NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (US). Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD). Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 58.)

Introduction

This chapter presents vignettes of counseling/intervention sessions between various service professionals and either 1) women of childbearing age where FASD prevention is warranted, and/or 2) individuals who have or may have an FASD or their family members. The vignettes are intended to provide real-world examples and overviews of approaches best suited (and not suited to) FASD prevention and intervention.

The Culturally Competent Counselor

This TIP, like all others in the TIP series, recognizes the importance of delivering culturally competent care. Cultural competency, as defined by HHS, is…

“A set of values, behaviors, attitudes, and practices within a system, organization, program, or among individuals that enables people to work effectively across cultures. It refers to the ability to honor and respect the beliefs, language, interpersonal styles, and behaviors of individuals and families receiving services, as well as staff who are providing such services. Cultural competence is a dynamic, ongoing, developmental process that requires a long-term commitment and is achieved over time” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003, p. 12).

A critical element of this definition is the connection between attitude and behavior, as shown in the table on the next page.

Areas of Clinical Focus

In this chapter, you are invited to consider different methods and approaches to practicing prevention of an AEP and/or interventions and modifications for individuals who have or may have an FASD. The ten scenarios are common situations for behavioral health professionals and focus on:

- Intervention with a woman of childbearing age who has depression, is consuming alcohol, and may become pregnant (AEP Prevention)

- Examining alcohol history with a woman of childbearing age in substance abuse treatment for a drug other than alcohol (AEP Prevention)

- Intervention with a woman who is pregnant (AEP Prevention)

- Intervention with a woman who is pregnant and consuming alcohol, and who is exhibiting certain triggers for alcohol consumption, including her partner (AEP Prevention)

- Interviewing a client for the possible presence of an FASD (FASD Intervention)

- Interviewing a birth mother about a son who may have an FASD and is having trouble in school (FASD Intervention)

- Reviewing an FASD diagnostic report with the family (FASD Intervention)

- Making modifications to treatment for an individual with an FASD (FASD Intervention)

- Working with an adoptive parent to create a safety plan for an adult male with an FASD who is seeking living independence (FASD Intervention)

- Working with a birth mother to develop strategies for communicating with a school about an Individualized Education Plan for her daughter, who has an FASD (FASD Intervention)

| Attitude | Behavior |

|---|---|

| Respect |

|

| Acceptance |

|

| Sensitivity |

|

| Commitment to Equity |

|

| Openness |

|

| Humility |

|

| Flexibility |

|

This table originally appeared in TIP 48, Managing Depressive Symptoms in Substance Abuse Clients During Early Recovery ((SMA) 08-4353). The authors of this TIP gratefully acknowledge the authors of TIP 48.

Clinical Vignettes

Organization of the Vignettes

To better organize the learning experience, each vignette contains an Overview of the general learning intent of the vignette, Background on the client and the setting, Learning Objectives, and Master Clinician Notes from an “experienced counselor or supervisor” about the strategies used, possible alternative techniques, timing of interventions, and areas for improvement. The Master Clinician is meant to represent the combined experience and expertise of the TIP's consensus panel members, providing insights into each case and suggesting possible approaches. It should be kept in mind, however, that some techniques suggested in these vignettes may not be appropriate for use by all clinicians, depending on that professional's level of training, certification, and licensure. It is the responsibility of the counselor to determine what services he or she can legally/ethically provide.

1. INTERVENTION WITH A WOMAN OF CHILDBEARING AGE WHO HAS DEPRESSION, IS CONSUMING ALCOHOL, AND MAY BECOME PREGANT (AEP PREVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates how and why a counselor would address prevention of an AEP with a young woman who is being seen for depression.

Background: This vignette takes place in a college counseling center where Serena, 20, is receiving outpatient services for the depression that she's been feeling for about 4 months. In her intake interview, Serena has indicated that she consumes alcohol, is not pregnant, and is sexually active. She has had two prior sessions with the counselor, during which they have discussed Serena's general background, family interactions, social supports, and her outlook on school.

In today's session, they have been discussing her boyfriend, Rob. A therapeutic relationship has begun to form between Serena and the counselor, and the counselor would now like to explore Serena's alcohol use and whether it is a possible contributing factor in her depression. While doing this, the counselor will identify an opportunity to deliver an informal selective intervention to prevent a possible AEP.

Learning Objectives

- To illustrate that clients often have multiple issues that need to be addressed besides their primary reason for seeking counseling.

- To demonstrate a selective intervention (“FLO”) for preventing an alcohol-exposed unplanned pregnancy.

- To recognize that prevention of an AEP can be accomplished by eliminating alcohol use during pregnancy or preventing a pregnancy during alcohol use; often the most effective route is to prevent the pregnancy.

Vignette Start

The session is already in progress. Serena has been discussing how she and her boyfriend Rob tend to fight a lot, but she continues to spend time with him because they have fun at parties.

| COUNSELOR: | So, how long have you and Rob been together? |

|---|---|

| SERENA: | About 7 months. |

| COUNSELOR: | And you've said that the two of you are sexually active. |

| SERENA: | Yeah, I usually sleep over on the weekend, after the parties. |

| COUNSELOR: | Do these fights occur at any particular time? |

| SERENA: | Not really. When we're stressed, mostly, over school or work or whatever. Then I feel more depressed cuz we're fighting, and he gets upset because I'm depressed. It's like a circle. That's why we go to the parties, to unwind and forget about stuff. |

| COUNSELOR: | And then you tend to end up spending the night with him. |

| SERENA: | Usually. |

| COUNSELOR: | Are you using any protection, or birth control? |

| SERENA: | No. |

| COUNSELOR: | And during these parties, are you drinking? |

| SERENA: | Sure. |

| COUNSELOR: | About how many drinks do you have? |

| SERENA: | I don't really know. My cup's never empty, it just gets refilled at the keg. |

| COUNSELOR: | Are there other times when you drink alcohol? |

| SERENA: | No, it's really just at the parties. |

Master Clinician Note: Serena is presenting high-risk behavior by combining alcohol use and unprotected sex. The counselor seeks to identify the link between alcohol, unprotected sex, and pregnancy.

| COUNSELOR: | I know you're not expecting this, but if you were to find out right now that you were pregnant, how would that change things for you? |

|---|---|

| SERENA: | Oh lord, that would totally turn my life upside down. And Rob's. God, he'd freak. |

| COUNSELOR: | So, you do not want to get pregnant. |

| SERENA: | No, I definitely do not wanna get pregnant. |

Master Clinician Note: Serena has made it clear that she does not want to become pregnant, so the counselor shifts to addressing the gap between Serena's behaviors (being sexually active but not practicing safe sex) and her stated desire (to not get pregnant).

| COUNSELOR: | I understand, and I'm concerned about your health and what you want for your future. So, if you plan to keep attending these parties and being sexually active, then maybe we can talk about contraception. Did you know that half of all pregnancies in the U.S. are unplanned? |

|---|---|

| SERENA: | Wow. No, I didn't know that. |

| COUNSELOR: | It's true. It's possible that you could get pregnant, and the drinking could impact the health of that baby. Let's talk about how we can avoid those things. |

| SERENA: | Okay. |

The counselor gives Serena a pamphlet that describes effective contraception.

| COUNSELOR: | Would you be willing to read this? It's short, but it has good information. Perhaps we can go over it when we meet next week. |

|---|---|

| SERENA: | Okay. I thought I was here to talk about depression, though. |

| COUNSELOR: | Yes, absolutely, our first goal is to help you stop feeling depressed. And as you've said, you definitely don't want to have a baby, so I think it's important for us to discuss ways to avoid getting pregnant, so that that's not something that adds to your worries. |

| SERENA: | Oh, okay. I see what you mean. |

| COUNSELOR: | So next week I can answer any questions you have about that material, and then we can talk about some positive goals you want to lay out, like feeling less depressed, or fighting with Rob less, or not getting pregnant. Does that sound okay? |

| SERENA: | Yeah, thanks. |

Master Clinician Note: This vignette does not “solve” the issue of Serena's depression. However, as part of examining the possible causes, Serena has talked about a pattern of regular at-risk drinking, combined with unprotected sex. Because of this, the counselor—who by now has established a good rapport with Serena—has taken the opportunity to carefully include a selective intervention for preventing an AEP.

