including media campaigns, large-scale health initiatives (e.g., immunization), point-of purchase signage, and warning labels on products.

- Selective prevention is designed for a “[s]pecific sub-population with risk significantly above average, either imminently or over [his or her] lifetime” (Springer & Phillips, 2007), and can include “screening women for alcohol use, training healthcare professionals, working with family members of pregnant women who abuse alcohol, developing biomarkers, brief interventions, and referrals” (Grant, 2011).

- Indicated prevention “[a]ddresses identified individuals with minimal but detectable signs or symptoms suggesting a disorder” (Springer & Phillips, 2007), such as pregnant women who drink heavily, or women who have already given birth to a child with FASD and continue to drink. Indicated prevention can include some of the same methods applied in selective prevention, but applied more intensively based on the severity of the alcohol-related problem.

One act of AEP prevention can positively impact the life of the mother and the life of the unborn child. One change in how services are provided can multiply that impact many times over.

For the purposes of the AEP prevention discussion in this chapter, women of childbearing age (i.e., females age 10–49) in your treatment setting should receive AEP prevention based on the following:

- Universal prevention: A woman who is not pregnant, and either reports no alcohol use or does not screen positive for at-risk alcohol use;

- Selective prevention: A woman of childbearing age who reports alcohol use but has only one of the two indicators for an indicated intervention; she is either pregnant but does not screen positive for at-risk alcohol use, or she screens positive for at-risk alcohol use but is not pregnant; or

- Indicated prevention: A woman of childbearing age who screens positive for at-risk alcohol use and is pregnant.

This chapter will first discuss screening, then appropriate brief interventions for AEP prevention in each of the three categories, before discussing treatment issues and referral. In each category, screening is a vital starting point before moving on to appropriate prevention, treatment, or referral.

Professional Responsibility to Screen

As the box “Risk Factors for an AEP” (next page) makes clear, a variety of factors can impact a woman's consumption of alcohol during pregnancy. These and other factors make it critical to inquire about alcohol use among all women of childbearing age in behavioral health settings for alcohol consumption:

- There is no known safe level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy, and even low levels of prenatal alcohol exposure have been shown to negatively impact a fetus (Chang, 2001).

- Screening facilitates the implementation of appropriate interventions, at the earliest possible point (Leonardson, Loudenburg, & Struck, 2007).

- Prevented AEP can result in significant cost savings through prevented cases of FASD and reduced use of the health and social services systems (Abel & Sokol, 1991; Astley et al., 2000a; Lupton et al., 2004; Astley, 2004a).

- Screening is an ethical obligation, one that should be conducted equally of men and women regardless of race and economic status, and which should be performed with women using instruments that are designed for women (Committee on Ethics of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2008). Additionally, in an FASD prevention study assessing the feasibility of identifying high-risk women through the FASD diagnostic evaluation of their children, Astley and colleagues (2000a) concluded that these women are not only at high risk for producing more children damaged by alcohol exposure, but they themselves often face serious adverse social, mental, and physical health issues, as well. Thus, one could argue that it would be unethical to ignore their existence and ignore opportunities to provide them with advocacy support and primary prevention intervention.

- Awareness does create change: Statistics from SAMHSA's NSDUH (May 21, 2009) suggest that drinking rates among women drop considerably during pregnancy, particularly in the second and third trimesters when there is a much higher awareness of pregnancy status.

