NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Alliance (UK). Endometriosis: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2017 Sep. (NICE Guideline, No. 73.)

11.1. Pharmacological management

11.1.1. Analgesics

Review question: What is the effectiveness of analgesics for reducing pain in women with endometriosis, including recurrent and asymptomatic endometriosis?

11.1.1.1. Introduction

Pain is the most debilitating and common symptom of endometriosis. Endometriosis may cause cyclical pelvic pain, typically during menstruation, and often starting a few days before a woman’s period. Referred pain to the back and legs is common. Apart from acute pain during menstruation, women may also experience non-cyclical pain, deep pain during sexual intercourse, and pain associated with bowel and bladder functions. For many women, pain becomes persistent or chronic.

Most women who experience menstrual pain and who would like pharmacological analgesia will buy over-the-counter medications or be prescribed simple analgesics such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), for example, ibuprofen, naproxen or aspirin. Mefanamic acid, another NSAID, is also commonly chosen for menstrual pain. For moderate to severe pain, weak opioids such as codeine are often used but the side effects of these are often limiting; constipation in particular may aggravate endometriosis symptoms. Stronger medication such as morphine is also prescribed if the pain is severe and does not respond to other treatments.

Symptomatic management of pain using analgesics is thus very important for women with endometriosis. Because of disease recurrence and potential chronicity of pain, women need access to analgesics throughout a lifetime living with endometriosis.

11.1.1.2. Description of clinical evidence

The objective of this review is to determine the clinical and cost effectiveness of analgesics in reducing pain in women with endometriosis.

For full details, see review protocol in Appendix D.

One study was included (Kauppila 1985) that used a crossover design to evaluate the effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) compared with placebo in 24 women with ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ painful menstrual periods secondary to endometriosis. Endometriosis was diagnosed by pelvic examination, or by visualisation (for example, laparoscopy or laparotomy). One group of women received naproxen tablets for 2 menstrual cycles and then crossed over to placebo for 2 further menstrual cycles. The second group received placebo for the first and second menstrual cycles, then crossed over to naproxen sodium for 2 further menstrual cycles. Both groups received 275 mg naproxen tablets (1 or 2 tablets 4 times a day).

Results are presented from the first treatment period for 20 women who used a questionnaire immediately after each menstrual cycle to self-record outcomes of pain severity, use of supplementary analgesia and unintended effects from treatment. For severity of pain a score (range 1–3) was used where ‘mild improvement’ was scored as 1, ‘moderate improvement’ was scored 2 and ‘excellent relief’ was scored 3. It is not clear how the questionnaire was developed or validated.

No evidence was identified for the critical outcome of quality of life or for the important outcomes of effect on daily activities, absence from work or school, number of women requiring more invasive treatment and participant satisfaction with treatment.

Evidence is summarised in the clinical GRADE evidence profile below Table 53. See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix F, study exclusion list in Appendix H, forest plots in Appendix I, full GRADE profiles in Appendix J and study evidence tables in Appendix G. Summary of included studies

A summary of the studies that were included in this review are presented in Table 52.

11.1.1.3. Clinical evidence profile

The clinical evidence profile for this review question (NSAIDs for treatment of endometriosis) is presented in Table 53.

11.1.1.4. Economic evidence

No economic evidence was found on the use of analgesics in women with endometriosis.

Consequently, data from NICE CG173 (neuropathic pain) was used to inform an economic model that is described in more detail in Appendix K.

The economic cost of analgesics is very difficult to quantify. Although the drugs and the dosing regimen are normally very well understood, compliance and indirect costs (such as additional GP visits) can create uncertainty over the ‘true’ cost of prescribing one drug over another. In addition, many patients will self-medicate with over-the-counter analgesics, meaning that the cost to the NHS of recommending over-the-counter medicines such as paracetamol is only a fraction of the cost of recommending prescription-only medicines such as codeine (moreover, over-the-counter medicines tend to be less expensive to begin with).

Table 54 gives the direct cost of the 3 analgesics considered in the economic model for endometriosis (selected because of the availability of evidence on their cost and effectiveness). Table 55 gives indicative costs of all other analgesics specified in the protocol. The true economic cost of prescribing one over the other depends on factors not included in this table, including side effects, compliance and indirect costs.

The cost of ‘Generic’ analgesia is given as the cost of aspirin. Aspirin has a slightly higher cost than some other NSAIDs according to the electronic drug tariff; for example, Ibuprofen costs £0.86 for 24 400g tabs giving an annual cost of £40.05 and Naproxen costs £0.93 for 28 250g tabs giving an annual cost of £36.37. Nevertheless, it was thought appropriate to use the cost of aspirin as it is probably the most commonly prescribed NSAID, and the slightly higher cost is expected to offset indirect costs from drug prescription, such as side-effects, which are not included in Electronic Drug Tariff prices.

The economic model suggests that no analgesic is likely to be better than hormonal treatment; hormonal treatment is likely to be both more effective and cheaper than the best analgesics. These results are demonstrated in Table 56. The table shows that Tramadol likely dominates no treatment – being both cheaper and more effective – but that the next most effective set of analgesics are outside the range which would normally be considered for the NICE cost-effectiveness threshold of around £20,000

NSAIDs were excluded from most runs of the model; the evidence for their effectiveness was weak and contradictory (and the evidence upon which this was based was not clear in specifying which exact analgesic was used; NSAIDs were inferred from a description of the side effects). If the results for NSAIDs are accepted at face value, they would be more effective than hormonal treatment at a slightly higher cost, which would nonetheless be cost-effective at £20,000/quality adjusted life year (QALY) threshold. The Committee discussed how this could well be important evidence highlighting the effectiveness of NSAIDs versus other analgesics.

11.1.1.5. Clinical evidence statements

Very low quality evidence from 1 crossover RCT (n=20) showed that there was no difference in overall pain relief, unintended effects or need for supplementary analgesia when women with endometriosis received naproxen sodium compared to placebo for 2 menstrual cycles, although there was uncertainty around the estimate.

11.1.1.6. Evidence to recommendations

11.1.1.6.1. Relative value placed on the outcomes considered

The Committee prioritised pain relief, health-related quality or life and adverse events from analgesics (particularly those leading to withdrawal from treatment) as critical outcomes.

The Committee also discussed the need to take further supplementary analgesia, which was another outcome that was reported. No evidence was identified that reported on health-related quality of life.

11.1.1.6.2. Consideration of clinical benefits and harms

Pain is a common symptom of endometriosis and, when severe and/or persistent, can be completely debilitating, affecting one’s ability to perform routine daily activities, greatly limiting lifestyle and quality of life.

The Committee acknowledged that analgesia would only provide symptomatic relief of pain, rather than addressing any underlying pathology, but that effective pain relief can provide an alternative to more invasive treatment. The Committee noted that hormonal therapies used to treat endometriosis may take at least 1 menstrual cycle to become effective. For this reason, pain relief medication may be used until the long-term treatment begins to work.

The Committee noted that some women might tolerate significant harms associated with side effects of analgesics in order to have respite from their pain and that this trade off was variable depending on the severity of the woman’s symptoms and her individual circumstances.

11.1.1.6.3. Consideration of economic benefits and harms

The Committee acknowledged that hormonal treatment was likely to be more cost-effective than the best analgesics but reflected that this did not exclude giving an analgesic with another kind of treatment as, in general, analgesics were not thought to interact with other forms of treatment. The Committee also noted that analgesics might be considered cost-effective in the absence of other treatments. However, as there was no direct evidence on the effectiveness of analgesics in combination with other treatments for endometriosis the Committee made it clear that clinical judgement would be required if considering analgesics in combination with other treatments (e.g. hormonal or surgical treatments).

Although there are no results for the impact of analgesics on fertility (as this was not modelled), the Committee considered that the presence or absence of analgesics would be unlikely to alter a woman’s fertility and have a relatively smaller impact on fertility than other treatment options considered in this guideline. The Committee acknowledged some limited evidence that NSAIDs might inhibit ovulation if taken continuously during the cycle, (making conception less likely), but noted that if taken during the period, would not have an effect on ovulation. Members further pointed out that severe pain might reduce the likelihood of intercourse and hence analgesics might improve the chance of conception. Overall the Committee concluded that the impact of analgesics on fertility (especially NSAIDs) was not sufficiently researched to underpin a recommendation.

Estimating the resource impact of analgesics is difficult as many women will chose to self-medicate if prescribed over-the-counter analgesia (as this can often work out cheaper for both the woman and the NHS). The Committee described how the general principle of their recommendations – trialling cheap medication and considering more expensive analgesia if this failed – was current NHS practice, and so the recommendations are unlikely to represent a significant resource impact.

11.1.1.6.4. Quality of evidence

The available evidence was drawn from a single small trial conducted in 1985 and was of very low quality. A self-reported questionnaire to assess pain was used, although the validity of the pain scoring system was unclear. While the study indicated that 24 women were randomised, the results for only 20 women were reported for unintended effects of treatment and 19 for overall pain relief and for supplementary analgesia needed. There were other methodological flaws such as unclear allocation concealment and unclear reporting of exclusion criteria. The direction of the effect for overall pain relief, unintended effects and need for supplementary analgesia outcomes was in favour of naproxen sodium but, due to the small sample size, the study was underpowered and outcome effects had wide confidence intervals (CIs). No evidence was available for the other outcomes prioritised and no other relevant evidence assessing the effectiveness of any other type of analgesic for endometriosis-related pain was available.