In an informal way, the counselor has used the steps of the “FLO” intervention discussed in Part 1, Chapter 1 of this TIP. During intake and again at this visit, Serena has indicated that she consumes alcohol and is sexually active. The counselor provides Feedback on these responses (by discussing the possibility of an AEP), then Listens as Serena indicates that she does not want to become pregnant. The counselor thus shifts the focus of medical advice to the Option of contraception and provides Serena with educational material.

At the same time, the counselor has not lost sight of depression as Serena's primary treatment issue. In this session, the counselor has laid the groundwork for continuing to discuss Serena's at-risk drinking and her problematic relationship with Rob as possible components of the depression, but in the context of positive goals that Serena can aim for (i.e., finding ways to feel less depressed, fight with Rob less, and avoid an unwanted pregnancy).

2. EXAMINING THE ALCOHOL HISTORY WITH A WOMAN OF CHILDBEARING AGE IN SUBSTANCE ABUSE TREATMENT FOR A DRUG OTHER THAN ALCOHOL (AEP PREVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates the value of asking about alcohol use in a female substance abuse treatment client of childbearing age, even though her primary drug is not alcohol.

Background: Chloe is being seen at an outpatient treatment center for methamphetamine abuse. The counselor has the health history that was provided during intake. It indicates that Chloe reports as non-pregnant, but is 28 (of childbearing age) and is sexually active.

The counselor wants to explore whether Chloe is using other substances, as well as screening for a possible mental health problem. Given that the client is sexually active, there is a risk of an unplanned pregnancy, therefore the counselor begins with alcohol.

Learning Objectives

- To emphasize the importance of probing for alcohol use even if it is not the primary drug.

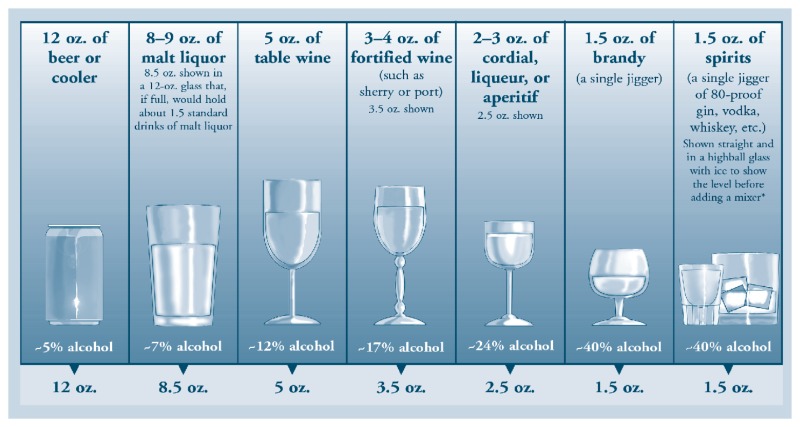

- To recognize that quantity of use is subjective. The use of a visual helps the client understand what a one-drink equivalent is.

- To recognize that if a mental health issue presents itself, it will need to be addressed concurrently.

Vignette Start

| COUNSELOR: | Hi, Chloe. |

|---|---|

| CHLOE: | Hey. |

| COUNSELOR: | Please have a seat. I have some questions that I would like to ask you, Chloe. You're in treatment for methamphetamines, correct? |

| CHLOE: | Yes. |

| COUNSELOR: | If it is okay with you, I would like to ask you first about your use of some other drugs. I would like to start with alcohol. Do you know how much alcohol you drink? |

| CHLOE: | You mean, altogether? I don't know. |

| COUNSELOR: | Okay, in an average week, how much alcohol would you say you drink? |

| CHLOE: | Well, usually I just drink enough to wash down my pills. |

| COUNSELOR: | What pills are those? |

| CHLOE: | The, whatayacallit, desoxyn. |

| COUNSELOR: | And what do you wash these pills down with? What kind of alcohol? |

| CHLOE: | Usually vodka. With some orange juice in it. |

| COUNSELOR: | And do you do this every time you take the pills? |

| CHLOE: | Not every time, but most times. |

| COUNSELOR: | Okay. And how much vodka do you drink to wash down the pills? |

| CHLOE: | One drink. |

| COUNSELOR: | Here, let me show you something real quick. This is a picture of different glasses that people tend to use for drinking alcohol. Which one do you use? |

Master Clinician Note: The counselor uses the visual below to help Chloe more concretely understand her level of consumption. However, this visual does not reflect every available drinking size or container, so any discussion of a standard drink should incorporate the client's personal experience (i.e., “If you don't see your glass on here, what do you use?”).

| CHLOE: | None of them. Well (Chloe indicates the 8.5 ounce drinking glass), that looks like what I use, but it's not all vodka. |

|---|---|

| COUNSELOR: | How much do you fill with vodka, and how much orange juice? |

| CHLOE: | About half and half. |

| COUNSELOR: | All the way to the top? |

| CHLOE: | Yeah, but with ice in it. |

| COUNSELOR: | Okay, so that's going to be about three to four ounces of vodka, and an ounce and a half of hard liquor is equal to one drink. So, it looks like you're having the equivalent of two to three drinks every time you wash down the pills. |

| CHLOE: | Hmm. I didn't know that. |

| COUNSELOR: | Is there any other time when you use alcohol? |

| CHLOE: | I may have some when I'm feeling bad. It takes the edge off. |

| COUNSELOR: | Can you tell me more about how you feel when you “need to take the edge off?” |

| CHLOE: | I just feel very upset, worried. Sometimes sad. |

| COUNSELOR: | That must be hard for you. About how often do you feel worried and/or sad? |

Master Clinician Note: The counselor expresses empathy for the client and how sad/worried she is feeling. This expression of empathy assists in establishing more of a caring relationship, so that further questions around alcohol use can be explored in a helpful manner. The counselor also explores more with the client about how she is feeling when she talks about “taking the edge off” to see what might be the result of her drug use and to see if she needs a mental health evaluation. A mental health evaluation might explore whether medication is indicated that could assist Chloe in reducing her alcohol use.

| CHLOE (laughs): | A lot. |

|---|---|

| COUNSELOR: | It must be difficult to feel so sad and worried a lot. Can I ask you a few more questions about this? |

| CHLOE: | Okay. |

| COUNSELOR: | Did you feel very sad or worried this week? |

| CHLOE: | Yeah. |

| COUNSELOR: | So, when you felt this way this week, did you need to use alcohol to feel better? Or, as you said, to take the edge off? |

| CHLOE: | (shrugs) Yeah, I had three or four drinks. |

Master Clinician Note: The counselor does not assume that the client is deliberately underestimating, but keeps in mind that clients may minimize when self-reporting alcohol use (Taylor et al., 2009).

| COUNSELOR: | Did you also feel like this last week? |

|---|---|

| CHLOE: | Probably. |

| COUNSELOR: | How about last month? Did you need to use alcohol to try to feel better then also? That would have been August. |

| CHLOE: | I'm sure I did. |

| COUNSELOR: | So Chloe, you would say that you're feeling sad and worried, and using alcohol to help you feel better, has been going on for quite a while, is that right? |

| CHLOE: | Yeah, most of this year. |

Master Clinician Note: Given the frequency of poly-drug use among clients in substance abuse treatment, this counselor did not assume that methamphetamine was the only substance that Chloe was using. Through some simple probing, the counselor has identified that not only has Chloe been drinking, she has been doing so at a high-risk rate. At a future time when dealing more specifically with the amount Chloe is drinking, the counselor might show her a chart with drinking frequencies to help Chloe see what level of drinking is defined as heavy and/or problematic for women.

Chloe has also talked about a pattern of self-medication. The reason or trigger for this may be depression; Chloe has said only that she drinks when she is “feeling like s&@*.” This will require further exploration. For now, the counselor knows that a potential co-occurring mental health issue, a co-occurring substance abuse issue, and prevention of a possible AEP should all be factored into the treatment plan.