Risk Factors for an AEP

Substance Abuse/Mental Health Factors

- History of alcohol consumption (NIAAA, 2000; Bobo, Klepinger, & Dong, 2007)

- Family background of alcohol use (Stratton et al., 1996; Leonardson et al., 2007)

- History of inpatient treatment for drugs or alcohol and/or history of inpatient mental health treatment (Project CHOICES Research Group, 2002)

Personal/Sexual/Family Factors

- Previous birth to a child with an FASD (Kvigne et al., 2003; Leonardson et al., 2007)

- Lack of contraception use/unplanned pregnancy (Astley et al., 2000b)

- Physical/emotional/sexual abuse (Astley et al., 2000b)

- Partner substance use/abuse (Stratton et al., 1996; Leonardson et al., 2007)

- Multiple sex partners (Project CHOICES Research Group, 2002)

- Smoking (CDC, 2002; Leonardson et al., 2007)

- Never having been tested for HIV (Anderson, Ebrahim, Floyd, & Atrash, 2006)

- Lack of education, income, and/or access to care (Astley et al., 2000a)

In addition, screening:

- Gives the client permission to talk about drinking;

- Helps to identify and or clarify co-occurring issues;

- Minimizes surprises in the treatment process; and

- Can mean more effective treatment.

Drinking Rates Among Pregnant Women

According to SAMHSA's 2010 NSDUH, “Among pregnant women aged 15 to 44, an estimated 10.8 percent reported current alcohol use, 3.7 percent reported binge drinking, and 1.0 percent reported heavy drinking. These rates were significantly lower than the rates for non-pregnant women in the same age group (54.7, 24.6, and 5.4 percent, respectively). Binge drinking during the first trimester of pregnancy was reported by 10.1 percent of pregnant women aged 15 to 44” (Office of Applied Studies [OAS], 2011). All of these estimates are based on data averaged over 2009 and 2010. (Binge drinking for women has been defined by NIAAA as four or more drinks on one occasion [2004]).

In telephone interviews with 4,088 randomly selected control mothers from the CDC's National Birth Defects Prevention Study who delivered live born infants without birth defects during 1997–2002, Ethen and colleagues (2009) found even higher numbers: 30.3 percent of respondents reported alcohol use during pregnancy, with 8.3 percent reporting binge drinking during pregnancy (approximately 97 percent of those indicating binge drinking stating that it was during the first trimester).

In addition, one study of stool and hair samples of neonates who had been prenatally exposed to heavy ethanol use suggested that these children were also 3.3 times more likely to have been exposed to amphetamines and twice as likely to have been exposed to opiates, both of which can also impair long-term child development (Shor, Nulman, Kulaga, & Koren, 2010). Another recent study found that, among 1,400 patients with prenatal alcohol exposure attending an FASD diagnostic clinic in Washington state, 62 percent were prenatally exposed to tobacco, 37 percent were prenatally exposed to marijuana, and 38 percent were prenatally exposed to crack cocaine (Astley, 2010).

Statistics from SAMHSA's TEDS and from SAMHSA's NSDUH indicate a potentially greater need to address the FASD issue specifically in substance abuse treatment settings: More than 22 percent of pregnant women admitted into treatment from 1992 to 2006 indicated alcohol as their primary substance of abuse (OAS, 2006).

Lastly, 49 percent of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended (Finer & Henshaw, 2006). As a result, many women will consume alcohol without knowing that they are pregnant.

Procedures for Screening

Behavioral health settings are busy, and screening procedures must be efficient. Figure 1.2, Screening Decision Tree for AEP Prevention, provides a procedure for an opening question about alcohol use, moving on to screening (if necessary), suggested instruments for screening, and next steps. The goal of screening is to determine, as quickly and as accurately as possible, whether a client is at risk and therefore brief intervention and treatment or referral is warranted.

Figure 1.2

A Screening Decision Tree for AEP Prevention. AEP prevention can be simple and brief. The TIP consensus panel developed the following Screening Decision Tree for AEP Prevention to help behavioral health providers quickly touch upon the topic of alcohol (more...)

The screening instruments recommended in Figure 1.2 are not the only options available for determining client alcohol use, but are validated as indicated in the decision tree (Sokol & Clarren, 1989; Russell, 1994; Chang, 2001). Nonetheless, if your agency does not use these instruments or does not have a ‘perfect’ alternative, it is better to screen with what is available to your program than to not screen women of childbearing age at all.