The Committee considered that the small number of women included in the study and its short duration made it difficult to draw any valid conclusions. The Committee agreed that although there is no good evidence for use of analgesics in management of acute pain specific to endometriosis, there is robust evidence of effectiveness of analgesics for pain management in other areas and hence gave little weight to the limited evidence.

11.1.1.6.5. Other considerations

Due to the poor quality and limited evidence available, the Committee based their decisions on consensus and the experience and expertise of its members.

The Committee discussed the Pain Ladder developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for analgesia for cancer-related pain but which has since been adopted for acute and chronic non-malignant pain relief. This describes a 3-step progressive approach to use of pharmacologic agents proportional to the level of pain reported. The initial step uses oral administration of non-opioids such as paracetamol or NSAIDs. If pain is not controlled, then mild opioids such as codeine are tried and, as a last step, strong opioids such as morphine are used until the patient’s pain is alleviated. One benefit of the stepped approach is that adverse events can be discovered throughout the process.

The Committee discussed whether the addition of an opioid analgesic could be considered if pain was not adequately controlled after a trial period. However, the potential adverse effects of opioid analgesia, such as dependency, were recognised, given the chronic nature of endometriosis-related pain and, particularly, constipation. Therefore, the Committee concluded that a referral for diagnosis might be more appropriate and that there were other treatment options available.

The Committee also considered whether a research recommendation should be drafted for this topic. They agreed that research into analgesia in the management of pain related to endometriosis is not a priority for this guideline because there is sufficient indirect evidence from other conditions available to draw upon.

The Committee considered whether any different recommendations were necessary for adolescent women but concluded that none were required.

11.1.1.6.6. Key conclusions

The Committee concluded that a short trial of analgesics for first line management of pain in women with endometriosis-related pain is appropriate.

11.1.1.7. Recommendations

- 32.

For women with endometriosis-related pain, discuss the benefits and risks of analgesics, taking into account any comorbidities and the woman’s preferences.

- 33.

Consider a short trial (for example, 3 months) of paracetamol or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) alone or in combination for first-line management of endometriosis-related pain.

- 34.

If a trial of paracetamol or an NSAID (alone or in combination) does not provide adequate pain relief, consider other forms of pain management and referral for further assessment.

11.1.2. Neuromodulators (neuropathic pain treatment)

Review question: What is the effectiveness of neuromodulators for treating endometriosis, including recurrent and asymptomatic endometriosis?

11.1.2.1. Introduction

Neuromodulators, otherwise known as neuropathic analgesics, are used mainly by pain specialists and general practitioners (GPs) in the management of chronic, also known as, persistent pain. Neuromodulators differ from conventional analgesics such as NSAIDs in that they primarily affect the central nervous system’s modulation of pain, rather than peripheral meditators of inflammation. An overactive and hypersensitive nervous system contributes to the development and maintenance of chronic pain. Neuromodulators exert their effects via their modulation of this overactive and hypersensitive nervous system.

Many neuromodulators were originally developed with different aims, for example, as antidepressants or anticonvulsants. The main classes of neuromodulators are: the tricyclic antidepressants, for example, amitriptyline and nortriptyline; the selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors such as duloxetine; and the gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin). Under this heading we also considered capsaicin, ketamine, local anaesthetics (lidocaine) and nerve blocks. Certain opioid medications, such as tramadol and tapentadol, also have neuromodulating properties.

These medicines may also have important other effects, depending on their dose, on other related conditions that may be concurrently present, such as anxiety and/or depression. NICE already recommends a choice of amitriptyline, duloxetine, gabapentin or pregabalin as the initial treatment for neuropathic pain (CG 173).

Understanding the effectiveness of neuromodulators for women with endometriosis is important as, if useful, they might reduce the burden of pain and/or side effects from other medications, or offer an alternative to other types of treatment such as hormonal. If effective, they might reduce the need for surgery and prevent or reduce the chronicity of pain with its far-reaching consequences.

11.1.2.2. Description of clinical evidence

The objective of this review is to determine the clinical and cost effectiveness of neuromodulators to improve outcomes in women with endometriosis.

For full details, see review protocol in Appendix D.

We looked for systematic reviews, randomised and comparative observational studies assessing the effectiveness of neuromodulators in the management of endometriosis of any stage or severity. These may also include suspected diagnoses as described in detail in the protocol.

Two trials were identified that used local anaesthetics with a procedure called perturbation, which involves the insertion of a thin plastic catheter in the cervical canal. This catheter is then used to infuse the local anaesthetic through the uterine cavity and is then pertubated into the peritoneal cavity.

One trial was conducted in Sweden (Wickström 2013) with a number of associated published abstracts and 1 further full article are both associated with this particular trial (Edelstam 2012, Wickström 2012a, 2012b, 2012c). The local anaesthetic used in this trial was lidocaine. The second trial was conducted in Egypt, using the same procedure but with a different local anaesthetic bupivacaine (Shokeir 2015). In both trials the inclusion criteria included the requirement that endometriosis had been confirmed by laparoscopy.

Both trials reported pain as an outcome (as indicated on the visual analogue scale [VAS]). One of them also reported the rate of women who were overall satisfied with the procedure. The other trial also reported health-related quality of life as measured by the Endometriosis Health Profile-30 (EHP-30) as well as recurrence and need for other therapies. Fertility outcomes cannot be assessed because both studies excluded women who intended to become pregnant within the forthcoming year.

No further evidence was identified for any other type of neuromodulator or neuropathic analgesia.

Evidence for the outcomes from these trials is summarised in the clinical GRADE evidence profile below (Table 58). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix F study exclusion list in Appendix H, forest plots in Appendix I, full GRADE profiles in Appendix J and study evidence tables in Appendix G. Summary of included studies

A brief summary of the studies that were included in this review is presented in Table 57.

11.1.2.3. Clinical evidence profile

The clinical evidence profile for this review question is presented in Table 58.

Other reported findings – EHP-30 (endometriosis-related quality of life)

Quality of life scores were reported as medians with interquartile ranges and therefore could not be graphically presented as forest plots. They are presented in Table 59 below.

11.1.2.4. Economic evidence

No economic evidence was found on the use of neuromodulators in women with endometriosis.

As no evidence was found on the use of neuromodulators in women with endometriosis, the effectiveness of these treatments was calculated from. Consequently, not all treatments listed in the protocol could be included in the economic model.

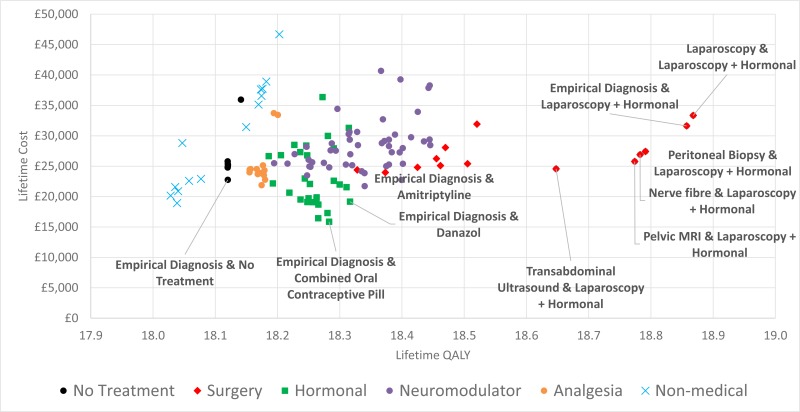

Table 61 demonstrates which neuromodulators might be selected as a cost-effective treatment on average. Both amitriptyline and gabapentin perform well relative to an incremental cost-utility ratio (ICER) of £20,000/QALY and are cheap enough that a diagnostic strategy of ‘empirical diagnosis’ – treating based on symptoms rather than a definitive diagnosis - can be pursued. However, this is only with reference to the class of neuromodulators; the main economic model indicates that neuromodulators are neither cheap enough to be considered in preference to hormonal treatment nor effective enough to be considered in preference to surgery. Given that there are some women who cannot tolerate hormonal therapy (usually because they are seeking a pregnancy, which is discussed below) these results might be important, as it is possible neuromodulators will be cost-effective in these women. This is relevant as, if a woman cannot have hormonal therapy but responds to neuromodulators, then it is unlikely surgery will be cost-effective for this woman.

It was thought that neuromodulators would not have a positive effect on women seeking to conceive and some neuromodulators would be harmful to a developing fetus. For these reasons, neuromodulators were not considered in an analysis of women where infertility was the main reason for their seeking treatment.

11.1.2.5. Clinical evidence statements

No evidence was identified that addressed the effectiveness of commonly used neuropathic analgesics.

11.1.2.5.1. Pertubation of lidocaine vs. placebo

Pain up to 12 months

Very low to low quality evidence from 1 randomised controlled trial (RCT) with 42 women with endometriosis suggested higher rates of women who reported a significant improvement in pain associated with pertubation of lidocaine compared to placebo at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. However the uncertainty around this improvement was too large to draw clear conclusions about its clinical effectiveness.

EHP-30

Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT with 42 women with endometriosis reported no clear differences between women treated with lidocaine compared to placebo at 6 and 12 months for the subscales pain, control and powerlessness, emotional well-being, self-image and sexual intercourse. A small difference on the social support subscale was reported at 6 but not 12 months (Table 59).