3. INTERVENTION WITH A WOMAN WHO IS PREGNANT (AEP PREVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates that screening for alcohol use should be done at every visit with women who are—or are at an indicated likelihood for becoming—pregnant. Alcohol-exposed pregnancies occur in all demographics, regardless of socio-economic status, age, ethnicity, or marital status.

Background: April, 27, works full-time. She recently found out she is pregnant with her first child. She and her husband have relocated to a new city, and she is being seen at a private OBGYN office for the first time.

Learning Objectives

- To recognize that asking about alcohol use during the first visit only is not enough; screening should occur at every visit.

- To identify that a woman could begin drinking during the pregnancy if she is experiencing a relapse.

- To highlight there is no known safe amount of alcohol use during pregnancy.

Vignette Start

| 1st Office Visit | |

|---|---|

| PRACTITIONER: | Hello, I'm Dr. Johnson. I see on the chart that you are pregnant. Congratulations! |

| APRIL: | Thank you. |

| PRACTITIONER: | I have a number of questions that I need to ask you before the exam. |

Practitioner inquires about health history and eating habits, recommending an increase in fruit consumption.

| PRACTITIONER: | A few other quick questions. How much do you smoke per day? |

|---|---|

| APRIL: | I don't smoke. |

| PRACTITIONER: | That's good! How much coffee and water do you drink? |

| APRIL: | I have a cup of coffee in the morning, that's about it. I try to drink water all the time. I don't know how much I have per day. Probably a few glasses worth. |

| PRACTITIONER: | Okay, how often do you drink alcohol? |

Master Clinician Note: The practitioner has included alcohol as part of a general health exploration rather than asking the question by itself, which can make some clients nervous. Still, April looks a little concerned.

| APRIL: | I don't drink any alcohol. |

|---|---|

| PRACTITIONER: | Okay, that's good to hear. Not to worry, that's just a general question that I will be asking during all of our visits. There's no safe time, amount, or kind of alcohol to drink during pregnancy, so we recommend women not drink during their pregnancy. |

| 2nd Office Visit: | We pick up the conversation after the practitioner has again gone over the general health questions about smoking and level of intake of water and coffee. |

| APRIL: | I'm actually trying to drink more water now, and less coffee. I carry a water bottle around with me all the time. |

| PRACTITIONER: | Okay, that's good. How much alcohol have you had? |

| APRIL: | None, really. |

| PRACTITIONER: | Have you had any alcohol? |

| APRIL: | One glass. We were having dinner with some friends. |

Master Clinician Note: This interaction demonstrates the value of re-screening in relation to alcohol. April stated in the first visit that she does not drink. However, during this second visit, she has revealed that she does drink on occasion. It will be important for the practitioner to repeat the benefits of abstinence during pregnancy and probe for level of alcohol use, while remaining supportive and nonjudgmental.

| PRACTITIONER: | I see. Well, as we discussed at your last visit, no alcohol use during the pregnancy is the best policy. We just want to take the best possible care of your baby. About what size was that glass, would you say? |

|---|

Master Clinician Note: The practitioner can use a visual aid, as in the previous vignette, to help April understand how much really equals one drink. The practitioner has also repeated the importance of abstinence during the pregnancy, and tied the guideline specifically to the health of April's baby.

| 3rd Office Visit: | At this visit, April again indicates alcohol consumption, this time “a couple of drinks” at a dinner party. The practitioner explores further. |

|---|---|

| PRACTITIONER: | How many drinks did you have? |

| APRIL: | Well, my friend handed me a glass of cabernet when I arrived, because she said I would love it. I reminded her that I was pregnant, but she said a couple wouldn't hurt and that she had a few when she was pregnant and her kids were fine. |

| PRACTITIONER: | So, you drank the cabernet. Did you have any others? |

| APRIL: | Well, then I had some with dinner, too. I felt like I had been really good during the pregnancy, so I just decided to have a few drinks this one night. |

| PRACTITIONER: | So, you ended up having a few drinks that night. |

| APRIL: | Yes, but just that one time. And it was only wine. |

| PRACTITIONER: | I know that the temptation to have some drinks at a party or a celebration can be great, but there are a couple things to keep in mind. One is that science has shown that alcohol can harm the baby. We don't know yet how much alcohol consumption is too much, so it's very important to avoid all alcohol during the pregnancy. |

The practitioner pauses for the client to process what has been said.

| APRIL: | Okay. |

|---|---|

| PRACTITIONER: | Also, it's important to understand that any type of alcohol you drink can hurt the baby, not just certain kinds. Wine, hard liquor, beer…any beverage with alcohol in it. So it's important to avoid all of them during the pregnancy. |

| APRIL: | Gotcha. |

Master Clinician Note: Given that April has continued to drink even after her first couple of visits, the practitioner takes the educational process a step further this time, clearly noting that science has established a risk and that there is no “acceptable” form or amount of alcohol. A counselor or practitioner may also want to discuss the possibility of equipping April with some tools to help her abstain during the pregnancy (e.g., relaxation techniques, recreation, avoiding trigger situations such as parties). The need to continue to monitor April's alcohol consumption should be clearly noted in the medical record.

4. INTERVENTION WITH A WOMAN WHO IS PREGNANT AND CONSUMING ALCOHOL, AND WHO IS EXHIBITING CERTAIN TRIGGERS FOR ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION, INCLUDING HER PARTNER (AEP PREVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates a method for obtaining the alcohol history of a pregnant woman.

Background: Isabel, 30, has been referred to an outpatient mental health treatment center for feelings of depression. She is Hispanic, married, and pregnant (in her third trimester), and has one other child. The counselor and client have completed the intake process and Isabel has participated in the development of her comprehensive treatment plan. This is their third meeting. The counselor and Isabel agreed at the end of their last session that this would be about potential health risks with the pregnancy.

Learning Objectives

- To learn how to use a practical visual tool (a calendar) to more accurately and effectively identify client drinking patterns and possible triggers for alcohol consumption.

- To identify verbal cues that can indicate that a topic is becoming uncomfortable for a client, and apply effective techniques when a client becomes upset.

Vignette Start

| COUNSELOR: | Hi, Isabel. How are you? |

|---|---|

| ISABEL: | Fine, how you doing? |

| COUNSELOR: | I'm fine, thanks. When we met last, we finished working on your treatment plan. You have had a little bit of time to think about the plan now. Do you have any thoughts or concerns about what we developed? |

| ISABEL: | No, not really. |

| COUNSELOR: | How are you doing with the pregnancy? |

| ISABEL: | Pretty good. Things are going pretty well. |

| COUNSELOR: | Great. Now, at the end of your last visit here, we said we would spend part of today's session talking about alcohol use during pregnancy. You indicated during your intake that you drink socially, so let's talk about that a little more. Knowing about when and how much you drink will help us to see if there is any need to be concerned about any health issues for you or the baby. Is that okay with you? |

| ISABEL: | [Sounding a little concerned.] What do you mean “concerned about health issues?” I am not an alcoholic. |

Master Clinician Note: The counselor wants to reassure Isabel that she has not formed a negative opinion of her. The counselor now also needs to be aware that Isabel may try to minimize the frequency and amount of alcohol consumed so that she is not viewed as an alcoholic.

| COUNSELOR: | [Calmly and reassuringly.] I am sorry, Isabel. I wasn't trying to say that you have an alcohol problem. Nothing you have told me during our previous sessions would lead me to believe that you are an alcoholic or have a drinking problem. You said you only drink socially, correct? |

|---|---|

| ISABEL: | Yes. I don't drink every day or even every weekend. |

| COUNSELOR: | Good. That's just what I thought. I know, just from the short time we have been seeing each other, that you would never do anything to hurt your child. But, would you agree that drinking socially for one person might be different than drinking socially for another? |

| ISABEL | Of course. |

| COUNSELOR: | Alcohol can have an influence on individuals who are anxious, depressed, and even on women who are pregnant, and possibly their unborn child. That influence can depend on the frequency and amount of alcohol consumed. So knowing the social situations and how much you drink at those occasions will help us determine if you need to make any changes between now and when the baby is born. If it is okay with you, let's see if we can identify those situations. |

| ISABEL: | Okay, I'll give it a try. |

| COUNSELOR: | Thanks. That's great. So first let me ask you this: Normally, when you aren't pregnant, how often would you say you drink alcohol? |

| ISABEL: | Well, most of the time I'm not normally a drinker. |

| COUNSELOR: | Okay, that's good. When you do drink, about how much do you have? |

| ISABEL: | I can't really say. It depends. |

Master Clinician Note: The counselor wants to get an accurate picture of Isabel's drinking during pregnancy, so she brings out a calendar. The visual is helpful as it allows both client and counselor to put their eye contact elsewhere, which can contribute to the ease of discussion. The counselor explains that it also helps to trigger memory by looking at dates.