Part 3 of this TIP, the online Literature Review, includes further discussion of these and other alcohol screening instruments for use with women.

Screening should be done with sensitivity to the client's level of health literacy, or, “the degree to which people have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (Parker, Ratzan, & Lurie, 2003; Liechty, 2011). More than a third of adults in the United States do not have adequate health literacy (Kutner, 2006; Liechty, 2011), so the prevention message may need to be simplified and reinforced by asking the client on several occasions and in a variety of ways. This means that your agency will likely need to screen at several different points in time.

In addition, talking about alcohol use or seeking help for an alcohol-related problem can be potentially embarrassing or difficult for the client (NIAAA, 2005). Counselors should be conscious of this risk, and be respectful when raising the issue of alcohol use. Additional sources of information that can help to identify alcohol use include collateral reports from family and friends of the client, and client medical/court records.

Vignette #2 in Part 1, Chapter 3 incorporates discussion of drink size and the use of a visual aid with a client.

Selecting an Appropriate Prevention Approach

Based on the results of your client screening, the next step is to decide on an appropriate brief approach: Universal prevention message or selective or indicated brief intervention. Brief interventions are associated with sustained reduction in alcohol consumption by women of childbearing age, and those discussed have shown promise for being adaptable to various settings and needs (Fleming, Barry, Manwell, Johnson, & London, 1997; Manwell, Fleming, Mundt, Stauffacher, & Barry, 2000; Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003; Project CHOICES Intervention Research Group, 2003; Chang et al., 2005; Grant, Ernst, Streissguth, & Stark, 2005; O'Connor & Whaley, 2007).

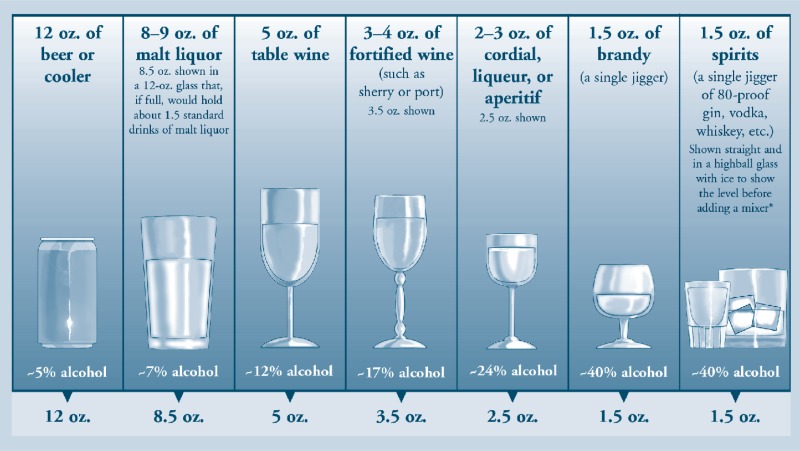

What Is a Standard Drink?

All clients being screened for alcohol consumption should be given a clear indication of what constitutes a ‘standard drink.’ A standard drink in the United States is any drink that contains about 14 grams of pure alcohol (about 0.6 fluid ounces or 1.2 tablespoons). Below are U.S. standard drink equivalents. These are approximate, since different brands and types of beverages vary in their actual alcohol content.

When using these prevention approaches, counselors should remember that no intervention constitutes full treatment of a woman's alcohol use. Each is designed simply to encourage a dialogue about alcohol and begin a process of change. Each should be the basis for ongoing evaluation and an informed approach to treatment or referral. For programs that do not have existing approaches to substance abuse treatment, procedures for appropriate referral are discussed after the brief interventions.

Universal Prevention

As indicated in Figure 1.2, Screening Decision Tree for AEP Prevention, a woman who is not pregnant, and either reports no alcohol use or does not screen positive for at-risk alcohol use, can receive a simple universal prevention message. Consider the following scripted messages.