Recurrence at 12 months

Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=42) suggested a higher rate of recurrence in those receiving lidocaine compared to those in the placebo group. However, the uncertainty around this effect was too large to draw clear conclusions about this finding.

Escalating levels of pain with a need for other therapies at 12 months

Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=42) suggested that there were fewer women needing other treatments in the lidocaine group compared to the control group. However, there was too much uncertainty around this effect to draw clear conclusions from these findings

11.1.2.5.2. Pertubation of bipuvacaine vs. Placebo

Pain up to 3 months

Moderate to high quality evidence from 1 randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted with 60 women who have endometriosis reported improvements in pain at 1, 2 and 3 months associated with bipuvacaine pertubation. However, the uncertainty around this effect make it difficult to draw conclusions about the clinical significance of this finding.

Satisfaction with treatment at 3 months

High quality evidence from 1 RCT conducted with 60 women who have endometriosis showed a higher rate of satisfaction with bipuvacaine treatment compared to placebo.

11.1.2.6. Evidence to recommendations

11.1.2.6.1. Relative value placed on the outcomes considered

All reported outcomes (pain, endometriosis health profile, recurrence, satisfaction and need for further therapies) are critical for decision-making. However, the Committee did not place trust in the evidence for these outcomes since pertubation with local anaesthetic is not used in current practice.

11.1.2.6.2. Consideration of clinical benefits and harms

The Committee agreed that it was disappointing that there was no clinical evidence for the effectiveness of commonly used neuromodulators.

They recognised that there was much useful guidance in the NICE guidance Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings (Clinical Guideline 96). The Committee discussed how this guidance could be useful for professionals looking to manage pain in certain settings as it was unlikely to interact with surgical or hormonal treatments, which would be the main alternative pharmacological management strategies. Therefore a neuromodulator for pain management in addition to first line treatment might help reduce pain further. The Committee was made aware that because of the well-established value of neuromodulators in pain management the evidence for these treatments for endometriosis specifically was almost entirely lacking and consequently an expert consensus was reached that there was no feature of endometriosis that would specifically indicate that neuromodulators would behave systematically differently in endometriosis than other long-term conditions, and therefore that the findings of CG173 would be appropriate to rely on. The Committee discussed the risks of extrapolating the CG79 guidance which focuses on neuropathic pain. Endometriosis could be considered to have similar pathophysiological processes via central sensitisation to neuropathic pain conditions but the CG79 guidance which may mean that it may be questionable whether it is directly translatable.

Even though the trials indicated that there might be benefits of the pertubation method for the administration of local anaesthesia, the Committee considered the invasive nature of this. They agreed that this is a procedure that is not currently used in the NHS and that the evidence is not convincing to warrant a change in practice. The Committee raised concerns that the discomfort and possible side effects from the intervention would outweigh the possible benefits.

The Committee was of the opinion that the nature of this treatment make it unlikely to be adopted because it would require repeated monthly administrations (to co-occur with the menstrual cycle).

11.1.2.6.3. Consideration of economic benefits and harms

Based on NICE guidance CG173, both amitriptyline and gabapentin perform well relative to an ICER of £20,000/QALY and are inexpensive enough that a diagnostic strategy of ‘empirical diagnosis’ – treating all those with symptoms of endometriosis without a confirmatory diagnostic test - can be pursued. However, this is only with reference to the class of neuromodulators. The Committee discussed comparative economic considerations indicating that neuromodulators are neither inexpensive enough to be considered in preference to hormonal treatment nor effective enough to be considered in preference to surgery. There are also some women who cannot tolerate or do not want to take hormonal therapy (usually because they are seeking to conceive, at which time neuromodulators would not be the appropriate option). In other cases where a woman cannot have hormonal therapy, does not consider pregnancy but responds to neuromodulators, then it is unlikely surgery will be cost-effective for this woman.

In the very specific case of a woman who cannot have hormonal therapy, is not considering pregnancy and yet responds to neuromodulators, then the economic model indicates that neuromodulators should be trialled as a first line treatment (before considering surgery). It is difficult to imagine the personal circumstances of such a woman, and so it may be that in most cases where neuromodulators are recommended by the economic model as a first line treatment that the economic model does not accurately capture these specific circumstances.

As the Committee is only recommending neuromodulators in line with the NICE Guideline on the topic, there will be no significant resource impact.

11.1.2.6.4. Quality of evidence

The evidence was of very low to moderate quality, according to GRADE criteria. Even though the methodology of the trials was well described, there were inconsistencies in the results reported (for instance, differences in results when pain was reported as a categorical or continuous measure). There were also a number of outcomes that were only reported as medians, for which it is difficult to estimate the confidence in the effect size.

The Committee therefore had little confidence in the findings of the trials.

11.1.2.6.5. Other considerations

The Committee noted that there is a substantial amount of evidence for nerve ablation, specifically in the form of Laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation (LUNA). However LUNA has been covered by a NICE Interventional Procedure Guideline (IPG234) and so was outside the scope of this Guideline. The IPG concluded that the evidence on laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation for chronic pelvic pain suggests that it is not efficacious and therefore should not be used.

11.1.2.6.6. Key conclusions

The Committee concluded that there was currently insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of neuromodulators in managing pain of women with endometriosis. Little confidence was placed in the evidence for a method of administering local anaesthetics, which is not currently used in the NHS and hence the Committee decided not to make any recommendation regarding this technique. They agreed that the recommendations set out in NICE guidance CG173 would be generalizable to women with endometriosis and therefore cross-referenced to this guidance.

11.1.2.7. Recommendations

- 35.

For recommendations on using neuromodulators to treat neuropathic pain, see the NICE guideline on neuropathic pain.

11.1.3. Hormonal medical treatments

Review question: What is the effectiveness of hormonal medical treatments for treating endometriosis compared to placebo, other hormonal medical treatments, usual care, surgery, or surgery in combination with hormonal treatment?

11.1.3.1. Introduction

Endometriosis is considered a predominantly oestrogen-dependent condition. Thus, ovarian suppression with hormones is currently offered as an alternative to surgical excision to treat the disease and its symptoms. However, clinical practice with regards to hormonal treatment varies widely, because of the implications of each option. None of the hormones used to manage endometriosis (or, in fact, any drug) are free of side effects, but the severity and tolerability of the side effects can vary quite significantly. Many of the hormones used to manage endometriosis-associated pain will also reduce menstrual bleeding and this may be advantageous. Similarly, the contraceptive properties of the hormones may be welcome if the woman does not wish to become pregnant at this moment in time, or unwanted if fertility is an issue. All these factors should be taken into consideration when prescribing hormones to women for the treatment of endometriosis. The effects of hormonal contraceptives, progestogens, anti-progestogens, gonadotrophin releasing hormone agonists (GnRH agonists) and aromatase inhibitors on endometriosis symptoms are discussed below.

The principal aim of this review is to determine the clinical and cost effectiveness of hormonal medical treatments in reducing pain in women with endometriosis.

For full details, see the review protocols in Appendix D.

11.1.3.2. Network Meta-analysis

11.1.3.2.1. Methods

The results of conventional pairwise comparison (and meta-analyses) of direct evidence alone do not help to fully inform which intervention is most effective in the treatment of endometriosis. The challenge of interpretation arises for 2 main reasons:

- In isolation, each pairwise comparison does not fully inform the choice between the different treatments and having a series of discrete pairwise comparisons can be disjointed and difficult to interpret.

- RCT evidence is not available that directly compares treatments of clinical interest are not fully available, for example, comparison between certain types of hormonal therapy. This makes choice difficult unless based on patient preference or cost.

To overcome these issues, a hierarchical Bayesian network meta-analysis (NMA) was performed in addition to a pairwise comparison of hormonal treatments. Advantages of performing this type of analysis are:

- It allows the synthesis of data from direct and indirect comparisons without breaking randomisation, to produce measures of treatment effect and ranking of different interventions. If treatment A has never been compared against treatment B head to head, but these 2 interventions have been compared to a common comparator directly, then an indirect treatment comparison can use the relative effects of the 2 treatments versus the common comparator. Indirect estimates can be calculated whenever there is a path linking 2 treatments through a set of common comparators. All the randomised evidence is considered simultaneously within the same model.

- For every intervention in a connected network, a relative effect estimate (with its 95% credible intervals) can be estimated versus any other intervention. These estimates provide a useful clinical summary of the results and facilitate the formation of recommendations based on all of the best available evidence, while appropriately accounting for uncertainty.

- Estimates from the NMA can be used to directly parameterise treatment effectiveness in cost-effectiveness modelling of multiple treatments.

The terms indirect treatment comparisons, mixed treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis are used interchangeably, though we use the term NMA throughout the guideline.

Study selection and data collection

For full details, see review and analysis protocols in Appendices K and L.

11.1.3.2.2. Outcome measures for NMA

For assessing the effectiveness of treatments, the Committee identified pain relief, health-related quality of life (QoL) and adverse events as critical outcomes for which NMA could be used to aid decision-making. NMAs were performed on these outcomes where evidence was available.