| COUNSELOR: | Okay, so let's start by figuring out when you first found out that you were pregnant. |

|---|---|

| ISABEL: | I went to Dr. Murphy's office and they did a pregnancy test. I had not had my period. I can look at the calendar, but I am pretty sure it was sometime in May. |

| COUNSELOR: | Do you think it was the beginning of May or the middle? |

| ISABEL: | It was the middle, and then I went home and told Marco. |

| COUNSELOR: | Ok, so you found out you were pregnant in the middle of May. [Counselor marks the calendar.] When did Dr. Murphy tell you your due date would be? |

| ISABEL: | Around December 22. |

| COUNSELOR: | Great, so we know you're in your third trimester now. [The counselor circles the third trimester with a colored pencil, then circles the other trimesters with different colors.] It looks like you probably got pregnant somewhere around the beginning of April. [The counselor also marks this on calendar.] Did your alcohol drinking change after you found out you were pregnant in mid-May? |

| ISABEL: | Yes, I pretty much quit drinking after that. But right before, around the beginning of May [points to calendar], Marco had just gotten a job and we went out with some friends. We went to party that one time, and I drank a little, but I don't think that would harm the baby. It wasn't a lot. |

| COUNSELOR: | You're doing great. Do you remember what you were drinking? |

| ISABEL: | I had one rum and Coke. Mostly Coke, with a little rum. |

| COUNSELOR: | Was that all? |

| ISABEL: | I had one wine cooler which I sipped for the rest of night. That wasn't too much, was it? |

Master Clinician Note: The counselor senses that Isabel is getting a little anxious about this line of questioning and tries to be reassuring and non-judgmental.

| COUNSELOR: | Two drinks in one night don't sound like a lot to me. I'm only asking because I want to help you do the best for the baby between now and the time you deliver. So let's see: It seems like you are saying that you mostly drink on special occasions. Is that right? |

|---|---|

| ISABEL: | Yes, those are the times I usually drink, and sometimes when Marco has friends over to watch a game I might have a beer or two. |

| COUNSELOR: | Okay. Can you remember any other occasions when you might have been drinking during your pregnancy? |

| ISABEL: | I drank a little on my birthday in July. |

| COUNSELOR: | Did you go out for your birthday? |

| ISABEL: | No. Marco surprised me when I got home. He made me dinner with flowers and wine and everything. |

| COUNSELOR: | He sounds very thoughtful. |

| ISABEL: | [Smiling, shrugs a little.] He can be. |

| COUNSELOR: | So, do you remember how much wine you had that night? |

| ISABEL: | I had maybe two or three glasses. I have read that drinking a little wine would not hurt the baby. I try to be aware not to do anything that would hurt my baby. I drank a little with my first child and he is healthy. |

| COUNSELOR: | I know that, Isabel. No mother would do anything on purpose to hurt her baby. I know how hard you're working to take care of yourself during the pregnancy, and that's really important. Did Marco drink with you on your birthday? |

| ISABEL: | Marco drinks all the time. He drinks beer every day. I'm sure that I'm okay, because you know I'm not like Marco. I don't come home and a have a six pack. |

| COUNSELOR: | Okay. So, you drank these two times before you got pregnant. And right about here is when you would have found out you were pregnant. [The counselor points to circled first trimester on calendar.] Are there any other days in these months that you can think of, or any events? |

| ISABEL: | [Pauses, squirms a little in her chair.] Well, there was one time Marco and I had an argument about the amount of time he spends with his friends. He goes out on Friday nights and drinks with his friends, doesn't come home sometimes until the next morning. He went out and I had some of my girlfriends over and I wound up getting drunk. I was so bad I was throwing up. I was embarrassed. I had to go to the bedroom and they had a bucket and they were saying “Isabel, are you okay?” But that's the only time I can think of. |

| COUNSELOR: | And what were you drinking then? |

| ISABEL: | We were drinking rum and Coke. |

| COUNSELOR: | Okay, do you know how many drinks you had? |

| ISABEL: | We were drinking and playing cards. I must have had three or four, at least. |

| COUNSELOR: | How many drinks does it take to make you feel high? |

| ISABEL: | It depends. A couple glasses of wine, or one rum and Coke, if it is strong. |

Master Clinician Note: The counselor is gradually asking more detailed questions about Isabel's alcohol use. Although Isabel claims not to be a drinker, a pattern of usage is emerging through the use of the calendar. Isabel is bringing up Marco often, so the counselor takes this cue and probes further about her husband.

| COUNSELOR: | It sounds like whenever you drink it has something to do with Marco. Are there times that you drink by yourself? |

|---|---|

| ISABEL: | No. |

| COUNSELOR: | Okay, so tell me about drinking with Marco. |

| ISABEL: | [Sighs.] It's just mostly because we're with friends and I like to do what everyone else is doing. I want to be social. I don't drink every day with him. He'll come home with a six pack and drink beer while he is watching TV or sports. He loves baseball and basketball. |

| COUNSELOR: | So he drinks when he comes home from work. Does he want you to drink with him? |

| ISABEL: | He'll offer me a beer now and then, ya know, but that's his thing. That's what men do. I have too many other things going on. I really drink just a little. I really don't think that I am doing anything that is going to hurt the baby. I don't want to fight with Marco about his drinking or his friends. I have to come here to deal with my other problems. |

| COUNSELOR: | Is Marco excited about the baby? |

| ISABEL: | [Relaxing a little at the change in subject.] Oh yeah. Very. I'm excited, too. We're looking forward to this. |

| COUNSELOR: | How do you think it's going to be with his drinking after the baby is born? |

| ISABEL: | I don't know. I doubt he will change. |

| COUNSELOR: | Are you worried about that? |

| ISABEL: | No, he's a good guy. [She sniffles and wipes her nose.] He really is. I know you probably think he's an alcoholic or something. That's not how it is. We're not like that. [She starts crying.] I love this baby. So does he. We're trying to take care of it. [Her crying continues, and she gets an anxious expression on her face.] |

Master Clinician Note: Isabel is becoming anxious, and is shifting the topic away from alcohol. This is a signal, or cue, to the counselor that the client is uncomfortable. The counselor needs to acknowledge what Isabel is feeling and be careful about how much further she probes on this issue during this visit.

| COUNSELOR: | I know you have a lot on your plate and I think you are handling it quite well. You did quite a bit in today's session, and you did very well. I would like to end this session and talk a little about our next session. Would that be alright with you? |

|---|---|

| ISABEL: | Sure. |

| COUNSELOR: | I heard you say you had read something that drinking small amounts of alcohol was okay for a pregnant woman. Is that correct? |

| ISABEL: | Yes, I read it on poster, I don't remember where. |

| COUNSELOR: | I would like to give you something to read. It's short. It's about what can happen when babies are exposed to alcohol before being born. I would like you to read it so we can discuss it in our next session. Is that okay with you? |

| ISABEL: | Sure. The more I know, the more I can protect the baby, right? |

| COUNSELOR: | Absolutely. |

Master Clinician Note: The mental health counselor is in a difficult position. Her use of the calendar helped to reveal a pattern of alcohol use by Isabel and her husband that exceeds what Isabel first admitted and is unsafe for the baby. It also helped to establish some of Isabel's triggers for drinking alcohol, which include her husband and being angry.

At the same time, discussing alcohol use and how it can hurt a baby can be an emotional topic for the mother. She is working hard to take care of her baby, and the topic of alcohol may have gone further than she is comfortable with. At the same time, it has been useful, as Isabel seems to be reaching a point where she has begun to question her use of alcohol during pregnancy.