Universal AEP Prevention Statement and Possible Follow-Up Questions

“It's great that you're choosing not to drink alcohol. I know you aren't currently pregnant or planning to become pregnant, but you are in the primary childbearing years right now. If you change your mind about pregnancy or discover in the future that you are pregnant, or you do begin to drink, please keep in mind that research has shown a link between drinking during pregnancy and the baby having an FASD. A child with an FASD can have physical and behavior problems, as well as cognitive problems (or, problems with the brain). These effects are caused by the alcohol, and they don't go away, although they can be treated. There is no known safe amount of alcohol to consume during pregnancy, and any type of alcohol can cause FASD.

Can I give you a brochure [or Web address, such as www.fasdcenter.samhsa.gov]to take with you? This will explain more about FASD and how to have a healthy baby. Even if you aren't planning to become pregnant, you could share it with a friend or family member who is.”

| If asked: | Why is there no known safe amount of alcohol that a woman can have during pregnancy? |

|---|---|

| Answer: | The amount of alcohol required to damage an unborn baby differs based on the individual. Things like how much alcohol a woman drinks, how often she drinks during pregnancy, and which trimesters she drinks in all play a part. It also depends on genetics, whether the woman smokes or uses other drugs, her general health and nutrition, her age, and her levels of stress or trauma. That's why the Surgeon General recommends that pregnant women not drink any alcohol at all. |

| If asked: | What kinds of alcohol should I avoid? |

| Answer: | All alcohol can harm a baby while you're pregnant, not just beer, wine, and hard liquor. Wine coolers and ‘alco-pops’ also count. Anything with alcohol. Even some over-the-counter medications have a lot of alcohol in them; if you're pregnant or thinking of becoming pregnant, you should be careful about those, too. |

| If asked: | Where can I find more information about FASD? |

| Answer: | In addition to the SAMHSA FASD Center for Excellence (www |

Whether asked for more information or not, the universal AEP prevention message should be accompanied by appropriate awareness materials, either in print or via a Web address. The SAMHSA FASD Center for Excellence provides a series of consumer fact sheets called What You Need to Know that provides helpful information about how to have a healthy baby. Appendix C, Public and Professional Resources on FASD, has links to additional information resources.

At the same time, counselors should keep in mind with universal AEP prevention that, in some situations, women may deny using alcohol, but a combination of signs and symptoms suggest otherwise. In such cases, it may be prudent to re-screen frequently (Taylor, Bailey, Peters, & Stein, 2009).

Selective Prevention

The following section discusses two brief interventions for AEP prevention that are appropriate with women of childbearing age who report alcohol use but have only one of the two indicators for an indicated intervention; they are either pregnant but do not screen positive for at-risk alcohol use, or they screen positive for at-risk alcohol use but are not pregnant. These are organized in terms of the time required to perform the intervention effectively. As with universal prevention, each of these approaches should be accompanied by appropriate FASD information material, such as the What You Need to Know fact sheets, either in hard copy or through a Web link.

The first selective intervention, called ‘FLO’ for short, is a simple, three-step approach (see box below). An example of using the FLO approach with a client is illustrated in Vignette #1 in Part 1, Chapter 3 of this TIP.

FLO (Feedback, Listen, Options)

| 1. | Provide Feedback about screening results. If possible, confirm the results with additional screening and provide information about recommended drinking limits. (For women who are—or are planning to become—pregnant, the ideal goal is abstinence.) |

| 2. | Ask clients for their views about their own drinking and Listen carefully to encourage their thinking and decision-making process. |

| 3. | Provide medical advice, and negotiate a decision about Options clients can pursue, including establishing a goal and developing an action plan. |

Source: Higgins-Biddle J, Hungerford D, Cates-Wessel K. Screening and brief interventions (SBI) for unhealthy alcohol use: A step-by-step implementation guide for trauma centers. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2009. [Parenthetical in #1 added.]

The second selective intervention, FRAMES, is a more established and slightly more detailed method for motivating a client toward change, and has demonstrated positive results in brief intervention situations (Miller & Sanchez, 1994; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). See the box on the following page.