Pain relief

For pain relief, the visual analogue scale (VAS) was considered by the Committee to be the most widely used useful pain scale for which data would be available. A series of subscales first reported by Biberoglu and Behrman (1981) were also frequently used in studies of hormonal treatments and NMAs of these subscales were also performed to provide additional information on pain relief. There was sufficient evidence available for NMA for dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia and non-menstrual pelvic pain subscales, though not for induration and pelvic tenderness subscales. Therefore induration and pelvic tenderness were analysed within a separate pairwise comparison analysis. Dysmenorrhoea and nonmenstrual pelvic pain were used in a multivariate analysis to inform the VAS scale, so their results are not presented separately here.

Health-related QoL

For health-related QoL, the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) was determined by the Committee to the most useful scale that was widely used in the literature. However, there were not a sufficient number of studies available from the systematic review to allow for NMA. Therefore these studies were analysed within the separate pairwise comparison analysis where appropriate.

Adverse events

As adverse events varied substantially depending on the treatment in question, the Committee felt that the number of women discontinuing treatments due to adverse events was a more generalizable and useful outcome, as this also accounted for how severe women felt an adverse event to be (i.e. it had to be sufficiently severe for them to discontinue treatment).

11.1.3.2.3. Statistical methodology

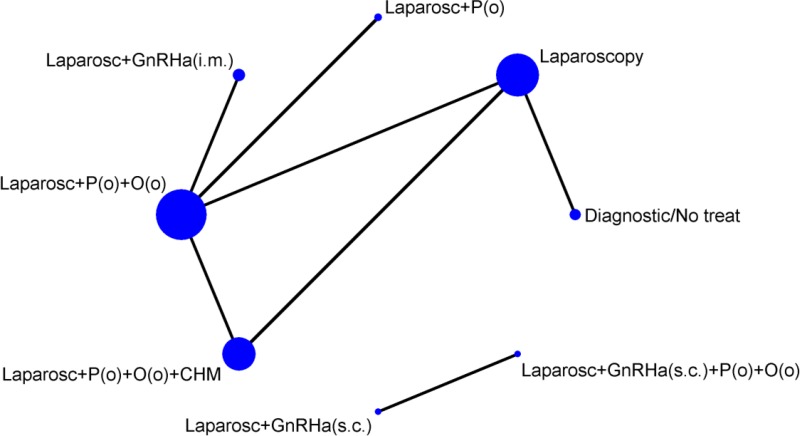

Due to difficulty in obtaining stable estimates from the model, NMAs were conducted separately for hormonal and non-pharmacological therapies, and for surgery and surgery plus hormonal treatment. The Committee felt that the difficulties in model estimation were likely to be because the populations may not have been sufficiently homogeneous, as patients receiving surgical treatment were likely to have failed on hormonal treatments, thus violating the assumption of transitivity.

Data were available for a number of treatments and routes of administration. Due to the sparseness of the networks, it was necessary to group treatments within different classes and assume a common class effect (Table 62). The common class effects were assessed to identify if it was reasonable to assume similarity of treatment effects within classes. Though data were often too limited to be able to closely examine within-class variation there was no evidence to suggest that treatment effects differed substantially within classes. Multi-level NMA models with treatments nested within classes were also examined, though this added complexity did not improve model fit for any of the analyses. Therefore common class effects were assumed throughout the analyses.

There are 3 key assumptions behind an NMA: similarity, transitivity and consistency.

Similarity across trials is the critical rationale for the consistency assumption to be valid as, by ensuring the clinical characteristics of the trials are similar, we ensure consistency in the data analysis.

More specifically, randomisation holds only within individual trials, not across the trials. Therefore, if the trials differ in terms of patient characteristics, measurement and/or definition of outcome, length of follow-up across the direct comparisons, the similarity assumption is violated and this can bias the analysis. Potential sources of heterogeneity arising from trials of interventions for endometriosis and attempts made to identify and account for heterogeneity are:

- Different population: for example, mixed populations of women with and without endometrioma.

- Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the validity of the assumption of similarity of effect for treatments for women with and without endometrioma.

- Different duration of treatment or study follow-up:

- Although data were limited to reliably assess the effect of study duration, relative treatment effects appeared to be similar across studies of different duration that fitted the inclusion criteria specified in the analysis protocol.

- Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of removing studies of short duration.

- Different dosages of pharmacological treatments:

- These typically showed little variation and were within the dose ranges specified by the British National Formulary (BNF).

Transitivity is the assumption that an intervention (A) will have the same efficacy in a study comparing A vs. B as it will in a study comparing A vs. C. Another way of looking at it, in terms of the study participants, is that we assume that it is equally likely that any patient in the network could have been given any of the treatments in the network and would have responded to the treatments in the same way (depending on how efficacious the treatments are).

This assumption is closely related to similarity in that if participants in a study comparing A vs. B are not the same as those in a study comparing A vs. C. For example, if those in a comparison of A vs. B were women seeking treatment to improve fertility and those in A vs. C were women whose primary concern was pain relief, then both the similarity and transitivity assumptions would be violated, hence the importance in our analysis of keeping these populations distinct.

The final assumption is consistency/coherence of the network. It is important that for a network that contains closed loops of treatments (e.g. with studies comparing A vs. B, B vs. C and A vs. C), the indirect comparisons are consistent with the direct comparisons. Discrepancies between direct and indirect estimates of effect may result from several possible causes. One possible cause is ‘chance’ and if this is the case then the NMA results are likely to be more precise as they pool together more data than conventional meta-analysis estimates alone. However, a second possible cause could be due to differences between the trials included in terms of their clinical or methodological characteristics, which would therefore raise concerns about the validity of the network.

There were no studies that fitted the NMA inclusion criteria for the following treatments in Table 62: anti-androgens, selective oestrogen receptor modulators, tibolone, nutritional supplements, Chinese herbal medicine, and dietary interventions. As no studies investigating non-pharmacological treatments fitted the inclusion criteria for the NMA, the analyses presented are only of hormonal treatments.

11.1.3.2.4. Summary of included studies

Studies included in the NMA

All studies included women with laparoscopic confirmation of endometriosis.

11.1.3.2.5. Studies excluded from the NMA

Table 64 lists the studies that were excluded from the NMA for statistical reasons.

11.1.3.2.6. Clinical evidence profile

Pain relief – VAS

Due to difficulty in achieving convergence during estimation, NMAs were conducted separately for hormonal and non-pharmacological therapies, and for surgery and surgery plus hormonal treatment. The Committee felt that this was likely to be because the populations may not have been sufficiently homogeneous, as patients receiving surgical treatment were likely to have failed on hormonal treatments, thus violating the assumption of transitivity.

Hormonal treatments

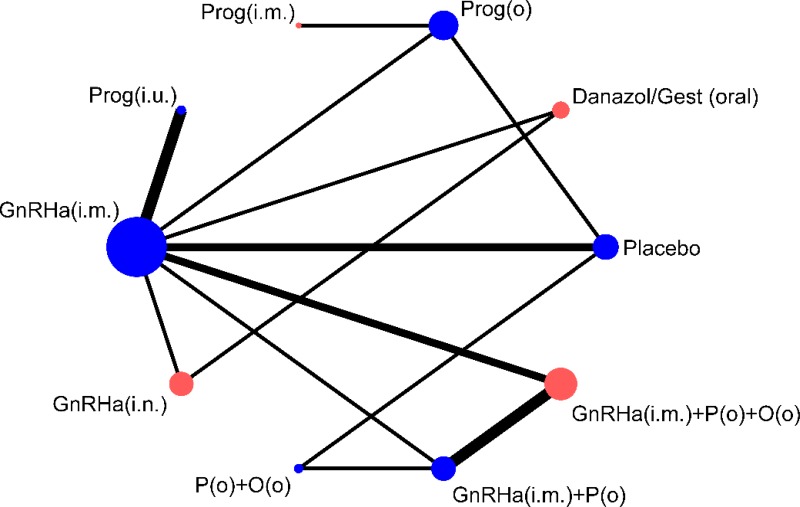

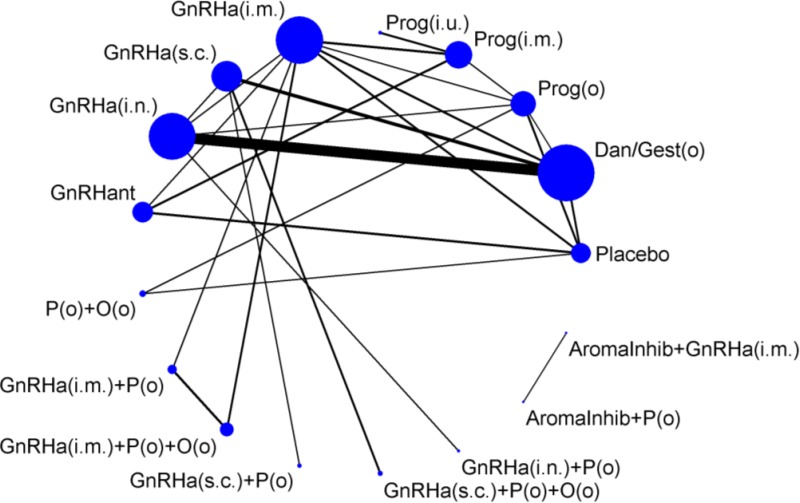

Fifteen trials of 10 hormonal treatment classes were included in the network for the outcome of pain relief on the VAS, with a total sample size of 1,680 women (Figure 13). No studies reported data on non-pharmacological treatment that could be used in the network. One study was at high risk of bias, 7 were at moderate risk of bias and 7 at low risk of bias.