This is a learning moment for the counselor. She can see the value of exploring alcohol use with her pregnant patients, but she also knows that, in the future, she can pay closer attention to verbal cues that indicate a client's discomfort; in Isabel's case, the changing of the topic and the repeated assertions that she doesn't think she has hurt her baby. The counselor should continue the session long enough to bring closure to the topic of alcohol use, while supporting the positive things that Isabel has done to take care of her baby. The door should be left open to come back to the topic of alcohol in future sessions.

If Isabel continues to show a pattern of alcohol use during the pregnancy, the counselor can help her identify other ways to deal with her anger besides drinking (stress management), and help her identify or find support systems in her life other than her husband if he is not being supportive of her abstinence during pregnancy (e.g., a pregnancy peer support group). If a mental health counselor does not feel comfortable addressing these issues, referral to a qualified substance abuse treatment counselor is advisable.

5. INTERVIEWING A CLIENT FOR THE POSSIBLE PRESENCE OF AN FASD (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: This vignette illustrates the clues the health care worker is receiving that suggest an impairment and possible FASD. A client with an FASD, with brain damage, will not receive the information from the worker the same way someone without FASD will receive it. The client may not have a diagnosis and may not immediately present as someone with a disability. There are a number of questions the worker could ask to determine whether they need to operate in a different kind of therapeutic environment with the client. The main goal of this vignette is for the health care worker to consider the possibility of an FASD, not to diagnose an FASD, which can only be done by qualified professionals. A woman who has an FASD is at high risk for having a child with an FASD.

Background: Marta is a single woman, 19, who recently had a baby, and is being seen at a Healthy Start center by a health care worker. This is the first time they are meeting. The health care worker's colleague asked her to meet with Marta as she knew that the health care worker was knowledgeable about FASD and was known as the office “FASD champion.” The colleague has begun to suspect that Marta may need an evaluation for FASD, as she has repeatedly missed appointments or been late, gotten lost on the way to the center, failed to follow instructions, spoken at inappropriate times, and has repeated foster placement and criminal justice involvement in her case history. The only information in the history about Marta's biological mother is that she is dead. The colleague wants the health care worker to conduct an informal interview to assess the possibility of an FASD.

Learning Objectives

- To learn how to identify behavioral and verbal cues in conversation with a client that may indicate that the client has an FASD.

- To learn how to apply knowledge of FASD and its related behavioral problems, in order to reassess clients with troublesome behaviors or concerns for factors other than knowing noncompliance.

Vignette Start

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Hi Marta, how are you? |

|---|---|

| MARTA: | Good. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Your regular counselor has asked me to meet with you today for a few minutes to ask you a few questions, if that's okay. [Marta nods in agreement.] Okay, so tell me how you got here today. |

| MARTA: | [Shrugs.] I took the #10 bus, then I got off and walked. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Where did you get off the bus? |

| MARTA: | Madison Avenue. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Did you know you could have taken the bus to Washington Street instead of Madison Avenue? Then you would have been six blocks closer. |

| MARTA: | [Shaking her head.] I didn't know that. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Do you want me to write that down for you? |

| MARTA: | Okay. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | [Writes down the information.] Here, you can keep this in your purse. [Hands Marta the piece of paper.] |

Master Clinician Note: Individuals with an FASD sometimes exhibit poor working memory. The health care worker is not assuming that Marta has an FASD at this point. However, if she does, it is unlikely that she will remember the information about the bus route, so the health care worker writes it down.

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Did you pay for your bus ride with cash or a bus card? |

|---|---|

| MARTA: | Today I paid with cash, but I don't always have it. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | When are the times when you don't have money? |

| MARTA: | Sometimes friends borrow it, or other people. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | What other people? |

| MARTA: | Well, like last time, a man on the corner asked me for money, so I gave it to him. Then I didn't have any for the bus. |

Master Clinician Note: Marta has exhibited a double “red flag” for an individual with an FASD; poor money management skills, and a lack of understanding of consequence (i.e., giving away the money without understanding that she then wouldn't be able to pay for the bus).

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Marta, I'd like to ask you a little more about some of the questions that you were asked when you first came here. |

|---|---|

| MARTA: | Okay, go ahead. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | You told us that your mother is not alive. How old was she when she died? |

| MARTA: | Twenty-five, I think. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | How old were you when she died? |

| MARTA: | Four. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | I'm very sorry to hear that you've lost your mother. |

| MARTA: | [Very matter-of-factly.] I didn't lose her. She died. |

Master Clinician Note: Marta is exhibiting very literal interpretation of language, which is common among individuals with an FASD.

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | You're right, that's what I should have said. That was probably a hard time for you. [Marta nods.] Did you know much about her? |

|---|---|

| MARTA: | [Shakes her head and shrugs.] Not really. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Do you know if she ever had any kind of problem with alcohol? |

| MARTA: | Like, being an alcoholic? |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Yes. |

| MARTA: | [Shrugs.] I heard she drank, yeah. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Do you know if she drank alcohol while she was pregnant with you? |

| MARTA: | I don't know. [Pauses for a moment.] That's a weird question. Why are you asking that? |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Did the question make you uncomfortable? Sometimes when women drink during pregnancy their kids end up having extra challenges. Do you know what I mean when I say challenges? |

| MARTA: | Sure. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Can you give me an example? |

| MARTA: | [Shrugs]. I don't know. |

Master Clinician Note: Marta has stated that she understands when really she doesn't. Any young person might do this, but it is especially common for individuals with an FASD. Checking for cognition is important with clients that have or may have an FASD.

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Needing extra help in school is an example of a challenge. |

|---|---|

| MARTA: | Right, okay. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Is it okay to ask a few more questions? |

| MARTA: | Yeah. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Thanks. This will only take a couple more minutes, I promise. How about you? Do you drink alcohol at all? |

Master Clinician Note: Because this is an interview to see if there is reason to believe that Marta has an FASD, the counselor is probing to see if perhaps Marta's baby was also exposed to alcohol before birth.

| MARTA: | No, I don't like the taste of it. |

|---|---|

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Me neither. So, you didn't have any alcohol while you were pregnant? |

| MARTA: | No, my foster mom and dad told me not to drink or smoke while I was pregnant. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | That was very good advice. Tell me, where did you live when you were growing up? |

| MARTA: | First with my aunt, then lots of places. I was in foster care. |

Master Clinician Note: It is not unusual for individuals with an FASD to no longer be in the care of their parents, and to have been placed multiple times in foster care.

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Did you like school when you were growing up? |

|---|---|

| MARTA: | [Looking down.] Umm… I guess it was okay. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | What classes did you like? |

| MARTA: | I liked art. And I liked Ms. Norton. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Who was Ms. Norton? |

| MARTA: | Ms. Norton was in the resource room. |

Master Clinician Note: Time spent in the “resource room,” while not a clear-cut clue, is certainly a strong indicator that the child was identified in school as having special needs. This is often the case with children who have an FASD. The counselor could further explore by asking a follow-up question like “Did you ever have extra help with your school work?” or “Did you ever have special classes or tutoring in school?”

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | How many students were in the class with you? |

|---|---|

| MARTA: | Five, including Eddie. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Who's Eddie? |

| MARTA: | [Laughing a little to herself as she remembers.] Eddie is the kid that I used to get in trouble with all the time. He was always coming up with ideas. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | What do you mean when you say Eddie “came up with ideas?” Can you give me an example? |

| MARTA: | Well, like, one time we were walking home from school, and he saw a bike in someone's yard that he really wanted. So he told me to go get it for him. I did, but the man who lived there caught me and called the cops. |

| HEALTH CARE WORKER: | Did you realize that taking the bike could get you into trouble? |

| MARTA: | I had a feeling. I wasn't sure, but I wanted Eddie to keep liking me. |

Master Clinician Note: Involvement in “trouble” or crime as an unintentional secondary participant is an FASD “red flag,” particularly when the motivation is social (i.e., to make friends).