Each of these brief interventions discusses ‘action plans’ or strategies for changing alcohol-related behaviors. For counselors who are not already well-versed in substance use-related change strategies, NIAAA has provided a brief guide to simple change strategies in the publication Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much (2007). Basic strategies to discuss with the client can include:

- What specific steps the client will take (e.g., not go to a bar after work, measure all drinks at home, alternate alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages);

- How drinking will be tracked (diary, kitchen calendar);

- How the patient will manage high-risk situations; and

- Who might be willing to help the client avoid alcohol use, such as a significant other or a non-drinking friend.

FRAMES

| F | Feedback Compare the patient's level of drinking with drinking patterns that are not risky. She may not be aware that what she considers normal is actually risky (or that any consumption during pregnancy creates risk). |

|---|---|

| R | Responsibility Stress that it is her responsibility to make a change. |

| A | Advice Give direct advice (not insistence) to change her drinking behavior. |

| M | Menu Identify risky drinking situations and offer options for coping. |

| E | Empathy Use a style of interaction that is understanding, non-judgmental, and involved. |

| S | Self-efficacy Elicit and reinforce self-motivating statements such as, “I am confident that I can stop drinking.” Encourage the patient to develop strategies, implement them, and commit to change. |

Source: Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2002. [Italics in “Feedback” added.]

Indicated Prevention: Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention (SBI)

Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention (SBI) is a workbook-based brief intervention that is appropriate with women of childbearing age who screen positive for at-risk alcohol use and are pregnant. SBI generally takes 10 to 15 minutes to complete, and has been shown to positively impact abstinence rates and key subsequent health factors in the newborn, including higher birth weight/length and lower mortality (O'Connor & Whaley 2007).

The WIC Project Care: Health and Behavior Workbook was originally developed for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) programs, which provide support to current and expecting mothers, but the workbook can be used across settings. It is crafted in very simple language and uses traditional brief intervention techniques, including education and feedback, ognitive–behavioral procedures, goal-setting, and contracting. The care provider should go through the workbook with the client. As with both universal and selective prevention, the SBI approach should be accompanied by appropriate FASD print materials or a relevant and reliable Web link for further information.

The workbook can be downloaded for free in multiple languages from the WIC Web site: http://www.phfewic.org/Projects/Care.aspx

Providing Intervention/Treatment: Additional Factors to Consider

The following are factors to keep in mind when delivering a brief intervention for AEP prevention, as well as when delivering full substance abuse treatment (for agencies that are able to offer such care).

- Selective and indicated prevention services should be delivered by someone with motivational interviewing (MI) skills if at all possible. While a detailed discussion of MI techniques is outside the scope of this TIP, SAMHSA provides a Web site (http://www.motivationalinterview.org/) that contains extensive materials and training resources for providers looking to develop their MI skills. See also TIP 35, Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Abuse Treatment (SAMHSA, 1999).

- Consider the woman's age and circumstances, and how these impact intervention/treatment. For example, life factors and obstacles to abstinence (family responsibilities, work, other children, etc.) will probably be very different for a teen vs. an older woman.

- Consider cultural context, as well; the cultural factors that impact treatment may be very different for an African-American, Hispanic/Latina, Asian-American, or Native-American woman (or a woman of any other minority) than for a Caucasian woman.

- Be willing to make modifications (e.g., frequency, duration) to maximize opportunities for prevention and recovery.

- Include and engage families in treatment, including significant others, grandparents, guardians, and custodians.

- Include relapse prevention.

- Include family support skills.