Table 65 presents the results of the pairwise meta-analyses of the VAS where they were available (direct comparisons; upper right section of table) together with the results from the multivariate NMA for every possible class comparison (lower left section of table), presented as mean differences. A multivariate NMA was performed as this allowed for the incorporation of additional information from dysmenorrhoea and non-menstrual pelvic pain Biberoglu and Behrman subscales, allowing estimation of the efficacy of treatments not investigated using the VAS (progestogens (i.m.), danazol/gestrinone, GnRHa (i.n.) and GnRHa (i.m.) plus the pill). The VAS is a 0–100 patient-reported scale, on which a difference of 10 points has been shown to be clinically significant to patients (Gerlinger 2012).

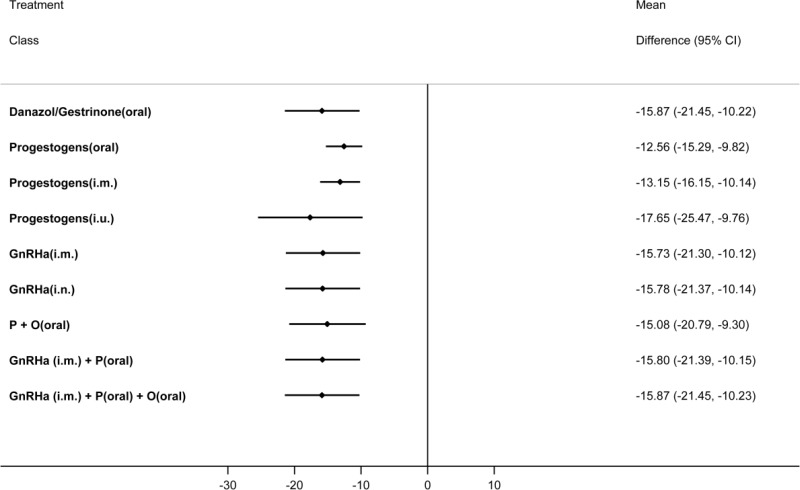

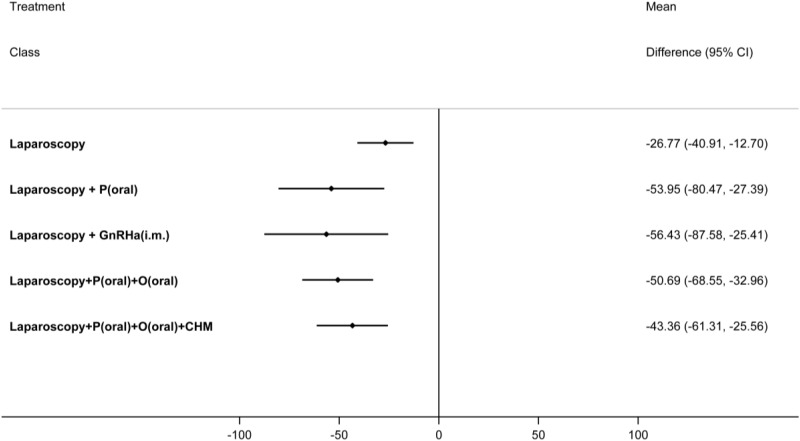

NMA results were derived from a fixed effects multivariate model. Figure 14 graphically presents the results computed by the NMA for each treatment versus placebo.

All treatments led to a clinically significant reduction in pain on the VAS when compared to placebo. The magnitude of this treatment effect was similar for all treatments, suggesting that there was little difference between them in their capacity to reduce pain. No other significant differences were found between the hormonal treatments.

The levornorgestrel implant (progestogens (i.u.)) had the highest probability of being among the best 3 treatments (74.2%), followed by danazol/gestrinone (52.6%) and GnRHa (i.m.) plus the pill (52.5%). The results of this are described in Table 66.

Results were broadly similar from the multivariate and univariate NMA where information was available for comparison. The largest differences were for the progestogens (i.u.) (considerably more effective in the multivariate than in the univariate NMA) and GnRHa (i.m) (less effective in the multivariate than in the univariate NMA) (Appendix L).

Sufficient data to calculate standard errors (SEs) was not available in 4 of the 15 trials. However, sensitivity analyses using the upper 95% CrI of the posterior for the imputed SEs showed that estimates and their 95% CrIs were very insensitive to the imputed SEs (Appendix L).

The multivariate nature of the network did not allow for simple assessment of incoherence, though it was assessed for each of the univariate outcomes and was not found to be present in any closed loops. However there were some differences between the direct estimates on the VAS scale and those from the NMA, particularly for progestogens (oral) versus GnRHa (i.m.). These differences are due to the multivariate analysis and the inclusion of evidence from the Biberoglu and Behrman scales and therefore reflect incoherence between the outcomes rather than between the treatment comparisons. Although this appears to change the direction of effect in some comparisons, the change is very small and not clinically meaningful.

Pain relief – dyspareunia (Biberoglu and Behrman)

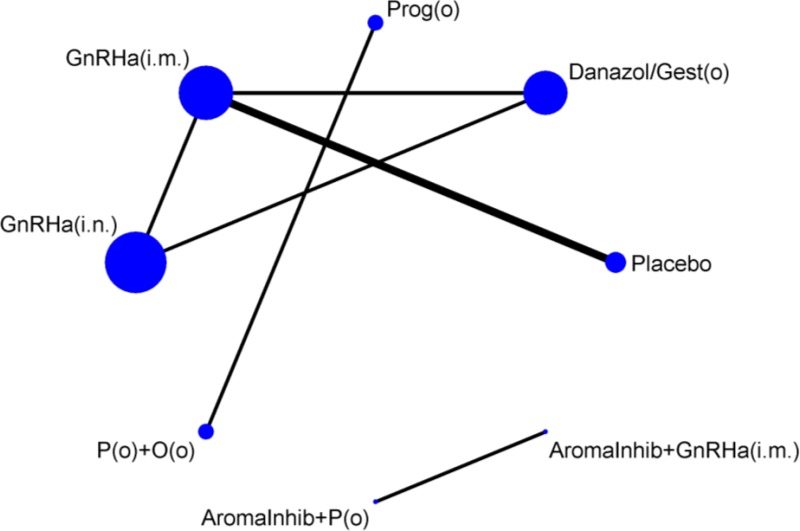

Five trials of 4 treatment classes were included in the network for the outcome of dyspareunia, with a total sample size of 572 women (Figure 15). One study was at high risk of bias, 2 were at moderate risk of bias and 2 were at low risk of bias.

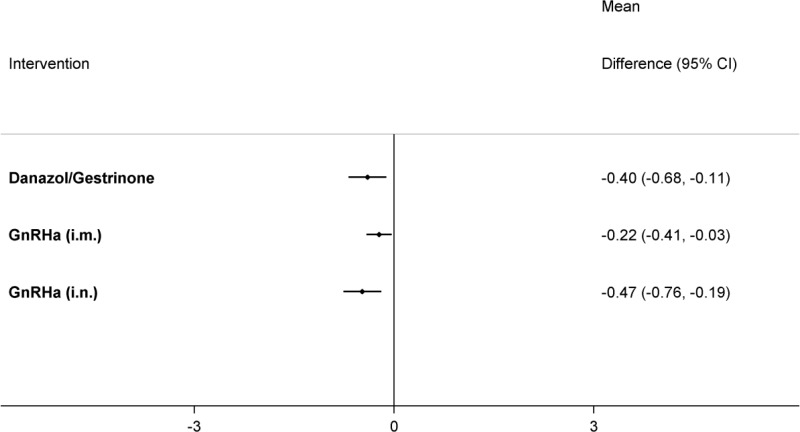

Table 67 presents the results of the conventional pairwise meta-analyses (direct comparisons; upper right section of table) together with the results from the NMA for every possible class comparison (lower left section of table), presented as mean differences. Dyspareunia was assessed using a 0–3 patient-reported scale developed by Biberoglu and Behrman (1981). NMA results were derived from a fixed effects model.

All treatments were significantly better at relieving dyspareunia than placebo/no treatment, although the improvement was quite small. GnRHa (i.n.) was also found to be significantly better at relieving dyspareunia than GnRHa (i.m.), which led to it having the highest probability of being the best treatment (85.1%), followed by danazol/gestrinone (14.3%) (see Table 68). Results from this NMA should be interpreted with caution, as sufficient data to calculate SEs was only available in 2 of the 5 trials. Sensitivity analyses using the upper 95% CrI of the posterior for the imputed SEs showed that the probability of being the best treatment results were sensitive to the imputed SEs. With larger SEs, there was more uncertainty regarding whether GnRHa (i.n.) or danazol/gestrinone were the better treatment (Appendix L).

There was no clear evidence of incoherence in the closed loop of GnRHa (i.m.), danazol/gestrinone and GnRHa (i.n.). However, there was very limited statistical power to test for this and, as the direction of effect differs between 2 of the direct and indirect estimates, results of this network should be treated with caution.