Master Clinician Note: Marta's case/vignette is oversimplified. In a matter of minutes, she has exhibited a handful of behavioral clues that suggest that she may have a disability. Not all individuals who may have an FASD will be this easy to ‘spot.’ This conversation is provided simply as a way to learn how such “red flags” might come up in conversation with a client. By identifying these red flags, which are particularly common in individuals with an FASD, the health care worker will be able to manage the case in a way that better suits the needs of the client, and can make a better-informed decision regarding the need for a more complete FASD diagnostic evaluation. Additional probing questions that could be asked include the following:

- How much alcohol did your mom drink when she was pregnant?

- Think about when you were a child. How did you do in school?

- Do you ever have trouble keeping appointments? How do you do with telling time?

Refer to Part 1, Chapter 2 for guidance on referring a client for a formal FASD diagnostic evaluation, and for strategies and treatment modifications that will improve treatment success with an individual who may have an FASD.

6. INTERVIEWING A BIRTH MOTHER ABOUT A SON WHO MAY HAVE AN FASD AND IS HAVING TROUBLE IN SCHOOL (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: Counseling professionals in mental health or substance abuse treatment may avoid talking to a female client or family member about their alcohol use during pregnancy, either to avoid communicating any shame or judgment to that individual, or out of a lack of knowledge about FASD. This case illustrates a scenario where such a discussion may prove fruitful, and the sensitivity required when starting the discussion.

Background: The vignette begins with a community mental health professional talking to Dixie Wagner, 35, about the behavior of Dixie's 7-year-old biological son, Jarrod. (Jarrod is not present at this session.) Jarrod is in trouble again for hitting another child, and this is causing distress for the mother that the mental health professional wants to address, which leads into a discussion of FASD.

Learning Objectives

- Cite methods to help the caregiver clarify the child's issues and discover why the child is having problems.

- Specify skills needed to follow the caregiver's lead in asking probing questions.

- Explore the negative perceptions surrounding prenatal alcohol exposure, and examine how lack of knowledge or fear of shaming may interfere with asking the right questions.

Vignette Start

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Dixie, we talked briefly on the phone about Jarrod's school issues. It sounds to me like you are concerned for him. Today I'd like to hear more about your concerns, and then we can work from there. How does that sound? |

|---|---|

| DIXIE: | Yes, that's fine. You're right, I'm very concerned about him. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Is it okay that we talk about the kinds of behaviors that led to Jarrod hitting a fellow student? Was the student a friend of Jarrod's? |

| DIXIE: | That is exactly what's so disturbing about this situation; it was someone I thought was a good friend, a kid named Garrett. Jarrod looks up to Garrett and talks about him all the time. I was excited that he wanted to be friends with Garrett. I was very surprised to get a call from the principal. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | You're right. Friends are so important for all children this age. Has Jarrod been having problems with his peers? |

| DIXIE: | [Sighs]. He's always had a hard time getting along with kids his own age. He starts off happy and friendly. He wants everyone to like him. Sometimes I think his enthusiasm might be too much for some kids. Sometimes he says such crazy things. I don't know if he thinks the kids will laugh at what he says or if he is really being serious. Slowly I can see the kids moving away from him. It breaks my heart. He ends up playing by himself. He really wants everyone to like him. He'll talk to anyone! We always say Jarrod has never met a stranger he didn't like. I worry a little that he'll listen to the wrong person when he gets older. Most of the time he's just so sweet and loveable. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Okay, so what I'm hearing is that Jarrod has been having problems making and keeping friends his own age, although he really wants to have a friend. Is that right? [Dixie nods.] How about in the school setting? How do you think he is doing in class and with his school work? |

| DIXIE: | Well, he's been labeled a “talker” in class, and we've gotten plenty of notes from the teacher because Jarrod likes to chat with his neighbors and that annoys them sometimes, and the teacher. He has a lot of energy, and sometimes loses focus on his work. He can get frustrated, and may have a hissy fit at school when he doesn't want to do his work. He likes to do a good job. Sometimes he just won't finish his work. So the teacher will send it home for us to do with him. Every night we sit down and spend a lot of time on homework, but that usually ends up in Jarrod fighting and yelling at us. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | So, Jarrod generally has a hard time focusing and sitting still. These hissy fits, as you call them, how many of these will he have in a typical school day? Can you tell me a little more about that? Are you noticing any consistent struggles? |

| DIXIE: | I guess he's had several since starting school this year. The hissy fits are like toddler temper tantrums. I can't believe he is still having tantrums. We never really know why he has them, especially at school. I know he leaves every day happy to be going to school, but when he gets home he's tired and cranky, and very angry. He doesn't know where his homework is in his backpack. This leads to raised voices, either me or my husband. The teacher always tells us Jarrod was given the homework, so he must be deliberately misplacing it. If we do find the homework assignment, Jarrod will sit and work really hard for awhile, but then he starts to whine and cry that he is tired and doesn't remember what the teacher told him that day. My husband and I review his spelling words with him every day. He sits and really tries hard to remember them. But he never passes the test on Friday. We spend lots of time with him on his homework. It's like we have to re-teach him everything he learned from the day. Many times it ends in a hissy fit. It's not like we don't help him. We've done this with him since he was in first grade. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Jarrod sounds like he is facing some challenges with his school work. Are there other times or activities when he struggles? |

| DIXIE: | Well, when he gets off the bus in the afternoon, he is out of control. He runs around, bumping into furniture and screaming. Sometimes he will knock down the dog. I am sure he doesn't mean to hurt the dog, though, because he really loves it. The teacher says he has trouble standing in line for lunch, and pushes the other students next to him. She also says he has a hard time on the playground for recess. He prefers to stay inside with her. And about 2pm every day, Jarrod gets very sleepy. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | I see. Is he getting enough sleep? |

| DIXIE: | We start the bedtime routine about 7:30, right after dinner. The kids will take showers, brush their teeth, and then we'll read a book together. We struggle to get Jarrod to brush his teeth. He hates taking a shower, but once the water is in the tub, he loves taking a bath. Everyone gets a chance to pick a book when it's their turn. Jarrod always picks a picture book about Kermit the frog. But when it is time to go to bed, Jarrod is wide awake, talking or playing his video games. We've had to put him in his own room so my other children can go to sleep. Jarrod is up before my husband, usually before 5am, because he's never needed much sleep. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | So what I am hearing is that you and your husband have set up a nighttime routine for all the children, but Jarrod has a hard time with the routine. It sounds like Jarrod is only getting a few hours of sleep at night. This may be a reason why Jarrod is having problems in school, since he is tired, but I would like to hear more from you. What else is worrying you? |

| DIXIE: | This isn't school-related, but that boy can't keep his room clean! I run a tight ship, and an unmade bed is not welcome. He can never find anything. I raise my voice, and still no results. My other kids listen to me. I have no idea why Jarrod disobeys me all the time. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Can you describe a typical room-cleaning episode? |

| DIXIE: | I'll say “Did you clean your room?” and he says “Yes” and then I'll go and check and nothing is put away. There are clothes on the floor. Dirty and clean clothes will be in his dresser drawers. The bed is unmade. He'll leave wet bath towels on the floor. And there he sits playing a video game. Nothing is done and he still says “Yup, it's clean!” He just doesn't listen. Sometimes I punish him. That doesn't work, either. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | That can't be easy, and I can see where that could be frustrating for you and your husband. Do you think it's a case of Jarrod not having the organizational skills needed to keep his room clean, or that he doesn't understand what you're asking him to do? |

| DIXIE: | I think he understands, he's just resisting. I know he can do it, but usually not until I stand over him and make him do it, one thing at a time. It's exhausting. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Well, That sounds like a lot of kids Jarrod's age. But what I'm getting at is when you break down the specific tasks for Jarrod—one thing at a time, like you say—he does what he's told and does it correctly. Is that right? |

| DIXIE: | Yes, we have found that there isn't a better kid when you work with him one-on-one. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | You're providing me with a lot of needed detail. Thank you. Knowing his behaviors out of school really does help me understand how we might be able to help him in school. I'd also like to follow up on something you mentioned earlier, about Jarrod's friends. How is he with kids his own age, besides Garrett? |