- Consider additional counseling factors:

- –

Parenting skills (that work for both the parent and the child)

- –

Trauma and abuse

- –

Co-occurring mental health issues

- Using a calendar with a client who is already pregnant may help her differentiate when she found out she was pregnant from when she actually became pregnant. She may have consumed alcohol for some time before knowing of the pregnancy, and showing that the drinking occurred even before she knew she was pregnant can help her feel less pressured and alleviate feelings of guilt. Clients may feel guilty and not tell the whole truth (or even withhold the truth). This means that getting an accurate picture of alcohol use may require multiple screenings. It is critical to build trust over several sessions. [Vignette #4 in Part 1, Chapter 3 demonstrates the use of a calendar with a client.]

- Watch for clients who ‘shut down’ on the topic of alcohol, and be understanding if the client experiences a sense of panic about what she may have unintentionally done to her baby.

- If the client is not pregnant but is drinking, and is not resistant to talking about contraception, qualified professionals can consider adding a discussion of effective contraception (see box, “Ensuring Effective Contraception”) to discussions about drinking reduction.

Ensuring Effective Contraception

A woman who drinks alcohol at risky levels may not always follow prescribed procedures for effective contraception (Astley et al., 2000b). Review contraception use with her to ensure that she has full contraceptive coverage every time she has sexual intercourse. This might include providing secondary, back-up, or emergency contraception methods. For example, along with oral contraceptives, advise her to use condoms, which have the added benefit of reducing sexually transmitted diseases.

Source: Division of Women's Health Issues. Drinking and reproductive health: A Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders prevention tool kit. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2006. .

Approaches to Resistance

With any approach to AEP prevention, counselors should keep in mind that, while a female client may feel safe enough to share about her alcohol use, she may not be ready to take the next step of comprehensive assessment and treatment (Astley et al., 2000b). A woman may present as resistant, reluctant, resigned, or rationalizing. The publication Substance Abuse During Pregnancy: Guidelines for Screening (Taylor et al., 2009) provides guidance on meeting these various forms of resistance. In addition, see the box below.

Procedures for Referral

If you believe, based on screening and interaction during intervention, that your client requires assistance that is best delivered in another care setting (or treatment in another setting becomes necessary due to factors such as criminal justice or social service involvement), you should discuss the benefits of treatment with the client and offer to provide her with a referral to a local substance abuse treatment center or other appropriate provider. A general list of treatment facilities can be searched through The SAMHSA Treatment Locator (http://findtreatment.samhsa.gov). Additional referral possibilities include the following:

- County substance abuse services;

- 12-Step programs;

- Hospital treatment programs;

- Mental health programs; and

- Special pregnancy-related programs, which can be identified through your state health department by calling 800-311-BABY (2229), or 800-504-7081 for Spanish.

Resistant, Reluctant, Resigned, or Rationalizing

|

|---|

| Provider Response: Work with the resistance. Avoid confrontation and try to solicit the woman's view of her situation. Ask her what concerns her about her use and ask permission to share what you know, and then ask her opinion of the information. Accept that the process of change is a gradual one and it may require several conversations before she feels safe about discussing her real fears. This often leads to a reduced level of resistance and allows for a more open dialogue. Try to accept her autonomy but make it clear that you would like to help her quit or reduce her use if she is willing. |

|

| Provider Response: Empathize with the real or possible results of changing (for example, her partner may leave). It is possible to give strong medical advice to change and still be empathetic to possible negative outcomes to changing. Guide her problem-solving. |

|

| Provider Response: Instill hope, explore barriers to change. |

|

| Provider Response: Decrease discussion. Listen, rather than responding to the rationalization. Respond to her by empathizing and reframing her comments to address the conflict between wanting a healthy baby and not knowing whether “using” is really causing harm. |

Sources: Taylor P, Bailey D, Peters R, Stein B. Substance abuse during pregnancy: Guidelines for screening. Olympia, WA: Washington State Department of Health; 2009. .

DiClemente CC. Motivational interviewing and stages of change. In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behaviors. New York: Guilford; 1991. pp. 191–206..