- GnRHa (i.m.) vs. danazol/gestrinone (p=0.123)

- direct MD=0.33 (95% CrI: 0.04 to 0.65)

- indirect MD=−0.01 (95% CrI: −0.33 to 0.31)

- GnRHa (i.n.) vs. danazol/gestrinone (p=0.115)

- direct MD=−0.12 (95% CrI: −0.27 to 0.03)

- indirect MD=0.22 (95% CrI: −0.17 to 0.62)

- GnRHa (i.n.) vs. GnRHa (i.m.) (p=0.115)

- direct MD=−0.11 (95% CrI: −0.38 to 0.17)

- indirect MD=−0.45 (95% CrI: −0.77 to −0.13)

Discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events

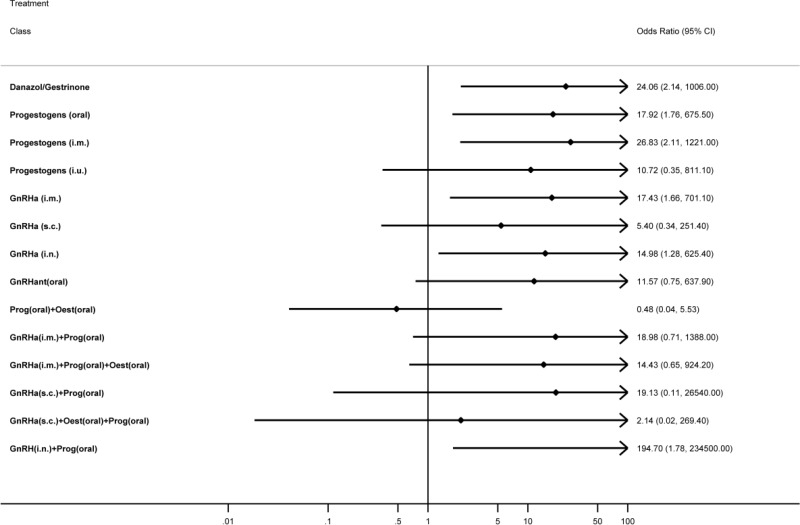

36 trials of 15 treatment classes were included in the network for the outcome of discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events, with a total sample size of 5,319 women (Figure 17). No studies that reported data on non-pharmacological treatments could be included in the network. Five studies were at high risk of bias, 21 studies were at moderate risk of bias and 10 studies were at low risk of bias.

Table 69 presents the results of the pairwise meta-analyses (direct comparisons; upper right section of table) together with the results from the NMA for every possible class comparison (lower left section of table), presented as odds ratios (ORs). These results were derived from a random effects model with very high heterogeneity (between-study SD: 0.94 (95% CrI: 0.45 to 1.69)). Accounting for severity of endometriosis (as measured by the rAFS) did not further explain the high heterogeneity.

Several treatment classes were found to result in significantly more discontinuations of treatment due to adverse events than placebo/no treatment (danazol/gestrinone, progestogens (oral), progestogens (i.m.), GnRHa (i.m.), GnRHa (i.n.) and GnRHa (i.n.) plus progestogen). The combined oral contraceptive pill (progestogen plus oestrogen (oral)), was found to lead to significantly less discontinuation than danazol/gestrinone, progestogen alone (oral), progestogen (i.m.), GnRHa (i.m.) and GnRHa (i.n.) plus progestogen. Figure 18 graphically presents the results computed by the NMA for each treatment versus placebo.

Though this outcome was taken where reported in studies as discontinuation due to adverse events, there may be some degree of reporting bias for this outcome - it is likely that women who are not finding the treatment effective or women who have difficulty with treatment compliance, may also be likely to discontinue treatment. For these women, even though they may cite adverse events as their reason for discontinuing treatment, treatment efficacy may play a part. Therefore this outcome is not independent of treatment efficacy. So because the combined oral contraceptive pill (progestogen plus oestrogen (oral)) was found to be effective, this may in part explain why it had the highest probability of being 1 of the best 3 treatments for discontinuation due to adverse events (87.8%). Placebo/no treatment had the next highest probability (82.13%) (Table 70).

The treatments with the highest probability of being 1 of the 3 worst for discontinuation were GnRHa (i.n.) plus progestogen (oral) (78.8%), progestogen (i.m.) (39.1%), GnRHa (s.c.) plus progestogen (38.8%).

There was strong evidence of serious incoherence in the closed loop of GnRHa (s.c.), danazol/gestrinone and GnRHa (i.n.). As the direction of effect differs between direct and indirect estimates, results of this network should be treated with caution. No significant incoherence was found in any other closed loops of treatments (Appendix L).

- GnRHa (s.c.) vs. danazol/gestrinone (p=0.005)

- direct OR = 0.10 (95% CrI: 0.03 to 0.25)

- indirect OR = 2.25 (95% CrI: 0.41 to 12.18)

- GnRHa (i.n.) vs. danazol/gestrinone (p=0.025)

- direct OR = 1.09 (95% CrI: 0.45 to 2.34)

- indirect OR = 0.15 (95% CrI: 0.05 to 0.59)

- GnRHa (i.n.) vs. GnRHa (s.c.) (p=0.04)

- direct OR = 0.42 (95% CrI: 0.09 to 1.88)

- indirect OR = 9.03 (95% CrI: 3.00 to 33.12).

11.1.3.3. Pairwise comparison

11.1.3.3.1. Description of clinical evidence

This pairwise comparison analysis accompanies the NMA that examined pain (VAS total scores and Biblioglu and Behrman criteria and) and withdrawal due to adverse events. The potential evidence for this analysis included RCTs identified from the searches performed on the basis of the protocol (see Appendix D) as well as RCTs that were considered for the NMA.

In total, 7 studies were included in this review. Three were Cochrane systematic reviews (Brown 2010, 2012 and Davis 2007) and 4 were RCTs (Harada 2008, Ling 1999, Parazzini 2000 and Schlaff 2006). 10 RCTs from the Brown 2010 (Agarwal 1997, Bergqvist 1998, Burry 1992, Cheng 2005, Fedele 1989, Fedele 1993, Fraser 1991, NEET 1992, Petta 2005, Wheeler 1992), 2 RCTs from the Brown 2012 (Bergqvist 2001, Vercellini 1996) and 1 RCT from the Davis 2007 (Vercellini 1993) Cochrane systematic reviews were relevant.

The population of interest was women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis of any stage or severity who did not receive surgery in conjunction with the hormonal medical treatments, although who may have had surgery prior to trial recruitment. Evidence was available for comparisons of hormonal treatments with placebo or no treatment (4 RCTs), for head to head hormonal treatment comparisons with placebo (6 RCTs) or without placebo (5 RCT) use in each treatment arm and for hormonal treatment combinations compared with a single hormonal treatment (2 RCTs).

The Committee specified critical outcomes of pain (for outcomes not included in the NMA), quality of life and unintended effects from treatment. However, many reports of unintended effects were identified (type, incidence and duration of side effects), preventing their meaningful inclusion in the pairwise analysis. Therefore these were addressed as ‘withdrawal from hormonal treatment due to adverse events’ in the NMA.

Hormonal treatments compared with placebo

Evidence was available from 3 studies that compared hormonal treatments with placebo or no treatment. One was a Cochrane systematic review (Brown 2010) and 2 were RCTs (Harada 2008 and Ling 1999). Two RCTs within the Cochrane systematic review were relevant (Bergqvist 1998, Fedele 1993).

All participants had a diagnosis or symptoms of endometriosis. One RCT examined a comparison of a GnRH agonist (buserelin intranasal (IN)) to expectant management in a population of women whose main symptom was infertility and who had undergone diagnostic laparoscopy combined with dilation and curettage (D&C) (Fedele 1993).

Two RCTs examined comparisons of GnRH agonists to placebo (triptorelin IM (intramuscular) depot and leuprolide IM depot) (Bergqvist 1998 and Ling 1999, respectively). One RCT compared a combined oral contraceptive pill to placebo (Harada 2008).

Evidence was only available for the critical outcome of pain (outcomes not included in the NMAs). There was no evidence available for any other critical or important outcomes.

Hormonal treatment compared with another hormonal treatment

Evidence was available from 2 studies comparing a hormonal treatment to another hormonal treatment. One was a Cochrane systematic review (Brown 2010) and one was a RCT (Schlaff 2006). Four RCTs within the Cochrane systematic review were relevant (Burry 1992, Cheng 2005, Fedele 1989, Petta 2005).

Three RCTs examined a comparison of a GnRH agonist (nafarelin IN or buserelin IN) to danazol (Burry 1992, Cheng 2005, Fedele 1989). One RCT compared leuprolide IM to a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) to (Petta 2010) and 1 RCT compared leuprolide to depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) subcutaneous (SC) injections (Schlaff 2006). All participants had laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis. One trial (Fedele 1989) included infertile women only.

Evidence was available for the critical outcomes of pain (outcomes not included in the NMA) and quality of life, and for the important outcomes of patients requiring surgery because of reappearance of symptoms and the effect on daily activities. There was no evidence available for any other important outcomes.

Hormonal treatment with placebo compared with another hormonal treatment with placebo

Evidence was available from 2 Cochrane systematic reviews (Brown 2010; Brown 2012) comparing a GnRH agonist to another hormonal treatment with use of placebos in each trial arm to blind for route of administration. Five RCTs were relevant in total: 4 RCTs from the Brown 2010 Cochrane systematic review (Agarwal 1997, Fraser 1991, NEET 1992, Wheeler 1992); and 1 RCT from the Brown 2012 Cochrane systematic review (Bergqvist 2001).

Four trials examined intranasal nafarelin (Agarwal 1997, Bergqvist 2001, Fraser 1991, NEET 1992) and 1 trial examined the use of depot leuprolide (Wheeler 1992).