| DIXIE: | Besides the kindergarten twins who live next door, Jarrod has no one to play with. We tried to get him into soccer, but he ran after the soccer ball no matter what side had it and the kids made fun of him. We tried cub scouts with my husband helping out as den leader, but Jarrod would be very bouncy and talkative, grabbing the other kids' project, sometimes breaking them. The kids would be polite, but eventually started to shun him. Eventually he would go off by himself and play with a toy. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | This must be hard for you and your husband. |

| DIXIE: | We were told last year that Jarrod was immature for his age, but the teacher said boys tend to mature later than girls. The teacher wanted to wait and see if Jarrod matured over the year before we did any official school testing. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | So, let's recap what we have talked about. Jarrod tries to be social and verbal, is trusting, and wants to be a good friend. He also has trouble cleaning his room, staying on task, and doing his school work, but when he does sit down for homework, he can be very diligent in getting his work done. Then there may be some sensory issues, like brushing his teeth or taking a shower, and the bus tends to be a problem. Of course, we cannot forget the fight with Garrett. Out of all these things, I don't see a child with an aggressive nature. What I am concerned about, though, is that Jarrod might be facing some difficulties that will lead him to get into another fight. |

| DIXIE: | This isn't making sense to me. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Well, I don't have a real clear picture yet. However, one of things that could be at work is that Jarrod could have some cognitive issues that are creating differences in the way he processes information. These deficits can occur for a whole range of reasons. Sometimes children are born with them, and as they grow, their brains are different from most kids. |

| DIXIE: | You mean like ADHD? We've had people suggest ADHD before. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | ADHD may be one issue, but other things could be at work, too. Is it okay that we talk about before Jarrod was born? This is something that I've asked some of my clients before, and it may be helpful here, as well. I'd like to ask about Jarrod's birth, and when you were pregnant with him. It will help us understand Jarrod's environmental background. Were there any complications during your pregnancy with Jarrod? |

| DIXIE: | No, everything was fine. In fact it was a pretty easy pregnancy. I didn't have much morning sickness. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Would you say that you planned your pregnancy with Jarrod? |

| DIXIE: | No, not really. He's our third, and we weren't really planning on a third. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Now, many pregnancies are unplanned. About half in this country, in fact. Were you pregnant for awhile before you knew? |

| DIXIE: | Yeah, I found out kind of late. [Starts to become defensive.] But I had a good doctor, and good prenatal care. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | What did your doctor tell you about the use of alcohol during your pregnancy? |

| DIXIE: | My husband and I are social drinkers, but we always have been. I don't smoke. I drank during my other pregnancies. My doctor even told me to do it sometimes, because I get really stressed out and it's how I used to relax. I really think you're way off here. |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Your doctor told you that the occasional drink was okay? That it would relax you? |

| DIXIE: | Yes, he did, and why would he say that if it wasn't true? He's a pediatrician, for god's sake. Where is this going? Are you saying I did something wrong to hurt Jarrod? |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | No I do not think you would do anything to hurt Jarrod. Some doctors still give that advice, even though the evidence now suggests that alcohol can harm a fetus. It won't necessarily harm every fetus, but it can hurt some. I recognize that this is hard to talk about. I only want to explore the possibility. We both have the same goal, to help Jarrod. He has exhibited a pattern of behavior that makes an FASD something worth examining, even if it's just to rule it out. Do you know about FASD? |

| DIXIE: | [Sits forward in her chair, holding up her hands in a defensive manner.] So, wait. What you're saying is that I drank alcohol and hurt Jarrod while I was pregnant. Is that it? |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Only experts can determine whether a person has an FASD. Changes in the brain due to alcohol can only be identified by certain professionals, but what I do suggest is that we start to look at why Jarrod might be experiencing some of the problems that you and his teacher have identified. I am seeing a pattern of behavior that may suggest an FASD. We all want the best for Jarrod, and knowing what is happening in his head may help all of us meet his needs. |

| DIXIE: | [Leans back, crossing her arms, more relaxed but still wary.] What is this stuff, FASD? |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | It stands for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. See, alcohol is an environmental factor that can affect a developing fetus. I mentioned alcohol because some women are unaware of the effects that alcohol can have on an unborn baby. Scientists refer to the effects of alcohol on the fetus as FASD. |

| DIXIE: | I've never heard of it. Are you saying you think Jarrod has that? [Sits forward in her chair; tears well up in her eyes.] What you're saying is that I drank alcohol and changed Jarrod's brain while I was pregnant. Is that it? This is my fault? |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | I'm not leaping to that conclusion. If Jarrod does have an FASD, there is no blame here. I just think it's worthwhile to discuss the possibility, because it may help your son, which is what we both want. |

| DIXIE: | [Sits back in her chair and slumps a little.] Yeah, I wanna help him. I want nothing more. My husband and I have done everything we can. [She sniffles some more and shakes her head, considering; the counselor offers a box of tissues.] This has been so hard. It's been going on so long. We've seen so many doctors, and heard so many diagnoses, and no one's ever right. Nothing works. But no one's said anything like this before. And when you sit there and tell me that this might all be because I had some drinks while I was pregnant… [She sniffles some more.] |

Master Clinician Note: It's important at this point for the mental health professional to respond to the fact that the client is feeling blamed and becoming agitated.

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Then I have to apologize to you. If that's what you're feeling, then I'm to blame, not you. I haven't done my job properly. It's incredibly important to me that you understand that my only goal is to work with you to identify a potential root cause for the problems that Jarrod having, because it's clear that his situation is causing you distress. That's all I want to do. There are many cases of FASD. Jarrod would not be the first or the only one. No mother on earth does anything to intentionally hurt her baby. I know you certainly didn't. I have a child of my own. I know the feeling of being a mother, and it's very, very clear to me how much you love your son. |

|---|---|

| DIXIE: | I just… I don't even know what to say. I feel like you're pointing a finger at me. [She is angry, beginning to cry.] You're in mental health. No offense, but what do you know about medicine? Or about my son? About how much I love him? Or about what we've been through? I can't even understand that you're sitting there saying I did this to him. I mean, I hear your “no blame” crap, but I'm feelin' real blamed right about now! |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Well, like I said, I do apologize if that is how you feel. Maybe we just need to rule out FASD. If it happened, you were going on the advice of your doctor. Would it be alright if we focused on what you want to do next for Jarrod? |

| DIXIE: | [Waving her hand to stop the counselor.] What's it called again? |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. FASD. I can give you a pamphlet that talks about the basics of it. |

Master Clinician Note: It is advisable to provide FASD information that does not include pictures, particularly of children with prominent facial dysmorphology (e.g., thin upper lip, smooth philtrum). These facial characteristics are present in only a small percentage of children who have an FASD, and if the client's child does not resemble the children in the pictures, this may enable the client's desire to believe that their child can't possibly have an FASD.

| DIXIE: | [Taking the pamphlet.] So I should read this? |

|---|---|

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | Yes, it would be good if you and your husband both read it and discussed whether you think it describes Jarrod's situation. |

| DIXIE: | I still say you're wrong. But, what if it does? What happens then? |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | To start, I think you could begin the process for the school to start testing Jarrod for a learning disability. There are several tests that could help them understand the best way to teach Jarrod so that he doesn't get so frustrated. There are a few pieces of the testing that you will have to complete, like his developmental history, when he walked and talked, things like that. I think you should also look at doing another test for ADHD. In the meantime, we can set up another appointment to talk about FASD, possibly with your husband, as well. And if the two of you are okay with it, I can help you access a more complete evaluation. |

| DIXIE: | Where does that happen? |

| MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL: | It may be best to complete the assessment with a developmental pediatrician at the local hospital. I am sure that doctor will want to see the test results from school. If you like, there is a support group for families called the Circle of Hope. I could give you the phone number or e-mail address for them if you need someone else to talk to who has been through this. How would that be? |

Master Clinician Note: Although the mental health professional makes repeated attempts to assure Dixie that she does not need to feel blame about the possibility that Jarrod has an FASD, Dixie has still become upset. This is a very natural response, and counselors should be prepared for birth mothers to feel as though they are being ‘blamed’ for their child's condition when FASD is discussed. However, many pregnancies are unplanned, some doctors do still recommend a glass of wine as a way for a pregnant woman to relax, and many women do not realize until well into their first trimester that they are pregnant. The mental health professional utilizes these realities as a way to reassure Dixie and disconnect her from a sense of guilt and consistently reiterates their shared goal, to find the best way to help Jarrod. She also effectively coordinates care by putting Dixie in touch with additional testing and offering a support group number.