Targeted Referral Options

| Non-Pregnant Women: Project CHOICES | |

|---|---|

| Project CHOICES is an evidence-based intervention (Project CHOICES Intervention Research Group, 2003; Floyd et al., 2007) that targets women at risk of having an AEP before they become pregnant. The goal is to reduce drinking and/or prevent pregnancy through contraception. The target population for Project CHOICES is women ages 18 to 44 who are sexually active and drinking alcohol at risk levels. The model uses a four-session intervention approach based in MI methods, and discussions in each session are tailored to the client's self-rated readiness to change and interest in discussing alcohol use or contraception. Project CHOICES programs exist in multiple settings, including residential and outpatient substance abuse treatment, community mental health treatment, jails, and community-based teen programs for girls. Eligibility criteria include 1) self-report of being sexually active, 2) being non-pregnant (but able to conceive), 3) high-risk drinking (8 or more drinks per week or 4 or more drinks in one occasion) in the past 30 days, 4) ineffective use of or no contraception, and 5) not currently trying to become pregnant or planning to try in the next 6 months. | Intervention Components:

|

| The CDC provides additional information about Project CHOICES at http://www | |

| Pregnant Women: Parent-Child Assistance Program (PCAP) | |

| The Parent-Child Assistance Program (PCAP) is a scientifically validated (Grant et al., 2005) paraprofessional case management model that provides support and linkages to needed services to women for 3 years following enrollment. The goal is to reduce future AEP by increasing abstinence from alcohol and drug use and/or improving regular use of reliable contraception among enrollees. The target population for PCAP is pregnant or post-partum women (up to 6 months) who have had an AEP and will self-report drug and/or alcohol use during the target pregnancy. The model is based in Relational Theory, the Stages of Change, and harm reduction. PCAP programs exist in a variety of settings, including substance abuse treatment and family support centers. Eligibility criteria include self-report of heavy alcohol or illicit drug use during pregnancy and ineffective or non-engagement with community social services. | Intervention Components:

|

| To learn more about PCAP, including contact information, background materials, an implementation guide, and relevant forms and materials, visit http://depts | |

Programs throughout the United States have worked and are working directly with the SAMHSA FASD Center for Excellence to implement SBI (summarized above), Project CHOICES, or the Parent-Child Assistance Program (PCAP) (both summarized in the box ”Targeted Referral Options,). A program near you can be considered a source for possible referral or for guidance on locating a similar program. Please contact the FASD Center for Excellence for current program contact information (www.fasdcenter.samhsa.gov). Your local FASD State Coordinator may also be able to provide guidance on appropriate referrals. The National Association of FASD State Coordinators can be contacted via the SAMHSA FASD Center for Excellence Web site: http://fasdcenter.samhsa.gov/statesystemsofcare/nafsc.aspx.

The feasibility of fully implementing SBI, Project CHOICES, or PCAP in your agency will depend on your staff skill set, your collaborative network, your funding, and a variety of other factors that are examined in greater detail in the Administrative section (Part 2) of this TIP.

Providing a Referral: Additional Factors to Consider

- Discuss possible strategies for the client to stop consuming alcohol; for example, individual counseling, 12-Step programs, and other treatment programs. Studies have shown that people given choices are more successful in treatment (Taylor et al., 2009).

- Use an advocate or special outreach services, if available, such as PCAP or Maternity Support Services (Taylor et al., 2009). Refer to Appendix C, Public and Professional Resources on FASD, for additional sources of information on community supports.

- Obtain information about costs, which health plans cover alcohol services (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare, state assistance, and public programs), who to contact to refer a patient, the phone numbers, and the necessary procedures for enrollment. This will allow you to tailor the referral to the client's needs and health insurance coverage (Higgins-Biddle, Hungerford, & Cates-Wessel, 2009).

- Identify the types of services available in your area (e.g., cognitive-behavioral, 12-Step, Motivational Enhancement Therapy) and the types of modalities (e.g., in-patient, outpatient), and prepare short descriptions of the available options so patients can understand the differences among alternative approaches (Higgins-Biddle et al., 2009).