One RCT examined a comparison of nafarelin IN and placebo IM injections to leuprolide acetate depot intramuscular (IM) injections and placebo IN (Agarwal 1997). One RCT compared nafarelin IN plus placebo tablets twice daily to MPA tablets and placebo IN (Bergqvist 2001).

Three trials compared the use of a GnRH agonist to danazol (Fraser 1991, NEET 1992, Wheeler 1992). Two trials compared the use of nafarelin IN to danazol with placebo in both treatment arms (Fraser 1991, NEET 1992). The first RCT compared of nafarelin IN and oral placebo to oral danazol and placebo IN over 6 months (Fraser 1991). The second RCT compared nafarelin IN and oral placebo capsules to oral danazol capsules and IN placebo (NEET 1992).

The final RCT compared a form of leuprolide depot injections and oral placebo to danazol and placebo IM injections (Wheeler 1992).

Evidence was available for the critical outcomes of pain relief (those outcomes not included in the NMA) and quality of life and for the important outcome of effects on daily activities. There was no evidence available for any important outcomes.

Hormonal treatment compared with combined oral contraceptive pill

Three studies comparing hormonal treatment to combined oral contraceptive pill (cOCP) were included in this review. Evidence was available from 2 Cochrane systematic reviews (Davis 2007, Brown 2012) and 1 RCT (Parazzini 2000). One RCT within each Cochrane systematic review was relevant (Vercellini 1993 and 1996, respectively).

All participants had laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis. One RCT examined a comparison of a GnRH agonist (triptorelin slow release for 4 months) followed by treatment with gestodene and ethinylestradiol (E/P pill) to E/P pill alone (Parazzini 2000). One RCT compared a GnRH agonist (goserelin subcutaneous depot) to cOCP (ethinylestradiol and desogestrel) (Vercellini 1993) and 1 RCT compared depot medroxyprogesterone acetate to cOCP (ethinylestradiol and desogestrel) plus danazol (Vercellini 2012). In 1 study (Parazzini 2000) additional treatment for relief of pain with naproxen sodium as first-line treatment was allowed.

Evidence was available for the critical outcome of pain (outcomes not included in the NMA) and for an important outcome of patient satisfaction. There was no evidence available for any other critical or important outcomes.

Studies are summarised in the tables below Table 71 and the available evidence is presented by comparison in the clinical GRADE evidence profiles below (Table 72 to Table 85). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix F, study exclusion list in Appendix H, forest plots in Appendix I, full GRADE profiles in Appendix J and study evidence tables in Appendix G. Summary of included studies

A summary of the studies that were included in this review are presented in Table 71.

11.1.3.3.2. Clinical evidence profile

The clinical evidence profiles for this review question are presented in Table 72 to Table 85.

11.1.3.3.3. Economic evidence

Cost effectiveness papers

Three studies were identified concerned with the cost-effectiveness of hormonal therapy in the treatment of endometriosis.

Lukac (2011a)

This paper refers to an analysis of the Slovakian AU19 trial on endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. It compares dienogest with Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormone agonists (GnRHa) over a period of 2 years. The source for costing data are “published price lists, clinical guidelines, product labels and expert opinion” and the source for QALY data is the SF-36 QoL instrument. The paper describes a Markov Chain model with a discount rate of 5% although it reports some data on the direct costs of these treatments with and without diagnostic laparoscopy.

The paper finds dienogest saves €506 and gains 0.002 QALYs relative to GnRHas. This indicates dienogest dominates GnRHa and would be considered cost-effective in any system. The authors include a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) implying that dienogest is cost-effective at a threshold of €18,000 / QALY (the Slovakian threshold, equivalent to around £15,000 / QALY) in 69% of cases

Lukac (2011b)

This paper appears to be a re-analysis of Lukac (2011a) as it refers to the same AU19 trial and finds similar results. The difference appears to be that this paper looks at a 5-year time horizon whereas the first paper looks at a 2-year time horizon. This paper finds a cost saving of €426 and a QALY gain of 0.069 QALYs, again indicating dienogest dominates GnRHas.

Bodner, Vale, Ratcliffe & Farrar (1996)

This paper refers to a subpopulation of 60 women with infertility taken from a full cohort of 273 enrolled in the Gynaecology Audit Project in Scotland (GAPS). It was intended principally to demonstrate a methodological point around using medical audit data to underpin economic evaluation, but was still considered relevant to include in this review as part of the audit data considered were costs and health outcomes. 35 women were treated with ‘expectant management’, 21 treated medically and 2 treated surgically (the remaining 2 women were on a surgical waiting list – it is not clear why these women were not included in the expectant management group).

The main outcome measure considered was fertility rates, but participants also completed an SF-36 QoL questionnaire. The source of cost data was NHS Reference Costs and estimates obtained by interviews with clinical managers. The time horizon was 6 months and the discount rate 6%.

The cost per patient alternative were £387.29 for expectant management, £645.02 for medical management and £1594.06 for surgical management. The SF-36 general health scores (and SDs) were an improvement of 61.0 (21.1) to 61.4 (29.9) in the medical group and a deterioration of 76.4 (18.2) to 75.3 (22.0) in the expectant management group. There were not enough women in the surgical group to report accurate scores. Neither of these changes would be considered statistically significant by any reasonable criteria, but – if they were significant – would represent an ICER of £17,200 indicating medical management is likely to be cost-effective compared to no treatment at the standard threshold of £20,000 / QALY – although it should be cautioned that the short follow up means that the effect of the (contraceptive) hormonal medical management on long-term QALYs may not have been properly accounted for.

Only 2 of the 60 women became pregnant by the end of the study, which is consistent with a view where endometriosis is highly damaging to fertility but does not give much analysable information about the cost-effectiveness of strategies to treat endometriosis-related infertility.

Cost only papers

Additionally, 5 studies were identified looking only at the costs of hormonal therapy. Since none of these papers were based on a UK perspective it was thought that conventional NHS costing sources were likely to be more relevant and so the Committee did not weight their evidence strongly in making a final recommendation, but Table 86 gives a high-level summary of the relevant information.

11.1.3.3.4. Economic model output

The cost of hormonal treatments can vary greatly depending on the dose required to achieve amenorrhea, the route of administration and any issues relating to unwanted side effects (perhaps the most important of which is infertility). Nevertheless it is known that there are a cluster of extremely cheap hormonal treatments (including the combined oral contraceptive pill) and a cluster of extremely high-cost treatments including dienogest and GnRHas.

Owing to a lack of evidence on a number of these treatments, only 4 were included for analysis in the final model as other treatments were not suitable for inclusion in the NMA.

Note that there is a significant issue with the costing of the 2 more routine contraceptives, which is that some women take these contraceptives purely to prevent pregnancy. This means that the opportunity cost of the NHS prescribing these drugs to these women is zero, which is a consideration the Committee made when discussing whether there was a case to recommend the more expensive hormonal treatments.

Hormonal treatments are both highly cost-effective on average and highly likely to be cost-effective vs. no treatment for any individual patient. This effect explains why Empirical Diagnosis & Danazol can have such a high ICER (£98,467) but also such a high probability of being cost-effective relative to no treatment. Another important point is how little difference there is between the combined oral contraceptive pill and Progestogen treatment – Progestogen treatment is fractionally cheaper based on the economic evidence and fractionally less effective based on the NMA, but patient-level analysis suggests that at £20,000 / QALY around 45% - 50% of patients offered the one treatment would actually have done better if offered the other. This indicates that the type of contraceptive might not be as important as the model implies as there is so little difference between them. This does not apply to GnRHas and Danazol, which are notably more expensive and only cost-effective at cost/QALY thresholds around one hundred thousand pounds (GnRHas are dominated by Danazol in this model, but if Danazol is removed the ICER for the most cost-effective GnRHa is £173,760).

The Committee discussed how this was entirely expected; hormonal treatments are known to be effective for endometriosis and known to be cheap and safe to prescribe, with few side-effects. The Committee also discussed how empirical diagnosis followed by hormonal treatment was extremely likely to be the most cost-effective strategy; the cheaper hormonal treatments are so cheap that even if the number of women presenting with endometriosis was small (and even if hormonal treatments had no effect on superficially similar conditions like dysmenorrhoea) that the cost of prescribing these drugs to otherwise healthy women was negligible.

It was expected that hormonal treatments are harmful for fertility. In actual fact the NMA suggested that progestogen treatment might improve fertility, but this is thought to be an inconsistency with the evidence underpinning the NMA and not reflective of the actual effects of progestogen treatment on fertility. As a result of this, no analysis has been conducted on the best hormonal treatment for preserving fertility.

However, in women who have both pain and infertility as a symptom of endometriosis, the effectiveness of hormonal treatment at controlling pain coupled with its low cost meant hormonal treatment was preferred at ICERs less than £13,027 / QALY, where it is replaced with surgical treatment with adjunct hormonal therapy.

11.1.3.3.5. Clinical evidence statements

Comparison 1: GnRH agonist versus no treatment

Pain

Very low quality evidence from 1 trial (n=35) found a clinically significant beneficial effect of GnRH agonist treatment (buserelin IN) compared with expectant management for dysmenorrhoea relief (measured using VAS) at 12 weeks after starting treatment.