7. REVIEWING AN FASD DIAGNOSTIC REPORT WITH THE FAMILY (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: The purpose of this vignette is to provide counselors with guidance on how to review a diagnostic report (or Medical Summary Report) with family members of a child who has been just diagnosed with FAS.

Background: The client, Jenine, is the caregiver of her grandson, Brice. Jenine is meeting with a counselor from the Indian Health Service to review Brice's Medical Summary Report for the first time. In a prior session, Jenine confided that she felt overwhelmed. Knowing how detailed a Medical Summary Report can be, the counselor suggested that Jenine bring trusted family members and elders to this session. Together they arranged for Jenine's sister, aunt, and an elder to attend.

Learning Objectives

- To recognize that clients will need support after an FASD-related diagnosis.

- To identify how to help the client prioritize the child's and the caregiver's needs.

- To recognize that the client will need to be educated to understand that the child's behavior problems are due to damage to brain caused by prenatal alcohol exposure.

Vignette Start

| COUNSELOR: | Welcome, everyone. It is so good for Brice that you could be here. I am very happy to try to answer all of your questions today. We'll go through the basics, so that we can work on what is best for Brice. Does that sound good? |

|---|---|

| JENINE: | Yes. |

| AUNT: | Yes. |

| ELDER: | Yes. |

Master Clinician Note: The counselor is listening to everyone in order to validate the feelings and concerns of all individuals attending the session.

| COUNSELOR: | As I mentioned when you arrived, I am so glad that each of you are here today to support Jenine through this diagnostic process. Together, we can come up with a plan and move forward from there. The plan will build on Brice's strengths, as well as the diagnosis. We'll get started today, but it will take more meetings and community support to understand this diagnosis. A lot of detailed information can be overwhelming, but again, together, we will work through this process. |

|---|---|

| JENINE: | Okay. |

| COUNSELOR: | Before we review the report, let's talk about FAS. What kinds of things have you learned about FAS? |

| JENINE: | I have been reading a lot on the internet. |

Master Clinician Note: It is advisable for the counselor to caution the client and all attending the session that the quality and reliability of online information about all forms of FASD varies. She should provide the client with a reading list of up-to-date sources, but advise them to put it down when they need a break to avoid feeling overwhelmed.

| COUNSELOR: | Okay, I like the internet as a source of information because there can be some helpful sites. At the same time, not all internet information is up-to-date. Here is a list of three Web sites that I recommend. They are updated all the time. They're really the best place to start. The first site publishes some basic facts and I'd like to review that with you all for a few minutes. |

|---|

Master Clinician Note: The counselor can now review the report with Jenine and her support persons. The counselor can use the review to assess the knowledge level of the client and her sister and elder, in order to determine how much education and support will be needed throughout the process. It is also advisable to inquire about other family members (grandparents, brothers, sisters, aunts and uncles, extended family) to assess how they will feel about the child's disability and to gain insight into cultural differences.

A sample Medical Summary Report can be viewed at the Web site of the Washington State FAS Diagnostic & Prevention Network (FAS DPN): http://depts.washington.edu/fasdpn/pdfs/4-digit-medsum-web-2006.pdf.

After completing the review, the counselor should focus on Brice's priority problem area, as well as the most significant need(s) of the caregiver.

| COUNSELOR: | Okay, now that we've worked our way through the report, we need to focus on the number one area where Brice is having problems. Is that in school or at home? |

|---|---|

| JENINE: | Both, but I can handle home. School is getting out of control. I hope that this diagnosis gets him the help he needs. |

| COUNSELOR: | Well, I know that a diagnosis is not always the pathway to services that we expect. But what I did see in the report was a clear description of Brice's speech and language difficulties, so I think that we can get him the speech therapy services that will help in school. |

| JENINE: | That would be wonderful. Brice stutters, and really has a hard time coming up with the right word on the spot. |

| COUNSELOR: | Okay, then let's make the top priority for Brice to get services and therapy for speech. Does that sound like the best place to start? |

| JENINE: | Yes, let's do that. |

| AUNT: | I will help. |

| ELDER: | We will help, too. |

| COUNSELOR: | Now let's discuss a top priority for you, Jenine. I want to check in with your stress level. If you are stressed, then it will be hard to be truly supportive for Brice. And it is my experience that parents and caregivers of children who have special needs do deal with burn-out. |

| JENINE: | Yeah, that sounds like me. |

| COUNSELOR: | Then since that's the case, let's use a couple of sessions to make a plan. If we have any medical questions, I can consult with a pediatrician to try to get those answered for you. Next, we'll get the speech therapy going for Brice. |

| JENINE: | Okay. How am I going to pay for all of this? All of these services? |

| COUNSELOR: | I know some of that is being paid through your insurance company. I'm more or less the case manager for Brice, so anything not covered, we'll work together to address how those things will get paid for. |

| JENINE: | Okay. Now, what's going to happen in school now, with this diagnosis? |

Master Clinician Note: Even though answers to these questions cannot all be provided immediately, the counselor assures the client that they will work together to establish plans to address them.

| COUNSELOR: | I think that it will be a process, and that will be the focus of our time next week. We'll want to think about how you can best approach the school to get Brice's special needs met. We'll also discuss how to talk to your family and friends as well as his teachers about FAS. |

|---|---|

| JENINE: | Okay. |

| COUNSELOR: | One thing we can definitely do today is make a list of Brice's strengths. It's very important that our plan for helping him focuses not just on his diagnosis but also on his positive abilities. Can you all help me with that? |

| JENINE: | Sure. He has a lot of wonderful qualities, he really does. |

| COUNSELOR: | I know he does. We're going to build on those. So, let's recap. Our first priority is to get the process started on Brice's speech therapy. We also need a plan to help you, Jenine, when you're feeling burned out. We want to talk about payment for services. And we want to address what this diagnosis means in terms of special needs at school. Does that sound right? |

| JENINE: | Yes. |

| AUNT: | Yes. |

| ELDER: | Yes, it does. |

| COUNSELOR: | Good. I'm writing all this down, and I'll give everyone a copy. And we'll set up a time for our next meeting. Let's pick a time that works for everyone. |

Master Clinician Note: A diagnosis of any form of FASD can be overwhelming for a family. Although this vignette lacks specifics, the overarching theme of importance is that the counselor is positive, is willing to work with the family to make a plan to address any areas of concern, and is available to help them through the process. For families and caregivers of an individual with an FASD, having this navigational assistance can be tremendously helpful and relieve much of the stress that can go along with caring for such an individual. In addition to addressing the areas identified by the family as priorities, it will be important in future sessions for the counselor to:

- Consistently point out the child's positive attributes;

- Recommend a specific support group for the family, if available;

- Emphasize the need for respite care; and

- Ask the client about ways to involve the child in an area of interest, like music or sports or art. This can provide a ‘break’ for both the child and the caregiver.

8. MAKING MODIFICATIONS TO TREATMENT FOR AN INDIVIDUAL WITH AN FASD (FASD INTERVENTION)

Overview: The purpose of this vignette is to demonstrate how to modify treatment plans for a client with an FASD.

Background: The client, Yvonne, is an adolescent female with a history of truancy and fighting. She has been mandated to counseling for anger management, and has missed her last two appointments. When the counselor phoned her about the missed appointment, Yvonne's mother suggested that Yvonne may not be taking her medication, and hinted that Yvonne may be depressed.

Learning Objectives

- To adjust expectations regarding age-appropriate behavior, since individuals with an FASD may be adult-aged by calendar years, but are much younger developmentally and cognitively.

- To demonstrate the value of collateral information and how to ask an individual for consent.

- To demonstrate the importance of seeking involvement from parents and caregivers.