- If possible, help the client make an appointment while she is in your office. If the woman is unwilling to make that commitment, ask if she would like some information to take with her if she should change her mind. Schedule the next visit, continue to maintain interest in her progress, and support her efforts to change. Monitor and follow up on any co-existing psychiatric conditions (Taylor et al., 2009).

- Maintain communication with the substance abuse treatment or other provider to monitor progress (Taylor et al., 2009).

- If immediate substance abuse treatment or other support is not available, the counselor or designated staff might meet with the woman weekly or bi-weekly to express concern and to acknowledge the seriousness of the situation (Taylor et al., 2009).

Helping Your Clients Receive Culturally Competent Services

| This TIP, like all others in the TIP series, recognizes the importance of delivering culturally competent care. Cultural competency, as defined by HHS, is… “A set of values, behaviors, attitudes, and practices within a system, organization, program, or among individuals that enables people to work effectively across cultures. It refers to the ability to honor and respect the beliefs, language, interpersonal styles, and behaviors of individuals and families receiving services, as well as staff who are providing such services. Cultural competence is a dynamic, ongoing, developmental process that requires a long-term commitment and is achieved over time” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003, p. 12). This section discusses national information resources that are available on the topic of cultural competence or for providing care to specific cultural groups (listed alphabetically). However, the absence of a specific cultural group from this section is not meant to suggest that cultural competency is not an issue for that population. Individuals from all cultural backgrounds deserve respect and attention in a treatment environment, and the significance of culture needs to be recognized in relation to many different areas of a person's life; race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, socioeconomic status, language, etc. Chapter 3 of this TP, Clinical Vignettes, contains additional information on the essential elements of culturally competent counseling. |

| Hispanic/Latin Populations If your agency is not fully capable in serving Hispanic/Latin clients or a Hispanic/Latin client requests culturally specific services, the National Council of La Raza provides a search tool (http://www In addition, SAMHSA's National Hispanic & Latino Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) offers a variety of products and resources focused on the health needs of Hispanics and Latinos. Visit their Web site at http://www |

| Native Populations If your agency is not fully capable in serving native clients or a native client requests culturally specific services, the Indian Health Service (IHS) provides an interactive search map (http://www If you are unable to locate services through the map, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) provides the HRSA Health Center locator (http: |

| Cultural Competency Training/Learning The SAMHSA FASD Center for Excellence can provide training or technical assistance (TA) on cultural competency topics, or can put your agency in touch with a nearby specialist. Training and TA request forms can be accessed online (http://www In addition, the HRSA's Culture, Language and Health Literacy page (http://www |

Working with Women Who May Have an FASD

When working with women of childbearing age, counselors may encounter clients who exhibit symptoms or characteristics suggesting that they themselves have an FASD. Research has identified intergenerational FASD as a pattern (Kvigne et al., 2003; May et al., 2005). Verifying the presence of an FASD is a process of observation, interviewing, and additional screening that takes time. The guidelines provided in the next chapter, Addressing FASD in Treatment, can prove helpful for counselors who want to pursue verification of a possible FASD in the client, and/or wish to modify their approach to delivering prevention or treatment/referral accordingly.

For more information on AEP prevention…

Vignettes 1–4 in Part 1, Chapter 3 illustrate scenarios where a counselor practices AEP prevention approaches. In addition, Part 3, the online literature review, also contains further discussion of screening and prevention interventions.

- Prevention of Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies Among Women of Childbearing Age - Addr...Prevention of Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies Among Women of Childbearing Age - Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

- Clinical Vignettes - Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)Clinical Vignettes - Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

- Background and Clinical Strategies for FASD Prevention and Intervention - Addres...Background and Clinical Strategies for FASD Prevention and Intervention - Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

- Administrator's Guide to Implementing FASD Prevention and Intervention - Address...Administrator's Guide to Implementing FASD Prevention and Intervention - Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

- Preface - Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)Preface - Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...