Comparison 2: GnRH agonist versus placebo

Dysmenorrhoea

Moderate quality evidence from 1 trial (n=88) demonstrated a clinically significant beneficial effect of GnRH agonist treatment (leuprorelin IM depot) compared with placebo in the reduction of dysmenorrhoea (measured using VAS) at 12 weeks after starting treatment.

Pelvic pain

Moderate quality evidence from 1 trial (n=88) demonstrated a clinically significant beneficial effect of GnRH agonist treatment (leuprorelin IM depot) compared with placebo in the reduction of pelvic pain (measured using VAS) at 12 weeks after starting treatment.

Moderate quality evidence from 1 trial (n=46) found a clinically significant beneficial effect of GnRH agonist treatment (triptorelin IM depot) compared with placebo in the cessation of pelvic tenderness at 6 months after starting treatment.

Dyspareunia

Moderate quality evidence from 1 trial (n=88) demonstrated a clinically significant beneficial effect of GnRH agonist treatment (leuprorelin IM depot) compared with placebo in the reduction of deep dyspareunia (measured using VAS) at 12 weeks after starting treatment.

Very low quality evidence from 1 trial (n=46) found a clinically significant difference between GnRH agonist treatment (triptorelin IM depot) and placebo in the cessation of pelvic tenderness at 6 months after starting treatment.

Comparison 3: Combined oral contraceptive pill versus placebo

Pain

Low and moderate quality evidence from 1 trial (n=96) found a clinically significant beneficial effect of treatment with a combined oral contraceptive compared with placebo for dysmenorrhoea (measured using VAS), but no clinically significant difference between treatments for non-menstrual pelvic pain score (measured using VAS) or induration.

Comparison 4: GnRH agonist versus danazol

Pain

Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=59) found no clinically significant difference between GnRH agonist treatment (nafarelin IN) compared with danazol for pelvic tenderness and pelvic induration at 3 months (during treatment period) and at the end of the 6 month treatment period.

Patient requiring surgery because of reappearance of symptoms and positive findings at pelvic examination

Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=62) reported no clinically significant difference between GnRH agonist treatment (buserelin IN) and danazol in the number of patients requiring surgery because of reappearance of symptoms and positive findings at pelvic examination at follow-up at least 12 months after treatment ended.

Quality of life

Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=169) found no statistically significant difference in quality of life (PGWBI and modified Nottingham Health Profile) between GnRH agonist (nafarelin IN) and danazol at the end of the 6 month treatment period. Clinical significance was not calculable as the data reported in the paper were descriptive.

Comparison 5: GnRH agonist versus levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

Quality of life

Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=83) reported no clinically significant difference between GnRH agonist treatment (leuprolide IM) and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in quality of life (PGWBI) at the end of the 6 month treatment period.

Comparison 6: GnRH agonist versus DMPA-SC

Effect on daily activities

High to moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=274) found no clinically significant difference between GnRH agonist treatment (leuprolide IM) and depot MPA (given by SC injection) regarding the mean number of hours of productivity lost at employment and housework at the end of the 6 month treatment period and at 18 months (12 months post-treatment).

Comparison 7: GnRH agonist 1 + placebo versus GnRH agonist 2 + placebo

Pain

Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=192) found no clinical significant differences between GnRH agonist treatments (nafarelin 200mcg twice per day (BDS) IN and IM placebo compared with leuprolide depot 3.75mg IM plus IN placebo) for pelvic tenderness and pelvic induration at 6 months after the end of the treatment period.

Comparison 8: GnRH agonist + placebo versus progestin + placebo

Quality of life

Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=48) reported no clinical significant differences between treatment with a GnRH agonist (nafarelin 200 µg IN BDS) and oral placebo compared with oral medroxyprogesterone (BDS 15 mg) and IN placebo in terms of overall quality of life (measured using Goldberg’s general health and Nottingham Health Profile Questionnaire) at 6 months after the end of the treatment period. Results were poorly reported.

Effect on daily activities

Very low quality evidence from 1 trial (n=48) reported no clinical significant differences between treatment with a GnRH agonist (nafarelin 200 µg IN BDS) and oral placebo compared with oral medroxyprogesterone (BDS 15 mg) and IN placebo in terms of the effects on daily activities (measured using the Coping wheel, Inventory of Social Support and Interaction – ISSI and demands, control and support questionnaires) including sleep disturbances, anxiety-depression, household work, vacation life and leisure, sexual life, motivation, emotional balance and work activities (including psychological work demands, intellectual discretion at work, authority over decisions at work and social support) at 6 months after the end of the treatment period. Results were poorly reported.

Comparison 9: GnRH agonist + placebo versus danazol + placebo

Pain

Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=49) found no clinically significant difference between GnRH agonist treatment (nafarelin 200mcg BDS -400mcg/d- IN) and oral placebo compared with oral danazol (200mg 3 times per day (TDS)) plus IN placebo for pelvic tenderness and pelvic induration at 6 months after the end of the treatment period.

Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=96) found no clinically significant differences between GnRH agonist treatment (nafarelin 200mcg BDS -400mcg/d- IN) and oral placebo compared with danazol (200mg TDS) plus IN placebo for pelvic tenderness and pelvic induration at 12 months after the end of the treatment period.

Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=253) found no clinically significant difference between GnRH agonist treatment (leuprolide 3.75mg monthly IM) and oral placebo compared with oral danazol (800mg once daily) plus IM placebo for pelvic tenderness at 6 months after the end of the treatment period.

Comparison 10: Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate versus cOCP + danazol

Pain

Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=80) found a clinically significant beneficial effect of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment compared with cOCP plus danazol for dysmenorrhoea at 6 months after starting treatment and at the end of the treatment period (at 12 months). Very low- to low-quality evidence from the same study reported no clinically significant difference between the 2 intervention groups for dyspareunia and non-menstrual pelvic pain at 6 months after starting treatment and at the end of the treatment period (at 12 months).

Patient satisfaction

Low quality evidence from the same RCT (n=80) reported no clinically significant difference between depot medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment compared with cOCP plus danazol regarding patient satisfaction with treatment (very satisfied/satisfied) at the end of the treatment period (at 12 months).

Comparison 11: GnRH agonist (triptorelin) + E/P pill versus E/P pill

Pain

One RCT (n=102) reported a clinically significant beneficial effect of GnRH agonist (triptorelin) + E/P pill (gestodene 0.75 mg/ethinylestradiol 0.03 mg) treatment compared with E/P pill (gestodene 0.75 mg/ethinylestradiol 0.03 mg) alone for dysmenorrhoea and nonmenstrual pelvic pain at 8 months during the treatment period and for dysmenorrhoea at the end of the treatment period (at 12 months). Evidence was of low to moderate quality.

Low quality evidence from the same study found no clinically significant beneficial effect of E/P pill (gestodene 0.75 mg/ethinylestradiol 0.03 mg) compared with GnRH agonist (triptorelin) + E/P pill (gestodene 0.75 mg/ethinylestradiol 0.03 mg) treatment for nonmenstrual pelvic pain at the end of treatment period (at 12 months).

Comparison 12: GnRH agonist (goserelin) versus cOCP

Pain

Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (n=57) demonstrated a clinically significant beneficial effect of GnRH agonist (goserelin) treatment compared with cOCP (0.02 mg ethinylestradiol and 0.15 mg desogestrel) for dyspareunia at the end of the treatment period (at 6 months). The same study reported no clinically significant difference between the 2 study arms for nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dysmenorrhoea at the end of the treatment period (at 6 months) and for dyspareunia, non-menstrual pelvic pain and dysmenorrhoea at 6 months after the treatment period. Evidence was of very low to low quality.

11.1.3.4. Evidence to recommendations

11.1.3.4.1. Relative value placed on the outcomes considered

As pain relief is the primary reason for patients seeking treatment, this was the most critical outcome for the NMA, pairwise meta-analysis and pairwise comparison within this review. Health-related quality of life was also critical as this might be considered to give a more broad reflection of patient experience than pain relief alone, but data were only available for the pairwise comparison. Withdrawal due to adverse events and adherence to treatment were also critical outcomes as these reflected specific issues relating to the use of certain treatments and were addressed within the NMA and pairwise meta-analysis.

Rate of success, satisfaction with treatment, effect on daily activities and reduction in size and extent of endometriotic cysts were considered important outcomes as they were less clear indicators of effectiveness and were addressed within the pairwise comparison.

11.1.3.4.2. Consideration of clinical benefits and harms

The evidence from the NMA supported the use of hormonal treatments for pain relief in women with endometriosis and evidence from the pairwise comparison was broadly consistent with this, therefore the Committee used the NMA for most decision-making. The Committee agreed with the evidence and further highlighted that the benefit from hormonal treatments was due to their efficacy in stopping or reducing periods. There was a desire from the Committee to reduce the number of repeated operations for women with endometriosis, further supporting maintenance of pain relief using hormonal treatments wherever possible.

Although they chose not to be specific about recommending a particular hormonal treatment in the recommendations, they stated that the first-line hormonal treatment would generally be the oral combined contraceptive pill or progestogens as they have good efficacy and typically have side effects that women may find more tolerable. The evidence showed that cyclic use of the combined oral contraceptive pill is effective, but the Committee were also aware that continuous and tricycling (where three packets are taken in a row, followed by a pill free interval) use of the pill are used in clinical practice, and although evidence was not available on these regimens in the literature, the Committee have found in their experience that these were also effective with limited adverse events.